Abstract

Clostridium collagenase has been widely used in biomedical research to dissociate tissues and isolate cells; and, since 1965, as a therapeutic drug for the removal of necrotic wound tissues. Previous studies found that purified collagenase‐treated extracellular matrix stimulated cellular response to injury and increased cell proliferation and migration. This article presents an in vitro study investigating the digestive ability of Clostridium collagenase on human collagen types I, III, IV, V and VI. Our results showed that Clostridium collagenase displays proteolytic power to digest all these types of human collagen, except type VI. The degradation products derived were tested in cell migration assays using human keratinocytes (gold surface migration assay) and fibroblasts (chemotaxis cell migration assay). Clostridium collagenase itself and the degradation products of type I and III collagens showed an increase in keratinocyte and fibroblast migration, type IV‐induced fibroblast migration only, and the remainder showed no effects compared with the control. The data indicate that Clostridium collagenase can effectively digest collagen isoforms that are present in necrotic wound tissues and suggest that collagenase treatment provides several mechanisms to enhance cell migration: collagenase itself and collagen degradation products.

Keywords: Cell migration, Clostridium collagenase, Collagen, Fibroblast, Keratinocyte

INTRODUCTION

Clostridium collagenase is one of several bacterial collagenases that have been widely studied for their biochemical and enzymatic properties. It is a metalloproteinase that is able to digest triple‐helical type I, II and III collagens into simple peptides under physiological conditions 1, 2. Clostridium collagenase contains more than one collagenolytic enzyme in the crude preparation (3). Mandl et al. (4) noted a rapid collagenolysis because of a synergistic attack by two heterogeneous fractions of the enzymes. Kono (5) also found that homogeneous fractions from Clostridium collagenase performed very differently in their ability to degrade insoluble collagen. However, mixtures of the fractions digested the insoluble collagens rapidly and almost completely, indicating that a crude preparation has great potential in applications where digesting insoluble collagens is key. Clostridium histolyticum cultures secrete collagenases that can be precipitated from the medium in relatively large amounts, making the enzyme commercially available for use. In addition to being a valuable tool in the laboratory 6, 7, Clostridium collagenases have found clinical application as a wound debriding enzyme for decades 8, 9. Many cases of successful wound applications of the crude enzyme in an ointment base are illustrated in the treatment of third‐degree burns 10, 11, soft tissue and pressure ulcers 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, diabetic ulcers (17) or venous stasis, and ischemic arterial ulcers 18, 19, 20. These applications with Clostridium collagenase have been shown to provide effective debridement in treating various wounds.

Collagen is the major fibrous protein in the extracellular matrix (ECM) and in connective tissues. In fact, it is the single most abundant protein in the body. There are at least 29 types (21) of collagen, but 80–90% of the collagen in the body consists of types I, II and III. The various collagens are distinguished by the ability of their helical and non helical regions to associate into fibrils, form sheets or cross‐link different collagen types. These fibrous collagen molecules pack together to form long thin fibrils of similar structure. Fibrous‐type collagen molecules (e.g. types I, II and III) assemble into fibrils that are stabilised by covalent aldol cross‐links (22). All types of collagen fold into a characteristic triple‐helical structure established by three polypeptide chains (α chains), which vary between the collagen types. In type I collagen, two types of chains, α1 and α2, are found and form the structure [α1(I)]2 α2(I). Only one α chain is found in type III collagen and the molecular structure is simply [α1(III)]3. Type V collagen is another fibril‐forming collagen with three different α chains [α1(V),α2(V),α3(V)]. Fibril‐forming collagens of types I, III and V are the major collagens in the dermal and connective tissues (23). In dermal tissue, collagen fibrils are hybrids of types I and III collagen molecules. Type I collagen occurs throughout the fibril except for in the periphery, which was coated with type III collagen. Almost no type III collagen was noted in the interior of the collagen fibrils, as it is present only at the periphery (24). Type V collagen represents only 1–3% of the total collagen in the body, and it copolymerises with type I and III collagens to form heterotypic I/III/V fibrils (25).

Unlike the fibril collagens, type IV collagen forms a two‐dimensional reticulum; several other types of collagen associate with fibril‐type collagens, linking them to each other or to other matrix components. Three of six distinct α chains, α1(IV)‐α6(IV), have associated to form the triple helix (26). The predominant form is represented by α1(IV)2 α2(IV) heterotrimers for the essential network. Type IV collagen is the most important structural component of basement membranes, which play a role in cell adhesion and differentiation (27). Keratinocytes in the epidermis secrete type IV collagen to anchor the basal cells and separate the epithelium from the underlying dermal tissue.

Type VI collagen, which is also called a microfibril collagen, is a heterotrimer of three different α chains (α1, α2 and α3) with short helical domains and a rather extended globular termini (28). Among the three α chains, the α3 chain is nearly twice as long as the other chains because of large globular domains at both N‐ and C‐termini (28). It has been reported that type VI collagen represents a major fraction of the connective collagens (29). The biological functions of type VI collagen are not yet fully understood. The study by Keene et al. suggested that type VI collagen microfibrils act as a mechanical link between the interstitial collagens or basement membrane and the surrounding connective tissues (30).

As all the collagen types discussed earlier are present in dermal or connective tissues, when Clostridium collagenase is used for topical treatment, they serve as a pool of prospective substrates for the enzyme's collagenolytic action. Cell migration study was conducted to study in vitro migration behaviour of human keratinocytes and fibroblasts in response to Clostridium collagenase and the various collagen degradation products produced by its actions. The experiments also included a non collagen‐specific protease, trypsin, for comparison.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Unless otherwise indicated, all chemicals and substrates were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich Chemical Company (St Louis, MO). The buffer used was Tris (50 mM) containing 100 mM NaCl and 10 mM CaCl2 (pH 7·4).

Degradation of human collagens by Clostridium collagenase

A Clostridium collagenase solution (produced by DFB Pharmaceuticals, Fort Worth, TX) was prepared at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in Tris buffer. Soluble human collagens (human collagen types I, III, IV, V and VI) were purchased from Sigma‐Aldrich. Fifty microlitres of NaOH solution (0·5 M) was added to 50 µl of each collagen solution to neutralise the pH. Hundred microlitres of the Clostridium collagenase/Tris solution was added to each of the collagen solutions and mixed. After mixing, the solutions were incubated at 37°C overnight; 100 µl of 1 mg/ml ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution was added at the end of the incubation period to stop the degradation. The samples were centrifuged in Centricon filters [Pall, molecular weight (MW) cutoff 100 kDa] to remove undigested collagens and Clostridium collagenase enzyme from the test solutions. SDS–PAGE was used to analyse the degradation products. All five collagens, both with and without the collagenase treatment, were loaded onto the gels. Each gel also contained MW markers and the Clostridium collagenase enzyme. Collagen degradation by trypsin (1 mg/ml) treatment followed the same procedure as Clostridium collagenase.

Keratinocyte migration assay

Keratinocytes at various passages were plated on gold‐coated coverslips, according to the method originally described by Albrecht‐Buehler (31) and modified by Woodley et al. (32) using computer‐assisted analysis. Briefly, gold‐coated coverslips were prepared using 22‐mm round glass coverslips, hydrogen tetrachloroaurate III (14·5 mM) sodium carbonate (36·5 mM) and 0.1% formaldehyde solution. Neonatal human dermal keratinocytes (Cascade, OR) were cultured in serum‐free Medium 153 (Cascade) for 24 hours, and collected for use. A gold‐coated coverslip was placed at the bottom of each well of a 6‐well plate. Ten thousand keratinocytes in 2 ml of serum‐free Medium 153 was placed onto the top of each gold‐coated coverslip. The plate was left to incubate at 37°C for 2 hours to allow attachment. After incubation, cells were treated with selected concentrations of the various degraded human collagen solutions (test solutions). Samples used for control purposes included 1 mg/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF) as a positive control, and serum‐free Medium 153 as a negative control, no treatment (NT). Test solutions were tested at 1:100 and 1:1000 dilutions in serum‐free Medium 153. After the test solutions were added, the plate was incubated at 37°C for 20 hours. Following incubation, the plates were rinsed, and each gold‐coated coverslip containing cells was mounted onto a glass slide. Cells were imaged using dark‐field optics. Areas of tracks left in the gold by migration of cells were quantified and recorded using imaging software, MetaVue Imaging System (Universal Imaging Corporation, PA). Numbers were then averaged to obtain migration results in pixels for each treatment.

Fibroblast migration assay (QCM chemotaxis cell migration assay)

The quantitative cell migration assay was used to determine the effects of various chemoattractants on human fibroblast cell migration. The QCM (33) Chemotaxis 96‐well Cell Migration Assay Kit was obtained from Millipore (lot# pso1486548, Millipore, MA). Migration stimulating activity was assessed by the movement of fibroblasts through the pores of the upper chamber and onto the bottom of the polycarbonate membrane in response to a chemoattractant of interest that was loaded into the bottom feeder tray. Adult human dermal fibroblasts (Cascade) were placed in supplement‐free medium and incubated at 37°C. The fibroblasts remained serum starved for 18–24 hours, and were then detached, centrifuged, re‐suspended and used for testing. In the lower ‘feeder tray’ chamber of the provided 96‐well plate, 150 µl of each chemoattractant was added. The positive control (EGF) was used at a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Serum‐free fibroblast Medium 106 (Cascade) was used as a negative control, NT. Each collagen degradation product was tested at a dilution of 1:100 in serum‐free fibroblast Medium 106. The fibroblast cell suspension (100 µl at 2·5–7·5 × 105cells/ml) was added into each well of the ‘migration chamber’, upper insert of the plate, which went on top of the ‘feeder tray.’ The plate was covered and incubated at 37°C for 18 hours. One hundred and fifty microlitres of the provided Cell Detachment solution was added into a new ‘feeder tray’. The ‘migration plate’ was then removed from the old ‘feeder tray’, and inverted over the sink to remove the serum‐free Medium 106. The ‘migration plate’ was placed into the new ‘feeder tray’ containing Cell Detachment solution, and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Once incubation was complete, 50 µl of provided dye/lysis solution was added into the ‘feeder tray’. The tray was incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature, 150 µl of solution from each well was transferred to a microplate well. Readings were taken on a plate reader at 520 nm. The digests of collagen I, III and IV were tested for this chemotactic migration of human dermal fibroblasts.

STATISTICS

Keratinocyte migration data for each treatment were averaged from a group of eight samples (n = 8). Multiple readings were also performed for each sample. Data between the treated and NT were statistically compared using Mann–Whitney rank sum test. To determine statistical significance, P< 0·05 was the decision level. Fibroblast migration test was in triplicates (n = 3). A t‐test (α = 0 · 05 with 4 degrees of freedom) was used to determine the statistical difference between the treated and NT. The decision level for statistical significance is P < 0·05.

RESULTS

Proteolytic effect of Clostridium collagenase on human collagens

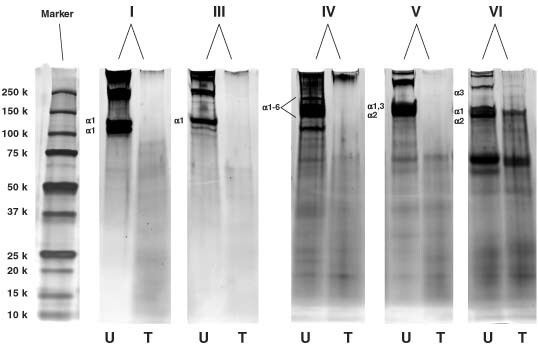

The proteolytic effect of Clostridium collagenase on the digestion of human collagen types I, III, IV, V and VI was examined by SDS–PAGE. Figure 1 illustrates the degradation results by presenting the treated and untreated collagen side‐by‐side. Collagenase‐treated type I, III, IV and V collagens displayed complete degradation of all α chains. Low MW degradation products were found at a lower MW range. Type VI showed limited degradation, whereas, after treatment, the bands for α1 and α2 chains were still visible, and an α3 band did not completely disappear. The protein band for Clostridium collagenase could be found in the collagenase lane. However, it was not seen in the lanes for the treated samples because of the filtration with Centricon filters.

Figure 1.

SDS–PAGE showing the degradation of human collagen types I, III, IV, V and VI (U: untreated; T: treated with Clostridium collagenase).

Keratinocyte migration

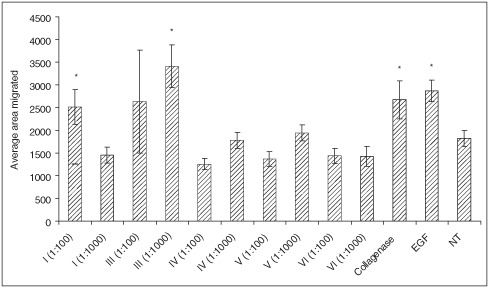

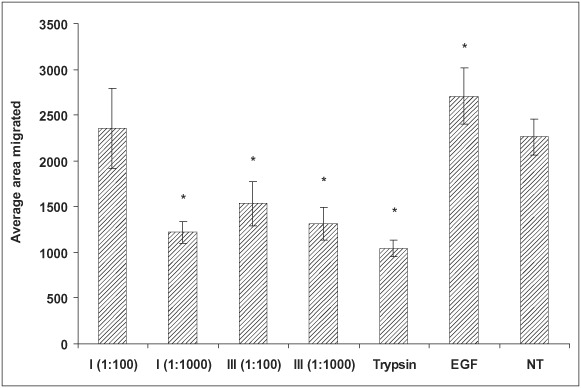

The degradation products from all tested collagen types were used to treat human keratinocytes to study their effect on cell migration (Figure 2). Two concentrations were used for each collagen type; EGF and the Clostridium collagenase enzyme were also incorporated as the controls. The untreated cells showed an average migration track of 1825 pixels, whereas the cells treated with EGF showed an average migration track of 2864 pixels. Cells treated with the degradation products from type IV, V and VI collagens did not show any increase in cell migration at either concentration. Cells treated with the degradation products from type I collagen at a high concentration (1:100) displayed increased migration (average 2516 pixels), while the lower concentration (1:1000) had no effect. The degradation products from the treated type III collagen significantly promoted keratinocyte migration at both 1:100 (2629 pixels) and 1:1000 (3407 pixels) concentrations. In addition, Clostridium collagenase at 5 µg/ml showed enhancement of cell migration. A control experiment was also conducted using trypsin‐treated collagen types I and III in keratinocyte migration. Figure 3 shows the migration results with trypsin‐treated collagen degradation products. It was noted that trypsin‐treated collagen degradation products did not show any promotion of cell migration. In addition, trypsin caused significant inhibition to cell migration.

Figure 2.

Effect of collagen digests produced by Clostridium collagenase on human keratinocytes migrating on a gold‐coated surface. Collagenase concentration was 5 µg/ml and epidermal growth factor (EGF) at 1 mg/ml was the positive control (*P< 0·05). NT, no treatment.

Figure 3.

Effect of collagen (types I and III) digests produced by trypsin (1 mg/ml) on human keratinocytes migrating on a gold‐coated surface (*P< 0·05). NT, no treatment.

Fibroblast migration

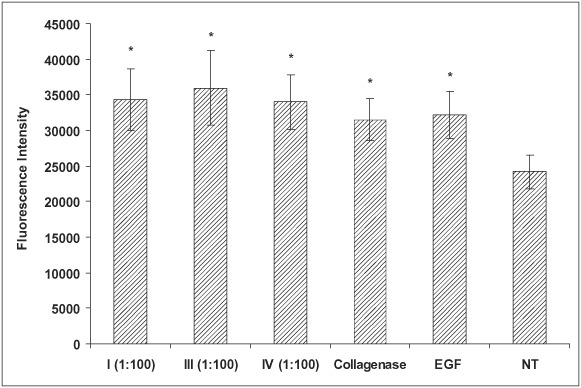

The degradation products from collagen types I, III and IV were used to examine the human fibroblast cell migration (Figure 4). EGF and the Clostridium collagenase enzyme used to treat the collagens were included as the controls. In the fibroblasts, all three collagen degradation products showed increased cell migration compared with the non treated control. Clostridium collagenase by itself showed some enhanced migration activity, but not as great as the collagen degradation products. Unlike the migration of keratinocytes, the degradation products from type IV collagen showed enhanced fibroblast migration.

Figure 4.

Effect of collagen (types I, III and IV) digests produced by Clostridium collagenase on human fibroblast migration. Fibroblast migration to the underside of the membrane was quantified by cell detachment and fluorescent staining, which was detected using the microplate reader. Collagenase concentration was 5 µg/ml and epidermal growth factor (EGF) at 1 mg/ml was the positive control (*P< 0·05). NT, no treatment.

DISCUSSION

Clostridium collagenase has been reported to contain both class I and class II collagenase enzymes, according to their specificity on the substrates (34). These collagenases are distinguished by their ability to digest native triple‐helical collagens (such as types I, II and III) into small peptides 1, 35. French et al. found that the class I and II collagenase enzymes initially attack these collagens at distinct sites, whose sequences have also been identified 1, 36. It has also been found that these two classes of collagenase enzymes are complementary in the patterns of attack on these collagens. Clostridium collagenase can also digest non triple‐helical collagens. For instance, type IV collagens are quite flexible triple helices that assemble into networks restricted to basement membranes (22). Karakiulakis et al. has found that collagenase from C. histolyticum can degrade type IV collagen with a high affinity of binding to this collagen (37). Type V collagen is also a fibril‐forming collagen (22); associating with type I and III collagens to form abundant fibrillar structures in most connective tissues (25). Degradation of type V collagen by Clostridium collagenase has not been reported. The results from the present study have confirmed the collagenolytic activity of Clostridium collagenase on collagen types I, III and IV. In addition, it has been further proven that Clostridium collagenase can effectively degrade type V collagen. At meantime, the data also indicate that Clostridium collagenase is not able to digest type VI collagen. Type VI collagen is a microfibrillar collagen aggregate‐to‐filament network in all connective tissues 30, 38. It is composed of three different polypeptide chains: α1(VI), α2(VI) and α3(VI), each of which has a short triple helix and large globular domains at both ends 39, 40. The α3(VI) chain exists as a different molecular structure. Its C‐terminal domain is 50% identical to that of the Kunitz structure of aprotinin‐type protease inhibitors (41), suggesting that type VI collagen may bear some inhibitory activity to resist protease degradation , especially for trypsin‐like serine proteases. We have also found in a separate study that other non collagenase proteases from the culture of C. histolyticum displayed activity to digest a chymotrypsin‐specific peptide substrate. Such proteolytic activity could be inhibited by aprotinin (data not provided in this article). From the results shown by gel electrophoresis (Figure 1), type VI collagen was degraded to some extent, but unlike the other collagens, the degradation was limited. This result can be explained by the inhibitory effect of the Kunitz structure on the α3(VI) chain. Overall, crude Clostridium collagenase contains a group of active enzymes that can effectively degrade most types of collagen in dermal and connective tissues.

It is very interesting that we observed that this bacterial collagenase has impact on in vitro cell movement. Herman (42) used Clostridium collagenase to treat ECM and found it could induce keratinocyte proliferation and migration. The experiment was conducted in two ways, so that keratinocytes migrated on Clostridium collagenase‐treated matrixes both in the absence or presence of Clostridium collagenase. Clostridium collagenase could stimulate keratinocyte migration by both the purified and the crude enzymes (42), while the purified enzyme had more pronounced migration effect than the crude enzymes. The cell migration data from our study confirmed the enhancement of keratinocyte migration by Clostridium collagenase. However, questions regarding why Clostridium collagenase affects cell migration have not been answered. It has been extensively discussed that the strictly regulated degradation and reorganisation of the ECM is required for the normal process of wound healing. Various proteolytic enzymes are needed for modulation of the wound matrix to facilitate the migration of keratinocytes and fibroblasts, and the subsequent wound closure 43, 44, 45, 46. For instance, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are found to be essential for keratinocytes to migrate on a collagen matrix. MMP‐1 (collagenase‐1) has been shown to cleave collagen, thereby providing a substrate that is more conducive to migration (43). Keratinocyte migration is also completely inhibited by anti‐collagenase‐1 antibodies, which can block the catalytic activity of the enzyme (43). Clearly, collagenase‐1 plays an important role in keratinocyte migration, most likely through the release of keratinocytes from the underlying basement membrane that is required for migration. If this is the case, collagenases are the only enzymes that are able to digest the collagen matrix to enable epithelial cells like keratinocytes to migrate. A similar situation was seen for MMP‐2 to promote epithelial cell migration on laminin‐5. Giannelli et al. reported that exogenous MMP‐2 induced the migration of breast epithelial cells on laminin‐5. It is known that MMP‐2 specifically cleaves the α2 subunit of laminin‐5 exposing a pro‐migratory site that triggers cell motility (47). The concept that cells focus proteolytic activities at their cell surface to help remove barriers to migration, or to promote detachment, becomes a possible mode of action. We have also conducted a controlled study using trypsin to examine keratinocyte migration (refer to Figure 3 for results). No evidence was found that trypsin could play a similar role in promoting cell migration. Further research is needed to find how the enzymes interact between the ECM and cell surface receptors (collagen‐binding integrins) promoting cell movement.

Our data also support Herman's finding that ECM treated with Clostridium collagenase leads to enhanced cell migration (42). In contrast to Herman's study, we used specific types of collagens, instead of ECM, which contain more than one protein. Our data showed that the collagen degradation products from different collagen types performed very differently. The degradation products from type I and III collagens promoted keratinocyte migration, while the other collagen types did not. By the proteolytic action of collagenase, collagens will be degraded into smaller peptides. These peptides bear the same segmental sequence of the original collagen molecules. The collagenolytic degradation molecules may regulate cellular functions, such as cell proliferation, adhesion and migration. Our data indicate that the breakdown products from types I and III have a significant impact on cell migration, suggesting that some peptides containing specific cell migration enhancing sequences are generated. Those sequences are related to the parent collagen molecule and the cleavage by Clostridium collagenase. The peptides generated by a non specific protease, trypsin, did not show the same effect as seen with Clostridium collagenase. For the first time we are able to report that these degradation products from type I and III collagens treated by Clostridium collagenase could significantly enhance cell migration; however at the present time, it is not clear what these peptides (sequences) are. Finding these peptides will be the next step in understanding this process.

In conclusion, the data presented in this article indicate that Clostridium collagenase is effective in digesting the major collagen types, suggesting that the enzyme can effectively degrade the collagenous component in necrotic tissues. In addition to debriding function, treatment with Clostridium collagenase is found to promote cell migration via two different mechanisms: by Clostridium collagenase itself and by the collagen degradation products. Collagens I and III treated with trypsin did not display any enhancing effect on keratinocyte migration.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors wish to thank Renée Carstens for technical writing contributions

REFERENCES

- 1. French MF, Bhown A, Van Wart HE. Limited proteolysis of types I, II and III collagens at hyper‐reactive sites by Clostridium histolyticum collagenase. Matrix Suppl 1992;1:134–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mallya SK, Mookhtiar KA, Van Wart HE. Accurate, quantitative assays for the hydrolysis of soluble type I, II, and III3H‐acetylated collagens by bacterial and tissue collagenases. Anal Biochem 1986;158:334–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grant NH, Alburn HE. Studies on the collagenases of Clostridium histolyticum. Arch Biochem Biophys 1959;82:245–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mandl I, Keller S, Manahan J. Multiplicity of Clostridium histolyticum collagenases. Biochemistry 1964;3:1737–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kono T. Purification and partial characterization of collagenolytic enzymes from Clostridium histolyticum. Biochemistry 1968;7:1106–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seglen PO. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol 1976;13:29–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Suggs W, Van WH, Sharefkin JB. Enzymatic harvesting of adult human saphenous vein endothelial cells: use of a chemically defined combination of two purified enzymes to attain viable cell yields equal to those attained by crude bacterial collagenase preparations. J Vasc Surg 1992;15:205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mandl I. Collagenase comes of age. In: Mandl I, editor. Collagenase. New York: Gordon & Breach, Science Publishers, 1972:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mandl I. Bacterial collagenases and their clinical applications. Arzneimittelforschung 1982;32: 1381–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vrabec R, Moserova J, Konickova Z, Behounkova E, Blaha J. Clinical experience with enzymatic debridement of burned skin with the use of collagenase. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol 1974;18:496–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hansbrough JF, Achauer B, Dawson J, Himel H, Luterman A, Slater H, Levenson S, Salzberg CA, Hansbrough WB, Dore C. Wound healing in partial‐thickness burn wounds treated with collagenase ointment versus silver sulfadiazine cream. J Burn Care Rehabil 1995;16(3 pt 1):241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Varma AO, Bugatch E, German F. Debridement of dermal ulcers with collagenase. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1973;136 :281–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barrett D Jr, Klibanski A. Collagenase debridement. Am J Nurs 1973;73:849–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee LK, Ambrus JL. Collagenase therapy for decubitus ulcers. Geriatrics 1975;30:91–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vetra H, Whittaker D. Hydrotherapy and topical collagenase for decubitus ulcers. Geriatrics 1975;30:53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rao DB, Sane PG, Georgiev EL. Collagenase in the treatment of dermal and decubitus ulcers. J Am Geriatr Soc 1975;23:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Altman MI, Goldstein L, Horowitz S. Collagenase: an adjunct to healing trophic ulcerations in the diabetic patient. J Am Podiatry Assoc 1978;68:11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boxer AM, Gottesman N, Bernstein H, Mandl I. Debridement of dermal ulcers and decubiti with collagenase. Geriatrics 1969;24:75–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zaruba F, Lettl A, Brozkova L, Skrdlantova H, Krs V. Collagenase in the treatment of ulcers in dermatology. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol 1974;18:499–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haimovici H, Strauch B. Use of collagenase in the management of stasis and ischemic ulcers of the lower extremities. In: Mandl I, editor. Collagenase. New York: Gordon & Breach, Science Publishers, 1972:177–83. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Soderhall C, Marenholz I, Kerscher T, Ruschendorf F, Esparza‐Gordillo J, Worm M, Gruber C, Mayr G, Albrecht M, Rohde K, Schulz H, Wahn U, Hubner N, Lee YA. Variants in a novel epidermal collagen gene (COL29A1) are associated with atopic dermatitis. PLoS Biol 2007;5:e242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gelse K, Poschl E, Aigner T. Collagens–structure, function, and biosynthesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2003;55:1531–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu T, Zhang J. Detection of V, III and I type collagens of dermal tissues in skin lesions of patients with systemic sclerosis and its implication. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 2008;28:599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fleischmajer R, MacDonald ED, Perlish JS, Burgeson RE, Fisher LW. Dermal collagen fibrils are hybrids of type I and type III collagen molecules. J Struct Biol 1990;105:162–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chanut‐Delalande H, Bonod‐Bidaud C, Cogne S, Malbouyres M, Ramirez F, Fichard A, Ruggiero F. Development of a functional skin matrix requires deposition of collagen V heterotrimers. Mol Cell Biol 2004;24:6049–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou J, Ding M, Zhao Z, Reeders ST. Complete primary structure of the sixth chain of human basement membrane collagen, alpha 6(IV). Isolation of the cDNAs for alpha 6(IV) and comparison with five other type IV collagen chains. J Biol Chem 1994;269:13193–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hudson BG, Reeders ST, Tryggvason K. Type IV collagen: structure, gene organization, and role in human diseases. Molecular basis of Goodpasture and Alport syndromes and diffuse leiomyomatosis. J Biol Chem 1993;268:26033–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Trueb B, Winterhalter KH. Type VI collagen is composed of a 200 kd subunit and two 140 kd subunits. EMBO J 1986;5:2815–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Trueb B, Schreier T, Bruckner P, Winterhalter KH. Type VI collagen represents a major fraction of connective tissue collagens. Eur J Biochem 1987;166:699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keene DR, Engvall E, Glanville RW. Ultrastructure of type VI collagen in human skin and cartilage suggests an anchoring function for this filamentous network. J Cell Biol 1988;107:1995–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Albrecht‐Buehler G. The phagokinetic tracks of 3T3 cells. Cell 1977;11:395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Woodley DT, Bachmann PM, O’Keefe EJ. Laminin inhibits human keratinocyte migration. J Cell Physiol 1988;136:140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gildea JJ, Harding MA, Gulding KM, Theodorescu D. Transmembrane motility assay of transiently transfected cells by fluorescent cell counting and luciferase measurement. Biotechniques 2000;29:81–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yoshida E, Noda H. Isolation and characterization of collagenases I and II from Clostridium histolyticum. Biochim Biophys Acta 1965;105:562–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. French MF, Mookhtiar KA, Van Wart HE. Limited proteolysis of type I collagen at hyperreactive sites by class I and II Clostridium histolyticum collagenases: complementary digestion patterns. Biochemistry 1987;26:681–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. French MF, Bhown A, Van Wart HE. Identification of Clostridium histolyticum collagenase hyperreactive sites in type I, II, and III collagens: lack of correlation with local triple helical stability. J Protein Chem 1992;11:83–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Karakiulakis G, Papadimitriu E, Missirlis E, Maragoudakis ME. Effect of divalent metal ions on collagenase from Clostridium histolyticum. Biochem Int 1991;24:397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Von Der MH, Aumailley M, Wick G, Fleischmajer R, Timpl R. Immunochemistry, genuine size and tissue localization of collagen VI. Eur J Biochem 1984;142:493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weil D, Mattei MG, Passage E, N’Guyen VC, Pribula‐Conway D, Mann K, Deutzmann R, Timpl R, Chu ML. Cloning and chromosomal localization of human genes encoding the three chains of type VI collagen. Am J Hum Genet 1988;42:435–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chu ML, Mann K, Deutzmann R, Pribula‐Conway D, Hsu‐Chen CC, Bernard MP, Timpl R. Characterization of three constituent chains of collagen type VI by peptide sequences and cDNA clones. Eur J Biochem 1987;168:309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chu ML, Zhang RZ, Pan TC, Stokes D, Conway D, Kuo HJ, Glanville R, Mayer U, Mann K, Deutzmann R. Mosaic structure of globular domains in the human type VI collagen alpha 3 chain: similarity to von Willebrand factor, fibronectin, actin, salivary proteins and aprotinin type protease inhibitors. EMBO J 1990;9:385–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Herman I. Stimulation of human keratinocyte migration and proliferation in vitro: insights into the cellular responses to injury and wound healing. Wounds 1996;8:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pilcher BK, Dumin JA, Sudbeck BD, Krane SM, Welgus HG, Parks WC. The activity of collagenase‐1 is required for keratinocyte migration on a type I collagen matrix. J Cell Biol 1997;137:1445–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pilcher BK, Sudbeck BD, Dumin JA, Welgus HG, Parks WC. Collagenase‐1 and collagen in epidermal repair. Arch Dermatol Res 1998;290 (Suppl):S37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Murphy G, Gavrilovic J. Proteolysis and cell migration: creating a path? Curr Opin Cell Biol 1999;11:614–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Steffensen B, Hakkinen L, Larjava H. Proteolytic events of wound‐healing–coordinated interactions among matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), integrins, and extracellular matrix molecules. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2001;12:373–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Giannelli G, Falk‐Marzillier J, Schiraldi O, Stetler‐Stevenson WG, Quaranta V. Induction of cell migration by matrix metalloprotease‐2 cleavage of laminin‐5. Science 1997;277:225–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]