Abstract

A 16‐year‐old girl with pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)‐like skin lesions on the extremities, trunk and face developed Takayasu's arteritis (TA; pulseless disease). After 3 years under maintenance cyclosporin A therapy, the patient developed an ischaemic cerebral accident. Severe obstruction of both subclavian and left carotid arteries was found by Doppler sonography, angiography and computerised axial tomography. Evolution of this disease showed some characteristic findings: (a) PG‐like lesions as the first cutaneous manifestation of pulseless disease; (b) methotrexate and cyclosporin A giving good results for the cutaneous lesions, but apparently not exerting an influence on the evolution of TA and the fatal outcome. This morphologic pattern may reflect underlying TA or Wegener's arteritis, and should be termed segmental ulcerative vasculitis.

Keywords: Segmental ulcerative vasculitis, Takayasu's arteritis

Introduction

In 1968, Perry and associates (1) coined the term malignant pyoderma (MP) to describe three patients with a necrotising, aggressive disorder which they considered an ulcerative variant of pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) of unknown origin (2). The authors defined the illness as ‘an idiopathic process consisting of necrotising ulcers affecting the upper trunk, neck and face with progressive and potentially lethal outcome’. Two of the three patients died with this rare, chronic, destructive ulcerating skin disease of unknown cause that affects young adults, usually males. The ulcers with it tend to be distributed mainly about the head and neck region. Some patients have neurological disturbances (1, 3, 4). The distinction of this disease from PG was based on clinical morphology and response to treatment (5). It differs from PG by location of the lesions of the face, neck and upper trunk (1, 2), absence of the undetermined borders and erythema around the ulcers (6) and association with injury of central nervous system of some patients (1, 3, 4).

However, the term MP is not ideal because it does not provide the precise clinical information, has misleading connotations (6), and is a misnomer (7). The concept of MP has created controversy since its origin (5). An increased association of PG with cardiovascular disease, especially pulseless disease (Takayasu's arteritis, TA), has been observed mainly in Japan 8, 9, 10, 11), but there are also reports for other countries 12, 13, 14, 15, 16). In 1997, Gibson et al. (5) provided follow‐up data from these three original cases of Perry et al. (1), as well as additional clinical and laboratory data from subsequently reported cases (17). They concluded that the first three and other patients reported as MP represent cutaneous manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis (WG) and that the term MP assume a place in medical history akin to defunct the term of ‘lethal midline granuloma’ and it no longer be employed as a final clinical diagnosis. In 1997, Perry (18) reviewed his previous cases of MP and decided that it seems best classified as WG. Although new cases, after this revision of concept for MP, have been reported 19, 20, 21), we concur with Gibson et al. and Perry et al. that MP should be abandoned. However, the concept of these ulcers reflects underlying Wegener's arteritis or TA, both being types of segmental ulcerative vasculitis (SUV). Accordingly, we refer now to this entity as SUV. Both may have other features, including granuloma formation or lots of neutrophils.

We describe a case of 16‐year‐old girl with SUV on the extremities, trunk and face, who developed obliteration of both subclavian and the left carotid arteries in the evolution of the disease. This girl is noteworthy for impressive clinical ulcerations, their unusual spreading, resistance of the treatment and lethal evolution.

Case Report

A 16‐year‐old Caucasian girl was seen in 1993 for pain in back and chest, multiple pustules on the extremities and an ulcer of oral mucous after incision for ‘tonsil abscess’. She had a 3‐year history of febrile episodes of unknown origin. Broad‐spectrum antibiotic therapy had not resulted in improvement.

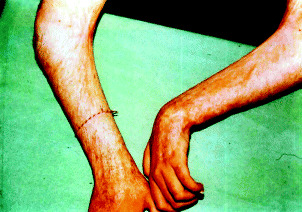

On physical examination, numerous pustules and large necrotic ulcers with undermined borders and inflamed periphery were present on the extremities (Figure 1). A single ulceration was noticeable on the right side of the soft palate (Figure 2). The pathergy phenomenon was found at the sites of injections and scarification tests. The skin lesions have centripetal spreading from extremities to trunk (with a dermatome‐like location) (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Numerous pustules and large superficial ulcers with crusts and inflamed borders on the right hand and cubital joint (possible pathergy phenomenon after venous injections).

Figure 2.

Ulcer on the right side of the soft palate (possible pathergy phenomenon after incision).

Figure 3.

Multiple symmetrical large superficial ulcers with crusts and inflamed borders on both legs and in dermatomal distribution on abdominal skin.

Laboratory investigations revealed an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (160 mm/hour Westergreen), leucocytosis (29·4 g/l), anaemia (haemoglobin 72 g/l; red blood cells 3·3 T/l), increased serum immunoglobulin G (raised 1 and 2 globulins on serum protein electrophoresis), altered cell‐mediated immunity (low levels of CD4, CD8 and natural killer cells) and low levels of serum microelements (iron 6·0 mol/l and zinc 8·6 mol/l). Leucocyte enzymes and nitro‐blue tetrasolium tests were normal. Liver and renal function tests were normal. A skin biopsy specimen revealed a subcorneal pustule with peripheral spongiosis in epidermis, moderate perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells in dermis (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence was negative as was testing for anti‐ANA, anti‐DNA, anti‐Sm and anti‐RNP antibodies. Immunoelectrophoresis of serum and urine did not reveal the presence of paraproteins. The bone marrow studies showed no signs of associated haematological disease. Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) tissue typing demonstrated HLA‐A1, HLA‐A32, HLA‐B5, HLA‐B35 and HLA‐CW4 positively. Normal female karyotype was found. Cultures from a pustule, blood and urine specimens were repeatedly negative. Serology for human T‐cell lymphotropic virus‐1, Epstein – Barr virus, cytomegalovirus and human immunodeficiency virus was negative. Our diagnosis was SUV, based on the clinical and histological data and by exclusion of other diseases.

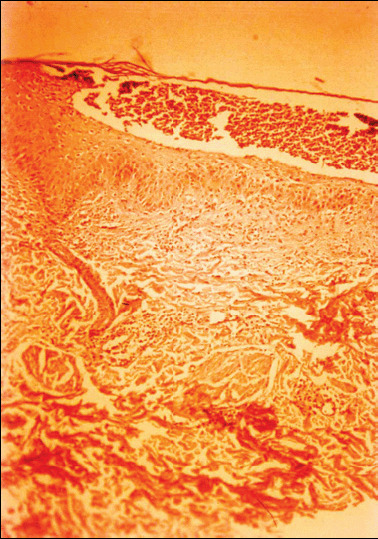

Figure 4.

Epidermal subcorneal pustule with peripheral spongiosis and moderate perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells in dermis. Haematoxylin – eosin, original magnificent ×100.

The patient was initially treated with broad‐spectrum antibiotics, methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg daily), dapsone (150 mg daily), clofazamine (300 mg daily), etretinate (1 mg/kg daily) and thalidomide (300 mg daily) without effect. Pulse therapy with methylprednisolone (1 g daily for 5 days) resulted in a partial resolution of the skin lesions, but new pustules appeared on the thighs, trunk and face (Figure 5) under the maintenance corticosteroid treatment. After initiation of methotrexate (30 mg weekly i.m.), most of the ulcers healed with cribriform scars and anetoderma (Figure 6). Flexural contractures remained at the cubital joints. After 8 months of methotrexate therapy (20 mg weekly), the drug was replaced by cyclosporin A (10 mg/kg daily). The appearance of new pustules was completely stopped. Maintenance cyclosporin A treatment was controlled and a whole‐blood level was between 200 ng/ml and 300 ng/ml. However, any trial for reduction of cyclosporin A dosage <5 mg/kg daily resulted in a relapse of the skin lesions. Hypertrichosis, gingival hyperplasia and depression of this therapy have been observed. Takayasu's arteritis was suspected by inconstant complaints of ear noises, eye scotoms and chest pain, but ophthalmologic examination showed no ocular vascular abnormalities. Three years after the onset of skin lesions and while under maintenance cyclosporin A therapy, the patient developed an ischaemic cerebral incident with hemiparesis of the right part of the body and extremities. Movement and speaking alterations as result of a stroke slowly resolved after intensive treatment in neurology clinic. Physical examination revealed no pulses in both upper extremities. It was not possible to measure the blood pressure. Doppler sonography, angiography (Figure 7), computerised tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the great vessels found severe obstruction of both subclavian and left carotid arteries. After 2 years of cyclosporin treatment, renal biopsy specimens showed interstitial glomerulonephritis. Despite combined maintenance cyclosporin A and corticosteroid therapy, the patient went into a coma and died at the age of 19 years.

Figure 5.

Pyoderma‐like lesions on the face, neck and upper trunk.

Figure 6.

Cribriform scars and anetoderma at the under arms and flexural contractures in axillae and cubital joints.

Figure 7.

Severe obstruction of both subclavian and left carotid arteries and formation of small vessels of aortic arch syndrome documented by angiography.

Discussion

The patient had multiple features suggestive of SUV rather than PG: onset with subcorneal pustules; centripetal spreading of the skin lesions; progressive involvement of upper trunk, neck and face; resistance to several therapeutic approaches, association with ischaemic cerebral incident and a fatal outcome. She completely fulfilled the criteria of the former term MP, now renamed more suitably as SUV. Three years after the onset of SUV, while under maintenance cyclosporin A therapy, she developed an occlusive arterial syndrome of the main branches of the aorta.

The first case of pulseless disease in a young woman has been credited to Savory (22) in 1856. Takayasu (23) in 1908 describes its ocular findings of central vessel anastomoses and reactivated interest in this disease, which as a result is now known as TA. This condition has number of synonyms: occlusive thromboaortopathy, aortic arch syndrome, middle aorta syndrome, atipic coartation of aorta, aortite syndrome, arteritis segmentalis, young orientate female arteritis, etc. In our patient, we do not find changes in the retinal vessels, but Doppler sonography, angiography, computerised tomography and magnetic resonance imaging confirmed occlusive arterial syndrome of aortic arch. It is one of the segmental non specific obliterative panarteritis of the main branches of the aorta with unknown aetiology that affects mainly young women. The association of pulseless disease and cutaneous ulcerations labelled PG was first reported in Japan by Yoshida et al. (8) in 1966. Cutaneous manifestations of patients with pulseless disease have been estimated between 2·8% and 28% of cases, depending on race (13, 24). They include ulcerations resembling PG, erythema nodosum, ulcerated nodular lesions, granulomatous vasculitis, erythema induratum, papulonecrotic eruptions, papular lesions resembling lupus erythematosus, multiform erythema, urticaria, Raynaud phenomenon and postgranulomatous anetoderma after healing (12, 13, 16, 24, 25, 26).

In most patients, active pulseless disease preceded the manifestation of PG (actually SUV). Our case, as the patient of Dagan et al. (14) the marked PG occurred 3 years before the vascular lesions of pulseless disease. Interestingly, the location of the skin lesions in patients with pulseless disease did not correlate with the site of the large vessel arteritis (10, 13). In our patient, the cutaneous SUV healed with postgranulomatous anetoderma after immunosuppressive therapy, as pulseless disease became apparent with occlusion of the large vessels of aortic arch.

Relapsing of cutaneous ulcerations and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate are indicators for activity at any stage of the disease (13, 27). Immunoglobulin M and G antibodies against arterial media were found by indirect immunofluorescence in patients with association of PG and TA (9). It is hypothesised that both the cutaneous alterations and the arterial obtrusions are caused by autoantibodies against elastin (9, 14, 25). An association of pulseless disease and glomerulonephritis has been reported (28).

There is no specific treatment for PG and pulseless disease despite the apparent plethora of treatment modalities (14, 15, 21, 29, 30, 31, 32). Systemic therapy with corticosteroids is the primary treatment of choice for patients with PG and TA (14, 15). However, many therapeutic agents conventionally effective in PG as corticosteroids, sulphones, clofasamine, thalidomide, etc. failed to suppress the disease activity in our patient. Steroid‐resistant patients with PG and TA have been reported (33, 34). In corticosteroid‐resistant PG and pulseless disease, immunosuppressive therapy with methotrexate has been tried with varying success (25, 28, 31). In our case, a prolonged treatment by methotrexate was achieved with recurrence of new lesions upon withdrawal. The patients with chronic relapsing disease present especially difficult skin management problems. Cyclosporin A efficacy in severe recalcitrant cases of PG and TA has been reported (15, 21). We observed hypertrichosis, gingival hyperplasia and depression as side‐effects of cyclosporin therapy in our patient. It is difficult to conclude what is the cause of this interstitial glomerulonephritis in our patient, association with PG or side‐effect of cyclosporin A therapy. In our case, cardiosurgery specialists refused reconstructive operation due to persistent of inflammatory process in the main branches of aorta.

There are three conceptions for this entity: (a) it is a clinical variant of PG (1, 20, 29); (b) it is a cutaneous manifestation of WG (5, 16, 17, 18, 35, 36, 37, 38); and (c) it is a separate entity that is due to obliteration of great arteries (2, 6, 7). Our case confirmed the last two as correct. Hence, a more suitable name, SUV.

Thus, we describe a patient with cutaneous SUV of the face and neck recalcitrant to conventional therapy, who developed pulseless disease and died at 19 years of age. A good response of the skin lesions was achieved with methotrexate, followed by cyclosporin A. But despite this treatment for 4 years, the disease evolution continued with a fatal outcome. We believe that the term SUV is appropriate for such cases with these cutaneous manifestations and WG, TA or other medium‐to‐large vessel vasculitis.

References

- 1. Perry HO, Winkelman RK, Miller SA et al. Malignant pyoderma. Arch Dermatol 1968; 98: 561–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Powell F, Winkelmann RK. Malignant pyoderma. Br J Dermatol 1983;109: 597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Salassa JR, Winkelmann RK, McDonald TJ. Malignant pyoderma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1982;89: 917–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee CT, Thirumoorthy T. A case of malignant pyoderma with neurological manifestations. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1988;17: 554–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gibson LE, Daoud MS, Muller SA, Perry HO. Malignant pyodermas revisited. Mayo Clin Proc 1997;72: 734–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wernikoff S, Merrit C, Briggman RA, Woodley DT. Malignant pyoderma or pyoderma gangrenosum of the head and neck? Arch Dermatol 1987;123: 371–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Erdi H, Anadolu R, Piskin G, Gurgey E. Malignant pyoderma: a clinical variant of pyoderma gangrenosum. Int J Dermatol 1996;35: 811–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoshida H, Ito F, Miura K et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Three cases with circulatory distrubances. Jpn J Dermatol 1966;76: 435–59. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shinkai H, Mori Y, Nishioka G. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with aortitis syndrome. Rinsho Dermatol 1970;12: 773–85. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hidano A, Watanabe K. Pyoderma gangrenosum et cardiovasculapathies en particulier arterite de Takanyasu. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1981; 108: 13–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohta Y, Ohya Y, Fujii K et al. Inflammatory diseases associated with Takayasu's arteritis. Angiology 2003;54: 339–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chaffai M, Hanza M, Bnouni B et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum au cours d'une arterite de Takayasu. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1982; 109: 755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frances C, Boisnic S, Bletry O et al. Cutaneous manifestations of Takanyasu arteritis: a retrospective study of 80 cases. Dermatologica 1990;181: 266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dagan O, Batak Y, Metzker A. Pyoderma gangrenosum and sterile multifocal osteomyelitis preceding the appearance of Takayasu arteritis. Pediatr Dermatol 1995;12: 39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fearfield LA, Ross JR, Farrell AM et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Takayasu's arteritis responding to cyclosporin. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141: 339–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Szczerkowska‐Dobosz A, Roszkiewicz J. Wegener's granulomatosis—pyoderma gangrenosum type. Przegl Dermatol 2001; 88: 163–69. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doaud MS, Gibson LE, Dahl PR et al. Cutaneous Wegener's granulomatosis presenting as pyoderma gangrenosum‐like ulceration. Eur J Dermatol 1995; 5: 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perry HO. Contravesies in bullous pyoderma gangrenosum, plaque‐like cutaneous mucinosis and malignant pyoderma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1997;9 (Suppl. 1):S33. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cone LA, Annunziata GM, Gebhart RN. Malignant pyoderma and Wegener's granulomatosis. Mayo Clin Proc 1998;73: 390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spenatto N, Viraben R. Malignant pyoderma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1999;12: 275–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cardinali C, Giomi B, Caproni M, Fabbri P. Guess what! Malignant pyoderma responding to cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol 2001;11: 595–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Savory WS. Case of a young woman in whom the main arteries of both upper extremities and of the left side of the neck were thought complementary obliterated. Med Chir Trans Lond 1856;39: 205–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takayasu M. Case with unusual changes of the central vessels in the retina. Acta Soc Ophthalmol Jpn 1908;12: 554–58. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Perniciaro C, Winkelman RK, Hunder GG. Cutaneous manifestation of Takayatsu's arteritis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1987;17: 998–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Taieb A, Dufillot D, Pellegrin‐Carloz B et al. Postgranulomatous anetoderma associated with Takayasu's arteritis in a child. Arch Dermatol 1987;123: 796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pascual‐López M, Hernández‐Núñez A, Aragüés‐Montañés M et al. Takayasu's disease with cutaneous involvement. Dermatology 2004; 208: 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishikawa K, Maetani S. Long‐term outcome for 120 Japanese patients with Takayasu's disease. Circulation 1994;90: 1855–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zilleruelo GE, Ferrer P, Garcia OL. Takayasu's arteritis associated with glomerulonephritis. Am J Dis Child 1978;132: 1009–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Powell F, Su D, Perry H. Pyoderma gangrenosum: classification and management. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34: 395–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dourmishev AL, Miteva L, Schwartz R. Pyoderma gangrenosum in childhood. Cutis 1996;58: 257–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mevorach D, Liebowitz G, Brezis M et al. Induction of remission in a patient with Takayasu's arteritis by low dose pulses of methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis 1991;51: 904–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pari T, George S, Jacob M et al. Malignant pyoderma responding to clofazimine. Int J Dermatol 1996;35: 757–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kerr GS, Halahan CW, Giordano J et al. Takayasu's arteritis. Ann Intern Med 1994;120: 919–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hoffman G. Treatment of resistant Takayasu's arteritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1995;21: 73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thomas RH, Payne CME, Bleck MM. Wegener's granulomatosis presenting as pyoderma gangrenosum. Clin Exp Dermatol 1982; 7: 123–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lerner EA, Dover JS. Malignant pyoderma: a manifestation of Wegener's granulomatosis? J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;15: 1051–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Micali G, Cook B, Ponan S et al. Cephalic PG‐like lesion presenting signs of Wegener's granulomatosis. Int J Dermatol 1994;33: 470–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kihiczak D, Nychay SG, Schwartz RA, McDonald RJ, Churg J, Lambert WC. Protracted superficial Wegener's granulomatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;30: 863–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]