Abstract

The concept of moist wound healing is not fully implemented in daily practice in Germany. Thus, the objective of this investigation was to evaluate the use of Tielle hydropolymer dressings in chronic exuding wounds in primary care. A total of 6993 patients with pressure sores (26·6%), venous leg ulcers (59·8%), diabetic foot disease (9·5%) and other wounds (5·1%) were enrolled into three multicentre, open‐label, single‐arm, prospective phase‐IV studies for an observational period of either 4 or 12 weeks. Within the 4 (12)‐week study using Tielle, 43·3% (59·1%) of the wounds healed and 51·6% (36·9%) improved. Wound area was reduced by 78·2% (85·1%). Medium or strong levels of exudates were reduced from 57·4% to 6·7% (4·0%). Cosmetic results were excellent or good in 96·3%. Compared with patients' previous treatment, efficacy and tolerability were assessed as better or much better in 92·5% and 70·4%, respectively. 97·1% of the patients remained free of adverse events. The frequency of dressing changes was reduced from 5 to 3 per week (−43%). Tielle provides an effective and safe dressing in the management of chronic exuding wounds in primary care improving patient's comfort. Due to longer wearing times, Tielle may also be cost saving.

Keywords: Chronic exuding wounds, Hydropolymer dressing, Tielle, Tolerability

Introduction

The treatment of chronic wounds such as pressure ulcers (PU), venous leg ulcers (VLU) and diabetic foot disease (DFD) is challenging and requires advanced wound management. Exudation from these chronic wounds is a critical factor in effective wound management, and the advantages of moist wound healing have been widely accepted 1, 2, 3). Therefore, dressings that regulate wound exudate and establish an optimal wound moisture by interacting with the exudate achieve higher healing rates (4). If wounds are too wet, the risk for maceration and wound enlargement (5) increases. If wounds are too dry, wound healing is delayed (6).

For the selection of an appropriate dressing, several clinical and non clinical variables should be considered. The ideal dressing should maintain a moist environment, provide a barrier against bacteria and physical factors and should prevent maceration (1, 3). Moreover, practical considerations with regard to handling of the dressing, patient's comfort and wearing time of the dressing (which translates into cost effectiveness) are important (7, 8). During recent years, modern dressings including hydrocolloids, alginates and foams have been developed to address these issues.

Hydrocolloids were among the first dressings that encouraged a moist wound environment and are effective in managing low‐to‐moderate levels of exudate (1, 3). They should not be used in infected wounds or in wounds with increased risk of infection such as DFD (3). Disadvantages of hydrocolloid dressings include development of wound odour (9), sensitivity and allergic reactions 10, 11, 12, 13) and maceration (14).

Alginates are highly absorbable biodegradable dressings, which are useful for moderately to heavily exuding wounds (3, 15). They can be removed painlessly (5). During alginate treatment, a secondary dressing is often required to keep the dressing in place (1, 14).

Tielle dressings are a complex construct consisting of a highly absorbent central hydropolymer foam, a wicking layer and a polyurethane backing (16, 17). They handle exudate by both absorbancy (because of the hydropolymer) and moisture vapour transmission through the semipermeable backing. The latter acts also as a barrier to microorganisms. The application of Tielle is mainly recommended for wounds with low‐to‐moderate exudate (16).

The objective of these studies was to assess Tielle dressings in the treatment of chronic exuding wounds under daily practice conditions with regard to efficacy, tolerability and handling. To evaluate wound‐type‐specific differences, patients with PU, VLU, DFD and other wounds were included in this trial.

Patients and methods

Study design

The data reported are derived from three multicentre, open‐label, single‐arm, prospective observational phase IV studies, which were conducted by physicians (general practitioners, dermatologists and surgeons) throughout Germany from 1996 to 2000. Two studies (2770 and 1868 patients, respectively) monitored the use of the dressing over a period of 4 weeks, one study (2355 patients) over 12 weeks (total 6993 patients). The wound care procedures and decisions of the physicians were not influenced. They were completely free to select which patients to treat with the test dressing, which diagnostic measures they used and the way in which they controlled the course of treatment or which concurrent or additional measures they undertook to improve healing. They collected data on the background characteristics of the patients and on key efficacy variables and adverse events (AE) in a case report form (CRF). If any severe AE occurred, the physicians were obliged to report them by completing a form within 24 hours and transmitting it to the manufacturer, who forwarded the report in a standardised form to the relevant authorities [Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte (BfArM)]. The collected data and CRFs were not verified by comparing with the source data in the patient files, but the forms were routinely checked for plausibility and completeness. The federal panel doctors' association (Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung) as well as the higher authorities (BfArM) were informed of this investigation. The participating doctors received a small monetary reward for the completion of documentation required for each patient, which is common practice for this type of study in Germany.

Patients and study conduct

The physicians selected patients, with exuding chronic wounds of at least 4‐week duration, for the application of Tielle dressing. Therapy was adjusted to the individual severity of symptoms and the course of healing. There were no exclusion criteria regarding age, concomitant treatment or concomitant diseases. Study visits were at baseline (before starting treatment with Tielle) after 4‐ or 12‐week treatment, respectively.

The parameters documented in the study included demographic characteristics (age and sex), medical diagnoses (wound type, wound age, localisation of the wound, pre‐treatment and concomitant diseases) and wound characteristics (signs of infection, wound radius/depth/area, exudation, wound odour, necrosis, fibrinous slough, granulation tissue and epithelialisation). Estimation of the degree of exudates present was assessed on a 4‐point scale (1 – none, 2 – little/small, 3 – medium/extensive and 4 – strong/entire area). The described wound characteristics were analysed at baseline and at study end. If patients developed a wound infection, it was noted as was the antimicrobial treatment given. The overall wound status (healed, improved, unchanged and aggravated) and the cosmetic results (excellent, good, moderate and unsatisfactory) were rated on a 4‐point scale at the study end. Physicians rated the efficacy, tolerability, handling of Tielle treatment and the compliance of the patients compared with previous treatment (scale: much better, better, equal and worse) after finishing the treatment. The number of dressing changes per week was also recorded.

Statistical considerations

Statistical analysis included descriptive data and was interpreted in an explorative way. Data from three studies were included in a pooled analysis. This was possible, because the CRFs of the different studies were almost identical with regard to main efficacy and safety data. For efficacy, changes of wound radius (cm) and wound area (%) were determined. Comparisons were carried out for signs of infection, levels of exudation, wound odour, portion of necrotic tissue and portion of fibrinous adhesion between baseline and the postbaseline visit at 4 or 12 months, respectively. The absolute and relative frequencies of AE and the efficacy and tolerability ratings were reported.

The statistical analysis was performed with the software package sas[version 6·12 for Windows NT4 (18)]. In terms of safety, the trial was designed adequately to identify rare events that may not have been detected in previous clinical studies.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 summarises the baseline patients and wound characteristics. A total of 6993 patients were included into this pooled analysis. Of these, 61·4% were female. Mean age was 67·8 (±14·9) years (range of 3–101). The most frequent wounds were VLU and PU, followed by DFD and other wounds (posttraumatic, postoperative and other aetiology). Mean wound age was 7·8 months indicating the presence of problematic wounds, and median wound age was 3 months. 49·2% of the wounds showed signs of infection independent on the wound‐type present. Moderate and strong levels of exudate occurred in 57·4% and wound odour in 37·6%. Extensive necrosis and fibrinous adhesion were seen in approximately one‐third of the participants (33·0% and 34·1%). A total of 86·8% of patients had been pre‐treated, predominantly with wound ointments, lint/fleece pad or antimicrobial gauze, respectively, and 10·9% had received hydrocolloid dressings.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and wound characteristics at baseline

| Baseline characteristics | Total (n = 6993) | PU (n = 1793) | VLU (n = 4180) | DFD (n = 662) | Other wounds (n = 358) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years ± SD) | 67·8 ± 14·9 | 74·5 ± 13·6 | 67·0 ± 12·7 | 62·4 ± 16·8 | 53·4 ± 22·1 |

| Gender (%) | |||||

| Male | 37·9 | 37·5 | 35·5 | 50·0 | 46·9 |

| Female | 61·4 | 61·6 | 64·0 | 49·2 | 52·8 |

| Wound type (%) | 100·0 | 25·9 | 59·8 | 9·5 | 5·1 |

| Wound age (months) | |||||

| Mean | 7·8 | 3·7 | 10·0 | 6·0 | 6·1 |

| Median | 3·0 | 2·0 | 3·0 | 2·0 | 1·3 |

| Wound radius (cm) | |||||

| Mean ± SD | 2·2 ± 1·5 | 2·6 ± 1·6 | 2·1 ± 1·4 | 1·9 ± 1·4 | 2·2 ± 1·6 |

| Wound depth (%) | |||||

| Superficial | 42·1 | 4·5 | 44·5 | 32·3 | 4·2 |

| Deep | 42·9 | 38·6 | 44·5 | 46·7 | 4·2 |

| Wound pouch | 6·3 | 9·2 | 4·8 | 8·9 | 3·6 |

| Deep/pouch | 5·1 | 9·2 | 2.5 | 9·1 | 12·6 |

| Infection (%) | |||||

| Present | 49·2 | 49·1 | 47·2 | 57·6 | 57·8 |

| Exudation (%) | |||||

| None | 4·6 | 5·0 | 4·1 | 6·0 | 6·7 |

| Little | 37·2 | 4·0 | 36·7 | 36·4 | 32·1 |

| Medium | 44·0 | 4·8 | 45·8 | 43·8 | 4·5 |

| Strong | 13·4 | 14·0 | 12·8 | 12·7 | 18·4 |

| Wound odour (%) | |||||

| None | 22·1 | 16·2 | 23·9 | 21·8 | 31·0 |

| Little | 38·8 | 38·0 | 39·7 | 37·3 | 35·5 |

| Medium | 26·2 | 28·4 | 25·4 | 28·5 | 21·2 |

| Strong | 11·4 | 16·2 | 9·5 | 11·5 | 1·3 |

| Portion of necrotic tissue (%) | |||||

| None | 18·6 | 15·6 | 19·9 | 15·9 | 24·6 |

| Small | 47·8 | 46·1 | 49·8 | 43·7 | 41·6 |

| Extensive | 28·2 | 32·3 | 25·6 | 32·8 | 29·1 |

| Entire area | 4·8 | 5·5 | 4·2 | 7·3 | 3·9 |

| Portion of fibrinous adhesion (%) | |||||

| None | 1·7 | 11·0 | 9·7 | 13·4 | 15·9 |

| Small | 54·0 | 54·6 | 53·9 | 54·2 | 51·4 |

| Extensive | 3·7 | 31·1 | 31·5 | 26·9 | 26·0 |

| Entire area | 3·4 | 2·3 | 3·6 | 4·2 | 4·5 |

DFD, diabetic foot disease; SD, standard deviation; VLU, venous leg ulcers; PU, pressure ulcers.

Pooled data from two 4‐week and one 12‐week Phase‐IV studies.

Reasons for changing to Tielle dressings

The most important reason for switching to Tielle was lack of efficacy (67·8%) of the previous treatment. Handling (13·9%), debridement (14·3%), compliance (12·6%) and frequent changes (11·4%) were other reasons noted.

Type, duration and frequency of application

The most frequent dressing size was 7 × 9 cm (69·2%), followed by 11 × 11 cm (20·5%). Sacrum‐sized dressings were largely used in patients with PU. The average duration of Tielle treatment in the 4‐week study was 40·5 days and in the 12‐week study 57·4 days. The treatment periods of other wounds were shorter compared with that of the other wound types in all studies [mean (median) values: 30·4 (27·0) days; 42·7 (35·0) days, respectively]. In the study, bandages were changed three times per week (median) compared with five times per week (median) during previous treatment. This represents a reduction of 42·9% per week. In the subgroup with PU, a greater reduction was seen [from six to three changes (50%) per week].

Efficacy

Tielle treatment had a positive effect on wound healing in 95% (96%) of the patients in the 4 (12)‐week studies (Figure 1a). Only a small percentage of patients did not benefit. Figure 1b displays differences in subgroups with respect to healing rates. Highest rates were obtained in patients with other wounds compared with that in the other subgroups [57·9% (73·8%)]. Regarding infected wounds, 39·0% (55·5%) healed.

Figure 1.

(a) Assessment of overall wound status after completion of Tielle treatment (b) Assessment of overall wound status after completion of Tielle treatment in different wound types. Values do not add up to 100% because of missing data and/or rounding.

The median duration of treatment until wound healing was 42 (49) days in the 4 (12)‐week studies. Compared to the overall duration, other wounds healed more quickly [25 (34) days].

Table 2 summarises the outcomes of Tielle treatment in relation to individual wound characteristics. Overall wound radius and wound area were reduced by 69·2% (8·2%) and 78·2% (85·1%) on average, respectively, after 4 (12) weeks. For these parameters, no major differences between wound types were noted, except for other wounds [greater effects for wound radius = −77·7% (−83·0%) and wound area = −85·2% (−86·2%)].

Table 2.

Outcomes of treatment with Tielle dressings after 4 weeks and 12 weeks *

| Total | PU | VLU | DFD | Other wounds | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 4 weeks† | 12 weeks‡ | Baseline | 4 weeks† | 12 weeks‡ | Baseline | 4 weeks† | 12 weeks‡ | Baseline | 4 weeks† | 12 weeks‡ | Baseline | 4 weeks† | 12 weeks‡ | ||

| (n = 6993) | (n = 4628) | (n = 2355) | (n = 1793) | (n = 1181) | (n = 606) | (n = 4180) | (n = 2862) | (n = 1313) | (n = 662) | (n = 394) | (n = 268) | (n = 358) | (n = 190) | (n = 168) | ||

| Changes of wound radius (%) | −69·2 | −78·2 | −67·4 | −79·1 | −69·3 | −77·1 | −71·6 | −78·5 | −77·7 | −83.0 | ||||||

| Changes of wound area (%) | −78·2 | −85·1 | −77·9 | −87·5 | −78·8 | −83·8 | −71·8 | −84·8 | −85·2 | −86·2 | ||||||

| Signs of infection (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| Present | 49·2 | 5·5 | 3·4 | 49·1 | 6·3 | 2·5 | 47.2 | 5·1 | 3·7 | 57·6 | 5·6 | 4·1 | 57·8 | 6·8 | 3·6 | |

| Exudation (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 4·6 | 18·6 | 14·5 | 5·0 | 21·3 | 12·9 | 4·1 | 18·2 | 15·2 | 6·0 | 17·5 | 18·7 | 6·7 | 10·0 | 8·3 | |

| Healed | N/A | 43·3 | 59·1 | N/A | 38·9 | 57·8 | N/A | 43·1 | 57·9 | N/A | 51·5 | 59·0 | N/A | 57·9 | 73·8 | |

| Little | 37·2 | 29·8 | 19·6 | 40·0 | 31·1 | 24·3 | 36·7 | 30·5 | 19·4 | 36·4 | 25·4 | 15·7 | 32·1 | 19·5 | 10·7 | |

| Medium | 44·0 | 5·5 | 3·8 | 40·8 | 5·8 | 3·0 | 45·8 | 5·5 | 4·3 | 43·8 | 4·1 | 3·0 | 40·5 | 6·3 | 4·2 | |

| Strong | 13·4 | 1·2 | 1·2 | 14·0 | 1·1 | 0·8 | 12·8 | 1·3 | 1·3 | 12·7 | 0·5 | 0·7 | 18·4 | 2·1 | 2·4 | |

| Wound odour (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 22·1 | 37·1 | 14·5 | 16·2 | 37·0 | 28·4 | 23·9 | 38·4 | 29·8 | 21·8 | 32·0 | 27·6 | 31·0 | 29·5 | 18·5 | |

| Healed | N/A | 43·3 | 59·1 | N/A | 38·9 | 57·8 | N/A | 43·1 | 57·9 | N/A | 51·5 | 59·0 | N/A | 57·9 | 73·8 | |

| Little | 38·8 | 13·6 | 19·6 | 38·0 | 16·9 | 10·7 | 39·7 | 12·9 | 7·7 | 37·3 | 11·4 | 9·0 | 35·5 | 8·4 | 5·4 | |

| Medium | 26·2 | 2·7 | 3·8 | 28·4 | 3·8 | 0·8 | 25·4 | 2·4 | 2·2 | 28·5 | 2·5 | 0·7 | 21·2 | 1·1 | 1·8 | |

| Strong | 11·4 | 1·2 | 1·2 | 16·2 | 1·0 | 0·3 | 9·5 | 1·4 | 0·4 | 11·5 | 0·8 | 0·4 | 10·3 | 0·5 | 0·6 | |

| Portion of necrotic tissue (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 18·6 | 36·7 | 25·2 | 15·6 | 36·7 | 24·3 | 19·9 | 38·3 | 27·0 | 15·9 | 29·4 | 24·3 | 24·6 | 27·4 | 16·1 | |

| Healed | N/A | 43·3 | 59·1 | NA | 38·9 | 57·8 | N/A | 43·1 | 57·9 | N/A | 51·5 | 59·0 | N/A | 57·9 | 73·8 | |

| Small | 47·8 | 16·3 | 12·7 | 46·1 | 19·5 | 15·2 | 49·8 | 15·6 | 12·3 | 43·7 | 14·7 | 11·9 | 41·6 | 10·5 | 8·3 | |

| Extensive | 28·2 | 1·7 | 1·3 | 32·3 | 2·9 | 1·5 | 25·6 | 1·3 | 1·1 | 32·8 | 1·3 | 1·5 | 29·1 | 2·1 | 1·8 | |

| Entire area | 4·8 | 0·4 | 0·3 | 5·5 | 0·5 | 0·3 | 4·2 | 0·4 | 0·3 | 7·3 | 0·8 | 0·4 | 3·9 | 0·0 | 0·0 | |

| Portion of fibrinous adhesion (%) | ||||||||||||||||

| None | 1·7 | 21·7 | 16·6 | 11·0 | 23·2 | 16·2 | 9·7 | 21·9 | 17·4 | 13·4 | 17·8 | 17·2 | 15·9 | 16·8 | 11·9 | |

| Healed | N/A | 43·3 | 59·1 | N/A | 38·9 | 57·8 | N/A | 43·1 | 57·9 | N/A | 51·5 | 59·0 | N/A | 57·9 | 73·8 | |

| Small | 54·0 | 27·9 | 18·6 | 54·6 | 29·7 | 20·8 | 53·9 | 28·5 | 18·6 | 54·2 | 24·1 | 18·7 | 51·4 | 15·8 | 10·7 | |

| Extensive | 3·7 | 4·5 | 3·4 | 31·1 | 5·2 | 3·3 | 31·5 | 4·3 | 3·6 | 26·9 | 3·0 | 2·2 | 26·0 | 5·8 | 3·6 | |

| Entire area | 3·4 | 0·6 | 0·6 | 2·3 | 0·6 | 0·8 | 3·6 | 0·6 | 0·5 | 4·2 | 1·0 | 0·4 | 4·5 | 0·0 | 0·0 | |

N/A, not applicable; DFD, diabetic foot disease; SD, standard deviation; VLU, venous leg ulcers; PU, pressure ulcers.

Pooled data from two 4‐week and one 12‐week Phase‐IV studies.

Two studies.

One study.

The frequency of infections decreased from 49·2% at baseline to 5·5% (3·4%). No differences with respect to wound types were observed. As for exudation after 4 (12)‐week treatment with Tielle, strong and medium exudation occurred in 1·2% (1·2%) and 5·5% (3·8%) compared with 13·4% and 44·0% at baseline. Little exudate was noted in one‐third and one‐fifth of the patients after the 4‐ and 12‐week observation periods, respectively.

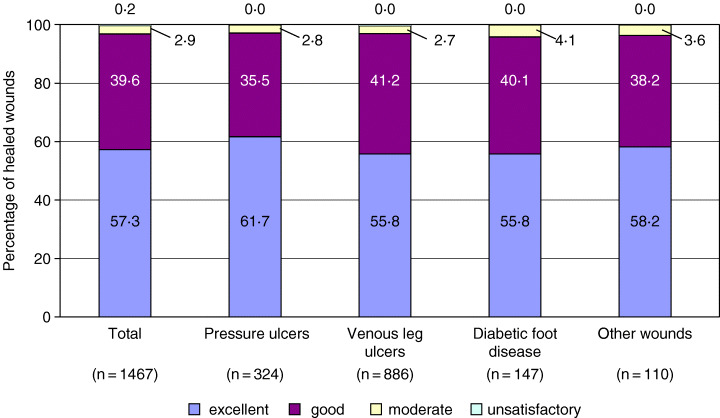

Physicians' ratings

Physicians' ratings of cosmetic results were excellent or good in 96·9% of the healed wounds. Figure 2 displays that excellent cosmetic results were more frequent in pressure sores compared with other wound types. Unsatisfactory cosmetic results were noted in VLU at a small percentage (0·3%) only.

Figure 2.

Assessment of cosmetic results of healed wounds after completion of Tielle treatment. Values do not add up to 100% because of misssing data and/or rounding.

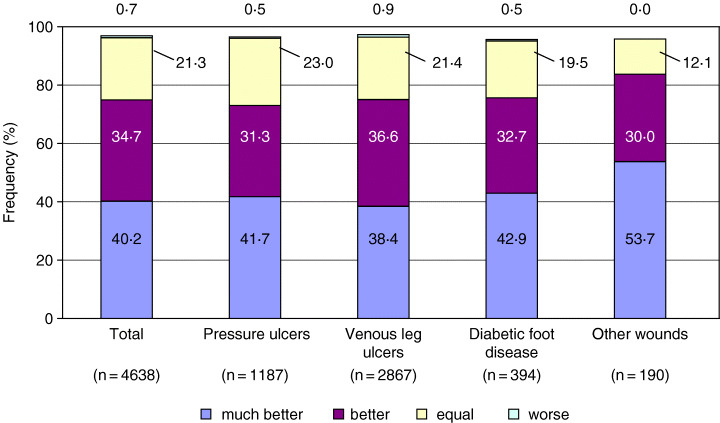

The efficacy of Tielle was assessed by the physicians as much better in 59·0% and better in 33·5% of the patients compared with that of previous treatment. The proportion of much better efficacy was highest in patients with other wounds (64·5%) and PU (62·5%) (Figure 3). Worse efficacy was only noted in 0·9% of patients.

Figure 3.

Assessment of efficacy of Tielle in comparison to previous treatment. Values do not add up to 100% because of missing data and/or rounding.

Figure 4 shows that there were differences in the assessment of tolerability, handling and compliance between the wound types. Other wounds were assessed most frequently as much better (tolerability: 49·7%; handling: 62·3%; compliance: 53·7%). VLU seemed to be the most difficult wound as assessed with these (tolerability: 38·1%; handling: 49·6%; compliance: 38·4%).

Figure 4.

Compliance with Tielle treatment in comparison to previous treatment. Values do not add up to 100% because of missing data and/or rounding.

Safety

A total of 4·5% of the patients withdrew from the studies prematurely. The most frequent reasons were insufficient efficacy (0·5%), intolerance (0·5%) and worsening of the wound (0·4%). Twenty‐nine (0·4%) patients died during the study (not related to Tielle treatment). AE were rare and occurred only in a total of 205 patients (2·9%). The frequency of AE slightly differed for individual wound types (PU = 0·7%; VLU = 4·1%; DFD = 2·1%; other wounds = 2·2%). The most frequently reported AE were pain (0·8%), general intolerance (0·6%) and itching (0·5%).

Adjustment of the standard therapy

At study end, the vast majority of the physicians (96·1%) wanted to include Tielle to their standard therapy of chronic wound healing independent of the wound type. Reasons given were mainly clinical efficacy (23·7%) and handling (14·1%) of Tielle dressing.

Discussion

The management of chronic exuding wounds is a challenging and sometimes frustrating task for physicians in primary care. Wound dressings may have a substantial influence on wound healing and should be based on the principle of moist wound healing (1). For the selection of a given dressing efficacy in terms of wound healing, easy application and maintenance of the dressing and quality‐of‐life aspects (painless removal, tolerability and low frequency of bandage changes) should be taken into account (9). Because chronic wounds remain one of the most costly problems in health care today (1), cost effectiveness plays an important role in dressing selection.

The present observational phase‐IV study investigated properties of Tielle hydropolymer dressing in the management of chronic exuding wounds in a large primary care sample. We would accept that the study design is not conventional. However, the key findings of this study are

-

•

ninety‐five percent of the patients benefited from the use of Tielle dressings in terms of efficacy

-

•

the patients' quality of life was improved by high tolerability, easy handling and low rate of AE

-

•

Tielle may also be cost saving because of longer wear time.

Methodological considerations

Patients with different kinds of chronic exuding wounds were included in this study without traditional exclusion criteria regarding patient or wound age or comorbid diseases in order to obtain a typical picture of a primary care setting. However, the absence of a control and comparative group makes it difficult to estimate the efficacy, tolerability and handling of Tielle in direct comparison with other dressings.

Efficacy

Almost all patients (95%) benefited from switching to the Tielle hydropolymer dressing independent of the wound type. In particular, the efficacy of Tielle was the greatest in subjects with other wounds in which the healing rate was about 15% higher than the average. Surprisingly, Tielle was beneficial in infected wounds, and longer treatment duration with Tielle increased the rate of healing. These results are consistent with data from a similar observational study using a different type of Tielle dressing (19).

A substantial number of studies previously reported that Tielle hydropolymer dressings were highly effective in the management of acute and chronic wounds and showed advantages compared with hydrocolloid dressings (7, 9, 14, 16, 20, 21). Collier reported that Tielle was more effective compared with hydrocolloid dressings with respect to improvement rate and wound odour in VLU (9). A further study in patients with leg ulcers and pressure sores documented that Tielle was superior to Granuflex hydrocolloid dressings with regard to reduction of leg ulcer area and odour production (14). No significant difference concerning the rate of healing was observed between Tielle and a new soft silicone dressing (22). In both the Tielle and the silicone group, the healing rate was about 50% and which corresponds to the rate in the present study.

Tolerability and handling

An important finding in our study was that the vast majority of patients tolerated Tielle treatment much better or better than previous other treatments. This was reflected by a very low incidence of AE. Comparing Tielle and Granuflex hydrocolloid dressings, no difference in overall AE was reported in patients with leg ulcers and PU (14); however, maceration only occurred in the Granuflex subgroup. Recently, a study including 38 patients with stage II PU compared Tielle with silicone dressings (22). At the final visit after 8 weeks, no difference between the groups was seen. The symptoms reported as tissue damage were mainly redness and new ulcers. In contrast to this small study, in the present study, redness was only found in 14 patients (0·2%) and ulceration in one patient (0·01%) indicating that tissue damage was not a major problem in a sample size of 6993 subjects.

The present study provides convincing results regarding handling of Tielle: a total of 87·0% of patients assessed handling of Tielle much better or better compared with previous treatment. This is consistent with findings from previous studies (9, 14). Tielle was significantly easier and more comfortable to use than hydrocolloid dressings, especially the removal from the wounds did not cause any trauma (9, 14). The acceptance of the Tielle therapy was high in the present study, which was reflected by an improved compliance in 75% of patients.

Cost saving

Because chronic wounds can last for many months, cost effectiveness is a key factor for dressing selection. Main costs in the treatment of chronic wounds include the time spent by doctors or nurses applying or removing dressings (23). Thus, the decision for an appropriate dressing should primarily consider the wearing time of a dressing and the frequency of bandage changes (8). An important finding in our study was the reduction of bandage changes by nearly 50% compared with previous treatment. The prolonged wearing time could be explained by the ability of Tielle to handle fluid by both an improved absorption and moisture vapour transmission rate. Dressings with both properties are thought to have a longer wearing‐time potential, because absorbed fluid can evaporate into the environment (16). In vitro measurements showed that Tielle has a higher total fluid‐handling capacity than other dressing types (8). Thus, the reduced frequency of bandage changes in the present study may contribute to a decrease in the number of dressings needed, thus saving nursing time. As a result, Tielle dressings may also be cost saving. The exact cost effectiveness has to be shown in a dedicated study.

Conclusion

The results of this primary care study indicate that Tielle hydropolymer dressing is a valuable tool in the management of chronic exuding wounds. A great advantage is that Tielle can be useful in a wide range of different wound types. Thus, Tielle provides an effective, safe and possibly cost‐saving dressing in chronic exuding wounds in a primary setting under everyday conditions.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Ethicon GmbH (Johnson & Johnson Medical), Norderstedt, Germany. We thank the participating physicians for their participation in the study. The statistical analysis was done by Metronomia Gesellschaft für statistische Analysen und Beratung GmbH, Munich, Germany.

References

- 1. Atiyeh BS, Ioannovich J, Al‐Amm CA, El‐Musa KA. Management of acute and chronic open wounds: the importance of moist environment in optimal wound healing. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2002; 3: 179–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brem H, Jacobs T, Vileikyte L et al. Wound‐healing protocols for diabetic foot and pressure ulcers. Surg Technol Int 2003;11: 85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seaman S. Dressing selection in chronic wound management. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2002;92: 24–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fletcher J. Managing wound exudate. Nurs Times 2003;99: 51–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vowden K, Vowden P. Understanding exudate management and the role of exudate in the healing process. Br J Community Nurs 2003;8(11 Suppl):4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bishop SM, Walker M, Rogers AA, Chen WY. Importance of moisture balance at the wound‐dressing interface. J Wound Care 2003;12: 125–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schulze HJ, Lane C, Charles H, Ballard K, Hampton S, Moll I. Evaluating a superabsorbent hydropolymer dressing for exuding venous leg ulcers. J Wound Care 2001;10: 511–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Trueman P, Boothman S. TIELLE Plus fluid handling capacity can lead to cost savings. Br J Community Nurs 2003;8(9 Suppl):18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Collier J. A moist, odour‐free environment. A multicentred trial of a foamed gel and a hydrocolloid dressing. Prof Nurse 1992;7: 804–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Finnie A. Hydrocolloids in wound management: pros and cons. Br J Community Nurs 2002; 7: 338–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mallon E, Powell SM. Allergic contact dermatitis from Granuflex hydrocolloid dressing. Contact Dermatitis 1994;30: 110–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sasseville D, Tennstedt D, Lachapelle JM. Allergic contact dermatitis from hydrocolloid dressings. Am J Contact Dermat 1997;8: 236–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sommer S, Wilkinson SM, Peckham D, Wilson C. Type IV hypersensitivity to vitamin K. Contact Dermatitis 2002;46: 94–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thomas S, Banks V, Bale S et al. A comparison of two dressings in the management of chronic wounds. J Wound Care 1997;6: 383–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stewart J. Next generation products for wound management. World Wide Wounds 2002. Retrieved 20 February, 2005 from http://www.worldwidewounds.com

- 16. Carter K. Hydropolymer dressings in the management of wound exudate. Br J Community Nurs 2003;8(9 Suppl): 10–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mellor J, Boothman S. Tielle hydropolymer dressings: wound responsive technology. Br J Community Nurs 2003;8(11 Suppl):14–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. SAS [program]. SAS Institute Inc, 1999.

- 19. Schulze HJ. Clinical evaluation of Tielle Plus dressing in the management of exuding chronic wounds. Br J Community Nurs 2003;8(11 Suppl): 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liew S, Disa J, Cordeiro PG. Nipple‐areolar reconstruction: a different approach to skin graft fixation and dressing. Ann Plast Surg 2001;47: 608–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Taylor A, Lane C, Walsh J, Whittaker S, Ballard K, Young SR. A non‐comparative multi‐centre clinical evaluation of a new hydropolymer adhesive dressing. J Wound Care 1999;8: 489–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maume S, Van De Looverbosch D, Heyman H, Romanelli M, Ciangherotti A, Charpin S. A study to compare a new self‐adherent soft silicone dressing with a self‐adherent polymer dressing in stage II pressure ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage 2003;49: 44–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bolton L, Rijswijk R, Shaffer F. Quality wound care equals cost effective wound care: a clinical model. Adv Wound Care 1997;10: 33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]