Abstract

Objectives/Hypothesis:

Characterization of the localized adaptive immune response in the airway scar of patients with idiopathic subglottic stenosis (iSGS).

Study Design:

Basic Science

Methods:

Utilizing 36 patients with subglottic stenosis (25 idiopathic subglottic stenosis: iSGS, 10 iatrogenic post-intubation stenosis: iLTS, and 1 Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis: GPA) we applied immunohistochemical and immunologic techniques coupled with RNA sequencing.

Results:

iSGS, iLTS, and GPA demonstrate a significant immune infiltrate in the subglottic scar consisting of adaptive cell subsets (T cells along with dendritic cells). Interrogation of T cell subtypes showed significantly more CD69+ CD103+ CD8+ tissue resident memory T cells (TRM) in the iSGS airway scar than iLTS specimens (iSGS vs. iLTS; 50% vs 28%, P=0.0065). Additionally, subglottic CD8+ clones possessed T-cell receptor (TCR) sequences with known antigen specificity for viral and intracellular pathogens.

Conclusions:

The human subglottis is significantly enriched for CD8+ tissue resident memory T cells in iSGS, which possess TCR sequences proven to recognize viral and intracellular pathogens. These results inform our understanding of iSGS, provide a direction for future discovery, and demonstrate immunologic function in the human proximal airway.

Keywords: iSGS, subglottis, resident memory, clonotype, T cell receptor, TCR sequencing

BACKGROUND

Idiopathic subglottic stenosis (iSGS) is a rare1 but devastating fibroinflammatory airway disease that occurs almost exclusively in adult, Caucasian women2. The disease is characterized by mucosal inflammation and localized fibrosis resulting in life-threatening blockage of the upper airway3. Although the pathology of the associated tissue destruction has been well characterized, the mechanisms responsible for disease initiation and pathogenesis remain unclear. Due to the progressive nature of this disease, surgical interventions aimed at increasing airway diameter are the primary treatment modality.1 Given the significant emotional, physical, and financial costs associated with recurrent airway obstruction4, most research efforts have focused on surgical techniques to improve patency rates5. Highly focused scientific approaches to identify key elements of iSGS disease pathophysiology are critical to the development of novel therapies.

Likely as a consequence of the surgical approach to treatment, understanding of iSGS has historically been based on histopathology. iSGS cases show mucosal fibrosis with a pronounced immune cell infiltrate6. Diverse diseases in divergent organ systems are associated with fibrosis, suggesting common biologic triggers. One of the most well characterized triggers is inflammation7. Anatomically, the subglottis functions as a transition zone from the ciliated lining of the trachea to the squamous epithelium of the larynx. As a consequence, the subglottis has increased exposure to antigen as the cilia-driven upward movement of the airway mucus layer temporarily stalls8.

A central constituent of adaptive immunity to respiratory pathogens, T cells mediate immunosurveillance and protect the host through rapid memory responses upon pathogen re-exposure. Resident memory T cells (TRM cells) have been recently recognized as a distinct population from either central or effector memory T cells (TCM and TEM cells, respectively) given their ability to immediately respond to a localized tissue reinfection and proliferate without the requirement for priming in an adjacent lymph node. Airway TRM cells have been demonstrated to protect against respiratory virus challenge through rapid cytokine production9.

These rapid memory T cell responses are enabled by the antigen specificity of each T cell receptor (TCR). Each T cell has a TCR which can recognize one (or a small number) of the millions of antigens to which humans are continuously exposed. Paired alpha and beta chains in the TCR bind peptide antigen in the context of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on antigen presenting cells (termed peptide-MHC or pMHC). Structurally, this pMHC-TCR interaction occurs predominantly via the TCR beta sequence complementarity determining region 3 (CDR3β)10 (Figure S1). CDR3β sequences are exceedingly diversified, allowing the host to mount specific T cell responses against an enormous array of antigenic peptides (estimates range between 106 and 108 unique CDR3β sequences within the CD8+ T-cell repertoires of young adults11,12). However, new evidence suggests that rather than entirely individualized, there is a surprising degree of TCR repertoire overlap between individuals13. These TCR clones shared between unrelated individuals have been termed “public clonotypes”. Several mechanisms have been proposed to generate public T cell responses, including a structure-based interaction between TCR and pMHC and biases during thymic selection14,15. Although the mechanisms responsible for public T cell responses have yet to be completely established, public clonotypes have been observed in a variety of immune responses, including infectious diseases, malignancy and autoimmunity16.

Given the enigmatic nature of the inciting event in iSGS, we sought to test the hypothesis that a clonal immune response against a conserved antigen was associated with disease. Rather than interrogate protein antigens directly, our unbiased approach applied the principle that an individual’s T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire encodes their antigen exposure history. Harnessing new tools in TCR sequencing coupled with robust curated databases of T-cell receptor sequences with known antigen specificity17–19, we interrogated the target of the observed CDR3β sequences in the mucosal scar of iSGS patients and controls.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Patients.

36 patients with subglottic stenosis were utilized for experiments (25 idiopathic subglottic stenosis: iSGS, 10 Post-intubation stenosis: iLTS, and 1 Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis: GPA) (Table S1). Each diagnosis was confirmed using previously described clinical and serologic criteria20. Subglottic scar was the source of all specimens.

Bulk Tissue RNA sequencing.

Sample Processing:

Surgical biopsies of airway scar from iSGS, and iLTS patients was mechanically digested in bulk, mRNA was extracted with the RNAeasy extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was quantified via nanodrop. RNA was converted to mRNA libraries using the lllumina mRNA TruSeq kit following the manufacturer’s directions. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000. FASTQ files were generated by CASAVA and RNA reads were aligned to the Homo sapiens genome (hg19).

Sequence Processing:

We then utilized a computational approach that accurately resolves relative fractions of diverse cell subsets in gene expression profiles from complex tissues. Cell-type Identification By Estimating Relative Subsets Of RNA Transcripts (CIBERSORT)21, employs linear support vector regression (SVR), a highly robust machine learning approach to deconvolute leukocyte cell types.

Quantitative PCR.

qPCR was performed as previously described22.

Single Cell Suspension from Airway Biopsies.

Suspensions were performed as previously described.23 In brief, surgical biopsies derived from airway scar (Figure S1.) were directly placed into room temperature RPMI media in the operating room, then transferred to the lab for processing within 60 minutes. Tissue was finely minced and incubated in collagenase II plus DNase for 60 minutes. Samples were then passed through a 70micron cell strainer prior to experiments.

Flow Cytometry.

Surgical specimens of airway scars were digested prior to surface staining for CD3, CD45, CD4, CD8, CD69, CD103 (Biolegend Inc, San Diego, Ca.). Lymphocytes were gated by FSC/SSC, doublets were gated out, followed by exclusion of dead cells, and then cells were analyzed for surface protein expression. Representative flow cytometry scheme illustrated in supplemental figure S2. All flow cytometry experiments were acquired with an LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Analysis was performed using FlowJo, LLC software (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR). A minimum of 200,000 events was acquired for each sample.

Mass Cytometry.

CyTOF is a variation of flow cytometry in which antibodies are labeled with heavy metal ion tags rather than fluorochromes. Readout is by time-of-flight mass spectrometry. This allows for the combination of many more antibody specificities in a single sample, without significant spillover between channels28. Single cell suspensions were prepared as described above. Cells were stained with an established panel of metal-conjugated antibodies.24 Samples were then aerosolized and streamed single-file into argon plasma where they were atomized and ionized. The resulting ion cloud was passed through a quadrupole to exclude low mass ions and enrich for reporter ions whose abundance is proportional to cellular features. These reporter ions are quantified by time of flight mass spectrometry and recorded in an IMD format file. These data are parsed into single cell events and converted to a flow cytometry standard (FCS) file for analysis25. CyTOF data was analyzed using the nonlinear dimensionality reduction algorithm viSNE. viSNE is a visualization tool for high-dimensional single-cell data is based on the t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) algorithm that provides a visual representation of the single-cell data that is similar to a biaxial plot, with the positions of cells reflecting their proximity in high-dimensional space. Color is utilized as a third dimension to interactively visualize features of these cells. viSNE accomplishes this visualization without down sampling the data (preventing information loss)26.

Bulk T cell TCR sequencing.

Live, singlet, CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T-cells were sorted with a FACSARIA flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) directly into RLT buffer. Genomic DNA was extracted using a DNeasy Minikit (Qiagen) and high-throughput TCR sequencing was performed using the ImmunoSEQ assay (Adaptive Biotechnologies Corp.)11,13,27. Data were analyzed using the ImmunoSEQ Analyzer (graphical workflow illustrated in supplemental figure S3).

Data Visualization and Statistical Analysis.

Data was visualized in Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was set at P value less than 0.05. Differences between x and y groups were determined using the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests for normal and non-normal distributions, respectively. All statistical analyses were performed with Prism version 8.0.

RESULTS

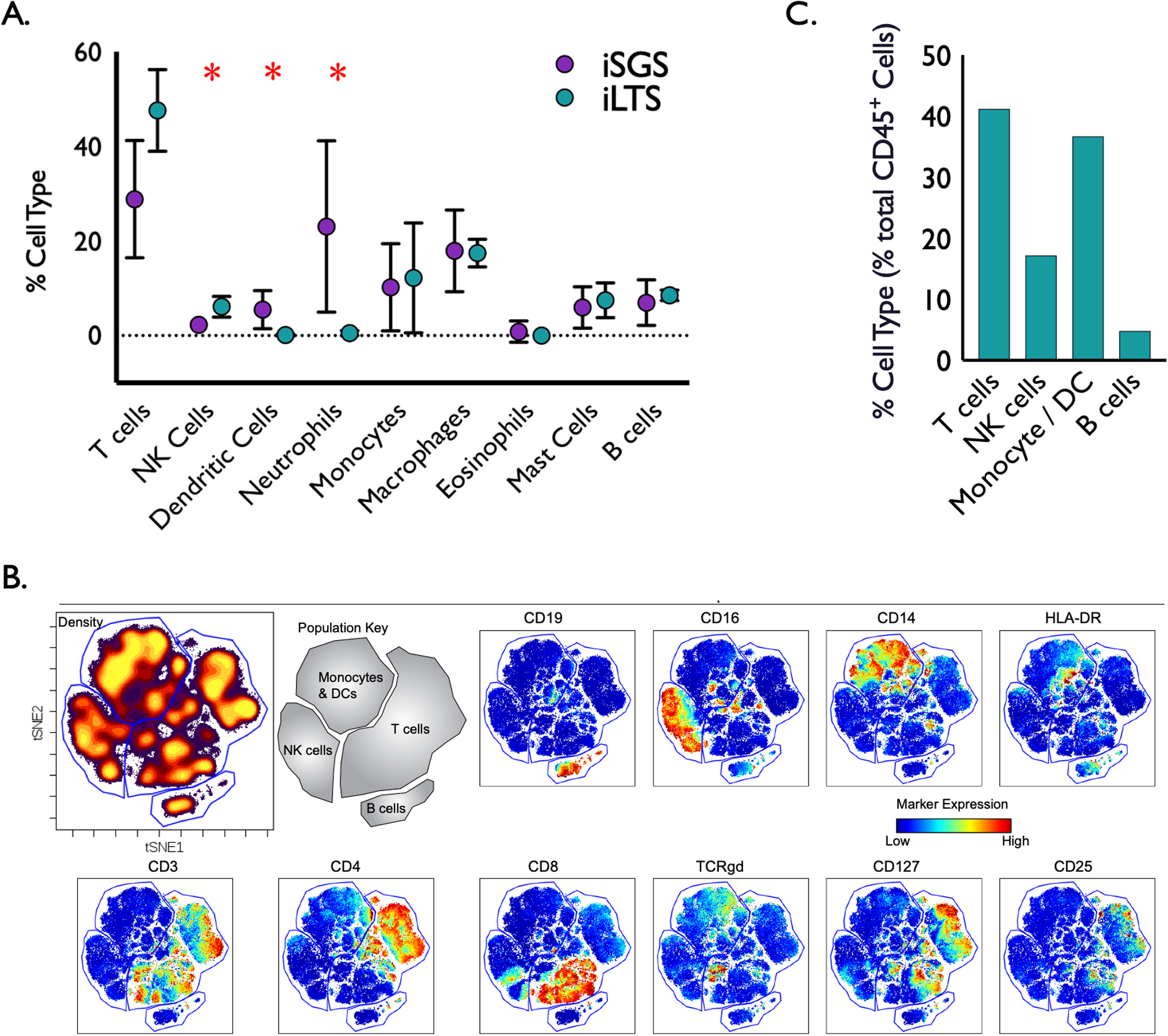

We first investigated the composition of immune infiltrate within the airway scar of iSGS and iLTS patients using the CIBERSORT21 to infer the relative fractions of different immune cell types. The immune compositions varied across samples. While there was inter-subject variability in both groups, significant differences in immune cellular composition between 7 iSGS and 3 iLTS samples were detected (Figure 1A). iLTS subjects had significantly more Natural Killer cells (iLTS vs iSGS: 6.3% vs 2.1% P=0.005), while iSGS samples possessed a significantly higher fraction of neutrophils (iSGS vs iLTS: 22% vs 0.7%; P=0.003) and dendritic cells (iSGS vs iLTS: 5.4% vs 0.3%; P=0.002). Both iSGS and iLTS showed very low percentages of eosinophils, but abundant mast cells, monocytes, and macrophages. Both diseases also had a small but detectable fractions of B cells. These sequencing results were confirmed with a distinct but complementary experiment. Mass cytometry (CyTOF) interrogated immune cell subsets in a single cell suspension derived from the subglottic scar of an iatrogenic post-intubation stenosis (iLTS) patient. CyTOF data was analyzed using viSNE to provide a visual representation of the single-cell data (with the positions of cells reflecting their proximity in high-dimensional space). Color is utilized as a third dimension to interactively visualize features of these cells. Cells that cluster near each other thus share similar expression profiles (Figure 1B). The percent of immune cells (reported as proportion of all CD45+ cells) support the CIBERSORT data. In the subglottic scar of a single iLTS patient, 41% of immune cells were T cells (vs 47 +/− 8.6% seen in the CIBERSORT of LTS samples), 17.2% NK cells (vs 6.1 +/− 2.1%), Monocyte/DC comprised 36.7%, (vs 29% seen when combining the monocyte, macrophage, and DC groups in the CIBERSORT), and B cells 4.8% (vs 8.5 +/− 1.15%) (Figure 1C). The results, confirmed with discrete experimental approaches, demonstrate that several immunologic components of adaptive immunity (namely T cells and antigen presenting dendritic cells) are present in both iSGS and iLTS, albeit with significant differences between the clinical entities.

Figure. 1.

Composition of immune cell infiltrate in iSGS (n=7) and iLTS (n=3) subglottic scars via CIBERSORT deconvolution algorithm applied to bulk tissue subjected to RNA sequencing. iLTS subjects had significantly more Natural Killer cells (iLTS vs iSGS: 6.3% vs 2.1% P=0.005), while iSGS samples possessed a significantly higher fraction of dendritic cells (iSGS vs iLTS: 5.4% vs 0.3%; P=0.002) and neutrophils than iLTS samples (iSGS vs iLTS: 22% vs 0.7%; P=0.003) (A). Confirmatory immune 34-marker mass cytometry (CyTOF) panel was performed on a single cell suspension derived from the subglottic scar of an iatrogenic post-intubation stenosis (iLTS) patient. viSNE analysis was performed on live, intact, CD45+ cells using the 34-marker panel, excluding CD45. Gates were drawn around four broad immune populations (Monocytes/Dendritic cells, T cells, B cells, and NK cells) using expression of measured markers and cell density. Red indicates high expression of a given marker; whereas, blue indicates low expression (B). Percent of immune population reported as proportion of all CD45+ cells for the single patient sample. CyTOF results support CIBERSORT data, demonstrating 41% of Immune cells were T cells, 17.2% NK cells, Monocyte /DC comprised 36.7%, and B cells 4.8% (C).

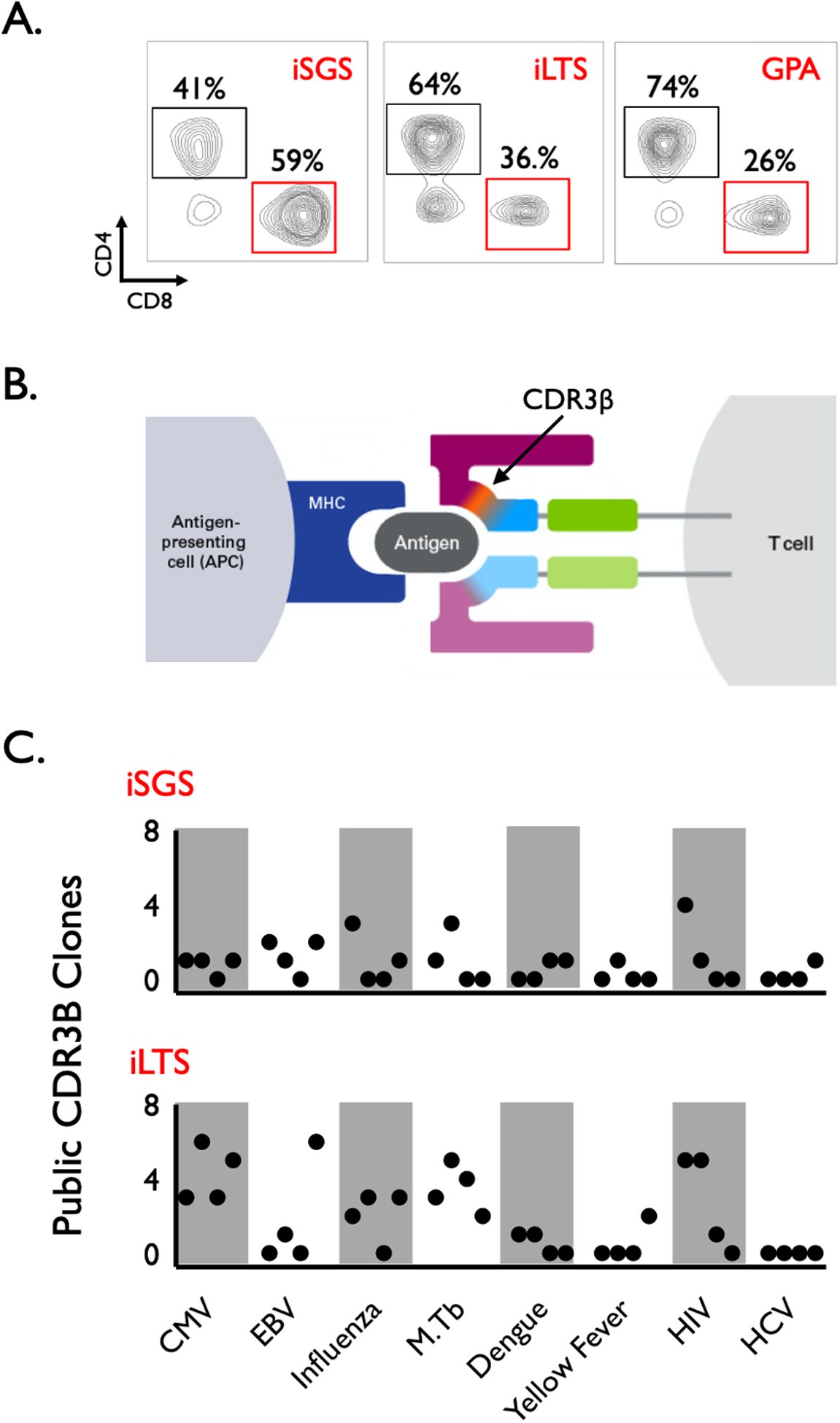

Given results demonstrating both T cells and abundant antigen-presenting dendritic cells in iSGS samples, we sought to more fully characterize the identity of the T cell response in iSGS and iLTS. When comparing single cell suspensions of airway scar between 25 iSGS, 10 iLTS, and 1 GPA patient, all samples had abundant infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Figure 2A). We observed evidence of a predominant CD8+ response in iSGS (iSGS vs iLTS: 36% vs 31% of CD3+ T cells: P=0.37), and a more CD4+ biased response in iLTS (iLTS vs iSGS: 64% vs. 55% of CD3+ T cells; P=0.08), though these differences were non-significant. The single GPA patient had a larger infiltrating CD4+ T cell component.

Figure 2.

Representative flow cytometry of single cell suspensions derived from the subglottic scar of iSGS (n=25), iLTS (n=10), and GPA (n=1) patients. Results showed abundant infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in all samples. Differences in CD4+ and CD8+ (percentages of CD3+ live cells) were non-significant (iSGS vs iLTS CD8: 36% vs 31%: P=0.37), (iLTS vs iSGS CD4: 64% vs. 55%; P=0.08) (A). T cell receptor (TCR) binds peptide in the context of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on antigen presenting cells. Structurally, this antigen-MHC-TCR interaction occurs predominantly via the TCR beta sequence complementarity determining region 3 (CDR3β) (B). The CDR3β region of the TCR was sequenced for bulk sorted CD8+ T cells from iSGS and iLTS airway scar. The CDR3β TCR sequences of CD8+ T cells from iSGS and iLTS airway scar were mapped to curated databases containing TCR sequences of know antigen specificity. In both iSGS and iLTS, there were TCRs homologous to published TCR sequences specific for viral and intracellular pathogens. There were no detectable differences in antigen specificity between iSGS and iLTS subjects (C).

FACS sorted bulk CD8+ T cell fractions from 4 iSGS and 4 iLTS airway scars were then utilized for high-throughput TCR sequencing using the ImmunoSEQ assay® (which sequences the TCR beta chain CDR3 region, Figure 2B). We then compared the sequence identity of the TCRs obtained with the ImmunoSEQ assay® to curated databases of T-cell receptor sequences with known antigen specificity17–19 (in order to assess potential targets of the T cell response in iSGS and iLTS airway scars). There were abundant TCR sequence reads for each subject (average +/− SD of individual CD8 TCR reads: iSGS 699 +/− 400; iLTS 1784 +/− 2700), (average +/− SD of individual CD4 TCR reads: iSGS 1304 +/− 302; iLTS 5309 +/− 8500). The majority of each sample had TCR reads that did not map to TCRs contained in the curated databases. However, in both iSGS and iLTS there were CD8+ TCR clones detected that matched T-cell receptor sequences with known antigen specificity. These included published TCRs recognizing cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein Barr virus (EBV), Influenza, Mycobacterium Tuberculosis (M.Tb), Dengue virus, Yellow Fever virus, Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Figure 2C). There were no detectable differences in specificity to published antigens between iSGS and iLTS subjects. These results reveal subglottic CD8+ T cells in iSGS and iLTS patients possess TCRs homologous to published TCR sequences of know antigen specificity for viral and intracellular pathogens. Additionally, despite the number of public clonotypes observed in each subject, all individuals had a significant number of clonotypes of unknown antigen specificity.

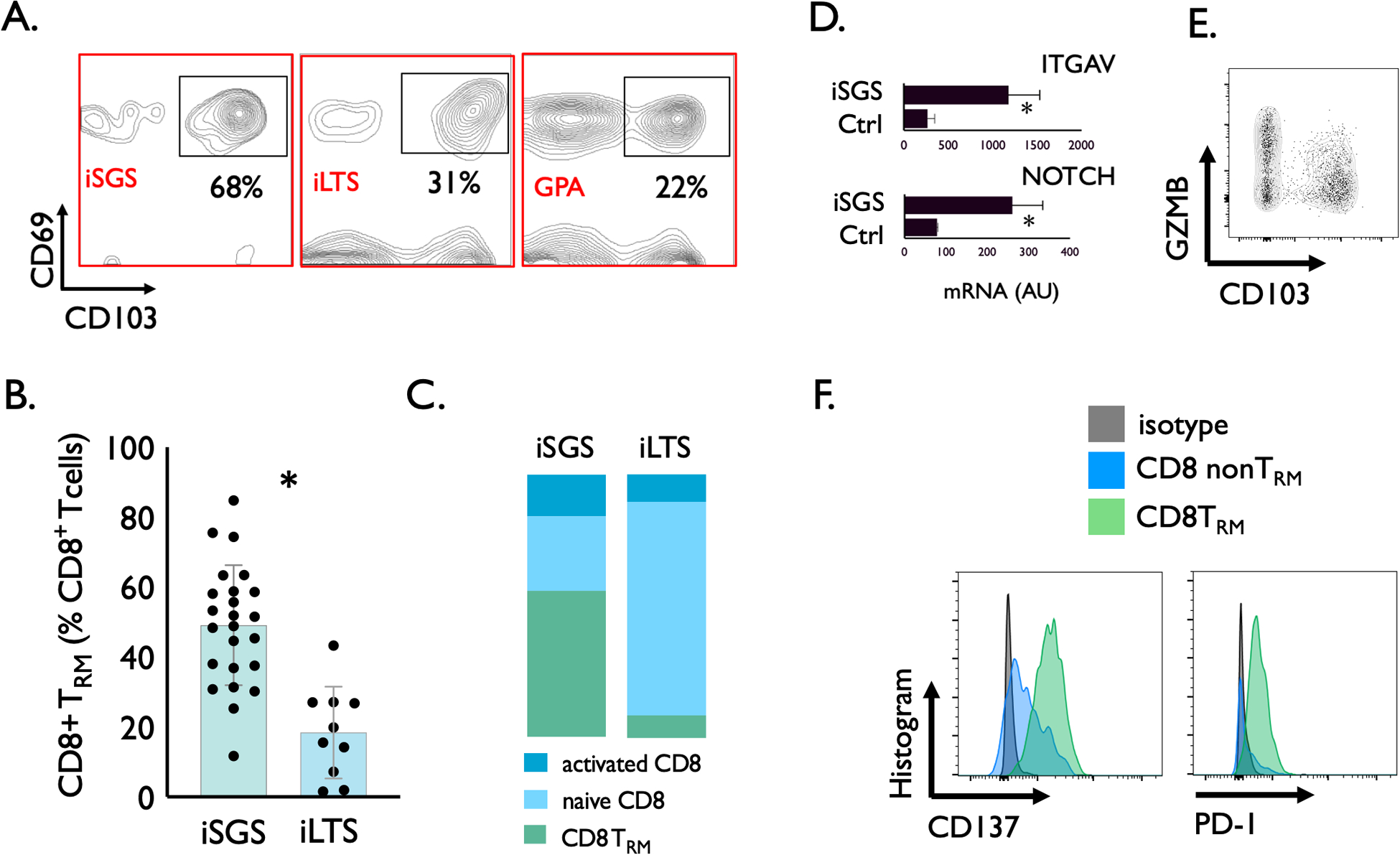

Given the subglottic CD8+ T cells (with TCRs specific for viral pathogens) were obtained during surgical biopsy when subjects had no clinical evidence of active viral infection, we sought to specifically interrogate airway scar for resident memory CD8+ T cells (CD8+CD69+CD103+ T cells: TRM). Single cell suspensions from subglottic scar in iSGS, iLTS, and GPA patients were analyzed by flow cytometry for the frequency of CD8+CD69+CD103+ TRM (Figure 3A). iSGS airway scar had significantly more CD8+ TRM than iLTS (TRM % of total CD8+: iSGS vs. iLTS; 49.1% vs 18.8%, p<0.001, Figure 3B). The single GPA patient had CD8 TRM levels comparable to iLTS patients (21.7%). iSGS and iLTS had significant differences in CD8+ T cell subsets (utilizing CD69 and CD103 surface marker expression to classify cells as follows: naive CD8, CD69−CD103−; activated CD8, CD69+CD103−; and CD8 resident memory, CD69+CD103+). iLTS had significantly more naive CD8 (iSGS vs iLTS: 25% vs 73%, p<0.001). The proportion of activated CD8 (iSGS vs iLTS: 14.2% vs 19.4%, p=0.4) was equivalent between diseases (Figure 3C). iSGS had a higher percentage of CD8 TRM levels (Figure 3B and shown again for comparison in figure 3C). Similarly, iLTS had a higher percentage of naive CD4 (iSGS vs iLTS: 37% vs 84%, p<0.001) while iSGS possessed a greater fraction of activated CD4 (iSGS vs iLTS: 41.7% vs 8.7%, p<0.001). CD4 TRM were low in both disease states and not significantly different (iSGS vs iLTS: 7.3% vs 4.0%, p<0.001) (Figure S4). Analysis of the infiltrating CD4 and CD8+ T cells subsets in iSGS and iLTS scar show significant differences with elevated levels of CD8+ TRM in iSGS airway scar when compared to iLTS patients.

Figure 3.

Representative flow cytometry identifying CD8+CD69+CD103+ (Resident Memory T cells, CD8+ TRM). Single cell suspensions derived from the subglottic scar of iSGS, iLTS, and GPA patients with gating on live cells, singlets, and CD3+CD8+ cells (A). Individual TRM counts in subglottic scar showing iSGS with significantly more CD8+ TRM than iLTS (iSGS vs. iLTS; 50% vs 28%, P=0.0065) (B). Classification of CD8+ T cells by CD69 and CD103 surface marker expression (naive CD8+: CD69−CD103−, activated CD8+: CD69+CD103−, and CD8− resident memory: CD69+CD103+) demonstrate iLTS with higher percentage of naive CD8 (iSGS vs iLTS: 25% vs 73%, p<0.001). The proportion of activated CD8+ (iSGS vs iLTS: 14.2% vs 19.4%, p=0.4) was equivalent between diseases (C). iSGS had a higher percentage of CD8+ TRM levels (Figure 3B and shown again for comparison in figure 3C). QPCR demonstrating significant upregulation in TRM maintenance factors: TGFβ (assayed via downstream TGFβ signal ITGAV) and NOTCH in iSGS scar (ITGAV: iSGS vs Ctrl: 1150 vs. 240 AU, P=0.02. NOTCH: iSGS vs Ctrl: 260 vs. 85 AU, P=0.001) (D). Unstimulated CD8+ TRM derived from single cell suspensions of iSGS subglottic scar were stained for intracellular granzyme B protein (GZMB) as a marker of cytotoxic function (E). Surface protein expression in CD8+ TRM in iSGS airway scar confirm prior antigen exposure (CD137) and TCR activation (PD-1) (F).

We then sought to understand potential molecular mechanisms for CD8 TRM maintenance within the local microenvironment of iSGS airway scar. Local tissue levels of both TGFβ29 and NOTCH30 have been shown to support the migration and maintenance of CD8 TRM. We interrogated levels of these pathways via qPCR to explore factors that might contribute to the observed TRM elevation in iSGS airway scar. Both downstream TGFβ signal (ITGAV, iSGS vs Ctrl: 1150 vs. 240 AU, P=0.02) and NOTCH (iSGS vs Ctrl: 260 vs. 85 AU, P=0.001) were significantly elevated in iSGS airway scar when compared to healthy control airway (Figure 3D). These results show known TRM maintenance pathways TGFβ and NOTCH are elevated in iSGS airway scar and may explain observed elevation in CD8 TRM.

In order to more precisely characterize the phenotype and function of the infiltrating CD8 TRM in iSGS airway scar, unstimulated CD3+CD8+CD103+ TRM derived from single cell suspensions of iSGS subglottic scar were stained for intracellular granzyme B protein (GZMB). Even unstimulated, CD8 TRM possessed abundant intracellular GZMB (Figure 3E). Surface flow cytometry also confirmed prior antigen exposure (via marker CD137) and TCR activation (via marker PD-1) in CD8 TRM in iSGS airway scar (Figure 3F). Within the subglottic scar of iSGS, PD-1 expression was absent on CD8 non-TRM.

DISUCSSION

Idiopathic subglottic stenosis (iSGS) is a rare1 fibrosing disease of the upper airway that effects adult, Caucasian women nearly exclusively2. Histology consistently finds acute and chronic inflammation within surgical biopsies of iSGS airway scar. This study sought to add our understanding of the pathophysiology of iSGS via precise characterization this localized immune response. Our results demonstrate that the human subglottis is significantly enriched for CD8 TRM specialized for immunologic memory in iSGS. These cells have cytolytic function, have previously encountered antigen, and possess TCR sequences proven to recognize viral and intracellular pathogens.

Considerable advances have been made in recent years in understanding the generation and function of memory T cells. Memory T cells are typically parsed into discrete subsets based on phenotypic definitions that connote distinct roles in immunity. In addition to previously identified central memory T cells (TCM), and effector memory T cells (TEM), tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM)—have been increasingly studied over the last 5 years. Unlike TCM and TEM that circulate within blood, TRM cells seed nonlymphoid epithelial barrier tissues during the effector phase of the immune response. They then become permanently established in situ31, forming a unique memory population32 that serves as the first line of defense against local pathogens33. Pre-existing TRM cell populations are long-lived, and not displaced after subsequent infections, which allows multiple TRM cell specificities to be stably maintained within the tissue34. Convergent investigations of human airway immunology have implicated a critical role for these TRM in pathogen clearance within the lung35. Our data now extend a role for these cells to the subglottic airway. The identification of TRM in iSGS also integrates with clinical data on treatment efficacy. The most durable treatment responses in iSGS (albeit with real phonatory impact) have been achieved with surgical removal of the affected mucosa via cricotracheal resection (CTR). Conceivably, CTR would also extirpate all TRM from their local niche in the subglottis.

Given the established roles for CD8+ TRM in host defense against pathogens at mucosal barriers36, the finding of TCR sequences with known specificity against viral and intracellular antigens is unsurprising. The human airway experiences continuous and direct exposure to environmental and microbial antigens – both innocuous and pathogenic – through inhalation and oropharyngeal aspiration. With current technology, financial constraints limited the number of samples available for TCR sequencing. Yet the results of the small number of samples interrogated in this work is consistent with published data showing evidence of a Mycobacterium species within iSGS scar5. Although biopsies of iSGS airway scar do not clinically suggest active infection, Mycobacterium can induce inappropriate host responses to self-antigens leading to autoimmune inflammation37. Poncet’s disease is an inflammatory polyarthritis occurring in TB patients in the absence of culturable mycobacteria in the joint spaces38. In the eye, TB can cause uveitis without mycobacteria39. When taken together, these phenomena suggest that Mycobacterium can induce inappropriate host responses to self-antigens, causing autoimmune inflammation.

Infection can also lead to an autoimmunity when peptides from viral or microbial proteins share sufficient structural similarity with self-peptides and activate autoreactive T cells, termed “molecular mimicry”40. Alternatively, pathogen superantigens can activate T cells that express particular Vβ gene segments, and a subpopulation of these activated cells can be specific for a self-antigen41. Inflammation resulting from viral or bacterial infection can also activate local antigen-presenting cells and enhance processing and presentation of self-antigens, referred to as “epitope spreading”42. The local inflammatory environment may also promote the expansion of previously activated T cells (“bystander activation”)43.

This work is not without limitations. iSGS almost exclusively affects women of fertile or perimenopausal age. Our T-cell results in themselves do not explain this striking gender preponderance. However, our immune characterization does offer a new lens to interrogate the role of estrogen in localized fibroinflammatory scar formation in iSGS. Additionally, the increased abundance of CD8+ TRM in the subglottis of iSGS patients may be a product of altered airway anatomy rather than an essential element of disease pathology. While our data demonstrate the subglottis of iSGS contains more CD8 TRM than comparators groups, the question of the immune composition of the remainder of the “healthy” mucosa in iSGS remains an open question and area for future research. Additionally, while the subglottis in iSGS is enriched in CD8+ T cells with TCRs known to recognize viral and intracellular epitopes, the antigenic target of the most highly represented clones remains unresolved. Future work with single cell RNA sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, in vitro systems44 and phage display libraries45 may be able to identify the antigen targets of these orphan T cell receptors. Additionally, given the rarity of disease and the absence of an effective animal model, investigations in iSGS primarily rely on direct interrogation of human tissue. This allows association of CD8 TRM with iSGS rather than establishes their causality. However, taken together, the results clearly demonstrate iSGS airway scar has a unique elevation in CD8+ TRM when compared to alternate airway pathologies. These cells with cytolytic function, have previously encountered antigen and possess TCR sequences proven to recognize viral and intracellular pathogens. Continued work will be necessary to define the antigenic target of these TCR clones and test efficacy of therapies designed to abrogate their function.

In this work we harness new tools in immunophenotyping and TCR repertoire analysis. The applicability of this approach within Otolaryngology is broad. These data provide the first single-cell suspension methods for the proximal airway; opening a future avenue for an upper airway cellular atlas constructed with single cell technologies. Additionally, mucosal immunology is a fundamental component of disease pathophysiology in many of the diseases encountered in clinical practice (i.e. middle ear mucosa in cholesteatoma, sinus epithelia in chronic rhinosinusitis, and human papilloma virus in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma). More precise characterization of the involved adaptive immune response, as well as the antigenic target of their TCRs may allow for novel, patient-specific immune-based therapeutics.

Conclusions

The human subglottis is significantly enriched in CD8+ TRM specialized for immunologic memory in iSGS. These cells are cytotoxic, have previously encountered antigen, and possess TCR sequences proven to recognize viral and intracellular pathogens. These results inform our understanding of iSGS, provide a direction for future discovery, and demonstrate immunologic function in the human proximal airway.

Supplementary Material

Table. S1. Patient characteristics of specimens utilized for experiments.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: WJM is an employee and shareholder of 10x Genomics, Inc.

All authors take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This manuscript is a Triological Society Thesis (2020-8) and an Original Report. It has not been previously presented or published.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maldonado F, Loiselle A, Depew ZS et al. Idiopathic subglottic stenosis: an evolving therapeutic algorithm. Laryngoscope 2014; 124:498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelbard A, Francis DO, Sandulache VC, Simmons JC, Donovan DT, Ongkasuwan J. Causes and consequences of adult laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope 2015; 125:1137–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelbard A, Donovan DT, Ongkasuwan J et al. Disease homogeneity and treatment heterogeneity in idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 2016; 126:1390–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gnagi SH, Howard BE, Anderson C, Lott DG. Idiopathic Subglottic and Tracheal Stenosis: A Survey of the Patient Experience. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2015; 124:734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniero JJ, Ekbom DC, Gelbard A, Akst LM, Hillel AT. Inaugural Symposium on Advanced Surgical Techniques in Adult Airway Reconstruction: Proceedings of the North American Airway Collaborative (NoAAC). JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017; 143:609–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mark EJ, Meng F, Kradin RL, Mathisen DJ, Matsubara O. Idiopathic tracheal stenosis: a clinicopathologic study of 63 cases and comparison of the pathology with chondromalacia. The American journal of surgical pathology 2008; 32:1138–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR. Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat Med 2012; 18:1028–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SY, Yeh TH, Lou PJ, Tan CT, Su MC, Montgomery WW. Mucociliary transport pathway on laryngotracheal tract and stented glottis in guinea pigs. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2000; 109:210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jozwik A, Habibi MS, Paras A et al. RSV-specific airway resident memory CD8+ T cells and differential disease severity after experimental human infection. Nat Commun 2015; 6:10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borg NA, Ely LK, Beddoe T et al. The CDR3 regions of an immunodominant T cell receptor dictate the ‘energetic landscape’ of peptide-MHC recognition. Nat Immunol 2005; 6:171–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robins HS, Campregher PV, Srivastava SK et al. Comprehensive assessment of T-cell receptor beta-chain diversity in alphabeta T cells. Blood 2009; 114:4099–4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi Q, Liu Y, Cheng Y et al. Diversity and clonal selection in the human T-cell repertoire. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:13139–13144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robins HS, Srivastava SK, Campregher PV et al. Overlap and effective size of the human CD8+ T cell receptor repertoire. Sci Transl Med 2010; 2:47ra64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner SJ, Doherty PC, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J. Structural determinants of T-cell receptor bias in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2006; 6:883–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gras S, Kjer-Nielsen L, Burrows SR, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J. T-cell receptor bias and immunity. Curr Opin Immunol 2008; 20:119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miles JJ, Douek DC, Price DA. Bias in the alphabeta T-cell repertoire: implications for disease pathogenesis and vaccination. Immunol Cell Biol 2011; 89:375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shugay M, Bagaev DV, Zvyagin IV et al. VDJdb: a curated database of T-cell receptor sequences with known antigen specificity. Nucleic Acids Res 2018; 46:D419–D427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tickotsky N, Sagiv T, Prilusky J, Shifrut E, Friedman N. McPAS-TCR: a manually curated catalogue of pathology-associated T cell receptor sequences. Bioinformatics 2017; 33:2924–2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang W, Wang L, Liu K et al. PIRD: Pan immune repertoire database. Bioinformatics 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nouraei SA, Sandhu GS. Outcome of a multimodality approach to the management of idiopathic subglottic stenosis. Laryngoscope 2013; 123:2474–2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods 2015; 12:453–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelbard A, Katsantonis NG, Mizuta M et al. Idiopathic subglottic stenosis is associated with activation of the inflammatory IL-17A/IL-23 axis. Laryngoscope 2016; 126:E356–E361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leelatian N, Doxie DB, Greenplate AR et al. Single cell analysis of human tissues and solid tumors with mass cytometry. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2017; 92:68–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leelatian N, Doxie DB, Greenplate AR et al. Single Cell Analysis of Human Tissues and Solid Tumors with Mass Cytometry. Cytometry B Clin Cytom 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diggins KE, Ferrell PB Jr., Irish JM. Methods for discovery and characterization of cell subsets in high dimensional mass cytometry data. Methods 2015; 82:55–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amir el AD, Davis KL, Tadmor MD et al. viSNE enables visualization of high dimensional single-cell data and reveals phenotypic heterogeneity of leukemia. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31:545–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson CS, Emerson RO, Sherwood AM et al. Using synthetic templates to design an unbiased multiplex PCR assay. Nat Commun 2013; 4:2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bendall SC, Nolan GP, Roederer M, Chattopadhyay PK. A deep profiler’s guide to cytometry. Trends Immunol 2012; 33:323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang N, Bevan MJ. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling controls the formation and maintenance of gut-resident memory T cells by regulating migration and retention. Immunity 2013; 39:687–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hombrink P, Helbig C, Backer RA et al. Programs for the persistence, vigilance and control of human CD8(+) lung-resident memory T cells. Nat Immunol 2016; 17:1467–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofmann M, Pircher H. E-cadherin promotes accumulation of a unique memory CD8 T-cell population in murine salivary glands. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:16741–16746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackay LK, Rahimpour A, Ma JZ et al. The developmental pathway for CD103(+)CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells of skin. Nat Immunol 2013; 14:1294–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cauley LS, Lefrancois L. Guarding the perimeter: protection of the mucosa by tissue-resident memory T cells. Mucosal Immunol 2013; 6:14–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park SL, Zaid A, Hor J et al. Local proliferation maintains a stable pool of tissue-resident memory T cells after antiviral recall responses. Nat Immunol 2018; 19:183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thome JJ, Yudanin N, Ohmura Y et al. Spatial map of human T cell compartmentalization and maintenance over decades of life. Cell 2014; 159:814–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooper AM. IL-17 and anti-bacterial immunity: protection versus tissue damage. Eur J Immunol 2009; 39:649–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haftel HM, Chang Y, Hinderer R, Hanash SM, Holoshitz J. Induction of the autoantigen proliferating cell nuclear antigen in T lymphocytes by a mycobacterial antigen. J Clin Invest 1994; 94:1365–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valleala H, Tuuminen T, Repo H, Eklund KK, Leirisalo-Repo M. A case of Poncet disease diagnosed with interferon-gamma-release assays. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2009; 5:643–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanghvi C, Bell C, Woodhead M, Hardy C, Jones N. Presumed tuberculous uveitis: diagnosis, management, and outcome. Eye (Lond) 2011; 25:475–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bachmaier K, Neu N, de la Maza LM, Pal S, Hessel A, Penninger JM. Chlamydia infections and heart disease linked through antigenic mimicry. Science 1999; 283:1335–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalwadi H, Wei B, Kronenberg M, Sutton CL, Braun J. The Crohn’s disease-associated bacterial protein I2 is a novel enteric t cell superantigen. Immunity 2001; 15:149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller SD, Vanderlugt CL, Begolka WS et al. Persistent infection with Theiler’s virus leads to CNS autoimmunity via epitope spreading. Nat Med 1997; 3:1133–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murali-Krishna K, Altman JD, Suresh M et al. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity 1998; 8:177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simons BC, Vancompernolle SE, Smith RM et al. Despite biased TRBV gene usage against a dominant HLA B57-restricted epitope, TCR diversity can provide recognition of circulating epitope variants. J Immunol 2008; 181:5137–5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deutscher S Phage Display to Detect and Identify Autoantibodies in Disease. N Engl J Med 2019; 381:89–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table. S1. Patient characteristics of specimens utilized for experiments.