Abstract

A model of infected skin ulceration could prove useful in assessing the clinical effectiveness of antimicrobial ointments and dressings. However, no such models have been previously established. Three types of wound were induced in rats: full‐thickness wounds covered with gauze, burn wounds and wounds resulting from mechanical trauma. Wounds were inoculated with S. aureus or P. aeruginosa. Persistent infected wounds were observed only in full‐thickness wounds covered with gauze. In a second experiment, colonies of P. aeruginosa or S. aureus were counted within 15 × 15 mm full‐thickness wounds covered with gauze. Wounds were inoculated with 1·0 × 106 colony‐forming units (CFU) of P. aeruginosa or S. aureus and then sealed to ensure an enclosed environment. Tissue bacterial counts exceeded 106 CFU/g from the next day until day 9 after infection. Bacterial counts exceeded 108 CFU/ml in wound exudate collected between days 1 and 7. We have developed a model of wound infection in which persistence of infection can be achieved for 9 days following ulceration due to the application of gauze to the base of a full‐thickness wound.

Keywords: Animal model, Colonisation, Rat, S. aureus, Wound infection

Introduction

Skin ulceration is a serious clinical complication of surgical wound infections, atherosclerotic disease, venous stasis and diabetes mellitus and occurs with decubitus ulcers (1). Infection of skin ulcers may necessitate hospitalisation or even amputation, as may occur with diabetic foot disease, posing significant morbidity and expense (1). Although systemic antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment for infected wounds, debate surrounds the concurrent use of topical antimicrobial ointments or dressings 2, 3, 4). To investigate the role of antimicrobial ointments and dressings in the treatment of infected chronic ulcers, a robust animal model that closely mimics clinical infection is needed. However, no animal models have been established to date. Rats, mice and other rodents are convenient for handling; however, it is difficult to induce chronic ulcers in these animals because full‐thickness wounds on their backs tend to heal naturally in most cases, even following inoculation with bacteria (5, 6). To prepare infected wounds surgically, researchers have attempted dermal injury, including burns (7) and crush wounds (8, 9), in combination with the introduction of foreign bodies, such as sutures (10, 11), sand (12) or dextran beads (13, 14). These models have been used primarily to investigate the effects of antibiotics on mortality rates, and ulceration as a result of chronic infection has not been established in these models (7, 11, 14, 15). There is also a significant amount of research surrounding burn infections. Infected burn wounds can be prepared by injecting bacteria under the scab of the burn wound or by applying bacteria to the burn site. Again, these models have been used primarily to determine the therapeutic effect of systemic antibiotics or the development of shock (6, 13, 16), and no reliable models of burn wound ulceration have been developed to date. Furthermore, in studies where bacterial counts were taken, high levels of bacteria were not observed 3 days after inoculation (17). Necrosis of skin was not observed in these studies, nor was it observed in the present studies following inoculation of bacteria into a burn wound.

Other surgical models of infected wounds into which foreign bodies have been implanted exist [e.g. sutures, sand, dextran beads and Teflon tubes (18)]. However, suturing of the wounds in these models has prevented ulcer formation. Numerous models involving crushed wound margins have been investigated, although these are only useful in preparing subcutaneous abscesses and are not associated with skin ulceration (8, 9).

Thus, we investigated the development of an animal model of skin injury in which persistence of infection could be achieved by applying gauze to a full‐thickness wound or by suspending bacteria with dextran beads before inoculation.

Materials and methods

The following materials were used in this study: polyurethane film (3M Corporation, St Paul, MN, USA), Eakin seals (ConvaTec, Skillman, NJ, USA), dextran beads, phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma Chemicals, St Louis, MO, USA), brain–heart infusion, tryptic soy agar (TSA) (BHI, Difco, Detroit, MI, USA), sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal, Dainippon Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan), P. aeruginosa 5142rif (serotype E, nonmucoid), S. aureus (clinical isolate MSSA number 7743114), male Sprague– Dawley rats (Saitama Experimental Animals Supply, Sugito, Saitama, Japan) and 100% woven cotton gauze (Osaki Medical, Nagoya, Japan).

Suspensions of both P. aeruginosa and S. aureus were prepared as described below. Nonmucoid P. aeruginosa was kindly donated by Dr Ikeda of the Department of Bacteriology at Teikyo University School of Medicine. Methicillin‐susceptible S. aureus was a clinical isolate obtained from an infected surgical wound in an orthopaedic surgery patient. Each bacterium was grown on TSA overnight, after which individual colonies were inoculated into BHI and incubated for 12 hours at 35°C. The cultured cells were centrifuged three times in PBS at 980 g and were then suspended in PBS at a concentration of approximately 0·5 × 108 colony‐forming units (CFU)/ml. After the suspensions were vortexed, colony counts were taken by measuring the absorbance at 600 A. The mixtures of dextran beads and bacteria were prepared according to the method of Bunce et al. (5). Dextran beads were suspended in PBS at a concentration of 1 g per 50 ml and were then autoclaved to produce a stock solution. An aliquot (0·02 ml) of this stock solution was mixed with 0·5 ml of PBS with or without bacteria, after which BHI broth was added to bring the final volume to 1 ml.

Male Sprague–Dawley rats aged 6 weeks were used in this study. Rats were anaesthetised by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg), after which the hair on their backs was removed with clippers, and their skin was sterilised with povidone iodine. In the first experiment, 10 rats were assigned to each of the following experimental groups. Wounds were examined daily after inoculation with bacteria, and the appearance of any exudate was recorded. All animals were given drinking water containing acetaminophen at a concentration of 0·25 mg/ml.

Group 1

Two 15 × 15 mm full‐thickness wounds penetrating the dartos fascia were prepared on the back of each rat, equidistant from the vertebral column. Gauze that had been soaked in a 5000‐fold dilution of adrenaline in physiological saline was placed on the wound surface to provoke haemostasis. Bacterial suspension (0·5 ml) containing dextran beads was inoculated onto the ulcer surface, or a 15 × 15 mm piece of gauze (7·4 mg) was placed on the base of the wound, after which the gauze was soaked with a bacterial suspension at a concentration of 1·5 × 106 CFU/wound. As a control, bacterial suspension without dextran beads was placed on the base of the ulcer in one group. The periphery of the wound was sealed with an Eakin seal. Then, the entire area of the wound was covered with polyurethane film to ensure an enclosed environment.

Group 2

Two burn wounds were made on the back of each rat, equidistant from vertebral column. A 150‐g brass block measuring 15 × 15 mm was heated to 95°C and was placed on the back for 10 seconds to induce a third‐degree burn. Bacterial suspension (0·5 ml colony count: 1·0 × 107 CFU/wound) containing dextran beads was injected subcutaneously into the centre of each wound. No dressing was applied. Rats were injected intraperitoneally with 1·5 ml of physiological saline for fluid resuscitation.

Group 3

Two skin‐folds on the back of each rat were lifted and clamped with surgical mosquito forceps for 1 minute to induce ischaemia (dermal crush wound group). Bacterial suspension (0·5 ml colony count: 1·0 × 107 CFU/wound) containing dextran beads was injected subcutaneously into the centre of each wound. No dressing was applied.

In the second, main experiment, experimentally infected wounds in 40 rats were assigned to be inoculated with P. aeruginosa or S. aureus. Two 15 × 15 mm full‐thickness wounds penetrating the dartos fascia were prepared on the back of each rat, equidistant from vertebral column. A 15 × 15 mm piece of gauze (7·4 mg) was placed on the base of each wound, and 0·03 ml of a bacterial suspension was soaked into the gauze at a concentration of 1·5 × 106 CFU/wound. The periphery of each wound was sealed with an Eakin seal, after which the entire area was covered with polyurethane film to ensure an enclosed environment. The wound surface was wiped daily with sterile cotton and then covered with a new film. Wound exudate was transferred to a sterile stomacher bag containing 100 ml of physiological saline with Tween 80 and was homogenised for 2 minutes. A 1 ml sample of this solution was then diluted according to the 10‐fold dilution assay protocol. Two TSA plates were inoculated with 0·1 ml of the diluted homogenate and incubated for 18 hours at 35°C, after which total viable counts were taken. Two animals from each group were euthanised daily from the day following surgery until the ninth postoperative day. Animals were anaesthetised as described earlier and then euthanised by intracardiac injection of a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (150 mg/kg). The gauze was detached from the wound, and the tissue at the base of the wound was removed and weighed using aseptic techniques. The tissue was placed into a stomacher bag containing 100 ml of physiological saline with 0·1% Tween 80, washed for 2 minutes to sluice the surface bacteria and homogenised for 15 seconds in a Polytron homogeniser. The tissue was then homogenised for 1 minute in a glass homogeniser, after which it was placed in a stomacher bag containing 100 ml of physiological saline with 0·1% Tween 80 and homogenised for a further 2 minutes. A 1 ml sample of this homogenate was then diluted according to the 10‐fold dilution assay protocol.

The protocol for animal experimentation described here was approved by the Animal Research Committee of Teikyo University School of Medicine.

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviations were calculated after logarithmic transformation of the CFU values. Correlation coefficients were calculated using the Pearson method. A P‐value of less than 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Development of wound infections

In group 1 (full‐thickness wound group), full‐thickness wounds without gauze produced serous exudate for 3 days after inoculation with bacteria. After day 3, wounds were clear of pyogenic masses and granulation was observed. The presence of dextran beads in the bacterial suspension had no effect on the nature of the wounds. In full‐thickness wounds covered with gauze and inoculated with bacteria, wound contraction was not observed (1, 2). Furthermore, purulent discharge was obtained from these wounds for 7 days. However, evidence of inflammation, such as redness or swelling around the lesions, was not observed. After day 7, the seals around these wounds were broken and they became desiccated.

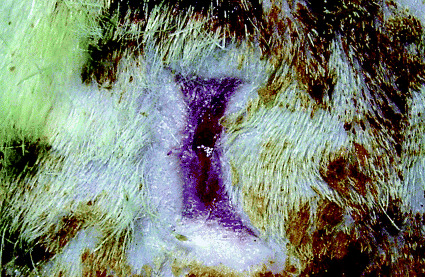

Figure 1.

Macroscopic appearances of the wound without gauze 7 days after inoculation with S. aureus. Marked wound contraction was observed with minimal exudate.

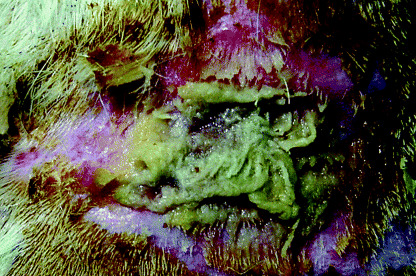

Figure 2.

Macroscopic appearances of the wound with gauze 7 days after inoculation with S. aureus. Purulent wound exudation was observed.

In group 2 (burn model), immediately after burning, the skin appeared erythematous and oedematous and remained so until day 3. Superficial eschar formation was observed in ten wounds on day 4, but purulent discharge was not obtained thereafter. On day 10, the burn site was excised and subcutaneous nodules were observed in three wounds. These nodules yielded purulent material, which was shown to contain neutrophils and numerous cocci by Gram staining (data not shown).

In group 3 (dermal crush wound group), epidermal necrosis with periwound oedema developed in all wounds immediately after trauma. In five of 20 wounds, subcutaneous nodules were observed at day 10. No drainage of wound fluid was observed up to day 10. These nodules were believed to be abscesses as they exhibited the same histological findings observed in the burn wounds (data not shown).

Bacterial counts

Tissue bacterial counts

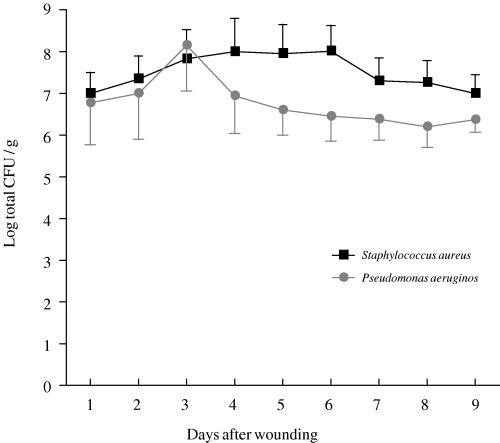

The number of viable bacteria present in all biopsy specimens is shown in Figure 3. For the established P. aeruginosa cell line, colony counts decreased slightly after peaking on day 4. In contrast, colony counts of the S. aureus clinical isolate decreased after peaking between days 3 and 6, and overall counts for S. aureus were greater than those for P. aeruginosa. There was no significant difference between the two bacterial challenges.

Figure 3.

Bacterial counts in tissue biopsies from infected wounds inoculated with S. aureus (–▪–) or P. aeruginosa (–•–). The points represent mean values for four wounds, and vertical bar represents the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Wound fluid

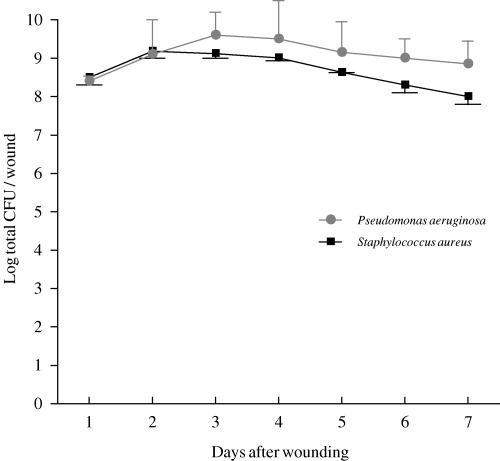

The number of viable bacteria present in all wound fluid (CFU/wound) is shown in Figure 4. Markedly higher bacterial counts (by approximately 2 log) were obtained from the exudate cultures than from the corresponding tissue biopsies. There were no significant statistical correlations between bacterial counts in wound fluid and numbers of bacteria observed in tissue biopsies.

Figure 4.

Bacterial counts in wound exudates from infected wounds inoculated with S. aureus (–▪–) or P. aeruginosa (–•–). The points represent mean values for four wounds, and vertical bar represents the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Discussion

Interactions between a pathogen and host depend on the local wound environment, as well as on host humoral and cellular responses to injury and infection, combined with pathogen virulence (4). In rodents, bacterial proliferation is reduced by phagocytosis and other immune responses (19). A model in which bacteria were inoculated under an autologous skin graft demonstrated evidence of wound healing from day 3 and on day 8 when a colony count of greater than 105 CFU/mg was observed in the tissue (19). In a guinea‐pig burn wound model, colonisation persisted 50 days after the burn was initiated, and evidence of gross infection characterised by purulent exudate was seen from day 10 through day 35 (20).

In the present study, skin ulceration and sustained purulent discharge was not achieved by burn injury or mechanical trauma. This finding is consistent with observations of previous experimental rodent models (5, 16). In the second part of this study, in which gauze was laid over a full‐thickness wound, over 106 CFU/mg of S. aureus or P. aeruginosa per mg of wound tissue was detected for 9 days, and the wound discharged exudate for 7 days. There were small differences in the counts obtained for S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, and this may have been due to the fact that the S. aureus strain was a clinical isolate. Differences in the virulence characteristics of microorganisms can affect results, as evidenced by the high mortality associated with experimental infection of burn wounds with human blood isolates (16). The model developed in this study mimics chronic wound infection, albeit for a relatively short time. The development of a more persistent model of wound infection will require experimentation in animals with impaired circulation, as occurs in diabetes.

In the present study, bacterial counts from samples of exudate were consistently 100 times greater than those obtained from tissue biopsies (CFU/wound). We noted no correlation between the bacterial counts of exudate cultures and tissue biopsies from each wound. The value of swabbing open wounds to determine bacterial load is a subject of continued debate (21, 22). A correlation between swab results and data from tissue sampling has been demonstrated. Levine et al. (23) support swab sampling as a reliable method for determining the number of viable bacteria colonising open wounds, keeping in mind that greater bacterial loads will be observed in exudate cultures than in the infected tissue. For example, swabs from patients with burn injuries revealed 106 viable bacteria/ml of wound fluid sampled, compared with 105 bacteria/g of tissue (21). However, Breuing et al. (20) have recently reported a poor correlation between bacterial counts obtained from surface culture and deep tissue biopsy in a pig model involving a liquid‐tight wound chamber. Therefore, further investigation is needed to clarify this issue.

Postoperative wound infections and non healing chronic skin ulcers have a significant impact on hospital costs, requiring increased durations of stay and additional treatment (1). Delayed healing may also lead to a loss of productivity. Nearly all chronic skin ulcers are colonised with potentially pathogenic bacteria which can delay or prevent wound healing (24). In immunocompromised patients or patients with devitalised tissue, it is more likely that colonisation will proceed to infection. There is continuous debate surrounding the treatment of chronic non healing wounds with topical antimicrobial agents and uncertainty with regard to which agents should be used (25, 26). The use of topical antiseptics is controversial (9, 25, 27, 28, 29). The results of some studies suggest that the cytotoxicity of these agents may exceed their bactericidal activity (1). Antiseptics can also be associated with side‐effects, such as contact dermatitis (30). More recent clinical trials have shown that cadexomer iodine has significant antimicrobial activity and that it stimulates the formation of granulation tissue and promotes wound healing in venous stasis ulcers (31).

Recently, a new approach to wound care has been developed involving topical administration of liposome‐entrapped antibiotics and the use of antimicrobial dressings (32). Recent experimental evidence has shown topical antibiotic therapy with controlled‐release poly(dl‐lactide‐coglycolide) cefazolin microspheres to be effective in the treatment of experimental methicillin‐resistant S. aureus surgical infections in rats (12). The possibility of achieving a high local concentration of antibiotic via controlled‐release delivery would be of particular benefit to patients in whom wounds are complicated by poor blood supply (33). This rat model of persistent wound infection may enable the effectiveness of topical antimicrobial agents and antimicrobial wound dressings to be investigated.

References

- 1. Schultz GS, Sibbald RG, Falanga V, Ayello EA, Dowsett C, Harding K, Romanelli M, Stacey MC, Teot L, Vanscheidt W. Wound bed preparation: a systematic approach to wound management. Wound Repair Regen 2003;11 Suppl: S1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bowler PG, Duerden BI, Armstrong DG. Wound microbiology and associated approaches to wound management. Clin Microbiol Rev 2001;14: 244–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bowler PG. Wound pathophysiology, infection and therapeutic options. Ann Med 2002;34: 419–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Robson MC. Wound infection. A failure of wound healing caused by an imbalance of bacteria. Surg Clin North Am 1997;77: 637–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bunce C, Wheeler L, Reed G, Musser J, Barg N. Murine model of cutaneous infection with gram‐positive cocci. Infect Immun 1992;60: 2636–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ogaard AR, Lausund P, Berdal BP. Observations on Pseudomonas aeruginosa proteolytic and toxic activity in experimentally infected rats. NIPH Ann 1992;15: 99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Felts AG, Giridhar G, Grainger DW, Slunt JB. Efficacy of locally delivered polyclonal immunoglobulin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a murine burn wound model. Burns 1999;25: 415–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Korpan NN, Resch KL, Kokoschinegg P. Continuous microwave enhances the healing process of septic and aseptic wounds in rabbits. J Surg Res 1994;57: 667–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lammers R, Henry C, Howell J. Bacterial counts in experimental, contaminated crush wounds irrigated with various concentrations of cefazolin and penicillin. Am J Emerg Med 2001;19: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaar E, Naziri W, Cheadle WG, Pietsch JD, Johnson M, Polk HC Jr. Improved survival in simulated surgical infection with combined cytokine, antibiotic and immunostimulant therapy. Br J Surg 1994;81: 1309–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boon RJ, Beale AS. Response of Streptococcus pyogenes to therapy with amoxicillin or amoxicillin‐clavulanic acid in a mouse model of mixed infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes . Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1987;31: 1204–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fallon MT, Shafer W, Jacob E. Use of cefazolin microspheres to treat localized methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in rats. J Surg Res 1999;86: 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kernodle DS, Kaiser AB. Comparative prophylactic efficacy of cefazolin and vancomycin in a guinea pig model of Staphylococcus aureus wound infection. J Infect Dis 1993;168: 152–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barg N. Comparison of four antibiotics in a murine model of necrotizing cutaneous infections caused by toxigenic Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus . J Antimicrob Chemother 1998;42: 257–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Warren MD, Kernodle DS, Kaiser AB. Correlation of in‐vitro parameters of antimicrobial activity with prophylactic efficacy in an intradermal model of Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 1991;28: 731–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bjornson AB, Bjornson HS, Lincoln NA, Altemeier WA. Relative roles of burn injury, wound colonization, and wound infection in induction of alterations of complement function in a guinea pig model of burn injury. J Trauma 1984;24: 106–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stevens EJ, Ryan CM, Friedberg JS, Barnhill RL, Yarmush ML, Tompkins RG. A quantitative model of invasive Pseudomonas infection in burn injury. J Burn Care Rehabil 1994;15: 232–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vaudaux P, Grau GE, Huggler E, Schumacher‐Perdreau F, Fiedler F, Waldvogel FA, Lew DP. Contribution of tumor necrosis factor to host defense against staphylococci in a guinea pig model of foreign body infections. J Infect Dis 1992;166: 58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stepinska M, Grzybowski J, Struzyna J, Olszowska M, Jablonska H, Chomicka M, Chomiczewski K. Mouse model of infected wound. Acta Microbiol Pol 1995;44: 39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Breuing K, Kaplan S, Liu P, Onderdonk AB, Eriksson E. Wound fluid bacterial levels exceed tissue bacterial counts in controlled porcine partial‐thickness burn infections. Plast Reconstr Surg 2003;111: 781–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bornside GH, Bornside BB. Comparison between moist swab and tissue biopsy methods for quantitation of bacteria in experimental incisional wounds. J Trauma 1979;19: 103–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saymen DG, Nathan P, Holder IA, Hill EO, Macmillan BG. Infected surface wound: an experimental model and a method for the quantitation of bacteria in infected tissues. Appl Microbiol 1972;23: 509–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levine NS, Lindberg RB, Mason AD Jr, Pruitt BA Jr. The quantitative swab culture and smear: a quick, simple method for determining the number of viable aerobic bacteria on open wounds. J Trauma 1976;16: 89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schneider M, Vildozola CW, Brooks S. Quantitative assessment of bacterial invasion of chronic ulcers. Statistical analysis. Am J Surg 1983;145: 260–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kramer SA. Effect of povidone‐iodine on wound healing: a review. J Vasc Nurs 1999;17: 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boyce ST, Holder IA. Selection of topical antimicrobial agents for cultured skin for burns by combined assessment of cellular cytotoxicity and antimicrobial activity. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993;92: 493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Howell JM, Dhindsa HS, Stair TO, Edwards BA. Effect of scrubbing and irrigation on staphylococcal and streptococcal counts in contaminated lacerations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1993;37: 2754–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakae H, Inaba H. Effectiveness of electrolyzed oxidized water irrigation in a burn‐wound infection model. J Trauma 2000;49: 511–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin SS, Ueng SW, Lee SS, Chan EC, Chen KT, Yang CY, Chen CY, Chan YS. In vitro elution of antibiotic from antibiotic‐impregnated biodegradable calcium alginate wound dressing. J Trauma 1999;47: 136–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burks RI. Povidone‐iodine solution in wound treatment. Phys Ther 1998;78: 212–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Holloway GA Jr, Johansen KH, Barnes RW, Pierce GE. Multicenter trial of cadexomer iodine to treat venous stasis ulcer. West J Med 1989;151: 35–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Trafny EA, Stepinska M, Antos M, Grzybowski J. Effects of free and liposome‐encapsulated antibiotics on adherence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to collagen type I. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1995;39: 2645–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mi FL, Wu YB, Shyu SS, Schoung JY, Huang YB, Tsai YH, Hao JY. Control of wound infections using a bilayer chitosan wound dressing with sustainable antibiotic delivery. J Biomed Mater Res 2002;59: 438–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]