Abstract

The majority of burn victims do not need to be treated in a burn centre. Adequate care can be given by non specialised medical personnel, provided that proper guidelines are followed. The article outlines and reviews these guidelines.

Keywords: Burn disease, Burn wound, Burn wound management, General burn care

Introduction

Although no reliable statistics are available about burn patients outside burn centres, it is likely that burns are among the most common types of trauma occurring in any society. Most burns are relatively small and consequently not life threatening, but large burns, even partial thickness ones, still pose a major threat when not treated properly.

Even smaller burns may cause major morbidity, because the injury is very painful and may lead to disfiguring scar formatting, primarily hypertrophic scarring (1).

This article provides a basic overview of burn care, particularly aimed at the non specialised hospital and the non specialised health care worker.

Types of burns

Burns (thermal) injuries can be categorised as follows:

-

•

Scalds: the injury is caused by contact with a hot fluid (i.e. hot tea, soup and coffee). In most cases, these injuries, when cooled quickly, are partial thickness.

-

•

Flame: the injury is caused by exposure to flames (i.e. a house fire or a barbecue explosion with clothing catching fire). These burns are usually full thickness.

-

•

Flash: the injury is caused by very short exposure to a burning gas or vapour (i.e. a barbecue explosion without clothing catching fire). The injury is usually partial thickness.

-

•

A contact burn: the injury is caused by contact with a hot surface. In many cases, these burns are not deep. However, particularly the combination of pressure and prolonged exposure to the heat source may lead to major injuries, as is the case in patients who, after a seizure, remain in contact with a hot surface for a prolonged period (2, 3). Similarly, burns caused by contact with molten metals, hot coals or other high‐temperature agents are usually very deep.

-

•

Electrical burns are, in fact, thermal injuries. This type of burn is caused by contact with or strike through of an electrical current: the electricity is converted to heat which causes coagulation and cell walls to explode. The amount of heat is in direct proportion to the amperage and electrical resistance of the tissues through which the electricity passes (4) and may lead to extensive and deep tissue necrosis. This, in turn, may lead to acidosis or myoglobinuria, which are life‐threatening complications. Thus, early exploratory surgery is necessary. Sometimes, the extent of the injury may not be immediately apparent, particularly when most of the damage done is on the subcutaneous or deeper levels.

-

•

Radiation: the injury is caused by exposure to heat radiation. The typical example of this type of burn is the sun burn. The injury is usually first degree.

Other types or injuries are commonly treated in burn centres but have a different aetiology:

-

•

Radiation burns as caused by radiotherapy are, in the opinion of the author, not real burns but ulcers, as this type of injury is not caused by thermal energy and will react differently to ‘standard’ therapy because of the radiation damage to the underlying tissues.

-

•

Chemical burns: as with therapeutic radiation, the mechanism of injury is different, but, again, because of the skin injury and possible consequence of the agent being absorbed through the skin, patients with chemical injuries usually end up in a burn centre (5).

-

•

Frostbite: when occurring over large surfaces, major tissue damage may be the result, requiring care similar to that provided to burn patient (6). Frostbite areas may very well need skin grafting.

-

•

Dermatological diseases such as Stevens Johnson syndrome, epidermolysis bullosa and toxic epidermal necrolysis 7, 8, 9, 10, 11): the results of these diseases may be major skin loss, thus leading to a level of morbidity that is similar to that of patients with major burns.

-

•

Other skin diseases accompanied by major skin loss, such as necrotising fasciitis (12, 13), and unusual infections such as phaeohyphomycosis (14).

This article primarily will discuss the treatment of true thermal injuries.

Depth of burns

The depth of a burn is very important as it determines how (surgically or not) the lesions should be treated.

The depth classification is related to the anatomy of the skin. The upper layer, the epidermis, is separated from the dermis, the underlying layer, by the basal membrane. The dermis contains epidermal structures such as the hair follicles, the sweat glands and sebaceous glands. If some of these structures are still intact, the epidermis can, in principle, heal spontaneously ‘from its deep roots’. If the epidermis and dermis are completely destroyed, as is the case in a full thickness lesion, reepithelialisation can only occur from the wound edges. This type of healing will take considerably longer, and in large burns, it will not be successful.

The thickness of the skin varies over the body: in very thin skin (the eyelids and the dorsum of the hand), a given heat insult will result in more damage than in very thick skin (i.e. the lower areas of the back). Consequently, a burn of the dorsum of the hand becomes deep more quickly than a burn of the lower back.

First degree

The typical first‐degree burn is the sun burn. The skin is painful, but there is no breach of the epidermis. The skin looks red and dry and there are no blisters.

Superficial partial thickness (superficial second degree)

In this type of burn, the epidermis is destroyed, thus exposing the underlying more superficial parts of the dermis. Blisters may or may not occur. The skin (underneath the blisters) is moist, pink in colour and hypersensitive to the touch (Figure 1). Blanching with pressure is positive, and capillary refill is virtually immediate.

Figure 1.

Typical partial thickness burn.

Deep partial thickness (deep second degree)

Here, the superficial parts of the dermis also have been destroyed, thus exposing the deep dermis. The exact depth of this type of burn may be very difficult to determine, as it may mimic a superficial one (with pain, pink surface, etc.), but it may also look like a full thickness one (see below). Capillary refill is slow or may not occur at all.

Full thickness burns (Third degree)

In this type of burn, the entire epidermis and dermis are destroyed. Initially, these burns are not or hardly painful (the nerve endings, residing in the dermis, have been destroyed as well). The aspect depends on the mode of injury and may be anywhere from white (a deep scald) to dark grey or black (a flame burn). The wound surface is usually dry and leather like to the touch (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Typical full thickness burn.

Fourth‐degree burns

In fourth‐degree burns, the entire skin is destroyed, and substantial thermal damage also has been done to subcutaneous and deeper tissues (i.e. muscle).

Depth diagnosis

Establishing a correct depth diagnosis is largely based on the patient history (e.g., having been in a car fire virtually always results in a full thickness burn) as well as on judging the physical aspects of the burn. The pin prick tests may be helpful to determine the pain level: the burn is very gently touched with the sharp tip of a needle, and the patient is asked about the level of pain that is experienced. The level of blanching of the skin may also help establishing a proper depth diagnosis.

Dyes have been used in the past, particularly in experimental burns, in an attempt to distinguish between dead and vital tissues, but are not used in the clinical situation. Fluorescein has been tested quite extensively (15), based on the same principles but, again, is not used clinically. Ultrasound has been used as well but was shown not to be better than clinical judgement with respect to determining burn depth (16).

Laser Doppler Flowmetry seems to be promising. In clinical research, the technique was proven to be reliable (17, 18). Recently, devices have become available that make the technique practical in the day‐to‐day setting, making accurate and rapid diagnoses over large surfaces possible within a short time frame 18, 19, 20, 21).

Physiology of a burn wound

Burns are dynamic wounds which means that overtime they may change, particularly with respect to their depth: this phenomenon is known as conversion or secondary deepening 22, 23, 24). Burns that were initially diagnosed as superficial partial thickness may actually turn out to be (or have become) deeper after a few days. While the physiological mechanisms of conversion are beyond the scope of this article, it is important to recognise that desiccation of the wound bed, as well as infection, may contribute to or lead to wound conversion. Consequently, the dressing choice in partial thickness burns plays an important role in the prevention of conversion (25).

However, in spite of the use of proper dressings and techniques, some burns may convert anyway. It also has been recognised that even experienced burn physicians and burn nurses sometimes misjudge the initial depth of a burn.

Size of the burn, inhalation injury and burn disease

Morbidity and mortality in burn care is largely defined by the size of the burn, the depth and whether or not an inhalation injury and/or other concomitant or pre‐existing diseases exist (26) (Table 1). Even superficial but very large burns, particularly in elderly and young children, are still associated with a high level of morbidity and mortality.

Table 1.

Severity of burns

| Minor burn |

| <15% TBSA in adults |

| <10% TBSA in children or elderly |

| <2% TBSA full thickness in children or adults without cosmetic or functional at risk areas |

| Moderate burn |

| 15–25% TBSA in adults, <10% full thickness |

| 10–20% TBSA partial thickness in children |

| <10 years and adults >40 years with <10% full thickness TBSA |

| <10% TBSA full thickness in children or adults without cosmetic or functional at risk areas |

| Major Burn |

| >25% TBSA |

| >20% TBSA in children <10 years and adults >40 years |

| >10% TBSA full thickness burns |

| All burns involving eyes, ears, face, hand, feet and/or perineum that are likely to result in functional or cosmetic impairment |

| All high‐voltage electrical burns |

| All burn injuries complicated by major other trauma and/or inhalation injury |

| All poor‐risk patients with a burn injury |

TBSA, total body surface area.

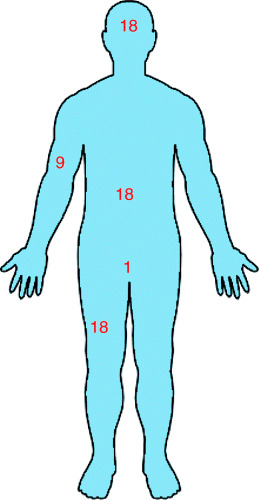

Burn size is expressed as a percentage of the total body surface area (TBSA) and may be determined by the rule of nines (27): the body is divided in areas of nine or multiples of nine percent. The head and arms each count for nine percent, each side of the trunk and each leg count for 18 percent, and the remaining one percent is reserved for the genitalia and the perineum (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Rule of nines.

For children, these percentages are different: for example, in a very young child the head counts for 18 percent. Burn centres use much more specific charts for determining the exact size of a burn.

The amount of necrotic tissue, heat and protein loss is directly related to the size of the burn injury and will cause major systemic problems in large burns. Because of these secondary effects of the skin injury, a large burn is much more than just a skin injury: the systemic effects cause the ‘burn disease’ which is associated with multiorgan responses.

The immediate threat of a larger burn is shock, due to a major change in capillary permeability which is associated with massive fluid transport out of the circulation into the interstitium.

Longer term complications are the risk of sepsis and organ system responses to shock and to the ‘burn toxins’ (28, 29) that are released from the coagulation necrosis of the skin.

A specific, very serious complication which quite often accompanies flame burns is inhalation injury, damage to the tracheal and pulmonary system caused by inhaling hot and/or toxic gasses and fumes (30). Often, this condition needs artificial ventilation. It is still associated with a high level of morbidity and mortality (31, 32).

Better management of these complications, in combination with better topical therapies and more aggressive surgical approaches, has led to a significantly lower mortality over the last decades, and, nowadays, survival of patients with full thickness burns of more that 95% TBSA is reported in the literature (33, 34).

First aid and guidelines for referral

Guidelines for referral are fairly straightforward (Table 2).

Table 2.

Indications for referral to a burn centre

| Patients with: |

| Partial thickness burns greater than 10% TBSA. |

| Full thickness burns |

| Burns that involve the face, hands, feet, genitalia, perineum and/or major joints |

| Chemical injuries |

| Electrical burn (including lightning injuries) |

| Any burn with concomitant trauma, where burn injury poses the greatest (acute) risk |

| Inhalation injuries |

| Pre‐existing medical conditions that could complicate management, prolong recovery or affect mortality |

| Furthermore: |

| The non presence of a hospital with qualified personnel and/or equipment for the care of critically burnt children. |

With respect to simple measures (i.e. cooling and cleaning of the wound, IV administration of fluids), initial care essentially is identical and independent of whether or not a patient is referred.

-

•

Dissipating the heat is the first objective as tissue temperatures above 45°C continue to cause local injury (35). Cooling with running tap water for 10 minutes is essential as this removes as much heat as possible, helps reducing the initial pain 36, 37, 38) and decreases oedema in the wound (39). Particularly in young children, the risk of under cooling, with associated dangerous drops in core temperature exists: thus, burn patients should not be emerged in a bath with ice cold water.

-

•

Rings on fingers and toes have to be removed: these will serve as a tourniquet when oedema starts to occur.

-

•

Wounds may be gently cleaned with a bland soap. Chlorhexidine gluconate soap is preferred by some because of its activity against regular skin flora (40).

-

•

Tar and asphalt burns should be cooled first. The causing agents will stick to the skin: physically peeling these materials off may do further harm to the skin and the wound. Thus, it is better to use a solvent (41).

-

•

Many chemical lesions may benefit from rinsing with water as well as this at least dilutes the agent. However, in many cases, more specific measures are necessary 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48). Therefore, it is always important to identify the chemical agent that caused the injury. Neutralising an alkaline burn with acid and vice‐versa should not be done: proper titration is impossible and the chemical reaction is exothermic, thus producing heat and, potentially, additional injury.

-

•

Prior to transportation, clothing may be removed, but this has to be done carefully as it may be stuck to the wound. A neutral dressing may be used to cover the burnt areas. Silver sulphadiazine should not be used if the patient is referred, as painful removal of the cream upon arrival in the burn centre will have to take place to assess wound aspect and size.

-

•

In larger burns, administration of IV fluids may be indicated prior to transporting the patient to a burn centre, if transportation is expected to take longer than 60 minutes. Ringers lactate should be infused at 2–4 ml/kg/percentage TBSA (49). IV lines should be introduced into larger veins (central lines are preferable) and, if possible, should not penetrate through burnt skin.

-

•

Narcotics may be used as pain medication but may only be given intravenously: other ways of administration should be avoided as the pattern of uptake is unpredictable.

-

•

If an inhalation injury is suspected, 100% humidified oxygen should be provided during transportation. However, given the possible acute onset of oedema, it is wise to consult with the burn centre to which the patient will be transported about possible intubation prior to putting the patient in the ambulance or helicopter.

-

•

Similarly, guidelines from a burn centre are advisable when one is considering escharotomies (50, 51): these are release excisions that may need to be made in patients with circumferential deep burns that may restrict respiratory excursion of the chest, circulation into the limbs and/or post‐burn intraabdominal hypertension (52).

Before transporting a patient to a burn centre, it is, in fact, always wise to call the centre about general and specific measures they would like to be taken before the patient is sent off.

Principles of wound management in burn care

Management of the burn wounds depends largely on the depth of the burn but should fulfil the following objectives: reduction of pain, prevention of infection, desiccation and conversion, rapid healing, and, for the long term, minimisation of the change of scarring problems, particularly hypertrophic scarring and contractures.

First‐degree burns

These burns do not require any dressings. A soothing, moisturising cream in combination with an anti‐inflammatory pain killer usually provides sufficient patient comfort.

Superficial partial thickness burns

These lesions potentially heal on their own within approximately 2 weeks, without the necessity of skin grafting and without significant scarring. An appropriate dressing should be used, particularly to reduce pain and to help prevent infection. It needs to be realised that superficial partial thickness may convert and becomes deeper (23, 24). Thus, even when the initial diagnosis established a superficial burn, healing times longer than 2 weeks are a reason to check for conversion: virtually always secondary tangential excision (see below) will be necessary.

Some advocate the use of collagenase to remove the thin layer of necrosis that exists in partial thickness burns, although this is not standard practice in most burn centres (53, 54).

Blister formation is very common in patients with superficial partial thickness burns. The literature is contradictory with respect to whether or not blister should be removed. Some state that the blister roof acts as a biological occlusive dressing and that blister fluid is beneficial to wound healing and has antimicrobial properties. Other research indicates the opposite, particularly with respect to the fluid being detrimental to fibroblasts (22, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65).

With the availability of synthetic occlusive dressings and realising that large blisters will probably break anyway, an option for small blister would be to carefully evacuate the fluid with a syringe after the blister roof has been painted with povidone iodine or chlorhexidine, and, after evacuation, to support the blister with a polyurethane film or thin hydrocolloid dressing. For large blisters that will probably break anyway, the blister and blister fluid may be removed and replaced with a synthetic occlusive or moisture retentive dressings.

Deep partial thickness burns

These wounds may heal spontaneously as well but, because fewer epithelial remnants are left in the wound, will take more time than superficial partial thickness burns. In fact, many deep partial thickness burns will take more than 2–3 weeks and consequently will result in significant scarring.

It is therefore that many burn centres are more aggressive with these types of burns and perform tangential excision 66, 67, 68). With this technique, using a specially designed dermatome, thin layers of necrosis are excised until a viable wound bed (as proven by punctate bleeding) is reached. Depending on the depth of the wound bed, subsequent grafting (for the deeper burns) may be performed, but the more superficial burns may be treated with a dressing: different centres take different approaches here.

When the depth of a burn is difficult to determine, tangential excision also is used as a diagnostic tool: again, the depth of the burn is judged from the wound bed left after excision.

Mixed partial thickness burns

In this type of burn, superficial and deeper areas cannot be easily distinguished or are confluent with each other in a mosaic‐like fashion. Again, tangential excision is used as a diagnostic tool, and deeper excised areas may be grafted while the superficial ones are left to heal spontaneously, with the help of an appropriate dressing.

Timing of the procedure depends on the burn centre but most will perform tangential excision within the first few days after the injury.

Full thickness burns

The preferential treatment for full thickness burns is excision and grafting, unless the lesions are so small that they can be expected to heal spontaneously within a few weeks. Enzymes that may replace surgical excision are being tested at the moment (69, 70) but are not the standard treatment at this moment.

Spontaneous desloughing will occur but will take considerable time and the wound may infect in the mean time, with sepsis as a possible consequence. If spontaneous debridement does occur, the resulting wound bed will certainly be contaminated and it is usually of poor quality: reepithelialisation may start but will not succeed over large, exposed surfaces. Contraction will also occur and will result in contractures: the edges of the wound will be drawn towards each other as a consequence of cellular changes in the wound bed as well as changes in the extracellular matrix. If this happens over a joint, flexing of the joint will occur, and the rigidity of the wound bed and its skin will prevent extension of the joint.

The lack of spontaneous healing and the scarring problems that result are the main reasons why excision is, in fact, the only real option for the treatment of full thickness burns, and it needs to occur as soon as possible (66, 71, 72). Early excision has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality significantly (73).

Excision will result in an open‐wound bed that needs to be covered as soon as possible. Preferentially, this needs to be done with autografts. Full sheet autografting offers the best results but, in major burns, is usually only reserved for cosmetically and functionally important areas such as the face, the neck and the hands, when not enough donor sites are available to cover all excised wounds with full sheets.

When large areas have been excised, alternative options are available. Among them, meshing the grafts is a good option. Different techniques are available, but they all use small incisions in the graft so that it can be expanded 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80): ratios of expansion depend on equipment used, personal preference of the surgeon and, again, the total amount of grafts available. Thorough fixation of the graft is necessary and can be done with staples or sutures, different types of synthetic glue (81), fibrin glue (82), specially designed fixation materials 83, 84, 85) and techniques (86). More recently, the use of a vacuum‐creating wound care device (87) has been advocated by some.

Cultured epithelium may also be used to cover excised areas. As soon as possible, biopsies are taken from undamaged skin of the burn victim. The different cell layers of the biopsy are separated and keratinocytes put in culture. After 10–14 days, cultured confluent sheets of the patients own epidermis are ready for application. Although this technique is not new (88, 89), several disadvantages (biochemical and physical fragility, odd aspects of the grafted areas, the lack of dermis and economical factors) still have to be overcome to make it widely used, although its life‐saving properties have been described as well 90, 91, 92, 93, 94).

An alternative technique depends on the use of temporary coverage materials: these are used to cover the wound until donor sites (see below) have healed and can be reused (reharvested) again which, depending on the depth and location of the donor site, the age of the patient and some other factors, may take anywhere from 7 days to 3 weeks.

A number of different temporary cover materials is available: the most common ones are allografts (cadaver skin from a skin bank, amnion membrane) 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105), xenografts [primarily porcine skin (106, 107), less commonly used nowadays] or (semi) synthetic materials. One of the semisynthetic materials is bilayered and designed in such a way that the wound bed grows into the wound side layer of the material: it thus becomes a ‘neodermis’108, 109, 110, 111). The outer layer of the dressing is a thin silicone sheet which protects the underlying material and wound from desiccation and infection. This sheet can be peeled of and replaced with autografts once the donor sites can be reharvested.

Donor sites

Donor sites, from which the skin grafts are taken, can be virtually anywhere in the body.

In big burns, the scalp is often used as the site reepithelialises rapidly (thus can be reharvested quickly and often) (112). Alopecia is usually not a problem because there are so many, deep‐seated, hair follicles.

Donor sites themselves can cause considerable morbidity, primarily because they are very painful 113, 114, 115, 116, 117). In large burns and, particularly, in elderly patients with frail skin, donor sites may also be difficult to heal (118).

Dressings for donor sites require the same set of properties as those for burns (see below). A major distinction, though, is that donor site may bleed heavily during the first hours to days after they have been made. Among haemostatic materials used to deal with this bleeding, pharmacological agents such as thrombin‐ and adrenaline‐soaked gauze bandages (119) are used, as well as special dressings such as alginates (120).

Dressing materials and techniques

Partial thickness burns, unless they are so deep that they have to be excised, can be managed well with dressings, and a plethora of different materials is available. For burns that will be excised within a short period after admission, it does not make a great deal of difference what type of preoperative material is used.

The most commonly used material for treating partial thickness burns is silver sulfadiazine 1% cream (121). This material has a reasonable antimicrobial profile, but it also has significant side effects such as the need for frequent dressing changes, pain associated with these dressing changes and discoloration of the wound bed [pseudo eschar (122)] which makes judging the wound difficult once the material has been applied a number of times 123, 124, 125, 126). Some contribute initial leucopoenia to the material, but others consider transient leucopoenia a normal consequence of the burn injury 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132).

Also, commonly used are different types of impregnated gauze. However, most of these materials adhere to the wound, and often tissue starts to grow into the gauze mesh, causing significant pain and damage to the wound bed upon dressing removal. Therefore, these materials should be avoided as dressing for burn care and wound care in general.

A large number of newer dressings have become available, most of them based on the principles of moist wound healing (116, 117, 133, 134, 135, 136) which prevents the wound from desiccation and prevents gauze‐type adherence and tissue ingrowth. Some modern gauze‐based dressings have been shown not to be adherent (137, 138) and, therefore, might be indicated as well. Most moisture retentive, non adherent dressings also help reducing pain (139).

In a simplified way, a number of dressing categories can be defined: synthetic materials, biological materials, biosynthetic materials and skin substitutes (for different materials different terminologies are used, which makes classification confusing).

The group of synthetic materials is by far the largest and includes hydrocolloids, foams, hydrofibres, alginates, film dressings, silicon‐based materials and many others (113, 120, 133, 140, 141). Some of these dressings have antimicrobial agents [nowadays primarily silver (115, 140)] incorporated in them.

The most appropriate dressing combines a number of properties. The material must

-

•

be able to handle large amounts of exudate

-

•

not be painful upon application or removal and help minimising pain in the period in between

-

•

be cost effective and easy to use

-

•

provide a moist wound environment

-

•

be an off the shelf, or otherwise readily available, product

-

•

have no (serious) side effects

-

•

not allow for tissue ingrowth

-

•

be antimicrobial, passively (by creating a moist wound environment) or actively (by having an active compound incorporated)

-

•

be non toxic

-

•

be non allergenic

With respect to dressings with an antimicrobial compound, the recently developed silver dressings are very promising as some of them combine the good antimicrobial properties of silver with good dressing properties of the material in which the silver is embedded (115, 140, 142, 143).

It is important to realise that many of ‘ideal dressing’ properties are claimed for many materials. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss properties and claims for all materials individually. However, claims made must have been proven in clinical trials and published in peer‐reviewed journals, and it is the task of the health care provider to base his/her decision on materials to be used on these articles, rather than on non substantiated claims or on just a series of case studies.

Along the same lines, it is also very important to realise that all materials within one group (i.e. all alginates, films, hydrocolloids and silver dressings) may actually not have the same properties. However, manufacturers quite often tend to extrapolate their claims from other materials in the same group. Thus, a critical approach is necessary.

Biological materials are usually either allografts or xenografts (100, 104, 105, 107) although other, non mammal‐derived (144) materials are being used as well. Xenografts [primarily porcine skin (106, 107)] are commercially available as are some forms of allografts.

Biological materials have in common that the skin structure of the graft acts as a biological occlusive dressing. These grafts usually become temporarily adherent to the wound bed, to be rejected or slough off over time.

They all tend to generate an immune response at some level although this depends on the species from which the graft is obtained and the way the graft is preserved.

Allografts are considered, by many, the theoretical gold standard for burn dressings, but for religious, commercial, economical and infrastructural reasons, their availability differs greatly from country to country. Theoretically, allografts (and xenografts) can transfer a donor disease to the graft recipient, but careful screening of the donor and the graft itself, as well as certain types of preservation (145), in practice reduce this risk to a virtually negligible level.

Biosynthetic materials combine a biological source (quite often collagen or other compounds of the extracellular matrix) with a synthetic matrix or top layer. These materials aim to use the advantages of a biological matrix, with or without the advantage of different top layers. Their in vivo performance largely depends on the purpose for which the material is designed and, consequently, the physical and biochemical structure of the compounds. Some perform well as temporary dressings while others are designed to be incorporated (al least partially) into the wound bed.

A number of skin substitutes are currently available or in the process of being developed. Many of them use a biological matrix (collagen and/or other molecules found in the extracellular matrix) which is seeded with live cells, such as fibroblast and/or keratinocytes 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152). The purpose of these materials is not only to provide a good dressing but also to bathe the wound in growth factors and other cytokines delivered into the wound milieu by the living cells in the dressing.

The possible advantage of this approach over ‘simply’ applying one or two growth factors from a delivery system is that the living cells are supposed to ‘sense’ what type of growth factor is needed in the wound, at what time and in which amounts.

Non living growth factor and cytokine delivery systems (i.e. a cream with one or two growth factors in it) do not play a major role in burn care and are beyond the scope of this article.

Long‐term results

After reepithelialisation is complete, the wound‐healing process continues into the remodelling phase. During this phase, deposited collagen is broken down and replaced with new and reorganised collagen. However, in many burns, the remodelling phase goes awry both with respect to the type of collagen and its orientation: macroscopically, this results in hypertrophic scarring. Hypertrophic scars are raised above the skin level and very inflamed in the beginning. They can be very debilitating and will interfere negatively with the quality of life, as they may limit movement, can be painful and virtually always are very pruritic. The psychological aspects of ‘being ugly’ are extremely important in this context as well.

Hypertrophic scarring is virtually certain to occur in burns that have taken a long time to heal spontaneously (153). However, also rapidly healing burns may result in serious scar formation, as scarring is largely genetically determined: dark‐skinned patients have a significantly higher risk of serious scarring (1, 154). Scarring also depends on other factors, such as the location of the wound (a sternotomy incision, e.g., virtually always results in a hypertrophic scar). During the reepithelialisation process, not much can be done to prevent hypertrophic scarring. However, because the change of hypertrophic scar formation is to a certain degree linked to the length of reepithelialisation, using dressings and techniques that are proven to reduce time to healing may contribute indirectly to reducing the incidence of hypertrophic scarring (153).

In patients who are prone to scarring (based on the results of previous injury and wound‐healing time), preventative measures may be taken after reepithelialisation is complete. These measures include the use of customised pressure garments 155, 156, 157, 158), with or without silicon sheeting as a contact layer on the wound 159, 160, 161). Corticosteroid injections are also used (162, 163), and other therapies are being developed as well, among them the use of different types of laser (164, 165) and, possibly, the use of pharmacological agents (166).

The results of hypertrophy prevention are often not truly satisfactory, and a visible scar may remain, although in the long time, hypertrophic scars will become flatter and less inflamed. However, surgical scar revision is often necessary, particularly when scar formation leads to contractures 167, 168, 169).

Keloid formation is different from hypertrophic scarring, both physiologically and macroscopically: a typical keloid extends beyond the borders of the original wound and has a cauliflower‐type aspect 170, 171, 172). Prevention and treatment of keloid are even more difficult than that of hypertrophic scarring 173, 174, 175, 176, 177) and lies beyond the scope of this article.

Conclusion

The treatment of large burns and burns in functional areas should be done in a burn centre. In these centres, an entire team (physicians, nurses, OTs, PTs dieticians, psychologists, etc.) is dedicated to burn care, and their treatment options often lead to impressive results.

However, the large majority of burn victims suffers from lesions that do not need this high level of care and that are small enough to be treated outside a burn centre, in a general hospital or an outpatient clinic, provided that wound management is done in line with burn care guidelines and modern wound care research.

This article attempts to give an overview of the principles of burn care, both for small and large burns. For the smaller ones, the principles of burn wound care (as opposed to burn disease care) should be used as a guideline. Because the number of materials, available for the treatment of partial thickness burns, is so extensive, it is the task of the physician and health care worker to become familiar with dressings that provide good burn care and to use evidence‐based medicine for the choice of dressings to be allowed into their clinics.

References

- 1. Rockwell WB, Cohen IK, Ehrlich HP. Keloids and hypertrophic scars: a comprehensive review[see comments]. Plast Reconstr Surg 1989;84(5): 827–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DeToledo JC, Lowe MR. Microwave oven injuries in patients with complex partial seizures. Epilepsy Behav 2004;5(5):772–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Josty IC, Mason WT, Dickson WA. Burn wound management in patients with epilepsy: adopting a multidisciplinary approach. J Wound Care 2002;11(1):31–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sances A Jr, Myklebust JB, Larson SJ, Darin JC, Swiontek T, Prieto T, Chilbert M, Cusick JF. Experimental electrical injury studies. J Trauma 1981;21(8):589–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sykes RA, Mani MM, Hiebert JM. Chemical burns: retrospective review. J Burn Care Rehabil 1986;7(4):343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pulla RJ, Pickard LJ, Carnett TS. Frostbite: an overview with case presentations. J Foot Ankle Surg 1994;33(1):53–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peters W, Zaidi J, Douglas L. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: a burn‐centre challenge. Cmaj 1991; 144(11):1477–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kelemen JJ III, Cioffi WG, McManus WF, Mason AD Jr, Pruitt BA Jr. Burn center care for patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Am Coll Surg 1995;180(3):273–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spies M, Vogt PM, Herndon DN. [Toxic epidermal necrolysis. A case for the burn intensive care unit]. Chirurg 2003;74(5):452–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGee T, Munster A. Toxic epidermal necrolysis syndrome: mortality rate reduced with early referral to regional burn center. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;102(4):1018–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yarbrough DR III. Treatment of toxic epidermal necrolysis in a burn center. J S C Med Assoc 1997;93(9):347–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Redman DP, Friedman B, Law E, Still JM. Experience with necrotizing fasciitis at a burn care center. South Med J 2003;96(9):868–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Barillo DJ, McManus AT, Cancio LC, Sofer A, Goodwin CW. Burn center management of necrotizing fasciitis. J Burn Care Rehabil 2003;24(3):127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arnoldo BD, Purdue GF, Tchorz K, Hunt JL. A case report of phaeohyphomycosis caused by cladophialophora bantiana treated in a burn unit. J Burn Care Rehabil 2005;26(3):285–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Black KS, Hewitt CW, Miller DM, Ramos E, Halloran J, Bressler V, Martinez SE, Achauer BM. Burn depth evaluation with fluorometry: is it really definitive? J Burn Care Rehabil 1986;7(4):313–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wachtel TL, Leopold GR, Frank HA, Frank DH. B‐mode ultrasonic echo determination of depth of thermal injury. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1986;12(6):432–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park DH, Hwang JW, Jang KS, Han DG, Ahn KY, Baik BS. Use of laser Doppler flowmetry for estimation of the depth of burns. Plast Reconstr Surg 1998;101(6):1516–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holland AJ, Martin HC, Cass DT. Laser Doppler imaging prediction of burn wound outcome in children. Burns 2002;28(1):11–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hemington‐Gorse SJ. A comparison of laser Doppler imaging with other measurement techniques to assess burn depth. J Wound Care 2005;14(4):151–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mileski WJ, Atiles L, Purdue G, Kagan R, Saffle JR, Herndon DN, Heimbach D, Luterman A, Yurt R, Goodwin C, Hunt JL. Serial measurements increase the accuracy of laser Doppler assessment of burn wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil 2003;24(4):187–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Riordan CL, McDonough M, Davidson JM, Corley R, Perlov C, Barton R, Guy J, Nanney LB. Noncontact laser Doppler imaging in burn depth analysis of the extremities. J Burn Care Rehabil 2003;24(4):177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saranto JR, Rubayi S, Zawacki BE. Blisters, cooling, antithromboxanes, and healing in experimental zone‐ of‐stasis burns. J Trauma 1983;23(10):927–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zawacki BE. The natural history of reversible burn injury. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1974;139(6):867–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zawacki BE. Reversal of capillary stasis and prevention of necrosis in burns. Ann Surg 1974;180(1): 98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hermans MHE. Treatment of burns with occlusive dressings: some pathophysiological and quality of life aspects. Burns 1992;18 Suppl 2: S15–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Herndon DN. Total Burn Care, 2nd edition. New York: Saunders, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lund CC, Browder NC. The estimate of area of burns. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1944;79: 352–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rosenthal SR. Burn toxin and its competitin. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1982;8(3):215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Allgower M, Stadtler K, Schoenenberger GA. Burn sepsis and burn toxin. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1974;55(5):226–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Enkhbaatar P, Traber DL. Pathophysiology of acute lung injury in combined burn and smoke inhalation injury. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;107(2): 137–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Smith DL, Cairns BA, Ramadan F, Dalston JS, Fakhry SM, Rutledge R, Meyer AA, Peterson HD. Effect of inhalation injury, burn size, and age on mortality: a study of 1447 consecutive burn patients. J Trauma 1994;37(4):655–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Barrow RE, Spies M, Barrow LN, Herndon DN. Influence of demographics and inhalation injury on burn mortality in children. Burns 2004;30(1):72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Herndon DN, Gore D, Cole M, Desai MH, Linares H, Abston S, Rutan T, Van Osten T, Barrow RE. Determinants of mortality in pediatric patients with greater than 70% full‐thickness total body surface area thermal injury treated by early total excision and grafting. J Trauma 1987;27(2):208–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Herndon DN, LeMaster J, Beard S, Bernstein N, Lewis SR, Rutan TC, Winkler JB, Cole M, Bjarnason D, Gore D. The quality of life after major thermal injury in children: an analysis of 12 survivors with greater than or equal to 80% total body, 70% third‐degree burns. J Trauma 1986;26(7):609–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moritz ARH, Henriquez FC. Studies of thermal injury. The relative importance of time and surface area in the causation of cutaneous burns. Am J Pathol 1947;23: 695–720. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. King TC, Zimmerman JM. First‐aid cooling of the fresh burn. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1965;120: 1271–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. King TC, Zimmerman JM. Optimum temperatures for postburn cooling. Arch Surg 1965;91(4):656–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. King TC, Zimmerman JM, Price PB. Effect of immediate short‐term cooling on extensive burns. Surg Forum 1962;13: 487–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Demling RH, Mazess RB, Wolberg W. The effect of immediate and delayed cold immersion on burn edema formation and resorption. J Trauma 1979;19(1):56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Demling RH. Burns. N Engl J Med 1985;313(22): 1389–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stratta RJ, Saffle JR, Kravitz M, Warden GD. Management of tar and asphalt injuries. Am J Surg 1983;146(6):766–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leonard LG, Scheulen JJ, Munster AM. Chemical burns: effect of prompt first aid. J Trauma 1982;22(5):420–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hermans MHE, Vloemans AFPM. [A patient with a subungual burn caused by hydrofluoric acid]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1985;129(52):2510–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eldad A, Chaouat M, Weinberg A, Neuman A, Ben Meir P, Rotem M. Phosphorous pentachloride chemical burn – a slowly healing injury. Burns 1992;18(4):340–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Eldad A, Simon GA. The phosphorous burn – a preliminary comparative experimental study of various forms of treatment. Burns 1991;17(3): 198–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Iverson RE, Laub DR. Hydrofluoric acid burn therapy. Surg Forum 1970;21: 517–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Murao M. Studies on the treatment of hydrofluoric acid burn. Bull Osaka Med Coll 1989;35(1–2): 39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mangion SM, Beulke SH, Braitberg G. Hydrofluoric acid burn from a household rust remover. Med J Aust 2001;175(5):270–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. ABA. Advanced Life Support Providers Manual. Chicago, IL: American Burn Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pegg SP. Escharotomy in burns. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1992;21(5):682–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wong L, Spence RJ. Escharotomy and fasciotomy of the burned upper extremity. Hand Clin 2000;. 16(2):165–74, vii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tsoutsos D, Rodopoulou S, Keramidas E, Lagios M, Stamatopoulos K, Ioannovich J. Early escharotomy as a measure to reduce intraabdominal hypertension in full‐thickness burns of the thoracic and abdominal area. World J Surg 2003; 27(12):1323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hansbrough JF, Achauer B, Dawson J, Himel H, Luterman A, Slater H, Levenson S, Salzberg CA, Hansbrough WB, Dore C. Wound healing in partial‐thickness burn wounds treated with collagenase ointment versus silver sulfadiazine cream. J Burn Care Rehabil 1995;16(3 pt 1):241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ozcan C, Ergun O, Celik A, Corduk N, Ozok G. Enzymatic debridement of burn wound with collagenase in children with partial‐thickness burns. Burns 2002;28(8):791–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wilson AM, McGrouther DA, Eastwood M, Brown RA. The effect of burn blister fluid on fibroblast contraction. Burns 1997;23(4):306–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Uchinuma E, Koganei Y, Shioya N, Yoshizato K. Biological evaluation of burn blister fluid. Ann Plast Surg 1988;20(3):225–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Swain AH, Azadian BS, Wakeley CJ, Shakespeare PG. Management of blisters in minor burns. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;295(6591):181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rockwell WB, Ehrlich HP. Fibrinolysis inhibition in human burn blister fluid. J Burn Care Rehabil 1990;11(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rockwell WB, Ehrlich HP. Should burn blister fluid be evacuated? J Burn Care Rehabil 1990;11(1):93–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Reagan BJ, Staiano‐Coico L, LaBruna A, Mathwich M, Finkelstein J, Yurt RW, Goodwin CW, Madden MR. The effects of burn blister fluid on cultured keratinocytes. J Trauma 1996;40(3):361–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ortega MR, Ganz T, Milner SM. Human beta defensin is absent in burn blister fluid. Burns 2000;26(8):724–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ono I, Gunji H, Zhang JZ, Maruyama K, Kaneko F. A study of cytokines in burn blister fluid related to wound healing. Burns 1995;21(5):352–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Garner WL, Zuccaro C, Marcelo C, Rodriguez JL, Smith DJ Jr. The effects of burn blister fluid on keratinocyte replication and differentiation. J Burn Care Rehabil 1993;14(2 pt 1):127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Deitch EA, Smith BJ. The effect of blister fluid from thermally injured patients on normal lymphocyte transformation. J Trauma 1983;23(2):106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Deitch EA, Gelder F, McDonald JC. Biologic effect of blister fluid from thermal injuries on peripheral neutrophil chemotaxis. J Trauma 1982;22(2): 129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Janzekovic Z. Early surgical treatment of the burned surface. Panminerva Med 1972;14(7–8): 228–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Janzekovic Z. The burn wound from the surgical point of view. J Trauma 1975;15(1):42–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Monafo WW. Tangential excision. Clin Plast Surg 1974;1(4):591–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rosenberg L, Lapid O, Bogdanov‐Berezovsky A, Glesinger R, Krieger Y, Silberstein E, Sagi A, Judkins K, Singer AJ. Safety and efficacy of a proteolytic enzyme for enzymatic burn debridement: a preliminary report. Burns 2004;30(8): 843–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Levenson S. Supportive therapy in burn care. Debriding agents. J Trauma 1979;19(11 Suppl): 928–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jackson D, Topley W, Cason JS, Lowburry EJL. Primary excision and grafting of large burns. Ann. Surg 1969;167: 152–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hermans RP. De techniek van de behandeling van brandwonden. Leiden: Staphleu's wetenschappelijke uitgeversmaatschappy, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Herndon DN, Barrow RE, Rutan RL, Rutan TC, Desai MH, Abston S. A comparison of conservative versus early excision. Therapies in severely burned patients. Ann Surg 1989;209(5):547–52 (discussion 552–3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Tanner JC Jr, Vandeput J, Olley JF. The Mesh Skin Graft. Plast Reconstr Surg 1964;34: 287–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Vandeput J, Nelissen M, Tanner JC, Boswick J. A review of skin meshers. Burns 1995;21(5):364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Vandeput JJ, Tanner JC, Boswick J. Implementation of parameters in the expansion ratio of mesh skin grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;100(3): 653–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Meek CP. Microdermagrafting: the Meek technic. Hosp Top 1965;43: 114–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kreis RW, Mackie DP, Hermans RR, Vloemans AR. Expansion techniques for skin grafts: comparison between mesh and Meek island (sandwich‐) grafts. Burns 1994;20 Suppl 1: S39–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kreis RW, Mackie DP, Vloemans AW, Hermans RP, Hoekstra MJ. Widely expanded postage stamp skin grafts using a modified Meek technique in combination with an allograft overlay. Burns 1993;19(2):142–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lari AR, Gang RK. Expansion technique for skin grafts (Meek technique) in treatment severely burned patients. Burns 2001;27(1):61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Kilic A, Ozdengil E. Skin graft fixation by applying cyanoacrylate without any complication. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;110(1):370–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Buckley RC, Breazeale EE, Edmond JA, Brzezienski MA. A simple preparation of autologous fibrin glue for skin‐graft fixation. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;103(1):202–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Davey RB, Sparnon AL, Lodge M. Technique of split skin graft fixation using hypafix: a 15‐year review. ANZ J Surg 2003;73(11):958–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kreis RW, Vloemans AF. Fixation of skin transplants in burns with SurfaSoft and staples. An analysis of the results. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1987;21(3):249–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Vloemans AF, Kreis RW. Fixation of skin grafts with a new silicone rubber dressing (mepitel). Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1994;28(1):75–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Isago T, Nozaki M, Kikuchi Y, Honda T, Nakazawa H. Skin graft fixation with negative‐pressure dressings. J Dermatol 2003;30(9):673–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Scherer LA, Shiver S, Chang M, Meredith JW, Owings JT. The vacuum assisted closure device: a method of securing skin grafts and improving graft survival. Arch Surg 2002;137(8):930–3 (discussion 933‐4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Gallico GG III, O'Connor NE. Cultured epithelium as a skin substitute. Clin Plast Surg 1985;12(2):149–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gallico GG III, O'Connor NE, Compton CC, Kehinde O, Green H. Permanent coverage of large burn wounds with autologous cultured human epithelium. N Engl J Med 1984;311(7): 448–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Teepe RG, Ponec M, Kreis RW, Hermans RP. Improved grafting method for treatment of burns with autologous cultured human epithelium[letter]. Lancet 1986;1(8477):385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Boyce ST, Warden GD, Holder IA. Cytotoxicity testing of topical antimicrobial agents on human keratinocytes and fibroblasts for cultured skin grafts. J Burn Care Rehabil 1995;16(2 pt 1):97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Phillips TJ, Gilchrest BA. Clinical applications of cultured epithelium. Epithelial Cell Biol 1992;1(1):39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sheridan RL, Tompkins RG. Recent clinical experience with cultured autologous epithelium. Br J Plast Surg 1996;49(1):72–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Sheridan RL, Tompkins RG. Cultured autologous epithelium in patients with burns of ninety percent or more of the body surface. J Trauma 1995;38(1):48–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Kreis RW, Hoekstra MJ, Mackie DP, Vloemans AF, Hermans RP. Historical appraisal of the use of skin allografts in the treatment of extensive full skin thickness burns at the Red Cross Hospital Burns Centre, Beverwijk, The Netherlands. Burns 1992;18 Suppl 2: S19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Kreis RW, Vloemans AF, Hoekstra MJ, Mackie DP, Hermans RP. The use of non‐viable glycerol‐preserved cadaver skin combined with widely expanded autografts in the treatment of extensive third‐degree burns. J Trauma 1989;29(1): 51–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Alsbjorn BF. Clinical results of grafting burns with epidermal Langerhans' cell depleted allograft overlay. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 1991;25(1):35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Leicht P, Muchardt O, Jensen M, Alsbjorn BA, Sorensen B. Allograft vs. exposure in the treatment of scalds – a prospective randomized controlled clinical study. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1989;15(1):1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Eldad A, Din A, Weinberg A, Neuman A, Lipton H, Ben‐Bassat H, Chaouat M, Wexler MR. Cryopreserved cadaveric allografts for treatment of unexcised partial thickness flame burns: clinical experience with 12 patients. Burns 1997;23(7‐8): 608–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Rose JK, Desai MH, Mlakar JM, Herndon DN. Allograft is superior to topical antimicrobial therapy in the treatment of partial‐thickness scald burns in children. J Burn Care Rehabil 1997;18(4):338–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Gajiwala K, Gajiwala AL. Evaluation of lyophilised, gamma‐irradiated amnion as a biological dressing. Cell Tissue Bank 2004;5(2):73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ravishanker R, Bath AS, Roy R. ”Amnion Bank”– the use of long term glycerol preserved amniotic membranes in the management of superficial and superficial partial thickness burns. Burns 2003;29(4):369–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Maral T, Borman H, Arslan H, Demirhan B, Akinbingol G, Haberal M. Effectiveness of human amnion preserved long‐term in glycerol as a temporary biological dressing. Burns 1999;25(7):625–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Chang CJ, Yang JY. Frozen preservation of human amnion and its use as a burn wound dressing. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi 1994;17(4):316–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Dahinterova J, Dobrkovsky M. Treatment of the burned surface by amnion and chorion grafts. Sb Ved Pr Lek Fak Karlovy Univerzity Hradci Kralove 1969. (Suppl):513–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Chiu T, Pang P, Ying SY, Burd A. Porcine skin: friend or foe? Burns 2004;30(7):739–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Hassan Z, Shah M. Porcine xenograft dressing for facial burns: meshed versus non‐meshed. Burns 2004;30(7):753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Mis B, Rolland E, Ronfard V. Combined use of a collagen‐based dermal substitute and a fibrin‐based cultured epithelium: a step toward a total skin replacement for acute wounds. Burns 2004;30(7):713–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Heitland A, Piatkowski A, Noah EM, Pallua N. Update on the use of collagen/glycosaminoglycate skin substitute‐six years of experiences with artificial skin in 15 German burn centers. Burns 2004;30(5):471–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Ozerdem OR, Wolfe SA, Marshall D. Use of skin substitutes in pediatric patients. J Craniofac Surg 2003;14(4):517–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Wisser D, Steffes J. Skin replacement with a collagen based dermal substitute, autologous keratinocytes and fibroblasts in burn trauma. Burns 2003;29(4):375–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Barret JP, Dziewulski P, Wolf SE, Desai MH, Herndon DN. Outcome of scalp donor sites in 450 consecutive pediatric burn patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 1999;103(4):1139–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Madden MR, Nolan E, Finkelstein JL, Yurt RW, Smeland J, Goodwin CW, Hefton J, Staiano‐Coico L. Comparison of an occlusive and a semi‐occlusive dressing and the effect of the wound exudate upon keratinocyte proliferation. J Trauma 1989;29(7):924–30 (discussion 930‐1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Zapata‐Sirvent R, Hansbrough JF, Carroll W, Johnson R, Wakimoto A. Comparison of biobrane and scarlet red dressings for treatment of donor site wounds. Arch Surg 1985;120(6): 743–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Innes ME, Umraw N, Fish JS, Gomez M, Cartotto RC. The use of silver coated dressings on donor site wounds: a prospective, controlled matched pair study. Burns 2001;27(6):621–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Hansbrough W. Nursing care of donor site wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil 1995;16(3 pt 1):337–9 (discussion 339‐40). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Hyland WT. A painless donor‐site dressing. Plast Reconstr Surg 1982;69(4):703–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Smith DJ Jr, Thomson PD, Garner WL, Rodriguez JL. Donor site repair. Am J Surg 1994;167(1A): 49S–51S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Brezel BS, McGeever KE, Stein JM. Epinephrine v thrombin for split‐thickness donor site hemostasis. J Burn Care Rehabil 1987;8(2):132–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Attwood AI. Calcium alginate dressing accelerates split skin graft donor site healing. Br J Plast Surg 1989;42(4):373–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Hermans MHE. Results of a survey on the use of different treatment options for partial and full thickness burns. Burns 1998;24(6):539–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Gear AJ, Hellewell TB, Wright HR, Mazzarese PM, Arnold PB, Rodeheaver GT, Edlich RF. A new silver sulfadiazine water soluble gel. Burns 1997;23(5):387–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Monafo WW, Ayvazian VH. Topical therapy. Surg Clin North Am 1978;58(6):1157–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Klasen HJ. A historical review of the use of silver in the treatment of burns. II. Renewed interest for silver. Burns 2000;26(2):131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Fox CL Jr. Silver sulfadiazine for control of burn wound infections. Int Surg 1975;60(5):275–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Barret JP, Dziewulski P, Ramzy PI, Wolf SE, Desai MH, Herndon DN. Biobrane versus 1% silver sulfadiazine in second‐degree pediatric burns. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000;105(1):62–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Jarrett F, Ellerbe S, Demling R. Acute leukopenia during topical burn therapy with silver sulfadiazine. Am J Surg 1978;135(6):818–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Fraser GL, Beaulieu JT. Leukopenia secondary to sulfadiazine silver. JAMA 1979;241(18):1928–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Caffee HH, Bingham HG. Leukopenia and silver sulfadiazine. J Trauma 1982;22(7):586–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Lockhart SP, Rushworth A, Azmy AA, Raine PA. Topical silver sulphadiazine: side effects and urinary excretion. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1983;10(1):9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Gbaanador GB, Policastro AJ, Durfee D, Bleicher JN. Transient leukopenia associated with topical silver sulfadiazine in burn therapy. Nebr Med J 1987;72(3):83–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Choban PS, Marshall WJ. Leukopenia secondary to silver sulfadiazine: frequency, characteristics and clinical consequences. Am Surg 1987;53(9): 515–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Eaglstein WH, Mertz PM, Falanga V. Occlusive dressings. Am Fam Physician 1987;35(3):211–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. James JH, Watson AC. The use of opsite, a vapour permeable dressing, on skin graft donor sites. Br J Plast Surg 1975;28(2):107–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Harding KG, Jones V, Price P. Topical treatment: which dressing to choose. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2000;16 Suppl 1: S47–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Gotschall CS, Morrison MI, Eichelberger MR. Prospective, randomized study of the efficacy of mepitel on children with partial‐thickness scalds. J Burn Care Rehabil 1998;19(4):279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Benbow M, Iosson G. A clinical evaluation of urgotul to treat acute and chronic wounds. Br J Nurs 2004;13(2):105–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Meaume S, Senet P, Dumas R, Carsin H, Pannier M, Bohbot S. Urgotul: a novel non‐adherent lipidocolloid dressing. Br J Nurs 2002;11 (16 Suppl):S42–3, S46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Hermans MHE, Hutchinson JJ. Advantages of Occlusive Dressings. London: Springer Verlag, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 140. Caruso DM, Foster KN, Hermans MH, Rick C. Aquacel Ag in the management of partial‐thickness burns: results of a clinical trial. J Burn Care Rehabil 2004;25(1):89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Kneafsey B, O'Shaughnessy M, Condon KC. The use of calcium alginate dressings in deep hand burns. Burns 1996;22(1):40–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Parsons D, Bowler PG, Walker M. Polishing the information on silver. Ostomy wound manage 2003;. 49(8):10–1 (author reply 11‐2, 14, 16 passim). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Demling RH, DeSant L. Effects of silver on wound management. Wounds 2001;13(1): 23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 144. Keswani MH, Patil AR. The boiled potato peel as a burn wound dressing: a preliminary report. Burns Incl Therm Inj 1985;11(3):220–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Van Baare J, Ligtvoet EE, Middelkoop E. Microbiological evaluation of glycerolized cadaveric donor skin. Transplantation 1998;65(7):966–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Noordenbos J, Dore C, Hansbrough JF. Safety and efficacy of transcyte for the treatment of partial‐thickness burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1999;20(4):275–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Kumar RJ, Kimble RM, Boots R, Pegg SP. Treatment of partial‐thickness burns: a prospective, randomized trial using transcyte. ANZ J Surg 2004;74(8):622–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Bello YM, Falabella AF, Eaglstein WH. Tissue‐engineered skin. Current status in wound healing. Am J Clin Dermatol 2001;2(5):305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Parente ST. Estimating the economic cost offsets of using dermagraft‐TC as an alternative to cadaver allograft in the treatment of graftable burns. J Burn Care Rehabil 1997;18(1 pt 2):S18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Hansbrough JF, Mozingo DW, Kealey GP, Davis M, Gidner A, Gentzkow GD. Clinical trials of a biosynthetic temporary skin replacement, dermagraft‐transitional covering, compared with cryopreserved human cadaver skin for temporary coverage of excised burn wounds. J Burn Care Rehabil 1997;18(1 pt 1):43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Hansbrough J. Dermagraft‐TC for partial‐thickness burns: a clinical evaluation. J Burn Care Rehabil 1997;18(1 pt 2):S25–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Still J, Glat P, Silverstein P, Griswold J, Mozingo D. The use of a collagen sponge/living cell composite material to treat donor sites in burn patients. Burns 2003;29(8):837–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Deitch EA, Wheelahan TM, Rose MP, Clothier J, Cotter J. Hypertrophic burn scars: analysis of variables. J Trauma 1983;23(10):895–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Worley CA. The wound healing process: part III – the finale. Dermatol Nurs 2004;16(3):274, 295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Roques C. Pressure therapy to treat burn scars. Wound Repair Regen 2002;10(2):122–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Rochet JM, Zaoui A. [Burn scars: rehabilitation and skin care]. Rev Prat 2002;52(20):2258–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Puzey G. The use of pressure garments on hypertrophic scars. J Tissue Viability 2002;12(1):11–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Jordan RB, Daher J, Wasil K. Splints and scar management for acute and reconstructive burn care. Clin Plast Surg 2000;27(1):71–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Ayhan M, Gorgu M, Silistreli KO, Aytug Z, Erdogan B. Silastic sheet integrated polymethylmetacrylate splint in addition to surgery for commissure contractures complicated with hypertrophic scar. Acta Chir Plast 2004;46(4): 132–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Van den Kerchhove E, Boeckx W, Kochuyt A. Silicone patches as a supplement for pressure therapy to control hypertrophic scarring. J Burn Care Rehabil 1991;12(4):361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. Kavanagh GM, Page P, Hanna MM. Silicone gel treatment of extensive hypertrophic scarring following toxic epidermal necrolysis. Br J Dermatol 1994;130(4):540–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Haedersdal M, Poulsen T, Wulf HC. Laser induced wounds and scarring modified by antiinflammatory drugs: a murine model. Lasers Surg Med 1993;13(1):55–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Beldon P. Management of scarring. J Wound Care 1999;8(10):509–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Lupton JR, Alster TS. Laser scar revision. Dermatol Clin 2002;20(1):55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Liew SH, Murison M, Dickson WA. Prophylactic treatment of deep dermal burn scar to prevent hypertrophic scarring using the pulsed dye laser: a preliminary study. Ann Plast Surg 2002;49(5): 472–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Xiang J, Wang XQ, Qing C, Liao ZJ, Lu SL. [The influence of dermal template on the expressions of signal transduction protein Smad 3 and transforming growth factorbeta1 and its receptor during wound healing process in patients with deep burns]. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi 2005; 21(1):52–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Suliman MT. Experience with the seven flap‐plasty for the release of burns contractures. Burns 2004;30(4):374–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Deb R, Giessler GA, Przybilski M, Erdmann D, Germann G. [Secondary plastic surgical reconstruction in severely burned patients]. Chirurg 2004;75(6):588–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Lu KH, Guo SZ, Ai YF, Ma XJ. [Management of severe postburn scar contracture in the lower extremities]. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi 2004;20(2):69–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Selezneva LG. Keloid scars after burns. Acta Chir Plast 1976;18(2):106–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Iudenich VV, Pal'tsyn AA, Zalugovskii OG. [Electron microscopic and autoradiographic study of keloid scars]. Arkh Patol 1982;44(1): 44–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Bang RL, Dashti H. Keloid and hypertrophic scars: trace element alteration. Nutrition 1995;11(5 Suppl):527–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Morison WL. Oral treatment of keloid. Med J Aust 1968;1(10):412–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174. Donati L, Taidelli Palmizi GA. [Treatment of hypertrophic and keloid cicatrices with thiomucase]. Minerva Chir 1975;30(6):326–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. Tammelleo AD. Suit for post‐operative scar: keloid or burn? Regan Rep Nurs Law 1996;37(4):4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176. Ahlering PA. Topical silastic gel sheeting for treating and controlling hypertrophic and keloid scars: case study. Dermatol Nurs 1995;7(5): 295–7, 322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177. Sizov VM. [The diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic and keloid scars]. Klin Khir 1994;9: 41–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]