Abstract

Wound clinics are seeing an increase in the number of ‘complex’ wounds, which arise as the result of the interaction between multiple coexisting systemic pathologies, environmental factors and local wound factors. These complex wounds require an approach to diagnosis and management that can encapsulate all these factors. Unified wound assessment approaches such as HEIDI (History, Examination, Investigations, Diagnosis and management plan), wound bed preparation and applied wound management systems are essential to reach a definitive diagnosis and to ensure that management is agreed between the various clinical specialities that may be involved. A series of case histories is presented that illustrate the benefits of a unified approach to wound management. Results of a study into the cost‐effectiveness of an improved foam dressing are presented, and the problems of demonstrating the ability to make long‐term savings through short‐term expenditure are discussed.

Keywords: Applied wound management, Complex wounds, Evidence base, Fluid handling, HEIDI, Randomised control trials (RCTs), Wound bed preparation

Introduction: meeting the challenge of a changing patient profile

Medical advances in the management of common chronic conditions mean that individuals are living longer, often with reasonable – if not perfect – health. Infection, respiratory conditions and arthritis result in early mortality or disability, but now people survive well into their 70s and 80s even if with significant pharmacological support. The impact of this trend on wound management is enormous: there is a growing number of complex wounds – usually in patients with poor general health – that develop as a result of multiple systemic pathologies. Often the only way to improve wound healing in these cases is to improve the overall health of the patient.

Wound management has developed almost beyond recognition in the past 20 years, although not necessarily with the support of rigorous evidence. In the early days, if there was any strategy at all, it was to ‘cover and conceal’(1). Moist wound healing was a new and radical concept that took a while to become accepted (2), and the latest thinking in wound management originated in the all‐embracing theory of wound bed preparation (3).

This transition in wound management is reflected in the therapies that are now available. The principle of cover and conceal implies that all that can be done for a wound is to manage it with a dressing, while in reality, wound healing may only be achieved by attending to a patient’s nutrition, mattress and psychological status and blood sugar levels or a host of other factors including debridement, infection control and moisture handling.

When patients present with complex pathologies, it is often the case that complete wound closure is an unrealistic goal; perhaps, the most that can be achieved is the management of symptoms. It is important to be realistic: attempt to heal where appropriate but be satisfied with controlling symptoms when healing is unlikely.

Wound assessment

Wound assessment used to be confined to an assessment of the size of the wound; clinical assessment – if carried out at all – would be filed separately from wound assessment with little apparent understanding that the two may be linked (4). Wound assessment has become much more comprehensive, although agreement on which are the most appropriate wound healing parameters to monitor has yet to be reached (5). There is now the risk of a movement in the opposite direction: as the assessment procedures become more complex and all embracing, clinicians will find it too time‐consuming to carry out thorough assessment. However, increased awareness and rising litigation have stimulated the agreement of care protocols that mandate an accurate assessment of wounds.

A number of methods are available for wound assessment. These are mainly applied to pressure ulcers, although some are applicable to other wound types:

-

•

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP)/Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) staging system. (6)

-

•

PSST: Pressure Sore Status Tool, automated version known as the Wound Intelligence System (7)

-

•

PUSH: the NPUAP Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing (8)

-

•

WHS: Wound Healing Scale developed by Krasner to provide an alternative to the reverse staging necessary with other systems when monitoring healing (9)

-

•

SWHT: Sussman Wound Healing Tool (10)

These systems are not entirely compatible with each other, and it is not easy to see how they can all be accommodated into one system. A choice has to be made as to which is the most appropriate for an individual unit and its caseload. The challenge is to find a system that can be used easily at the bedside, does not require complex equipment, incorporates an assessment of systemic and regional as well as local factors, and is flexible enough to describe the full spectrum of wounds likely to be encountered in most wound clinics.

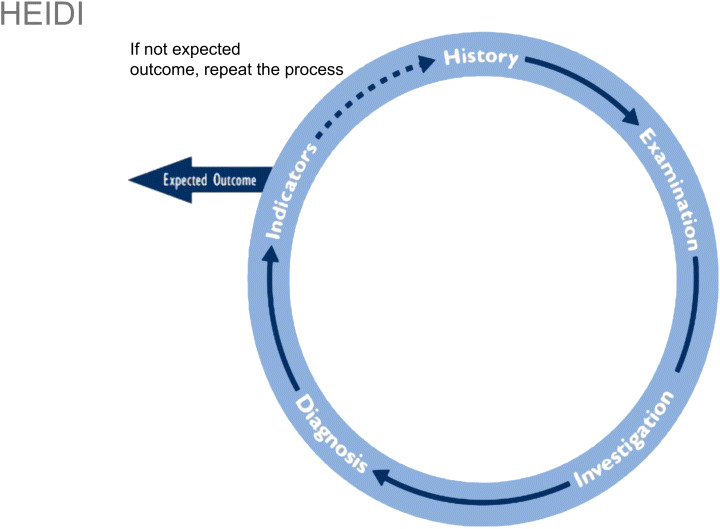

One simple reminder of how to carry out a systematic assessment is to use the HEIDI mnemonic, which stands for History, Examination (11), Investigations, Diagnosis and management plan, and the Indicators that we would expect for each patient (Figure 1). If the expected outcome is not achieved after following the assessment path and treating the patient, then the assessment process should be repeated.

Figure 1.

The HEIDI mnemonic for wound assessment and management (11).

Although it is important to treat the whole patient to heal a wound, this may require a radical shift in one’s approach. Instead of following one management plan through from admission to discharge, the goal at each stage may change depending on the changing status of the patient. Initially, the background disease may be targeted, while 2 weeks later, it may be necessary to manage the symptoms of the wound. But it is essential to recognise the systemic, regional and local factors that influence healing and to deal with them as well as local wound factors. This principle underpinned the development of the wound bed preparation approach (3).

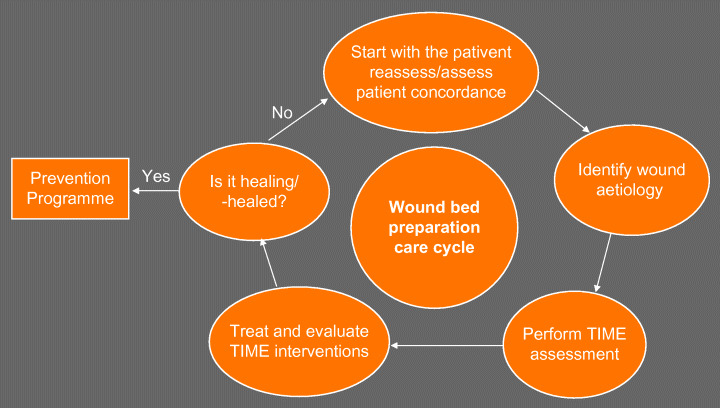

As interest grew in the concept of wound bed preparation, an international, multidisciplinary board of experts reviewed the scientific basis for this approach and agreed both a definition and the essential components (12). The wound bed preparation care cycle – like HEIDI – involves an initial assessment of the background status of the patient before the condition of the wound is assessed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Wound bed preparation care cycle (30).

The same group of experts went on to develop an easy and systematic means of assessing the wound called TIME 12, 13. This guides the user through an assessment of the tissue, infection/inflammation, moisture and edge of the wound to identify the local factors that may be impairing wound healing. In the TIME table, a simple description of the underlying pathology for each of these stages is given, along with recommended clinical actions and the desired clinical outcome should these actions be successful. Just as with HEIDI, the TIME process is iterative, so that if the desired outcomes are not achieved, the clinician will go back round the loop with another assessment. The TIME table provides a useful framework when looking at the wound itself, and it is a very quick system to use.

Whichever method is used, there is little doubt that optimal care will only arise when the method of assessment is carried out in a practical and systematic manner. At Aberdeen hospital, a system called the Applied Wound Management System (14) is used. This is based on the same elements as TIME (tissue, infection and moisture). Information about the wound is entered directly into the patient record database in the form of a wound healing continuum. The status of the tissue is recorded on a continuum ranging from black to pink. The infection continuum ranges from colonisation to spreading infection, while the exudate continuum records not just the quantity but also the viscosity of the exudate.

Wound management in a multidisciplinary environment

It can be particularly difficult to manage patients with multiple pathologies, in that what is seen as optimal care by one speciality can be seen as detrimental by colleagues in another. Comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease have a great impact on how wounds are managed. The first case is a good illustration of the type of complex wound increasingly seen in wound clinics and shows the value of a systematic assessment process in reducing complex cases to their essential components. This patient was referred to the wound clinic at Aberdeen with a diagnosis of ‘cellulitis’ (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Patient referred with supposed cellulitis.

A swab was taken from the wound and the results appeared to confirm the initial diagnosis. However, this was the wrong assumption to make, as was illustrated by working through the wound assessment process (Table 1).

Table 1.

Assessment of patient referred with supposed cellulitis

| Category | Systemic/patient factors | Local/wound factors | Treatment plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| History | No history of leg ulcer, Widespread osteoarthritis, Recurrent depression | Wound three days in duration, daily size increase | |

| Examination | Movement at joints, deformity, pulses, temperature | High levels of pain; T = black/yellow; I = none; M = high volumes, low viscosity; E = erythema at margins, further breakdown | |

| Investigations | Full blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, autoantibodies, U + E, liver function tests, C‐Reactive Protein test, X‐ray, duplex | Wound biopsy, wound swab | |

| Diagnosis | Vasculitic leg ulcers | Vasculitic leg ulcers | Oral steroids, immunosuppression, pain management, debridement, exudate management, wound mapping/photography, dietetic referral |

| Indicators | Change in blood values | Review wound assessment. Are we progressing? | Wound mapping/photography, reassess |

All the indicators from a systematic assessment of this patient pointed towards a vascular problem. There was no increase in temperature, which would have been expected with cellulitis, and there was a lot of dead tissue and high levels of exudate at the wound. The history provided useful information that could be used to confirm as well as to exclude possible diagnoses. The renal function was important in case this was contributing to skin breakdown. A scan would show if there was evidence of osteomyelitis. The level of pain was important because of ischaemia rather than infection or inflammation; however, the wound swab was misleading as it had been taken from the surface of the wound, rather than deeper tissue.

Having established that the diagnosis was a vasculitic leg ulcer, rather than cellulitis, the preferred therapy was oral steroids, but this was risky given the patient’s general condition, so topical steroids were applied instead. The aims of treatment were to control the pain, achieve effective debridement and manage the exudate.

A second illustration is provided by a patient who was referred with the diagnosis of venous leg ulceration (Figure 4). The patient had a 4‐week history of varicose eczema and 2 weeks’ treatment with paste bandages. There had been bleeding from the wound for 2 weeks. Because of the condition of the skin at the ankle, it was impossible to carry out a Doppler exam to confirm the diagnosis, but before referral, a Doppler had been taken, and the clinician assumed a diagnosis of venous leg ulcer and applied compression bandaging.

Figure 4.

Patient referred with supposed venous leg ulcer.

A thorough assessment showed that the patient had cardiac failure, a history of venous leg ulceration and evidence of bandage trauma (Table 2).

Table 2.

Assessment of patient referred with supposed venous leg ulcer

| Category | Systemic/patient factors | Local/wound factors | Treatment plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| History | Cardiac failure, dementia, previous venous leg ulcer | 4 weeks varicose eczema, 2 weeks paste bandages, 2 weeks bleeding from wound | |

| Examination | Pulse, electrophysiology test chest, heart sounds, degree of oedema | Open wounds across both limbs; bandage trauma; oedema in both lower limbs, mild pain; T = red; I = colonised; M = high/low | |

| Investigations | Chest X‐ray, full blood count, U + Es, patch test | Repeat Doppler | |

| Diagnosis | Contact eczema, heart failure | Control heart failure, pain management, skin care/topical steroids, elevate lower limbs, atraumatic contact layer, absorbent pads, Softban, toe‐to‐knee retention stocking | |

| Indicators | Control of oedema, control of erythema | Review wound assessment. Progress? | Wound mapping/photography, reassess |

As a result of the assessment, it was clear that the previous compression bandaging had had the effect of forcing the fluid, because of heart failure, into the feet and the wounds were not because of venous leg ulcer but because of contact eczema and trauma from the compression bandaging. The patient’s cardiac failure was deteriorating, and the key to healing the wounds was to control this. Working with colleagues in cardiology, it was possible to improve the patient’s cardiac failure and to use elevation, soft contact layers and skin creams for local wound care.

Another example illustrates how broad the concept of wound management has become. It shows how the priorities in wound healing may shift many times during the course of patient management, dictated by the findings of the assessment process. This is often the case when dealing with patients with multiple pathologies who may have quite specific requirements regarding their quality of life. This example shows the flexibility that is needed to manage these patients and that the ultimate desired outcome may not necessarily be wound healing – particularly if that can only be achieved through lifestyle changes that the patient will find unacceptable.

The patient shown in Figure 5 was transferred from the spinal cord injury unit with a pressure ulcer. The necrotic tissue in this wound provides an ideal breeding ground for bacteria, which increase the level of proteases in the wound and constantly degrade the extracellular matrix (15). There is a poor local vascular supply and cell senescence leading to the accumulation of devitalised tissue. This patient was relatively young, only 50 years, and had been paraplegic for 30 years since a motorbike accident, with frequent recurrences of this pressure ulcer over a period of 25 years. However, careful questioning revealed that the pressure ulcer was because of circumstances in the patient’s life that increased the risk for developing pressure ulcer.

Figure 5.

Paraplegic patient with pressure ulcer.

This patient enjoyed fishing, so his friends would take him to a good fishing spot and allow him to sit on the bank all day and sometimes overnight – without a pressure relieving cushion. He was provided with a properly designed cushion and together with appropriate dressings, the ulcer began to heal. The cushion prevented further damage. For patients like this, there can be no question of depriving them of what may be the only remaining pleasure; the main therapeutic goal must be to help them enjoy a fulfilling life without putting themselves at further risk.

The next patient was referred for review of a supposedly superficial pressure ulcer. She was aged 72 years and had come from a nursing home. She was overweight but undernourished and had low serum albumin level, poor electrolyte levels and arrhythmias. The lady had a sacral ulcer that was not at all superficial, dry and with undermined areas. The patient was also clearly depressed. The patient and wound were assessed, and, using the TIME framework, it was clear that the cavity had deep tissue damage, there were no obvious signs of infection and the wound was too dry, certainly not macerated. The wound edge was poorly defined, and the wound had to be exposed to find out what lay beyond the immediately visible non viable tissue (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Nursing home patient with presumed superficial pressure ulcer.

As a first step, Intrasite gel was applied, with Allevyn to cover the sacrum. Alginate or hydrofibre dressings were avoided in case they became trapped in the cavity, while Intrasite gel is inert and will fill the gap, allowing debridement. Allevyn was used to promote a moist wound environment. Most importantly, the patient was referred to a dietician and a physician addressed the multiple medications. As the wound progressed, there was a concern about the friable dark granulation tissue, but by week 2, there was visible healthy granulating wound and the patient was suitable for discharge. However, she did not go back to the nursing home. There, many patients had Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia and the patient – who was a former teacher and still an avid reader – had no stimulation from fellow residents. On discharge, the patient was moved to a residential home that helped her psychologically by allowing her greater independence and interaction.

In conclusion, these cases illustrate the complexities of managing patients with ulcers. Assessment and flexibility of approach are essential: if the status of the wound or the patient changes, the management goals must also change. It is also important to recognise that full wound closure may not be achievable.

Dressing options: balancing different needs

The complexity of many wounds and the need for multiple approaches are placing greater demands on the tools that are used in wound healing. This is particularly evident in the need for advanced and multifunctional dressings. Dressings do not just provide a barrier between the wound and the environment: depending on the situation they may be required to carry out debridement, to deliver antimicrobials to the wound, to keep the wound moist and to provide compression or physical support, or many other functions. Additionally, if it is to be left in place for any length of time, the dressing should be comfortable for the patient, should stay in place without aggravating the surrounding skin and should make it possible for the patient to keep clean. These are significant demands, and manufacturers have made great attempts to provide dressings that meet these requirements.

However, the sheer diversity of the available dressings can cause difficulty: with so many different dressings available, it is not surprising that some clinicians stick with one or two that they are familiar with and ignore the very real developments that have taken place elsewhere. The main types of dressing, along with their primary functions, are summarised in Table 3. It is interesting that none of them is claimed to heal a wound. This perhaps reflects an understanding of the complex nature of wounds and that it is unrealistic to expect one single topical intervention to bring about total healing.

Table 3.

Dressings and their function

| Type of dressing | Function |

|---|---|

| Films | Superficial protection |

| Foams | Protection, absorbency |

| Hydrogels | Debridement, rehydration |

| Hydrocolloids | Debridement, protection |

| Alginates | Absorbency, haemostasis |

| Medicated dressings | Exudate handling, infection control |

Harding (28).

Part of a systematic approach to wound management must include appropriate selection of dressings, with the question ’what is needed from this dressing’? It may be debridement, support, protection, infection control, moisture handling or even compliance, conformability, patient acceptability or long wear time. If these questions are not asked, the wound may fail to progress. Ovington (16) provided some excellent guidelines for choosing wound dressings that are still valid today (Table 4).

Table 4.

Choosing a dressing

| Use a dressing that will maintain a moist environment |

| Use clinical judgement to select a moist wound dressing for the wound being treated |

| Choose a dressing that will keep the peri‐ulcer skin dry while maintaining the moisture within the wound |

| Use a dressing that will control the wound exudate without leading to desiccation of the wound bed |

| If possible, use dressings that are easy to apply and do not require frequent changes as this will decrease the amount of health care provider time required |

| Fill any cavities within the wound to avoid impaired healing and increased bacterial invasion |

| Monitor all dressings, particularly those near the anus, which are difficult to keep in place |

Ovington (16).

In addition to these guidelines, it is important to review the dressing regimen regularly to reflect the changes taking place in the wound.

Managing moisture in the wound is particularly challenging. Systemic factors such as congestive heart failure will increase oedema and fluid production, as will lymphoedema and immobility, and local factors such as infection. Even when these are addressed, products are still needed that can handle large amounts of fluid without producing strike through after only a short amount of wear. One of the early concerns about moist wound healing was that this technique would lead to maceration of the wound and could simply create an environment in which bacteria could flourish (17).

These fears were understandable in the light of increasing knowledge about chronic wound fluid. Chronic wound fluid is biochemically distinct from acute wound fluid and is known to slow down or even block the proliferation of key wound cells such as keratinocytes, fibroblasts and endothelial cells. A number of publications report that chronic wound fluid inhibits proliferation of fibroblasts 18, 19, prevents cell adhesion and migration of cells across the wound bed (20), maintains the inflammatory response (3) and contains macromolecules that are capable of trapping the growth factors that direct cell proliferation and high levels of matrix metalloproteinases that destroy or corrupt newly formed matrix 15, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25.

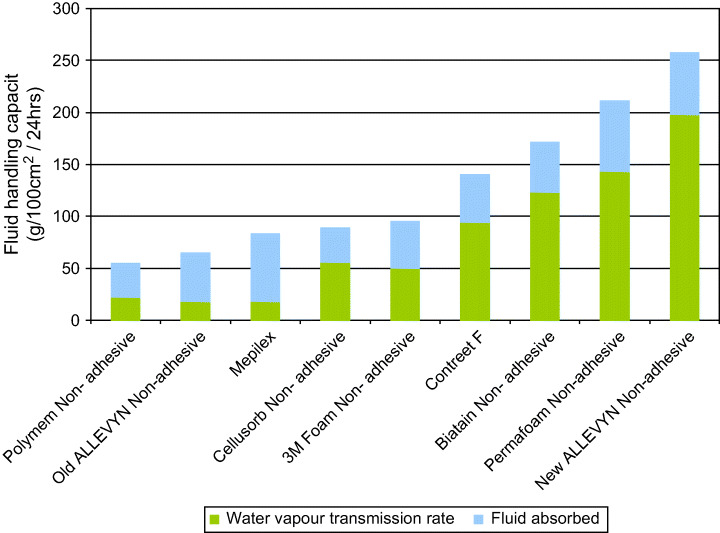

In these circumstances, the ideal dressing will be able to draw away components of chronic wound fluid by providing good fluid handling capacity while maintaining a moist environment at the wound bed by controlling the combination of absorption and moisture vapour transmission rate. Fluid handling capacity is an essential component of dressings for chronic wounds, with great variation between the various dressings available (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Fluid handling capacity of a range of non adhesive dressings (Smith & Nephew, Data on file).

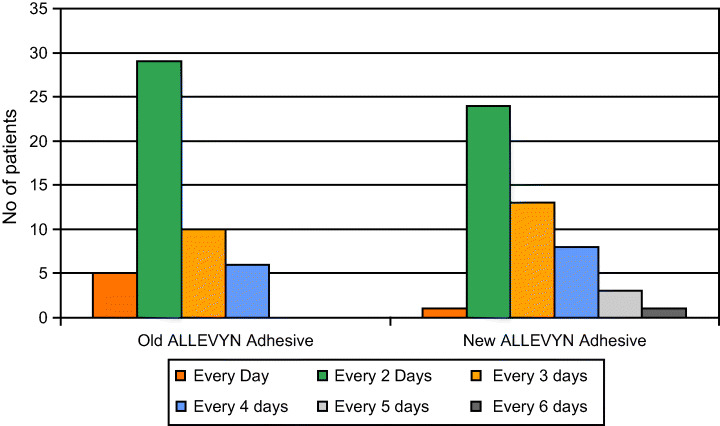

Of these dressings – Allevyn – has been recently improved to increase its fluid handling capacity and rate of fluid uptake. Between May and September 2005 Theresa Hurd (Niagara, Canada) carried out an evaluation of the adhesive variant of enhanced Allevyn both in vitro and clinically. There were 50 patients in the clinical sample: 23 surgical wounds, 12 pressure ulcers, 13 diabetic foot ulcers and 2 malignant wounds. Allevyn Adhesive was assessed against the earlier version of Allevyn Adhesive for its fluid handling capacity and wear time. This enabled an assessment to be made of cost‐efficiency, and the impact this had on the number of nursing visits required in a 1‐month period. It was found that the new Allevyn Adhesive showed a marked increase in wear time (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Wear time of Allevyn versus Allevyn Adhesive in a sample of 50 patients (Smith & Nephew, Data on file).

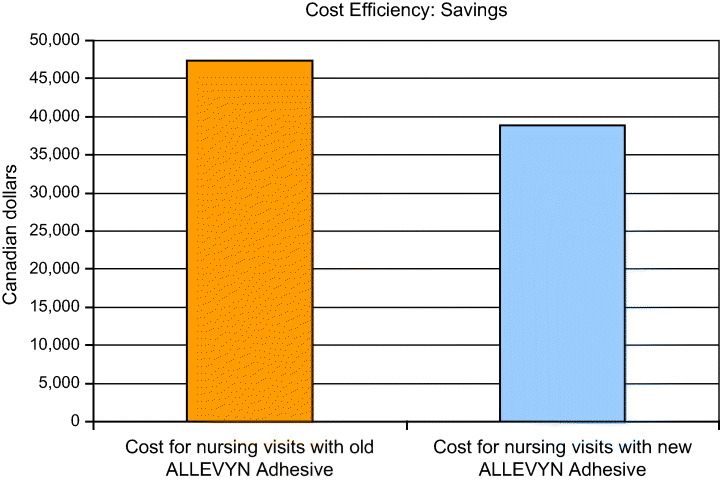

The total number of nursing visits required to manage the patients wearing new Allevyn Adhesive (600 visits) was substantially less than that required to manage the patients with the older Allevyn (700 visits), showing that advanced dressings can repay the purchase cost in terms of the savings to be gained in other areas (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Cost savings to be made with longer wear time of foam dressing (Niagara Community Care, data on file, 2006).

No dressing is perfect for every wound, but in this Canadian clinic, there have been many patients for which the new Allevyn Adhesive foam dressing is ideal. The typical daily caseload in this Community Care Access Centre is 3300 patients, of whom up to 1700 have chronic wounds. Around 16% of these are pressure ulcers, and 80% of these are located on the heel.

A patient was admitted with a high trauma fracture on the exterior of the ankle (Figure 10). These are exceptionally painful fractures that are exacerbated by the slightest movement, and in this case, pain was made worse by underlying osteomyelitis. The patient responded very well to the support and comfort of the new Allevyn Adhesive and appreciated the reduced frequency of dressing changes.

Figure 10.

Patient with high trauma ankle fracture.

A final case has similarities to the patient who wanted to continue fishing (above). This woman has spina bifida and presented with pressure ulcers on her knees that had persisted for a year, despite experimentation with a variety of dressings (Figure 11). The main omission in her care was that no one had investigated the reason why she had pressure ulcers on her knees in the first place. It emerged that she was in the habit of dropping forward out of her wheelchair onto her knees in order to change her own briefs: she was 23 years old and wanted to retain this small act of independence. Pressure relieving surfaces were found for her to enable her to carry on doing her own changing. With hindsight, it was clear that no dressing was going to resolve a problem like this.

Figure 11.

Pressure ulcers located on knees of wheelchair‐bound spina bifida patient.

Best practice in wound management

It can be difficult and uncomfortable to review one’s own management of chronic wounds. Is it based on a theoretical understanding of what is going on in a wound? Or is it based on anecdote and individual experiences?

This is an understandable way of working, but all physicians are now required to operate with regard to evidence – where it exists. Published evidence is often used to inform financial decisions, and it can be hard to offer optimal care that falls outside of the evidence base, without being challenged on the grounds of cost or resource minimisation or control.

Where is the experimental data to underpin practice in wound management? Many people believe that the randomised controlled trial (RCT) is the only worthwhile form of evidence, along with systematic reviews or meta‐analyses. However, Concato et al. (26) challenged this consensus about the hierarchy of study designs in an interesting study that compared the results of meta‐analyses of RCTs with meta‐analyses of cohort and case–control studies for each of five interventions. They found that the average results of the observational studies in all cases were very similar to those of the RCTs and concluded that the average results from well‐designed observational studies (cohort or case–control design) do not systematically overestimate the magnitude of effect when compared with results from RCTs of the same topic. They also found that, viewed individually, there was less heterogeneity in the results from observational studies, whereas among the RCTs, some studies reported results in a direction opposite to that of the pooled results.

The possible reasons for these findings are that observational studies usually include patients with coexisting illnesses and a wide range of disease severity. Treatment is tailored to the needs of the individual patient, unlike the protocol in a single randomised trial (27). There can also be problems with applying the results from RCTs to clinical practice. The highly controlled nature of RCTs often means that they have little relevance to the type of patient most commonly seen in the clinic or the way in which they are managed.

Each RCT will include a group of patients strictly defined by the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the treatment protocol may not represent normal clinical practice. The typical patient in an RCT is between the ages of 18 and 65 years, has few comorbidities and is receiving only a limited range of comedications. This profile is highly unrepresentative of a typical clinical caseload, and the actual clinical relevance of the study to the wider population of patients may approach zero. This is particularly so in chronic wound management – stringent patient selection in clinical studies often excludes the very people that form the typical clinical caseload: elderly patients with multiple disease pathologies such as diabetes, arthritis, heart failure, asthma and peripheral vascular disease, who are taking a number of medications for these conditions (27).

Restrictions on the therapies that can be given – which would otherwise be confounding factors in a trial – are often precisely what is needed as therapy is adjusted based on the patient’s response. Ironically, Archie Cochrane, who first labelled the RCT as the ‘gold standard’ of clinical investigation confessed in his diary that, while serving in the army, a single case study changed his practice.

However, the RCT is still held up by many health care purchasers to be the only acceptable form of evidence for effect or cost‐effectiveness. Purchasing constraints on pressure relieving equipment are common; yet, the money saved through providing appropriate pressure relieving mattresses or appliances can more than save the original purchase cost. It is not uncommon for a patient with diabetes to be admitted to hospital, perhaps with a hip fracture, and to be discharged with a heel ulcer. If the patient’s glycaemic control is poor, the ulcer can deteriorate, leading to a return to hospital and the possibility of amputation. Purchasing constraints make it exceptionally difficult to buy newer dressings or pressure relieving systems but the cost of treating a grade 4 pressure ulcer in the UK, for example, averages over £ 10 000. A single case of osteomyelitis may cost more than £ 24 000 (28).

Pressure sores affect up to 18% of the population in general acute care; 28% in long term care and 29% in home care (29). The majority are preventable, and the cost of repairing the damage caused by pressure ulcers amounts to 4% of UK health care spending. Given this social and economic burden, it is surely worth investing in measures to prevent pressure ulcers forming rather than in repairing the damage. Studies such as the one conducted by Theresa Hurd help to make a case for improved dressings but more are needed.

Conclusion

Patients are presenting with increasingly complex pathologies and multiple comorbidities at wound clinics. Often, local wound management alone will be incapable of bringing about wound healing, which can only be achieved by resolving coexisting systemic diseases. Further complexity is introduced by the need to ensure that therapies used to treat the wound do not exacerbate any of the coexisting problems. A unified approach to wound assessment that incorporates systemic, regional and local factors is the key to diagnosis in these patients and to successful management. Significant demands are placed on topical therapies, including dressings, which are now expected to fulfil increasingly advanced roles.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

This article is a supplement based on presentations given at meetings of the EPUAP (European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, Berlin, 31 August 2006) and EWMA European Wound Management Association, Prague, 18 May 2006) by Prof. Keith Harding, David Gray, John Timmons and Theresa Hurd.

References

- 1. Ovington L. Advances in wound dressings. Clin Derm 2007;25:33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Winter GD. Formation of scab and the rate of epithelialisation of superficial wounds in the skin of the young domestic pig. Nature 1962;193:293–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Falanga V. Classifications for wound bed preparation and stimulation of chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2000;8:347–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hess CT. The art of skin and wound care documentation. Adv Skin Wound Care 2005;18:43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Keast DH, Bowering K, Evans AW, MacKean GL, Burrows C, D’Souza L. MEASURE: a proposed assessment framework for developing best practice recommendations for wound assessment. Wound Rep Regen 2004;12:S1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. AHCPR Panel for the Prediction and Prevention of Pressure Ulcers in Adults . Clinical practice guideline number 3: pressure ulcers in adults: prediction and prevention. Rockville: US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1992. (AHCPR Publication number 92‐0047). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bates‐Jensen BM. Pressure ulcer assessment and documentation: the pressure sore status tool. In: Krasner D, Kane D. Chronic wound care, 2nd edn. Wayne: Health Management Publications Inc., 1997:38. [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) . PUSH tool information and registration form [WWW document]. URL www.npuap.org/pushins.htm (NPUAP web site) [accessed on 23 February 2006].

- 9. Krasner D. Pressure ulcers: assessment, classification and management. In: Krasner D, Kane D. Chronic wound care, 2nd edn. Wayne: Health Management Publications Inc., 1997:152–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sussman C, Bates‐Jensen B. Tools to measure wound healing. In: Sussman C, Bates‐Jensen B Wound care. A collaborative practice manual for physical therapists and nurses. Gaithersburg: Aspen Publishers Inc., 1998:103. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heinrichs, Llewelly and Harding in Wound Healing: A systematic approach to wound healing and management. Eds Gray, D and Cooper, P , Wounds UK, Aberdeen, UK, 2006; pp 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schultz GS, Sibbald RG, Falanga V, Ayello EA, Dowsett C, Harding K, Romanelli M, Stacey MC, Teot L, Vanscheidt W. Wound bed preparation: a systematic approach to wound management. Wound Rep Regen 2003;S11:1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schultz GS, Mozingo D, Romanelli M, Claxton K. Wound healing and TIME: new concepts and scientific applications. Wound Rep Regen 2005;13:S1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gray D, Cooper P, White R, Kingsley A. Applied Wound Management: a clinical decision making framework. Wounds UK 2004; Applied Wound Management 2004:S31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Trengove NJ, Stacey MC, MacAuley S, Bennett N, Gibson J, Burslem F, Murphy G, Schultz G. Analysis of the acute and chronic wound environments: the role of proteases and their inhibitors. Wound Repair Regen 1999;7:442–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ovington L. Dressings and adjunctive therapies: AHCPR guidelines revisited. Ostomy Wound Manage 1999;45:S94–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hutchinson JJ, Lawrence JC. Wound infection under occlusive dressings. J Hosp Infect 1991;17:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bucalo B, Eaglstein WH, Falanga V. Inhibition of cell proliferation by chronic wound fluid. Wound Rep Regen 1993;1:181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Loots MA, Lamme EN, Mekkes JR, Bos JD, Middelkoop E. Cultured fibroblasts from chronic diabetic wounds on the lower extremity (non‐insulin dependent diabetes mellitus) show disturbed proliferation. Arch Dermatol Res 1999;291:93–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lerman OZ, Galiano RD, Armour M, Levine JP, Gurtner GC. Cellular dysfunction in the diabetic fibroblast: impairment in migration, vascular endothelial growth factor production, and response to hypoxia. Am J Pathol 2003;162:303–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lobmann R, Ambrosch A, Schultz G, Waldmann K, Schieweck S, Lehnert H. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in the wounds of diabetic and non‐diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2002;45:1011–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wysocki A, Staiano‐Coico L, Grinnell F. Wound fluid from chronic leg ulcers contains elevated levels of metalloproteinases MMP‐2 and MMP‐9. J Invest Dermatol 1993;101:64–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tarnuzzer RW, Schultz GS. Biochemical analysis of acute and chronic wound environments. Wound Rep Regen 1996;4:321–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bullen EC, Longmaker MT, Updike DL, Benton R, Laedin D, Hou Z, Howard EW. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase‐1 is decreased and activated gelatinases are increased in chronic wounds. J Invest Dermatol 1995;104:236–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yager DR, Zhang LY, Liang HX, Diegelmann RF, Cohen IK. Wound fluids from human pressure ulcers contain elevated matrix metalloproteinase levels and activity compared to surgical wound fluids. J Invest Dermatol 1996;107:743–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz RA. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1887–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Claxton K, Dowsett C. Reviewing the evidence for wound bed preparation. J Wound Care 2006;15:439–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bennett G, Dealey C, Posnett J. The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK. Age and ageing 2004;33:230–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cuddigan J, Beslowitz D, Ayello E. Pressure ulcers in America: Prevalence, incidence and implications for the future. Advances in Skin and Wound Care 2001;14(4):208–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dowsett C, Newton H. Wound bed preparation: TIME in practice. Wounds UK 2005;1(3):58–70. [Google Scholar]