Abstract

Pressure ulcers (PU) in patients with hip fracture remain a problem. Incidence of between 8·8% and 55% have been reported. There are few studies focusing on the specific patient‐, surgery‐ and care‐related risk indicators in this group. The aims of the study were

-

•

to investigate prevalence and incidence of PU upon arrival and at discharge from hospital and to identify potential intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors for development of PU in patients admitted for hip fracture surgery.

-

•

to illuminate potential differences in patient logistics, surgery, PU prevalence and incidence and care between Northern and Southern Europe. Consecutive patients with hip fracture in six countries, Sweden, Finland, UK (North) and Spain, Italy and Portugal (South), were included. The patients were followed from Accident and Emergency Department and until discharge or 7 days. Prevalence, PU at discharge and incidence were investigated, and intrinsic and extrinsic risk indicators, including waiting time for surgery and duration of surgery were recorded. Of the 635 patients, 10% had PU upon arrival and 22% at discharge (26% North and 16% South). The majority of ulcers were grade 1 and none was grade 4. Cervical fractures were more common in the North and trochanteric in the South. Waiting time for surgery and duration of surgery were significantly longer in the South. Traction was more common in the South and perioperative warming in the North. Risk factors of statistical significance correlated to PU at discharge were age ≥71 (P = 0·020), dehydration (P = 0·005), moist skin (P = 0·004) and total Braden score (P = 0·050) as well as subscores for friction (P = 0·020), nutrition (P = 0·020) and sensory perception (P = 0·040). Comorbid conditions of statistical significance for development of PU were diabetes (P = 0·005) and pulmonary disease (P = 0·006). Waiting time for surgery, duration of surgery, warming or non warming perioperatively, type of anaesthesia, traction and type of fracture were not significantly correlated with development of PU.

Keywords: Comorbidity, Dehydration, Hip fracture, Moist skin, North and South Europe, Old age, Braden scale, Pressure ulcers, Risk factors, Surgery

Introduction

It is anticipated that the expected increase in the size of the elderly population of Europe will result in a significant increase in the numbers of patients hospitalised for hip fractures (1). In fact, during the past 20 years, the number of hip fractures in patients ≥80 years has doubled (2).

Pressure ulcers (PU) is a frequent complication to hip fractures, and incidence of between 8·8% and 55% has been reported 3, 4. Versluysen (1985) (5) reported that 17% of patients admitted for hip fracture surgery had PU upon arrival and that 34% developed lesions during the first week in hospital. The largest number of PU in this study occurred on the day of surgery. In another study by the same author (6), 66% of the patients with hip fracture developed PU, the majority of them appeared during the first 48 hours after admission. Pressure ulcers can develop at any time during a care episode 7, 8, but the majority of surgery‐related PU are reported to appear within 2–4 days post‐surgery 9, 10. Most PU are avoidable (11), but not all (12).

Pressure ulcers have a major impact on quality of life and on the cost of hospital care (13). Patients with PU report ‘endless pain’, restricted activities and impact on their family lives (14). Patients with p. u. require significantly more nursing time, remain hospitalised for longer periods of time, generate higher hospital charges and require more health care resources after discharge than comparable patients without PU 15, 16, 17, 18, 19. It has been reported that patients developing a PU spend an average of 33 days longer at a rehabilitation ward compared with patients without such ulcers (20). Another consequence of PU is death. In one study (21), a 35% 3‐month mortality for patients with PU was reported. Reduction in health‐related quality of life because of PU has also been reported 22, 23. There are a few studies attempting to identify specific risk factors for development of PU after hip fracture surgery. Some are retrospective 3, 24 and some prospective (4, 9, 25, 26). A retrospective review of medical records of hip fracture patients at 20 hospitals in the United states of America between 1983 and 1993 showed that wait for surgery, intensive unit stay, longer surgical procedure and general anaesthesia were significant risk factors for PU (3). However, since the nineties, awareness of PU risks and quality of preventive care has improved. General anaesthesia is now more uncommon in hip fracture surgery, and operation tables are usually well padded to avoid development of PU. Few patients are admitted to intensive care unit after hip fracture surgery.

There is an increasing consensus that PU are a sign of acute illness and that particular intrinsic and extrinsic factors affect the tolerance of skin to pressure. They may contribute to loss of mobility or conspire to exacerbate the effects (27). Bliss (1992) (28) maintains that healthy people, including those with reduced mobility, do not normally develop PU, but that those same patients may become acutely vulnerable following the onset of an intercurrent illness or trauma.

Intrinsic risk factors (factors inherent in individual patients) include old age 3, 4, 9, 29, incontinence (30), malnutrition 31, 32, reduced food intake, female gender, ASA‐status and NYHA status (29) and anaemia (33) reducing oxygen delivery to tissue which may already be ischaemic (34). Incontinence and moisture might predispose for PU caused by shearing trauma. The moist skin causes the body to adhere to the mattress, thus increasing shearing forces (35). Friction is also exacerbated by the presence of moisture 35, 36. Excessive skin moisture, particularly incontinence has thus been reported to be one risk factor for PU development 37, 38. Moisture lesions have recently been discussed to be distinguished from PU (39). Dry skin, on the other hand, also increases the risk for injury because the elasticity of the skin is decreased (40). The effect of dehydration on tissue viability has been discussed by Livesley (1990) (34). General comorbidity (41) diastolic blood pressure ≤60 mm (42) and confusion (25) have also been reported to be significant risk factors for PU in patients with hip fracture.

Multiple pathologies

The aetiology of PU, therefore, appears to be multifactorial and often a result of multiple pathologies. This might explain the strong relationship noted already between old age and the formation of PU (27).

Versluysen (1986) (6) found that 91of 100 patients who were admitted with an expected diagnosis of fractured neck of femur shared a total of 315 separate diagnoses of concurrent illnesses of different body systems.

Extrinsic risk factors include shearing forces (43) and friction (43). Intensive care (3) and hypothermia (26) have also been reported to contribute to development of PU in hip fracture patients.

Time‐related risk factors reported for surgical patients are long waiting time before surgery (3, 33, 44) and length of surgery (9). Surgery per se (29) and length of surgery ≥4 hours (45) have been reported to be significant risk factors for PU development. A direct association between length of surgery and PU was not confirmed by Kemp et al. (46). The potential effects of shorter surgery have not been studied.

Risk assessment instruments

Prediction of potential complications to surgery in order to avoid them is an important quality indicator. The possibility to predict PU should have positive consequences both for the individual at risk and for the society.

There are several risk assessment instruments for PU available, but none is specifically designed for patients undergoing surgery 47, 48. The Braden risk assessment instrument has been proven to have a high reliability and validity (49) and to be the most reliable of those reported in the literature (50), even if its predictive value has been disputed in patients in intensive care, and when used by non trained staff (51). In one study, where medical record abstraction was performed in 545 patients with hip fracture, risk assessment was reported to be under‐utilised, inaccurate and unrelated to PU development in hip fracture patients (24). Recent studies by Houwing et al. (2004) (9) and Schoonhoven et al. (2002) (45) have also disputed the value of risk assessment tools for prediction of PU for any patient. One critical point that has been launched is the absence of simultaneous recordings of preventive actions taken (52). It can be hypothesised, however, that a validated risk assessment tool like the widely used Braden scale assists in identifying patients at some risk of developing PU during a care episode related to hip fracture surgery.

The aims of the present European, prospective cohort study were

-

•

to investigate prevalence and incidence of PU upon arrival and at discharge from hospital, and to identify potential intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors for PU development in patients admitted for hip fracture surgery.

-

•

to illuminate potential differences in PU prevalence, patient logistics and care of potential importance for PU between Northern and Southern Europe.

Patients and methods

The study was designed as a prospective cohort study with inclusion of 20 consecutive patients with a radiologically verified diagnosis of cervical or trochanteric hip fracture per centre. Each country had an experienced study coordinator who was a trustee member of the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) and who was responsible for the selection of centres and education of the local investigators and staff.

Study protocol

The study protocol agreed upon was designed in three main sections. Section A was aimed at collecting patient‐ and care‐related data at the Accident and Emergency (A&E) Department. Section B comprised questions related to perioperative care and in section C data regarding postoperative care were recorded.

The patients were followed up until discharge or for 7 days, whichever was shorter.

The patients’ skin was daily inspected in specified locations (occiput, scapulae, hips, sacrum, ischium, elbows, heels, back of calves and thighs and ankles) and documented on an anatomical drawing. Classification of PU was standardised and a ‘pressure ulcer card’ with colour pictures guiding the investigators to the correct classification.

Inclusion

One study coordinator (trustee of EPUAP) per country selected Departments of Orthopaedic Surgery willing to participate in the study.

Consecutive patients with radiologically verified cervical or trochanteric hip fractures who after verbal and written information gave their consent to participate were included. In cases where the patient was confused, consent was given by their next of kin.

Exclusion

Patients with multitrauma were excluded from the study.

Definition

A PU was defined as damage to skin and underlying tissues caused by pressure, shear or friction, or a combination of these factors (53).

Pressure ulcer prevalence was defined as PU upon arrival. Pressure ulcers ‘at discharge’ included patients with PU present upon arrival and persisting throughout the care episode as well as PU developed during the care episode (n = 37) and persisting until discharge. Pressure ulcer incidence represents only PU that developed during the care episode and were present at discharge and excludes PU prevalent upon arrival.

Classification of PU

The ulcers classified into four grades according to the EPUAP (53) classification guide.

-

•

Grade 1, Non blanching erythema of intact skin.

-

•

Grade 2, Partial‐thickness skin loss involving epidermis, dermis or both.

-

•

Grade 3, Full‐thickness skin loss involving damage to or necrosis of subcutaneous tissue that may extend down to but not through underlying fascia.

-

•

Grade 4, Full‐thickness skin loss with extensive destruction, tissue necrosis or damage to muscle, bone or supporting structures.

Sweden, Finland, United Kingdom is abbreviated to North and Spain, Italy, Portugal is abbreviated to South.

Risk assessment

The Braden risk assessment instrument was used. The instrument was translated and re‐translated into the local languages. The Braden scale consists of six domains, which are valued and given specific subscores, which are summarised to one total score.

Risk assessment according to the Braden scale was performed within the first few hours after arrival to the A&E. A cut‐off score of 16 was used (51). Maximum score is 23 (healthy persons).

Patient‐related variables

Intrinsic factors not included in the Braden instrument are documented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Other intrinsic factors documented

| Sex and age |

| Body mass index |

| Hunger, thirst and dehydration |

| Comorbidity |

| Haemoglobin |

| Blood pressure |

| Skin condition |

The condition of the skin of all patients arriving at the A&E was inspected for signs of moisture and PU during the first two post‐admittance hours. All body locations with particular attention to bony prominences were inspected according to a graphic figure displaying anatomical front and back projections.

Extrinsic/logistic factors recorded were as follows:

-

•

Site of the accident,

-

•

Time between arrival to A&E and surgery (hours),

-

•

Thickness of trolley mattresses at A&E,

-

•

Traction,

-

•

Type of anaesthesia,

-

•

Duration of surgery (hours) and

-

•

Intraoperative warming

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the help of SPSS (SPSS, Kista, Sweden) using group statistics, independent samples test, chi‐square, t‐test, Mann–Whitney U‐test, Wilcoxon, Z‐test, asym. sig. (two‐tailed), exact sig. (one‐tailed) and cross tab.

Results

Demographic data

The number of patients included were n = 635. The number of patients included per country are itemised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Included patients (n) and PU prevalence upon arrival and at discharge per country

| n | Prevalence (%) | Discharge (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| North | |||

| Finland | 300 | 7 | 26 |

| Sweden | 107 | 13 | 21 |

| Great Britain | 61 | 10 | 18 |

| Total | 468 | 26 | |

| South | |||

| Portugal | 24 | 4 | 4 |

| Italy | 41 | 0 | 16 |

| Spain | 104 | 12 | 16 |

| Total | 16 | ||

Prevalence of PU upon arrival

Sixty‐one patients of 599 (10%) had PU upon admittance to A&E [47/441 (10·4%) in North and 14/158 (8·9%)] in South. Fifty‐two PU (87%) were grade 1 ulcers, seven were grade 2 and two were grade 3. There was no grade 4 PU upon arrival to A&E. The most frequent locations were sacrum, heels and ischium.

Pressure ulcers at discharge and incidence

The PU of 21 patients who had PU documented upon arrival healed during the care episode, nine (43%) healed during the first day.

The number of patients with PU at discharge was 131/609 (22%). Pressure ulcers at discharge were more common in patients in the North (26%) than in the South (17%) (P = 0·058). Because 37 patients with PU upon admittance did not heal during the care episode, the incidence was 16% (97/614). Most ulcers were grade 1, and there was no grade 4 PU at discharge. Patient inclusion per country and PU prevalence upon arrival and at discharge are shown in Table 2.

Sex and age

| Sex | % |

|---|---|

| Male | 25 |

| Female | 75 |

Pressure ulcers at discharge were equally common in men (21%) and women (22%).

The median age of the patients was 80 years (range 37–99 years). In patients ≤70 years (n = 93), 12 (12%) had PU at discharge. Of patients ≥71 years (n = 499), 121 patients (23%) had PU at discharge (P = ·002).

Incidence of PU in relation to age was 8% for patients ≤70 years (n = 93) and 19% for patients ≥71 years(P < ·000).

Of the 37 patients with PU both upon arrival and at discharge, the median age was 83 years.

Types of fractures versus incidence of PU

Cervical fractures were more frequent (n = 353/550) than trochanteric (n = 197/550) (P = ·051). Cervical fractures were more common in the North (65%) than in the South (41%). Not specified (n = 52).

There was a weak correlation between cervical (P = ·433) and trochanteric (P = ·054) fractures and PU. Patients with trochanteric fractures had a slightly higher age (mean 81 years, median 82 years) than patients with cervical fractures (mean 78 years, median 80 years).

Site of fall accident

Eighty per cent of the patients had fallen and fractured their hips indoors both in the North and in the South.

Inspection routines for PU at A&E (n = 476)

In the North 1% and in the South 8% of the patients were routinely assessed for PU upon arrival prior to the study.

Pain upon arrival

Pain was routinely assessed upon arrival to A&E in 69% of the patients in the North and 33% of the patients in the South (P = 0·000) prior to the study.

Pain was reported by 473/568 patients (83%). Pain intensity upon arrival was registered in 406 patients (VAS 1–10, mean value 5·3, median 6).

There was no statistically significant correlation between pain upon arrival and PU incidence (P = 0·579) (Pearson’s chi‐square).

Smoking versus PU at discharge

Seventy‐seven of the patients were smokers. Eighteen of the smokers (23%) had PU at discharge. There was no significant correlation between smoking and PU at discharge (P = 0·762) or incidence of PU (P = 0·866).

Blood pressure

There was no significant correlation between systolic blood pressure ≤100 mmHg upon arrival (P = 0·220) or low diastolic blood pressure (<80 mmHg) upon arrival and PU at discharge (P = 0·205). In 50 patients with diastolic blood pressure ≤60 mmHg, 7 had PU (P = 0·694).

Haemoglobin (Hb)

One hundred and ninety‐nine patients had a Hb ≤10 g/dl. There was no statistical correlation between Hb ≤10 g/dl and PU incidence (P = 0·150).

Hunger, thirst and dehydration upon arrival

One hundred and fourteen patients of 611 (40%) were hungry upon arrival

Dehydration upon arrival (dry lips, thirst and skinfold test) was significantly more common in North (85%) compared with South (15%) (P = 0·000) and significantly correlated to PU at discharge (P = 0·005). Thirst and dehydration was not statistically correlated to PU incidence (P = 0·493 and P = 0·216), but of the 37 patients with PU at discharge, 47% were dehydrated upon arrival (P = 0·005). Symptoms at A&E and symptoms related to PU at discharge are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Symptoms at Accident and Emergency Department (any symptom, n = 337) and symptoms versus pressure ulcers (PU) at discharge (n = 134) Pearson’s chi‐square test

| Symptom % | Total n (%) | North n % | South n % | P value North/South | Versus PU P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hunger | 114/611 (40) | 88/443 (18*) | 26/168 (33) | 0·214 | 0·410 |

| Thirst | 283/606 | 241/445 | 42/161 | 0·000 | 0·577 |

| Dehydration | 144/616 | 123/454 | 21/162 | 0·000 | 0·005 |

Body mass index (n = 471)

The body mass index (BMI) had both mean and median of 24 (range 14–47). For the 37 patients with PU both upon arrival and at discharge, the mean was 22·21 (median = 22·56). A higher percentage of patients who were underweight (30%) compared with patients with a normal weight (24%) or overweight (19%) had a PU at discharge. There was no statistical correlation between low or high BMI and PU at discharge (P = 0·142) (Table 4) or between BMI and incidence of PU (P = 0·981).

Table 4.

Body mass index (BMI) (n = 471)

| BMI | North (%) | South (%) | Total (%) | P value North/South | P value versus PU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤20 | 19 | 15 | 18 | 0·058 | 0·142 |

| 21–24 | 38 | 30 | 36 | ||

| ≥25 | 43 | 55 | 46 |

Comorbid conditions (n = 452, diabetes n = 537)

Spain reported diabetes as the only comorbid condition.

Thus, concomitant diseases were reported in a cohort of 452 patients and diabetes in 537 patients. Cardiovascular disease was more common in South (Spain no report), 32/61 (52%) compared with North, 90/391 (23%). Diabetes was more frequently reported by the South, 19/146 (13%) compared with the North, 17/391 (4%). Cardiovascular disease was most frequently (78%) correlated to PU at discharge in Sweden (P = 0·00) and United Kingdom (UK) (P = 0·02) (few observations). Diabetes was significantly correlated to PU at discharge (P = 0·005). Comorbid conditions versus PU at discharge are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comorbid conditions versus pressure ulcers (PU) at discharge

| Disease/abnormal values | Total n (%) | P value versus PU | Incidence (P) | PU arr + disch (n = 37) n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | 59/624 | 0·085 | 0·232 | 6 |

| Cardiovascular | 323/605 (78) | 0·168 | 0·044 | 17 |

| Diabetes 1 and 2 | 90/609 (30) | 0·005 | 0·053 | 10 |

| Urological | 54/605 (13) | 0·697 | 0·561 | 3 |

| Malignancy | 52/606 (16) | 0·101 | 0·156 | 4 |

| Pulmonary | 83/601 (24) | 0·083 | 0·006 | 6 |

Braden risk assessment score compared with PU at discharge and with incidence of PU

Risk assessment was routinely performed prior to the study in 34% in the South and 13% in the North.

There was a significant correlation between a low Braden score (≤16) and PU at discharge (P = 0·05) (Mann–Whitney U‐test). When the activity variable was removed, the P value was P = 0·04. There were major inconsistencies in the filling in of the activity and mobility variables. In many cases, the pre‐fracture status was marked. The significance of total Braden score versus PU incidence when activity and mobility variables were excluded was P = 0·036.

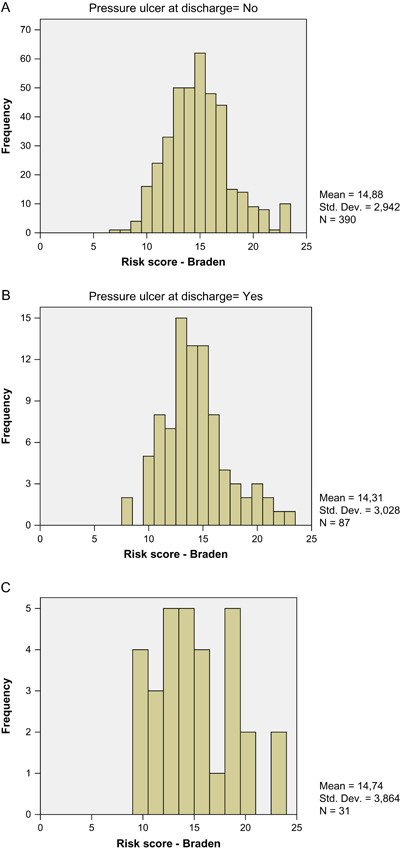

Braden risk subscores and PU are shown in Table 6 and Figure 1A–C).

Table 6.

Braden risk subscores versus patients with pressure ulcers (PU) at discharge (n = 131) and versus incidence (n = 97)

| Braden subscore | Braden subscore versus PU at discharge (n = 131), P value | Braden subscores versus incidence of PU (n = 97), P value |

|---|---|---|

| Activity | 0·14 | 0·217 |

| Mobility | 0·21 | 0·704 |

| Moist skin | 0·00 | 0·004 |

| Friction | 0·02 | 0·031 |

| Nutrition | 0·02 | 0·069 |

| Sensory perception | 0·04 | 0·019 |

Figure 1.

(A) Braden scores for patients without pressure ulcers (PU) at discharge. (B) Braden scores for patients with PU at discharge. (C) Braden scores for patients without PU at arrival but at discharge (n = 31), six values missing.

Care‐related factors

Trolleys and thickness of mattresses at A&E Department

Ninety‐five per cent of the patients in the North and 80% in the South were placed on a trolley upon arrival. The thickness of mattresses ranged between a mean of 6 cm (Italy) and a mean of 10 cm (Portugal).

There was no significant correlation between thickness of A&E trolley mattress and PU at discharge (P = 0·14).

Time between arrival and start of surgery

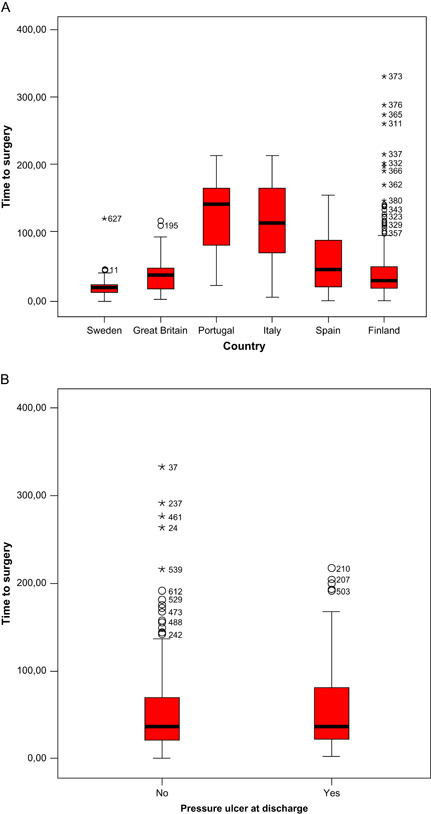

Waiting time for surgery had a mean of 55 hours and median of 37 hours (range 58 minutes to 333 hours). In the North, the median time was 48 hours and in the South 90 hours. There was no significant correlation between waiting time to surgery and PU at discharge (P = 0·335) in the total population. Time to surgery for the respective country is shown in Figure 2A and time to surgery and PU at discharge in Figure 2B. The incidence of PU in the hospital with the shortest waiting time (mean 16 hours) versus the incidence in the hospital with the longest waiting time (mean 153 hours) differed slightly, but was not statistically significant (P = 0·075).

Figure 2.

Time between arrival to Accident and Emergency (A&E) Department and start of surgery, all countries. (B) Time between admission to A&E and start of surgery versus patients without pressure ulcers (PU) (no) and with PU (yes) at discharge.

Traction (n = 591)

Traction was used in 6% of the patients in the North and in 74% in the South. The use of traction and PU at discharge or incidence of PU was P = 0·501 and P = 0·511.

Anaesthesia (n = 593)

Spinal anaesthesia was used for 89% of the patients in the North and for 86% in the South. There was no significant correlation between type of anaesthesia and PU at discharge or incidence of PU (P = 0·964, P = 1·000).

Perioperative warming (n = 402)

Warming of operation table and/or warmed infusion was used in a total of 191/402 patients (48%), 62% in the North and 4% in the South. There was no significant correlation between warming and PU at discharge (P = 0·536) or incidence of PU (P = 0·891).

Duration of surgery (n = 587)

Duration of surgery had a mean of 80 minutes and median of 74 minutes. Statistically shorter duration was reported in the North (mean 74 minutes, median 65 minutes), compared with the South (mean = 97 minutes, median 90 minutes) (P < 0·000). Duration of surgery for cervical fractures had a mean of 100 minutes (median 79 minutes) with hip replacement, and without hip replacement it was 72 minutes (median 60 minutes). For trochanteric fractures with hip replacement, mean time for surgery was 95 minutes (median 90 minutes). There was no significant correlation between duration of surgery and PU at discharge (P = 0·845) or incidence of PU (P = 0·804). There was no significant correlation between hip replacement or not and PU at discharge (P = 0·817).

For patients with surgical procedures lasting ≥120 minutes, 85/575 (15%) had PU. The relationship between lengthy surgery and PU incidence was not significant (P = 0·433).

Postoperative turning schedule

A turning schedule was planned for 19% of the patients in the North and for 52% in the South (P = 0·000). The majority of the patients with a turning schedule were turned every second hour.

Three hundred and twenty‐eight of 483 patients had no turning schedule (68%). Twenty‐three per cent without turning schedule and 24% with turning schedule had PU at discharge (P = 0·85).

Lack of turning schedule in relation to the incidence of PU was not significant (P = 0·486).

Discussion

Methodological considerations

This study is, to our knowledge, the largest prospective study of a cohort of hip fracture patients in Europe. Although a considerable number of investigators have been involved, which might be hazardous to the validity of the study, it was managed in each country by skilled investigators and trustees of EPUAP. One weakness is the uneven number of patients included in the respective country, which was explained by local conditions. Even if the results for these reasons may be interpreted with caution, some general findings of statistical significance were noted.

The patients were followed throughout the hospital episode or until day 7 post‐surgery, and the skin was observed for PU upon arrival and daily until discharge. The number of patients with PU doubled during the hospital stay. Thirty‐seven of the patients admitted with PU had them throughout the care episode. The prevalence of PU upon arrival was 10% compared with 18% reported in a smaller Swedish study of similar design (4). Also the incidence was lower, 16% compared with 55–29% 4, 54, which might partly be explained by the shorter follow up time in the present study. However, most surgery‐related PU have been reported to develop between admission and the fourth day post‐surgery (4), an observation also described by other authors 9, 10. The low incidence is most likely, however, explained by a general improvement of care with a focus on PU prevention since the previous studies. This is, however, not reflected in the pre‐study routines for skin inspection in A&E, which was only performed in 1% in the North and in 8% in the South. The higher prevalence and higher number of PU at discharge and the higher incidence in the North is surprising, especially because patients in the South had significantly longer waiting time to surgery, longer duration of surgery, more trochanteric fractures and more commonly were treated by traction. There were also more diabetic patients in the South. Unlike a previously reported study (29), there was no gender difference in development of PU. Reduced tissue tolerance is believed to explain the development of PU to some degree. Tissue tolerance is an individual response to external trauma and decreases in old age. Therefore, increasing age makes the tissue more vulnerable to pressure. This can be explained by the decrease of elastin in soft tissue and changes in collagen synthesis resulting in decreased mechanical capacity of the tissue. Elderly people also have less subcutaneous tissue; their muscles lose their tone and the regeneration of skin cells is slower (35). Hoshowsky and Schramm (1994) (55) found the risk of developing a PU after surgery tripled in people ≥70 years and older. In the present study, age ≥71 years was significantly associated with PU at discharge (P = 0·002).

The majority of patients both in Northern and Southern Europe had fallen and fractured their hips indoors. Cervical fractures were more common than trochanteric (P = 0·051), especially in the North. Pressure ulcers were more common in patients with trochanteric fractures (P = 0·054), which is probably explained by the higher mean age in this group of patients. It has been hypothesised that pain contributes to development of PU by immobilising the patient and by reducing the capillary flow in the skin. Pain was reported by 83% of the patients upon admittance, but was, however, not significantly associated with PU development. Routine assessment of pain upon arrival was more than twice as common a procedure in the North (69%) than in the South (33%). There was no statistically significant correlation between the patients smoking habits, low diastolic or systolic blood pressure and development of PU. Berlowitz and Wilking (1989) (56) and Bergstrom and Braden (1992) (42) reported an association between the development of PU and a decrease in nutritional intake. One fourth of the patients in the present study reported hunger upon arrival, but there was no significant correlation between hunger and PU at discharge. Dehydration, diagnosed by thirst, dry mouth and skinfold was a significant risk factor (P = 0·005) for PU development. Significantly more patients in the North (P = 0·000) compared with the South were thirsty and dehydrated upon arrival, which might be one explanation of the higher incidence of PU in the North. This hypothesis may also be strengthened by the fact that patients in the North were undergoing surgery significantly earlier than those in the South, giving the South patients more time to adjust to normal hydration before surgery. In this study, unlike the Bergstrom and Braden (1992) (42) study, neither a low nor a high BMI was significantly associated with increased risk of PU development, even if underweight patients more commonly had PU. In the group of patients with persisting PU (n = 37), the BMI was lower, but still within the normal interval. Low Braden nutrition subscore was not statistically significant for PU incidence in this study, but was so for PU at discharge (P = 0·02).

Diseases that have been reported to be associated with an increased risk for PU development are pulmonary diseases, anaemia, diabetes mellitus, spine injury and vascular disease 35, 55, 57, 58. Diabetes was in the present study, a significant risk factor for development of PU (P = 0·005). Pulmonary disease (P = 0·006) and cardiovascular disease (P = 0·044) were also risk factors for PU incidence.

Risk assessment was almost three times more frequently undertaken in the South than in the North (34% versus 13%) prior to the study. Both the total Braden risk assessment score (P = 0·05) and the majority of the subscores were significantly associated with PU development. There seems to have been discussions about the registration of mobility and activity in the Braden scale because in some cases, the pre‐fracture status of the patient was documented and not the present status. This led us to calculate both the total Braden score and the Braden score without activity and mobility subscores. The strongest subscore correlation was found between moist skin and PU development. Moist skin can be because of perspiration and/or incontinence; the latter factor has been well documented to be a risk factor for PU development (35, 36). Moist skin causes the body to adhere to the mattress, thus increasing shearing forces. Defloor et al. (2005) (39) debates whether skin lesions caused by moisture should be called PU or moisture lesions because these ulcers are not caused by ischaemia but by softening of the skin by moisture.

Care‐related factors were of minor importance for development of PU in this study, and thus, traction, thickness of trolley mattresses, time to surgery and duration of surgery, spinal anaesthesia or perioperative warming did not show any significant correlation with PU at discharge. In previous studies, prolonged operations have been shown to be a significant risk factor for PU development (59). However, hip fracture surgery is a fast procedure nowadays (median 74 minutes), and very few patients have had surgery, which has lasted more than 2 hours.

Hypothermia has been reported to be a potential risk factor for PU development, and perioperative warming has, in one study in hip fracture patients, been showed to reduce the risk of PU (26). Perioperative warming, however, increases the oxygen demand of the tissue and might in fact increase the risk of PU. In surgery ≥10 hours, Grous et al. (1997) (59) found that the use of warming blankets was the only significant risk factor for PU development. In the present study, no such correlation was shown; in fact, in Southern countries where perioperative warming was rare, PU at discharge were less frequent.

Waiting time to surgery has been reported to influence the development of PU. Because the waiting time till surgery was significantly longer in the South, this might have been a significant risk factor but, in fact, fewer patients in the South had PU than those in the North, and there was no statistical significance of long waiting time for development of PU (P = 0·335). However, the hospital with the shortest waiting time had fewer PU than the hospital with the longest waiting time (P = 0·075), indicating that in a bigger study, waiting time might be of significant importance. It might also be so that the hospital with short waiting time has been particularly dedicated to reduce also other risks. In one study from that hospital, waiting time to surgery for hip fracture patients was systematically and substantially shortened, which reduced the number of patients with PU at discharge from 19% in 1998 to 4·5% in 2000 (60). In that study, the number of patients who got pain relief within 1 hour post‐admittance was also doubled during the study period 1998–2000.

Low general prevalence of PU in the South has been reported by other authors (61) and confirmed in the present prospective study.

Preoperative risk assessment was not frequently a routine neither in the South or in the North and its value has been disputed (45). However, bearing in mind the findings of the present study, PU in hip fracture patients can be accurately predicted using the Braden scale, especially if the activity and mobility subscores are removed or clarified. It should be recognised, however, that risk calculators were never designed to replace clinical judgement but rather to assist in decisions, which channel resources appropriately (27). Even if the validation of PU risk assessment scales remains a topic of considerable debate and uncertainty, and bearing in mind the recommendation that they should be evaluated in combination with preventive measures (52), it is likely that they contribute to increased awareness of some risk factors, which, if not observed, can lead to development of avoidable PU.

Recommendations included the following:

-

•

Risk assessment and skin observation should be performed upon arrival to the A&E and daily until discharge with special attention to patients aged ≥71 years.

-

•

Pay particular attention to significant Braden risk factors such as moist skin, friction, malnutrition and low sensory perception.

-

•

Observe and correct dehydration.

-

•

Observe patients with diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases who might be at risk of developing PU.

Acknowledgements

Gerry Bennet in memoriam who contributed to the design of the study and undertook supervision of the study in the UK. Christoffer Labuc for his excellent data support. All local monitors at each hospital involved in the study; Anita Söderqvist, Sweden, Heli Kallio, Nina Kuni, Päivi Mäntyvaara, Marja Niskasaari, Finland, Eila Ricci, Marco Masina, Italy, Katia Furtado, Portugal, Montserrat Arboix, Justo Rueda Lopez, Spain for excellent data collection. The study was funded by the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) and the Johanniterorden, Sweden.

This study was approved by local Ethics committees where appropriate and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

References

- 1. Melton LJ III. Hip fractures: a worldwide problem today and tomorrow. Bone 1993;14 Suppl 1:S1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thorngren KG. Fractures in older persons. Disabil Rehabil 1994;16:119–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baumgarten M, Margolis D, Berlin JA, Strom BL, Garino J, Kagan SH, Kavesh W, Carson JL. Risk factors for pressure ulcers among elderly hip fracture patients. Wound Repair Regen 2003;11:96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gunningberg L, Lindholm C, Carlsson M, Sjoden PO. The development of pressure ulcers in patients with hip fractures: inadequate nursing documentation is still a problem. J Adv Nurs 2000;31:1155–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Versluysen M. Pressure sores in elderly patients. The epidemiology related to hip operations. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1985;67:10–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Versluysen M. How elderly patients with femoral fracture develop pressure sores in hospital. BMJ 1986;292:1311–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Land L. A review of pressure damage prevention strategies. J Adv Nurs 1995;22:329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mullineaux J. Cutting the delay reduces the risk. Assessment of the risk of developing pressure sores among elderly patients in A&E. Prof Nurse 1993;9:22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Houwing R, Rozendaal M, Wouters‐Wesseling W, Buskens E, Keller P, Haalboom J. Pressure ulcer risk in hip fracture patients. Acta Orthop 2004;75:390–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. VanWijck F. Decubitus langs de meetlat (Pressure ulcers along the measuring rod). Medisch Nieuws 1998;6:37. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cullum N, Deeks JJ, Fletcher AW, Sheldon TA, Song F. Preventing and treating pressure sores. Qual Health Care 1995;4:289–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thomas DR. Are all pressure ulcers avoidable? J Am Med Dir Assoc 2003;4(2 Suppl):S43–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rochon PA, Minaker KL. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research guidelines for pressure ulcer prevention: improving practice and a stimulus for research. J Gerontol 1993;48:M3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hopkins A, Dealey C, Bale S, Defloor T, Worboys F. Patient stories of living with a pressure ulcer. J Adv Nurs 2006;56:345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Allman RM. Pressure ulcers among the elderly. N Engl J Med 1989;320:850–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Allman RM, Damiano AM, Strauss MJ. Pressure ulcer status and post‐discharge health care resource utilization among older adults with activity limitations. Adv Wound Care 1996;9:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Allman RM, Goode PS, Burst N, Bartolucci AA, Thomas DR. Pressure ulcers, hospital complications. disease severity: impact on hospital costs and length of stay. Adv Wound Care 1999;12:22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. De Lisa J. Compounding the challenge for PM&R in the 1990’s. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1985;66:792–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kiel DP, Eichorn A, Intrator O, Silliman RA, Mor V. The outcomes of patients newly admitted to nursing homes after hip fracture. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1281–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Indig R, Ronen R, Eldar R, Tamir A, Susak Z. Pressure sores: impact on rehabilitation following surgically treated hip fractures. Int J Rehabil Res 1995;18:54–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lindholm C, Bergsten A, Berglund E. Chronic wounds and nursing care. J Wound Care 1999;8:5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Franks PJ, Winterberg H, Moffatt CJ. Health‐related quality of life and pressure ulceration assessment in patients treated in the community. Wound Repair Regen 2002;10:133–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tidermark J, Zethraeus N, Svensson O, Tornkvist H, Ponzer S. Quality of life related to fracture displacement among elderly patients with femoral neck fractures treated with internal fixation. 2002. Journal of Orthopeadic Trauma 2003;17(8 Suppl):S17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stotts NA, Deosaransingh K, Roll FJ, Newman J. Underutilization of pressure ulcer risk assessment in hip fracture patients. Adv Wound Care 1998;11:32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gunningberg L, Lindholm C, Carlsson M, Sjoden PO. Implementation of risk assessment and classification of pressure ulcers as quality indicators for patients with hip fractures. J Clin Nurs 1999;8:396–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scott EM, Leaper DJ, Clark M, Kelly PJ. Effects of warming therapy on pressure ulcers – a randomized trial. AORN J 2001;73:921–7,929–33,936–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Edwards M. The rationale for the use of risk calculators in pressure sore prevention, and the evidence of the reliability and validity of published scales. J Adv Nurs 1994;20:288–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bliss MR Acute pressure area care: Sir James Paget’s legacy. Lancet 1992;339:221–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lindgren M, Unosson M, Krantz AM, Ek AC. Pressure ulcer risk factors in patients undergoing surgery. J Adv Nurs 2005;50:605–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Horn SD, Bender SA, Ferguson ML, Smout RJ, Bergstrom N, Taler G, Cook AS, Sharkey SS, Voss AC. The National Pressure Ulcer Long‐Term Care Study: pressure ulcer development in long‐term care residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52:359–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ek A, Unosson M, Larsson J, Von Schenk H, Bjurulf P. The development of pressure sores related to nutritional state. Clin Nutr 1991;10:245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mathus‐Vliegen EM. Old age, malnutrition, and pressure sores: an ill‐fated alliance. J Gerontol 2004;59:355–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gunningberg L, Lindholm C, Carlsson M, Sjoden PO. Effect of visco‐elastic foam mattresses on the development of pressure ulcers in patients with hip fractures. J Wound Care 2000;9:455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Livesley B. Prevention of pressure sores. The Lancet 1990;335:1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Defloor T, Grypdonck MH. Sitting posture and prevention of pressure ulcers. Appl Nurs Res 1999;12:136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dealey C. Managing pressure sore prevention. Salisbury: Quay Books, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Goldstone LA, Goldstone J. The Norton score: an early warning of pressure sores? J Adv Nurs 1982;7:419–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Norton D. Research and the problem of pressure sores. Nurs Mirror Midwives J 1975;140:65–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Defloor T, Schoonhoven L, Fletcher J, Furtado K, Heyman H, Lubbers M, Witherow A, Bale S, Bellingeri A, Cherry G, Clark M, Colin D, Dassen T, Dealey C, Gulasci L, Haalboom J, Halfens R, Hietanen H, Lindholm C, Moore Z, Romanelli M, Soriano JV. Statement of the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel‐Pressure Ulcer Classification: differentiation between pressure ulcers and moisture lesions. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2005;32:302–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. AHCPR . Pressure ulcers in adults: prediction and prevention. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Margolis DJ, Knauss J, Bilker W, Baumgarten M. Medical conditions as risk factors for pressure ulcers in an outpatient setting. Age Ageing 2003;32:259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bergstrom N, Braden B. A prospective study of pressure sore risk among institutionalized elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:747–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Versluysen M. Pressure sores: causes and prevention. Nursing (Lond) 1986;3:216–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Grimes JP, Gregory PM, Noveck H, Butler MS, Carson JL. The effects of time‐to‐surgery on mortality and morbidity in patients following hip fracture. Am J Med 2002;112:702–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schoonhoven L, Defloor T, Van Der Tweel I, Buskens E, Grypdonck MH. Risk indicators for pressure ulcers during surgery. Appl Nurs Res 2002;15:163–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kemp MG, Keithley JK, Smith DW, Morreale B. Factors that contribute to pressure sores in surgical patients. Res Nurs Health 1990;13:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Flanagan M. Who is at risk of a pressure sore? A practical review of risk assessment systems. Prof Nurse 1995;10:305–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. MacDonald K. The reliability of pressure sore risk‐assessment tools. Prof Nurse 1995;11:169–70, 172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bergquist S Subscales, subscores, or summative score: evaluating the contribution of Braden Scale items for predicting pressure ulcer risk in older adults receiving home health care. J Wound, Ostomy Continence Nurs 2001;28:279–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bridel J. Assessing the risk of pressure sores. Nurs Stand 1993;7:32–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bergstrom N, Braden BJ, Laguzza A, Holman V. The Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk. Nurs Res 1987;36:205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Defloor T, Grypdonck MF. Validation of pressure ulcer risk assessment scales: a critique. J Adv Nurs 2004;48:613–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. EPUAP . Pressure Ulcer Treatment Guidelines. EPUAP, Oxford, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gunningberg L, Lindholm C, Carlsson M, Sjoden PO. Reduced incidence of pressure ulcers in patients with hip fractures: a 2‐year follow‐up of quality indicators. Int J Qual Health Care 2001;13:399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hoshowsky VM, Schramm CA. Intraoperative pressure sore prevention: an analysis of bedding materials. Res Nurs Health 1994;17:333–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Berlowitz DR, Wilking SV. Risk factors for pressure sores. A comparison of cross‐sectional and cohort‐derived data. J Am Geriatr Soc 1989;37:1043–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gendron F. “Burns” occurring during lengthy surgical procedures. J Clin Eng 1980;5:19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Papantonio CT, Wallop JM, Kolodner KB. Sacral ulcers following cardiac surgery: incidence and risks. Adv Wound Care 1994;7:24–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grous CA, Reilly NJ, Gift AG. Skin integrity in patients undergoing prolonged operations. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 1997;24:86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hommel A, Ulander K, Thorngren KG. Improvements in pain relief, handling time and pressure ulcers through internal audits of hip fracture patients. Scand J Caring Sci 2003;17:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Clark M, Bours G, Defloor T. The prevalence of pressure ulcers in Europe. EPUAP Review 2002. http://www.eupap.org [Google Scholar]