Abstract

This prospective, randomised clinical trial compared pain, comfort, exudate management, wound healing and safety with Hydrofiber® dressing with ionic silver (Hydrofiber Ag dressing) and with povidone–iodine gauze for the treatment of open surgical and traumatic wounds. Patients were treated with Hydrofiber Ag dressing or povidone–iodine gauze for up to 2 weeks. Pain severity was measured with a 10‐cm visual analogue scale (VAS). Other parameters were assessed clinically with various scales. Pain VAS scores decreased during dressing removal in both groups, and decreased while the dressing was in place in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group (n = 35) but not in the povidone–iodine gauze group (n = 32). Pain VAS scores were similar between treatment groups. At final evaluation, Hydrofiber Ag dressing was significantly better than povidone–iodine gauze for overall ability to manage pain (P < 0·001), overall comfort (P ≤ 0·001), wound trauma on dressing removal (P = 0·001), exudate handling (P < 0·001) and ease of use (P ≤ 0·001). Rates of complete healing at study completion were 23% for Hydrofiber Ag dressing and 9% for povidone–iodine gauze (P = ns). No adverse events were reported with Hydrofiber Ag dressing; one subject discontinued povidone–iodine gauze due to adverse skin reaction. Hydrofiber Ag dressing supported wound healing and reduced overall pain compared with povidone–iodine gauze in the treatment of open surgical wounds requiring an antimicrobial dressing.

Keywords: Hydrofiber, Hydrofiber Ag dressing, Povidone–iodine gauze, Silver, Surgical wounds

Introduction

Gauze dressings are often the standard of care for open surgical wounds that are left to heal by secondary intent (1). However, removal of gauze may cause trauma and unintentional debridement of newly formed epidermis (2), potentially resulting in pain, tissue injury and exposure of the wound to microorganisms. Gauze dressings also are limited in their ability to handle wound exudate, which leads to erythema and maceration of the surrounding skin (3). Because it provides little protection from infection (4), gauze is often soaked in an antiseptic solution of povidone–iodine before the dressing is applied to the open wound. However, adverse cutaneous reactions have been reported with povidone–iodine dressings, including chemical burns (5), particularly with prolonged exposure, irritation and maceration (6), and contact dermatitis 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. Severe reactions to povidone–iodine may result in ulceration (16).

Several dressings have been developed in recent years to address these limitations of povidone–iodine gauze. Covering an open wound with a dressing that promotes a moist environment may improve healing rates, limit wound‐related pain, better manage exudate and reduce infection rates compared with the use of gauze dressings 17, 18. AQUACEL® Hydrofiber® dressings (ConvaTec, a Bristol‐Myers Squibb company; AQUACEL and Hydrofiber are registered trademarks of E.R. Squibb and Sons, L.L.C.) are designed to promote a moist environment for wound healing. They are composed entirely of sodium carboxymethylcellulose fibres that absorb and retain wound exudate and microorganisms, immobilising them in the dressing (19). Controlled studies of Hydrofiber dressings in patients with open surgical wounds suggest that they are easy to use and are associated with little or no pain on removal 20, 21. By reducing the number of dressing changes required and facilitating earlier discharge from the hospital compared with gauze dressings, the use of Hydrofiber dressings on open surgical wounds may reduce the total cost of postoperative care compared with gauze dressings (22).

Hydrofiber® dressing with ionic silver (Hydrofiber Ag dressing) contains 1·2% ionic silver and has antimicrobial activity in vitro lasting for up to 14 days (23). It was hypothesised that Hydrofiber Ag dressing would be easy to use and would reduce wound pain, improve patient comfort, improve exudate handling and promote wound healing compared with traditional wound care with povidone–iodine gauze. The objective of this study was to evaluate these efficacy endpoints and the safety of Hydrofiber Ag and povidone–iodine gauze dressings in patients with open surgical or traumatic wounds.

Patients and methods

Study design

This was a prospective, randomised, open‐label, active‐controlled, phase III study that was performed at seven sites in Germany, France and Great Britain between May 2003 and April 2004. Adults of legal consenting age were eligible for the study if they had an open surgical wound (e.g., dehisced wound, surgically reopened wound, incised and drained abscess) or an open traumatic wound left to heal by secondary intent and requiring an antimicrobial dressing. Exclusion criteria included a narrow sinus from which dressing removal would be difficult, a wound that was opened more than 24 hours before study entry, history of poor compliance with medical treatments, participation in a clinical trial within the previous 12 weeks, known sensitivity to either study treatment, thyroid disorders, use of lithium therapy, impaired renal function and pregnancy. All subjects provided informed written consent to participate. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the appropriate institutional review board or ethics committee for each study site.

Subjects were randomly assigned to treatment with Hydrofiber Ag dressing or povidone–iodine gauze. The randomisation scheme was created before the study using SAS 8·1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and subjects were assigned to study treatment in sequential order using sealed randomisation envelopes. All study treatment was administered without concealment. Dressings were changed as clinically indicated (at least once every 7 days for Hydrofiber Ag dressing, and as clinically indicated for povidone–iodine gauze) and were used until complete healing of the wound occurred, or for up to 2 weeks. Study dressings could be changed in the clinic or at home. If necessary, to facilitate removal, dressings were soaked in saline for at least 15 minutes. For the purpose of comparison, the Hydrofiber Ag and povidone–iodine gauze dressings were collectively referred to as ‘study dressings’, whereas dressings that were applied when the wound was opened, but before the subject enrolled in the study, were referred to collectively as ‘prestudy dressings’.

Outcome measures

Efficacy and safety outcomes were recorded whenever the investigator examined the wound, at least once every 7 days. The primary efficacy endpoint of the study was pain severity reported by the subject during dressing applications, removals and while in place, as measured by a visual analogue scale (VAS). Pain VAS was recorded using the Johns Hopkins Pain Rating Instrument, a validated instrument for the measurement of pain in burned patients (24). A moveable, 10‐cm‐long plastic strip was labelled on one side with ‘No Pain’ at the far left and ‘Worst Pain Imaginable’ at the far right. The administrator of the test slid the strip until the subject instructed him/her to stop and then measured the severity of pain using the gauge printed on the reverse side of the scale. At baseline and weekly study visits, pain scores on the VAS were recorded with the old dressing in place and during removal, as well as during application of the new dressing.

Secondary efficacy measures included investigator ratings of wound comfort, bleeding, exudate handling and trauma on removal; change in wound appearance and size; wound infection; the need for debridement; and the ease of use for each treatment. Wound size was calculated as the product of wound length × wound width. Wound depth was measured with a sterile cotton‐tipped applicator. Clinical signs suggesting infection included warmth, redness, increased tenderness, swelling, increased exudate levels or purulent discharge and malodour. Safety measures included all reported adverse events. For each in‐clinic dressing change, the investigator rated trauma on dressing removal (none, minimal, moderate or excessive), wound bleeding on dressing removal (none, minimal, moderate or excessive), exudate (none, minimal, moderate or heavy), appearance of the surrounding skin (normal, erythema, maceration or other), presence or absence of infection, method of debridement (on ward, in surgical theatre, other or none), analgesics used for debridement, the ease of dressing application (very easy, easy, difficult very difficult) and any adverse events. A dressing change evaluation was to be completed for all in‐clinic dressing changes, including removal of the final dressing.

At the initial and final visits, the investigator recorded the appearance of the wound bed (proportion with epithelium, granulation, slough, eschar and other). At the final visit, the investigator recorded final wound dimensions, overall improvement or deterioration of the wound, overall impressions of the dressing at the final visit (excellent, good, fair or poor) with regard to pain management, comfort in place, comfort on removal, exudate management, ease of application and ease of removal.

Statistical analysis

The sample size for the study was determined to be 65 subjects based on the findings of a controlled clinical study of Hydrofiber dressing without silver (22). If the true treatment difference in mean pain score was approximately two‐thirds of the inherent subject‐to‐subject variation, a total of 52 evaluable subjects (26 per group) would assure 80% power for the statistical test at the 5% level of significance. Enrolment of 65 subjects allowed for 20% dropout before study completion.

All analyses were performed with SAS 8·1. Efficacy analyses were performed on the intent‐to‐treat population, which included subjects who had at least one complete dressing change. Safety analyses included subjects who were treated with the study dressing at least once. The primary null hypothesis was that there was no statistically significant difference in pain scores between the treatments, and the alternate hypothesis was that mean pain scores would be lower in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group than in the povidone–iodine group.

Efficacy data were analysed for the visits at baseline, Day 7 and Day 14. Data for categorical variables were summarised by appropriate contingency tables and the results from either Fisher’s exact test or the Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel (CMH) test controlling for pooled study centre. Data for ordinal categorical variables were analysed using the CMH (row mean scores) test with the rank values (modified ridit analysis). The effects of treatment, patient and wound characteristics on the primary outcome were assessed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) modelling. The General Linear Model procedure was used to assess the influence of pain medication use on the primary efficacy endpoint.

Results

Subject disposition

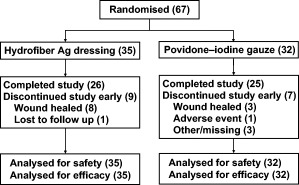

Subjects were recruited at three centres in Great Britain (n = 3, 7 and 9), one centre in Germany (n = 4) and three centres in France (n = 4, 30 and 10). Of the 67 subjects randomly assigned to treatment, 26 of 35 (74·3%) in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and 25 of 32 (78·1%) in the povidone–iodine gauze group continued treatment through the end of the 2‐week study period (Figure 1). In the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group, eight (22·9%) subjects were able to stop treatment before the end of the study due to full wound healing, and one (2·9%) subject was lost to follow up. In the povidone–iodine gauze group, reasons for early discontinuation included wound healing for three (9·4%) subjects, adverse event for one (3·1%) subject and other unclassified reasons for three (9·4%) subjects.

Figure 1.

Subject disposition.

Baseline and treatment characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study subjects were comparable between the treatment groups at baseline (Table 1). Wounds included pilonidal cyst, abscess (cervical, back, axilla, gluteal, scrotum or groin), open fracture [lower leg or ankle), laparotomy, posthernia repair and stomal closure (ileostomy)]. Wound size varied greatly between subjects, and the average wound size in the povidone–iodine gauze group was numerically higher than that in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group. It appears that this difference was primarily due to outlier values (e.g., a wound size of 15 200 mm2 in the povidone–iodine gauze group). However, median values, which are often considered better markers for treatment group comparison when extreme outliers exist (25), for wound size were 600 mm2 in both treatment groups. Nine (25·7%) subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and 11 (34·4%) in the povidone–iodine gauze group had moderate to heavy wound exudate at baseline. The appearance of the skin surrounding the wound was comparable overall between treatment groups and was normal for 24 (68·6%) subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and 21 (65·6%) subjects in the povidone–iodine gauze group.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline

| Characteristic | Hydrofiber dressing with ionic silver (n = 35) | Povidone–iodine gauze (n = 32) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (range) | 34 (17–67) | 43 (20–77) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 23 (65·7) | 23 (71·9) |

| Female | 12 (34·3) | 9 (28·1) |

| Current dressing, n (%)* | ||

| Gauze | 19 (54·3) | 20 (62·5) |

| Hydrofiber (without silver) | 8 (22·9) | 3 (9·4) |

| Alginate | 2 (5·7) | 1 (3·1) |

| Foam | 2 (5·7) | 1 (3·1) |

| Other | 5 (14·3) | 5 (15·6) |

| None | 8 (22·9) | 7 (21·9) |

| Wound duration, (hours), mean (range) | 11 (0–22) | 10 (0–24) |

| Wound exudate, n (%) | ||

| None | 7 (20·0) | 3 (9·4) |

| Minimal | 19 (54·3) | 18 (56·3) |

| Moderate | 7 (20·0) | 9 (28·1) |

| Heavy | 2 (5·7) | 2 (6·3) |

| Wound area (mm2) | ||

| Mean | 976 | 1463 |

| Median | 600 | 600 |

| Range | 40–4050 | 24–15 200 |

| Wound composition (%), mean | ||

| Epithelium | 13 | 7 |

| Granulation | 20 | 18 |

| Slough | 11 | 9 |

| Eschar | <1 | 4 |

| Other | 56 | 62 |

| Surrounding skin, n (%)† | ||

| Normal | 24 (68·6) | 21 (65·6) |

| Erythema | 10 (28·6) | 10 (31·3) |

| Maceration | 1 (2·9) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 2 (6·3) |

| Antibiotic use at baseline, n (%) | 7 (20·0) | 7 (21·9) |

Total for current dressing at baseline adds to more than 100% because more than one type of dressing could be used.

More than one category could be selected for each subject.

The wounds had been open a mean (range) of 11 (0–22) hours before the first application of Hydrofiber Ag dressing and 10 (0–24) hours before the first application of povidone–iodine gauze. Most wounds (54·3% in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and 62·5% in the povidone–iodine gauze group) were covered with gauze prior to study treatment. Use of Hydrofiber dressings without ionic silver before baseline tended to be more common in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group than in the povidone–iodine gauze group (22·9% versus 9·4%). A comparable proportion of subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group (22·9%) and the povidone–iodine gauze group (21·9%) did not have a dressing in place at baseline. Seven subjects in each group (20·0% Hydrofiber Ag dressing and 21·9% povidone–iodine gauze) received antibiotics at baseline.

Median total duration of study treatment was 15 days in both treatment groups. Study dressings were most commonly changed at home. The median duration of use for both dressings was 1 day (range, 0–7 days), and the mean number of dressing changes was comparable between the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group (11·0) and the povidone–iodine gauze group (10·7). Analgesics and antipyretics were the most commonly used concomitant medications in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group (37·1%) and the povidone–iodine gauze group (34·4%) (Table 2). Use of analgesics varied between study sites: few subjects at the two centres that enrolled the most participants received analgesics, whereas almost all the subjects at the remaining sites received analgesics. At the final visit, subjects who received pain medication tended to report lower pain scores with the study dressing in place than the subjects who did not receive pain medication (P = ns, ANCOVA). Other commonly used medications were consistent with postsurgical medical care and included antibiotics or antibacterials; antiemetics; and antithrombotics, anticoagulants or fibrinolytics.

Table 2.

Concomitant treatments, n (%)

| Concomitant treatment | Hydrofiber dressing with ionic silver (n = 35) | Povidone–iodine gauze (n = 32) |

|---|---|---|

| Analgesic/antipyretic | 13 (37·1) | 11 (34·4) |

| Antibiotic/antibacterial | 6 (17·1) | 8 (25·0) |

| Antiemetic | 4 (11·4) | 0 (0) |

| Anticoagulant/antithrombotic/fibrinolytic | 3 (8·6) | 1 (3·1) |

| Antihypertensive | 2 (5·7) | 2 (6·3) |

Pain

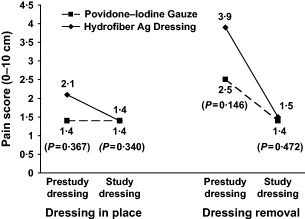

Prior to starting study treatment, wound pain was not significantly different between groups according to VAS, although it tended to be higher in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group than in the povidone–iodine gauze group when the prestudy dressing was in place (2·1 versus 1·4 cm, P = ns, CMH) and when it was removed (3·9 versus 2·5 cm, P = ns, CMH) (Figure 2). Mean pain scores were identical between the Hydrofiber Ag dressing and povidone–iodine gauze groups while the first dressing was in place (1·4 versus 1·4 cm, P = ns, CMH), and they were nearly the same when the first dressing was removed (1·5 versus 1·4 cm, P = ns, CMH). Pain scores were not recorded during application of the prestudy dressing, but the mean pain score was 2·6 cm for the first application of Hydrofiber Ag dressing and 2·1 cm for povidone–iodine gauze (P = ns, CMH).

Figure 2.

Mean pain scores on a 10‐cm visual analogue scale with the prestudy dressing and the study dressing in the Hydrofiber dressing with ionic silver group (solid line) and the povidone–iodine gauze group (dashed line).

Data were collected for only four subjects at the 2‐week final visit; a dressing change evaluation form was not completed at the final visit for the remaining subjects. Consequently, analyses of changes in pain using the VAS were limited to the change from baseline to Week 1. The decrease in mean pain score from baseline was numerically greater in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group than in the povidone–iodine gauze group, when the dressing was in place (−0·7 versus −0·0 cm) and during removal (−2·4 versus −1·1 cm).

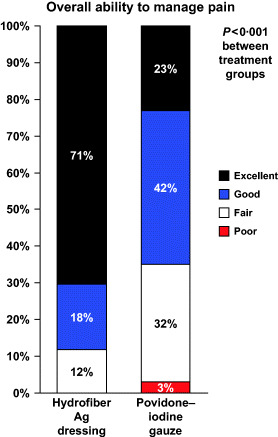

At the final visit (at healing or at Week 2), pain management was rated better overall for subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group than in the povidone–iodine gauze group (P < 0·001, CMH) (Figure 3). Overall pain management was rated as ‘excellent’ by 24 (70·6%) subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and seven (22·6%) subjects in the povidone–iodine gauze group.

Figure 3.

Overall ability of the study dressing to manage wound pain.

Comfort

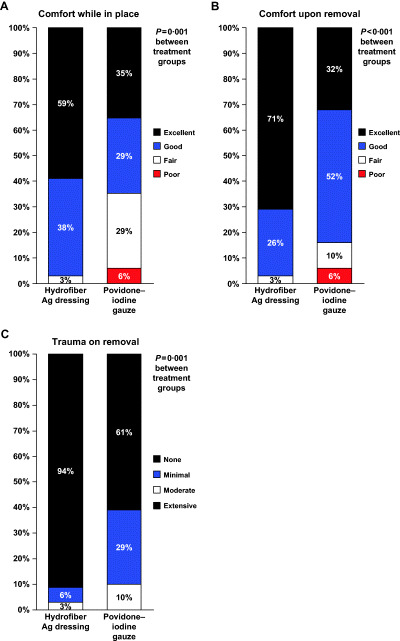

Comfort ratings at the final visit were also significantly better for Hydrofiber Ag dressing than for povidone–iodine gauze while the dressing was in place (P = 0·001, CMH) and during removal (P < 0·001, CMH). The comfort of the dressing while in place was rated as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ overall for 97·1% of subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and for 64·5% of subjects in the povidone–iodine gauze group (Figure 4A). Comfort of dressing removals was rated as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ overall for 97·1% of subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and for 83·9% of subjects in the povidone–iodine gauze group (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Comfort and trauma scores at the final visit. (A) Comfort with the study dressing in place. (B) Comfort during removal of the study dressing. (C) Wound trauma during removal of the study dressing.

Trauma on dressing removal

Hydrofiber Ag dressing was associated with significantly less trauma to the wound on dressing removal than povidone–iodine gauze (P < 0·001, CMH) (Figure 4C). No trauma on dressing removal was reported at the final visit for 94·3% of the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and for 61·3% of the povidone–iodine gauze group. No subject in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group had moderate or severe trauma when the study dressing was removed at the last visit. Three (9·7%) subjects in the povidone–iodine gauze group had moderate trauma at the final visit. Consistent with these findings, more subjects had no bleeding during dressing changes in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group than in the povidone–iodine gauze group (88·6% versus 64·5%, P < 0·05, CMH). The four cases of bleeding during dressing changes in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group were all minor; in the povidone–iodine group, one subject had moderate bleeding and ten subjects had minor bleeding during dressing changes.

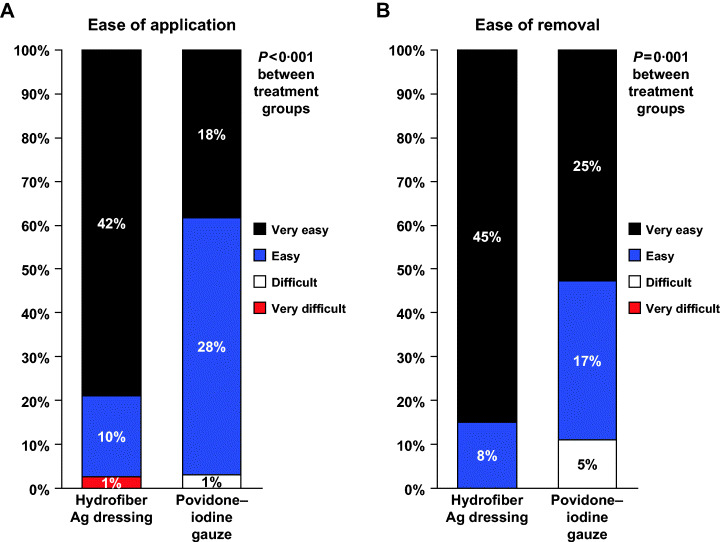

Ease of use

Investigators reported that Hydrofiber Ag dressing was significantly easier to apply (P < 0·001, CMH) and significantly easier to remove (P = 0·001, CMH) than the povidone–iodine gauze. Thirty of 38 (78·9%) Hydrofiber Ag dressing applications in the clinic and 13 of 34 (38·2%) povidone–iodine gauze applications in the clinic were rated as ‘very easy’ to apply (Figure 5A). Thirty‐four of 40 (85·0%) Hydrofiber Ag dressing removals in the clinic and 19 of 36 (52·8%) povidone–iodine gauze removals in the clinic were rated as ‘very easy’ to remove (Figure 5B). Few subjects required the dressing to be soaked in saline to assist with removal in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing (8·6%) or the povidone–iodine (12·9%) group.

Figure 5.

Ease‐of‐use scores. (A) Ease of application during 38 dressing changes in the Hydrofiber dressing with ionic silver (Hydrofiber Ag dressing) group and 24 dressing changes in the povidone–iodine gauze group. (B) Ease of removal during 40 dressing changes in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and 36 dressing changes in the povidone–iodine gauze group.

Wound healing

Several measures of wound healing numerically favoured Hydrofiber Ag dressing over povidone–iodine gauze (Table 3). More subjects healed at the completion of treatment in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group than in the povidone–iodine gauze group (23% versus 9%), but the difference was not statistically significant. Complete healing or marked improvement was reported for 91·2% of the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and for 74·2% of the povidone–iodine gauze group. Mean time to healing was similar between the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and the povidone–iodine gauze group (14·1 versus 13·9 days, P = ns, log‐rank test).

Table 3.

Wound outcomes during study

| Hydrofiber dressing with ionic silver (n = 34) | Povidone–iodine gauze (n = 31) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Final wound appearance (%), mean | |||

| Epithelium | 42·2 | 31·2 | |

| Granulation | 49·7 | 56·1 | |

| Slough | 6·3 | 7·4 | |

| Eschar | 0·7 | 0·7 | |

| Other | 1·0 | 4·7 | |

| Time to healing (days), mean | 14·1 | 13·9 | ns |

| Overall management of exudate, n (%) | <0·001 | ||

| Excellent | 14 (41·2) | 7 (22·6) | |

| Good | 18 (52·9) | 9 (29·0) | |

| Fair | 2 (5·9) | 9 (29·0) | |

| Poor | 0 (0) | 6 (19·4) | |

Wound size decreased significantly from baseline in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group (adjusted mean −551 mm2, P < 0·01 versus baseline, t‐test) and the povidone–iodine gauze group (−401 mm2, P < 0·05 versus baseline, t‐test), but the changes were not significantly different between groups (P = ns, ANCOVA). The adjusted mean changes for wound depth were significant (P < 0·001 versus baseline, t‐test) in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group (−9·0 mm) and the povidone–iodine gauze group (−10·0 mm), but the improvements were not significantly different between treatment groups (P = ns, ANCOVA). Characteristics of the wound bed appearance at the final visit were similar between treatment groups, but epithelialised tissue tended to be present more often in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group than in the povidone–iodine group (42·2% versus 31·2%).

Exudate management

Exudate management in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group was statistically superior to that in the povidone–iodine gauze group (P < 0·001, CMH); 94% and 52% of subjects in each group, respectively, had ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ management of wound exudate overall (Table 3). Debridement was only performed on two wounds after baseline (one subject in each group), so statistical comparisons were not performed for debridement methods and the use of analgesics for debridement.

Infection

At baseline, 16 (45·7%) subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and 20 (62·5%) subjects in the povidone–iodine gauze group had infected wounds (P = ns, CMH). During study treatment, four (11·4%) subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group and four (12·5%) subjects in the povidone–iodine gauze group had infected wounds (P = ns, CMH).

Safety of study treatment

No adverse events were reported in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group. Three subjects (9%) in the povidone–iodine gauze group had adverse events, all at the wound site. One subject with an adverse event discontinued treatment early due to an allergic reaction of moderate severity, with redness, severe secretion and itching, that was considered probably related to povidone–iodine. Another subject in the povidone–iodine gauze group had skin burn of moderate severity that was identified at the final study visit and was believed to be related to povidone–iodine. The third subject continued treatment with povidone–iodine gauze when mild local haemorrhage unrelated to study treatment occurred at the wound site.

Discussion

In this prospective, randomised, open‐label, phase III study, treatment of open surgical and traumatic wounds with Hydrofiber Ag dressings was superior to treatment with povidone–iodine gauze with respect to wound pain, comfort, trauma on dressing removal, exudate management and ease of use. Mean VAS scores during dressing removal decreased by 62% (from 3·9 at baseline to 1·5 at the end of treatment) and 44% (from 2·5 to 1·4) in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing and povidone–iodine groups, respectively, compared with the prestudy dressings. Mean scores for pain with the dressing in place decreased by 33% (from 2·1 to 1·4 cm) and 0% (from 1·4 to 1·4 cm) in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing and povidone–iodine gauze groups, respectively.

Less pain and improved comfort overall was reported at the final assessment (healing or 2 weeks) for significantly more subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group than in the povidone–iodine gauze group. Dressing comfort was reported as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ overall for all but one subject in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group, both during removal and while the dressings were in place. These findings are consistent with published literature reporting less pain with the same Hydrofiber dressing without silver compared with gauze dressings in surgical wounds (22) or compared with alginate dressings in chronic leg ulcers (26).

Previous studies of patients with acute pain in emergency departments reported that the minimal clinically important improvement in pain ranged from 0·9 to 3·0 cm, using a 10‐cm VAS 27, 28 [these studies used pain VAS tools other than the Johns Hopkins Pain Rating Instrument used in this study (24)]. However, another study of patients with neuropathic pain noted that a 30% reduction in pain severity may be a more reliable measure of clinically important pain relief than the actual change in the score, particularly when the scores at baseline are low (29). Furthermore, a study of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain reported that those patients with at least slight response to treatment had greater absolute and percentage reductions in pain severity on a scale from 0 to 10 if they had severe pain at baseline (7 points or more) than if they reported milder pain at baseline (less than 4 points) (30).

It is likely, therefore, that the low pain scores at baseline in the present study (over 50% of subjects had VAS scores less than 2 of 10 cm at baseline) reduced the ability of the study to demonstrate a significant treatment difference in absolute subject‐rated pain scores. Analgesic therapy was widespread in both treatment groups, and the use of analgesics tended to influence VAS scores. Prohibiting the use of analgesics before pain assessments at baseline and at clinic visits in this study might have enhanced the ability to detect significant differences between treatment groups in the primary endpoint of pain during dressing changes. Restricting the use of analgesics between study visits could have increased pain scores between dressing changes, possibly influencing the separation between the study treatment and the control group, but denying pain medication to patients with open wounds to intentionally increase pain scores would be unethical.

Hydrofiber Ag dressing was associated with lower trauma scores on dressing removal and was found to be easier to apply and remove than povidone–iodine gauze. Greater ease of application was expected because the gauze needed to be soaked thoroughly with the povidone–iodine mixture before it could be applied to the wound, whereas Hydrofiber Ag dressing was simply applied to the wound without additional preparation required. Greater ease of removal and reduced trauma to the wound on dressing removal were consistent with the fact that Hydrofiber Ag dressing is designed to maintain a moist environment to prevent adherence to the wound, while povidone–iodine gauze is typically used for wet‐to‐dry dressings that may require greater effort for removal.

Several wound healing outcomes favoured Hydrofiber Ag dressing over povidone–iodine gauze, either significantly or numerically. Wound size and depth decreased from baseline in both treatment groups, but these changes were not significantly different between treatment groups. Using subjective measures of wound healing, investigators reported that subjects in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group were (23%) more likely than subjects in the povidone–iodine gauze group (9%) to achieve complete healing within 2 weeks of treatment. In the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group, wounds were reported to be healed in approximately one‐quarter of subjects before study treatment was complete, and investigators reported that wounds demonstrated marked improvement for another 71% of subjects. In the povidone–iodine gauze group, investigators tended to report less substantial improvement in wound condition. Investigators rated overall management of wound exudate as significantly better with Hydrofiber Ag dressing than with povidone–iodine gauze, with reports of excellent exudate management for 41% and 23% of subjects, respectively. This advantage of Hydrofiber Ag dressing was likely attributable to the fluid‐handling properties of the Hydrofiber dressing.

Both dressings were changed an average of once daily in this study. Daily dressing changes enable the clinician to assess wound healing, condition of the surrounding skin, exudate handling and the presence of infection on a daily basis. However, Hydrofiber dressings can be changed up to every 7 days, thereby improving the convenience and potentially reducing the frequency of interventions required compared with changing gauze at least once daily. With greater clinical experience outside of a clinical study, physicians and nurses may choose to extend the wear time of Hydrofiber Ag dressing in surgical wounds.

No adverse events were reported in the Hydrofiber Ag dressing group. One subject in the povidone–iodine gauze group had treatment‐related adverse events at the wound site, leading to study discontinuation, one had moderate skin burn and the other had a moderate allergic reaction. Chemical burns 5, 6 and allergic reactions 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 have both been reported previously with the use of povidone–iodine. In severe cases, skin ulceration may occur (16), so careful evaluation for skin reactions is appropriate whenever povidone–iodine gauze is used. Infection rates were similar for the two antimicrobial treatments.

The major limitation of this study was the observed variation in pain assessment and pain medication use by study site. A dressing change evaluation form was not completed for many subjects at the final dressing change, and evaluations of pain and several of the secondary study outcomes were only conducted at baseline and 7 days for most subjects. Consequently, the short duration of follow up may not have provided enough time for the pain scores to decrease significantly. Supporting this concept is the fact that pain scores with the Johns Hopkins Pain Rating Instrument at Week 1 were not significantly different between treatment groups, but overall assessments of pain intensity at Week 2 were significantly better for Hydrofiber Ag dressing than for povidone–iodine gauze.

The lack of blinding was another potential limitation of this study. Neither the subjects nor the investigators were blinded to study treatment when assessing safety and efficacy. Future studies might benefit from the use of independent assessors who are blinded to study treatment allocation. The study also used povidone–iodine gauze as the comparator group because it is commonly used in the management of open surgical wounds. Comparative evaluations of newer moisture‐retentive dressings would also be informative to establish their relative clinical roles in the management of these wounds.

In this study, Hydrofiber Ag dressing was associated with better management of pain, less trauma, greater comfort and ease of use and better exudate handling, with at least as good wound healing as with standard care with povidone–iodine gauze. These results provide preliminary evidence supporting the use of Hydrofiber Ag dressing as an alternative to povidone–iodine gauze to promote wound healing and to provide antimicrobial activity in the treatment of open surgical and traumatic wounds left to heal by secondary intent. Additional studies of Hydrofiber Ag dressing in similar settings are warranted to address some of the acknowledged limitations of this exploratory study.

Acknowledgements

The AQUACEL Ag Surgical/Trauma Wound Study Group included: Philip Drew, Aswatha Ramesh and Elaine Gullaksen of Castle Hill Hospital, Cottingham Hull, England; Theodor Offori and Zorica Vujovic of Barnsley District General Hospital, Barnsley, England; Alison Johnstone of Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Glasgow, Scotland; Dirk A. Hollander of University Hospital of the RWTH Aachen, Aachen, Germany; Jean‐Edouard Clotteau of Clinique de la porte de Pantin, Paris, France; Florent Jurczak of Polyclinique de l’Océan, Saint Nazaire, France; and Thierry Dugré of Centre Hospitalier Camille Guerin, Chatellerault, France. The study was supported by a grant from ConvaTec, a Bristol‐Myers Squibb Company, which manufactures and markets AQUACEL® Ag Hydrofiber® dressing with Silver. ConvaTec monitored the study design, study conduct and data collection, and supervised data analysis and the preparation of the manuscript.

This study has not been published in full previously. Portions of this material were presented at the 18th Annual Symposium on Advanced Wound Care (2005); the 37th Annual Meeting of the Wound Ostomy & Continence Nurses Society (2005); the STUTTGART2005 Meeting of the European Tissue Repair Society, the European Wound Management Association and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Wundheilung und Wundbehandlung e.V. (2005); and the 10th Conférence Nationale des Plaies et Cicatrisations (2006).

References

- 1. Pieper B, Templin TN, Dobal M, Jacox A. Wound prevalence, types, and treatments in home care. Adv Wound Care 1999;12:117–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alvarez OM, Mertz PM, Eaglstein WH. The effect of occlusive dressings on collagen synthesis and re‐epithelialization in superficial wounds. J Surg Res 1983;35:142–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. White RJ, Cutting KF. Interventions to avoid maceration of the skin and wound bed. Br J Nurs 2003;12:1186–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lawrence JC. Dressings and wound infection. Am J Surg 1994;167:21S–4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corazza M, Bulciolu G, Spisani L, Virgili A. Chemical burns following irritant contact with povidone‐iodine. Contact Dermatitis 1997;36:115–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nahlieli O, Baruchin AM, Levi D, Shapira Y, Yoffe B. Povidone‐iodine related burns. Burns 2001;27:185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marks JG Jr. Allergic contact dermatitis to povidone‐iodine. J Am Acad Dermatol 1982;6:473–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lachapelle JM. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis to povidone‐iodine. Contact Dermatitis 1984;11:189–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ancona A, Suarez de la Torre R, Macotela E. Allergic contact dermatitis from povidone‐iodine. Contact Dermatitis 1985;13:66–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kudo H, Takahashi K, Suzuki Y, Tanaka T, Miyachi Y, Imamura S. Contact dermatitis from a compound mixture of sugar and povidone‐iodine. Contact Dermatitis 1988;18:155–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Van Ketel WG, Van Den Berg WH. Sensitization to povidone‐iodine. Dermatol Clin 1990;8:107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tosti A, Vincenzi C, Bardazzi F, Mariani R. Allergic contact dermatitis due to povidone‐iodine. Contact Dermatitis 1990;23:197–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Erdmann S, Hertl M, Merk HF. Allergic contact dermatitis from povidone‐iodine. Contact Dermatitis 1999;40:331–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nishioka K, Seguchi T, Yasuno H, Yamamoto T, Tominaga K. The results of ingredient patch testing in contact dermatitis elicited by povidone‐iodine preparations. Contact Dermatitis 2000;42:90–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iijima S, Kuramochi M. Investigation of irritant skin reaction by 10% povidone‐iodine solution after surgery. Dermatology 2002;204 Suppl. 1:103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mochida K, Hisa T, Yasunaga C, Nishimura T, Nakagawa K, Hamada T. Skin ulceration due to povidone‐iodine. Contact Dermatitis 1995;33:61–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kerstein MD, Gemmen E, VanRijswijk L, Lyder CH, Phillips T, Xakellis G, Golden K, Harrington C. Cost and cost effectiveness of venous and pressure ulcer protocols of care. Dis Manag Health Outcomes 2001;9:651–63. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vermeulen H, Ubbink D, Goossens A, De Vos R, Legemate D. Dressings and topical agents for surgical wounds healing by secondary intention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004:CD003554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walker M, Hobot JA, Newman GR, Bowler PG. Scanning electron microscopic examination of bacterial immobilisation in a carboxymethyl cellulose (AQUACEL) and alginate dressings. Biomaterials 2003;24:883–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Foster L, Moore P. The application of a cellulose‐based fibre dressing in surgical wounds. J Wound Care 1997;6:469–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Foster L, Moore P, Clark S. A comparison of hydrofibre and alginate dressings on open acute surgical wounds. J Wound Care 2000;9:442–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moore PJ, Foster L. Cost benefits of two dressings in the management of surgical wounds. Br J Nurs 2000;9:1128–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bowler PG, Jones SA, Walker M, Parsons D. Microbicidal properties of a silver‐containing hydrofiber dressing against a variety of burn wound pathogens. J Burn Care Rehabil 2004;25:192–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choinière M, Auger FA, Latarjet J. Visual analogue thermometer: a valid and useful instrument for measuring pain in burned patients. Burns 1994;20:229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Le CT. Introductory biostatistics. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harding KG, Price P, Robinson B, Thomas S, Hofman D. Cost and dressing evaluation of hydrofiber and alginate dressings in the management of community‐based patients with chronic leg ulceration. Wounds 2001;13:229–36. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kelly AM. Does the clinically significant difference in visual analog scale pain scores vary with gender, age, or cause of pain? Acad Emerg Med 1998;5:1086–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee JS, Hobden E, Stiell IG, Wells GA. Clinically important change in the visual analog scale after adequate pain control. Acad Emerg Med 2003;10:1128–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11‐point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001;94:149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri CA, Ciapetti A, Grassi W. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain 2004;8:283–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]