ABSTRACT

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rh‐EGF) in healing foot ulcers in diabetic patients.

Methods: A total of 28 subjects with foot ulcers were recruited into the pilot study. Patients who had obvious peripheral arterial disease, trans‐tibial amputation, plastic surgery or skin flap, and skin graft were excluded. The properly debrided wounds and the non closure wounds after toe amputation were included. When the wounds became clean or uninfected, they received twice‐a‐day treatment with 0·005% Easyef and hydrocolloid dressing. The size and severity of the wounds were evaluated. Others such as blood sugar, renal and hepatic function, serum albumin, vascular condition, foot infection or osteomyelitis were assessed.

Results: All of 28 patients had positive response of granulation (100%). Complete healing was noted in 13 out of 23 subjects and finished 8‐week follow‐up (56·5%). The rates of wound closure were 43·3%, 59·9%, 68·7%, and 84·8% in week 2, 4, 6 and 8, respectively, regardless of the severity. Being dropped out, three patients needed further interventions. No skin allergic reaction. Over‐granulation was observed in one female patient (3·7%), but as minor.

Conclusions: Easyef has positive effects on healing of moderate‐to‐severe foot ulcers and demonstrated being safe to diabetic patients. The drug had high tolerability and compliance.

Keywords: Diabetes, Easyef, EGF, Foot ulcer, Wound healing

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic patients hospitalised for the treatment of foot infection/ulcers have been up to nearly 500 cases, in equal to 25–35% of total in‐patients year‐on‐year in Department of Endocrinology, Choray Hospital (1). The treatment so far is empirical including control of blood sugar, management of infection, surgical debridement, wound dressing, off‐loading of pressure. In aspect of wound care, plant‐oil dressing or hydrocolloid dressing has been used for many years in the department. Diabetic foot ulcers are generally difficult to heal and frequently lead to amputation if the wounds become infected or gangrene. Growth factors treatment may be a promising approach to diabetic foot wounds 2, 3. One of the most studied growth factors, epidermal growth factor (EGF), has been available as Easyef in Korea since 2001 and now existing in China and some countries in South America. The results from several small‐sampled studies in some Asian countries revealed EGF to produce various degrees of success 4, 5, 6, 7. In Vietnam, EGF is the first growth factor commercially available in the mid 2007. The trial was thus designed to determine both the effect and the safety in treatment of diabetic foot ulcers.

METHODS

The trial was a pilot study conducted at Department of Endocrinology, Choray Hospital, HoChiMinh City, Vietnam. Sponsored by DaeWoong Pharmaceutical Company, it was designed, conducted, analysed, and had data interpreted independently of the sponsor. The first two authors vouch for the validity and completeness of the reported data. Approval to conduct the trial was obtained from the ethics committee of the hospital, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Eligibility criteria were a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus at 35 years of age or older, an age of < 75 years at the time of study entry and foot ulcer with grade 2 or 3 defined by Wagner‐Meggitte. Exclusion criteria included pregnant or breast‐feeding women, hypersensitivity to topical preparations, chronic diseases [hepatic disorders with ALT, AST or total bilirubin more than 2·5 times normal; chronic kidney disease (creatinin ≥ 1·5 mg/dl), heart failure, active pulmonary tuberculosis; malignant diseases, connective tissue disease, using immunosuppression agents or corticosteroid therapy], acute diseases [unstable angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, hypertension grade III (JNC 7), cerebrovascular accident], malnutrition (albumin < 3 g/l), prominent arterial insufficiency (diagnosed by clinical examination and low‐extremity Duplex scan), foot infection, untreated osteomyelitis, neuroarthopathy (Charcot foot), electrical or radiation trauma.

Upon study, the wound was debrided and dressed with the cotton gauze impregnated with plant oil (‘mu u’ oil). Patients were advised to rest on beds. The wound must have been clean (no necrosis, edema, inflammation or exudation) at the study entry.

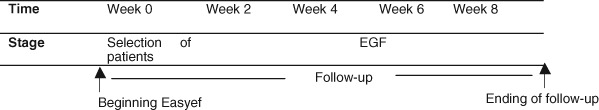

Patients were consecutively recruited into EGF group (Figure 1). The drug was sprayed locally twice and covered with urgotul gauze once daily. Patients and their relatives were instructed to continue the treatment modality after discharge.

Figure 1.

Schematic of treatment.

Study treatment

The highly purified recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rh‐EGF) manufactured by Daewoong Pharmaceutical company (Korea), with brand name Easyef, spray form 0·005% contains 1 ml rh‐EGF and 9 ml solvent containing 20 mg of methyl para‐hydroxybenzoat. It was applied topically over the wound twice a day and covered with the same hydrocolloid dressing, and cotton gauze externally. Patients were seen at week 2 after treatment; then at 4, 6 and 8 weeks thereafter. These patients were also encouraged to attend other, unscheduled visits to improve the monitoring and indicate the appropriate intervention.

Information was collected on peripheral neuropathy, whole blood count, serum transaminases, serum creatinin, serum albumin, lung X ray, foot X ray, low‐extremity Duplex scan, microbiology culture, the therapeutic intervention (such as at‐bed care, surgical debridement, minor amputation) was noted at the time of study entry. The situation of wound, including the size of wound (length, width, depth), infection and proceeding of granulation, was reported through study period by two chief investigators. Pictures of the ulcers were taken by camera CYBUS 5·0. Complete healing was defined as full epithelialisation of the wound with absence of discharge. Any clinical abnormal reactions or undesirable findings appeared during or after the administration of EGF was noted, regardless of the causal relationship with the drug. Moreover, the level of patient compliance was assessed at regular intervals of follow‐up.

The study outcomes were the rate of complete healing, the level of reduction in wound size by time, and the causal relationship of abnormal reactions and Easyef.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted according to the intention‐to‐treat principle. The rate of healing was calculated in percentage of wound completely healed after 8‐week treatment with Easyef. The healing time was the duration of complete closure demonstrated in mean (standard deviation). The rate of wound reduction was presented in percentage compared to the initial size.

RESULTS

Enrollment and baseline characteristics of participants

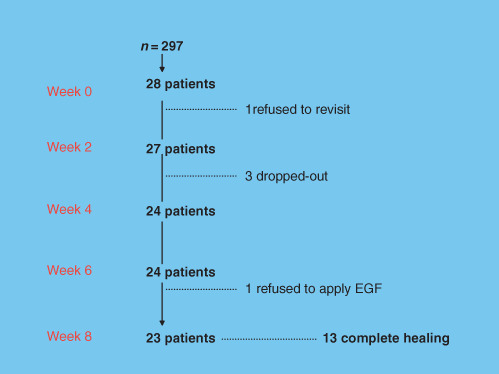

Between September 2007 and June 2008, a total of 297 potentially eligible participants were registered. Of them, 28 subjects (Figure 2 and Table 1) who fulfilled all of criteria were selected. There were 26 patients who finished the follow‐up (92·9%), 1 patient did not visit after the first week and 1 refused to administer Easyef after the sixth week. Out of 26 patients, 3 (10·7%) were dropped out because of either uncontrolled infection or having skin graft consequently.

Figure 2.

Enrollment of the patients and completion of the study. The baseline profile of participants was demonstrated in (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (n = 28)

| Characteristics | Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex: Female/male (n) | 15/13 | Creatinin mg/dl, mean (SD) | 1·15 (0·69) |

| AST u/l, mean (SD) | 27·57 (20·51) | ||

| Age years, mean (SD) | 59·25 (10·81) | ALT u/l, mean (SD) | 26·61 (14·85) |

| Peripheral neuropathy (n, %) | 26 (92·9) | Albumin g/dl, mean (SD) | 3·54 (0·62) |

There were 22 cases of positive microbiology among 28 infected ulcers (78·6%). 18 ulcers of grade 2 (64·3%). 10 ulcers of grade 3 (35·7%), 4 cases of osteomyelitis included. About the wound size, 12 ulcers of 5–15 cm2, 8 of 16–30 cm2, and 8 of > 30cm 2. The majority of cases underwent surgery 20 (71·4%) (Table 2). All cases of osteomyelitis were aggressively resected before beginning with Easyef.

Table 2.

Wound characteristics (n = 28)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Neuropathic cause | 26 (92·9) |

| Infected | 28 (100) |

| Osteomyelitis | 4 (14·3) |

| Grade | |

| 2 | 18 (64·3) |

| 3 | 10 (35·7) |

| Size | |

| 5–15 cm2 | 12 (42·8) |

| 16–30 cm2 | 8 (28·6) |

| > 30 cm2 | 8 (28·6) |

| Intervention | |

| Bed care | 8 (28·6) |

| Surgical debridement | 12 (42·8) |

| Toe amputation | 8 (28·6) |

All 28 patients had been granulated. Of 23 ulcers, 13 (56·5%) achieved complete healing during 8 weeks of follow‐up with the mean healing time of 38·9 days (18–56 days). Ten more ulcers healed consequently.

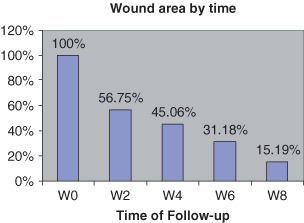

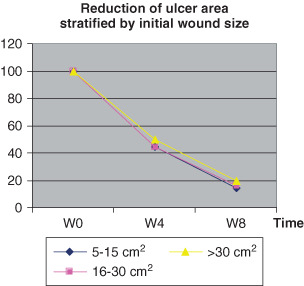

Rate of reduction of wound size by time

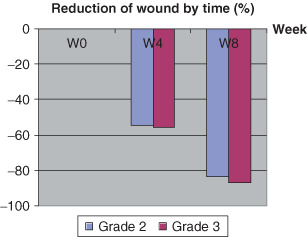

At 4 weeks, wound sizes were < 50% (Figure 3), and only 15% in the eighth week (Table 3). Wound size reduced up to more 80% in the eighth week, regardless of grade or size (Table 4, 4, 5).

Figure 3.

Reduction of wound area by time.

Table 3.

Ulcers healed and wound size by time (n = 28)

| Week | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients followed up | 28 | 27 | 23 | 24 | 23 |

| Complete healing (cumulative numbers) | 0 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 13 |

| Wound size (%), mean (SD) | 100 | 56·75 | 45·06 | 31·18 | 15·19 |

| (28·8) | (37·17) | (33·41) | (24·69) |

Table 4.

Reduction of wound area by initial grade and size

| % of reduction in wound size (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Week 4 | Week 8 | |

| Grade | ||

| 2 | 54·37 (39·22) | 83·27 (29·78) |

| 3 | 55·96 (35·17) | 87·20 (14·76) |

| Size | ||

| 5–15 cm2 | 55·93 (40·19) | 86·12 (26·33) |

| ≤ 30 cm2 | 55·5 (37·23) | 83·68 (25·9) |

| > 30 cm2 | 49·83 (32·92) | 80·43 (17·0) |

Figure 4.

Reduction of wound size stratified by severity of ulcers.

Figure 5.

Reduction of ulcer area stratified by initial wound size.

In the cases of being dropped out, one patient was referred to orthopedist for skin graft (at 3 week) because the wound had large surface area; two others with osteomyelitis had recalcitrant infection.

Abnormal reactions

No adverse reaction or local skin sensitivity was noted. One patient was thought to have a minor over‐granulation (appeared at 7 week). The wound healed in the following days without any intervention. Two patients that refused the follow‐up reported no abnormal effect.

Compliance

Patients receiving study medication had high compliance, 26 of 28 participants (92·9%). 23 patients sprayed EGF as scheduled in 8 weeks. Two remaining patients stopped Easyef for reasons unrelated to drug. Three others used the trial drug until the day of withdrawal.

DISCUSSION

The main conclusion of this study is that 13 of 23 (56·5%) diabetic foot ulcers healed with local application of Easyef 5% for 8 weeks under the management of a diabetes team.

Both in vivo and in vitro data have demonstrated the efficacy of EGFs in enhancing wound healing 8, 9, 10, 11. The previous trials demonstrated that EGF healed diabetic foot ulcers faster than placebo 5, 6, 7 and increase collagen content of the wound (7). The rate of fully healing in 12 weeks (manufactured by Nycomed, Austria) in hEGF 0·04% group, hEGF 0·02% group and placebo group were 95%, 57·1% and 42·1%, respectively (6). The dose‐dependent effect of EGF on the formation of granulation tissue also revealed in randomised‐control studies 10, 12. The dose sensitivity observed in the studies was in accordance with a requirement for the sustained presence of EGF in the promotion of wound repair.

Ulcers in the study were moderately‐to‐severely necrotic. It must be stressed that meticulous wound care such as debridement, callus reduction, bone resection and control of infection also played a vital role in promoting wound healing. Debridement enabled removal of necrotic tissue, maintained drainage, and allowed better surface contact with rh‐EGF. The drug promotes epidermal regeneration and corneal epithelialisation by/in the way of (1) stimulating the production of protein such as fibronectin and increasing the number of fibroblasts in the wound, (2) enhancing the proliferation of epithelial cells and migrating them to fill up the wound (2).

EGFs have good tolerability. Its safety also was demonstrated in experiments on toxicity (9). Few adverse effects of EGF have been reported, as minor and well tolerated in all studies 5, 6, 7, 10.

The benefits from EGF, like other growth factors, will not be achieved if the wounds are not treated properly. When using Easyef, the most important thing is to cautiously select patients and ulcers. The ulcer candidates for Easyef must be non infected at the time of spraying EGF and in arterial sufficiency.

The strength of EGF is the positive effect of rapid granulation and promoting healing more impressively in deep wounds compared to superficial wounds. At specialist clinics in the country, most in‐patients with diabetic foot ulcer are at high risk for amputation because of severe necrosis, osteomyelitis or peripheral arterial disease (13). If Easyef shortens the time of wound healing it will help to reduce the length of stay and the risk of superinfected and amputation consequently. Furthermore, patients can be discharged at the time of on‐going tissue regeneration and continue EGF treatment at home because the drug is very easy to use and has an excellent tolerability profile.

A 61‐year‐old female suffered an ulcer in the left foot 2 weeks before admission. A grade II ulceration was located in the sole with dimension of 6 × 2 cm and tendon exposure. After aggressive treatment of infection and surgical debridement, the wound was applied Easyef and urgotul dressing. Granulation grew up over and tendons were partially covered at week 8. The wound fully healed in 114 days.

The result from studies suggest that EGF may be beneficial in wound healing, however, the actions and benefits of EGF will be defined further. Treatment with EGF may increase the medical expenditure for patients, especially in the situation of a developing country like Vietnam. It has thus far been unwilling to use the drug as an adjunctive treatment of neuropathic diabetic foot wounds. Randomised‐controlled trials are therefore needed to provide consistent evidence for not only the superior efficacy but also the cost‐effectiveness of EGF compared with the conventional technique of wound healing in diabetic individuals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Support by grants and Easyef from Daewoong Pharmaceutical Company, Vietnam. We thank Mr Seo Jong Won and PhMD Khanh Nguyen Yen for their assistance throughout the study.

Dr Hoa reports receiving lecture fee from Daewoong. The financial relationships did not pose a conflict of interest to authors.

APPENDIX

22 patients with chronic neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers took part in a randomised‐control study. In the EGF group, 8 cases achieved complete wound healing while the untreated group only achieved 4 cases of complete healing after 12 week follow‐up. The EGF group demonstrated more rapid, significant wound healing ability than the untreated group (5). Baseline biopsy revealed similar levels of collagen in both the study groups. But the follow‐up samples demonstrated a significantly higher level of collagen in EGF group than placebo group. The number of fibrinoblasts was higher in EGF when compared with placebo group.

A 55‐year‐old female had ulcer with dimension of 5·5 × 3 × 1·8 cm at the first right toe. The toe lost much tissue. She could be indicated for toe amputation, but she refused it. Repeated debridement at bed, and application of Easyef helped to save it.

Nine cases healed from day 67 to 114. Only one case did not heal at 15 weeks (the initial wound size of 104 cm2).

The mean duration of hospitalisation is 16·7 days (SD 11·8), counted from the beginning time of EGF treatment. The overall length of stay in hospital was 27·8 days (SD 10·5). The mean days of antibiotic was 12·0 (12·2) ngày.

Among four cases of osteomyelitis, two patients healed completely, one patient was re‐infected with organism different from other initial microorganism.

This will allow health care providers to control the wound environment to achieve complete and durable wound healing.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hoa LT, Han Chau NH. Patient profile in Department of Endocrinology, ChoRay Hospital, 1996–2000. Fulltext of scientific presentations in The first National Conference on Endocrinology and Diabetes, Hanoi, Oct 2001:419–25.

- 2. Steed DL. Modulating wound healing in diabetes, The diabetic foot, 6th edn. Missouri USA: Mosby, 2001;395–403. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennett SP, Griffiths GD, Schor AM, Leese GP, Schor SL. Growth factors in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcer. British Jour of Surg 2003;90:133–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown GL, Curtsinger L. Stimulating of healing of chronic wounds by epidermal growth factor. Plast Recontr Surg 1991;88:189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim KJY. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rh‐EGF) in the treatment of chronic neuropathic diabetic foot ulcer. Poster 98, 5th International Symposium on the DF; 2007 May 9–12; The Netherlands.

- 6. Tsang MW, Wan Keung RW, Wong WKR, Hung CS, Lai KM, Tang W, Cheung EYN, Kam G, Leung L, Chan CW, Chu CM, Lam EKH. Human epidermal growth factor enhances healing of diabetic foot ulcers. Diab Care 2003;26:1856–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Viswanathan V, Rajesh K, Mary B. Efficacy of recombinant human epidermal growth factor in healing diabetic foot ulcers—preliminary results. Poster 102, 5th International Symposium on the DF; 2007 May 9–12; The Netherlands.

- 8. Nanney LB. Epidermal and dermal effect of epidermal growth factor during wound repair. J Invest Dermatol 1990;94:624–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong WKR, Lam E, Huang RC, Wong RS, Morris C, Hackett J. Applications and efficient large‐scale production of recombinant human epidermal growth factor. Biotechnology and Genetic engineering Reviews 2001;13:51–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hong JP, Dong Jun H, Wha Kim Y. Recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF) to enhance healing for diabetic foot ulcers. Annals of Plastic Surgery 2006;56:394–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee HK. The phase II clinical study of DWP401 (rhEGF) for the evaluation of the efficacy of epidermal growth factor (EGF) on diabetic foot ulcer. Document supplied by Daewoong Pharmaceutical Company, Oct 1998–June 2000.

- 12. Buckley A, David JM, Kamerath CD, Woodward SC. Epidermal growth factor increases granulation tissue formation dose dependently. J Surg Res 1987;43:322–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoa LT, Nguyen TK. Risk factors for lower‐extremity amputation in diabetic ulceration. Fulltext of scientific topics contributing to The 3rd Vietnam National Congress of Diabetes and Endocrinology, Hue, April, 2005: 742–50.