Abstract

Medicare Advantage (MA) plans have increasing flexibility to provide nonmedical services to support older adults aging in place in the community. However, prior research has suggested that enrollees with functional disability (hereafter, “disability”) were more likely than those without disability to leave MA plans. This indicates that MA plans might not meet the needs of older adults with disability. We used data for 2011–16 from the National Health and Aging Trends Study linked to Medicare claims to measure and characterize switches in either direction between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in the twelve months before and after onset of disability. While the rate of switches from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare increased slightly after disability onset, people with greater levels of disability were more likely to switch to traditional Medicare, compared to those with lower levels: 36 percent of those who switched from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare needed help with two or more activities of daily living, compared to 14.3 percent of those who switched from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage. This indicates the potential benefit of including functional measures in MA plan risk adjustment and quality measures. Furthermore, the highest-need older adults with disability may experience lower-quality care in Medicare Advantage and thus leave before accessing the program’s expanded benefits.

Since its inception in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Medicare Advantage (MA) has expanded to insure 34 percent of Medicare beneficiaries in 2018, and it is predicted to continue to grow in this decade.1 However, evidence that older adults leave the program when they become seriously ill suggests that Medicare Advantage might not be adequately meeting the needs of all Medicare beneficiaries. Older adults newly on dialysis, using high-cost medical services, or with multimorbidity disenroll from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare at higher rates than their counterparts do.2–4

Similarly, older adults with disability (that is, those who need assistance to meet their daily care needs) may leave MA plans at higher rates than those without disability. Existing data on the characteristics of people switching from Medicare Advantage are based on claims data, which do not contain measures of function. This makes it difficult to characterize the relationship between the onset and degree of functional disability (hereafter, “disability”) and disenrollment from Medicare Advantage. However, older adults who rely on services fundamental to coping with disability, such as home health and nursing home care, are more likely to switch from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare.3,4

While MA plans are required to cover all services covered by traditional Medicare (with the exception of hospice, which is carved out of MA plans),5 there are several reasons why older adults may be more likely to switch from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare after becoming disabled. To control costs for postacute care often needed by older adults with disability, MA plans may limit networks of skilled nursing facilities, pressure the facilities to shorten beneficiary lengths-of-stay, and employ burdensome prior authorization procedures.6 Limited provider networks may affect the quality of care and satisfaction of MA beneficiaries, as older adults in Medicare Advantage are more likely than those in traditional Medicare to be served by skilled nursing facilities and home health agencies with lower quality ratings.7,8 Limited networks and less flexible options may especially challenge people with disability, who often rely on caregivers. The additional coordination needed to find in-network, accessible providers in MA plans may be a barrier.9 This raises the concern that participation in Medicare Advantage poses unique barriers to care for older adults with disability. This is especially worrisome given that this population is highly vulnerable, with high levels of health needs and risk of significant morbidity and mortality—especially if their needs are not met.10–15

Assessing the impact of disability on switching between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare is also critical to ensuring the adequacy of current risk-adjustment approaches to determine MA payment. Disability is a stronger predictor of total expenditures, expenditures at the end of life, and readmissions than medical conditions alone are.16–20 While current risk-adjustment approaches that consider specific medical conditions have reduced some adverse selection of healthier and low-cost patients into Medicare Advantage, the growth in Medicare Advantage increases the stakes for overpayment to MA plans.

Despite concerns about the experience of older adults with disability in Medicare Advantage, changes in the program might better position MA plans in the future to support older adults with disability. The Creating High-Quality Results and Outcomes Necessary to Improve Chronic (CHRONIC) Care Act of 2017 expands the ability of MA plans to offer nonmedical services focused on caregiving and home supports, such as home repairs, telehealth supports, and home health aide hours.21 Proposals to “carve in” hospice care to MA plans may allow even further flexibility for plans to offer enriched services to people with disability.5

However, even with benefit expansion under the CHRONIC Care Act, if older adults with disability—especially those from more vulnerable sociodemographic populations or with greater care needs—leave MA plans after they become disabled, they will not have access to the expanded benefits of the CHRONIC Care Act. Moreover, high rates of disenrollment from MA plans among older adults with disability would indicate that the structure of the current MA program is not meeting the needs of this high-need population. Given prior evidence that nonwhite beneficiaries disenroll from MA plans at higher rates than white beneficiaries do,22 it is important to understand the rates of switching from Medicare Advantage for beneficiaries who are nonwhite, from vulnerable sociodemographic groups, or both in the context of disability.

We used information from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) to assess switching between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare twelve months before and after new-onset disability. The study is a longitudinal, nationally representative survey of aging that contains rich data on function, household context, and sociodemographics that we linked to Medicare claims data. Because it asks respondents to report the specific month when they began to need help with activities of daily living, we were able to examine the interplay between clinical and sociodemographic characteristics and the onset of disability in influencing switches between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. We hypothesized that switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare would be more frequent after disability than before, while switching from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage after disability would not increase; and that older adults with disability who switched from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare would be more likely to be from lower socioeconomic groups and have higher levels of disability.

Study Data And Methods

SAMPLE

Data from 2011–16 were drawn from NHATS, a population-based survey of aging that follows a sample of adults ages sixty-five and older.23 With respondents’ consent, the survey data were linked to the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File and Hospice file. We defined the onset of disability as the respondent-reported month of first needing help with either any self-care activity (eating, getting cleaned up, using the toilet, or getting dressed) or mobility (getting out of bed, getting around home, or leaving the building). Given that hospice is not included as a benefit in the MA program, older adults who were enrolled in hospice prior to the study start (twelve months prior to the onset of disability) were excluded.5

MEASURES

Using the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File, we assessed monthly enrollment status in either Medicare Advantage or traditional Medicare in the twelve months before and after disability onset to identify switches between the programs. If a survey respondent switched more than once, only the first switch was counted. Switches that occurred within fourteen days of admission to hospice were not classified as switches, given that they could reflect enrollment in hospice. The incidence of switches (that is, the number of switches per person-months of observation) was calculated to allow for the variable amounts of time in which respondents were observed. Starting twelve months before disability onset, individuals were observed until whichever event occurred first: switching in either direction between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, enrolling in hospice, or becoming disabled. This resulted in an individual’s contributing data on a maximum of twelve months, or twelve person-months, before disability onset. After disability onset, older adults were observed either for another twelve months or until the first of the following events: switching in either direction between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, hospice enrollment, death, or truncated follow-up due to the availability of data from NHATS. Therefore, an individual could contribute a maximum of twelve person-months following disability onset.

Respondents’ demographic and household characteristics measured via the NHATS survey before and after the onset of disability included sex, age, race, region, whether respondents lived alone, and whether respondents were married or partnered. Socioeconomic status variables included education, income, and Medicaid enrollment. Clinical and health characteristics included the number of activities of daily living that the respondent reported receiving help with after the onset of disability (a range of one to twelve months after disability); if disabled, whether the respondent reported having help from unpaid friends or family members; probable or possible dementia, as determined by the survey protocol;24 residing in a nursing home; homebound, as measured by the frequency of and difficulty with leaving home;25 depression, as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire–2 scale; anxiety, as measured by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder–2 scale; self-reported health; and whether the respondent died within twelve months of disability onset, as determined by NHATS surveyors and claims files. Time-varying characteristics (income, Medicaid enrollment, anxiety, depression, and so on) were derived from the survey wave before disability onset.

We also assessed to what extent switches were due to open enrollment versus other circumstances. Switches that occurred on January 1 of any calendar year were considered to have occurred during the open enrollment period, when people can freely switch between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. These switches automatically go into effect on January 1. In addition, we used the Minimum Data Set linked to information from NHATS to identify whether people were residing in a skilled nursing facility or nursing home, and we used the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File to identify Medicaid enrollment at the time of the switch—circumstances that allow beneficiaries to switch plans.26 These categories of switches (during open enrollment, if a person was residing in a skilled nursing facility or nursing home, and if a person was enrolled in Medicaid) were not mutually exclusive.

ANALYSIS

We first compared the characteristics of respondents twelve months before disability onset by whether they were enrolled in Medicare Advantage or traditional Medicare. We then assessed the incidence rate per 1,000 person-years for switches from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare and vice versa over the twelve months before and after disability onset. As described above, this allowed us to observe respondents for variable amounts of time. We calculated 95% confidence intervals for switch rates for those initially enrolled in Medicare Advantage and those initially enrolled in traditional Medicare.

We then assessed the characteristics of those who did not switch, compared to those who did, stratifying by which program they were enrolled in before disability onset. This allowed us to discern whether characteristics were associated with the “base” rate of switching as opposed to excess switching that favored either Medicare Advantage or traditional Medicare. We then assessed the incidence rates of switching before and after disability for white versus nonwhite respondents, again differentiated by which program they were enrolled in before disability. As a sensitivity test, we repeated all analyses, excluding people newly enrolled in Medicare (those younger than age sixty-seven)—who might be less affected by Medigap policies.27 Survey weights were used for all analyses to account for the complex survey design of NHATS.

LIMITATIONS

While our study is unique in that it is nationally representative and contains nuanced insurance, household, and disability data, it had several limitations. First, our sample size did not allow us to build complex multivariable regression models to assess factors that were independently associated with switching.

Second, because of sample size and data reporting restrictions, we could not use more granular measures of race/ethnicity to examine switching patterns. While we had the advantage of identifying the month when disability was first experienced, disability can be a fluctuating condition, and in this analysis we did not differentiate between different trajectories of disability. However, our previous work has demonstrated that even people who recover have a high likelihood of repeated disability in time.10

Third, we did not have survey information on the drivers of switches, including patients’ perceptions of and satisfaction with their plans.

Fourth, with the data available, we were unable to examine the plan characteristics associated with switches, such as designated Special Needs Plans. We could not determine whether a person was automatically switched from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage as someone dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid who resided in a state testing a Medicare-Medicaid program,28 although we could examine the proportion of people switching who were enrolled in Medicaid.

Fifth, we were unable to assess the variety of factors that could lead to a switch, such as the development of a new chronic condition, switching to an out-of-network physician, or a change in a plan contract. However, information derived from NHATS and Medicare claims allowed us to describe the context of a switch, such as whether it was during open enrollment, Medicaid enrollment, or residence in a nursing home or skilled nursing facility.

Study Results

We assessed the switching patterns of 3,592 Medicare beneficiaries with a new disability, 30.7 percent of whom were enrolled in Medicare Advantage twelve months before disability. The sociodemographic characteristics of those who started in Medicare Advantage twelve months prior to disability were substantially different from the characteristics of those who started in traditional Medicare. Compared to those in traditional Medicare, those in Medicare Advantage were more likely to describe their race as nonwhite, less likely to live in the South and more likely to live in the West, and more likely to have not completed high school or to have an annual income of less than $15,000 (exhibit 1). They also had lower anxiety levels before disability. Given that this was a cohort of people who reported a new disability (measured in terms of new need for help for mobility or self-care), levels of other disability measures such as number of activities of daily living an individual received help with and homebound status were low and similar between those who started in Medicare Advantage and in traditional Medicare.

EXHIBIT 1.

Baseline characteristics of older adults in Medicare Advantage (MA) and traditional Medicare (TM) in the 12 months before the onset of functional disability

| Adults who started in: | ||

|---|---|---|

| MA (n = 1,186) | TM (n = 2,406) | |

| Adjusted proportion | 30.7% | 69.3% |

| Estimated population | 5,409,200 | 12,221,691 |

| demographic or household characteristics | ||

| Female | 60.9% | 60.2% |

| Mean age, years (SE)a | 78.1 (0.28) | 78.4 (0.21) |

| Nonwhite race | 24.4% | 15.4%*** |

| Lives alonea | 32.1 | 30.1 |

| Not married or partnereda | 46.2 | 45.2 |

| Region | ||

| South | 30.3 | 40.2** |

| Northeast | 17.5 | 16.8 |

| Midwest | 25.0 | 24.7 |

| West | 27.2 | 18.4** |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Did not complete high school | 27.6 | 20.7*** |

| Annual income less than $15,000a | 23.6 | 19.7** |

| Enrolled in Medicaida | 17.0 | 14.3 |

| clinical and health care characteristics | ||

| Impaired ADLs at survey following onset of disabilityb | ||

| 0 (recovered) | 87.4% | 90.2% |

| 1 | 11.9 | 9.0 |

| 2 or more | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| No unpaid helpers if receiving help for any ADLs | 11.2 | 13.2 |

| Nursing home resident | —c | —c |

| Homebound status | ||

| Independent, not homebound | 75.3 | 74.4 |

| Leaves home but needs assistance or has difficulty | 18.5 | 20.2 |

| Never or rarely leaves home | 6.2 | 5.4 |

| Probable or possible dementiaa | 25.0 | 23.0 |

| Depression per PHQ-2 scalea | 17.0 | 14.5 |

| Anxiety per GAD-2 scalea | 11.2 | 15.1** |

| Self-reported health fair or poora | 33.1 | 31.1 |

source Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) linked to Medicare claims for 2011–16. notes All estimates are adjusted for survey weighting and design. Percentages might not sum to 100 because of rounding. SE is standard error. ADLs are the number of activities of daily living the individual received help with. PHQ is Patient Health Questionnaire. GAD is Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

Variable from the NHATS survey from the year before that in which a new disability was reported.

Variable from the NHATS survey from the year after that in which a new disability was reported.

Not reported because of the NHATS restrictions on data about samples smaller than 11.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

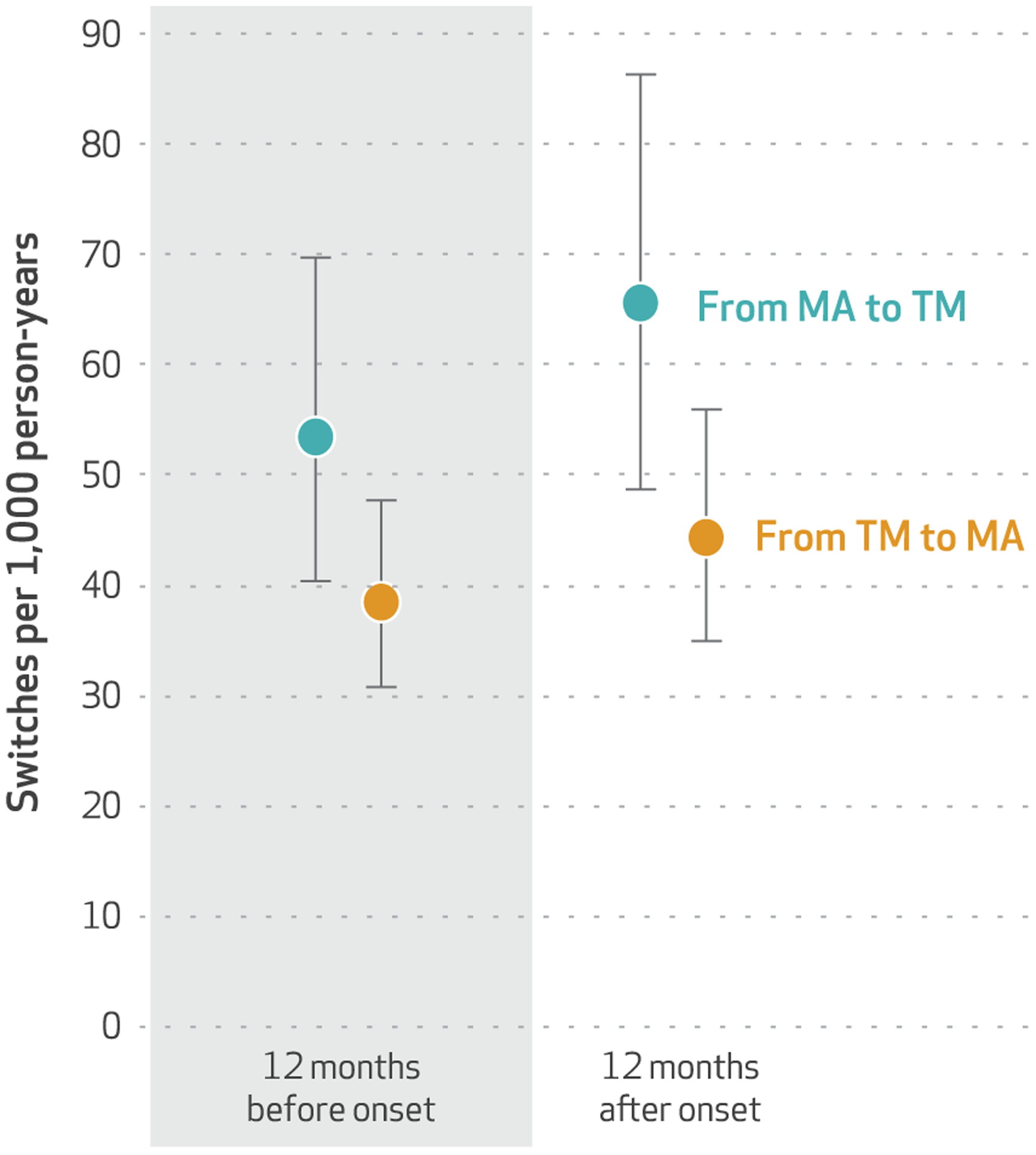

In total, 10.6 percent of those who were initially in Medicare Advantage switched to traditional Medicare, and 6.7 percent of those initially in traditional Medicare switched to Medicare Advantage (data not shown). Before disability, the incidence of switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare was 53.5 switches per 1,000 person-years, and the incidence of switching from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage was 38.6 switches per 1,000 person-years (exhibit 2). After disability, the incidence of switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare increased to 65.6 switches per 1,000 person-years, compared to 44.4 switches per 1,000 person-years for those who started in traditional Medicare.

EXHIBIT 2. Switches between Medicare Advantage (MA) and traditional Medicare (TM) per 1,000 person-years in the 12 months before and after the onset of functional disability.

source Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study linked to Medicare claims for 2011–16. note The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The characteristics of people who stayed in their program instead of switching differed by whether people started in Medicare Advantage or traditional Medicare. Respondents who reported nonwhite versus white race and annual income of less than $15,000 versus higher incomes were more likely to switch than stay, regardless of which plan they started in (exhibit 3). However, both having a higher level of disability (receiving help with two or more activities of daily living, compared to having recovered after the onset of disability) and being homebound were associated with an overall preference for traditional Medicare (remaining in or switching to it). Other characteristics were associated with distinct patterns for switching based on whether the respondent started in Medicare Advantage or traditional Medicare plans. Characteristics associated with switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare included having less education, residing in a facility (nursing home or skilled nursing facility), and having depression. Characteristics associated with switching from traditional Medicare to MA included being younger, not residing in the Northeast, and having lower one-year mortality after disability—a proxy for better health and slower disease progression.

EXHIBIT 3.

Characteristics of older adults who stayed in or switched from Medicare Advantage (MA) to traditional Medicare (TM), or vice versa, in the 12 months before or after the onset of functional disability

| Started in MA | Started in TM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stayed in MA (n = 1,060) | Switched to TM (n = 126) | Stayed in TM (n = 2,244) | Switched to MA (n = 162) | |

| demographic or household characteristics | ||||

| Female | 61.3% | 56.6% | 60.4% | 57.3% |

| Mean age, years | 78.1 | 77.7 | 78.6 | 75.1*** |

| Nonwhite race | 21.9% | 46.5%*** | 15.0% | 20.5%* |

| Live alone | 30.0 | 40.2 | 32.4 | 37.7 |

| Not married or partnered | 47.4 | 51.1 | 45.7 | 49.9 |

| Region | ||||

| South | 29.6 | 36.1 | 40.3 | 38.7 |

| Northeast | 18.1 | 12.8 | 17.4 | 9.6* |

| Midwest | 24.9 | 26.4 | 24.1 | 32.1 |

| West | 27.5 | 24.7 | 18.2 | 19.7 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Did not complete high school | 26.4 | 38.5* | 20.2 | 26.5 |

| Annual income less than $15,000 | 22.2 | 32.3* | 18.2 | 24.7* |

| Enrolled in Medicaid | 15.9 | 26.4** | 15.0 | 21.2 |

| clinical and health care characteristics | ||||

| Impaired ADLs at survey following onset of disabilitya | ||||

| 0 (recovered) | 45.7% | 32.5%* | 42.6% | 48.3% |

| 1 | 31.6 | 31.5 | 33.7 | 37.4 |

| 2 or more | 22.8 | 36.1** | 23.6 | 14.3** |

| No informal helpers if any impaired ADL | 15.5 | 19.7 | 16.1 | 11.7 |

| Probable or possible dementia | 27.8 | 45.1*** | 28.5 | 21.4 |

| Homebound status | ||||

| Independent, not homebound | 45.4 | 31.0** | 45.7 | 49.6 |

| Leaves home but needs assistance or has difficulty | 37.8 | 37.3 | 35.6 | 40.2 |

| Never or rarely leaves home | 16.8 | 31.7*** | 18.7 | 10.2** |

| Depression per PHQ-2 scale | 17.6 | 28.5* | 21.2 | 24.6 |

| Anxiety per GAD-2 scale | 16.1 | 21.3 | 17.1 | 14.9 |

| Self-reported health fair or poor | 38.7 | 43.6 | 37.3 | 47.0* |

| Died in the 12 months after onset of disability | 17.7 | 17.6 | 17.0 | 8.2*** |

| Switch occurred during: | ||||

| Open enrollment | —b | 56.8 | —b | 59.5 |

| Medicaid enrollment | —b | 34.2 | —b | 26.2 |

| Residence in a facilityc | —b | —d | —b | 17.6*** |

source Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) linked to Medicare claims for 2011–16. notes All proportions and statistical tests were adjusted using survey weights to account for survey design and sampling approach. Percentages might not sum to 100 because of rounding. ADLs are the number of activities of daily living the individual received help with. PHQ is Patient Health Questionnaire. GAD is Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

Variable from the NHATS from the year after that in which a new disability was reported.

Not applicable.

Skilled nursing facility or nursing home that provided long-term care.

Not reported because of the NHATS restrictions on data about samples smaller than 11.

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

We found few differences in the characteristics of switches from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare compared to those of switches in the other direction. Over half of the switches (56.8 percent of those from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare and 59.5 percent of those from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage) occurred during the end-of-year open enrollment and took effect on January 1, which means that the remainder were due to one of the many special circumstances in which Medicare allows plan switching.26 One of these circumstances is being enrolled in Medicaid, which we found to be the case among 34.2 percent of the people who switched from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare and 26.2 percent of those who switched from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage. Switching outside of open enrollment is also allowed for people residing in a skilled nursing facility or nursing home. While the rate of switches from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare among facility residents was too low to report (due to data restrictions), switches from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage were significantly higher: 17.6 percent of those who switched resided in a facility. While these circumstances describe the context of switches, they are not mutually exclusive.

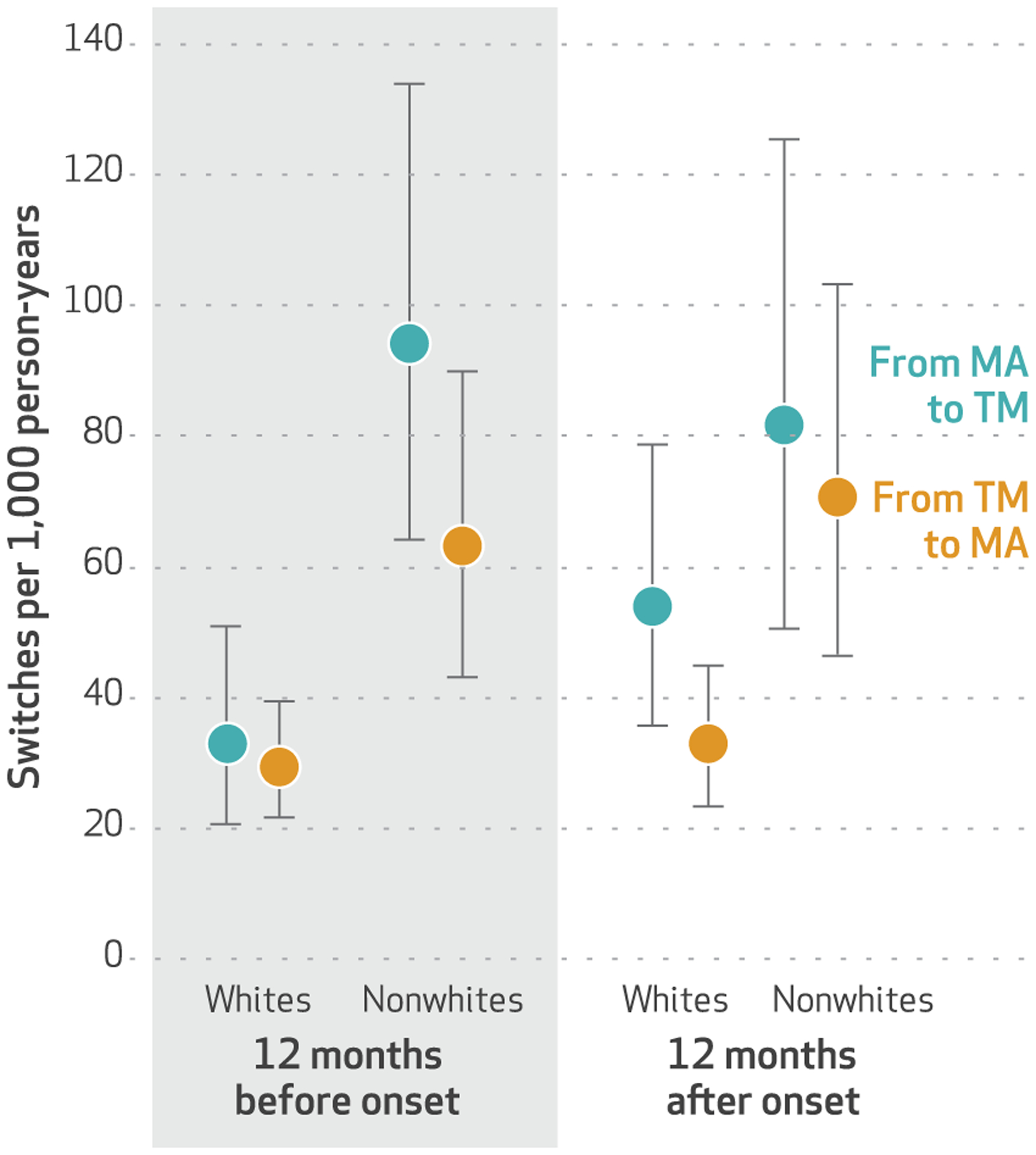

We separately calculated the incidence of switching by race before and after disability onset. For white respondents, the incidence of switching before disability was similar for those starting in Medicare Advantage and those in traditional Medicare (33.3 versus 29.7 switches per 1,000 person-years) (exhibit 4). After disability, the switch rate for white respondents starting in traditional Medicare remained almost the same (33.1 switches per 1,000 person-years), but the rate for those who started in Medicare Advantage increased (54.0 switches per 1,000 person-years). Nonwhite respondents had higher rates of switching both before and after disability, in particular those who started in MA plans: Before disability onset, those who started in MA plans had 94.3 versus 63.6 switches per 1,000 person-years for those in traditional Medicare. The rates after disability were 81.9 versus 71.0 switches per 1,000 person-years.

EXHIBIT 4. Switches between Medicare Advantage (MA) and traditional Medicare (TM) per 1,000 person-years in the 12 months before and after the onset of disability, by race.

source Authors’ analysis of data from the National Health and Aging Trends Study linked to Medicare claims for 2011–16. note The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

All analyses were repeated, excluding adults younger than age sixty-seven, as a sensitivity test. Only eleven people in the cohort were in that age group, and no results were substantially different from those in the primary analysis.

Discussion

This nationally representative study of adults ages sixty-five and older demonstrated that people are more likely to switch from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare following the onset of disability than from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage, and that the characteristics of people who switch from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare are different from those of people switching from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage. While other studies have demonstrated that high-need older adults are more likely to switch from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare than the reverse, this is the first study to show the temporal relationship between onset of disability and disenrollment from Medicare Advantage. Furthermore, older adults who are of nonwhite race or from high-risk socioeconomic groups are more likely to switch insurance coverage than are those of white race and with higher incomes and education levels, while those who are more severely disabled are more likely to prefer traditional Medicare. These findings have important implications for measuring quality, appropriately risk-adjusting payments, and reducing disparities within the MA program.

The higher rate of switching out of MA plans after disability onset raises concerns about the experience and quality of care of older adults in this program who become disabled. Given the active role that MA plans play in influencing postacute care settings for older adults with disability,6 including favoring lower-quality nursing homes,7 patients and families may be dissatisfied with their options and therefore disenroll from Medicare Advantage. Switching out of MA plans may have unanticipated financial impacts on patients, given that in most states Medigap plans to supplement traditional Medicare coverage can refuse coverage to those with preexisting conditions if a person is not new to Medicare.27

While we did not directly observe the reasons for plan switching, we found that just over half of switches occurred during open enrollment, which indicates either that a person elected to switch or that their plan contract with Medicare ended, thus forcing a switch. We also found that a substantial proportion of people switched in the context of Medicaid enrollment. We were unable to determine whether people on Medicaid had greater flexibility in switching, compared to those not on Medicaid, or whether switches were driven by Medicaid status. This could be because people on Medicaid with disability are more likely to be dissatisfied with coverage limitations in Medicare Advantage, or because they are incentivized to move toward an MA plan that is integrated with their Medicaid benefits. We found higher levels of residing in an institution for switches from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage, compared to switches in the other direction. This may be because of the availability of Special Needs Plans tailored to those living in institutions, although we were unable to determine whether a person’s MA plan was a Special Needs Plan. Further qualitative work is needed to clarify the reasons and experiences of people switching plans in these varying contexts.

Our results demonstrate differential switching patterns by race and socioeconomic status. At baseline, we found that even within a cohort where everyone developed a disability, those who started in MA plans were poorer and more likely to be nonwhite than those who started in traditional Medicare. This is likely because people with lower resources are more likely to prefer the lower cost sharing in Medicare Advantage, but it also means that they are a particularly vulnerable population if their insurance coverage does not meet their needs. While nonwhite beneficiaries were more likely to switch insurance plans than white beneficiaries were, regardless of what program they started in, rates for switching out of Medicare Advantage were particularly high for nonwhite older adults. This might be partially explained by the fact that nonwhite older adults are more likely to be dually eligible and thus have the opportunity to switch out of MA outside of open enrollment.26 However, we did not find a significant relationship between Medicaid enrollment and switching. Older adults with lower incomes may prefer the lower cost sharing in Medicare Advantage when they are well, only to be surprised by or dissatisfied with MA network options or authorization procedures after they become ill. Given that prior research has demonstrated that plan characteristics such as quality star ratings are associated with switching, it is also possible that older adults who are nonwhite, from lower socioeconomic groups, or both are differentially enrolled in these low-quality plans. This may be because of individual selection into plans or because of regional variation in plan quality or availability. The role of sociodemographic characteristics in shaping experience in Medicare Advantage needs to be examined in a larger, claims-based study that could capture both race and region with more granularity than this analysis could.

Regardless of the reason for disenrollment from Medicare Advantage after disability, it is critical to monitor and understand who is switching after becoming disabled. Current risk adjustment in Medicare Advantage does not consider functional status, yet disability is associated with high health care costs and mortality, even after adjustment for diagnosis.16–20 Thus, disenrollment of disabled people from Medicare Advantage likely leads to a less costly population in the program without commensurate payment adjustments. In addition, over the past decade MA programs have expanded their coverage of home-based services such as palliative care29 that benefit older adults with disability and have increased their engagement with hospice services.30 While the CHRONIC Care Act further enables MA plans to provide nonmedical benefits, the people who need these services most might not be accessing them, if older adults with the highest levels of disability continue to leave MA plans.

One possible solution to improving the monitoring of the quality of care of older adults with disability in Medicare Advantage has been proposed by geriatric researchers: routine collection of function data across all care settings, in a form similar to but more abbreviated than the nursing home Minimum Data Set and home health Outcome and Assessment Information Set assessments that are routinely conducted and are used to determine payments.31,32 Incorporating functional measures improves accuracy in the prediction of Medicare spending and ambulatory care–sensitive hospitalizations and so would likely improve MA risk adjustment and quality measurement.33–35 However, these functional measurements could be expensive to implement broadly and prone to bias, given MA plans’ incentive to inflate functional measures.

Another promising strategy for improving the quality of Medicare Advantage for older adults with disability is to strengthen the regulatory oversight of MA plans through formal and proactive evaluation of the experience of older adults with such disability. In this vein, in 2017 the Government Accountability Office conducted an assessment of MA plans with high levels of beneficiaries’ switching to traditional Medicare, using claims to estimate the health status of individuals who switched plans.36 Consistent with our results, the assessment found significant levels of health bias, or higher rates of disenrollment by individuals in poor health. The Government Accountability Office recommended that Medicare conduct an ongoing evaluation of disenrollment by health status. Including disability as an important measure of health and conducting in-depth evaluations of the reasons that disabled patients and their families give for disenrollment would be an important step toward ensuring the provision of high-quality care within Medicare Advantage for older adults with disability.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the association between the onset of disability and switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare. While expanded regulations give Medicare Advantage the potential to better meet the needs of older adults with disability, these benefits will not be equitably distributed if older adults who have greater disability and are from lower socioeconomic and racial minority groups differentially leave MA plans. Our results indicate the potential benefit of Medicare monitoring and risk adjustment for both function and socioeconomic factors, which would be facilitated by first routinely assessing these measures throughout the health care system. The tumult that we observed in insurance coverage after disability adds to broader concern that the structure of Medicare policies does not match the needs of older adults—particularly high-need adults with disability. If efforts such as the CHRONIC Care Act to support the nonmedical needs of older adults with chronic illness in Medicare Advantage are to succeed, the structures and practices of MA plans must effectively serve older adults with disability.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was presented at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Washington, D.C., June 3, 2019. This research was supported by the National Palliative Care Research Center (Junior Investigator Award to Claire Ankuda) and the National Institute on Aging (Grant Nos. R01AG060967 to Katherine Ornstein, P30AG044281 to Kenneth Covinsky, and R01AG054540 to Amy Kelley). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Claire K. Ankuda, Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in New York City..

Katherine A. Ornstein, Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine and the Institute for Translational Epidemiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai..

Kenneth E. Covinsky, Division of Geriatrics, University of California San Francisco..

Evan Bollens-Lund, Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai..

Diane E. Meier, Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai..

Amy S. Kelley, Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai..

NOTES

- 1.Neuman P, Jacobson GA. Medicare Advantage checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Q, Trivedi AN, Galarraga O, Chernew ME, Weiner DE, Mor V. Medicare Advantage ratings and voluntary disenrollment among patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1): 70–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman M, Keohane L, Trivedi AN, Mor V. High-cost patients had substantial rates of leaving Medicare Advantage and joining traditional Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1675–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyers DJ, Belanger E, Joyce N, McHugh J, Rahman M, Mor V. Analysis of drivers of disenrollment and plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):524–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevenson DG, Huskamp HA. Integrating care at the end of life: should Medicare Advantage include hospice? JAMA. 2014;311(15):1493–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gadbois EA, Tyler DA, Shield RR, McHugh JP, Winblad U, Trivedi A, et al. Medicare Advantage control of postacute costs: perspectives from stakeholders. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(12):e386–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyers DJ, Mor V, Rahman M. Medicare Advantage enrollees more likely to enter lower-quality nursing homes compared to fee-for-service enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):78–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz ML, Kosar CM, Mroz TM, Kumar A, Rahman M. Quality of home health agencies serving traditional Medicare vs Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(9):e1910622.31483472 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Resneck JS Jr, Quiggle A, Liu M, Brewster DW. The accuracy of dermatology network physician directories posted by Medicare Advantage health plans in an era of narrow networks. JAMA Dermatol. 2014; 150(12):1290–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ankuda CK, Levine DA, Langa KM, Ornstein KA, Kelley AS. Caregiving, recovery, and death after incident ADL/IADL disability among older adults in the United States. J App Gerontol. 2019. February 10. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith AK, Walter LC, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Covinsky KE. Disability during the last two years of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2013; 173(16):1506–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Disability and care needs among older Americans. Milbank Q. 2014;92(3): 509–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He S, Craig BA, Xu H, Covinsky KE, Stallard E, Thomas J 3rd, et al. Unmet need for ADL assistance is associated with mortality among older adults with mild disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(9): 1128–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen SM, Piette ER, Mor V. The adverse consequences of unmet need among older persons living in the community: dual-eligible versus Medicare-only beneficiaries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014; 69(Suppl 1):S51–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Depalma G, Xu H, Covinsky KE, Craig BA, Stallard E, Thomas J 3rd, et al. Hospital readmission among older adults who return home with unmet need for ADL disability. Gerontologist. 2013;53(3):454–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inouye SK, Peduzzi PN, Robison JT, Hughes JS, Horwitz RI, Concato J. Importance of functional measures in predicting mortality among older hospitalized patients. JAMA. 1998; 279(15):1187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4): 559–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reichard A, Gulley SP, Rasch EK, Chan L. Diagnosis isn’t enough: understanding the connections between high health care utilization, chronic conditions, and disabilities among U.S. working age adults. Disabil Health J. 2015;8(4):535–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landi F, Liperoti R, Russo A, Capoluongo E, Barillaro C, Pahor M, et al. Disability, more than multimorbidity, was predictive of mortality among older persons aged 80 years and older. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):752–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, Du Q, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA. Determinants of medical expenditures in the last 6 months of life. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(4):235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willink A, DuGoff EH. Integrating medical and nonmedical services—the promise and pitfalls of the CHRONIC Care Act. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(23):2153–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laschober M Estimating Medicare advantage lock-in provisions impact on vulnerable Medicare beneficiaries. Health Care Financ Rev. 2005; 26(3):63–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montaquila J, Freedman VA, Edwards B, Kasper JD. National Health and Aging Trends Study (NHATS) round 1 sample design and selection [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2012. May 10 [cited 2019 Dec 20]. (NHATS Technical Paper No. 1). Available from: https://www.nhats.org/scripts/sampling/NHATS_Round1_Sample_Design_05_10_12.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC. Classification of persons by dementia status in the National Health and Aging Trends Study [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2013. July [cited 2019 Dec 20]. (Technical Paper No. 5). Available from: http://www.nhats.org/scripts/documents/NHATS_Dementia_Technical_Paper_5_Jul2013.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky KE, Ritchie CS, Federman AD, Roberts L, et al. Epidemiology of the homebound population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(7):1180–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medicare.gov. Special circumstances (Special Enrollment Periods) [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [cited 2019 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.medicare.gov/sign-up-change-plans/when-can-i-join-a-health-or-drug-plan/special-circumstances-special-enrollment-periods [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyers DJ, Trivedi AN, Mor V. Limited Medigap consumer protections are associated with higher re-enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019; 38(5):782–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grabowski DC, Joyce NR, McGuire TG, Frank RG. Passive enrollment of dual-eligible beneficiaries into Medicare and Medicaid managed care has not met expectations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5): 846–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olson A, Harker M, Saunders R, Taylor DH Jr. Innovations in Medicare Advantage to improve care for seriously ill patients [Internet]. Washington (DC): Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy; 2018. July [cited 2019 Dec 20]. Available from: https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/sites/default/files/atoms/files/innovations_in_medicare_advantage_to_improve_care_for_seriously_ill_patients.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teno JM, Christian TJ, Gozalo P, Plotzke M. Proportion and patterns of hospice discharges in Medicare Advantage compared to Medicare fee-for-service. J Palliat Med. 2018; 21(3):302–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hittle DF, Shaughnessy PW, Crisler KS, Powell MC, Richard AA, Conway KS, et al. A study of reliability and burden of home health assessment using OASIS. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2004;22(4):43–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.CMS.gov. MDS 3.0 Frequency Report [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [last modified 2019 Nov 17; cited 2019 Dec 20]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Public-Reports/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Frequency-Report.html [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston KJ, Joynt Maddox KE. The role of social, cognitive, and functional risk factors in Medicare spending for dual and nondual enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(4):569–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnston KJ, Wen H, Schootman M, Joynt Maddox KE. Association of patient social, cognitive, and functional risk factors with preventable hospitalizations: implications for physician value-based payment. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(8): 1645–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnston KJ, Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Joynt Maddox KE. Association between patient cognitive and functional status and Medicare total annual cost of care: implications for value-based payment. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1489–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Government Accountability Office. Medicare Advantage: CMS should use data on disenrollment and beneficiary health status to strengthen oversight [Internet]. Washington (DC): GAO; 2017. April [cited 2019 Dec 20]. (GAO Report No. GAO-17–393). Available from: https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/684386.pdf [Google Scholar]