Abstract

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) are critically involved in various learning mechanisms including modulation of fear memory, brain development and brain disorders. While NMDARs mediate opposite effects on medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) interneurons and excitatory neurons, NMDAR antagonists trigger profound cortical activation. The objectives of the present study were to determine the involvement of NMDARs expressed specifically in excitatory neurons in mPFC-dependent adaptive behaviors, specifically fear discrimination and fear extinction. To achieve this, we tested mice with locally deleted Grin1 gene encoding the obligatory NR1 subunit of the NMDAR from prefrontal CamKIIα positive neurons for their ability to distinguish frequency modulated (FM) tones in fear discrimination test. We demonstrated that NMDAR-dependent signaling in the mPFC is critical for effective fear discrimination following initial generalization of conditioned fear. While mice with deficient NMDARs in prefrontal excitatory neurons maintain normal responses to a dangerous fear-conditioned stimulus, they exhibit abnormal generalization decrement. These studies provide evidence that NMDAR-dependent neural signaling in the mPFC is a component of a neural mechanism for disambiguating the meaning of fear signals and supports discriminative fear learning by retaining proper gating information, viz. both dangerous and harmless cues. We also found that selective deletion of NMDARs from excitatory neurons in the mPFC leads to a deficit in fear extinction of auditory conditioned stimuli. These studies suggest that prefrontal NMDARs expressed in excitatory neurons are involved in adaptive behavior.

Keywords: Fear discrimination learning, Fear extinction, NMDAR, Medial prefrontal cortex

1. Introduction

Normal brain functioning relies critically on the ability to keep fear memories distinct and resistant to confusion. Fear behavior is controlled by adaptive processes including discrimination, generalization and extinction, which are likely regulated by separate neural mechanisms. While fear memory accuracy is critical for survival and balanced fear generalization allows avoidance of dangerous situations, circuit and molecular level mechanisms for fear discrimination remain unclear. Multiple memory systems theory postulates that different types of memory are consolidated via hardwired pathways (Squire, 1992). In tone fear conditioning, tone [conditional stimulus (CS)]-foot shock [unconditional stimulus (US)] associations are directly encoded through synaptic plasticity in the amygdala, which receives direct auditory inputs (Medina, Repa, Mauk, & LeDoux, 2002). During contextual fear conditioning, the contextual stimulus (CS) is encoded by the dorsal hippocampus, whose outputs are subsequently associated with the US through synaptic plasticity in the amygdala (Kim & Fanselow, 1992; Maren & Fanselow, 1995), and later consolidated by the hippocampal–prefrontal circuitry (Frankland & Bontempi, 2005; Frankland, Bontempi, Talton, Kaczmarek, & Silva, 2004; Quinn, Ma, Tinsley, Koch, & Fanselow, 2008; Tse et al., 2011; Zelikowsky et al., 2013). In fact, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) can compensate for the absence of the dorsal hippocampus in contextual fear learning (Zelikowsky et al., 2013). In addition, fear behavior is differentially regulated by the infralimbic (IL) and prelimbic (PL) subregions of the mPFC (Courtin, Bienvenu, Einarsson, & Herry, 2013; Quirk & Mueller, 2008; Sierra-Mercado, Padilla-Coreano, & Quirk, 2010; Sotres-Bayon, Cain, & LeDoux, 2006) via fear excitation and inhibition, respectively (Sierra-Mercado et al., 2010; Sotres-Bayon & Quirk, 2010), which may be due to differential connectivity with the amygdala (Gabbott, Warner, Jays, Salway, & Busby, 2005; Vertes, 2004). For example, differential conditioning increases unit and field responses within the amygdala to the conditioned stimulus, paired with US (CS+), whereas responses to the second stimulus that was never paired with US (CS−) decreased (Collins & Pare, 2000).

Studies show that mPFC lesions enhance generalization. In absence of the IL mPFC, rats become more fearful of a novel environment after fear conditioning (Zelikowsky et al., 2013). In addition, lesions of the mPFC disrupts discrimination of more discrete multiple odor stimuli (DeVito, Lykken, Kanter, & Eichenbaum, 2010). Furthermore, inactivation of pathways (in either direction) between the mPFC and the nucleus reuniens of the thalamus (NR) enhances fear memory generalization (Xu & Sudhof, 2013; Xu et al., 2012). We have recently demonstrated that prefrontal hypofunction of transcription regulators implicated in the mechanism underlying long-term memory consolidation results in abnormal generalization decrement during contextual and auditory fear discrimination learning in mice (Vieira et al., 2014). These data indicate that the prefrontal circuit might be involved in fear discrimination between the conditioned stimulus CS+ (reinforced with a foot shock) and CS− (nonreinforced).

There is strong evidence for prefrontal N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) in the mechanism underlying extinction of conditioned fear (Burgos-Robles, Vidal-Gonzalez, Santini, & Quirk, 2007; Santini, Muller, & Quirk, 2001). While fear extinction is widely considered as a new learning event rather than forgetting (Maren & Quirk, 2004), it is postulated that fear extinction involves inhibition of an existing response (Bouton & Nelson, 1994). In agreement with the data showing that lesions in the mPFC produce a deficit in extinction of conditioned fear (Gewirtz, Falls, & Davis, 1997; Morgan, Romanski, & LeDoux, 1993; Orsini, Kim, Knapska, & Maren, 2011; Orsini & Maren, 2012; Quirk, Russo, Barron, & Lebron, 2000), consolidation of fear extinction memory recruits mechanisms controlled by NMDARs, mitogen-activated protein kinase and protein synthesis (Quirk & Mueller, 2008; Sotres-Bayon, Diaz-Mataix, Bush, & LeDoux, 2009). Involvement of NMDARs in a mPFC-dependent learning mechanism is supported by the studies showing that NMDARs are effective mediators of synaptic plasticity in prefrontal excitatory neurons [e.g. (Hirsch & Crepel, 1991)]. However, NMDARs in the mPFC mediate opposite effects on interneurons and excitatory neurons (Homayoun & Moghaddam, 2007). Pharmacological blockers of NMDAR trigger profound cortical activation in behaving rodents (Jackson, Homayoun, & Moghaddam, 2004) and human volunteers (Breier et al., 1997; Lahti, Holcomb, Medoff, & Tamminga, 1995; Suzuki, Jodo, Takeuchi, Niwa, & Kayama, 2002; Vollenweider, Leenders, Oye, Hell, & Angst, 1997) suggesting that the effect of NMDAR antagonists in pharmacological studies is predominately targeted to inhibitory neurons producing disinhibition of excitatory network. The objectives of the present study were to determine the involvement of NMDARs expressed specifically in CamKIIα positive excitatory neurons in mPFC-dependent adaptive behaviors, specifically fear discrimination and fear extinction.

Based on the studies discussed above, discrimination between dangerous, fear-conditioned CS+ and nonreinfoced CS− auditory cues likely involves mPFC functional interactions. Still unknown are the neural mechanisms underlying the attainment of fear memory accuracy for appropriate discriminative responses to CS+ and CS− stimuli. To explore the potential impact of prefrontal NMDARs on fear discrimination, we generated mutant mice with locally deleted obligatory subunit of the NMDAR in prefrontal excitatory CamKIIα positive neurons and examined their capability to distinguish between a dangerous, fear-conditioned stimulus and a nonreinforced stimulus in a fear discrimination procedure. For behavioral evaluations, we used an auditory fear discrimination task that depends on the ability to distinguish discrete auditory cues constructed of frequency modulated (FM) upward or downward tone sweeps. This auditory fear discrimination task indicated that NMDAR-dependent neural signaling within mPFC circuitry is an important component of the mechanism for disambiguating the meaning of fear signals. We have also demonstrated that NMDAR inactivation in prefrontal excitatory neurons impairs fear extinction.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

The UC Riverside Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures in accordance with the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. We used C57BL/6J mice for all experiments. Mice were weaned at postnatal day 21, housed 4 animals to a cage with same sex littermates with ad libitum access to food and water and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle. Old bedding was exchanged for fresh autoclaved bedding every week.

2.2. Surgery

We used the same rescue surgery protocol as described previously (Vieira et al., 2014) Briefly, 2–3-month-old mice were separated into individual cages prior to surgery. Anesthesia was induced by placing individual mice in a chamber filled with isoflurane. After induction, anesthesia was maintained by mounting the mouse in a heated stereotaxic apparatus and supplying a constant flow of isoflurane/oxygen mix. After adjusting the ear bars, bite bar, and nose clamp, the scalp was shaved, sanitized, and incised along the midline. A dental drill was used to thin the skull over the injection sites. The thinned bone was then removed with a needle tip. A 5-μl calibrated glass micropipette [8 mm taper, 8 μm internal tip diameter] was fitted with a plastic tube connected to a 10-ml syringe and lowered onto a square of Parafilm containing a 4-μl drop of virus. After filling the micropipette, it was lowered to the proper stereotaxic coordinates and pressure was applied to the syringe to inject 0.7 μl of solution at a rate of 50 nl/min. After completing the bilateral injection and removing the micropipette, the skin was sutured and antibiotic was applied to the scalp. The mouse was kept warm by placing its cage on a heated plate and injected with buprenorphine [0.05 mg/kg] for pain relief. The water bottle in the cage was mixed with meloxicam [1 mg/kg] to relieve pain during subsequent recovery days. Animals were monitored for any signs of distress or inflammation for 3 days after surgery. Behavioral experiments were initiated 3 days after surgery. The mPFC was targeted at the following stereotaxic coordinates: Bregma; AP 1.8, ML ± 0.4, DV 1.4.

2.3. Viruses

Surgical procedures were standardized to minimize the variability of HSV virus injections, using the same stereotaxic coordinates for the mPFC and the same amount of HSV injected into the mPFC for all mice. CRE and/or mCherry under control of CamKIIα Promoter were cloned into the HSV amplicon and packaged using a replication-defective helper virus as previously described (Lim & Neve, 2001; Neve & Lim, 2001). The viruses were prepared by Dr. Rachael Neve (MIT, Viral Core Facility). The average titer of the recombinant virus stocks was typically 4.0 × 107 infectious units/ml. HSV viruses are effectively expressed in neurons in the PFC.

2.4. Behavioral assays

All behavioral experiments were performed under blind conditions.

2.4.1. Fear conditioning

All fear conditioning was performed in a fear conditioning box (Coulburn Instruments Inc.) located in a sound attenuated chamber and analyzed automatically by a Video-based system (Freeze Frame software ActiMetrics Inc.). Freezing was expressed as “% Freezing”, which was calculated as a percent of freezing time per total time spent in the testing chamber or time window during which the CS was presented. The chamber was cleaned in between trials with Quatracide, 70% ethanol, and distilled water.

2.4.2. Auditory discrimination

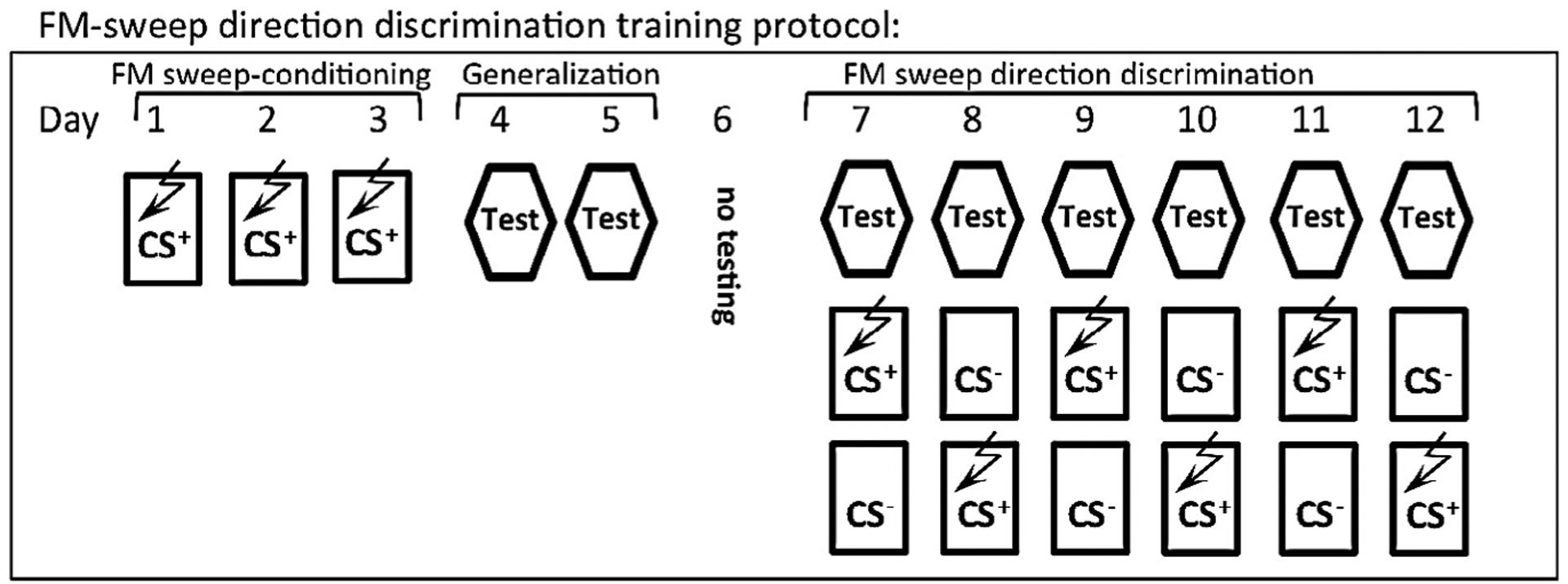

The FM-sweep direction fear discrimination task was performed according to a previously described protocol (Vieira et al., 2014) (see Fig. 2). This task is divided into three phases: FM-sweep conditioning, generalization test and discrimination phase (Fig. 2). The conditioned stimuli (CS) were 20 s trains of frequency modulated (FM)-sweeps for a 400 ms duration, logarithmically modulated between 2 and 13 kHz (upsweep) or 13 and 2 kHz (downsweep) delivered at 1 Hz at 75 dB. While the CS+(conditioned upsweep or conditioned downsweep) was paired with a foot shock (2 s, 0.75 mA), the CS− (upsweep or downsweep) was never reinforced with a foot shock. The onset of the US coincided with the onset of the last sweep for the CS. The assignment of the FM stimuli to CS+ or CS− was counterbalanced between subjects. For fear conditioning acquisition (days 1–3; initial training phase), the animals were presented with a single CS–US pairing per day. The FM-sweep Fear Retrieval (day 4) and Generalization (day 4–5) were tested during so called “Test” (Fig. 2) in context C. “Test” involved measurements of freezing to 3 × CS− for 30 s and 3 × 30 s CS+ without US presented after 3 min baseline and with 3 min inter trial intervals (ITI). During “Test”, both CS+ and CS− were not reinforced with US and CS+/CS− stimuli were presented in alternated, counterbalanced order. Context C was significantly different from the training chamber (context A), in which animals displayed low context baseline freezing (Jacobs, Cushman, & Fanselow, 2010). The discrimination phase of FM sweep direction discrimination training was performed over three sessions a day for 6 days (days 7–12): Session 1 was the performance test (“Test”), Session 2 was the presentation to CS+ paired with US (or CS−) after 3 min in Context A, and Session 3 was the presentation to the CS− (or CS+ paired with US) after 3 min in Context A. CS+ and CS− presentation order was counterbalanced.

Fig. 2.

FM-sweep direction fear discrimination training protocol. (A) Schematic of the auditory fear discrimination protocol (see Methods). Following 3 days of paired FM sweep-foot shock training, a generalization test assessed the levels of freezing in response to the non-reinforced stimulus compared to the conditioned stimulus. Generalization was followed by 6 days of discrimination training (Days 7–12) in which each day consists of 3 sessions: a non-reinforced test of freezing to CS+ and CS− (“Test”), a CS+ and US pairing, and a non-reinforced CS− session (CS+ and CS− order was counterbalanced). The conditioned stimuli (CS) for auditory fear conditioning were 20 s trains of FM-sweeps for a 400 ms duration, logarithmically modulated between 2 and 13 kHz (upsweep) or 13 and 2 kHz (downsweep) delivered at 1 Hz at 75 dB. “Test” indicates performance assessment. During “Test” 3 CS+ and 3 CS− (30 s each) were presented after 180 s freezing baseline recording and with 180 s ITI. The assignment of the stimuli to CS+ or CS− (and order) was counterbalanced between subjects.

2.4.3. Fear extinction

This task is divided into two phases: FM-sweep conditioning and fear extinction phase. The conditioned stimuli (CS+) were 20-s trains of frequency modulated (FM)-sweeps for a 400-ms duration, logarithmically modulated between 2 and 13 kHz (upsweep) or 13 and 2 kHz (downsweep) delivered at 1 Hz at 75 dB. While the CS+ was paired with a foot shock (2 s, 0.75 mA), the CS− (upsweep or downsweep) was never reinforced. The assignment of the stimuli to CS+ or CS− was counterbalanced between subjects. For fear conditioning acquisition, the animals were presented with three CS–US pairings with 3 min ITI. Fear extinction involves following 7 days of trainings (Fig. 4A, Day 2–8) in Context C (see above). Each day, 3 × 30 s CS− and 3 × 30 s CS+ are presented after 3 min baseline and with 3 min ITI. Both CS+ and CS− were not reinforced during extinction and stimuli are presented in alternated, counterbalanced order.

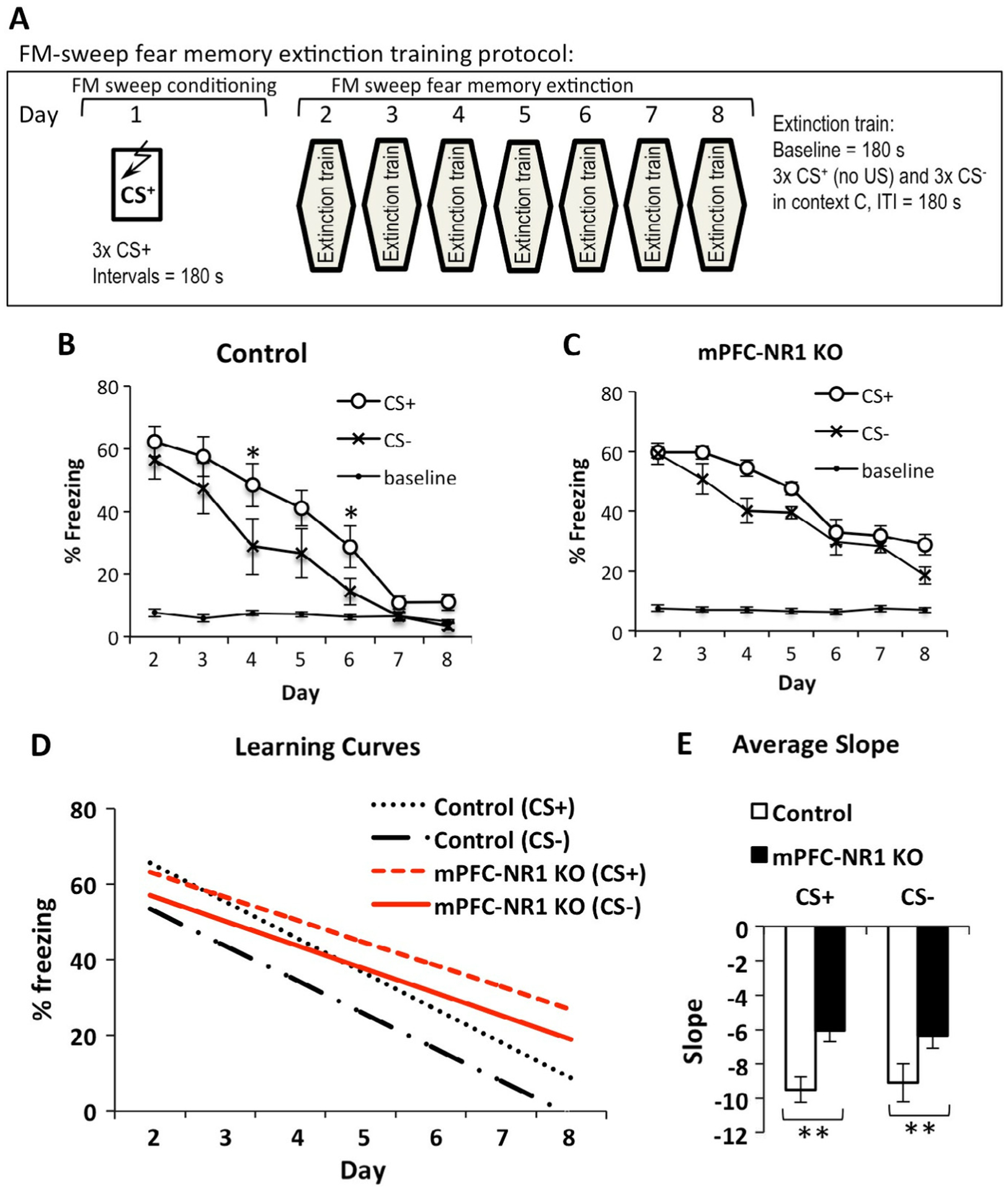

Fig. 4.

mPFC-NR1 KO mice show deficient fear memory extinction. (A) Experimental design for the extinction protocol. A single day of training in which the animal receives 3 pairings of upward sweeping FM tones and foot shock is followed by 7 days of extinction in which freezing is measured during the presentation of 3 × CS− (downward sweeping FM tones) followed by 3 × CS+(unpaired with foot shock) in a separate context from training (Context C). (B) Percent of total time spent freezing during the sweep presentation plotted across days. Control animals extinguish freezing to both CS+ and CS− significantly different. Asterisk refers to a difference between CS+ and CS−. (C) mPFC-NR1 KO mice extinguish CS+ and CS− the same rate. (D) Learning curves comparing slopes of extinction to CS+ and CS− between control (CS+ slope(α) = −9.51 ± 0.72, CS− slope(α) = −9.11 ± 1.10) and mPFC-NR1 KO mice (CS+ slope(α) = −6.07 ± 0.64, CS− slope(α) = −6.34 ± 0.74. (E) Average slope comparison of extinction curves to CS+ and CS− between control and mPFC-NR1 KO mice shows a significant difference in rate of extinction to CS+ and CS−. Shown here (B and C)) fear baseline is % freezing recorded before tone was presented during extinction (days 2–8). The asterisks indicate statistical significance: **, p < 0.01.

2.5. Histology

Histology was performed as described before (Lovelace, Vieira, Corches, Mackie, & Korzus, 2014). Briefly, anesthetized (Nembutal 200 mg/kg, i.p. injection) mice were transcardially perfused first with PBS and then 4% PFA. Brains were extracted, soaked in 4% PFA overnight, soaked in 20% sucrose until they sank, and then flash frozen using embedding media, dry ice, and ethanol before being stored in a −80 °C freezer. The frozen brain was then mounted in a cryostat for 50-μm-thick sectioning of the mPFC. Free-floating immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed on sections according to a previously described protocol (Korzus et al., 2004). The sections are washed 3 times for 10 min in a wash buffer (PBS, 0.3% Triton x-100, 0.02% NaN2) followed by a 1-h incubation in blocking buffer (5% normal goat serum in washing buffer), followed by a 10-min incubation in the wash buffer. The sections were incubated overnight at 4C° with primary antibodies (mouse anti-NeuN monoclonal antibody (Millipore, 1:2000) and rat anti-mCherry (Molecular Probes, 1:10,000) or mouse anti-CaMKII antibody (Fisher, clone: 6G9: 1:1000) and rat anti-mCherry.

After three washes with the wash buffer, the sections were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (Alexa488 goat anti-mouse IgG or Biotin-anti-rat IgG or Alexa647 goat anti-mouse IgG; Molecular Probes, 1:1000), in blocking buffer overnight at 4C°. The sections were washed again three times with the wash buffer, incubated with Streptavidin-Alexa 568 (Molecular Probes, 1:1000) in blocking buffer for 4 h at room temperature, and washed before mounting for viewing. Negative control slices were collected at the same time, undergoing the same IHC procedure in addition to receiving primary antibodies. After immunostaining, the tissue was mounted with mounting medium (ProLong Antifade, LifeTechnologies) before imaging. The negative control slice was from animals infected with HSV/CamKIIα Promoter-mCherry Control virus (Fig. 1A) targeted to mPFC.

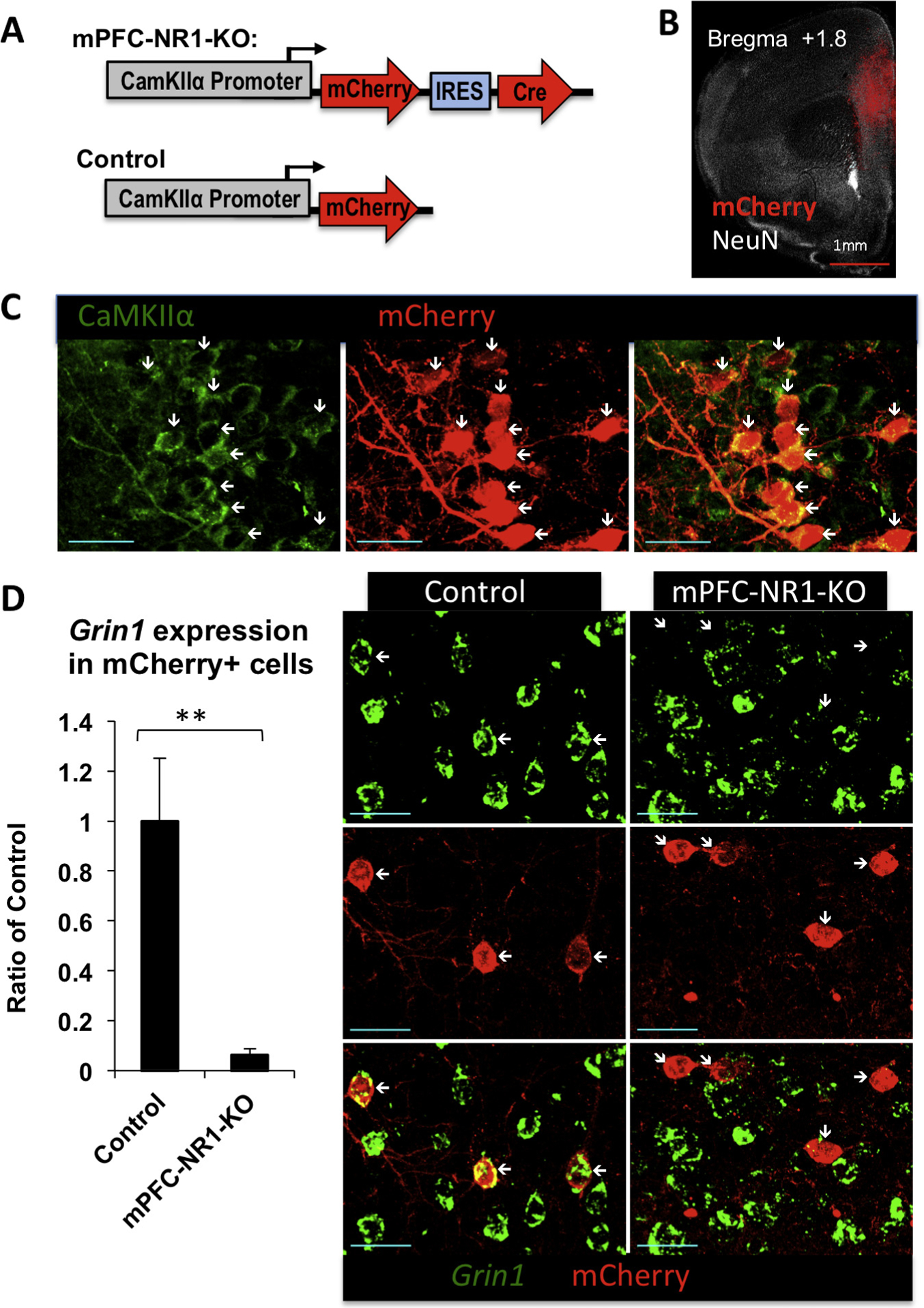

Fig. 1.

Generation of mPFC-NR1 KO mice. (A) Viral construct for generating mPFC-NR1 KO and control mice: HSV/CaMKIIα-mCherry-IRES-Cre and HSV/CaMKIIα-mCherry, respectively. (B) Representative image indicating mPFC infection of the virus. Long-term expression HSV-1 viruses carrying CRE (HSV/CaMKIIα-mCherry-IRES-Cre) or mCherry as the control (HSV/CaMKIIα-mCherry) were injected into the mouse mPFC. To determine the pattern of mCherry-tagged virus expression, the imaged tissue was compared to the Paxinos and Franklin mouse atlas (Paxinos & Franklin, 2001) and areas of maximal mCherry expression were labeled as injection sites. Red, mCherry; white, NeuN neuronal marker. (C) Multiplex immunohistochemistry with anti-mCherry and anti-CamKIIα antibodies revealed that mCherry expression from HSV/CaMKIIα-mCherry-IRES-Cre virus was targeted to CamKIIα positive cells in mPFC-NR1 KO mice. Red, mCherry; green, CaMKIIα. White arrows indicate position of mCherry positive neurons expressing CamKII. Blue scale bar indicates 30 μm. (D) NR1 expression was markedly decreased in mPFC-NR1 KO mice. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was used to measure the levels of NR1 mRNA in combination with immunohistochemistry of mCherry in the mPFC of mPFC-NR1 KO and control mice. Cells co-expressing mCherry in the mPFC showed significantly lower levels of Grin1 expression when compared to control animals expressing mCherry only. Red, mCherry; green, Grin1. White arrows indicate position of mCherry positive neurons. Blue scale bar indicates 30 μm. The asterisks indicate statistical significance: **p < 0.01.

2.6. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) of NR1 mRNA,

Coronal sections (25 mm in thickness) were cut on a Cryostat. Hybridization was performed at 56 °C for 18 h in a hybridization buffer (KPL, Inc). The NR1 probe template derived from the 723-bp DNA fragment of rat NR1 cDNA (pCI-SEP-NRI, Adgene) containing NR1 sequences spanning exon 13 to exon 17 (corresponding to nucleotides 1983 to 2735 based on NCBI Sequence L08228.1). NR1 complementary RNA (cRNA) was labeled with fluorescein (Roche) and used as the probe for detecting NR1 mRNA in the mouse brain. After hybridization, the sections were washed and incubated with HRP conjugated anti-fluorescent antibody (Perkin Elmer) overnight at 4 °C. NR1 signal was detected with the Perkin Elmer kit using fluorescein-tyramide (TSA Plus, Perkin Elmer). Following FISH, mCherry signal was detected with rat anti-Cherry antibodies/Biotin-anti-rat IgG/Streptavidin-Alexa 568 immunodetection system as described above. The negative control slice was from animals infected with HSV/CamKIIα Promoter-mCherry Control virus (Fig. 1A) targeted to mPFC.

2.7. Imaging

Images were taken using an Olympus FV1000 laser scanning confocal microscope controlled using the FluoView software. Fluorescence was measured from mPFC slices using objective 40×/0.80 LUMPlanFL40x objective. Alexa488, Alexa568 and Alexa-647 were imaged using a 473-nm, 559-nm and 647-nm laser, respectively. Gain and offset of each channel were balanced manually using Fluoview saturation tools for maximal contrast. All settings were tested on multiple slices before data collection and brain slices were imaged using identical microscope settings once established. The fluorescence intensity was compared to the negative control slices, which did not receive any primary antibodies. Forty-micrometer z-stacks were obtained from the entire mPFC for assessing the site of injection (Fig. 1B). For other measurements, a single optical section was acquired and analyzed. The fluorescence intensity quantification was performed on original images by the use of Olympus Fluoview software without any non-linear image adjustments. The region of interest (ROI) was a cell-size circle placed on cells expressing mCherry within cortical layer 2/3 in mPFC and fluorescence corresponding to Grin1 (FISH) or CamKII was measured from randomly selected 20–30 cells per hemisphere. The fluorescence intensity quantification was performed on original images by the use of Olympus Fluoview software without post-hock manipulations.

2.8. Data analysis

The experimenters were blind to the group conditions. N indicates sample size and error bars use the standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed using Excel (Microsoft Inc.) or SPSS (IBM Inc.). The Student’s t-test or ANOVA was used for statistical comparisons. Pearson’s correlation (r) was used as an effect size. In cases where the repeated measures ANOVA (RM-ANOVA) was utilized and assumptions of sphericity were violated (via Mauchly’s Test), the analysis was performed using the Green-house-Geisser correction. Bonferroni corrected post hoc analysis was performed for multiple comparisons, which allows for substantially conservative control of the error rate. Significance values were set at p < 0.05. The asterisks indicate statistical significance: *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001 and n.s. indicates not significant.

3. Results

3.1. Generation of mPFC-NR1 KO mice

In this study, we focused on the NMDAR, which is a known regulator of synaptic activity. This receptor has been implicated in forms of synaptic plasticity underlying memory (Bliss & Collingridge, 1993; Tsien, Huerta, & Tonegawa, 1996). Loss of NMDAR function is achieved by the conditional deletion of the Grin1 gene, which encodes an obligatory NR1 subunit for functional NMDAR (Tsien et al., 1996). In most experiments in the current studies, we injected Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) expressing monomeric fluorescent protein mCherry (CamKIIα-mCherry) or mCherry and Cre recombinase under control of CamKIIα promoter (CamKIIα-mCherry/Cre) (Fig. 1A) into the mPFC of floxed-NR1 mice to generate Control or mPFC-NR1 KO mice, respectively (Fig. 1A and B). Cre recombinase is the second gene in our CamKIIα-mCherry/Cre bicistronic vector and linked to mCherry with the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) of encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV). We have previously reported that more then 98% HSV infected cell are neurons (Vieira et al., 2014). Immunostaining with antibodies directed against CamKIIα and mCherry revealed that the virus expression was targeted to CamKIIα positive cells (Fig. 1C). To evaluate NR1 gene deletion in mPFC-NR1 KO, we employed fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to examine expression of NR1 mRNA levels in infected neurons (mCherry expressing cells) (Fig. 1D). mPFC-NR1 KO mice show decreased levels of expression of NR1 mRNA in cells infected with CamKIIα-mCherry/Cre virus within the mPFC (Fig. 1D). We found a significant decrease of NR1 mRNA signal in neurons expressing mCherry protein in the mPFC-NR1 KO when compared to control (Fig. 1D; Ctrl vs. mPFC-NR1 KO: t-test; t(11) = 3.4048, p = 0.0059, r = 0.71632).

3.2. Impairment of fear discrimination in mPFC-NR1 KO mice

We tested mPFC-NR1 KO mice using an auditory discrimination task, which examines the ability of mice to recognize the direction (upward or downward) of frequency modulated (FM)-sweeps (Fig. 2). This fear discrimination task requires learning of a dangerous stimulus (CS+) via classical fear conditioning (pairing with foot shock, US) and then a harmless stimulus (CS−) is associated with the nonoccurrence of the US. This assay begins with 3 days of acquisition (a single CS–US per day) followed by a 24 h fear retrieval test on day 4 and a generalization test on days 4–5. The mice are then run through discrimination training on days 7–12 in which they experience 3 sessions: first, they are tested for freezing to CS+ and CS− in context C (without any reinforcement); second, they are exposed to CS+ paired with US (or CS−); third, they are exposed to CS− (or CS+ paired with US). CS− is never reinforced through the entire procedure. During generalization and discrimination, performance was tested in context C, which is substantially different from the conditioning chamber (Context A).

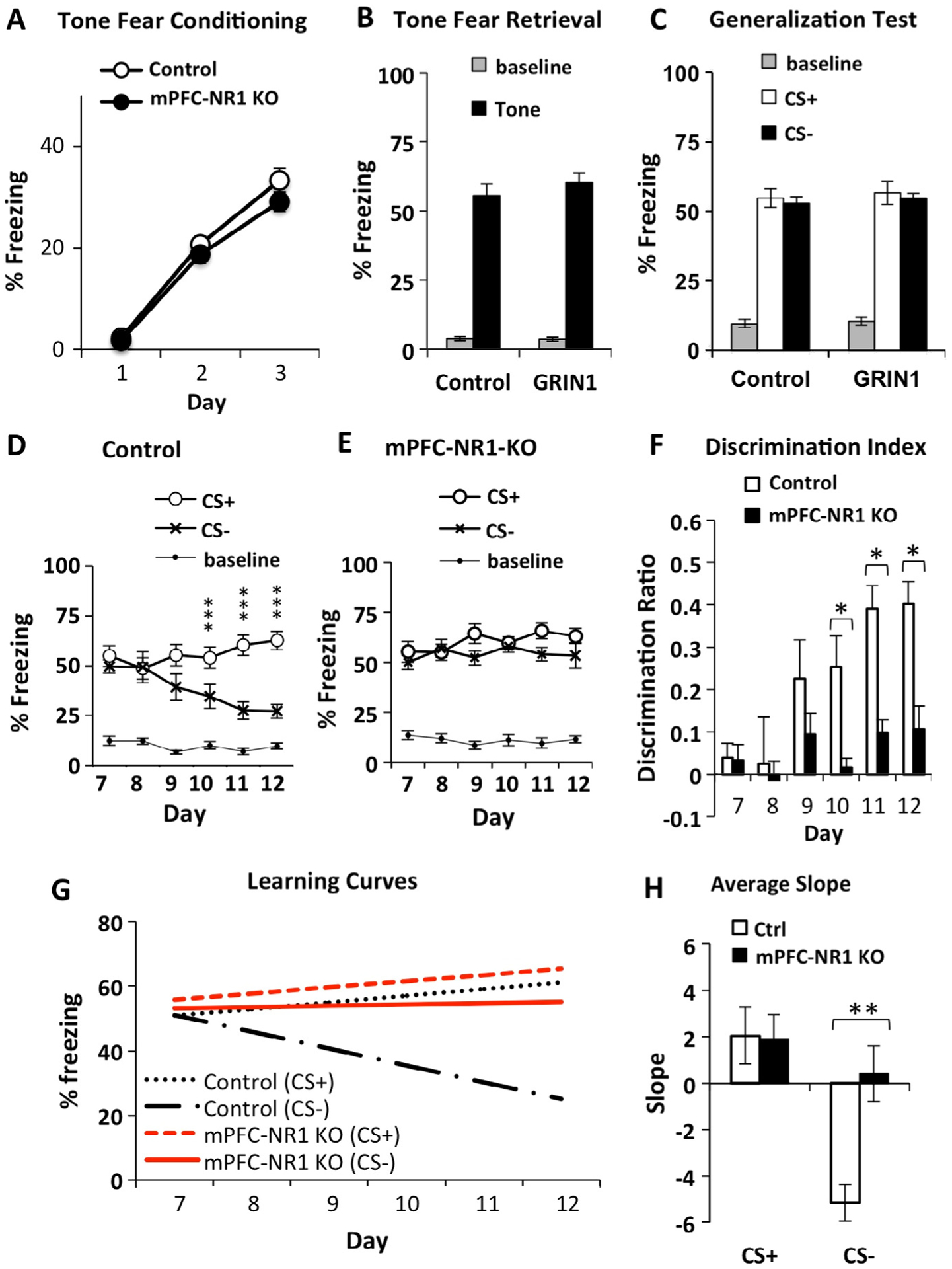

We examined FM-sweep fear conditioning acquisition in mPFC-NR1 KO mice and control mice, and both groups acquired this form of classical conditioning normally (Fig. 3A; RM-ANOVA of Day and Group: F(2,38) = 0.800, p = 0.457). Both groups also showed similar retrieval on a 24-h memory test (Fig. 3B; two way ANOVA of Group and Baseline/24 h-Test; Group: F(1,38) = 0.941, p = 0.338; Baseline/24 h-Test: F(1,38) = 422.288, p = 3.509−22; Group × Baseline/24 h-Test: F(1,38) = 0.553, p = 0.462). We next tested the amount of generalized fear expressed by mPFC-NR1 KO and control mice, in which we examined their freezing responses to a novel FM sweep (CS−), revealing no difference in the freezing responses to the CS− or CS+ between mPFC-NR1 KO and control mice (Fig. 3C; ANOVA of FM-sweep direction and group during day 4 and 5: Group: F(1,38) = 0.363, p = 0.550; ANOVA of FM-sweep direction: F(1,38) = 0.385, p = 0.539; Group × FM-Sweep Direction: F(1,38) = 0.002, p = 0.966). Taken together, these data indicate that both groups of mice show normal conditioned fear acquisition, 24 h retrieval, and generalization.

Fig. 3.

Tone fear discrimination learning is deficient in mPFC-NR1 KO mice. (A and B) Pavlovian tone fear conditioning was normal in mPFC-NR1 KO, showing normal acquisition (A) and retention (B) of FM-sweep fear conditioning compared to control (Ctrl) mice. FM-sweep fear was tested in context C at 24 h after a three upsweeps-foot shock pairing. Shown here fear baseline is% freezing recorded before fear conditioning (day 1). (C) Both groups (mPFC-NR1 KO and Ctrl) show no difference in the freezing responses to CS+ and CS− (p > 0.05) during day 4 and 5 of training, indicating that initially, the mPFC-NR1 KO and control mice generalized responses and did not discriminate between CS+ and CS−. Shown here fear baseline is% freezing recorded before tone was presented during generalization test. (D) After the initial generalization of fear conditioned responses, control mice exhibited robust fear discrimination on Days 10–12. (E) mPFC-NR1 KO mice demonstrated a deficit in auditory fear discrimination when compared to controls (D). Shown here (and F) fear baseline is% freezing recorded before tone was presented during discriminatory phase (days 7–12). (F) The FM-sweep direction discrimination ratios (DI) were calculated using the freezing responses to CS+ and CS− according to the formula DI = (([CS+] − [CS−])/([CS+] + [CS−])). Analyses revealed differences between mPFC-NR1 KO and control mice in the performance during Days 10–12. (G) Average learning curves for learning of appropriate responses to CS+ and CS− were calculated based on the performance of control and mPFC-NR1 KO group across the entire training (Fig. 3D and E; Days 7–12) followed by fitting the regression line and t-test analysis on the mean of those slopes (α). The analysis of patterns of responses to CS+ and CS− in control animals tested on the FM-sweep direction fear discriminatory task revealed that the improvement of auditory fear memory accuracy was due to slight incline in freezing to CS+ and rapid decline in freezing to CS− (CS+/Ctrl: α = 2.05 ± 1.22; CS−/Ctrl: α = −5.17 ± 0.79). There was no difference in the learning (slopes) of appropriate responses to CS+ between mPFC-NR1 KO and control groups. The mPFC-NR1 KO group, which failed to improve fear memory accuracy, showed a positive slope for CS−, a marked difference from control responses to the CS−. (H) Graph showing average slopes on the same analysis. Data presented in B–F were acquired in context C during “Test” (Fig. 2). The asterisks indicate statistical significance: *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, ***, p < 0.001.

We next ran control and mPFC-NR1 KO mice on auditory discrimination training (Fig. 3D–F). Initially, both groups of mice generalized their conditioned responses, exhibiting similar levels of freezing responses to both CS+ and CS− (days 7–8). However, following 2 days of training, control mice demonstrated the ability to consistently distinguish between similar yet different auditory patterns (days 10–12), exhibiting a higher number of freezing responses to CS+ and significantly fewer freezing responses to CS− compared to CS+ (Fig. 3D; RM-ANOVA of Day and FM-sweep direction: Day × FM-sweep direction: F(5,45) = 8.728, p = 0.000007, n = 10). Post hoc analysis using Bonferroni correction (alpha = 0.0083) for multiple comparisons indicated that differences were present during days 10 (t(9) = 3.487, p = 0.007, r = 0.76), 11 (t(9) = 7.209, p = 0.00005, r = 0.92) and 12 (t(9) = 8.147, p = 0.00002, r = 0.94) only.

mPFC-NR1 KO mice demonstrated deficient discrimination between CS+ and CS−, never showing a significant difference in freezing response between up and down auditory sweeps (Fig. 3E, RM-ANOVA of Day and FM-sweep direction: Day × FM-sweep direction: F(2.7,26.5) = 2.787, p = 0.066, n = 11). Post hoc analysis using Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons indicated that no differences were present during days 9 (CS+ vs CS− t-test: t(10) = 2.515, p = 0.031, r = 0.62), 10 (t(10) = 0.655, p = 0.528, r = 0.20), 11 (t(10) = 3.131, p = 0.011, r = 0.70) and 12 (t(10) = 1.728, p = 0.115, r = 0.48). In contrast to the control animals, mPFC-NR1 KO mice continued to generalize their conditioned responses throughout the entire auditory discrimination training and failed to distinguish between CS+ and CS−.

There is a clear deficit in mPFC-NR1 KO mice in auditory fear discrimination when compared to controls (Fig. 3D–E, RM-ANOVA of Group and FM-sweep direction and Day 7–12: Group × FM-sweep direction × Day: F(5,95) = 3.619, p = 0.005; Group × FM-sweep direction: F(1,19) = 5.972, p = 0.024; mPFC-NR1 KO, n = 11; Ctrl, n = 10). Analysis of discrimination ratios supports the difference in performance between control and mPFC-NR1 KO animals on days 10–12 (Fig. 3F. Discrimination Index mPFC-NR1 KO vs. Ctrl t-test: Day 10: t(19) = 3.322, p = 0.004, r = 0.61; Day 11: t(19) = 4.719, p = 0.0001, r = 0.73, Day 12: t(19) = 3.850, p = 0.001, r = 0.66; MPFC-NR1 KO, n = 11; Ctrl, n = 10), but not during the initial 3 days of training (p > 0.05). Control mice clearly show a better performance than mPFC-NR1 KO mice on auditory discrimination (Fig. 3D–F). In sum, these data suggest that knockout of NR1 in the mPFC results in abnormal auditory (FM-sweep direction) fear memory specificity. We have also analyzed the fear baseline measured before tone presentation during testing and we did not find any difference between groups or across the discriminatory training (Fig. 3D–E).

We also analyzed fear responses to upsweep (CS+) and, separately, to downsweep (CS−) in control and mPFC-NR1 KO tested on FM-sweep direction fear discrimination task (Fig. 3). There was no difference in responses to conditioned stimuli CS+ between mPFC-NR1 KO and control mice across the entire FM-sweep direction discrimination training (Fig. 3D–E; CS+/mPFC-NR1 KO vs Ctrl; RM-ANOVA of days 7–12 and group: Day × Group, F(3.1, 59.1) = 0.546, p = 0.659). An analysis of learning curves (Fig. 3G) showed a positive slope to CS+ in control (α = 2.05 ± 1.22) and mPFC-NR1 KO (α = 1.91 ± 1.06) across the entire FM-sweep direction fear discrimination task. In fact, there was no difference in the learning (slopes) of appropriate responses to CS+ between mPFC-NR1 KO and control groups (Fig. 3G; CS+ slope/Ctrl vs mPFC-NR1 KO t-test; t(19) = 0.088, p = 0.931, r = 0.02). However, mPFC-NR1 KO mice responded differently to non-relevant stimuli CS− across training on the auditory discrimination task when compared to control mice (Fig. 3D–E; CS−/mPFC-NR1 KO vs Ctrl; RM-ANOVA of days 1–5 and group: Day × Group, F(3.4,63.7) = 3.447, p = 0.018). The marked improvement of discrimination observed on the FM-sweep direction fear discrimination task in control mice (Fig. 3D, F, G) coincides with the significant negative slope of the learning curve for CS− (Fig. 3G; α = −5.17 ± 0.79). The mPFC-NR1 KO group, which failed to improve fear memory accuracy across training (Fig. 3E–F), shows a slight positive slope for CS− across the training (Fig. 3G; α = 0.412 ± 1.20) and a marked difference when compared to the CS− slope observed in control animals (Fig. 3H; CS− slope/Ctrl vs mPFC-NR1 KO t-test; t(19) = −3.803, p = 0.001, r = 0.66).

In summary, analysis of patterns of responses to CS+ and CS− in control animals tested on the FM-sweep direction fear discrimination task revealed that the improvement of auditory fear memory accuracy was due to only a slight incline in freezing to CS+ and a rapid decline in freezing to CS−. NMDA receptor hypofunction in the mPFC altered the ability to learn auditory discrimination responses to CS+ versus CS− by disrupting the pattern of learning for CS− only, while responses to CS+ remained similar to control mice. These data demonstrate that the mPFC supports the improvement of auditory fear memory accuracy by controlling acquisition of appropriate responses to non-relevant stimuli.

3.3. Impairment of auditory fear memory extinction in mPFC-NR1 KO mice

Previous work on fear memory and mPFC NMDA receptor function demonstrated that infusion of CPP, a potent NMDA receptor antagonist (Burgos-Robles et al., 2007; Santini et al., 2001), or more selective NR2B-specific blocker ifenprodil (Sotres-Bayon et al., 2009) impaired extinction memory consolidation. However, pharmacological manipulation prevents testing cell-type specific effects. To evaluate the specific role of NMDARs expressed in excitatory neurons we tested mPFC-NR1 KO mice on an auditory extinction task (Fig. 4A) in which mice are initially trained with 3 pairings of upward FM sweeps (CS+) and foot shocks on day 1, followed by 7 days of extinction in which they are presented with non-reinforced upward (CS+) and downward (CS−) FM auditory sweeps in a novel context while measuring freezing responses. No further pairing of CS+ and foot shocks was done after the initial training on day 1. Control mice extinguish freezing to CS+ and CS− differently across extinction training (Fig. 4B, RM-ANOVA of Day and FM-sweep direction: Day × FM-sweep direction = F(6,60) = 2.565, p = 0.028). Post hoc analysis indicated that differences between CS+ and CS− were present during days 4 (p < 0.05), and 7 (p < 0.05), only. mPFC-NR1 KO mice show no difference between CS+ and CS− in decline of freezing responses across fear extinction training (Fig. 4C RM-ANOVA of Day and FM-sweep direction: Day × FM-sweep direction = F(6,66) = 2.225, p = 0.051).

Analysis of learning curves (Fig. 4D, Control CS+ α = −9.51 ± 0.72, mPFC-NR1 KO CS+ α = −6.07 ± 0.64, Control CS− α = −9.11 ± 1.10, mPFC-NR1 KO CS− α = −6.34 ± 0.74) shows a significant difference in the rate of extinction of CS+ and CS− between control and mPFC-NR1 KO mice when comparing average slopes of both CS+ (Fig. 4E, CS+ slope/Ctrl vs mPFC-NR1 KO t-test; t(21) = −3.573, p = 0.002, r = 0.61) and CS− (CS− slope/Ctrl vs mPFC-NR1 KO t-test; t(21) = −2.113, p = 0.047, r = 0.52). Taken together, these data indicate that both control and mPFC-NR1 KO groups extinguish CS+ and CS− across extinction training, but that control mice extinguish fear responses to both FM-sweep directions more rapidly than mPFC-NR1 KO mice. While freezing responses to conditioned stimulus CS+ and nonreinforced stimulus CS− declined to the level of fear baseline on day 7 of extinction learning in control group (Fig. 4B; Day 7, CS+ vs baseline (CTRL) t-test(10) = 1.7465, n = 11, p = 0.1113, r = 0.3637; CS− vs Baseline (CTRL) t-test(10) = 0.0277, n = 11, p = 0.9785, r = 0.01), mPFC-NR1 KO mice show still significant levels of freezing to CS+ and CS− above the baseline on day 7 of extinction training (Fig. 4 C; Day 7, CS+ vs baseline (mPFC-NR1 KO) t-test(11) = 7.5947, n = 12, p = 0.00001, r = 0.85; CS− vs baseline (mPFC-NR1 KO) t-test(11) = 3.911, n = 12, p = 0.000002, r = 0.64). Coincidently, generalized fear responses to CS−, which was never reinforced, show similar patterns of decline to those observed in case of CS+ in mPFC-NR1 KO and control mice across the training of fear extinction paradigm (Fig. 4). In general, the decrease of generalized fear (responses to CS−) correlates well with the decrease of fear responses to CS+ across fear extinction training, although control mice show a slightly steeper decline of CS− when compared to CS+ (Fig. 4) while both CS+ and CS− decline slower but at the same rate in mPFC-NR1 KO mice. In summary, these data demonstrate that NMDARs expressed in excitatory neurons in the mPFC not only mediate mechanism underlying fear extinction (Fig. 4) but also are involved in likely separate mechanism controlling a decline of generalized responses to CS− (observed in Fig. 3).

4. Discussion

This study shows that after fear generalization occurs, successful fear discrimination involves prefrontal NMDAR-dependent decline of generalized fear responses to harmless nonreinforced stimuli. Conditional deletion of the NMDAR in CamKIIα positive excitatory neurons within the mPFC resulted in abnormal fear discrimination. Patterns of fear responses in control animals suggest that the fear discrimination procedure involves a diminution of freezing responses to harmless nonreinforced stimuli after initial strong generalization. In addition, mPFC-NR1 KO mice show a moderate deficiency in fear extinction, which is consistent with prior studies demonstrating that infusion of NMDAR antagonist CPP or more selective NR2B specific antagonist ifenprodil into the mPFC prevented consolidation of extinction learning (Burgos-Robles et al., 2007; Santini et al., 2001; Sotres-Bayon et al., 2009).

How can NMDARs in the mPFC control fear discrimination? This study shows that fear discrimination involves a prefrontal mechanism that is mediated by NMDARs expressed in excitatory CamKIIα positive neurons. These studies are consistent with our previous report showing that an interruption of cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) function or an inhibition of histone acetyltransferase CREB binding protein (CBP) activity in the mPFC also leads to a strong deficit in fear discrimination (Vieira et al., 2014). Both CREB and CBP histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity has been implicated in the putative molecular mechanism underlying memory consolidation and NMDAR-dependent synaptic plasticity. Thus, fear discrimination appears to rely on prefrontal circuitry through a process by which initially generalized fear memories are sharpened by selective reduction of the response to non-reinforced stimuli. These studies are consistent with other reports. Critical involvement of mPFC in fear generalization has been demonstrated through prefrontal lesion studies (Zelikowsky et al., 2013) and direct inactivation of connectivity between mPFC and nucleus reuniens of thalamus (NR), which in both studies enhanced fear responses to a novel environment (Xu & Sudhof, 2013). In fact, optogenetic activation of action-potential firing of NR neurons stimulated throughout the 6 min training period by either a 4 Hz tonic stimulation or a 30 Hz phasic stimulation administered for 0.5 s every 5 s during fear memory acquisition (but not during fear memory retrieval) reduced or enhanced memory generalization, respectively (Xu & Sudhof, 2013). Other studies showed that a general inactivation of the mPFC with the GABAA receptor antagonist muscimol did not interfere with differential fear learning but it produced deficit in the differential fear conditioning if muscimol was administered into the mPFC just before retrieval but not during aquisition (Lee & Choi, 2012). These data may indicate that the differential fear learning may occur in absence of the mPFC due to compensatory effects in a similar manner as the prefrontal microcircuit can compensate contextual learning after hippocampal loss (Zelikowsky et al., 2013). However, when required information related to differential fear acquisition is encoded and consolidated in available mPFC network in a NMDAR-dependent manner, then the mPFC becomes indispensable for differential fear retrieval. In summary, these data suggest that fear discrimination recruits a mechanism relying on NMDARs expressed in prefrontal excitatory neurons and controlling a generalization decrement.

mPFC-NR1 KO mice also showed a moderate deficit in extinction of fear to the conditioned stimuli CS+ (Fig. 4), which is consistent with previous reports. It is generally believed that fear behavior is differentially regulated by the PL and IL divisions of the mPFC (Courtin et al., 2013; Quirk & Mueller, 2008; Sierra-Mercado et al., 2010; Sotres-Bayon et al., 2006). Electro-physiological findings suggest that the IL and PL cortices may have opposite effects on fear expression (Gilmartin & McEchron, 2005; Vidal-Gonzalez, Vidal-Gonzalez, Rauch, & Quirk, 2006). It has been suggested that the PL promotes fear expression by activating neurons of the basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (BLA) projecting to the central nucleus of the amygdala (CeM) (Pape & Pare, 2010), a critical subregion for fear expression. Conversely, electrical stimulation of IL inhibits the CeM output through the amygdala intercalated neurons (ITC) relay (Royer, Martina, & Pare, 1999), providing an alternative mechanism for extinction (Likhtik, Popa, Apergis-Schoute, Fidacaro, & Pare, 2008). Thus, IL mPFC projections to the amygdala inhibit conditioned fear and it is postulated that the learning of fear extinction in rats involves both increased neuronal activity in the IL mPFC (Milad & Quirk, 2002) and protein synthesis in the mPFC (Santini, Ge, Ren, Pena de Ortiz, & Quirk, 2004).

NMDARs have been strongly implicated in fear extinction. NMDAR-dependent long-term potentiation is an experimental model of synaptic plasticity and is widely hypothesized to be the neural mechanism by which memory traces are encoded and stored in the brain (Martin, Grimwood, & Morris, 2000). Infusion of the NMDAR blocker 2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate (APV) into in the amygdala during extinction substantially interferes with extinction of conditioned fear to tone, light, and contextual stimuli (Falls, Miserendino, & Davis, 1992; Lee & Kim, 1998) while overexpression of NMDAR subunit NR2B in mice improves extinction learning (Tang et al., 1999). In addition, pre-training injections of antagonist of NMDA-type receptors 3-(2-carboxypiperazin-4-yl)-propyl-1-phosphonic acid (CPP) directly to the mPFC demonstrated that NMDA receptors are not required fear extinction training while immediate post-training (but not 2 h after) injections of CCP impaired subsequent retrieval of extinction implicating NMDAR in long-term memory (Burgos-Robles et al., 2007; Santini et al., 2001). In addition, consolidation of fear extinction requires NMDAR-dependent bursting in the mPFC (Burgos-Robles et al., 2007) suggesting that fear extinction learning involves extinction memory through NMDAR-mediated plasticity in prefrontal-amygdala circuits. Furthermore, NR2B subunit of prefrontal NMDARs, which has been implicated in induction of synaptic plasticity (Barria & Malinow, 2005; Sobczyk, Scheuss, & Svoboda, 2005) appears to be critical for fear extinction consolidation but is dispensable during fear extinction training (Sotres-Bayon et al., 2009).

While decline of fear response to CS+ due to fear memory extinction (Fig. 4) and reduction of responses to CS− due to a generalization decline (Fig. 3) show similar behavioral patterns, circuit level mechanisms are likely different. Reduction of responses to conditioned stimulus CS+ is linked to well-studied mechanism underlying fear memory extinction (described above) and decline of fear responses to non-reinforced CS− is connected to a generalization decrement. mPFC-NR1 KO mice show deficit in both of these mechanisms suggesting that they may share similar requirements for prefrontal excitatory neurons expressing NMDARs. However, it is unclear if the same excitatory neurons in the mPFC govern both fear memory extinction and a generalization decrement or separate prefrontal circuits control these two mechanisms. The fact that behavioral effects of NMDARs deletion from prefrontal excitatory neurons is less severe in case of fear memory extinction (Fig. 4) when compared to fear discrimination (Fig. 3) may indicate that fear extinction learning and a generalization decline are governed through separate neuronal populations and varying involvement PL and/or IL.

Additional supporting evidence for the mPFC as a locus for gating fear discrimination includes animal studies in which a mPFC lesion impairs the ability to guide behavior, specifically when memory retrieval resolves conflicting dangerous and harmless contextual cues (Birrell & Brown, 2000; Dias, Robbins, & Roberts, 1996; Ragozzino, Kim, Hassert, Minniti, & Kiang, 2003; Rich & Shapiro, 2007). A fear decline is associated with elevated activity in the mPFC as determined by activation of immediate-early genes (Herry & Mons, 2004; Knapska & Maren, 2009), increased blood oxygenation levels (Phelps, Delgado, Nearing, & LeDoux, 2004), cell firing (Burgos-Robles et al., 2007) and magnitude of local field potentials (Lesting et al., 2011). The mPFC has dense reciprocal anatomical and functional connections with sensory cortices, thalamic sensory relays and memory systems including the hippocampus and basolateral amygdala (BLA), the critical locus for fear processing. In addition, considerable evidence indicates that neurons in the mPFC, BLA and hippocampus are functionally coupled at the theta range (4–12 Hz oscillations) during fear conditioning (Popa, Duvarci, Popescu, Lena, & Pare, 2010; Seidenbecher, Laxmi, Stork, & Pape, 2003), conditioned extinction (Lesting et al., 2011) and discriminative fear learning (Likhtik, Stujenske, Topiwala, Harris, & Gordon, 2014). These studies also have clinical implications. Over-generalized fear is a typical symptom of anxiety disorders including generalized anxiety disorder (Gazendam, Kamphuis, & Kindt, 2013; Reinecke, Becker, Hoyer, & Rinck, 2010) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Jovanovic, Kazama, Bachevalier, & Davis, 2012), which are triggered by cues in a secure environment that resemble those of the traumatic experience. Failure to discriminate between dangerous and harmless stimuli can lead to intrusive recollection of aversive memories. Our studies reveal that NMDARs expressed in prefrontal excitatory neurons control the ability to distinguish between dangerous and harmless stimuli.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms previous evidence demonstrating the involvement of mPFC in fear discrimination. In addition, current work shows that prefrontal NMDAR-dependent signaling in the CamKIIα positive excitatory cells is critical for disambiguating the meaning of fear signals. Our previous study also implicated CREB and CBP HAT activity in the mPFC in fear discrimination learning (Vieira et al., 2014). Considering that three components (NMDAR/CREB/CBP) of the molecular mechanism underlying long-term plasticity in the mPFC are directly implicated in appropriate disambiguation of fear signals, we suggest that fear discrimination involves long-term memory coding into the prefrontal excitatory circuitry. Further experiments are needed to reveal what type of information is consolidated in the mPFC that is required for a reduction of generalized fear to harmless stimuli required for the improvement of fear memory accuracy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH/NIMH grant MH086078 (to E.K.) and UCR Collaborative Research Seed Grant (to E.K.) and the Ford Fellowship (to P.A.V.). We thank N. Bavadian and A. Hiroto for their technical assistance in behavioral studies. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Abbreviations:

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- BLA

basolateral amygdala

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- IL

infralimbic cortex

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors

- PL

prelimbic cortex

- RM-ANOVA

repeated measures-ANOVA

References

- Barria A, & Malinow R (2005). NMDA receptor subunit composition controls synaptic plasticity by regulating binding to CaMKII. Neuron, 48, 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell JM, & Brown VJ (2000). Medial frontal cortex mediates perceptual attentional set shifting in the rat. Journal of Neuroscience, 20, 4320–4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, & Collingridge GL (1993). A synaptic model of memory: Long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature, 361, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouton ME, & Nelson JB (1994). Context-specificity of target versus feature inhibition in a feature-negative discrimination. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 20, 51–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breier A, Su TP, Saunders R, Carson RE, Kolachana BS, de Bartolomeis A, et al. (1997). Schizophrenia is associated with elevated amphetamine-induced synaptic dopamine concentrations: Evidence from a novel positron emission tomography method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 94, 2569–2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos-Robles A, Vidal-Gonzalez I, Santini E, & Quirk GJ (2007). Consolidation of fear extinction requires NMDA receptor-dependent bursting in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Neuron, 53, 871–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins DR, & Pare D (2000). Differential fear conditioning induces reciprocal changes in the sensory responses of lateral amygdala neurons to the CS(+) and CS(−). Learning and Memory, 7, 97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtin J, Bienvenu TC, Einarsson EO, & Herry C (2013). Medial prefrontal cortex neuronal circuits in fear behavior. Neuroscience, 240, 219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVito LM, Lykken C, Kanter BR, & Eichenbaum H (2010). Prefrontal cortex: Role in acquisition of overlapping associations and transitive inference. Learning and Memory, 17, 161–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, Robbins TW, & Roberts AC (1996). Dissociation in prefrontal cortex of affective and attentional shifts. Nature, 380, 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falls WA, Miserendino MJ, & Davis M (1992). Extinction of fear-potentiated startle: Blockade by infusion of an NMDA antagonist into the amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience, 12, 854–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland PW, & Bontempi B (2005). The organization of recent and remote memories. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6, 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankland PW, Bontempi B, Talton LE, Kaczmarek L, & Silva AJ (2004). The involvement of the anterior cingulate cortex in remote contextual fear memory. Science, 304, 881–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbott PL, Warner TA, Jays PR, Salway P, & Busby SJ (2005). Prefrontal cortex in the rat: Projections to subcortical autonomic, motor, and limbic centers. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 492, 145–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazendam FJ, Kamphuis JH, & Kindt M (2013). Deficient safety learning characterizes high trait anxious individuals. Biological Psychology, 92, 342–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz JC, Falls WA, & Davis M (1997). Normal conditioned inhibition and extinction of freezing and fear-potentiated startle following electrolytic lesions of medical prefrontal cortex in rats. Behavioral Neuroscience, 111, 712–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin MR, & McEchron MD (2005). Single neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat exhibit tonic and phasic coding during trace fear conditioning. Behavioral Neuroscience, 119, 1496–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herry C, & Mons N (2004). Resistance to extinction is associated with impaired immediate early gene induction in medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala. European Journal of Neuroscience, 20, 781–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JC, & Crepel F (1991). Blockade of NMDA receptors unmasks a long-term depression in synaptic efficacy in rat prefrontal neurons in vitro. Experimental Brain Research, 85, 621–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homayoun H, & Moghaddam B (2007). NMDA receptor hypofunction produces opposite effects on prefrontal cortex interneurons and pyramidal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience, 27, 11496–11500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson ME, Homayoun H, & Moghaddam B (2004). NMDA receptor hypofunction produces concomitant firing rate potentiation and burst activity reduction in the prefrontal cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101, 8467–8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs NS, Cushman JD, & Fanselow MS (2010). The accurate measurement of fear memory in Pavlovian conditioning: Resolving the baseline issue. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 190, 235–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic T, Kazama A, Bachevalier J, & Davis M (2012). Impaired safety signal learning may be a biomarker of PTSD. Neuropharmacology, 62, 695–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, & Fanselow MS (1992). Modality-specific retrograde amnesia of fear. Science, 256, 675–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapska E, & Maren S (2009). Reciprocal patterns of c-Fos expression in the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala after extinction and renewal of conditioned fear. Learning and Memory, 16, 486–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzus E, Rosenfeld MG, & Mayford M (2004). CBP histone acetyltransferase activity is a critical component of memory consolidation. Neuron, 42, 961–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti AC, Holcomb HH, Medoff DR, & Tamminga CA (1995). Ketamine activates psychosis and alters limbic blood flow in schizophrenia. NeuroReport, 6, 869–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YK, & Choi JS (2012). Inactivation of the medial prefrontal cortex interferes with the expression but not the acquisition of differential fear conditioning in rats. Experimental Neurobiology, 21, 23–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, & Kim JJ (1998). Amygdalar NMDA receptors are critical for new fear learning in previously fear-conditioned rats. Journal of Neuroscience, 18, 8444–8454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesting J, Narayanan RT, Kluge C, Sangha S, Seidenbecher T, & Pape HC (2011). Patterns of coupled theta activity in amygdala–hippocampal–prefrontal cortical circuits during fear extinction. PLoS ONE, 6, e21714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtik E, Popa D, Apergis-Schoute J, Fidacaro GA, & Pare D (2008). Amygdala intercalated neurons are required for expression of fear extinction. Nature, 454, 642–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhtik E, Stujenske JM, Topiwala MA, Harris AZ, & Gordon JA (2014). Prefrontal entrainment of amygdala activity signals safety in learned fear and innate anxiety. Nature Neuroscience, 17, 106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim F, & Neve RL (2001). Generation of high-titer defective HSV-1 vectors. Current Protocols in Neuroscience [Chapter 4, Unit 4 13]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovelace JW, Vieira PA, Corches A, Mackie K, & Korzus E (2014). Impaired fear memory specificity associated with deficient endocannabinoid-dependent long-term plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology, 39, 1685–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, & Fanselow MS (1995). Synaptic plasticity in the basolateral amygdala induced by hippocampal formation stimulation in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience, 15, 7548–7564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maren S, & Quirk GJ (2004). Neuronal signalling of fear memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5, 844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SJ, Grimwood PD, & Morris RG (2000). Synaptic plasticity and memory: An evaluation of the hypothesis. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 23, 649–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina JF, Repa JC, Mauk MD, & LeDoux JE (2002). Parallels between cerebellum- and amygdala-dependent conditioning. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3, 122–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milad MR, & Quirk GJ (2002). Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature, 420, 70–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MA, Romanski LM, & LeDoux JE (1993). Extinction of emotional learning: Contribution of medial prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience Letters, 163, 109–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve RL, & Lim F (2001). Overview of gene delivery into cells using HSV-1-based vectors. Current Protocols in Neuroscience [Chapter 4, Unit 4 12]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini CA, Kim JH, Knapska E, & Maren S (2011). Hippocampal and prefrontal projections to the basal amygdala mediate contextual regulation of fear after extinction. Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 17269–17277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsini CA, & Maren S (2012). Neural and cellular mechanisms of fear and extinction memory formation. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pape HC, & Pare D (2010). Plastic synaptic networks of the amygdala for the acquisition, expression, and extinction of conditioned fear. Physiological Reviews, 90, 419–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, & Franklin KBJ (2001). The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phelps EA, Delgado MR, Nearing KI, & LeDoux JE (2004). Extinction learning in humans: Role of the amygdala and vmPFC. Neuron, 43, 897–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa D, Duvarci S, Popescu AT, Lena C, & Pare D (2010). Coherent amygdalocortical theta promotes fear memory consolidation during paradoxical sleep. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107, 6516–6519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JJ, Ma QD, Tinsley MR, Koch C, & Fanselow MS (2008). Inverse temporal contributions of the dorsal hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex to the expression of long-term fear memories. Learning and Memory, 15, 368–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, & Mueller D (2008). Neural mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 56–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk GJ, Russo GK, Barron JL, & Lebron K (2000). The role of ventromedial prefrontal cortex in the recovery of extinguished fear. Journal of Neuroscience, 20, 6225–6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragozzino ME, Kim J, Hassert D, Minniti N, & Kiang C (2003). The contribution of the rat prelimbic-infralimbic areas to different forms of task switching. Behavioral Neuroscience, 117, 1054–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke A, Becker ES, Hoyer J, & Rinck M (2010). Generalized implicit fear associations in generalized anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 27, 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich EL, & Shapiro ML (2007). Prelimbic/infralimbic inactivation impairs memory for multiple task switches, but not flexible selection of familiar tasks. Journal of Neuroscience, 27, 4747–4755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer S, Martina M, & Pare D (1999). An inhibitory interface gates impulse traffic between the input and output stations of the amygdala. Journal of Neuroscience, 19, 10575–10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini E, Ge H, Ren K, Pena de Ortiz S, & Quirk GJ (2004). Consolidation of fear extinction requires protein synthesis in the medial prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 24, 5704–5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santini E, Muller RU, & Quirk GJ (2001). Consolidation of extinction learning involves transfer from NMDA-independent to NMDA-dependent memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 21, 9009–9017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenbecher T, Laxmi TR, Stork O, & Pape HC (2003). Amygdalar and hippocampal theta rhythm synchronization during fear memory retrieval. Science, 301, 846–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Mercado D, Padilla-Coreano N, & Quirk GJ (2010). Dissociable roles of prelimbic and infralimbic cortices, ventral hippocampus, and basolateral amygdala in the expression and extinction of conditioned fear. Neuropsychopharmacology, 36, 529–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobczyk A, Scheuss V, & Svoboda K (2005). NMDA receptor subunit-dependent [Ca2+] signaling in individual hippocampal dendritic spines. Journal of Neuroscience, 25, 6037–6046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotres-Bayon F, Cain CK, & LeDoux JE (2006). Brain mechanisms of fear extinction: Historical perspectives on the contribution of prefrontal cortex. Biological Psychiatry, 60, 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotres-Bayon F, Diaz-Mataix L, Bush DE, & LeDoux JE (2009). Dissociable roles for the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and amygdala in fear extinction: NR2B contribution. Cerebral Cortex, 19, 474–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotres-Bayon F, & Quirk GJ (2010). Prefrontal control of fear: More than just extinction. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 20, 231–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR (1992). Memory and the hippocampus: A synthesis from findings with rats, monkeys, and humans. Psychological Review, 99, 195–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Jodo E, Takeuchi S, Niwa S, & Kayama Y (2002). Acute administration of phencyclidine induces tonic activation of medial prefrontal cortex neurons in freely moving rats. Neuroscience, 114, 769–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YP, Shimizu E, Dube GR, Rampon C, Kerchner GA, Zhuo M, et al. (1999). Genetic enhancement of learning and memory in mice. Nature, 401, 63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tse D, Takeuchi T, Kakeyama M, Kajii Y, Okuno H, Tohyama C, et al. (2011). Schema-dependent gene activation and memory encoding in neocortex. Science, 333, 891–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien JZ, Huerta PT, & Tonegawa S (1996). The essential role of hippocampal CA1 NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in spatial memory. Cell, 87, 1327–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP (2004). Differential projections of the infralimbic and prelimbic cortex in the rat. Synapse (New York, N. Y.), 51, 32–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Gonzalez I, Vidal-Gonzalez B, Rauch SL, & Quirk GJ (2006). Microstimulation reveals opposing influences of prelimbic and infralimbic cortex on the expression of conditioned fear. Learning and Memory, 13, 728–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira PA, Lovelace JW, Corches A, Rashid AJ, Josselyn SA, & Korzus E (2014). Prefrontal consolidation supports the attainment of fear memory accuracy. Learning and Memory, 21, 394–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollenweider FX, Leenders KL, Oye I, Hell D, & Angst J (1997). Differential psychopathology and patterns of cerebral glucose utilisation produced by (S)- and (R)-ketamine in healthy volunteers using positron emission tomography (PET). European Neuropsychopharmacology, 7, 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Morishita W, Buckmaster PS, Pang ZP, Malenka RC, & Sudhof TC (2012). Distinct neuronal coding schemes in memory revealed by selective erasure of fast synchronous synaptic transmission. Neuron, 73, 990–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, & Sudhof TC (2013). A neural circuit for memory specificity and generalization. Science, 339, 1290–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelikowsky M, Bissiere S, Hast TA, Bennett RZ, Abdipranoto A, Vissel B, et al. (2013). Prefrontal microcircuit underlies contextual learning after hippocampal loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110, 9938–9943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]