Abstract

Background:

Integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)-based antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been associated with excess weight gain in some adults, which may be influenced by genetic factors. We assessed mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroups and weight gain following switch to INSTI-based ART.

Methods:

All AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5001 and A5322 participants with mtDNA genotyping who switched to INSTI were included. mtDNA haplogroups were derived from prior genotyping algorithms. Race/ethnicity-stratified piecewise linear mixed effects models assessed the relationship between mtDNA haplogroup and weight change slope differences before and after switch to INSTI.

Results:

291 adults switched to INSTI: 78% male, 50% non-Hispanic White, 28% non-Hispanic Black, and 22% Hispanic. The most common European haplogroups were H (n=66 [45%]) and UK (32 [22%]). Non-H European haplogroups had significant increase in weight slope after the switch. This difference was greatest among non-H clade UK on INSTI-based regimens that included tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) (3.67 [95% CI 1.12, 6.21] kg/year; p=0.005). Although small sample size limited analyses among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic persons, similarly significant weight gain was seen among the most common African haplogroup, L3 (n=29 [39%]; slope difference 4.93 [1.54, 8.32] kg/year, p=0.005), after switching to TAF-containing INSTI-based ART.

Conclusions:

Those in European mtDNA haplogroup clade UK and African haplogroup L3 had significantly greater weight gain after switching to INSTI-based ART, especially those receiving TAF. Additional studies in large and diverse populations are needed to clarify mechanisms and host risk factors for weight gain after switching to INSTI-based ART, with and without TAF.

Introduction

Integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI)-based antiretroviral therapy (ART) has been associated with excess weight gain in multiple clinical trials and observational cohort data from people with HIV (PWH), particularly when combined with tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) [1–4]. The greatest weight gain has been observed in persons of Black race, especially among Black women. While environmental and social factors likely play a role, these data also raise the possibility of a potential underlying genetic component. For example, preliminary evidence suggests an association between greater weight gain and slow metabolizer CYP2B6 genotype in patients switching to INSTI from efavirenz-based therapy [5].

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) define a mitochondrial haplogroup that can be linked to prehistoric migration patterns and genetic disease risk [6, 7]. Mitochondrial haplogroups have been associated with both obesity in the general population [8–10] and regional fat changes in PWH on older ART regimens [11]. Mitochondria are present in adipocytes and influence metabolic pathways, energy expenditure, and obesity [12]. HIV and ART also affect mitochondrial function, though limited data are available to suggest potential mechanistic effects of INSTI or TAF-based therapies on mitochondria [13, 14]. We hypothesized that mtDNA haplogroups would be associated with weight changes following switch to INSTI, and that inclusion of TAF in the new regimen would further influence these effects.

Methods

Study population

In 2000, the ACTG observational protocol A5001 [15] began enrolling participants previously randomized to ART regimens in ACTG parent trials, and followed them every 4 months through 2013. In 2013, A5001 follow-up ended and A5001 participants originally from ART-naïve parent trials who were ≥40 years of age were offered enrollment into ACTG observational protocol A5322, which follows participants every 6 months. Standardized weight was captured at every 4-month visits on A5001 and yearly in A5322. The present analyses included INSTI-naïve A5001 and A5322 participants who switched to INSTI-based ART (with or without concomitant switch to TAF) by the end of May 2019, were non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, or Hispanic, and had mtDNA genotyping available. The analysis was restricted to the two years prior to and two years following switch. All switchers had at least one weight assessment: 275 had at least one weight assessment prior to and one following switch; 209 had at least two weight measurements prior to and two following switch. All participants provided written informed consent for the parent protocols that were approved by the local institutional review board at each site.

Mitochondrial Haplogroup

Protocol A5128 is a platform protocol to collect specimens for future genetic research from consenting participants enrolled in ACTG studies. Samples from A5128 were used to generate genome-wide genotype data by the following for each ACTG parent study which fed into A5001 and A5322: Illumina HumanHap 650Y array for ACTG study A5095, Illumina 1M duo array for ACTG384, A5142 and A5202 [16] and Illumina HumanCore Exome Chip for A5257 [17]. Annotation of the SNP positions on the mtDNA chromosome were corrected to the standard rCRS reference sequence by comparison to a previous population level study [18]. HaploGrep 2 was then used to assign mitochondrial haplogroup based on the genotyped mtDNA SNPs [19]. The resulting haplogroup assignments were then collapsed to the major groups within each continental ancestry (H, UK, J, T, and other in non-Hispanic White participants; L0L1, L2, L3, and other in non-Hispanic Black participants; and A, B, C, and other in Hispanic participants).

Statistical approach

Basic summary statistics for demographics and other covariates at INSTI switch were calculated by race/ethnicity and then by mtDNA haplogroup for each race/ethnicity. We first visually examined the overall pattern of change in weight by mtDNA haplogroups during the 2 years pre- and post-switch using LOESS plots by haplogroups for each race/ethnicity group, and also stratifying by sex assigned at birth. We then calculated the annualized slope of weight change before and after switch for each participant who had weight measured at multiple (≥2) time points both before switch and after switch, then summarized the number and proportion of participants who had a greater after-INSTI slope compared with their before-INSTI slope. Piecewise linear mixed effects models were used to assess the relationship between weight before and after first switch to INSTI and mtDNA haplogroup in all available participants, allowing participants to serve as their own controls for estimation of weight changes. We fit linear spline models with a single knot at the time of the switch. All models were stratified by race/ethnicity, and additionally by sex assigned at birth (within each race/ethnicity group). Because of the small sample size, we did not adjust for other covariates. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted, limited to persons with suppressed HIV-1 RNA at time of INSTI switch.

Results

Among 1083 participants who switched to an INSTI-containing regimen, 291 white, black, or Hispanic persons had mtDNA data available. Of the 291 participants, 239 (82%) were enrolled in both A5001 and continued onto A5322; the median pre-switch observation period was 1.8 years and post-switch 1.5 years. The majority (78%) of participants were male, 50% non-Hispanic White, 28% non-Hispanic Black and 22% Hispanic (Table). Median age at switch was 50 years, CD4+ T cell count was 612 cells/μL and BMI was 27.0 kg/m2; 89% had HIV-1 RNA <200 copies/mL at or before switch to INSTI. ART was changed from protease inhibitor (PI)-based regimens in 72% of participants and from non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) in 27%. Seventy-three (25%) participants switched to raltegravir, 106 (36%) to elvitegravir/cobicistat, 102 (35%) to dolutegravir and 10 (3%) to bictegravir. INSTI-regimens were paired with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF, 47%), TAF (26%), or abacavir (20%). Nine (3%) were on TAF prior to switch, and 6 of 9 (67%) continued TAF with INSTI switch. The most common European haplogroup was H (n=66 [45%]) followed by UK (32 [22%]); the most common African haplogroups were L3 (32 [39%]) and L2 (25 [30%]); and the most common Hispanic haplogroup was A (19 [30%]), consistent with population frequencies. The mean weight and BMI and the categories of body weight pre-switch and following switch are shown by haplogroup in the Supplemental Tables.

Table.

Demographics at time of INSTI switch

| Total N=291 | White n=146 | Black n=82 | Hispanic n=63 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50 (45, 57) | 50 (46, 58) | 51 (45, 57) | 48 (41, 55) |

| Female | 63 (22%) | 14 (10%) | 29 (35%) | 20 (32%) |

| Pre-switch regimen | ||||

| PI regimen | 209 (72%) | 101 (69%) | 65 (79%) | 43 (68%) |

| NNRTI regimen | 80 (27%) | 43 (29%) | 17 (21%) | 20 (32%) |

| Switch regimen | ||||

| Elvitegravir/cobicistat | 106 (36%) | 60 (41%) | 25 (30%) | 21 (33%) |

| Raltegravir | 73 (25%) | 32 (22%) | 22 (27%) | 19 (30%) |

| Dolutegravir | 102 (35%) | 52 (36%) | 31 (38%) | 19 (30%) |

| Bictegravir | 10 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (5%) | 4 (6%) |

| CD4 T-cell count in cells/uL | 612 (454, 836) | 627 (461, 860) | 656 (470, 885) | 583 (349, 784) |

| HIV-1 RNA < 200 copies/mL | 258 (89%) | 138 (95%) | 70 (85%) | 50 (79%) |

| BMI in kg/m2 | 27.0 (23.5, 30.6) | 26.6 (23.3, 29.6) | 27.5 (23.6, 32.7) | 27.2 (24.2, 29.7) |

| Current or prior tobacco smoker | 176 (60%) | 88 (60%) | 49 (60%) | 39 (62%) |

| Current substance use | 34 (22%) | 16 (20%) | 14 (33%) | 4 (13%) |

| Physical activity <3 days/week of moderate or vigorous activities | 67 (44%) | 37 (46%) | 18 (42%) | 12 (41%) |

Values presented as median, IQR (interquartile range) or N (%)

PI, protease inhibitor; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; BMI, body mass index

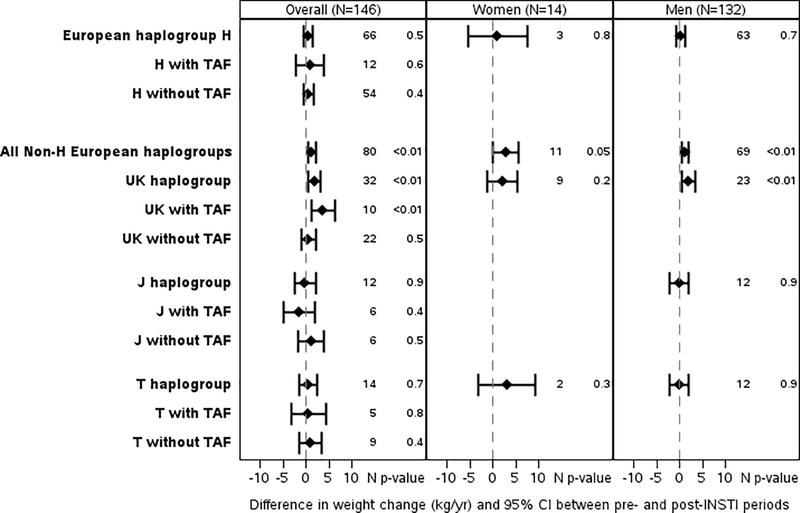

Among the European haplogroups, non-H haplogroups (n=80) had significantly greater slopes of weight increase after (1.79 [1.21, 2.37] kg/year) vs. before switch (0.55 [0.15, 0.94] kg/year; slope difference 1.25 [95% confidence interval 0.11, 2.08] kg/year; p=0.003). This difference was greatest among non-H clade UK on INSTI-based regimens including TAF (3.67 [1.12, 6.21] kg/year; p=0.005). Associations persisted when restricted to those with suppressed HIV-1 RNA at switch, (3.66 [0.73, 6.60] kg/year, p=0.01) and adjusted for PI or NNRTI prior to switch (3.81 [1.22, 6.39] kg/year, p=0.004). Differences by sex were limited by small sample size and therefore not separated by TAF or no-TAF, Figure 1A.

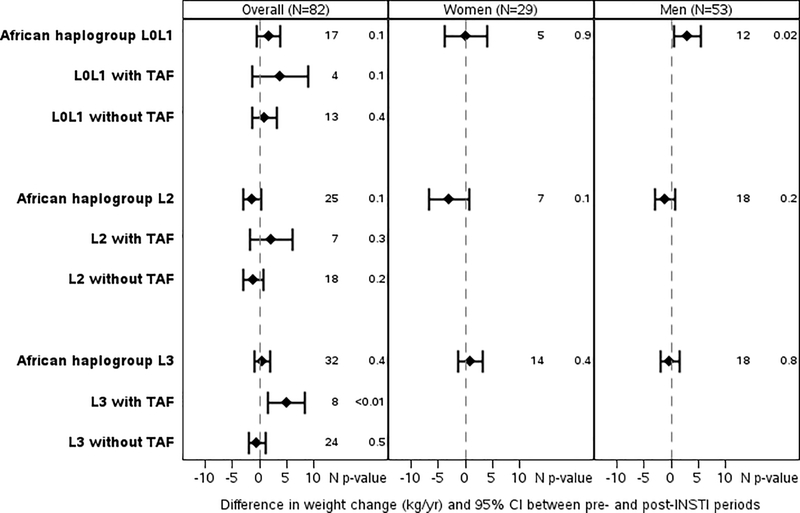

Figure 1.

Each plot shows the mean difference in weight change (kg/yr) indicated by the diamond and the 95% confidence interval (indicated with bars) pre- and post- switch to integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI). European haplogroups are shown in Figure 1A, African/Black haplogroups are shown in Figure 1B, and Hispanic haplogroups in Figure 1C. The changes are further broken down by whether the participant’s INSTI regimen was paired with tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) or by sex (TAF groups by sex are not shown as the numbers in these subgroups were often very limited).

Among non-Hispanic Black haplogroups, the L3 haplogroup was associated with significantly greater weight increase after (3.46 [1.10, 5.82] kg/year) vs before switch (−1.47 [−2.94, 0.76] kg/year) among persons receiving TAF (slope difference 4.93 [1.54, 8.32] kg/year, p=0.005) while no significant differences were seen with non-TAF containing regimens (−0.46 [−1.97, 1.05] kg/year, p=0.5). The L3 haplogroup effect persisted when restricted to those with suppressed HIV-1 RNA at switch (7.75 [3.70, 11.80] kg/year, p<0.001). Other haplogroup effects were not as apparent, clinically or statistically, Figure 1B.

Among Hispanics, B haplogroup with switch to INSTI + TAF was associated with significant decrease in weight after compared to before switch (slope difference −26.78 [−43.24, −10.32] kg/year, p=0.001) and C haplogroup individuals experienced weight loss after vs before switch to INSTI without TAF (slope difference −5.96 [−9.71, −2.21] kg/year, p=0.002). However, these data only included one individual from B haplogroup and five individuals from the C haplogroup, and should be interpreted with caution. No Hispanic haplogroups were associated with significant weight gain, Figure 1C.

Discussion

In a cohort of adults of diverse ancestry switching to INSTI-based therapy with or without a concomitant change to TAF, we found evidence that some mtDNA haplogroups may be associated with significantly greater weight gain following switch. Haplogroup clade UK among non-Hispanic White persons had significantly greater annualized weight gain after switching to INSTI-based ART; differences were accentuated in those also receiving TAF. Although our subgroup numbers were limited, a significant weight gain with the L3 haplogroup among African participants is of particular interest in the context of the ADVANCE trial, where marked weight gains were observed in the context of INSTI + TAF among African patients [4]. In contrast, Hispanic haplogroups B and C had no evidence of weight gain following switch to INSTI.

While certain haplogroups have been linked to obesity in other cohorts without HIV, the mechanism underlying these changes are unknown, though may be related to mitochondrial regulation of mitochondrial rate [20] or the role of mitochondria in adipogenesis [21]. However, findings are limited to European or Asian haplogroups. The T haplogroup has been associated with obesity in an Austrian cohort [8] and in morbidly obese Italians [9], both inclusive of only European haplogroups. A cohort of >2000 persons in the US found higher risk of obesity with an IWX haplogroup but was restricted to White, non-Hispanic participants [10]. Arab individuals with the H haplogroup had lower prevalence of obesity [22]. In an Asian population, F4 was a risk factor for obesity [23], while women with N9A had a lower risk of metabolic syndrome [24]. Other mitochondrial genetic features such as lower mitochondrial DNA copy number have also been associated with weight gain over time [25, 26], and mitochondrial SNPs mt4823 and mt8873 with increased body fat mass in European haplogroups [27]. Little is known about the role of mitochondrial haplogroups in relation to medication-related weight gain. Among persons of European haplogroup experiencing antipsychotic related weight gain (n=168), nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes but not haplogroup were associated with weight gain [28].

Our study was limited by the number of persons with available mtDNA analyses, and small numbers in subgroups by sex and race/ethnicity, and small numbers on specific INSTI regimens, but provides preliminary evidence that mitochondrial haplogroup may help identify those at greatest risk for weight gain following ART switch to INSTI-based regimens. Additional studies in large and diverse populations are needed to clarify mechanisms and host risk factors for weight gain after switching to INSTI-based ART, with or without a synergistic effect of TAF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding. This study was supported in part through funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (R01 AG054366 to KME); and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01 AI077505, UM1 AI069439, P30 AI110527, TR 002243 (DWH); K24 AI120834 (TTB); UM1AI068634).

Clinical research sites that participated in ACTG protocols A5001 and A5322, and collected DNA under protocol A5128 were supported by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH): A1069412, A1069423, A1069424, A1069503, AI025859, AI025868, AI027658, AI027661, AI027666, AI027675, AI032782, AI034853, AI038858, AI045008, AI046370, AI046376, AI050409, AI050410, AI050410, AI058740, AI060354, AI068636, AI069412, AI069415, AI069418, AI069419, AI069423, AI069424, AI069428, AI069432, AI069432, AI069434, AI069439, AI069447, AI069450, AI069452, AI069465, AI069467, AI069470, AI069471, AI069472, AI069474, AI069477, AI069481, AI069484, AI069494, AI069495, AI069496, AI069501, AI069501, AI069502, AI069503, AI069511, AI069513, AI069532, AI069534, AI069556, AI072626, AI073961, TR000004, TR000058, TR000124, TR000170.

Conflicts of Interest: KME has received payments for consultancy from Gilead and ViiV Pharmaceuticals and Gilead Sciences. TTB has received payments for consultancy from Gilead Sciences, Merck, Theratechnologies, and ViiV Healthcare. SHB has received grant funding to her institution from Gilead Sciences. JEL has received grants from and served as a consultant to Gilead Sciences. JRK has received grants from and/or served as a consultant to Gilead Sciences and Theratechnologies.

Footnotes

Data availability for GWAS: Access to deidentified clinical and genetic data from this study may be obtained by submitting a Data Request to the AIDS Clinical Trial Group, using the Proposal Submission System at https://submit.actgnetwork.org/.

References

- 1.Sax PE, Erlandson KM, Lake JE, et al. Weight Gain Following Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy: Risk Factors in Randomized Comparative Clinical Trials. Clin Infect Dis 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bourgi K, Jenkins CA, Rebeiro PF, et al. Weight gain among treatment-naive persons with HIV starting integrase inhibitors compared to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors or protease inhibitors in a large observational cohort in the United States and Canada. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2020; 23(4): e25484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lake JE, Wu K, Bares SH, et al. Risk Factors for Weight Gain Following Switch to Integrase Inhibitor-Based Antiretroviral Therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venter WDF, Moorhouse M, Sokhela S, et al. Dolutegravir plus Two Different Prodrugs of Tenofovir to Treat HIV. N Engl J Med 2019; 381(9): 803–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griesel R, Maartens G, Sokhela S, et al. CYP2B6 Genotype and weight-gain differences between dolutegravir and efavirenz, Presented at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (virtual), 3/10/2020. Abstract 82. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hart AB, Samuels DC, Hulgan T. The other genome: a systematic review of studies of mitochondrial DNA haplogroups and outcomes of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy. AIDS reviews 2013; 15(4): 213–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial genetic medicine. Nature genetics 2018; 50(12): 1642–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebner S, Mangge H, Langhof H, et al. Mitochondrial Haplogroup T Is Associated with Obesity in Austrian Juveniles and Adults. PLoS One 2015; 10(8): e0135622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nardelli C, Labruna G, Liguori R, et al. Haplogroup T is an obesity risk factor: mitochondrial DNA haplotyping in a morbid obese population from southern Italy. Biomed Res Int 2013; 2013: 631082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veronese N, Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, et al. Mitochondrial genetic haplogroups and incident obesity: a longitudinal cohort study. European journal of clinical nutrition 2018; 72(4): 587–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hulgan T, Haubrich R, Riddler SA, et al. European mitochondrial DNA haplogroups and metabolic changes during antiretroviral therapy in AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5142. Aids 2011; 25(1): 37–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Mello AH, Costa AB, Engel JDG, Rezin GT. Mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity. Life Sci 2018; 192: 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blas-Garcia A, Polo M, Alegre F, et al. Lack of mitochondrial toxicity of darunavir, raltegravir and rilpivirine in neurons and hepatocytes: a comparison with efavirenz. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69(11): 2995–3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moure R, Domingo P, Gallego-Escuredo JM, et al. Impact of elvitegravir on human adipocytes: Alterations in differentiation, gene expression and release of adipokines and cytokines. Antiviral Res 2016; 132: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smurzynski M, Collier AC, Koletar SL, et al. AIDS clinical trials group longitudinal linked randomized trials (ALLRT): rationale, design, and baseline characteristics. HIV clinical trials 2008; 9(4): 269–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International HIVCS, Pereyra F, Jia X, et al. The major genetic determinants of HIV-1 control affect HLA class I peptide presentation. Science 2010; 330(6010): 1551–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson DH, Venuto C, Ritchie MD, et al. Genomewide association study of atazanavir pharmacokinetics and hyperbilirubinemia in AIDS Clinical Trials Group protocol A5202. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2014; 24(4): 195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pereira L, Freitas F, Fernandes V, et al. The diversity present in 5140 human mitochondrial genomes. Am J Hum Genet 2009; 84(5): 628–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weissensteiner H, Pacher D, Kloss-Brandstatter A, et al. HaploGrep 2: mitochondrial haplogroup classification in the era of high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res 2016; 44(W1): W58–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Natarajan V, Chawla R, Mah T, et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Age-Related Metabolic Disorders. Proteomics 2020; 20(5–6): e1800404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bournat JC, Brown CW. Mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2010; 17(5): 446–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eaaswarkhanth M, Melhem M, Sharma P, et al. Mitochondrial DNA D-loop sequencing reveals obesity variants in an Arab population. Appl Clin Genet 2019; 12: 63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chalkia D, Chang YC, Derbeneva O, et al. Mitochondrial DNA associations with East Asian metabolic syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg 2018; 1859(9): 878–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka M, Fuku N, Nishigaki Y, et al. Women with mitochondrial haplogroup N9a are protected against metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 2007; 56(2): 518–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meng S, Wu S, Liang L, et al. Leukocyte mitochondrial DNA copy number, anthropometric indices, and weight change in US women. Oncotarget 2016; 7(37): 60676–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hang D, Nan H, Kværner AS, et al. Longitudinal associations of lifetime adiposity with leukocyte telomere length and mitochondrial DNA copy number. Eur J Epidemiol 2018; 33(5): 485–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang TL, Guo Y, Shen H, et al. Genetic association study of common mitochondrial variants on body fat mass. PLoS One 2011; 6(6): e21595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mittal K, Gonçalves VF, Harripaul R, et al. A comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial genes variants and their association with antipsychotic-induced weight gain. Schizophrenia research 2017; 187: 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.