Abstract

In this paper, COVID-19 dynamics are modelled with three mathematical dynamic models, fractional order modified SEIRF model, stochastic modified SEIRF model, and fractional stochastic modified SEIRF model, to characterize and predict virus behavior. By using Euler method and Euler-Murayama method, the numerical solutions for the considered models are obtained. The considered models are applied to the case study of Egypt to forecast COVID-19 behavior for the second virus wave which is assumed to be started on 15 November 2020. Finally, comparisons between actual and predicted daily infections are presented.

Keywords: COVID-19, Fractional dynamic models, Stochastic dynamic models, Euler-Murayama method

Introduction

Mathematical modeling approach is a strong key tool in order to handle different infectious diseases [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. Many real-world problems in science and engineering can be modeled by stochastic differential equations [10], [11], [12]. Fractional differential equations have been widely applied in many fields such as physics, chemical, fluid dynamic and epidemic models [13], [14]. The main challenge according studying infectious diseases is the way to predict the disease behavior and how many people will be infected in the future. Different researchers from different interdisciplinary such as applied mathematics and data science have been working on studying these types of predictions so it becomes a great area of research. Such studies are now focusing on describing COVID-19 dynamics as it became an epidemic disease. Dynamic models are used to model viral waves and time of actions to calculate the total number of infections and deaths. In all studies, COVID-19 transmission rates are varied from one country to another and similarly the virus dynamics as it depends on the behaviors of individuals, temperature, relative air humidity and wind speed. Based on these predictions and studies, governments can take more suitable actions to mitigate human and economic losses.

On the other hand, the classic susceptible exposed infectious recovered model (SEIR) is adopted model for characterizing the epidemic of COVID-19 outbreak in different countries. The extension of classical SEIR model with delays is another routine to simulate the incubation period and the period before recovery [15]. In [16], authors used numerical approaches and logistic modelling technique to make complete analysis for COVID-19. In [17], authors made a fractional order modified SEIR model of pandemic diseases and apply it on COVID-19 to predict virus spreading behavior in Pakistan and Malaysia. In [18], authors made predictions about Coronavirus transmission dynamics in the African countries. The model parameters (protection rate, infection rate, average incubation time, average quarantined time, cure rate, and mortality rate) are selected using Metropolis-Hasting (MH) parameter optimization method [19]. Further study for modelling COVID-19 daily confirmed cases in Egypt and Iraq by using Gaussian fitting model and logistic model is reached [20], [21], [22]. The virus dynamic behavior is modelled with a new SEIR model. One of the important quantities should be calculated during modelling virus dynamics is the basic reproduction number. This value helps to eliminate the diseases and expect number of secondary infections produced by an infected individual when all individuals are susceptible to infections. In [23], authors made a multi-strain modified SEIR epidemic model for COVID-19 and wrote a complete analysis on how to control the value of the reproduction number for next upcoming virus peaks.

Based on the above-mentioned works, by using Euler method and Euler-Murayama method, we study the predictions of COVID-19 second wave in Egypt through developing different dynamic mathematical models. In particular, the fractional order dynamic model, stochastic dynamic model and the fractional order stochastic dynamic model. Finally, comparisons between actual and predicted daily infections are presented. Secondary data for Egypt first viral wave are carefully collected from references [24], [25]. The second virus wave of Egypt is assumed started on 15 November 2020.

This paper is prepared as follows. In Section “Preliminaries”, we review some essential facts from fractional calculus and stochastic analysis. In Section “COVID-19 dynamical models”, we describe COVID-19 dynamical models. In Section “Results and discussion”, we apply dynamical models on case study of Egypt and compare between actual and predicted daily infections. In the end, conclusions and future work are written.

Preliminaries

Definition 2.1

Riemann-Liouville fractional integral operator of orderfor a functioncan be defined as[26]:

Definition 2.2

Caputo derivative of orderwith the lower limit zero for a functioncan be written as[27]:

Definition 2.3

A standard one-dimensional Wiener process is a stochastic processindexed by nonnegative real numbers t with the following properties[28], [29], [30]:

-

(1)

with probability 1.

-

(2)

The function is continuous on t.

-

(3)

If then and are independent.

-

(4)

For ∀, all increments , are normally distributed with mean 0 and variance i.e., .

Definition 2.4

First order n-dimensional stochastic differential equation (SDE) indexed by nonnegative real numbers t is defined as [28]:

where is time; is the state vector; is a vector of parameter values; and the functions { and { are the drift and diffusion terms respectively of the SDE and represents the stochastic Wiener process.

Euler-Maruyama method

One of the simplest numerical approximations for the SDE is the Euler-Maruyama method. If we truncate Ito’s formula of the stochastic Taylor series after the first order terms, we obtain the Euler-Maruyama method as follows:

with the initial value .

COVID-19 dynamical models

Based on the epidemiological feature of COVID-19 and the several strategies imposed by the government, with different degrees, to fight against this pandemic, we extend the classical SEIR model [23] to describe the transmission of COVID-19. In particular, we partitioned the population into five classes, denoted by S, E, I, R and F, where S represents the daily Susceptible individuals; E is the daily Exposed individuals; I the daily Infected individuals, which have not yet been treated. Finally, R and I are the daily Recovered and daily Deaths. All proposed model satisfy the following assumptions:

-

(1)

All involved transmission rates, for such models, are positive and varying with time.

-

(2)

Natural birth and death rate are not considered.

-

(3)

Symptomatic patients are only who transmit the virus.

-

(4)

Susceptible individuals can move into infected class without passing by exposed class.

-

(5)

Second infection of individuals is not considered in the model.

COVID-19 dynamics are modelled with three mathematical dynamic models which are:

-

•

Fractional order modified SEIRF model.

-

•

First order stochastic modified SEIRF model.

-

•

Fractional order stochastic modified SEIRF model.

Fractional order modified SEIRF model

Caputo fractional derivative [31] of order , , is applied on our SEIRF modelling Eqs. (1), (2), (3), (4), (5). Through varying the value of , different viral wave peaks can be reached to describe virus dynamics with more than one scenario. Taking equals 1 results in generating first order modified SEIRF so it is a special case of the fractional order modified SEIRF model. Through modelling Eqs. (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), Daily Susceptible (S) enter the Exposed class (E) due to contact between exposed individuals and infected individuals. Susceptibles move to Exposed class with daily transmission rate and into infected class with daily transmission rate . Exposed (E) enter the Infected class (I) with daily transmission rate . A part of infected individuals moves to Recovered class (R) with daily cure rate and the remaining part moves to Deaths class (F) with daily death rate . All rates are assumed dynamic rates and varying with time.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where is the average number of closed contacts between susceptible individuals per infected individuals per day and is the average number of closed contacts between susceptible individuals per exposed individuals per day. The assumed model dynamic rates are defined as:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

where is the incubation period and is a controlling parameter decreasing from country to another according to how precautionary measures are followed. and are the initial values of dynamic system rates.

First order stochastic modified SEIRF model

In this model, COVID-19 dynamic behavior is modelled using equations of the first order modified SERIF model, equals 1, after adding white noise terms satisfying Wiener process properties to all modelling equations. These additions can make modelling equations more realistic in describing COVID-19 viral waves. The new added diffusion terms are as indicated in Eqs. (11), (12), (13), (14), (15). All virus dynamic rates are taking the same form as in the first order modified SEIRF model.

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

where are respectively the diffusion coefficients for Susceptible, Exposed, Infected, Recovered and Deaths individuals.

Fractional order stochastic modified SEIRF model

This dynamic modelling approach authorize an additional novelty and dimension of the article. Modelling equations are firstly constructed using the fractional order modified SERIF model of order . After that new white noise terms satisfying Wiener process properties are added. The new added diffusion terms are different in shape than used in the first order stochastic modified SEIRF model to reach more probabilistic scenarios covering wide range of probable viral wave dynamics. Dynamical system equations after adding the new stochastic terms are as indicated in Eqs. (16), (17), (18), (19), (20), (21), (22). During creating the white noise terms, balance in equations is assumed which means that if all system equations are mathematically added then both the drift and diffusion terms will vanish as in Eq. (21).

| (16) |

| (17) |

| (18) |

| (19) |

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

where is the exposed-infected diffusion coefficient and is the infected-recovered diffusion coefficient. is the fractional portion of infected-recovered diffusion stochastic term affecting on recovered individuals and similarly is the remaining fractional portion of infected-recovered diffusion stochastic term affecting on deaths individuals.

Fractional order SEIRF models can be solved numerically using many techniques and the used technique here is Euler’s Method [16]. In case of stochastic SEIRF models, Euler- Murayama method is used to solve system numerically [28], [30]. After that, all dynamic models can be applied on the Egyptian case study to predict number of Exposed, Infected, Recovered and Deaths. To estimate dynamic models parameters, first wave transmission rates are used for trial and error estimations based on data in Refs. [24], [25], [32]. In all dynamic models, the second virus wave is assumed that is started in Egypt on 15 November 2020 (day 0).

Results and discussion

All dynamic models are applied on the case study of Egypt to reach different and more realistic scenarios for Egypt second viral wave and time of the peak of each class. The proposed models estimated parameters are reached by trial and error based on the first viral wave transmission rates. The initial point at which dynamic models start to operate is 15 November 2020 (day 0). The fractional order modified SEIRF model is solved numerically using Euler’s method with step time equals 0.001 day. The remaining two stochastic models are solved numerically using Euler- Murayama method with number of paths equals 10 and discretization of time equals 0.001 day, then the average path solution is taken. MATLAB program version 2018b is used to simulate our dynamic models with Core i5 CPU version 6440HQ. The CPU time of computations of each model is as indicated in Table 2 .

Table 3.

Comparison between actual daily infections and predicted ones.

| Days | Dates | Actual daily infected [32] | Predicted daily infections using SEIRF dynamic models |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractional order model |

Stochastic model |

Fractional stochastic model |

|||||||

| α = 0.96 | α = 0.98 | α = 1 | - | α = 0.96 | α = 0.98 | α = 1 | |||

| Day 7 | 22/11/2020 | 351 | 308 | 301 | 294 | 285 | 307 | 303 | 297 |

| Day 14 | 29/11/2020 | 358 | 488 | 460 | 435 | 558 | 488 | 449 | 421 |

| Day 21 | 6/12/2020 | 418 | 802 | 728 | 666 | 743 | 799 | 702 | 690 |

| Day 28 | 13/2/2020 | 486 | 1150 | 1024 | 918 | 1049 | 1140 | 910 | 817 |

| Day 35 | 20/12/2020 | 664 | 1426 | 1261 | 1123 | 1204 | 1324 | 925 | 1025 |

| Day 42 | 27/12/2020 | 1226 | 1588 | 1405 | 1250 | 1154 | 1358 | 1331 | 1071 |

| Day 46 | 31/12/2020 | 1418 | 1631 | 1448 | 1292 | 1184 | 1378 | 1306 | 1160 |

| Day 49 | 3/1/2021 | 1309 | 1644 | 1462 | 1307 | 1162 | 1548 | 1320 | 1243 |

| Day 56 | 12/1/2021 | 970 | 1617 | 1449 | 1304 | 1260 | 1682 | 1553 | 1213 |

| Cumulative infections | 7200 | 10,654 | 9538 | 8589 | 8599 | 10,024 | 8799 | 7937 | |

Table 4.

Comparison between actual daily deaths and predicted ones.

| Days | Dates | Actual daily deaths [32] | Predicted daily deaths using SEIRF dynamic models |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractional order model |

Stochastic model |

Fractional stochastic model |

|||||||

| α = 0.96 | α = 0.98 | α = 1 | – | α = 0.96 | α = 0.98 | α = 1 | |||

| Day 7 | 22/11/2020 | 13 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 14 |

| Day 14 | 29/11/2020 | 15 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 22 | 21 | 19 | 19 |

| Day 21 | 6/12/2020 | 21 | 29 | 27 | 25 | 28 | 30 | 25 | 22 |

| Day 28 | 13/2/2020 | 22 | 50 | 37 | 34 | 38 | 38 | 34 | 33 |

| Day 35 | 20/12/2020 | 29 | 56 | 50 | 45 | 48 | 50 | 58 | 39 |

| Day 42 | 27/12/2020 | 53 | 72 | 63 | 56 | 55 | 61 | 59 | 51 |

| Day 46 | 31/12/2020 | 55 | 81 | 71 | 62 | 61 | 68 | 72 | 52 |

| Day 49 | 3/1/2021 | 64 | 88 | 77 | 67 | 65 | 61 | 77 | 52 |

| Day 56 | 12/1/2021 | 55 | 104 | 89 | 78 | 78 | 63 | 80 | 57 |

| Cumulative deaths | 327 | 515 | 447 | 400 | 409 | 407 | 438 | 339 | |

Table 2.

Dynamic SEIRF models CPU time of computations.

| Dynamic model | Time (sec.) |

|---|---|

| Fractional order model () | |

| Fractional order model | |

| First order model | |

| First order stochastic model | |

| Fractional order stochastic model ( | |

| Fractional order stochastic model ( | |

| Fractional order stochastic model ( |

The initial system values of daily Infected, Recovered and Deaths at day 0 (15 November 2020) are taken from [24], [25], [32]. The initial value of Infected, Recovered and Deaths classes are respectively equal 220, 100, and 10. Egypt total population (N) reached 101 million on 27 October 2020. The initial value of Exposed individuals is assumed 300 persons. All models transmission rates coefficients and stochastic coefficients are estimated for the second viral wave in Egypt and reached results are as indicated in Table 1. The fractional order modified SEIRF model is applied with order equals 0.96, 0.98. Using equals 1 means that the special case of first order modified SEIRF is reached. After that the first order stochastic modified SEIRF model is applied and finally, we apply the fractional order stochastic modified SEIRF model with order equals 0.96, 0.98 and 1.

Table 1.

Dynamic SEIRF models estimated parameters for Egypt.

| Parameter | Notation | Estimated value | Parameter | Notation | Estimated value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial daily transmission rate between Susceptible and Infected | Time coefficient of death rate from Infected to Deaths | ||||

| Initial daily transmission rate between Susceptible and Exposed | Susceptible individuals diffusion coefficient | ||||

| Daily transmission rate time decay controlling parameter | Exposed individuals diffusion coefficient | ||||

| Incubation period | Infected individuals diffusion coefficient | ||||

| Average no. of closed contacts between Susceptible and Infected per day | Recovered individuals diffusion coefficient | ||||

| Average no. of closed contacts between Susceptible and Exposed per day | Deaths individuals diffusion coefficient | ||||

| Initial daily transmission rate from Exposed to Infected | Exposed - Infected diffusion coefficient | ||||

| Time coefficient of transmission rate from Exposed to Infected | Infected - Recovered diffusion coefficient | ||||

| Initial daily cure rate from Infected to Recovered | Fractional part of stochastic term affecting on Recovered individuals | ||||

| Time coefficient of cure rate from Exposed to Infected | Fractional part of stochastic term affecting on Deaths individuals | ||||

| Initial daily death rate from Infected to Deaths |

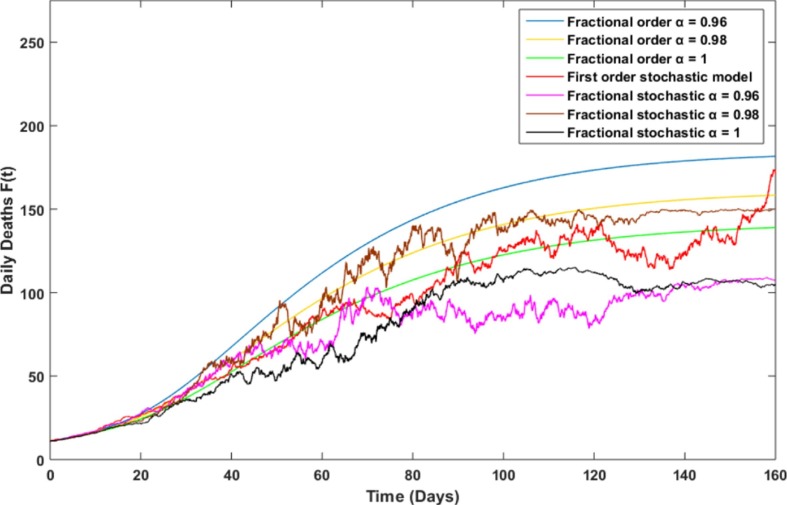

In case of expected Susceptible class, Fig. 1 shows this class variation with days through using different dynamic models. All SEIRF models, except the first order stochastic model, give very near curve shapes. The daily Sucepitable individuals are decreasing with time till forecasting day no. 80 and then they settles with time. The first order stochastic model gives a swinging curve shape of Susceptible class with time. Fig. 2 describes daily expected Exposed individuals under using all SEIRF dynamic models. In case of fractional order dynamic models, when the fractional order increases from 0.96 to 1 the curve peak decreases. Similarly the case in the fractional stochastic dynamic model. Stochastic models not only give different curve peaks but also different time of actions. In case of the stochastic fractional model of order 0.98, the highest expected peak value of daily Exposed individuals is reached. It is expected to be equal 1969 in prediction day no. 35 (20 December 2020). The minimum expected peak is reached by the stochastic fractional model of order 1 with peak equals 1385 in prediction day no. 29 (14 December 2020). Fig. 3 shows different expected dynamic curves for daily Infected class in Egypt under using all proposed dynamic models. The highest viral wave peak is reached by the fractional stochastic model of order 0.96. It is expected to be equal 1752 in prediction day no. 56 (10 January 2021). The lowest peak is reached by the modified SEIRF dynamic model of order 1. It is expected to be equal 1313 in prediction day no. 52 (6 January 2021). The reached dynamics of estimated daily Recovered class are as shown in Fig. 4 . All dynamic curves are increasing with time under using all dynamic models. Number of daily Recovered individuals, without considering dynamic curve of the first order stochastic model, starts to approximately settle with time after prediction day no. 126 (20 March 2021). Daily number of Deaths will also increase with time but with a smaller rate than cure rate as shown in Fig. 5 . Number of daily Deaths individuals, without considering dynamic curve of the first order stochastic model, starts to settle with time after prediction day no. 121 (15 March 2021).

Fig. 1.

Daily Susceptible individuals for Egypt using different dynamic models.

Fig. 2.

Daily Exposed individuals for Egypt using different dynamic models.

Fig. 3.

Daily Infected individuals for Egypt using different dynamic models.

Fig. 4.

Daily Recovered individuals for Egypt using different dynamic models.

Fig. 5.

Daily Deaths individuals for Egypt using different dynamic models.

Predicted scenarios using SEIRF dynamic models are compared with their actual values from [32]. The comparison made for both actual daily infected individuals and daily deaths with their predicted ones. Comparisons are set every 7 days starting from prediction day no. 7 till prediction day no. 56. In comparisons, it is assumed that virus incubation period is 14 days, so comparisons are made each half incubation period. Prediction day no. 46 is also considered in comparisons as it is the actual second viral wave peak [32]. From indicated results in Tables 3 and 4, All dynamic SEIRF models represent useful tools of predictions for scenarios in the cast study of Egypt. The most accurate model here is the fractional stochastic SEIRF model as it predicts cumulative no. of infections, in the proposed prediction days, equals 7937 and the actual no. of cumulative infections equals 7200. In case of no. of deaths, it also gives the highest accuracy of predictions where the actual no. of cumulative deaths equals 327 and the predicted value equals 339.

Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed novel general modified dynamic models to evaluate COVID-19 pandemic. The fractional derivative was used to improve the mathematical modelling of COVID-19 under formulating fractional dynamic models to suggest some possible realistic scenarios. These scenarios will be helpful for public health officials to eradicate this contagious disease. Through generated dynamic models, daily Susceptible (S), Exposed (E), Infected (I), Recovered (R) and Deaths (F) can be predicted. Firstly, we investigated a fractional order modified SEIRF dynamic model of COVID-19 transmission under variable transmission rates assumptions with time. Then proposed model is used to give high accuracy of modelling of COVID-19 with different predicated values of outbreak peaks and scenarios. Adding white noise to these models results in a novel fractional order stochastic dynamic model. After that, all proposed models are applied on the case study of Egypt to predict different scenarios of the second virus wave started on 15 November 2020. Numerical solution of the proposed models is valid through using Euler’s method and Euler-Maruyama method then simulations are made using MATLAB software. From results, both the stochastic modified SEIRF model and the fractional order stochastic modified SEIRF model make daily curves more realistic through adding diffusion terms with different predicted peaks and time of actions. Finally, it has been found out that the reached models are very useful for the Egyptian government to control the COVID-19 outbreak for the upcoming months. Our future work will be focused on fractional stochastic differential equation SEIRF epidemic model with vaccination.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Othman A.M. Omar: Methodology, Software. Reda A. Elbarkouky: Conceptualization, Supervision. Hamdy M. Ahmed: Conceptualization, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the editor and the reviewers for their thoughtful comments and efforts towards improving the quality of our article.

References

- 1.Goyal M., Baskonus H.M., Prakash A. An efficient technique for a time fractional model of lassa hemorrhagic fever spreading in pregnant women. Eur Phys J Plus. 2019;134:1–10. doi: 10.1140/epjp/i2019-12854-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao W., Veeresha P., Prakasha D.G., Baskonus H.M., Yel G. New approach for the model describing the deathly disease in pregnant women using Mittag-Leffler function. Chaos, Solit. Fractals. 2020;134(109696) doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar D., Singh J., Al-Qurashi M., Baleanu D. A new fractional SIRS-SI malaria disease model with application of vaccines, anti-malarial drugs, and spraying. Adv Diff Eq. 2019;278:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13662-019-2199-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah K., Alqudah M.A., Jarad F., Abdeljawad T. Semi-analytical study of Pine Wilt disease model with convex rate under Caputo-Fabrizio fractional order derivative. Chaos, Solit. Fractals. 2020;135(109754) doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109754. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chinazzi1 M, Davis JT, Ajelli M, Gioannini C, et al. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-ncov) outbreak. Science 2020; 368(6489):395–400. DOI: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Hellewell J., Abbott S., Gimma A., Bosse N.I., et al. Feasibility of controlling 2019-ncov outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:488–496. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang N.E., Qiao F. A data driven time-dependent transmission rate for tracking an epidemic: a case study of 2019-nCoV. Science Bulletin. 2020;65(6):425–427. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2020.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang B., et al. Estimation of the transmission risk of the 2019-ncov and its implication for public health interventions. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):462. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang B., et al. An updated estimation of the risk of transmission of the novel coronavirus (2019-ncov) Infect Dis Model. 2020;5:248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carletti M. Mean-square stability of a stochastic model for bacteriophage infection with time delays. Math Biosci. 2007;210(2):395–414. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jovanovic M., Krstic M. Stochastically perturbed vector-borne disease models with direct transmission. Appl Math Model. 2012;36:5214–5228. doi: 10.1016/j.apm.2011.11.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elisabetta T., Stefania M.B., Pasquale V. Stability of a stochastic SIR system. Phys A. 2005;354(C):111–126. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2005.02.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilfer R. World Scientific; New Jersey: 2001. Application of fractional calculus in physics. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed E., Elgazzar A.S. On fractional order differential equations model for nonlocal epidemics. Phys A. 2007;379(2):607–614. doi: 10.1016/j.physa.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yue Y., et al. Modeling and prediction for the trend of outbreak of ncp based on a time-delay dynamic system. Sci Sin Math. 2020;50(3):385. doi: 10.1360/SSM-2020-0026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed A., Salam B., Mohammad M., Ali A., Sarbaz A., Khoshnaw S. Analysis Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) model using numerical approaches & logistic model. Int Open Access J AIMS Bioeng. 2020;7(3):130–146. doi: 10.3934/bioeng.2020013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alrabaiah H., Arfan M., Shah K., Mahariq I., Ullah A. A comparative study of spreading of novel Coronavirus disease by using fractional order modified SEIR model. Alexandria Eng J. 2021;60(1):573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2020.09.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Z, Li X, Liu F, Zhu G, Ma C, Wang L. Prediction of the COVID-19 spread in African countries and implications for prevention and control: A case study in South Africa, Egypt, Algeria, Nigeria, Senegal and Kenya. Science of The Total Environment 2020; 729:138959. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Zhu G., Li X., Su Y., Zhang K., Bai Y., Ma J., et al. Simultaneous parameterization of the two-source evapotranspiration model by Bayesian approach: application to spring maize in an arid region of northwest China. Geosci Model Dev. 2014;7:741–775. doi: 10.5194/gmdd-7-741-2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amar L., Taha A., Mohamed M. Prediction of the final size for COVID-19 epidemic using machine learning: a case study of Egypt. Infect Dis Modelling. 2020;5:622–634. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schüttler J., Schlickeiser R., Schlickeiser F., KrSchöttlerger M. COVID–19 predictions using a gauss model, based on data from April 2. Physics. 2020;2:197–212. doi: 10.3390/physics2020013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bacaër N. Verhulst and the logistic equation (1838), In A Short History of Mathematical Population Dynamics. Springer Ltd.: London, UK 2011; 35–39.

- 23.Khyar O., Allali K. Global dynamics of a multi-strain SEIR epidemic model with general incidence rates: application to COVID-19 pandemic. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020;102:489–509. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05929-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus2019 (Accessed 15.11.2020).

- 25.WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, Who.int 2020. https://covid19.who.int/ (Accessed 15.11.2020).

- 26.Podlubny I. Academic Press; New York: 1999. Fractional differential equations, mathematics in science and engineering. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kilbas A.A., Marichev O.I., Samko S.G. Gordon and Breach; Switzerland: 1993. Fractional integrals and derivatives (theory and applications) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oksendal B. Stochastic differential equations an introduction with applications-six edition. Springer; 2013. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji C., Jiang D. Threshold behavior of a stochastic SIR model. Appl Math Model. 2014;38(21):5067–5079. doi: 10.1016/j.apm.2014.03.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bayram M., Partal T., Orucova B.G. Numerical methods for simulation of stochastic differential equations. Adv Differ Equ. 2018;17 doi: 10.1186/s13662-018-1466-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farid G., Latif N., Anwar M., et al. On applications of Caputo k-fractional derivatives. Adv Differ Equ. 2019;439 doi: 10.1186/s13662-019-2369-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Worldometers, Coronavirus cases 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/Coronavirus/Coronavirus-cases (Accessed 5.2.21).