Abstract

Rather than degree of stenosis, assessing plaque structure and composition is relevant to discerning risk for plaque rupture with downstream ischemic event. The structure and composition of carotid plaque has been assessed noninvasively using Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) ultrasound imaging. In particular, ARFI-derived peak displacement (PD) estimations have been demonstrated for discriminating soft (lipid rich necrotic core (LRNC) or intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH)) from stiff (collagen (COL) or calcium (CAL)) plaque features; however, PD did not differentiate LRNC from IPH or COL from CAL. The purpose of this study is to evaluate a new ARFI-based measurement, the variance of acceleration (VoA), for differentiating among soft and stiff plaque components. Both PD and VoA results were obtained in vivo for a human carotid plaque acquired in a previous study and matched to a histological standard analyzed by a pathologist. With VoA, plaque feature contrast was increased by an average of 60% in comparison to PD.

I. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the world’s primary cause of death [1]. It is characterized by the development of atheromatous plaque in the walls of arteries that feed vital organs, i.e. heart or brain. This disease usually presents a lack of symptoms and can result in a heart attack or stroke. However, recent histological studies have shown that plaques at a high rupture risk have particular characteristics, including the presence of a thin fibrous cap (FC), lipid-rich necrotic core (LRNC) and inflammatory cells with intraplaque hemorrhage (IPH) [2–4]. This information reveals that the composition of a plaque may be a better biomarker than its degree of stenosis towards assessing plaque rupture risk.

Among many approaches, conventional B-Mode ultrasound is currently the most widely applied diagnostic modality for atherosclerosis, due to its real-time nature, portability, and capability of detecting stenosis [5]. Unfortunately, B-Mode relies on microscopic properties of tissues, and does not provide efficient reliability when characterizing plaque composition [6].

Another ultrasound-based imaging method, Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) imaging, interrogates elastic properties by measuring tissue displacement in response to an impulsive mechanical excitation. In previous studies, we have shown that ARFI-derived peak displacement (PD) differentiates soft plaque areas (i.e. LRNC or IPH) from stiff regions (i.e. collagen (COL) or calcium (CAL)) in a preliminary clinical study [7, 13, 15]. However, ARFI PD had low sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing between soft and between stiff elements.

Other groups have shown that differentiating among soft and stiff features is diagnostically relevant. In the case of soft plaque areas, MRI studies have shown that the presence of IPH implies higher risk for ischemic events compared to individual presence of LRNC [8]. In regard to stiff areas, the presence of large calcium deposits can stabilize plaques, whereas small deposits can be destabilizing depending on their position [9]. The calcification location relative to other structures becomes vital. Therefore, accurately differentiating IPH from LRNC and CAL from COL is highly diagnostically relevant in atherosclerosis imaging.

To improve discrimination of LRNC from IPH and CAL from COL in ARFI imaging, our group is developing a new ARFI-based metric - variance of acceleration (VoA). This new metric was originally developed in ARFI Surveillance of Subcutaneous Hemorrhage (ASSH) imaging, a method for noninvasively detecting and monitoring subcutaneous bleeding [10]. The main application for ASSH imaging up to now has been monitoring subcutaneous hemorrhage in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary catheterization [11]. We now apply the same fundamental principle underlying ASSH imaging: that high displacement measurement variance (jitter), which arises from tissue regions with high decorrelation and/or low SNR [12], can be exploited to differentiate tissue types. In this manner, it is the variance over ensemble time in ARFI displacement profiles, rather than the magnitude of ARFI-induced displacements, that is exploited. To amplify displacement measurement variance, we evaluate the displacement profiles’ second time derivative (a high-pass filtering operation), or the ‘acceleration’ profiles. Thus, the analyzed parameter in this approach is the variance of acceleration (VoA).

In this study, VoA is compared to PD for discriminating LRNC, IPH, COL and CAL in a representative plaque. The example plaque was originally imaged by ARFI in vivo as part of a previous clinical study involving 25 patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy (CEA) [13]. Here, as in the previous study, plaque component delineation by VoA and PD is validated against spatially-matched histology. The overall goal of this analysis is to determine if VoA improves discrimination between soft (LRNC and IPH) and between stiff (COL and CAL) plaque features.

II. Methods

A. In vivo patient imaging

Patients undergoing CEA were recruited from UNC Hospitals following the protocol in [13]. Institutional review board approval was obtained and an informed consent was given from each participant. One representative dataset from one CEA patient (53 y/o, female, BMI: 26.7 kg/m2, symptomatic, diastolic blood pressure: 74 mmHg) was analyzed for this study.

The raw radiofrequency data from the carotid plaque used in this study was acquired as described in [13] using a Siemens Acuson Antares imaging system (Siemens Medical Solutions USA) and a VF7-3 linear array. For ARFI imaging, excitation pulses had a frequency of 4.21 MHz and a 300-cycle length, tracking pulses had a frequency of 6.15 MHz and a length of two cycles. Data were acquired during diastole using electrocardiogram gating. Estimations of VoA and PD were made using custom software written in MATLAB (Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA).

B. ARFI VoA Estimation

First, axial displacements were measured using onedimensional normalized cross correlation in order to generate displacement profiles over ensemble time, as described in [14]. From these profiles, PD was calculated as the maximum displacement amplitude at any time point during ensemble time, as described in [14]. Also, VoA was calculated as the variance of the second time derivative per pixel through ensemble time,

where N is the total number of frames, x and y represent the axial and lateral coordinates, respectively, tk is a time kernel with a size of five frames (0.5 ms given the 10 kHz PRF), and μ is the acceleration mean through time per pixel. Acceleration is calculated by

where d(x,y, t) is the displacement profile through ensemble time.

Parametric VoA images were rendered by computing the variance for one tk of size 20, i.e. the last 20 frames per sample. For both VoA and PD images, values were normalized using the mean value within the plaque and a range of two standard deviations.

C. Intraplaque structure analysis

The intact plaque specimen extracted during CEA was imaged with volumetric micro-CT. The CT image was segmented into calcium and soft tissue, and calcium deposits and vessel morphology on the micro-CT volume were aligned with calcium deposits and morphology on the B-Mode frame (acquired simultaneously with ARFI data) to identify the proper sectioning plane to achieve spatial alignment of ARFI and histology data. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), Von Kossa (VK) for calcium, and Lillie’s Masson’s Trichrome (LMT) for collagen.

The plaque region was delineated on histology sections by a pathologist specialized in atherosclerosis, who was blinded to the ARFI imaging results. The pathologist examined and segmented digitized histology slides into regions of COL, CAL, LRNC, FC, and IPH [13]. These regions were used in the calculation of feature contrast, computed as

where μ is the mean of the selected regions of interest (ROIs), and the subscripts p and b refer to the analyzed feature and background regions, respectively.

III. Results

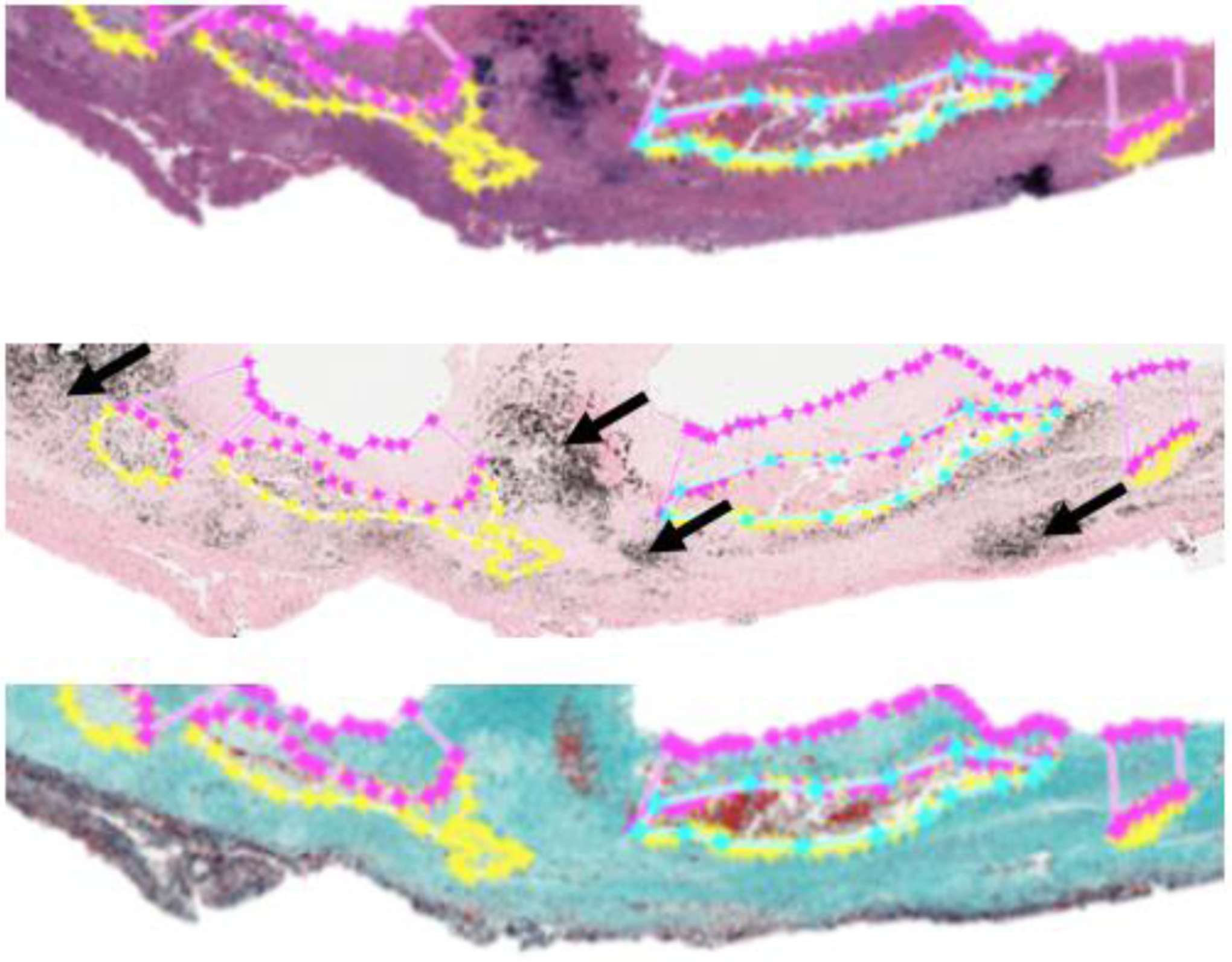

For the representative plaque example, histology sections are shown in Figure 1. The pathologist identified IPH (cyan), FC (magenta), LRNC (yellow), and CAL (black arrows).

Figure 1.

HE (Top), VK (Middle), and LMT (Bottom) stained sections of a sample carotid plaque.

The corresponding B-Mode image for this plaque is shown in Figure 2. Recall that B-Mode and ARFI imaging were performed in vivo prior to CEA, and the CEA specimen was harvested for histological validation of ARFI outcomes. Arrows on the B-Mode indicate calcium deposits, which were also observable in volumetric micro-CT images of the sample acquired prior to sectioning. The micro-CT images were aligned to the B-Mode plane using the calcium deposits and plaque morphology as fiducial markers, and the registered micro-CT volume was then used to identify the sectioning plane to achieve spatial alignment with B-Mode and ARFI imaging [13].

Figure 2.

B-Mode image of a sample carotid plaque. Arrows indicate calcum deposits.

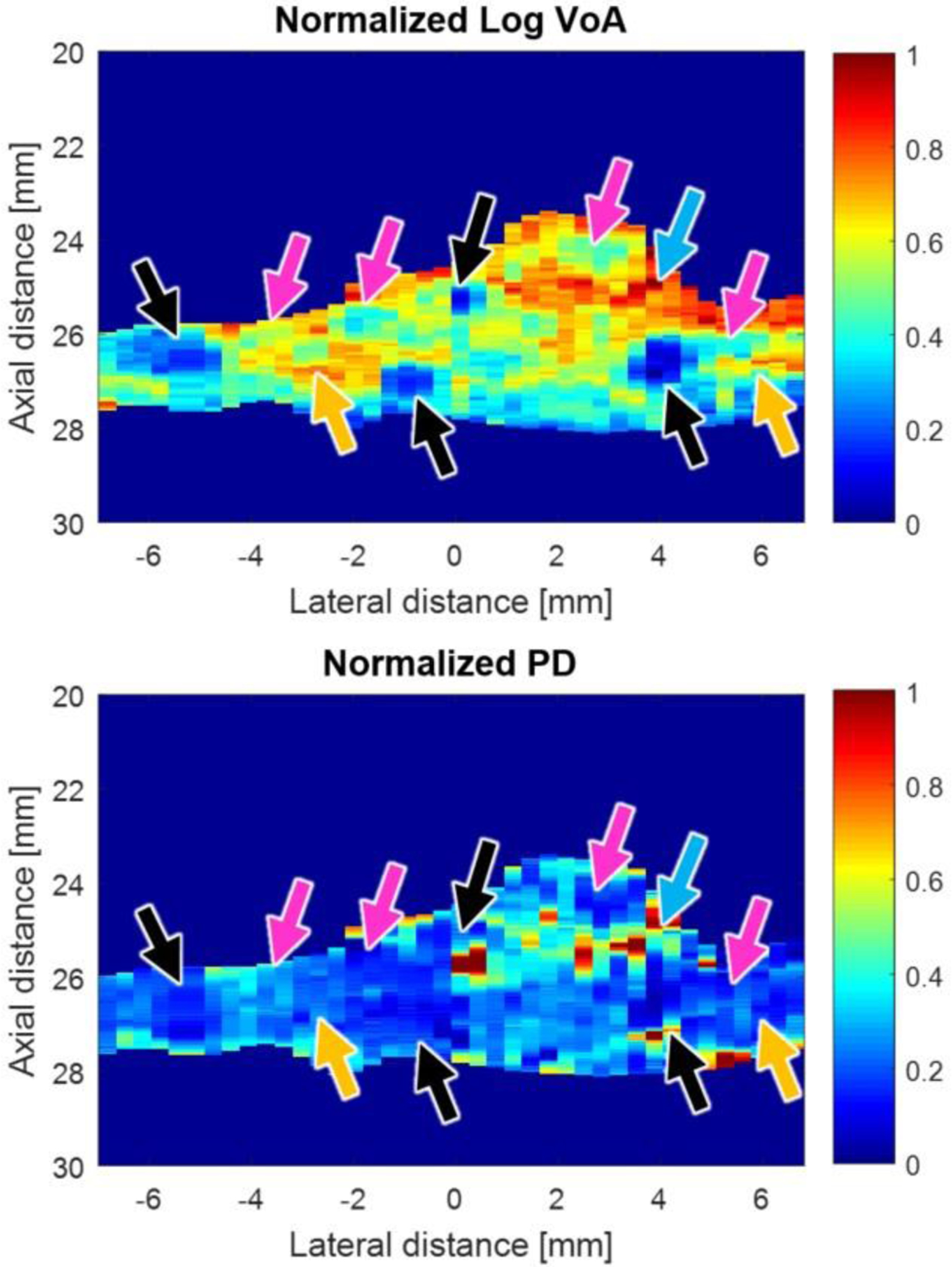

Parametric normalized ARFI VoA images were rendered and compared to parametric normalized ARFI PD images. Figure 3 shows both VoA and PD images for the plaque example.

Figure 3.

Normalized log VoA (Top) and normalized PD-ARFI (bottom) ROI images of a sample carotid plaque. The following features are indicated by the arrows: cAl (black), COL (magenta), IPH (cyan) and LRNC (yellow).

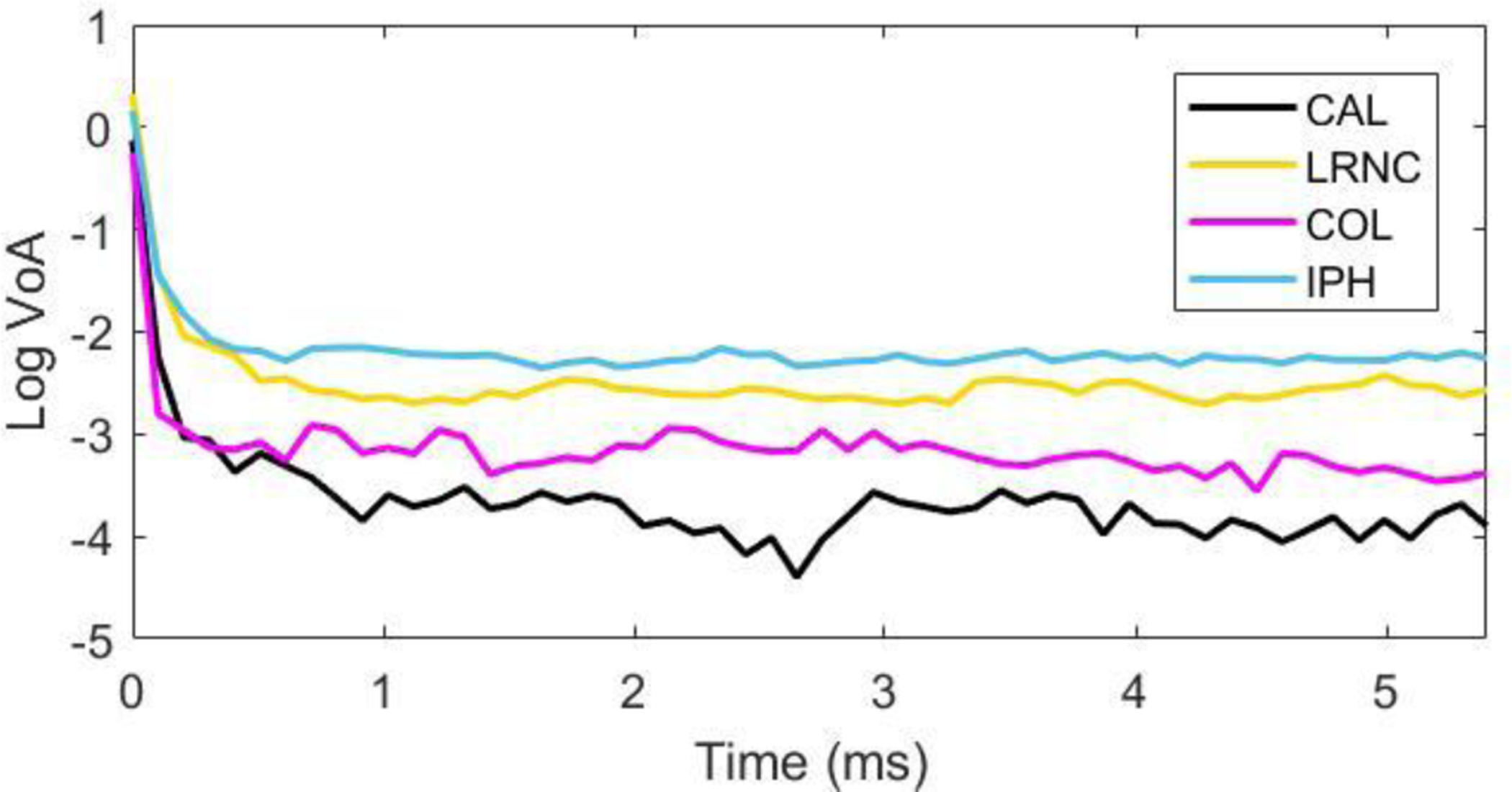

Pathologist markings of LRNC, IPH, COL and CAL on histology images were used to segment the plaque features in both the VoA and PD images in Figure 3. Figure 4 shows VoA versus ensemble time per plaque feature. In the case of soft features, IPH has a VoA magnitude that is higher than LRNC by 25% (p< 0.0001), whereas in the case of stiff features, COL has a higher VoA magnitude than CAL by 45% (p< 0.0001). Contrast results are shown in Table I.

Figure 4.

Log VoA (bottom) versus ensemble time for four plaque features.

TABLE I.

Contrast Between Soft and Stiff Regions

| Intraplaque Region | VoA | PD-ARFI |

|---|---|---|

|

Soft (IPH - LRNC) |

0.87 ± 0.18 | 0.37 ± 0.27 |

|

Stiff (CAL – COL) |

1.58 ± 0.21 | 0.88 ± 0.54 |

IV. Discussion

The estimation of a new parameter, VoA, through ARFI imaging is presented in this study for improving carotid plaque characterization. For this parameter, acceleration is calculated because it is a second time derivative, which is a high pass filtering operation. The high pass filter serves to amplify variance in the displacement estimate, which is elevated in regions of higher signal decorrelation and/or lower signal amplitude.

Figure 3 shows, by visual inspection, that CAL and IPH are discriminated as regions of relatively low and high VoA, respectively, in parametric VoA images. Calcium and IPH are not as well delineated in the corresponding PD image. Figure 4 presents VoA versus ensemble time for each plaque feature. The VoA values for IPH and LRNC were statistically significantly different, as were the VoA values for COL and CAL (Wilcoxon rank sum test, p< 0.0001 for each case).

Notably, like PD, VoA depends on the applied ARF magnitude because larger forces will yield bigger displacements and thus greater signal decorrelation. As such, VoA and PD are both suitable for qualitative analysis of plaque features, and the normalized plaque images in Figure 3 highlight relative variations in VoA and PD.

In terms of contrast, the difference between IPH and LRNC is more accentuated than between CAL and COL. For both soft and stiff regions, contrast was higher for VoA than for PD by an average of 70% and 50%, respectively.

In future work, VoA will be more fully assessed for delineating plaque features in a blinded reader study. Further, we will perform statistical analyses of sensitivity vs. specificity, and assess VoA’s clinical relevance for diagnosis by evaluating a sufficiently powered group size. We will also investigate the relevance of VoA to improving delineation of the plaque/lumen boundary. Finally, post-processing techniques will be applied to automate plaque feature segmentation.

V. Conclusion

This study presented a new ARFI-based parameter, VoA, in application to characterizing plaque structure and composition. VoA was compared to ARFI-derived PD in a representative in vivo human carotid plaque containing LRNC, IPH, COL, and CAL deposits. VoA improved discrimination of IPH from LRNC and CAL from COL relative to PD. The results show that VoA has potential for improving discrimination of different plaque features that convey vulnerability for rupture.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by NIH grants R01HL092944, K02HL105659, and T32HL069768.

Contributor Information

Gabriela Torres, Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University, NC, USA.

Tomasz J. Czernuszewicz, Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University, NC, USA.

Jonathon W. Homeister, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Mark A. Farber, Department of Surgery, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Caterina M. Gallippi, Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and North Carolina State University, NC, USA.

References

- [1].Mendis S, Puska P, Norrving B, “Global Atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control,” World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Van Mieghem C, McFadden EP, Feyter PJ, “Noninvasive detection of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis coupled with assessment of changes in plaque characteristics using novel invasive imaging modalities,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 47 (6): 1134–1142, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Moreno PR, “Vulnerable plaque: definition, diagnosis, and treatment,” Cardiol. Clin vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 1–30, February. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Stary HC, “Natural history and histological classification of atherosclerotic lesions: an update,” Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 1177–1178, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Heiss G, Sharrett AR, Barnes R, R., Chambless LE, Szklo M, Alzola C, “Carotid atherosclerosis measured by B-mode ultrasound in populations: associations with cardiovascular risk factors in the ARIC study,” American journal of epidemiology, 134(3), pp.250–256, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].ten Kate GL, Sijbrands EJ, Staub D, Coll B, ten Cate FJ, Feinstein SB, Schinkel AFL, “Noninvasive imaging of the vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque.,” Curr. Probl. Cardiol, vol. 35, no. 11, pp. 556–91, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Czernuszewicz TJ, Homeister JW, Caughey MC, Farber MA, Fulton JJ, Ford PF, Marston WA, Vallabhaneni R, Nichols TC, Gallippi CM, “In vivo carotid plaque stiffiess measurements with ARFI ultrasound in endarterectomy patients,” in Proceedings of the IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kate GL, Sijbrands EJ, Staub D, “Noninvasive imaging of the vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque,” Curr. Probl. Cardiol, 35:556–91, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Redgrave JNE, Lovett JK, Gallagher PJ, “Histological assessment of 526 symptomatic carotid plaques in relation to the nature and timing of ischemic symptoms: the Oxford plaque study,” Circulation, 113:2320–8, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Geist RE, Gallippi CM, Nichols TC, Merricks EP, Caughey MC, “In vivo ARFI surveillance of subcutaneous hemorrhage (ASSH) for monitoring rcFVIII dose response in hemophilia A dogs,” in Proceedings of the IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, pp. 2296–2299, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Geist RE, DuBois CH, Nichols TC, Caughey MC, Merricks EP, Raymer R, Gallippi CM, “Experimental Validation of ARFI Surveillance of Subcutaneous Hemorrhage (ASSH) Using Calibrated Infusions in a Tissue-Mimicking Model and Dogs,” Ultrasonic imaging, 38(5), pp.346–358, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Walker WF, Trahey GE, “A fundamental limit on delay estimation using partially correlated speckle signals,” IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control, 42(2), pp.301–308, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Czernuszewicz TJ, Homeister JW, Caughey MC, Farber M. a., Fulton JJ, Ford PF, Marston W. a., Vallabhaneni R, Nichols TC, and Gallippi CM, “Non-invasive in Vivo Characterization of Human Carotid Plaques with Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Ultrasound: Comparison with Histology after Endarterectomy,” Ultrasound Med. Biol, vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 685–697, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pinton GF, Dahl JJ, and Trahey GE, “Rapid tracking of small displacements with ultrasound.” IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control, vol. 53, no. 6, pp. 1103–1117, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Czernuszewicz TJ, Homeister JW, Caughey MS, Wang Y, Zhu H, Huang BY, Lee ER, Zamora CA, Farber MA, Fulton JJ, Ford PF, Marston WA, Vallabhaneni R, Nichols TC, Gallippi CM, “Performance of Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Ultrasound Imaging for Carotid Plaque Characterization with Histological Validation”, Journal of Vascular Surgery, in press, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]