Abstract

This case report describes the first successful use of recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rh‐EGF) in radiation‐induced chronic wound of bone and skin which remains to be difficult to treat. Such wound on the chest of a 59‐year‐old female patient is presented lasting 3 years despite flap surgery and conventional treatment. The treatment with rh‐EGF achieved healing within 16 weeks but further study to evaluate its potential for radiation‐induced chronic wounds is warranted.

Keywords: Radiation‐induced ulcer, Recombinant human epidermal growth factor

Introduction

Radiotherapy is a powerful treatment to control tumour perioperatively or as a sole treatment modality. More than 50% of cancer patients rely on some form of radiotherapy. But despite the advances in delivery of radiotherapy, side effects such as skin damages, oral dryness (xerostomia) and radiation‐induced mucositis are often frequent and even become a dose‐limiting effect. The complications occur because of the susceptibility of these cells which divide rapidly like cancer cells. The affected surface epithelia are typically turnover tissues, in which permanent cell loss at the surface is balanced by continuous proliferations of cells. The radiation response in these tissues is based on progressive cell depletion because of radiation‐induced impairment of cell production. This results in impairment of the epithelial barrier, denudation and ulcerations (1).

One serious complication seen by many plastic surgeons is wound‐healing problems of the skin. The long‐term effect after radiotherapy on the skin includes atrophy, fibrosis and microvascular damage which can lead to problematic non healing wound. Any localised trauma, surgery or infection can aggravate the radiated skin decades after radiotherapy and lead to major wounds difficult to manage. Well‐vascularised flaps are often required to resurface the defect but flap margins may still become dehisced when the irradiated field is not sufficiently debrided.

The evolution of wound care through introduction of the concept of moist wound environment has improved the healing in quality and time. But the treatment effect of advanced wound‐dressing materials has been limited because of the complex pathophysiology behind radiation‐induced skin wound.

Recent studies have introduced the concept of radiation‐induced fibroblast dysfunction as one of the important mechanisms 2, 3, 4. Fibroblasts are stimulated to lay down extracellular matrix, including collagen, by growth factors such as platelet‐derived growth factor (PDGF), epithelial growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and transforming growth factor β (TGF‐β). But irradiated fibroblasts show marked impairment of proliferation and migration, reducing the population of fibroblasts in early wound healing 5, 6. Furthermore, the collagen synthesised by these cells is reduced in amount and abnormal in structure 7, 8.

The development of recombinant growth factors has increased the potential and presented new ideas for acute and chronic wound healing. It has been long recognised that growth factors contribute to various pattern of cell activation during wound healing. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) was discovered in mouse salivary glands in 1962 and was the first growth factor to be described (9). It interacts with the EGF receptor on epidermal cells and fibroblasts (10). In regards to inflammation and cancer, it is shown that salivary EGF levels are markedly reduced in patients with oral inflammations or head and neck tumours (11). Furthermore, radiation‐induced oral mucositis appears to be modified by concentration of EGF in the oral environment, and saliva volume and total EGF volume decrease significantly during the first week of radiotherapy and are maintained at reduced level throughout the therapy (12). This finding by Epstein et al. (12) suggests that higher level of EGF in saliva may be associated with less severe mucosal damage because of radiation therapy. According to the authors’ research, this paper may be the first to report the successful use of rh‐EGF to achieve healing of chronic ulcer caused by radiation.

Case report

A 59‐year‐old female with a radiation ulcer of the right chest visited the clinic. The patient had history of mastectomy and radiation therapy 23 years ago because of breast cancer from a different hospital, and the radiation ulceration began 13 years prior to visit. Medical records regarding this procedure could not be obtained. She recalled the wound size initially being about 3 × 3 cm with persistent, non healing, full‐thickness defect of the chest with exposed rib bone. She maintained cancer free but the wound was neglected until the patient underwent debridement and reconstruction using transverse rectus abdomis flap from another hospital 3 years prior to her visit. However, the upper medial margin of the flap dehisced and ended in non healing and painful ulcer that lasted 3 years. Conservative treatment was unsuccessful despite multiple debridement, treatment with advanced wound dressings and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. On initial examination of her first visit, the ulcer was about 3 × 1 cm with fibrotic tissue and exposed rib bone. The edges of ulcer were epithelialised without granulation on the base, and upon local debridement, only minimal bleeding was noted. There was no sign of infection, and it was confirmed by culture study.

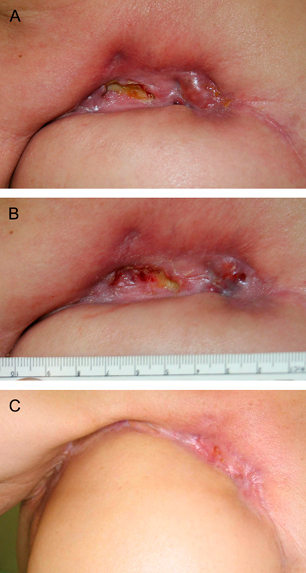

After extensive discussion, the patient gave consent to receive the off‐label use of rh‐EGF because conventional treatment was not successful. The patient was educated to apply the 0·005% rh‐EGF (Easyef®; DaeWoong Pharm., Seoul, Korea) twice a day with silver‐impregnated hydrofiber (aquacell Ag®; Convatec, NJ, USA) and hydrofiber‐foam composite dressing (Versiba®; Convatec). The patient was encouraged to expose and wash the wound gently while taking showers every day. The patient visited the clinic once a week for regular follow‐up. At 2 weeks, partial epithelialisation was noted across the wound and epithelialisation steadily began. By week 12, near‐total epithelialisation of the wound was noted, and at the visit made on week 16, total healing was noted. The patient was free from pain or tenderness and without recurrence at 12 months (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A 59‐year‐old female with a radiation ulcer of the right chest persistent for 3 years which recurred on the margin of the TRAM flap is presented. (A) On initial examination, the ulcer was about 3 × 1 cm with fibrotic tissue and exposed rib bone. (B) The wound at 2 weeks after twice‐a‐day application of recombinant human epidermal growth factor, aquacell and versiva. Note the epithelialisation across the wound. (C) Complete healing is noted at 16 weeks.

Discussion

Non healing radiation ulcers cause serious morbidity, including pain, infection, deformity, psychological stress and reduced quality of life. It remains to be a difficult wound to treat and even may lead to mortality because of overwhelming infections. Despite the optimal standard of care for these wounds including moist dressing, serial debridement, control infection and hyperbaric oxygen therapy, it frequently fails to heal. A well‐vascularised flap is needed to cover these wounds but high complication may rise because of the failure of flap to take to the radiated ulcer bed and thrombosis of the recipient vessels which leads to total or partial flap loss and wound dehiscence (13). As seen in this case, the flap margin was dehisced and failed to heal, re‐exposing the radiated bed.

The histological findings of chronic ulcers after radiation show disturbance in extracellular matrix composition because of interactions between microvascular injury, damaged fibroblasts and altered TGF‐β levels and mast cell activity (14). Despite the fact that microvascular injuries are noted in histology, recent report showed that irradiated tissues are not hypoxic, suggesting that other key mechanisms may be behind the cause for poor wound healing (15). Fibroblasts are stimulated to lay down extracellular matrix, including collagen, by growth factors such as PDGF, epithelial growth factor (EGF), FGF and TGF‐β. But irradiated fibroblasts show marked impairment of proliferation and migration, reducing the population of fibroblasts in early wound healing 5, 6. Furthermore, the collagen synthesised by these cells is reduced in amount and abnormal in structure leading to radiation‐induced fibrosis 7, 8. TGF‐β family also thought to be a major stimulator of radiation‐induced fibrosis by proliferating and stimulating fibroblasts to enhance collagen and extracellular matrix molecule deposition, inhibit collagenase and extracellular matrix degradation and inhibit epithelial cell growth 16, 17.

EGF is produced by platelets, macrophages and monocytes (11). Its primary role is to stimulate epithelial cells to grow across the wound but also acts on fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells (12).

EGF has been reported to significantly accelerate epidermal regeneration of partial‐ and full‐thickness skin wounds in pigs and continuous or prolonged exposure of EGF to increase tensile strength in skin wounds of rats 12, 13. EGF is also known to stimulate epithelialisation in chronic ulcers of diabetic foot (18).

The idea to use EGF on radiated wounds comes from the fact that EGF might stimulate normal fibroblasts rather than abnormal fibroblasts. According to our review, this case may be the first successful treatment using rh‐EGF in radiation‐induced chronic skin ulcer with osteonecrosis. The study by Hetzel et al. showed that the fibroblasts cultured from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis were significantly less stimulated by EGF than normal fibroblasts (19). We have had similar findings where in vitro radiated fibroblasts were significantly less proliferated by rh‐EGF. This may be because of mutation of EGF receptors on the fibroblasts caused by ionising radiation (20). Ionising radiation also leads to increased expression of functionally intact EGF receptors in human keratinocytes and is thought to be a part of stress program in which epidermal cells respond to ensure rapid repopulation of radiated skin (21). Furthermore, EGF is also been reported to inhibit TGF‐β, one of the major factor behind formation of radiation‐induced fibrosis 22, 23. Fragments from multiple reports have supported the rationale for use in cancer‐free radiated wounds, but further research is needed to evaluate the mechanisms behind these phenomena. One of the main concerns of using EGF on radiated wounds may be the possibility to facilitate cancer cell growth. The patient must be informed of the possibilities of cancer recurring despite the fact that the wound is evaluated and confirmed to be cancer free. However, there has been no report of cancer formation using EGF in various wounds since 2002 in Korea. Further research must be performed regarding this issue.

It is important to emphasise that wound healing achieved in radiated ulcers is by a complex mechanism not yet fully understood. This is supported by the fact that various other trials using laser, recombinant PDGF, Pentoxifylline, interferon gamma and topical negative pressure dressing have been reported with some success 14, 24. At this point, the importance of optimal wound care, antibiotic treatment and hyperbaric oxygen must be considered the first line of treatment. Surgical treatment with a well‐vascularised flap is also a dependable solution for larger wounds. However, when conventional methods of treatment fail to cover the radiated wound, it may be necessary to achieve healing through unconventional options. The use of rh‐EGF has been shown to be beneficial, but further clinical evaluation will be needed to verify this approach to consider as an option in refractory cases.

References

- 1. Dorr W, Kummermehr, J . Increased radiation tolerance of mouse tongue epithelium after local conditioning. Int J Radiol Biol 1992;61:369–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferguson PC, Boynton EL, Wunder JS, Hill RP, O’Sullivan B, Sandhu JS, Bell RS. Intradermal injection of autologous dermal fibroblasts improves wound healing in irradiated skin. J Surg Res 1999;85:331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dantzer D, Ferguson PC, Hill RP, Keating A, Kandel RA, Wunder JS, O’’Sullivan B, Sandhu JS, Waddel J, Bell RS. Effect of radiation and cell implementation on wound healing in a rat model. J Surg Oncol 2003;83:185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Withers H. Biologic basis of radiation therapy. In: Perez C, Brady L, editors, Principles and practice of radiation oncology. Philadelphia: Lipponcott, 1992:64–96. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rudolph R, VandeBerg J, Scheider JA, Fisher JC, Poolman WL. Slowed growth of cultured fibroblasts from human radiation wounds. Plast Reconstr Surg 1988;82:669–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang Q, Dickson GR, Abram W, Carr KE. Electron irradiation slows down wound repair in rat skin: a morphological investigation. Br J Dermatol 1994;130:551–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Archer R, Greenwell E, Ware T, Weeks P. Irradiation effect on wound healing in rats. Radiat Res 1970;41:104–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wang Q, Dickson GR, Carr KE. The effect of graft bed irradiation on the healing of rat skin grafts. J Invest Dermatol 1996;106:1053–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cohen S. Isolation of mouse submaxillary gland protein accelerating incisor eruption and eyelid opening in the new born animal. J Biol Chem 1962;237:1555–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nanney LB. Epidermal and dermal effect of epidermal growth factor during wound repair. J Invest Dermatol 1990;94:624–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ino M, Ushiro K, Ino C, Yamashita T, Kumazawa T. Kinetics of epidermal growth factor in saliva. Acta Otolaryngol 1993;500:126–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Epstein JB, Gorsky M, Guglietta A, Le N, Sonis ST. The correlation between epidermal growth factor levels in saliva and the severity of oral mucositis during oropharyngeal radiation therapy. Cancer 2000;89:2258–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gurlek A, Miller MJ, Amin AA, Evans GR, Reece GP, Baldwin BJ, Schusterman MA, Kroll SS. Rob GL. Reconstruction of complex radiation‐induced injuries using free tissue transfer. J Reconstr Microsurg 1998;14:263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dormand E‐L, Banwell PE, Goodacre TEE. Radiotherapy and wound healing. Int Wound J 2005;2:112–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rudolph R, Tripuraneni P, Kozial JA. Normal transcutaneous oxygen pressure in skin after radiation therapy for cancer. Cancer 1994;74:3063–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Denham JW, Hauer‐Jensen M. The radiotherapeutic injury – a complex ‘wound’. Radiother Oncol 2002;63:129–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martin M, Lefaix J, Delanian S. TGF‐beta1 and radiation fibrosis: a master switch and a specific therapeutic target? Int Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;47:277–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hong JP, Jung HD, Kim YW. Recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF) to enhance healing for diabetic foot ulcers. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56:394–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hetzel M, Bachem M, Anders D, Trischler G, Faehling M. Different effects of growth factors on proliferation and matrix production of normal fibrotic human lung fibrosis. Lung 2005;183:225–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chung TD, Broaddus WC. Molecular targeting in radiotherapy: epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Interv 2005;5:15–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peter RU, Beetz A, Ried C, Machel G, Van Beuningen D, Ruzicka T. Increased expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human epidermal keratinocytes after exposure to ionizing radiation. Radit Res 1993;136:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Danielpour D, Kim KY, Winokur TS, Sporn MB. Differential regulation of the expression of transforming growth factor‐betas 1 and 2 by retinoic acid, epidermal growth factor, and dexamethasone in NRK‐49F and A549 cells. J Cell Physiol 1991;148:235–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park JS, Kim JY, Cho JY, Kang JS, Yu YH. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) antagonizes transforming growth factor (TGF)‐beta1‐induced collagen lattice contraction by human skin fibroblasts. Biol Pharm Bull 2000;23:1517–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hymes SR, Strom EA, Fife C. Radiation dermatitis: clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and treatment 2006. Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:28–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]