ABSTRACT

Pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence data are increasingly being used as indicators of quality of care and the efficacy of pressure ulcer prevention protocols. In some health care systems, the occurrence of pressure ulcers is also being linked to reimbursement. The wider use of these epidemiological analyses necessitates that all those involved in pressure ulcer care and prevention have a clear understanding of the definitions and implications of prevalence and incidence rates. In addition, an appreciation of the potential difficulties in conducting prevalence and incidence studies and the possible explanations for differences between studies are important. An international group of experts has worked to produce a consensus document that aims to delineate and discuss the important issues involved, and to provide guidance on approaches to conducting and interpreting pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence studies. The group's main findings are summarised in this paper.

Keywords: Pressure ulcer, Prevalence, Incidence, Prevention, Quality of care

INTRODUCTION

Pressure ulcers are burdensome for affected patients and their carers and for health care systems. They cause considerable physical and psychosocial morbidity, increase mortality, and are labour intensive, time‐consuming and costly to treat 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

It has been estimated that in the USA, pressure ulcers affect about 1·7 million people per year and cost approximately US$8·5 billion annually (6). In the UK, about one in 150 of the general population develops a pressure ulcer each year, and estimated annual expenditure on pressure ulcer care represents about 4% of the UK National Health Service budget (5). Similarly, in the Netherlands, about 1% of health care expenditure is on pressure ulcer treatment (4).

In recent decades, our understanding of the factors involved in the development of pressure ulcers has improved (7), and there is widespread acknowledgement that most pressure ulcers are avoidable 8, 9. Consequently, many health care settings have developed and implemented protocols and guidelines that use strategies to prevent pressure damage occurring in patients who are at risk of pressure ulceration (10). In addition, some national organisations and government regulatory bodies have set targets for reducing the number of patients affected by pressure ulcers 11, 12, 13. A further significant development has been the introduction by some health care funding bodies of financial penalty and/or incentive schemes related to pressure ulcer development 14, 15. These schemes may involve government‐directed compulsory implementation of specific measures or protocols to reduce the risk of pressure ulcer development (15).

One means of monitoring the success of prevention protocols and ensuring fair application of financial incentive or penalty schemes is accurate evaluation of rates of pressure ulcer occurrence. Epidemiological studies that examine numbers of existing pressure ulcers (i.e. prevalence studies) and that report rates of development of new pressure ulcers (i.e. incidence studies) are increasingly being used for this purpose and as indicators of quality of care 3, 16, 17, 18. However, difficulties exist in ensuring these studies produce accurate results that allow meaningful tracking of data over time and valid comparisons between health care settings and facilities 16, 18. Indeed, the many studies that have examined pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence to date have produced very varied results (17). Differences in the study population, quality of care, the nature of any prevention protocol in place, and how the studies were conducted are some of the myriad factors that contribute to this variability.

In addition, it is clear that much confusion exists around the definitions and implications of ‘prevalence’ and ‘incidence’, and there is considerable need for educational resources that assist in clarifying understanding.

In response to these challenges, an international group of experts was convened to identify and discuss the issues involved in conducting and interpreting prevalence and incidence studies. The group's ultimate aim was to develop a consensus document that improves knowledge and understanding of prevalence and incidence in the context of pressure ulcers, and that contributes to accurate standardised data collection and valid study interpretation.

Following a meeting in February 2008, the expert working group further developed and refined the meeting's findings. The resulting international consensus document—Pressure Ulcer Prevention: prevalence and incidence in context—was published in January 2009, and is of relevance to all those involved in the field of pressure ulcers, including health care practitioners, health care managers, researchers and policy makers (19).

ISSUES IDENTIFIED

The major issues identified by the expert working group were:

-

•

confusion over the definitions, implications and uses of the terms ‘prevalence’ and ‘incidence’

-

•

difficulties in conducting pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence studies:

-

•

collecting and recording data

-

•

defining the study population

-

•

identifying pressure ulcers

-

•

classifying pressure ulcers

-

•

a need for awareness of the pitfalls of evaluating, interpreting and comparing pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence studies.

This paper summarises the findings published in the consensus document (19).

DEFINITIONS

Prevalence and incidence are epidemiological terms that have specific definitions and implications. However, they are sometimes used incorrectly and interchangeably (16). To add to the confusion, different research settings may use the same types of prevalence or incidence analysis but give them different names. It is therefore essential that reports of prevalence and incidence studies clearly state definitions of the terms used.

Prevalence

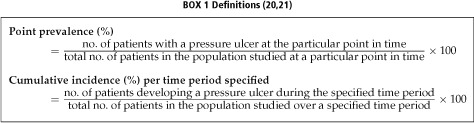

The method used most commonly to indicate prevalence is ‘point prevalence’. Point prevalence indicates the proportion of a defined set of people who have a pressure ulcer at a particular moment in time (20). It may be expressed as a percentage (i.e. per 100 members of the population studied), or per 1000 or 10 000 members of the population studied (Box 1).

Incidence

Incidence provides an estimate of the rate of occurrence of new pressure ulcers over time. It is often measured in a simplified form as ‘cumulative incidence’ (which may also be referred to simply as ‘incidence’ or as ‘incidence estimate’) (21). Cumulative incidence indicates the proportion of the population studied that develops a new pressure ulcer over a specified time period (usually weeks or months, rather than years) (Box 1).

Other definitions

Period prevalence indicates the number of patients who have a pressure ulcer at any time during a specified period (rather than at one particular point in time) (21).

Incidence density indicates the rate of occurrence of pressure ulcers per unit of population time at risk, which may be defined, for example, as rate per 1000 hospital inpatient days or per 100 admissions to a health care facility (22).

Facility‐acquired pressure ulcer rate is used to differentiate pressure ulcers acquired during inpatient treatment from those acquired in the community (22). The rate is usually expressed as the percentage of patients who did not have a pressure ulcer on admission subsequently develop one. Thorough documented admission skin assessments are essential for the accuracy of this approach. When documentation of admission ulcers is reliable, facility‐acquired pressure ulcer rate may provide a reasonable estimate of incidence and of prevention protocol efficacy.

Implications and uses

Valid application of the results of prevalence and incidence studies relies on a clear understanding of the differences between these types of analysis. By estimating the rate of occurrence of new pressure ulcers, incidence analyses are generally considered to provide a clearer indication of the effectiveness of a pressure ulcer prevention protocol than do prevalence analyses 16, 22.

Prevalence indicates the total number of patients affected by pressure ulcers and therefore can be used to show resource requirements and to aid planning and resource allocation (20). Effective prevention protocols would be expected to reduce incidence. Such protocols may also eventually produce a reduction in prevalence, although generally to a lesser extent than the reduction in incidence.

Incidence studies are generally more time‐consuming and therefore more expensive to conduct than prevalence studies. For practical and budgetary reasons, a prevalence study is sometimes chosen in preference to an incidence study even though the results will not provide as clear an indication of prevention protocol efficacy.

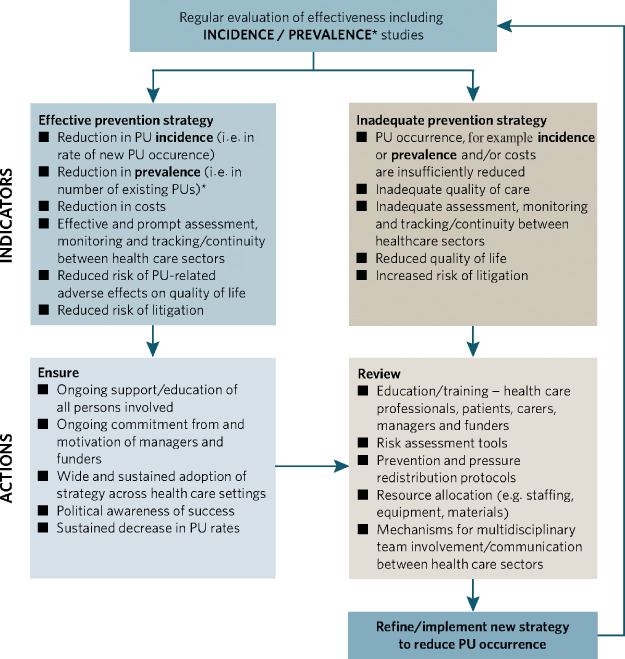

The information collected by epidemiological studies can also be used to prompt detailed examination of factors that contribute to pressure ulcer development, and so may contribute to refinement of prevention protocols (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Role of prevalence and incidence studies in monitoring and developing strategies to reduce pressure ulcer occurrence (19). Reproduced with permission from MEP Ltd.

Prevalence and incidence rates are increasingly being used to assess the efficacy of prevention protocols and quality of care. Although neither rate directly measures the effectiveness of treating existing pressure ulcers, studies that collect data to calculate the rates may also collect data that can be used to indicate treatment efficacy.

DATA COLLECTION AND RECORDING

Accurate, complete, consistent data recording is essential for meaningful prevalence and incidence study results. Data collection and recording will be affected by numerous factors, including the study assessors’ level of training and skill in performing clinical assessments and completing documentation, the type and content of the data recording system, the ease of extraction of data from the recording system, and the length of time over which data are collected.

Retrospective prevalence and incidence studies may produce underestimates because it is known that a significant proportion of pressure ulcers are never documented (3). Conversely , inaccurate diagnosis of other skin lesions as pressure ulcers may lead to overestimates of prevalence and incidence. Prospective studies have the opportunity to devise and use study‐specific data collection systems that reduce the likelihood of missing data elements. Ideally, these incorporate guidance on performing risk assessment and prompt the use of prevention protocols.

DEFINING THE STUDY POPULATION

The nature of the population studied in a prevalence or incidence study will have a fundamental impact on the study's findings. For example, for study populations based on care setting, pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence rates are likely to be higher in a geriatric unit or an intensive care unit than on a maternity unit or across a wide range of care settings (23). This is because risk of pressure ulcer development is likely to vary with the nature of the patients across care settings.

Defining a study population involves specifying the case mix, that is the type of patient included in the study (often defined by care setting) and their risk of pressure ulceration, along with study inclusion or exclusion criteria, for example risk assessment scale scores, comorbidities and level of non participation. Significant differences in the demographic, comorbidity and pressure ulcer risk profiles of study populations can complicate and even invalidate comparisons of study outcomes.

Determining risk

Recognition that experienced clinical evaluation may not identify every patient at risk has lead to the development of many pressure ulcer risk assessment scales 24, 25, 26, 27. These are a potentially useful aid in prevalence and incidence studies for categorising patients by score or into groups such as ‘low’ or ‘high’ risk. However, differences in the cut‐off points used and in the type of scale used complicate comparisons between studies.

Despite their apparent usefulness, some caution is required in the use of risk assessment scales because of the variable validity of those scales that have been assessed and the omission by some scales of well‐recognised risk factors such as poor nutritional status, advanced age and use of medical devices 28, 29. Risk assessment scales do not identify every patient at risk of pressure ulcer development and should not be used to replace experienced clinical evaluation (18).

IDENTIFICATION OF PRESSURE ULCERS

The accuracy of pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence studies is closely related to the correct identification of pressure ulcers. Some organisations have produced definitions 30, 31 and visual guides (e.g. www. puclas.ugent.be) that aid pressure ulcer identification.

Differentiation of pressure ulcers from other wound types, for example moisture lesions [such as incontinence‐associated dermatitis (IAD) and those caused by sweat] and dressing or tape damage, may be particularly difficult 20, 32.

Repeated, regular, thorough skin inspection is the key to detecting pressure damage. Skin inspections should commence on a patient's admission to a health care facility so that any pre‐admission damage is documented. In addition to providing essential information for epidemiological studies, such documentation will be very important for clinical audit purposes and proving which care facility was responsible for the patient's care at the time of pressure ulcer development.

CLASSIFICATION OF PRESSURE ULCERS

Pressure ulcer classification schemes are used to stratify wound severity and so have the potential to add useful detail to prevalence and incidence studies. For example, in a Japanese study, analysis of pressure ulcer severity following introduction of governmental regulation that involved specific preventive measures showed an overall reduction in pressure ulcer severity: the proportion of severe (Stages III and IV) pressure ulcers decreased and the proportion of less severe (Stage I/II) increased (15).

A number of classifications have been produced, with most comprising four or five numbered stages or grades based on extent of tissue damage, sometimes with additional unnumbered categories 30, 31, 33. However, the use of different criteria by different systems (even when they consist of similar numbers of grades or stages) can contribute to difficulties in comparing prevalence and incidence studies. In recognition of the need for an internationally agreed unified system, the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) and the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) are currently working together to produce an integrated definition and classification of pressure ulcers.

Even for an individual classification system, there are problems ensuring accuracy of application and for many there is a lack of evidence supporting their use (34). For some classification systems, inter‐rater reliability has been shown to be reduced in the reporting of less severe pressure ulcers (33). This finding indicates a particular need for practitioner education and training in the recognition of early signs of pressure damage.

There are several other general issues with the use of pressure ulcer classification systems that may have a particular impact on prevalence and incidence studies, for example identification of non blanchable erythema and deep tissue injury, the NPUAP's ‘unstageable’ category and the use of reverse staging.

Non blanchable erythema

The NPUAP and EPUAP systems both use non blanchable erythema as a defining feature of Stage I/Grade 1 pressure ulcers 30, 31. This sign is deemed present and indicative of pressure damage when reddened skin fails to become paler when light pressure is applied. The use of a transparent interface to apply pressure may help to detect blanching (35). When examining patients with darkly pigmented skin some classification systems provide other criteria, for example the affected area may be a different colour, painful and firmer, softer, warmer or cooler than surrounding skin 30, 31.

An unfortunate consequence of the difficulty of identifying and classifying Stage I/Grade 1 pressure ulcers is their omission from some epidemiological studies (17). This may result in underestimation of pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence rates.

Even when Stage I/Grade 1 pressure ulcers are included in studies, however, under‐reporting may occur because of lack of awareness of the early signs of pressure damage. Under‐reporting of pressure ulcers in general may also occur because of guilt or fear of personal or institutional recrimination.

Deep tissue injury

The NPUAP has recently introduced a further pressure ulceration classification category: deep tissue injury (36). This was introduced because the classification of deep tissue injuries without skin loss as NPUAP Stage I or II does not adequately reflect the severity of these injuries (which can progress quickly to full skin thickness ulceration). (NB In the EPUAP classification system, deep tissue injury is classified as Grade 4 (30).)

Furthermore, deep tissue injuries (in common with other forms of pressure damage) may arise before admission to a health care facility and separate categorisation is anticipated to help to ensure that financial penalties are not unfairly applied to the admitting institution.

Reverse staging

Reverse staging is the use of a pressure ulcer classification scheme to monitor healing, for example to reclassify a healing Stage/Grade III pressure ulcer as Stage/Grade II 34, 37. However, this practice is not recommended, and for the purposes of prevalence and incidence studies, a Stage IV/Grade 4 pressure ulcer should always be counted as such until it is completely healed. Specific tools are available for monitoring the healing of pressure ulcers 34, 37, 38.

Classification by aetiology

In addition to classifying pressure ulcers according to severity, incidence (and to a lesser extent prevalence) studies have the opportunity to collect data that can be analysed to show important information about aetiology and risk factors. This information can be used to inform prevention protocols. For example, in children about half of pressure ulcers are device related (39), suggesting a particular need in this patient group for careful monitoring of the interface between the patient and any medical devices.

EVALUATION, INTERPRETATION AND COMPARISON OF STUDIES

Many potential pitfalls await the appropriate evaluation, interpretation and comparison of prevalence and incidence studies because of the wide range of possible approaches. Careful, systematic examination of studies should include determining:

-

•

definitions of the epidemiological terms used

-

•

source of the data

-

•

characteristics of the study population

-

•

care setting

-

•

how pressure ulcer ‘risk’ was determined and defined

-

•

which pressure ulcer classification scheme was used, whether all classes in the scheme were included in the study, and whether any modifications were made the scheme for the purposes of the study

-

•

whether deep tissue injury was included in the classification system used or counted separately

-

•

what prevention protocol was in place during the study

-

•

what conclusions were drawn and whether they are supported by the study's findings

-

•

whether any comparisons made with other studies were valid.

The validity of comparisons of study outcomes will be enhanced where studies have similar study populations and have used analogous methods of data collection, risk assessment and pressure ulcer classification, and have used similar pressure ulcer prevention protocols.

CONCLUSIONS

Pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence studies are becoming evermore important in the global drive to contain health care costs and to reduce preventable disease. These studies have the potential to provide important information for assessing quality of care and the effectiveness of pressure ulcer prevention protocols, and are increasingly being used to determine health care funding and reimbursement.

Until a standardised approach to all aspects of conducting prevalence and incidence studies is adopted, careful consideration is required when planning these studies and interpreting their results. By increasing awareness of the issues involved, it is hoped that this paper and the associated consensus document will make a significant contribution to increased understanding, improved design and proper application of prevalence and incidence studies .

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The consensus document was made possible through the financial support of KCI Europe Holding BV. The views expressed in the document and this article do not necessarily reflect those of KCI.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allman RM, Laprade CA, Noel LB, Walker JM, Moorer CA, Dear MR, Smith CR. Pressure sores among hospitalised patients. Ann Intern Med 1986;105:337–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berlowitz DR, Brandeis GH, Anderson J, Du W, Brand H. Effect of pressure ulcers on the survival of long‐term care residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1997;52:M106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Whittington KT, Briones R. National prevalence and incidence study: 6‐year sequential acute care data. Adv Skin Wound Care 2004;17:490–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Severens JL, Habraken JM, Duivenvoorden S, Frederiks CM. The cost of illness of pressure ulcers in the Netherlands. Adv Skin Wound Care 2002;15:72–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bennett G, Dealey C, Posnett J. The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK. Age and Ageing 2004;33:230–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kuhn BA, Coulter SJ. Balancing the pressure ulcer cost and quality equation. Nurs Econ 1992;10:353–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bansal C, Scott R, Stewart D, Cockerell CJ. Decubitus ulcers: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol 2005;44(): 805–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hibbs P. The economics of pressure ulcer prevention. Decubitus 1988;1:32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Torra i Bou J, Garcí a‐Fernández FP, Pancorbo‐Hidalgo PL, Furtado K. Risk assessment scales for predicting the risk of developing pressure ulcers. In: Romanelli M, Clark M, Cherry G, Colin D, Defloor T, editors. Science and practice of pressure ulcer management. London: Springer‐Verlag, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whitfield MC, Kaltenthaler EC, Akehurst RL, Walters SJ, Paisley S. How effective are prevention strategies in reducing the prevalence of pressure ulcers? J Wound Care 2000;9:261–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) statement on pressure ulcer prevention. URL: www.npuap.org 1992. [accessed on October 2008].

- 12. Department of Health. The Health of the Nation: a consultative document. London: HMSO, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13. US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: understanding and improving health, 2nd edn. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Welton JM. Implications of medicare reimbursement changes related to inpatient nursing care quality. J Nurs Am 2008;38:325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanada H, Miyachi Y, Ohura T, Moriguchi T, Tokunaga K, Shido K, Nakagami G. The Japanese Pressure Ulcer Surveillance Study: a retrospective cohort study to determine prevalence of pressure ulcers in Japan. Wounds 2008;20:176–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fletcher J. How can we improve prevalence and incidence monitoring? J Wound Care 2001;10:311–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kaltenthaler E, Whitfield MD, Walters SJ, Akehurst RL, Paisley S. UK, USA and Canada: how do their pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence data compare? J Wound Care 2001;10:530–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. VanGilder C, MacFarlane GD, Meyer S. Results of nine international pressure ulcer prevalence surveys: 1989 to 2005. Ost Wound Manage 2008;54:40–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. International guidelines. Pressure ulcer prevention: prevalence and incidence in context. A consensus document. London: MEP Ltd, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Defloor T, Schoonhoven L, Fletcher J, Furtado K, Heyman H, Lubbers M, Lyder C, Witherow A. Pressure ulcer classification. Differentiation between pressure ulcers and moisture lesions. EPUAP Rev 2005;6:URL: www.epuap.org/ review6_3/page6.html. [accessed on October 2008]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bonita R, Beaglehole R, Kjellström T. Basic epidemiology 2nd edn. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ayello EA, Frantz R, Cuddigan J, Jordan R. Methods for determining pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence. In: Cuddigan J, Ayello EA, Sussman C,editors. Pressure ulcers in America: Prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future. Reston, VA: NPUAP, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dassen T, Tannen A, Lahmann N. Pressure ulcer, the scale of the problem. In: Romanelli M, Clark M, Cherry G, Colin D, Defloor T,editors Science and practice of pressure ulcer management. London: Springer‐Verlag, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pancorbo‐Hidalgo PL, Garcia‐Fernandez FP, Lopez‐Medina IM, Alvarez‐Nieto C. Risk assessment scales for pressure ulcer prevention: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2006;54:94–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waterlow J. The Waterlow score card. URL: www.judy‐waterlow.co.uk. [accessed on October 2008].

- 26. Bergstrom N, Braden BJ, Laguzza A, Holman V. The Braden scale for predicting pressure sore risk. Nurs Res 1987;36:205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Norton D. Calculating the risk: reflections on the Norton Scale. Decubitus 1989;2:24–31. Erratum in: Decubitus 1989;2:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schoonhoven L, Haalboom JRE, Bousema MT, Bousema MT, Algra A, Grobbee DE, Grypdonck MH, Buskens E for the prePURSE study group. Prospective study of routine use of risk assessment scales for prediction of pressure ulcers. BMJ 2002;325:797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Defloor T, Grypdonck MR. Validation of pressure ulcer risk assessment scales: a critique. J Adv Nurs 2004;48:613–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. NPUAP . Pressure ulcer stages revised by NPUAP. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP, 2007). URL: www.npuap.org/pr2.htm. [accessed on October 2008].

- 31. EPUAP . Pressure ulcer treatment guidelines. European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP), 1998. URL: www.epuap.org/gltreatment.html. [accessed on October 2008].

- 32. Evans J, Stephen‐Haynes J. Identification of superficial pressure ulcers. J Wound Care 2007;16:54–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Healey F. The reliability and utility of pressure sore grading scales. J Tissue Viability 1995;5:111–14. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dealey C, Lindholm C. Pressure ulcer classification. In: Romanelli M, Clark M, Cherry G, Colin D, Defloor T, editors. Science and practice of pressure ulcer management. London: Springer‐Verlag, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vanderwee K, Grypdonck MH, De Bacquer D, Defloor T. The reliability of two observation methods of nonblanchable erythema, Grade 1 pressure ulcer. Appl Nurs Res 2006;19:156–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. NPUAP . NPUAP deep tissue injury consensus, 2005. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP), 2005. URL: www.npuap.org/ DOCS/DTI.doc. [accessed on October 2008].

- 37. NPUAP . The facts about reverse staging in 2000. The NPUAP Position Statement. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP), 2000. URL: www.npuap.org/ archive/positn5.htm. [accessed on October 2008].

- 38. Woodbury MG, Houghton PE, Campbell KE, Keast DH. Pressure ulcer assessment instruments: a critical appraisal. Ost Wound Manage 1999;45:42–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baharestani MM, Ratliff CR. Pressure ulcer in children and neonates: an NPUAP white paper. Adv Skin Wound Care 2007;20:208–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]