Abstract

Purpose

To identify the life domains that are most frequently reported to be affected in scoliosis patients undergoing brace treatment.

Methods

A search within the PubMed database was conducted and a total of 60 publications were selected. We classified the studies based on the methods used to measure patients’ quality of life (QoL) and categorized the life domains reported to be affected.

Results

Self-image/body configuration was the most reported affected domain of patients’ QoL, identified in 32 papers, whilst mental health/stress was the second most reported affected domain. Mental health was identified in 11 papers, and 11 papers using the BSSQ questionnaire reported medium stress amongst their participants. Vitality was the third most reported affected domain, identified in 12 papers.

Conclusions

Our review indicates that scoliotic adolescents treated with bracing suffer in their quality of life most from psychological burdens. To improve these patients’ life quality, more attention should be focussed on supporting their mental health.

Keywords: Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, Brace treatment, Quality of life, Self-image

Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is defined as a three-dimensional spinal deformity with a twisting curvature that happens in juveniles of the age from 10 to 20 with no known specific aetiology. Treatment and classification guidelines have been established by the International Scientific Society on Scoliosis Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation (SOSORT) [1–3]. The SOSORT guidelines recommend observation, exercise, brace treatment or surgical treatment based on the severity of curvature.

The efficacy of brace treatment depends on both the quantity (compliance), which is defined as the percentage of actual brace-wearing time relative to the prescribed bracing time [4], and the quality (strap tightness) of brace usage [5]. The quantity of brace usage depends on patients’ own initiative in wearing the brace, where patients tend to be non-complaint reducing wearing time because of physical and psychological issues [4, 6]. This is important because the risk for curve progression and surgery are reduced in patients with good brace compliance [7].

Many factors have been reported to impact the QoL of AIS brace wearers, e.g. back pain, appearance configuration, and mental health [8, 9]. Improving QoL might increase treatment compliance amongst scoliotic brace wearers, positively impacting the treatment quantity. However, in order to effectively improve the QoL of scoliotic brace wearers, we need to know which factors most prominently impact their QoL. Different methods have been applied in measuring the QoL of AIS patients, including standardized (self-assessment) questionnaires and interviews. This paper aims to answer the question: What are the most frequently reported affected domains of QoL of AIS patients under brace treatment?

We answer this question by reviewing the literature on the QoL of AIS patients during brace treatment, and by classifying the literature into 5 groups based on the methods they use to measure patients’ QoL. Based on the reported results, and by comparing the results from papers using similar methods, we identify the most affected domains for AIS brace wearers’ QoL.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

A search within the PubMed database was conducted on June 6, 2019, with the query: “adolescent idiopathic scoliosis AND brace treatment AND quality of life”. Results were not limited by publication date. Studies were excluded if they A) are review papers, B) involved AIS patients under surgical treatment and assessed their QoL, C) were published not as full-text in English.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted from the included publications using a standardized form recording title, authors, sample size, methods, outcome measures and results.

The results of all the reviewed papers were analysed and grouped per patient reported outcome measurement questionnaire. Finally, the most affected domains were identified either based on the authors’ self-report, or if the authors did not explicitly identify the most affected domains, by selecting those domains with QoL results below a threshold value. These threshold values were selected based on the threshold values used by the authors who self-reported on most affected domains. For publications in which the authors concluded that no significant differences were found, neither within different domains of one questionnaire nor within different cohorts using the same questionnaire, we used the classification “No Significance”.

Results

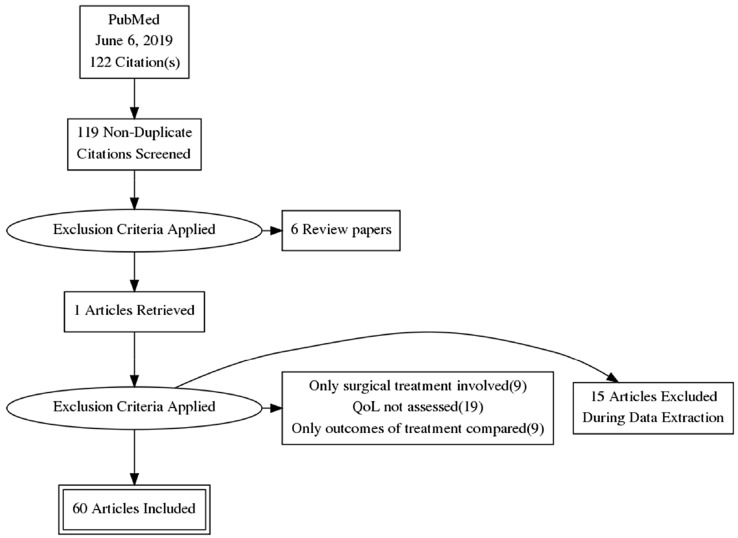

The PubMed search returned 122 papers. Publications were imported from Pubmed into Zotero1 and checked for duplicates. Then, titles and abstracts and potentially eligible publications were screened based on the exclusion criteria by the first author (HW). Candidates were discussed with the second author (DT) and included in the review upon mutual agreement. The articles selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The selection flowchart of the results from the literature search

Table 1 lists the outcomes of all reviewed publications. Overall, self-image/body configuration was the most affected domain of patients’ QoL, mentioned in 32 out of 48 papers measuring self-image. Mental health was the second most affected domain mentioned in 11 out of 49 papers measuring mental health and in 11 out of 11 papers measuring psychological stress. Vitality was the third most affected domain mentioned in 12 out of 21 papers measuring vitality.

Table 1.

An overview of the papers using different methods to measure QoL, indicating the QoL domains that were reportedly most affected by brace wearing

| References | N.(C/E) | Affected domains | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitality | Self-image | Emotional function | General health perception | Physical function | School function | Bodily pain | Social activity | |||

| BrQ | Vasiliadis et al. (Greece), 2006 [10] | 28 | ||||||||

| Kinel et al. (Poland), 2012 [11] | 35 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Aulisa (Italy), 2013 [12] | 108 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Deceuninck et al. (France), 2017 [13] | 40 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Gür et al. (Turkey), 2017 [14] | 28 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Siu Ling Chan et al. (China), 2014 [15] | 42 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Jong Min Lim (Korea), 2018 [16] | 103 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Aulisa et al., 2010 [17] | 108 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Elias Vasiliadis et al., 2008 [18] | 32 | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Rivett et al. (South Africa), 2009 [19] | 31 | √ | √ | |||||||

| Elias Vasiliadis et al., 2006 [20] | 36 | √ | √ | |||||||

| Piantoni et al., 2018 [21] | 43 female |

A:56% NA:44% |

A:72% NA:28% |

|||||||

| In total | 10 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | ||

| BSSQ-Deformity | BSSQ-Brace | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aulisa et al., 2010 [17] | 108 | – | 12.6 | |

| Michalina Zimon et al., 2018 [22] | 63 | 18 | 9.5 | |

| Kinel et al., 2012 [23] | 45 | 15 | 12 | |

| Kotwicki et al., 2007 [24] | 111 female | 18 | 9 | |

| Misterska et al., 2009 [25] | 35 female |

1st evaluation:17.9 2nd evaluation:17.6 |

1st evaluation:11.3 2nd evaluation:10.9 |

|

| BSSQ | Misterska et al., 2011 [26] | 64 |

Urban patients:18.0 Rural patients:17.0 |

Urban patients:12.9 Rural patients:12.3 |

| Leszczewska et al., 2012 [27] | 73 | 19 | 10 | |

| Misterska et al., 2012 [28] | 63 female | 17.61 | 13.06 | |

| Misterska et al., 2013 [29] | 36 female |

1st evaluation:17.7 2nd evaluation:18.0 3rd evaluation:18.1 |

1st evaluation:13.8 2nd evaluation:14.1 3rd evaluation:15.4 |

|

| Xu et al., 2015 [30] | 86 | 15.3 | 13.4 | |

| F. Rezaei Motlagh et al., 2018 [31] | 53 | 15.38 | 12.08 | |

| In total | Medium stress:3 papers | Medium stress:11 papers |

| References | N.(C/E) | Affected domains | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-image | Satisfaction | Mental health | Function activity | Pain | |||

| Aulisa et al., 2013 [12] | 108 | √ | |||||

| SRS-22 | Gür et al., 2018 [14] | 28 | √ | √ | |||

| Chan et al., 2014 [15] | 42 | √ | |||||

| Jong Min Lim et al., 2018 [16] | 103 | √ | |||||

| Aulisa et al., 2010 [17] | 108 | √ | |||||

| Misterska et al., 2013 [29] | 36 female | √ | √ | √ | |||

| F. Rezaei Motlagh et al., 2018 [31] | 53 | √ | √ | ||||

| Cheung et al., 2007 [32] | 46 | √ | √ | ||||

| Schreiber et al., 2015 [33] | 50 | √ | |||||

| Mousavi et al., 2010 [34] | 84 | √ | |||||

| Danielsson et al., 2012 [35] | 77 female | √ | |||||

| Qiu et al., 2011 [36] | 54 | √ | |||||

| Ersen et al., 2016 [37] | 64 | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Lange et al., 2011 [38] | 214 | √ | |||||

| Deceuninck et al., 2012 [39] | 120 | √ | |||||

| Simony et al., 2015 [40] | 73 | √ | √ | ||||

| Yagci et al., 2018 [41] | 20 female | √ | |||||

| Yagci et al., 2019 [42] | 30 female | √ | √ | ||||

| Cheung et al., 2019 [43] | 652 | √ | |||||

| Larson et al., 2019 [44] | 77 | √ | √ | ||||

| Cheung et al., 2016 [45] | 206 | √ | √ | ||||

| Danielsson et al., 2015 [46] | 197 | √ | |||||

| Müller et al., 2011 [47] | 38 | √ | √ | ||||

| In total | 20 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Diarbakerli et al., 2018 [48] | 100 | No significance | |||||

| Paolucci et al., 2017 [49] | 32 | No significance | |||||

| Danielsson et al., 2010 [50] | 459 | No significance | |||||

| Bunge et al., 2007 [51] | 11 | No significance | |||||

| Danielsson et al., 2013 [52] | 52 | No significance | |||||

| References | N.(C/E) | Affected domains | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | Bodily pain | General health | Role limitations due to physical problems | Vitality | General mental health | Role limitations due to emotional problems | Social function | |||

| SF-36 | Qiu et al., 2011 [36] | 54 | √ | |||||||

| Danielsson et al., 2015 [46] | 197(130/67) | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Danielsson et al., 2001 [53] | 216(100/116) | √ | ||||||||

| Danielsson et al., 2003 [54] | 209(100/109) | √ | √ | |||||||

| Freidel et al., 2002 [55] | 146 | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Andersen et al., 2006 [56] | 484(76/408) | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| In total | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Danielsson et al., 2012 [35] | 77(37/40) | No data listed, only compared with outcomes from other questionnaires, no significant differences were found | ||||||||

| Simony et al., 2015 [40] | 73 | Patients got lower score in Physical Composite summary than Mental Composite summary | ||||||||

| Danielsson et al., 2006 [57] | 202 | No significant difference was found in physical functioning and Physical Composite summary | ||||||||

| Measuring methods | Affected domains | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other methods | Schreiber et al., 2015 [33] | 50(25/25) | SAQ | Spinal appearance |

| Carreon et al., 2011 [58] | 1802 | SAQ | Spinal appearance | |

| Schwieger et al., 2016 [59] | 319(120/199) | SAQ | No Significance | |

| Schwieger et al., 2017 [60] | 167 | SAQ | No Significance | |

| Cheung et al., 2019 [43] | 652 | EQ-5D-5L | No Significance | |

| Cheung et al., 2016 [45] | 227 | EQ-5D-5L | Pain | |

| Korovessis et al., 2007 [61] | 103(62/41) | QLPSD | Back flexibility | |

| Pham et al., 2008 [62] | 108(32/76) | QLPSD | Back flexibility | |

| Weigert et al., 2006 [63] | 44 | SRS-24 |

General self-image Satisfaction |

|

| Wibmer et al., 2018 [64] | 41 | SRS-24 | Back functions | |

| Danielsson et al., 2003 [54] | 209(100/109) | GFS | Back functions | |

| Freidel et al., 2002 [55] | 146 | BFW | Self-image | |

| Ugwonali et al., 2004 [65] | 214(136/78) | CHQ | No Significance | |

| Ugwonali et al., 2004 [65] | 214(136/78) | PODCI | No Significance | |

| Zhang et al., 2011 [66] | 25(11/14) | Life Satisfaction Index Z scale(Wood) | No Significance | |

| Zhang et al., 2011 [66] | 25(11/14) | Self-esteem scale(Rosenberg) | Self-esteem | |

| Caronni et al., 2017 [67] | 402 | ISYQOL | No Significance | |

| Topalis et al., 2017 [68] | 609(158/451) | Self-assessment questionnaire | No Significance | |

| Müller et al., 2010 [69] | 2 | Interview | No Significance |

N. (C/E) number of subjects in the control and experimental groups, A somehow affected, NA no affected, BrQ Brace Questionnaire, BSSQ Bad Sobernheim Stress Questionnaire, SRS-22 Scoliosis Research Society-22 Questionnaire, SF-36 The 36-item Short-Form, SAQ Spinal Appearance Questionnaires, EQ-5D-5L EuroQoL 5-dimension 5-level, QLPSD Quality of Life Profile for Spine Deformities, SRS-24 Scoliosis Research Society Instrument for Outcome Assessment 24, GFS General Function Score, BFW Berner Questionnaire for Well-Being, CHQ Child Health Questionnaire, PODCI Paediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument, ISYQOL Italian Spine Youth Qulaity of Life

Discussion

This review classifies the literature based on the method used to measure the QoL and we found that the main affected life domains were self-image, mental health and vitality, which were separately discussed as below.

Self-image

Law et al. [70] found that an aesthetically pleasing brace and the involvement of patients in the design process of the brace were important for increasing user compliance and also addressing psychological issues during treatment. Moreover, patients’ concerns on self-appearance inspired researchers to design flexible braces consisting of elastic straps and a soft shell, which allows more freedom of movement, less physical restrictions, and more importantly, allows to be hidden under clothes. To date, the most widely discussed flexible brace is SpineCor, which was proposed by the Sainte-Justine Hospital [71]. However, the effectiveness of SpineCor remains controversial. Guo et al. [72], Coillard et al. [73] and Wong et al. [74]. found significant differences between SpineCor and rigid brace group in terms of effectiveness. Whilst Gammon et al. [75] reported no significant difference in the treatment outcomes comparing thoraco-lumbar sacral orthosis (TLSO) and SpineCor-treated patients and Coillard et al. [76] demonstrated that SpineCor brace reduced the probability of the progression of early idiopathic scoliosis (15°–30°) after at least 5 years follow-up. However, patients’ acceptance and compliance (which have been shown to have a close correlation with the treatment efficacy [7, 77, 78]) to the SpineCor were comparable to rigid spinal orthoses. The SpineCor brace was also found to be better than TLSO at improving QoL, reported by Ersen et al. [37], patients treated with SpineCor brace have a better self-image, feel more active in daily life and experience less pain according to SRS-22 results. Whilst Misterska et al. [79] found that there was no significant difference in most of the analyzed domains of QoL between patients with the SpineCor brace and the Cheneau brace. Given the currently mixed outcomes of studies on flexible braces, we can conclude that even flexible braces, like SpineCor, has no comparable effectiveness as rigid brace, the merits of improving QoL are promising. A further challenge is in weighing potentially improved QoL against reduced effectiveness.

Mental health

Mental health/psychological stress is defined as the distress AIS patients have because of their deformity or brace. Moreover, the impact of the brace to the self and body image of adolescent is reported as a contributing factor for stress production [80, 81]. This review has found that distress associated with bracing is significantly worse than distress associated with spinal deformity, based on the reviewed literature measuring psychological stress using BSSQ. Andersen et al. [82] found that uncertainty regarding the duration of the brace treatment is one of the reasons causing psychological sequela and they suggested a flexible bracing strategy, such as part-time bracing schemes where patients were urged to participate in sports and social activities without their braces, to avoid social isolation. Lin et al. [83] compared the stress levels of juvenile and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients with brace treatment and found that female adolescents were more vulnerable to depressive psychological status. Higher levels of cognitive function and independence and negative parental attitudes resulted in a greater incidence of depression.

Vitality

Vitality is evaluated by patients’ feelings of energetic and enthusiastic attitudes to daily activities [19], which directly correlates to physical performance. Our findings that show a brace’s impact on vitality corroborate with Daryabor et al. [84], who reported a review on gait and energy consumption of AIS patients treated with orthoses. They found that after 6 months of treatment, excessive oxygen consumption was observed, and results of an endurance test also show a diminished exercise capacity caused by the brace. Moreover, a significant decrease in walking speed and more excessive energy cost were found from the subjects with AIS treated with orthoses versus those without orthoses. They suggested that it could be helpful to intensively train patients with endurance exercises to improve physical performance in AIS.

Limitations

There are three limitations to this review: firstly, the methodology followed in this literature review treats all papers alike, regardless of potential quality differences, since this review aimed to capture the breadth of affected domains of QoL and to provide the results for informing future brace designs. Secondly, a risk of selection bias emerged since the results for RCTs (Randomized Controlled Trial) and non-RCTs are not separately presented to obtain more comprehensive results. RCTs would involve a direct comparison between braced and non-braced patients to provide more robust findings that non-RCTs. Thirdly, the most affected domains of QoL of patients with different severities of scoliosis have not been separated, and more specific details on the affected domains of QoL of patients wearing different braces and under different treatment stages also need to be evaluated.

Conclusion

This paper presented a literature review on the impact of bracing on the Quality of Life of scoliotic adolescents. The results indicate that self-image, mental health, and vitality are the three most frequently reported affected domains. In order to improve the QoL of scoliotic brace wearers, these three domains should be prioritized in researching and designing new bracing treatment options.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.SOSORT guideline committee. Weiss HR, Negrini S, et al. Indications for conservative management of scoliosis (guidelines) Scoliosis. 2006;1(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Negrini S, Donzelli S, Aulisa AG, et al. 2016 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis and Spinal Disorder. 2018;13(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s13013-017-0145-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Negrini S, Aulisa AG, Aulisa L, et al. 2011 SOSORT guidelines: Orthopaedic and Rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis. 2012;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz DE, Durrani AA. Factors that influence outcome in bracing large curves in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2001;26(21):2354–2361. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lou EHM, Hill DL, Raso JV, et al. How quantity and quality of brace wear affect the brace treatment outcomes for AIS. European Spine Journal. 2016;25(2):495–499. doi: 10.1007/s00586-015-4233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karol L, Virostek D, Felton K, et al. Effect of compliance counseling on brace use and success in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2016;98(1):9–14. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.O.00359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brox JI, Lange JE, Gunderson RB, Steen H. Good brace compliance reduced curve progression and surgical rates in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. European Spine Journal. 2012;21(10):1957–1963. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2386-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein SL, Dolan LA, Cheng JCY, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Lancet. 2008;371(9623):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomaszewski, R., Janowska M. (2012). Psychological aspects of scoliosis treatment in children, recent advances in scoliosis, Dr Theodoros Grivas (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-51-0595-4, InTech, Retrieved from: https://www.intechopen.com/books/recent-advances-in-scoliosis/psychological-aspects-of-scoliosis-treatment-in-children.

- 10.Vasiliadis E, Grivas TB, Gkoltsiou K. Development and preliminary validation of Brace Questionnaire (BrQ): A new instrument for measuring quality of life of brace treated scoliotics. Scoliosis. 2006;1(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinel E, Kotwicki T, Podolska A, et al. Polish validation of Brace Questionnaire. European Spine Journal. 2012;21(8):1603–1608. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aulisa AG, Guzzanti V, Galli M, et al. Validation of Italian version of brace questionnaire (BrQ) Scoliosis. 2013;8(1):13. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deceuninck J, Tirat-Herbert A, Rodriguez Martinez N, et al. French validation of the Brace Questionnaire (BrQ) Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2017;12(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s13013-017-0126-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gur G, Yakut Y, Grivas T. The Turkish version of the Brace Questionnaire in brace-treated adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. Prosthetics and Orthotics International. 2018;42(2):129–135. doi: 10.1177/0309364617690393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan SL, Cheung KM, Luk KD, et al. A correlation study between in-brace correction, compliance to spinal orthosis and health-related quality of life of patients with Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Scoliosis. 2014;9(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim JM, Goh TS, Shin JK, et al. Validation of the Korean version of the Brace Questionnaire. British Journal of Neurosurgery. 2018;32(6):678–681. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2018.1501464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aulisa AG. Determination of quality of life in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis subjected to conservative treatment. Scoliosis. 2010;5:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasiliadis E, Grivas TB. Quality of life after conservative treatment of adolescent idiopathic. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2008;135:409–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivett L, Rothberg A, Stewart A, et al. The relationship between quality of life and compliance to a brace protocol in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: A comparative study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2009;10(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasiliadis E, Grivas TB, Savvidou O. The influence of brace on quality of life of adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2006;123:352–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piantoni L, Tello CA, Remondino RG, et al. Quality of life and patient satisfaction in bracing treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders. 2018;13(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13013-018-0172-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimon M, Matusik E, Kapustka B, et al. Conservative management strategies and stress level in children and adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. Psychiatria Polska. 2018;52(2):355–369. doi: 10.12740/PP/OnlineFirst/68744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinel E, Kotwicki T, Podolska A, et al. Quality of life and stress level in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis subjected to conservative treatment. Scoliosis. 2013;8(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotwicki T, Kinel E, Stryła W, et al. Estimation of the stress related to conservative scoliosis therapy: An analysis based on BSSQ questionnaires. Scoliosis. 2007;2(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Misterska E, Głowacki M, Harasymczuk J. Polish adaptation of Bad Sobernheim Stress Questionnaire-Brace and Bad Sobernheim Stress Questionnaire-Deformity. European Spine Journal. 2009;18(12):1911–1919. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misterska E, Głowacki M, Ignys-O’Byrne A, et al. Differences in deformity and bracing-related stress between rural and urban area patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis treated with a Cheneau brace. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 2011;18(2):5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leszczewska J, Czaprowski D, Pawłowska P, et al. Evaluation of the stress level of children with idiopathic scoliosis in relation to the method of treatment and parameters of the deformity. The Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012:1–5. doi: 10.1100/2012/538409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Misterska E, Glowacki M, Latuszewska J. Female patients’ and parents’ assessment of deformity- and brace- related stress in the conservative treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2012;37(14):1218–1223. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31824b66d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Misterska E, Glowacki M, Latuszewska J, et al. Perception of stress level, trunk appearance, body function and mental health in females with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis treated conservatively: A longitudinal analysis. Quality of Life Research. 2013;22(7):1633–1645. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0316-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu X, Wang F, Yang M, et al. Chinese adaptation of the bad sobernheim stress questionnaire for patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis under brace treatment. Medicine. 2015;94(31):e1236. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rezaei Motlagh F, Pejam H, Babaee T, et al. Persian adaptation of the Bad Sobernheim stress questionnaire for adolescent with idiopathic scoliosis. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2018;42:562–566. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1503728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheung KMC, Cheng EYL, Chan SCW, et al. Outcome assessment of bracing in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis by the use of the SRS-22 questionnaire. International Orthopaedics. 2007;31(4):507–511. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0209-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schreiber S, Parent EC, Moez EK, et al. The effect of Schroth exercises added to the standard of care on the quality of life and muscle endurance in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis—An assessor and statistician blinded randomized controlled trial: “SOSORT 2015 Award Winner”. Scoliosis. 2015;10(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s13013-015-0048-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mousavi SJ, Mobini B, Mehdian H, et al. Reliability and validity of the persian version of the scoliosis research society-22r questionnaire. Spine. 2010;35(7):784–789. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bad0e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Danielsson AJ, Hasserius R, Ohlin A, et al. Body appearance and quality of life in adult patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis treated with a brace or under observation alone during adolescence. Spine. 2012;37(9):755–762. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318231493c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiu G, Qiu Y, Zhu Z, et al. Re-evaluation of reliability and validity of simplified chinese version of SRS-22 patient questionnaire: A multicenter study of 333 cases. Spine. 2011;36(8):E545–E550. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e0485e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ersen O, Bilgic S, Koca K, et al. Difference between Spinecor brace and Thoracolumbosacral orthosis for deformity correction and quality of life in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 2016;82(4):710–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lange JE, Steen H, Gunderson R, et al. Long-term results after Boston brace treatment in late-onset juvenile and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis. 2011;6(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deceuninck J, Bernard JC. Quality of life and brace-treated idiopathic scoliosis: A cross-sectional study performed at the Centre des Massues on a population of 120 children and adolescents. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2012;55(2):93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simony A, Hansen EJ, Carreon LY, et al. Health-related quality-of-life in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients 25 years after treatment. Scoliosis. 2015;10(1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13013-015-0045-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yagci G, Ayhan C, Yakut Y. Effectiveness of basic body awareness therapy in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: A randomized controlled study1. Journal of back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2018 doi: 10.3233/BMR-170868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yagci G, Yakut Y. Core stabilization exercises versus scoliosis-specific exercises in moderate idiopathic scoliosis treatment. Prosthetics and Orthotics International. 2019;43:301–308. doi: 10.1177/0309364618820144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheung PWH, Wong CKH, Cheung JPY. An insight into the health-related quality of life of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients who are braced, observed, and previously braced. Spine. 2019;44(10):E596–E605. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000002918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larson AN, Baky F, Ashraf A, et al. Minimum 20-year health-related quality of life and surgical rates after the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine Deformity. 2019;7(3):417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheung PWH, Wong CKH, Samartzis D, et al. Psychometric validation of the EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-Level (EQ- 5D–5L) in Chinese patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders. 2016;11(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13013-016-0083-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Danielsson AJ, Hallerman KL. Quality of life in middle-aged patients with idiopathic scoliosis with onset before the age of 10 years. Spine Deformity. 2015;3(5):440–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muller C, Fuchs K, Winter C, et al. Prospective evaluation of physical activity in patients with idiopathic scoliosis or kyphosis receiving brace treatment. European Spine Journal. 2011;20(7):1127–1136. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-1791-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diarbakerli E, Grauers A, Danielsson A, et al. Health-related quality of life in adulthood in untreated and treated individuals with adolescent or juvenile idiopathic scoliosis. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2018;100(10):811–817. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.00822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paolucci T, Piccinini G, Iosa M, et al. The importance of trunk perception during brace treatment in moderate juvenile idiopathic scoliosis: What is the impact on self-image? Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2017;30(2):203–210. doi: 10.3233/BMR-160733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Danielsson AJ, Hasserius R, Ohlin A, et al. Health-related quality of life in untreated versus brace-treated patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A long-term follow- up. Spine. 2010;35(2):199–205. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181c89f4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bunge EM, Juttmann RE, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis after treatment: Short-term effects after brace or surgical treatment. European Spine Journal. 2007;16(1):83–89. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0097-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Danielsson AJ, Romberg K. Reliability and validity of the swedish version of the scoliosis research society–22 (SRS-22r) patient questionnaire for idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2013;38(21):1875–1884. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a211c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Danielsson AJ, Wiklund I, Pehrsson K, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A matched follow-up at least 20 years after treatment with brace or surgery. European Spine Journal. 2001;10(4):278–288. doi: 10.1007/s005860100309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Danielsson AJ, Nachemson AL. Back pain and function 22 years after brace treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A case-control study—Part I. Spine. 2003;28(18):2078–2085. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000084268.77805.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Freidel K, Petermann F, Reichel D, et al. Quality of life in women with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2002;27(4):E87–E91. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200202150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andersen MO, Christensen SB, Thomsen K. Outcome at 10 years after treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2006;31(3):350–354. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000197649.29712.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Danielsson AJ, Romberg K, Nachemson AL. Spinal range of motion, muscle endurance, and back pain and function at least 20 years after fusion or brace treatment for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A case-control study. Spine. 2006;31(3):275–283. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000197652.52890.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carreon LY, Sanders JO, Polly DW, et al. Spinal appearance questionnaire: Factor analysis, scoring, reliability, and validity testing. Spine. 2011;36(18):E1240–E1244. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318204f987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schwieger T, Campo S, Weinstein SL, et al. Body image and quality-of-life in untreated versus brace-treated females with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2016;41(4):311–319. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schwieger T, Campo S, Weinstein SL, et al. Body image and quality of life and brace wear adherence in females with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Journal of Pediatric Orthopedics. 2017;37(8):e519–e523. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Korovessis P, Zacharatos S, Koureas G, et al. Comparative multifactorial analysis of the effects of idiopathic adolescent scoliosis and Scheuermann kyphosis on the self-perceived health status of adolescents treated with brace. European Spine Journal. 2007;16(4):537–546. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0214-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pham V, Houlliez A, Carpentier A, et al. Determination of the influence of the Cheneau brace on quality of life for adolescent with idiopathic scoliosis. Annales de Readaptation et de Mdecine Physique. 2008;51(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.annrmp.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weigert KP, Nygaard LM, Christensen FB, et al. Outcome in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis after brace treatment and surgery assessed by means of the Scoliosis Research Society Instrument 24. European Spine Journal. 2006;15(7):1108–1117. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0014-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wibmer C, Trotsenko P, Gilg MM, et al. Observational retrospective study on socio-economic and quality of life outcomes in 41 patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis 5 years after bracing combined with physiotherapeutic scoliosis-specific exercises (PSSE) European Spine Journal. 2019;28(3):611–618. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5746-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ugwonali OF, Lomas G, Choe JC, et al. Effect of bracing on the quality of life of adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. The Spine Journal. 2004;4(3):254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang J, He D, Gao J, et al. Changes in life satisfaction and self-esteem in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with and without surgical intervention. Spine. 2011;36(9):741–745. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e0f034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Caronni A, Sciume L, Donzelli S, et al. ISYQOL: A Rasch-consistent questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in adolescents with spinal deformities. The Spine Journal. 2017;17(9):1364–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2017.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Topalis C, Grauers A, Diarbakerli E, et al. Neck and back problems in adults with idiopathic scoliosis diagnosed in youth: An observational study of prevalence, change over a mean four year time period and comparison with a control group. Scoliosis and Spinal Disorders. 2017;12(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13013-017-0125-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Muller C, Winter C, Klein D, et al. Objective assessment of brace wear times and physical activities in two patients with scoliosis. Biomedizinische Technik. 2010;55(2):117–120. doi: 10.1515/BMT.2010.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Law D, Cheung M-C, Yip J, et al. Scoliosis brace design: Influence of visual aesthetics on user acceptance and compliance. Ergonomics. 2017;60(6):876–886. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2016.1227093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Coillard C, Leroux MA, Badeaux J, et al. SPINECOR: A new therapeutic approach for idiopathic scoliosis. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. 2002;88:215–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo J, Lam TP, Wong MS, et al. A prospective randomized controlled study on the treatment outcome of SpineCor brace versus rigid brace for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with follow-up according to the SRS standardized criteria. European Spine Journal. 2014;23(12):2650–2657. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-3146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Coillard C, Leroux M, Zabjek K, et al. SpineCor—A non-rigid brace for the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis: Post-treatment results. European Spine Journal. 2003;12(2):141–148. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0467-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wong MS, Cheng JCY, Lam TP, et al. The effect of rigid versus flexible spinal orthosis on the clinical efficacy and acceptance of the patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine. 2008;33(12):1360–1365. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817329d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gammon SR, Mehlman CT, Chan W, et al. A comparison of thoracolumbosacral orthoses and SpineCor treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients using the scoliosis research society standardized criteria. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2010;30(6):531–538. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181e4f761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coillard C, Circo AB, Rivard CH. A prospective randomized controlled trial of the natural history of idiopathic scoliosis versus treatment with the SpineCor brace. SOSORT Award 2011 winner. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2014;50(5):479–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lou E, Raso JV, Hill DL, et al. Correlation between quantity and quality of orthosis wear and treatment outcomes in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Prosthetics and Orthotics International. 2004;28:49–54. doi: 10.3109/03093640409167925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rahman T, Bowen JR, Takemitsu M, et al. The association between brace compliance and outcome for patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2005;25:420–422. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000161097.61586.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Misterska E, Glowacki J, Kołban M, et al. Does rigid spinal orthosis carry more psychosocial implications than the flexible brace in AIS patients? A cross-sectional study. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2018;32:101–109. doi: 10.3233/BMR-181121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sapountzi-Krepia D, Peterson D, Zafiri V, Iordanopoulou F, et al. The experience of brace treatment in children/adolescents with scoliosis. Scoliosis. 2006;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1748-7161-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sapountzi-Krepia D, Valavanis J, Panteleakis GP, et al. Perceptions of body image, happiness and satisfaction in adolescents wearing a Boston brace for scoliosis treatment. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;35(5):683–690. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Andersen MØ, Thomsen K. Early weaning might reduce the psychological strain of boston bracing: A study of 136 patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis at 35 years after termination of brace treatment. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics Part B. 2002;11(2):96–99. doi: 10.1097/00009957-200204000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lin T, Meng Y, Ji Z, et al. Extent of depression in juvenile and adolescent patients with idiopathic scoliosis during treatment with braces. World Neurosurgery. 2019;125:e326–e335. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Daryabor A, Arazpour M, Samadian M, et al. Efficacy of corrective spinal orthoses on gait and energy consumption in scoliosis subjects: A literature review. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology. 2017;12(4):324–332. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2016.1185649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]