Abstract

Growing health care costs and changes in health care delivery, such as the adoption of the diagnosis‐related groups, have tremendously affected treatment patterns all over the world. Pathway management is suitable to be responsive to the growing operating requirements and to manage effective and efficient medical care in hospitals. Pathways standardise clinical processes for patients with a similar diagnosis, procedure or symptom thereby optimising the quality of treatment and patient satisfaction. They are utilised by a multidisciplinary team with a primary focus on quality and coordination of care. Considering the key strategies of pathway management, an interprofessional team containing physicians and nurses developed and implemented a clinical pathway for ambulatory treatment of chronic wounds. A precise medical protocol was created to standardise routine procedures, to improve the treatment outcome and to provide an integrated documentation that enhances interprofessional collaboration. We designed a modular concept of four different sheets which provide pre‐defined standards: (a) medical admission, (b) findings and history, (c) topic and systemic treatment and (d) evaluation of outcome criteria. Variances must be merely written down in detail. After 1 year in clinical practice, we state that the use of a clinical pathway for chronic wound management is an effective method of improving clinical processes and patient outcomes.

Keywords: Clinical pathway, Dermatology, Interprofessional care, Quality improvement, Wound care

Introduction

The growing health care costs and the changing health care environment involved are leading to more efficient approaches in delivering medical care. The adoption of diagnosis‐related groups (DRG) in many countries and their frequent use in reimbursement systems was one of the main reasons to implement pathway treatment in hospitals (1). The clinical pathway originally used in the Unites States of America and Australia aimed to shorten the hospital stay and reduce healthcare costs, which has become an increasingly important issue in medicine (2, 3). In the meantime, pathways have been established as a strategy to reduce the persistent evidence of unexplained variation in medical practice (4, 5). In contrast to many kinds of guidelines, initiated by health professions, state or federal agencies or insurers, pathways describe kinds of institution‐based guidelines from the local care perspective. Pathway management that has arisen beside the implementation of DRG in the United States and Australia can often be misunderstood due to confusing nomenclature. In literature, the frequently used term 'critical pathways' can also be called ‘care paths’, ‘clinical pathways’, ‘care maps’, ‘integrated maps’ and ‘anticipated recovery pathways’ (4, 6). Nevertheless, all of these attempt to define local standards based on the best available evidence and increase efficiency by optimising the care delivery process. In contrast to prescribed guidelines, protocols and algorithms, clinical pathways are utilised by a multidisciplinary team and focus on quality and coordination of care.

In principle, pathway management aims at both implementation of institutional guidelines and recommendations developed by societies or authorities into clinical practice, and to harmonise interprofessional care to a local agreed clinical approach in daily routine of medical care.

Because clinical pathways have been established as an appropriate tool to standardise medical care in an inpatient setting, it should be also suitable for application in an ambulatory and day clinic setting, where the patients recur continually. In many places, the clinical management of chronic wounds is merely subject to individual experiences and the local approaches established in the course of time. Furthermore, the chronic nature of complex wounds, the variability in causes and clinical outcomes and the lack of research in wound care interventions make it difficult to prescribe and to evaluate (7, 8). Considering these concerns, in the dermatology's ambulatory wound care centre, an interprofessional team containing physicians and nurses developed and implemented a clinical pathway for the ambulatory treatment of chronic wounds. The key strategies of the pathway concept were primarily to apply a strategy and get a viable tool for quality management and assurance and secondly, to improve the interprofessional collaboration (9, 10).

Pathway implementation

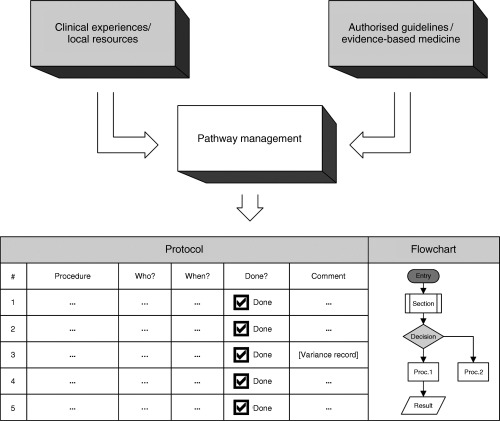

The methodological approach and the aims of implementation pathway management are shown in principle in Figure 1. As a first step, an interprofessional team of senior and junior residents and nurses experienced in wound treatment were recruited. During interval meetings, a modular concept which contains divided care‐sections was created. Authorised guidelines developed by the German Dermatologic Society (http://www.derma.de) concerning chronic venous insufficiency, leg ulcer, compression dressing and quality assurance in phlebology were taken into account as well as existing nursing standards concerning wound therapy. The entire care delivery process, beginning with the admission because of the primary symptom ‘leg ulcer’ and ending with the discharge or intended surgery intervention, was defined by using a flowchart. The sequential and chronological order was stipulated thereby on a mutual basis. This flowchart illustrates a decision tree that discloses the status of the treatment process and suggests the next following step.

Figure 1.

Methodological approach of pathway management.

One of the purposes of the created pathway is to provide a single document which informs all members involved in the clinical workflow, to document all medical and paramedical procedures. Therefore, as a second step, a precise medical protocol was created to standardise routine procedures. This protocol consists of four different sections (sheets), each containing modular steps for which the particular competency and responsibility were defined. The construction of integrated documents should enhance teamwork in the daily routine. The different care‐sections encompass (a) the medical admission, (b) medical findings and history, (c) topic and systemic wound treatment and (d) evaluation of pre‐defined outcome criteria.

After creating a suitable framework for the ambulatory wound pathway, a pilot phase of 3 months was initiated to verify clinical appropriateness and to determine interprofessional manageability. Piloting a pathway in a definite time period helps to identify areas in which the pathway may need to be changed and builds trust among hospital staff (11). During this phase, the modular pathway construction was partially rearranged due to emerging misunderstandings in the course of action and some apparent illogical catenations which solely came to the fore when the pathway was applied in practice. After expiration of the initial pilot phase, the optimised pathway was transformed into daily routine.

Pathway contents

Finally, four prescribed documents and two flowcharts elucidating the order of sections were established throughout the care process. Comprehensive education of hospital staff who should be involved was performed. As shown in Figure 1, protocol sheets were created to present the contents of the particular current or following procedure. The pre‐defined process steps could be ticked off easily. Furthermore, it was necessary to write down when and from whom the section step was fulfilled. Variances and deviations from the pre‐defined pathway which have been required must be written down in detail. This proceeding is absolutely recommended to consider the patients' individualities. The order and the contents of the main sections are shown in Table 1. The sections admission and medical findings and history encompass all essential information for the attending physicians and nurses (Figure 2). The section treatment contains some crucial steps to manage (Figure 3):

Table 1.

Order of essential pathway sections and contents

| Section | Content |

|---|---|

| Admission | |

| Scheduling | Remind previous findings/applied drugs |

| Avoid MRSA‐admission | |

| Admission — nurse | Check enclosed documents |

| Prepare laboratory tests | |

| Admission — physician | Clinical examination and history |

| Coordinate outstanding tests | |

| Preliminary diagnosis | |

| Set individual quality target | |

| Medical history and findings | |

| History | Evaluate medical status |

| Evaluate previous procedures | |

| Evaluate cofactors | |

| Findings | Evaluate vessel‐related and allergic findings |

| Evaluate internal medicine findings | |

| Evaluate consultant findings | |

| Definite diagnosis | |

| Treatment | |

| Documentation | Course of disease |

| Electronic photo documentation | |

| Procedures | Definite local therapy |

| Definite systemic therapy | |

| Advices for home caring | |

| Reporting and scheduling | |

| Evaluation | |

| Main objective | Achievement of objectives |

| Time required | |

| Secondary objectives | Reduction of pain |

| Reduction of itch | |

| Individual | Patient satisfaction |

| Physician's appraisal | |

MRSA, methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus.

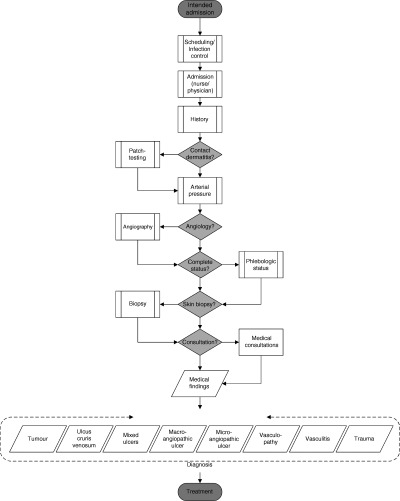

Figure 2.

Flowchart showing essential elements of the sections admission and findings and history.

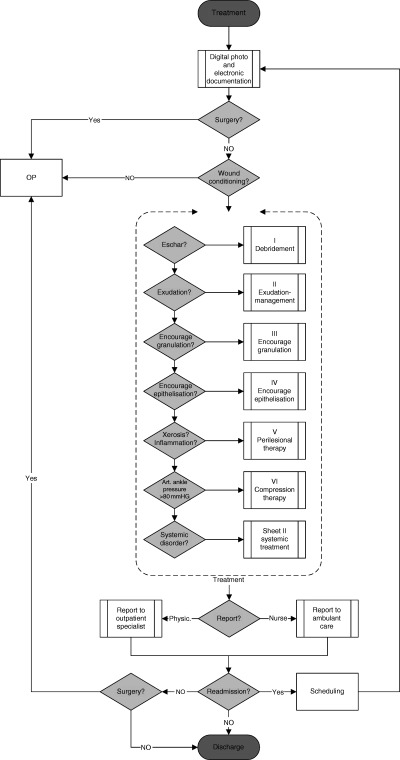

Figure 3.

Flowchart showing essential elements of treatment.

-

•

Debridement

-

•

Exudation

-

•

Granulation

-

•

Epithelisation

-

•

Wound dressings

-

•

Compression therapy

-

•

Systemic therapy

This section has to be recurrently processed at every consultation. Finally, the section evaluation will be filled out at the end of the treatment process to evaluate some pre‐defined outcome criteria.

Pathway in use

The introduced pathway in ambulatory wound care is a dynamic but ‘ready to use’ instrument for daily routine. Quality improvement of the entire care process is based on periodical revision meetings to reflect the defined standards, analysis of variances on the care being delivered at regular intervals and the evaluation of pre‐defined quality indicators such as time to make the definite diagnosis or achieved reduction of parameters like pain or itch. Regular inspections of variance records helped to identify common reasons why the pathway had not been followed. This led to the discussion within the team and regular updating of the pathway when appropriate. The introduced wound pathway was revised several times with the active participation of the involved staff members. The available variance records were taken into account. During the course of time, the local therapy line was adapted to current standards when necessary. During a continuous evaluation process, a component for systemic therapy was added. After 1 year of experience, we state that the use of a clinical pathway for chronic wound management is an effective method of improving clinical procedures, which benefits patient outcomes.

Beneficial aspects

The effectiveness of guidelines predominantly developed by national authorities or medical societies is discussed controversial concerning the introduction into clinical practice. On the one hand, the lack of transparency regarding the development of guidelines is a major obstacle in their appraisal (12). Moreover, guidelines in general are not a very welcome attendant to clinicians because of the assumption that the physician's autonomy is restricted (13). Although these are valid concerns, within a quality improvement context, however, guidelines are a crucial form of process specification and optimisation (14). Hence, pathway management provides a new way to overcome some obstacles which are associated with guideline implementation. In contrast to imposed guidelines, the main benefit of pathway treatment is the conceptual integration of external knowledge and internal experiences. Unfortunately, there is currently little evidence that supports the effectiveness of pathway management, at least at present. But several investigations concerning standardised approaches to the delivery of care may advice to assume that pathway management is beneficial for process delivery and medical outcomes (15, 16). The amount of improvement, however, may vary considerably.

In order for a hospital to become accountable for delivering high quality care, it must be able to deliver three sets of information: evidence of continuous quality improvement, outcome management and clinical practice standards and guidelines (1). Pathway management provides a model which combines these three aspects to one instrument of quality management. This will be achieved by considering the following criteria:

-

•

Available internal knowledge and resources are presented in combination with authorised guidelines

-

•

Responsibilities and roles in the pathway process are clearly constituted

-

•

Provided quality levels will be disclosed by defined wound care standards

-

•

Outcome criteria may be defined individually considering patient's requirements and wound conditions

-

•

Standardisation of the care process is able to reduce variances in treatment patterns and is opposite to intuitive and experience‐guided treatment

-

•

Quality improvement is ensured by periodical reviews within the team

-

•

Workflow construction on a mutual basis contribute to interprofessional collaboration and better acceptance among each other

-

•

Outcome measurement focus on both the individual quality objective and the quality of health care providing

Perspective

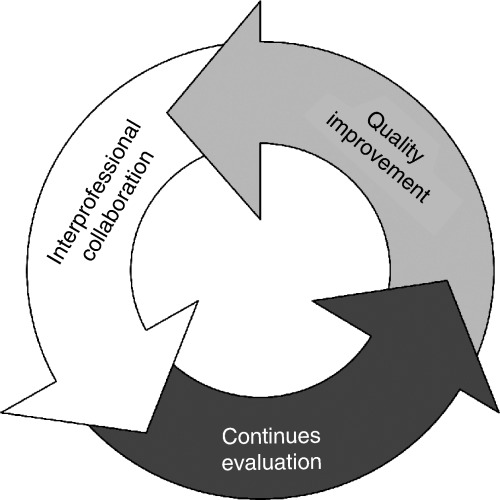

Pathway management is an integrative tool to optimise interprofessional care and quality management in hospitals (Figure 4). It has been shown as a suitable tool to provide standardisation and quality improvement in daily ambulatory wound care. Some beneficial aspects were pointed out, but there is currently no valid and effective method to evaluate entirely the efficiency (17). Particular institutional side‐effects and the impacts on the human resources development are not precisely evaluable, although they serve as additional purposes of the entire concept. It is presumed that combining quality of individual and organisational care objectives with the business objectives would lead to a wider adoption by the medical and paramedical staff involved (18, 19). Further research will be needed to measure and evaluate effectiveness and efficiency of the wound pathway shown here and pathway concepts at all. Equally, cost‐effectiveness studies of wound management is further essential but require the definition of what is an acceptable and consistent outcome for the treatment program (20). The introduced concept of pathway management will make a contribution to determine outcome criteria which consider both the operating efficiency and the individuality of wound care.

Figure 4.

Interlocking benefits of pathway management.

Key Points

-

•

pathway management has been established as a suitable tool to face the growing operating requirements in health care units

-

•

pathway primary focus on standardisation in patient treatment, but they are applicable also in an ambulatory setting

-

•

chronic wound management is difficult to standardise in principle

-

•

a modular concept was developed by an interprofessional team

-

•

external guidelines and internal knowledge and resources were concatenated

-

•

four sections were defined to cover the entire care delivery process

-

–

medical admission

-

–

medical findings and history

-

–

topic and systemic wound treatment

-

–

evaluation of pre‐defined outcome criteria

-

•

a pilot phase of 3 months was initiated to test and verify

-

•

pathway management is performed by using concise protocols and supportive flowcharts which illustrate the care process

-

•

deviations from the pre‐defined pathway are added by way of explanation

-

•

the pathway defines a corridor, however, individual treatment will be ensured

-

•

the treatment steps will be processed recurrently at every consultation

-

•

finally, pre‐defined outcome criteria will be evaluated

-

•

the pathway concept overcomes the obstacles associated with authorised guidelines

-

•

periodical assessment and review ensure quality improvement

-

•

quality improvement focuses on individual and organisational quality standards

-

•

pathway management is an integrative instrument to advance interprofessional care and to manage quality in hospitals

References

- 1. Cheah TS. Clinical pathways – The new paradigm in healthcare? Med J Malaysia 1998;53: 87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pearson SD, Kleefield SF, Soukop JR, Cook EF, Lee TH. Critical pathways intervention to reduce length of hospital stay. Am J Med 2001;110: 175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dy SM, Garg PP, Nyberg D, Dawson PB, Pronovost PJ, Morlock L, Rubin HR, Diener‐West M, Wu AW. Are critical pathways effective for reducing postoperative length of stay? Med Care 2003;41: 637–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pearson SD, Goulart‐Fisher D, Lee TH. Critical pathways as a strategy for improving care: problems and potential. Ann Intern Med 1995;123: 941–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Welch WP, Miller ME, Welch HG, Fisher ES, Wennberg JE. Geographic variation in expenditures for physicians' services in the United States. N Engl J Med 1993;328: 621–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campbell H, Hotchkiss R, Bradshaw N, Porteous M. Integrated care pathways. BMJ 1998;316: 133–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barr JE, Cuzzell J. Wound care clinical pathway: a conceptual model. Ostomy Wound Manage 1996;42: 18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tallon R. Critical paths for wound care. Adv Wound Care 1995;8: 26–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kitchiner DJ, Bundred PE. Clinical pathways. Med J Aust 1999;170: 54–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Atwal A, Caldwell K. Do multidisciplinary integrated care pathways improve interprofessional collaboration? Scand J Caring Sci 2002;16: 360–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yandell B. Critical paths at Alliant Health System. Qual Manag Health Care 1995;3: 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller M, Kearney N. Guidelines for clinical practice: development, dissemination and implementation. Int J Nurs Stud 2004;41: 813–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brook RH. Practice guidelines and practicing medicine. Are they compatible? JAMA 1989; 262: 3027–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berwick DM. The clinical process and the quality process. Qual Manag Health Care 1992;1: 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Luc K. Care pathways: an evaluation of their effectiveness. J Adv Nurs 2000;32: 485–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Walldal E, Anund I, Furaker C. Quality of care and development of critical pathway. J Nurs Manag 2002;10: 115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Darer J, Pronovost P, Bass EB. Use and evaluation of critical pathways in hospitals. Eff Clin Pract 2002;5: 114–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA, Rubin HR. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA 1999;282: 1458–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huttin C. The use of clinical guidelines to improve medical practice: main issues in the United States. Int J Qual Health Care 1997;9: 207–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tallon R. Cost‐effective wound care: new priorities driven by outcomes. Adv Wound Care 1995;8: 48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]