Abstract

Purpose

Although the EQ-5D has a long history of use in a wide range of populations, the newer five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) has not yet had such extensive experience. This systematic review summarizes the available published scientific evidence on the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L.

Methods

Pre-determined key words and exclusion criteria were used to systematically search publications from 2011 to 2019. Information on study characteristics and psychometric properties were extracted: specifically, EQ-5D-5L distribution (including ceiling and floor), missing values, reliability (test–retest), validity (convergent, known-groups, discriminate) and responsiveness (distribution, anchor-based). EQ-5D-5L index value means, ceiling and correlation coefficients (convergent validity) were pooled across the studies using random-effects models.

Results

Of the 889 identified publications, 99 were included for review, representing 32 countries. Musculoskeletal/orthopedic problems and cancer (n = 8 each) were most often studied. Most papers found missing values (17 of 17 papers) and floor effects (43 of 48 papers) to be unproblematic. While the index was found to be reliable (9 of 9 papers), individual dimensions exhibited instability over time. Index values and dimensions demonstrated moderate to strong correlations with global health measures, other multi-attribute utility instruments, physical/functional health, pain, activities of daily living, and clinical/biological measures. The instrument was not correlated with life satisfaction and cognition/communication measures. Responsiveness was addressed by 15 studies, finding moderate effect sizes when confined to studied subgroups with improvements in health.

Conclusions

The EQ-5D-5L exhibits excellent psychometric properties across a broad range of populations, conditions and settings. Rigorous exploration of its responsiveness is needed.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11136-020-02688-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: EQ-5D, EQ-5D-5L, Systematic review, Health-Related Quality of Life, Psychometric properties

Background

The EQ-5D is a broadly used generic multi-attribute health utility instrument. In addition to a thermometer-like visual analog scale (VAS) anchored by 0 (worst imaginable health) and 100 (best imaginable health), the EQ-5D’s descriptive system comprises five dimensions with one item per dimension: mobility (MO), self-care (SC), usual activities (UA), pain/discomfort (PD) and anxiety/depression (AD). Responses to these items can be converted into a single measure of health utility using preference-based (typically country-specific) weights. Preference weights are derived from preference elicitation studies using hypothetical EQ-5D health profiles [1], typically sampling a general population.

Until 2005, respondents could select from three response levels of function or symptoms for each dimension (the EQ-5D-3L; 3L). However, due to evidence of notable ceiling effects of the EQ-5D-3L in some populations [2–5] and concerns regarding the instrument’s sensitivity to certain patient-relevant changes [6–10], a five response level version of the instrument was developed by the EuroQol group in 2010 [11, 12]. The five-level version (EQ-5D-5L; 5L) added two response levels: one between “no problems” (level 1) and “moderate/some problems” (level 2 in 3L, level 3 in 5L), and another one between “moderate/some problems” and “severe problems” (level 3 in 3L, level 5 in 5L). The EQ-5D-5L also updated the middle response level with the term “moderate” from the EQ-5D-3L’s “some” for the first three dimensions, while the most severe response level for MO was changed from “confined to bed” to “unable to walk about”. Additionally, the instructions for marking overall health today on the visual analog scale (VAS) were different between the two versions until 2019. The EQ-5D-5L is currently available for more than 130 languages [13] and has been formally tested against the EQ-5D-3L in numerous studies, demonstrating improved psychometric properties over the EQ-5D-3L [14]. An interim scoring strategy that applies existing EQ-5D-3L preference weights to EQ-5D-5L can be used if EQ-5D-5L preference weights for certain populations are not yet available [A4].

Although its use has expanded to a wide range of settings and research purposes, there is no study reporting a comprehensive review of the measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L. This review will be informative for researchers interested in economic evaluation and preference measurement, decision makers, users of EQ-5D-5L as patient-reported outcome measure for improving health care, and readers who need to interpret the findings from studies incorporating the EQ-5D-5L. The 5L instrument has now enjoyed over a decade of use and this paper aims to summarize the existing evidence on the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L. A second objective of this review is to identify knowledge gaps regarding the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L, and to highlight important areas for future research.

Methods

This literature search and review was guided by the PRISMA guidance on systematic reviews and meta-analyses [15]. This review focuses on the descriptive system of the EQ-5D-5L (the five items) as it was not always clear which version of the EQ-VAS was used in extracted studies.

Literature search

Four online databases—PUBMED (MEDLINE), PsycINFO, Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE), and the EuroQol website—were searched using pre-determined terms: “EQ-5D,” “EQ-5D-5L,” “5L,” “EuroQol” and “5 Level.” The search included publications up to January 2019. Duplicates were assessed using author names, titles and journals. Exact search strategy and terms can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Two screening phases were conducted: (1) title and abstract, and (2) full text. Two researchers experienced in psychometric research methods and the EQ-5D instruments (IB and YF) independently screened the publications and reached consensus on any disagreements to determine inclusion. When consensus could not be reached, two senior researchers with extensive experience in psychometric research, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measurement and the EQ-5D instrument were consulted for a final decision (TK and MFJ).

The a priori exclusion criteria were:

does not study humans 18 years or older;

publication language is other than German or English;

study does not assess the official version of the EQ-5D-5L or an experimental version of the 5L was used;

published prior to 2005 (prior to development of the 5L);

not a peer-reviewed primary study, literature review or conference paper (conference papers were included but other conference proceedings such as presentations or posters were excluded); and

not evaluating the measurement and psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L.

Data extraction

Publications selected for inclusion were reviewed and data entered into pre-determined tables by either YF or IB. Sometimes, values needed to be estimated from available information. When information on means and standard deviations were not available, but other sufficient data were reported (such as range or median), the mean and standard deviations were estimated using recommendations from Wan et al. 2014 [16]. When multiple studies use the same underlying dataset, data was extracted only once (e.g., [A20, A26, A31, A36–A38, A49, A53, A77, A79, A96]). General study characteristics including sample size, study design, sample characteristics and version of EQ-5D-5L were extracted, as were information on distributional properties such as means, percent reporting best health (“no problems” on dimensions or ‘11111’ across the health profile), percent reporting worst health (“extreme” or “unable to” on dimensions or ‘55555’ across the health profile) and missing values, for dimensions as well as the health profile. Although no guidance for level of missing values indicate the feasibility of an instrument, ≤ 5% has been found to be acceptable for multiple imputation [17]. Missing values ≤ 5% and floor ≤ 15% are considered acceptable [18].

Reliability is the consistency of an instrument, internally (extent to which subscale items are interrelated) as well as the instrument’s stability across time (whether the instrument produces similar results in stable environments). Internal consistency is not a relevant psychometric property for the EQ-5D instruments and therefore we did not include it in this review. Agreement between two applications of the instrument over a period of time over which it should be stable (test–retest) is usually evaluated using Cohen’s Kappa (κ) for categorical items (EQ-5D-5L items) or ICC for continuous values (EQ-5D-5L index value), with a level of ≥0.8 and ≥0.7 determined as acceptable, respectively [19–21]. We relied on the guidance from Cicchetti 1994 [22] to define Kappa and ICC: < 0.40 = poor, 0.40–0.59 = fair, 0.60–0.74 = good, 0.75–1.00 = excellent. Other methods such as area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) were also reported [23, 24].

In general, validity refers to the degree to which a measurement tool captures the underlying construct of interest. We extracted all information regarding different forms of validity from included publications, the most commonly investigated being convergent validity (a specific subtype of construct validity), that examines how closely two instruments that are intended to measure the same construct are related. This is most often done by testing the correlation between the EQ-5D-5L and other measures of health or health-related quality of life (including those measuring pain, and mental or physical health or HRQoL). Other validity results extracted include known-groups validity (examining whether the 5L can distinguish between a priori determined groups).

Responsiveness is the ability of an instrument to capture true changes (e.g., due to a health intervention) in the construct of interest over time. Some argue that responsiveness is a subtype of validity or reliability [25]. Responsiveness is of particular importance for the EQ-5D-5L: one of the reasons the instrument was created was to address criticisms that the EQ-5D-3L was not sufficiently sensitive to change [26]. Responsiveness can be specific to population, context, and depends on the direction of change in the underlying construct [27]. In the case of the EQ-5D-5L, responsiveness addresses the question if the index value or individual items can detect relevant changes in underlying health. Preliminary research conducted on experimental five-level versions of the EQ-5D found its index value to be sensitive to change. Commonly used methods evaluating responsiveness include standardized effect size (SES) and/or standardized response mean (SRM) [25, 27, 28]. Both standardize the difference in means from two measurement points by dividing by standard deviation (of the mean or of the change scores). An SES of 0.2 to 0.3 is considered small, ≈ 0.5 medium and ≥ 0.8 large effect sizes [29]. Some studies examined the EQ-5D-5L’s ability to detect a change as defined by external criteria, or anchor, to estimate minimally important differences (MID) or the smallest change in score that is beneficial or relevant for patients [27, 28, 30]. The external anchor is usually a patient-assessment.

Analysis

Due to the heterogeneity of studies and outcomes included, we were only able to summarize three outcomes across studies: proportion of respondents reporting the best health, mean index values, and EQ-5D-5L’s correlations with other measures (Spearman’s or Pearson’s Rho). When multiple index scores are reported in a study, the most up to date (EQ-5D-5L as opposed to the interim or ‘crosswalk’) or most appropriate (closest to the sampled population) index scores were extracted. The signs of correlation coefficients were changed if authors had not corrected for the directionality of the scales. Subgroup analysis was performed when there were at least three studies representing a relevant subgroup.

Data were pooled by means of random-effects models using inverse variance weight for pooling. Pooling was based on Fisher’s z transformation of correlation coefficients and logit transformation of proportions. Microsoft excel was used for data extraction, while R was used for data analysis [31]. The R package “meta” was used to estimate pooled values [32].

Results

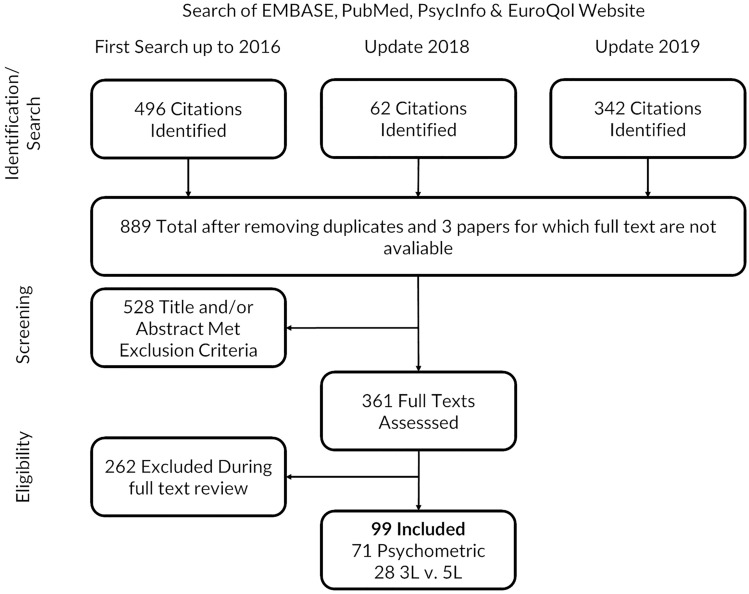

We identified 496 papers during the initial search and additional 397 papers during the updates in 2018 and 2019, of which 99 papers were included for review (Fig. 1; reference list A). These papers included general population (n = 32) and patients (n = 58) from 32 countries (see Table 1). The country where the most numerous studies were conducted was the UK/England (n = 18), while Canada, Germany, Singapore and the USA were the locations with the second most numerous studies (n = 8 each). The patient groups represented by the most studies are musculoskeletal/orthopedic (n = 8), cancer (n = 8) and lung/respiratory diseases (n = 7). The Multi-Instrument Comparison study (MIC) [A20, A26, A31, A36–A38, A49, A53, A77, A79, A96] and the study that developed a method of deriving 5L interim index values from 3L value sets [A4, A6, A83] were represented by 11 and 3 studies, respectively. General characteristics of included studies can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Fig. 1.

Literature search and inclusion/exclusion results

Table 1.

Psychometric properties of EQ-5D-5L

| First author publication year [reference] | Country | Disease area/study population | Floora > 15% |

Missing ≥ 5% |

Test–retest ICC, Cohen’s kappa (κ)c | Known-group validityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal diseases and orthopedic patients | ||||||

| Buchholz 2015 [A23] | GER | Orthopedic, psychosomatic, rheumatologic rehabilitation patients | No | No | ||

| Conner-Spady 2015 [A24] | CA | Osteoarthritis, referred for total joint replacement | No | No |

ICC Index: excellent Kappa: MO good; SC excellent; UA good; PD good; AD excellent |

|

| Greene 2015 [A29] | USA | Patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty | No | |||

| Whitehurst 2016 [A56] | CA | Spinal cord injury | MO & SC | |||

| Bilbao 2018 [A68] | ESP | Hip or knee osteoarthritis | No | No | Statistically sign. difference across WOMAC scores and self-rated health | |

| Cheung 2018 [A72] | CN | Patients attending a back pain clinic | No | No | Statistically sign. over disc degeneration and spinal surgery, but not other spine-related factors or pain | |

| Conner-Spady 2018 [A73] | Manitoba, CA | Osteoarthritis; 1 year following total joint replacement | No | ICC: excellent | ||

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Pan 2014 [A34] | CN | Outpatients with type 2 diabetes mellitus | No | |||

| Pattanaphesaj 2015 [A35] | TH | Diabetes; treated with insulin | No | No |

ICC: good Kappa: MO fair; SC nr; UA fair; PD fair; AD fair |

|

| Wang 2015 [A42] | SG | Type II diabetes | No | |||

| Wang 2016 [A55] | SG | Diabetes | No | |||

| McClure 2018 [A87] | CA | Type II diabetes | No | |||

| Cancer | ||||||

| Kim 2012 [A2] | Korea | Cancer patients receiving ambulatory chemotherapy | No |

ICC: excellent Kappa: MO good; SC good; UA fair; PD fair; AD fair |

||

| Lee 2013 [A9] | SG | Histologically confirmed breast cancer | Across Oncologist, Patient evaluated performance status, treatment mode, and evidence of disease | |||

| Kouwenberg 2019 [A98] | NL | Breast reconstruction/mastectomy patients | Across radiotherapy type, surgery group and age | |||

| Skin diseases | ||||||

| Swinburn 2013 [A12] | UK | Psoriasis | Trending as expected across skin-specific questionnaires (DLQI and SAPAPSI) | |||

| Poor 2017 [A63] | HU | Psoriasis | No | No | Not sign. across age groups, but sign. across gender. | |

| Yfantopoulos (2017a) [A64] | GR | Psoriasis | No | |||

| Tamasi 2018 [A90] | HU | Pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus | Statistically sign. across severity of disease, symptoms and comorbidities. Not across gender or treatment status | |||

| Stroke | ||||||

| Golicki 2015 [A27] | PL | Stroke | No | Trends as expected across age, modified Rankin Scale, Barthel Index, Stroke type | ||

| Golicki 2015 [A28] | PL | Stroke | MO, SC, UA at baseline | No | ||

| Chen 2016 [A46] | Taiwan | Stroke | Only SC | |||

| Mental health diseases | ||||||

| Mihalopoulos 2014 [A20] | AU, UK, USA, CN, NOR, GER | People reporting depressive symptoms [MIC]e | Strongly across levels of depression | |||

| Camacho 2018 [A70] | UK | Mental health conditions | No | |||

| Engel 2018 [A77] | AU, CA, GER, NOR, UK, USA | Depression [MIC]e | Statistically sign. between healthy and depressive samples: effect size is large | |||

| Cardiovascular diseases | ||||||

| White 2015 [A43] | UK | Symptomatic cardiac arrhythmia before and after cardiac ablation | ICC: excellent | |||

| Chuang 2019 [A94] | FR, AT, GER, I, ESP, CH, UK | Acute pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis | No | No | Moderately across embolism types | |

| Gao 2019 [A96] | AU, CA, GER, NOR, UK, US | Heart disease | Statistically sign. differences across age, gender, education and MacNew Heart Disease scores | |||

| Lung diseases | ||||||

| Lin 2014 [A19] | USA | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||||

| Szentes 2018 [A89] | GER | Interstitial lung diseases | No | |||

| Hernandez 2019 [A97] | UK, FR | Asthma | Moderately to strongly with medication use and asthma control | |||

| Liver diseases | ||||||

| Scalone 2011 [A1] | I | Different severe chronic hepatic diseases | No | No | ||

| Scalone 2013 [A10] | I | Chronic hepatic diseases | No | |||

| Jia 2014 [A18] | CN | Inpatients with hepatitis B | No |

ICC: Excellent Kappa: MO excellent; SC good; UA excellent; PD excellent; AD excellent |

||

| Blood diseases | ||||||

| Batt 2018 [A66] | USA | Hemophilia | Statistically sign. across age, employment, cohabitation, existence of chronic conditions and pain. Not sign. across education, BMI groups, cohabitation, Hemophilia severity, treatment type | |||

| Buckner 2018 [A69] | USA | Hemophilia B and caregivers of children (< 18 years) with hemophilia B | Statistically sign. differences across self-reported anxiety, depression, arthritis, pain, age, hemophilia severity, functional status | |||

| Kidney diseases | ||||||

| Yang 2015 [A44] | SG | Diagnosis of End-stage renal disease on Peritoneal or hemodialysis | No | Strongly across comorbidity categories and symptoms, but weakly across dialysis adequacy, hemoglobin levels and burden | ||

| Thaweethamcharoen 2018 [A91] | TH | Patients on peritoneal dialysis | ||||

| Central nervous system diseases | ||||||

| Garcia-Gordillo 2014 [A16] | ESP | Parkinson’s disease | No | |||

| Fan 2018 [A78] | UK | Parkinson’s Disease | No | |||

| Other patient types and studies that incorporate several disease groups | ||||||

| Tran 2012 [A3] | VN | Diagnosis of HIV/AIDS | No | |||

|

van Hout 2012 [A4] Janssen 2013 [A6] |

DK, UK, NL, PL, I, SCO | Crosswalk studyd | No | No | Moderately with age and smoking, not with education | |

| Craig 2014 [15] | USA | Patients with chronic conditions from a national representative sample of adults | No | |||

|

Richardson 2015 [A37] Mitchell 2015 [A31] |

AU, CA, GER, NOR, UK, USA | MIC studye | Strongly across different chronic disease groups vs. healthy | |||

| Sakthong 2015 [A39] | TH | Outpatient patients taking continuous medication at least 3 months for 14 disease groups | No |

ICC index: excellent Kappa: MO good; SC fair; UA fair; PD fair; AD fair |

Statistically sign. across age, gender, education, employment, self-rated health, comorbidities, number of medicines and perception of disease control | |

| Lamu 2016 [A49] | AU, CA, GER, NOR, UK, USA | MIC studye | Weakly with subjective well-being | |||

| Rogers 2016 [A54] | UK | Deaf persons using British sign language | No |

ICC: excellent Kappa: MO good; SC fair; UA fair; PD good; AD fair |

Weakly to moderately with CORE 10, CORE 6D | |

| Fermont 2017 [A59] | UK | Severe and complex obesity; undergoing bariatric surgery | Not statistically sign. across BMI levels (Above and under 50) or those with comorbidities versus those without. | |||

| Bewick 2018 [A67] | UK | Chronic rhino sinusitis patients | No | |||

| Easton 2018 [A75] | AU | Older residents of care facilities with dementia or cognitive impairments and proxies | Moderate to small differences across cognition scores and modified Barthel index categories | |||

| Janssen 2018 [A83] | PL, DK, England, I, SCO, NL | Crosswalk studyd | Only UA | |||

| Kohler 2018 [A84] | India | Post vaginal birth or cesarean section | MO, SC, UA only at baseline | |||

| Gandhi 2019 [A95] | SG | Cataract surgery | No | |||

| Rencz 2019 [A99] | HU | Crohn’s disease | No | No | Statistically sign. differences across age groups and chronic conditions | |

| General population | ||||||

| Kim 2013 [A8] | KOR | Nationally representative general population |

ICC: excellent Kappa: MO good; SC poor; UA good; PD fair; AD poor |

|||

| Agborsangaya 2014 [A13] | CA | General population | No | No | ||

| Hinz 2014 [A17] | GER | General population | No | |||

| Feng 2015 [A25] | England | General population | No | |||

| Mulhern 2015 [A32] | UK (Yorkshire) | General adult population | No | |||

| Scalone 2015 [A40] | I | General population; quota sampling | No | |||

| Augustovski 2016 [A45] | Uruguay | General population; sampling quotas by location | No | |||

| Ferreira 2016 [A47] | Portugal | Students from 2 universities aged 30 years or under | No | No | Statically sign. across gender, health condition, labor situation, marital status | |

| McCaffrey 2016 [A50] | AU | South Australian general population | No | |||

| Oremus 2016 [A52] | CA | Toronto area general population | No | |||

| Huber 2017 [A60] | GER | General population | No | |||

| Konnopka 2017 [A61] | GER | General population | Each dimension sign. distinguished between categories of “dimension-specific” indicators; Index statistically sign. across age, education, diseases but not marital status | |||

| Nguyen 2017 [A62] | VN (Hanoi) | Randomly selected resident adults of the city of Hanoi | No | Sign. across age, occupation, education, income, symptoms, chronic conditions; not Over health services usage | ||

| Yfantopoulos 2017b [A65] | GR | General middle-aged and elderly population | No | No | Statistically sign. across age, gender and smoking status | |

| Purba 2018 [A88] | Indonesia | Indonesian representative population | No | Assessed Gwet’s AC, acceptable for dimensions. ICC low (0.37) for index | Statistically sign. across age, ethnicity and gender, but not across residence, education, income or religion. | |

| Hernandez 2018 [A81] | ESP | Spanish National Health Survey 2011–2012 | No | |||

| Marti-Pastor 2018 [A86] | ESP | Representative general population | No | |||

| Ge 2019 [A80] | SG | Young (21–44 years), middle-aged (45–64 years), older adults (≥ 65 years) | ||||

| Proxies | ||||||

| Bhadhuri 2017 [A57] | UK | Family members of meningitis survivors | ||||

Sign. significant(ly)

AU Australia, AT Austria, CA Canada, CH Switzerland, CN China, DK Demark, ESP Spain, FR France, GER Germany, GR Greece, HU Hungary, I Italy, KOR South Korea, NL Netherlands, NOR Norway, PL Poland, SCO Scotland, SG Singapore, TH Thailand, UK United Kingdom, USA United States of America, VN Vietnam

Blank cells imply that the study did not investigate and/or report on the psychometric property

aFloor defined as reporting worst health response levels 5 (“extreme problems” or “unable to”) for EQ-5D-5L items (Mobility MO, Self-Care SC, Usual Activities UA, Pain/Discomfort PD, Anxiety/Depression AD) and on the profile (‘55555’). When not specified, reports of the worst health level for all dimensions and the profile were below 15%

bGenerally assessed with effect size or tests of difference in means

cKappa and ICC defined as [22]: (1) < 0.40 = poor. (2) 0.40–0.59 = fair. (3) 0.60–0.74 = good. (4) 0.75–1.00 = excellent

dCrosswalk study include: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma, diabetes, liver disease, (rheumatoid) arthritis, cardiovascular disease, stroke, depression, personality disorders, students

eMultiple Instrument Comparison (MIC) study includes: arthritis, asthma, cancer, depression, diabetes, hearing loss, heart disease (from AU, CA, GER, NOR, UK, USA)

Table 2.

Responsiveness of EQ-5D-5L index values

| First author year [reference] | Patient/population group | Value set | Improved | Stable | Deteriorated | All | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SES | SRM | SES | SRM | SES | SRM | SES | SRM | |||

| Studies using a value set for the 3L version of the EQ-5D/interim scoring method | ||||||||||

| Lee 2013 [A9] | Singaporean breast cancer patients at baseline and 1 week later: regressed with self-reported performance status | Interim scoring method [A5] Japanese 3L value set | 0.54b | |||||||

| Singaporean breast cancer patients at baseline and 1 week later: regressed with self-reported quality of life | 0.69b | |||||||||

| Swan 2013 [A11] | Patients before and after colonoscopy screening | Interim scoring method [A5] Unclear which 3L value set was used | 0.50 | 0.44 | ||||||

| Jia 2014 [A18] | Hepatitis B patients at baseline and 1 week after | Interim scoring method [A5] Chinese 3L value set | Absolute increase of 0.029–0.073 for index values for the subsample of patients with improved health. There is not enough information to calculate the SES. | |||||||

| Golicki 2015 [A28] | Stoke patients initial hospitalization and 4 mo after therapy: mRS-based criterion | Interim scoring method [A5] Polish 3L value set | 0.51 | 0.69 | − 0.25 | − 0.25 | ||||

| Stoke patients initial hospitalization and 4 mo after therapy: Barthel index-based criterion | 0.71 | 0.86 | − 0.40 | − 0.47 | ||||||

| Chen 2016 [A46] | Stroke patients before and 3 to 4 weeks after therapy | Interim scoring method [A5] Japanese 3L value set | 0.40 | 0.63 | ||||||

| Conner-Spady 2018 [A73] | Pre to 1 year post TJR (hip) | Interim scoring method [A5] UK 3L value set | 1.86 | 1.53 | ||||||

| Pre to 1 year post TJR (knee) | 1.19 | 1.04 | ||||||||

| Kohler 2018 [A84] | Vaginal birth 3 to 7 days postpartum | Interim scoring method [A5] UK 3L value set | 0.78a | |||||||

| Vaginal birth 21 to 30 days postpartum | 1.18a | |||||||||

| Cesarean Sect. 3 to 7 days postpartum | 0.90a | |||||||||

| Cesarean Sect. 21 to 30 days postpartum | 1.65a | |||||||||

| Gandhi 2019 [A95] | Before and after cataract surgery | Interim scoring method [A5] Singaporean & English 3L value sets | 0.25 | 0.23 | ||||||

| Before and after cataract surgery | 0.26 | 0.23 | ||||||||

| Studies using a value set for the 5L version of the EQ-5D | ||||||||||

| Sakthong 2015 [A39] | Patients of university hospitals 1 to 2 weeks apart | Thai 5L value set | 0.33 | − 0.29 | ||||||

| Nolan 2016 [A51] | COPD outpatients before and 8 weeks after pulmonary rehabilitation | English 5L value set | 0.27a | |||||||

| Fermont 2017 [A59] | Patients with severe/complex obesity before and 6 mo after bariatric surgery | English 5L value set | 0.25 | 0.30a | − 0.08 | − 0.09a | 0.16 | 0.19 | ||

| Bilbao 2018 [A68] | Patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis from hospital/clinic visit and 6 mo after | Spanish 5L value set | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.39 | 0.42 | ||

| Campbell 2018 [A71] | 3 mo after bariatric surgery | English 5L value set | 0.40a | |||||||

| 1 year after bariatric surgery | 0.32a | |||||||||

| McClure 2018 [A87] | Baseline to 1 year after: longitudinal study of diabetes patients | Canadian 5L value set | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.44 | ||||

| Wijnen 2018 [A93] | Epilepsy patients pre intervention program to 12 mo after | Dutch and English 5L value sets | −0.017 | −0.023 | ||||||

| Chuang 2019 [A94] | Baseline to 1 year after: longitudinal study of venous thromboembolism patients | English 5L value set | 0.44 | |||||||

| Baseline to 1 year after: longitudinal study of venous thromboembolism patients | 0.55 | |||||||||

| Studies not reporting which value set was used | ||||||||||

| White 2016 [A43] | UK patients with cardiac arrhythmias pre and 8–16 weeks post catheter ablation | Not reported | − 0.22 | − 0.29 | ||||||

| Bhadhuri 2017 [A57] | Non-carers of meningitis survivors 1 year apart | Not reported | 0.01 | − 0.19 | − 0.14 | |||||

| Carers of meningitis survivors 1 year apart | 0.19 | − 0.02 | − 0.27 | |||||||

| Carers with fewer hours of care of meningitis survivors 1 year apart | − 0.16 | 0.05 | − 0.31 | |||||||

When papers reported multiple results for responsiveness, the SES and SRM are reported in this table for comparability. SES standardized effect size, SRM standardized response mean, QoL quality of life, yr year, mo month, TJR total joint replacement

aEffect size was calculated from available information in the paper

bPaper calculated effect size using regression methods:

Distribution properties

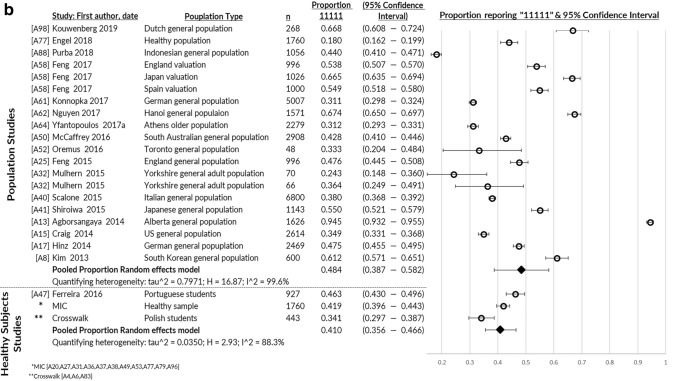

Missing values (17 of 17 papers) and most severe health state (43 of 48 papers) were under 5% and 15%, respectively, showing the 5L to be feasible and free from floor effects (Table 1). Studies with greater than 15% reporting the most severe health (in certain dimensions) were those studying patients with stroke [A28, A46], spinal cord injury [A56], women just after giving birth [A84] and patients with chronic illnesses [A83]. These patients were reporting severe health impairments in MO, SC, and/or UA. Enough information was reported by 48 studies to pool proportion reporting the best health state ‘11111,’ which was 23% for patients, ranging from 2% (musculoskeletal diseases) to 36% (cancer; Fig. 2a). Pooled proportion of over 15% at full health was observed for patients with diabetes, cancer, liver diseases, kidney diseases and skin diseases. General and healthy population studies were 48% and 41% reporting full health, respectively (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

a Proportion reporting no problems on the EQ-5D-5L profile “11111”: pooled across health conditions. b Proportion reporting no problems on the EQ-5D-5L profile “11111”: pooled for general and healthy populations

By dimension, proportions reporting “no problems” were smallest across the board for stroke, while SC consistently had large ceilings except for patients with stroke, diseases of the nervous system and diseases of the musculoskeletal system (pooled proportion reporting “no problems” in EQ-5D-5L dimensions can be found in Supplementary Table 3). Konnopka and Koenig (2017) also found SC to be most problematic in terms of percentage at the ceiling, even for those reporting four or more diseases and needing one or more hours of daily care [A61].

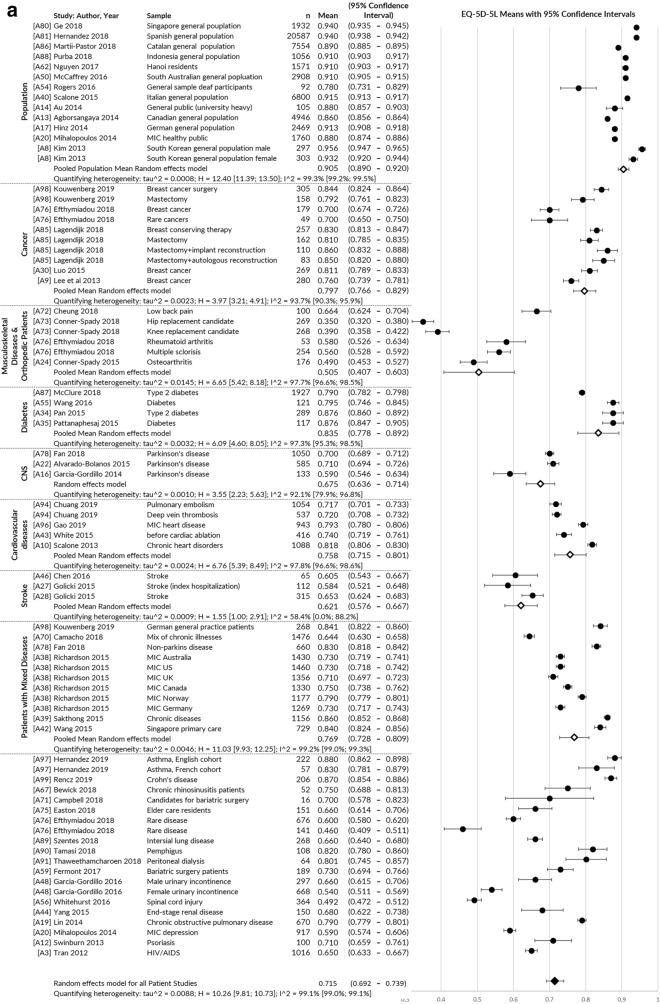

Index value means could be pooled from 58 publications, showing they were generally lower for disease groups than healthy populations and lower socio-economic/socio-demographic groups than higher (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3.

a EQ-5D-5L index value mean: pooled across health conditions. b EQ-5D-5L index value mean: pooled across education level and employment status

Reliability

Nine papers addressed test–retest reliability, eight found the scale agreement (ICC) excellent and the remaining study finding an ICC of 0.7. However, five studies found fair agreement on the item level (Cohen’s Kappa) for certain dimensions: they tend to be smaller for PD and highest for MO (Table 1).

Validity

Studies examining construct validity typically compared the EQ-5D-5L to the EQ-5D-3L: the focus has been on the response categories as the items themselves were identical. As we did not include studies with experimental versions of the 5L, most of the earlier studies examining the construct validity of various response options of the 5L have not been included. One included study used exploratory factor analysis to examine the structure of the EQ-5D-5L, Satisfaction with Life Scale and MacNew questionnaire [A96]. They found MO, SC, UA, and PD to load onto one factor with other physical health and usual activity items, and AD to load onto a second factor including items addressing mood, depression, and confidence. Of the five included papers addressing content validity, three used qualitative methods. Keeley et al. (2013) sampled research professionals who found the SC item to be too narrowly defined and the UA item to be too broad, while deeming PD and AD as the most relevant dimensions related to health-related quality of life [A7]. Whitehurst et al. (2014) sampled patients with spinal cord injuries, who generally found the 5L to be relevant for their health problems [A21]. However, some found the instrument to lack coverage of specific aspects of spinal cord injury. A more recent qualitative study found the EQ-5D-5L to lack relevancy for asthma patients except for some physical limitations, but also praised the instrument for its generic nature [A92].

Craig et al. (2014) found via regression analysis that the 5L encompasses a slightly larger range of EQ-VAS scores from best to worst health state compared to the 3L [A15]. Janssen et al. 2018 also investigated the distance between the 3L and 5L levels using a direct approach asking patients to place the labels onto a horizontal VAS scale, finding a larger range covered by the 5L [A83].

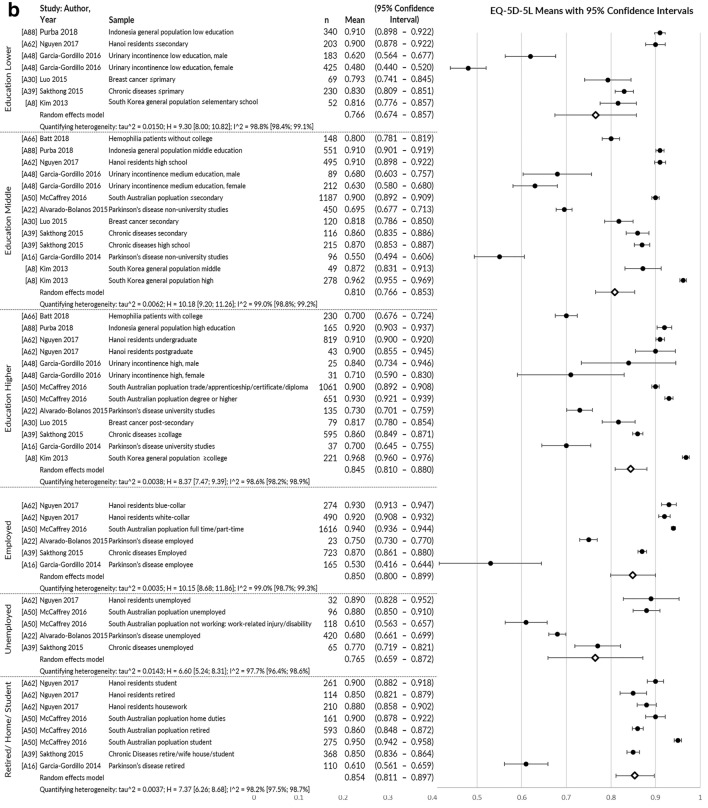

Convergent validity was assessed by the greatest number of papers (n = 33), usually examining correlations of EQ-5D-5L with other measures of health using Pearson’s correlation or Spearman’s Rho rank correlation coefficient. Figure 4a–c illustrates pooled correlations of the EQ-5D-5L index value with other measures of physical health, mental/social/cognitive health and global health. The strongest correlations were observed for multi-attribute utility instruments (pooled rho = 0.756), physical/functional measures (pooled rho = 0.582) and pain/discomfort measures (pooled rho = 0.595). The EQ-5D-5L index value correlated poorly with measures of satisfaction (pooled rho = 0.335) and cognition/communication (pooled rho = 0.259).

Fig. 4.

a Pooled correlation coefficient for EQ-5D-5L index value with other physical health measures. b Pooled correlation coefficient for EQ-5D-5L index value with other mental, emotional, cognitive and fatigue/vitality health measures. c Pooled correlation coefficient for EQ-5D-5L index value with other global health, clinical and non-health measures

On a dimension level, the strongest correlation was observed for PD and pain measures (pooled rho = 0.636), while all items correlated poorly with measures of cognition/communication and vitality/fatigue/sleep. AD was the only item to show (moderate) correlation with mental (pooled rho = 0.461), emotional and social health items (pooled rho = 0.413). Pooled correlation of EQ-5D-5L dimensions and other measures of health can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Bhadhuri et al. 2017 examined the EQ-5D-5L’s ability to measure spillover effects and found strong correlations between EQ-5D-5L scores of family of meningitis survivors and survivors’ social lives (Spearman’s Rho = 0.52, 0.45), exercise (rho = 0.55, 0.82), and personal health (rho = 0.88, 0.95) [A57]. Poor correlations were found between carers’ and survivors’ EQ-5D-5L dimensions (rho = 0.07 to 0.24), index (rho = 0.19, 0.26), and EQ-VAS (rho = 0.22, 0.24).

Table 2 includes information from studies, which examined validity other than convergent. Generally, the 5L can distinguish across disease groups, disease severity, symptoms, and related groups, and also across age and education. However, it does not consistently distinguish across groups differing with certain clinical outcomes (e.g., presence of deformities in the spine, frequency of medication use, gender, use of health services, and marital status.

Responsiveness

Fifteen studies examined whether the EQ-5D-5L captures change in health over time. All of these papers included SES and/or SRM. Although not reported, the SES could be calculated for two papers using reported information [A71, A84]. Five assessed results across respondents who improved, remained stable or deteriorated over time based on an anchor measure [A28, A39, A57, A59, A68, A87]. Four papers also reported MID [A46, A50, A71, A85]. Two used retrospective items to define change [A50, A71]. Table 4 summarizes the responsiveness results—when available, the SES and SRM are used for ease of interpretability. The EQ-5D-5L index values typically had moderate effect sizes for improved patients and those expected to improve (over the course of medical or therapeutic intervention). The largest effect sizes were observed for patients days and weeks after giving birth [A84]. Compared to other instruments, the 5L generally performs as well or better. Two additional papers addressed dimension-level changes [A23, A74], both finding the 5L to be more sensitive than the 3L. Crick et al. 2018 examined only the AD dimension and noted that both the 3L and 5L were limited in responsiveness [A74].

Discussion

The EQ-5D is a generic preference-based health status instrument that has enjoyed widespread use since its creation in the 1980s [33]. The psychometric properties of the three-level version have been well established [34–40]. Any reluctance of using the more recently developed five-level version might come in part from limited experience and evidence for validity, reliability or responsiveness in different populations [41]. This review summarized published evidence on the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L, which has been investigated in a broad array of countries, populations and contexts in the past decade. No studies found missing values to be problematic for the instrument, demonstrating feasibility. Test–retest results show potential problems with stability over time on an item level, but not at the instrument (index score) level. Note that internal consistency is not a relevant psychometric property for the EQ-5D-5L since its index score is based on a completely different measurement framework (as a preference-based measure).

Rather large proportions of respondents reporting the best health profile were observed for general population studies but less so for patient populations. The EQ-5D was conceptualized to measure deviations from full health (or negative health) and is more prone to larger ceilings than instruments that include positive health dimensions (e.g., the SF-6D). Therefore, studies with samples for which impact on the functions covered by the EQ-5D-5L (e.g., recovered cancer patients, liver disease, diabetes) is less relevant, other disease-specific instruments should be used in conjunction. On the item level, most studies, even those with populations in poorer health, reported a substantial ceiling with the dimension “self-care”, although the ceiling for self-care was low for respondents who were expected to have limitations with this function (e.g., patients before hip replacement surgery, patients shortly after cesarean section, patients with spinal cord injury [A21, A24, A84]). These results suggest that while most populations may not report problems in “self-care”, it is relevant for particular patient groups.

Our results overall solidly establish the validity of the EQ-5D-5L as supported by observed trends across subgroups (pooled means, known-group validity) as well as the convergent validity (correlation of items and index to other measures of health-related quality of life). Index values as well as the dimensions show moderate to strong correlations with physical/functional measures, pain, measures of mental and emotional health, activities of daily living and clinical/biological measures as well as with other multi-attribute utility measures. On the other hand, the 5L is not found to be correlated with satisfaction with life and cognition/communication measures. Indeed, current efforts investigating adding dimensions (so-called “bolt-ons”) to the 5L has identified cognition as an important dimension missing from the EQ-5D [42–44].

Included studies on responsiveness are heterogeneous in terms of the population, whether and which anchors were used, whether a health intervention was administered, and stratification of results across subgroups. This is not a problem unique to the EQ-5D-5L as, unlike other psychometric properties, there is not a set of recommended analyses to address responsiveness [25, 30]. Therefore, it is difficult to elucidate whether the EQ-5D-5L has problems with sensitivity to change in certain populations or with certain treatments. Despite this limitation, responsiveness is found to be acceptable by all included studies. A previous review found the EQ-5D-5L to be responsive to half of the conditions included, but found mixed evidence for the other half [26]. Responsiveness and sensitivity to changes in health is clearly an area that needs further investigation. Future studies could benefit from defining what a relevant change is for the EQ-5D-5L (MID) and defining appropriate anchor measures that can be used across populations (e.g., a level of change in EQ-VAS scores or a single self-rated health item). Parkin and colleagues (2016) demonstrated the EQ-5D-5L distribution to be affected both by the descriptive system and the value set applied [45]. Although not a focus of this study, the valuation method and applied utility scores are as important as the descriptive system when assessing responsiveness of index values. It has been shown that choice of value set has an impact on utility scores [46–49] and may change results of cost-utility analyses [48, 50, 51]. Other results show that the effect of value sets on utility scores is relatively small [A37, A83]. Due to the heterogeneity of studies found in this review, we have insufficient information to evaluate how value sets impact responsiveness. Future research will benefit from systematically examining responsiveness of the descriptive system and how choice of value set farther impacts responsiveness.

This review included nearly one hundred studies published in the past decade that investigated the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L, the majority of which sample populations from western Europe, OECD countries and secondarily, from East Asia. This clearly reflects where the EQ-5D-5L is currently used [52]. However, almost a third of new user registrations in 2018 come from countries accounting for less than 1.5% of total registrations, demonstrating widespread as opposed to concentrated use of the instrument [52]. For instance, two reviews report rapid uptake of the instrument in Eastern Europe [53, 54]. Establishing validity in other regions is crucial as the EQ-5D-5L expands in its use. Similarly, as the EQ-5D instrument has expanded in its application, it would also be important to assess how well it performs in particular settings and applications, such as used to inform clinical practice, in health services research or in health surveillance programs.

Study limitations

A limitation of this study is that studies using experimental versions of the EQ-5D-5L were excluded. Early experimental work on the content validity of the instrument [55–62] and investigations of bolt-on items [63] are therefore not captured by this review. Similarly, due to the very large number and range of quality of studies identified, we did not include application studies of the EQ-5D-5L which did not explicitly address psychometric properties, and therefore are missing distributional and perhaps responsiveness information that may have been captured by those publications. As already discussed, choice of value set and valuation methodology are as important as the descriptive system in the case of the EQ-5D. This review does not address valuation methods and therefore does not tackle a crucial component of the instrument and its index value. A previous review of valuation methodology provides valuable information on this topic [64].

Conclusions

The EQ-5D-5L is a reliable and valid generic instrument that describes health status which can be applied to a broad range of populations and settings. The assessment of responsiveness, in particular, needs further and more rigorous exploration. Rather large ceilings persist in general population samples, reflecting the conceptualization of the EQ-5D instrument, which focuses on limitations in function and symptoms, and does not include positive aspects of health such as energy or well-being.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

EuroQol Research Foundation fully funded this project (Grant ID EQ Project 2016170).

Abbreviations

- 15D

15 measure of health-related quality of life

- ADL

Activities of Daily Living

- AQoL-8D

Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D Multi-Attribute Utility Instrument

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- BREAST-Q

Breast surgery-specific patient-reported outcome measure

- DASS-21

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 Items

- DEMQOL

Dementia Quality Of Life Questionnaire

- GAD

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale

- JOABPEQ

Japanese Orthopedic Association (JOA) Back Pain Evaluation Questionnaire

- EORTC

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- EQ-VAS

Visual Analog Scale of the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)

- FIM

Functional Independence Measure

- HAL

Hemophilia Activities List

- HUI3

Health Utilities Index Mark 3

- K-BILD

King’s Brief Interstitial Lung Disease Questionnaire

- KDQoL

Kidney Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire

- MBI

Modified Barthel Index

- MDS UPDRS

Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)

- MRC

Medical Research Council scales for muscle strength

- mRS

Modified Rankin Scale

- NPI-Q

Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire

- ODI

Oswestry Disability Index

- PACT-Q2

Perception of Anticoagulant Treatment Questionnaire (PACT-Q) Part 2

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Items

- PEmb-QoL

Pulmonary Embolism Quality Of Life Questionnaire

- PGA

Patient Global Assessment

- QOLIE-31P

Quality of Life in Epilepsy-Patients-Weighted 31p

- PAS-cog

Psychogeriatric Assessment Scale-Cognitive Impairment

- QWB

Quality of Well-Being

- SF-6D

Short Form-6 Dimensions

- SF-12(v2)

Short Form-12 Items Health Survey; v2—version 2 (Subscales: BP – Bodily Pain, GH – General Health, MH – Mental Health, PF, RE – Role Emotion, RP – Role Physical, SF – social functioning, VT – Vitality, Summary Scores: MCS – Mental Component Score, PCS – Physical Component Score)

- SF-36(v2)

Short Form-36 Items Health Survey; v2—version 2 (Subscales: BP – Bodily Pain, GH – General Health, MH – Mental Health, PF, RE – Role Emotion, RP – Role Physical, SF – social functioning, VT – Vitality, Summary Scores: MCS – Mental Component Score, PCS – Physical Component Score)

- SWLS

Satisfaction with Life Scale

- WHO-5

World Health Organization-5 Well-Being Index

- WHOQoL-BREF

World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment

- WOMAC

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The submitted manuscript was not censored or directed by the foundation. The views expressed by the authors in the publication do not necessarily reflect the view of the EuroQol Group.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All four authors are members of the EuroQol group. Outside of scientific meetings, group members do not receive any financial support.

Ethical approval

This is a review paper and therefore none of the authors conducted human or animal data collection.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Works Cited

- 1.Stolk E, Ludwig K, Rand K, van Hout B, Ramos-Goni JM. Overview, update, and lessons learned from the international EQ-5D-5L valuation work: Version 2 of the EQ-5D-5L valuation Protocol. Value in Health. 2019;22(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bharmal M, Thomas J. Comparing the EQ-5D and the SF-6D descriptive systems to assess their ceiling effects in the US general population. Value in Health. 2006;9(4):262–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo N, Johnson JA, Shaw JW, Coons SJ. Relative efficiency of the EQ-5D, HUI2, and HUI3 index scores in measuring health burden of chronic medical conditions in a population health survey in the United States. Medical Care. 2009;47(1):53–60. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817d92f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palta M, Chen HY, Kaplan RM, Feeny D, Cherepanov D, Fryback DG. Standard error of measurement of 5 health utility indexes across the range of health for use in estimating reliability and responsiveness. Medical Decision Making. 2011;31(2):260–269. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10380925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tordrup D, Mossman J, Kanavos P. Responsiveness of the EQ-5D to clinical change: Is the patient experience adequately represented? International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 2014;30(1):10–19. doi: 10.1017/S0266462313000640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brazier J, Roberts J, Tsuchiya A, Busschbach J. A comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-6D across seven patient groups. Health Economics. 2004;13(9):873–884. doi: 10.1002/hec.866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunillera O, Tresserras R, Rajmil L, Vilagut G, Brugulat P, Herdman M, Mompart A, Medina A, Pardo Y, Alonso J, Brazier J, Ferrer M. Discriminative capacity of the EQ-5D, SF-6D, and SF-12 as measures of health status in population health survey. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19(6):853–864. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9639-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira LN, Ferreira PL, Pereira LN. Comparing the performance of the SF-6D and the EQ-5D in different patient groups. Acta Medica Portuguesa. 2014;27(2):236–245. doi: 10.20344/amp.4057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kontodimopoulos N, Pappa E, Chadjiapostolou Z, Arvanitaki E, Papadopoulos AA, Niakas D. Comparing the sensitivity of EQ-5D, SF-6D and 15D utilities to the specific effect of diabetic complications. The European Journal of Health Economics. 2012;13(1):111–120. doi: 10.1007/s10198-010-0290-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macran S, Weatherly H, Kind P. Measuring population health: a comparison of three generic health status measures. Medical Care. 2003;41(2):218–231. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044901.57067.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.EuroQol Research Foundation. (2019). EQ-5D-5L User Guide Version 3.0: Basic information on how to use the EQ-5D-5L instrument. https://euroqol.org/publications/user-guides.

- 12.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, Bonsel G, Badia X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Quality of Life Research. 2011;20(10):1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.EQ-5D website: EQ-5D-5L About. (2017). Retrieved 2019, from https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/.

- 14.Buchholz I, Janssen MF, Kohlmann T, Feng YS. A systematic review of studies comparing the measurement properties of the three-level and five-level versions of the EQ-5D. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(6):645–661. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0642-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schafer JL. Multiple imputation: a primer. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 1999;8(1):3–15. doi: 10.1177/096228029900800102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, van der Windt DAWM, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LA, de Vet HCW. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60(1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1973;33:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86(2):420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(4):284–290. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyo RA, Centor RM. Assessing the responsiveness of functional scales to clinical change: An analogy to diagnostic test performance. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1986;39(11):897–906. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(86)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deyo RA, Diehr P, Patrick DL. Reproducibility and responsiveness of health status measures. Statistics and strategies for evaluation. Controlled Clinical Trials. 1991;12(4 Suppl):142S–158S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(05)80019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terwee CB, Dekker FW, Wiersinga WM, Prummel MF, Bossuyt PM. On assessing responsiveness of health-related quality of life instruments: Guidelines for instrument evaluation. Quality of Life Research. 2003;12(4):349–362. doi: 10.1023/a:1023499322593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Payakachat N, Ali MM, Tilford JM. Can the EQ-5D detect meaningful change? A systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(11):1137–1154. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0295-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Revicki D, Hays RD, Cella D, Sloan J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2008;61(2):102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Revicki DA, Cella D, Hays RD, Sloan JA, Lenderking WR, Aaronson NK. Responsiveness and minimal important differences for patient reported outcomes. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4:70. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Routledge Academic; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norman GR, Sridhar FG, Guyatt GH, Walter SD. Relation of distribution- and anchor-based approaches in interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life. Medical Care. 2001;39(10):1039–1047. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. http://www.R-project.org/.

- 32.Schwarzer G. meta: An R package for meta-analysis. R News. 2007;7(3):40–45. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol group: Past, present and future. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. 2017;15(2):127–137. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finch AP, Brazier JE, Mukuria C. What is the evidence for the performance of generic preference-based measures? A systematic overview of reviews. The European Journal of Health Economics. 2018;19(4):557–570. doi: 10.1007/s10198-017-0902-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dyer MT, Goldsmith KA, Sharples LS, Buxton MJ. A review of health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Finch AP, Dritsaki M, Jommi C. Generic preference-based measures for low back pain: Which of them should be used? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41(6):E364–E374. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grobet C, Marks M, Tecklenburg L, Audige L. Application and measurement properties of EQ-5D to measure quality of life in patients with upper extremity orthopaedic disorders: A systematic literature review. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2018;138(7):953–961. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2933-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pickard AS, Wilke CT, Lin HW, Lloyd A. Health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cancer. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(5):365–384. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y, Brazier J, Longworth L. EQ-5D in skin conditions: An assessment of validity and responsiveness. The European Journal of Health Economics. 2015;16(9):927–939. doi: 10.1007/s10198-014-0638-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Janssen MF, Lubetkin EI, Sekhobo JP, Pickard AS. The use of the EQ-5D preference-based health status measure in adults with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetic Medicine. 2011;28(4):395–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Round J. Once bitten twice Shy: Thinking carefully before adopting the EQ-5D-5L. Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(6):641–643. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0636-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Y, Rowen D, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Young T, Longworth L. An exploratory study to test the impact on three “bolt-on” items to the EQ-5D. Value in Health. 2015;18(1):52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geraerds AJLM, Bonsel GJ, Janssen MF, de Jongh MA, Spronk I, Polinder S, Haagsma JA. The added value of the EQ-5D with a cognition dimension in injury patients with and without traumatic brain injury. Quality of Life Research. 2019;28(7):1931–1939. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jelsma J, Maart S. Should additional domains be added to the EQ-5D health-related quality of life instrument for community-based studies? Population Health Metrics: An analytical descriptive study; 2015. p. 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parkin D, Devlin N, Feng Y. What determines the shape of an EQ-5D index distribution? Medical Decision Making. 2016;36(8):941–951. doi: 10.1177/0272989X16645581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiadaliri AA, Eliasson B, Gerdtham UG. Does the choice of EQ-5D tariff matter? A comparison of the Swedish EQ-5D-3L index score with UK, US, Germany and Denmark among type 2 diabetes patients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13:145. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0344-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Y, Li SP, Liu L, Zhang JL, Chen G. Does the choice of tariff matter? A comparison of EQ-5D-5L utility scores using Chinese, UK, and Japanese tariffs on patients with psoriasis vulgaris in Central South China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(34):e7840. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mulhern B, Feng Y, Shah K, Janssen MF, Herdman M, van Hout B, Devlin N. Comparing the UK EQ-5D-3L and English EQ-5D-5L Value Sets (vol 36, pg 699, 2018) Pharmacoeconomics. 2018;36(6):727–727. doi: 10.1007/s40273-018-0628-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gerlinger C, Bamber L, Leverkus F, Schwenke C, Haberland C, Schmidt G, Endrikat J. Comparing the EQ-5D-5L utility index based on value sets of different countries: Impact on the interpretation of clinical study results. BMC Research Notes. 2019;12(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s13104-019-4067-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang F, Devlin N, Luo N. Cost-utility analysis using EQ-5D-5L data: Does how the utilities are derived matter? Value in Health. 2019;22(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lien K, Tam VC, Ko YJ, Mittmann N, Cheung MC, Chan KKW. Impact of country-specific EQ-5D-3L tariffs on the economic value of systemic therapies used in the treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Current Oncology. 2015;22(6):E443–E452. doi: 10.3747/co.22.2592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.EuroQol. (2018). Where is EQ-5D used? Retrieved December 03, 2019, from https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/how-can-eq-5d-be-used/where-is-eq-5d-used/.

- 53.Rencz F, Gulacsi L, Drummond M, Golicki D, Prevolnik Rupel V, Simon J, Stolk EA, Brodszky V, Baji P, Zavada J, Petrova G, Rotar A, Pentek M. EQ-5D in Central and eastern Europe: 2000-2015. Quality of Life Research. 2016;25(11):2693–2710. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1375-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zrubka Z, Rencz F, Zavada J, Golicki D, Rupel VP, Simon J, Brodszky V, Baji P, Petrova G, Rotar A, Gulacsi L, Pentek M. EQ-5D studies in musculoskeletal and connective tissue diseases in eight Central and Eastern European countries: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology International. 2017;37(12):1957–1977. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3800-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Luo N, Li M, Chevalier J, Lloyd A, Herdman M. A comparison of the scaling properties of the English, Spanish, French, and Chinese EQ-5D descriptive systems. Quality of Life Research. 2013;22(8):2237–2243. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luo N, Li M, Liu G. Investigation of Labels for a 5-level EQ-5D descriptive system in Chinese. EuroQol Proceedings. 2009;26:77–102. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luo N, Li M, Liu GG, Lloyd A, de Charro C, Herdman M. Developing the Chinese version of the new 5-level EQ-5D descriptive system: The response scaling approach. Quality of Life Research. 2013;22(4):885–890. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0200-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Luo N, Wang Y, How CH, Tay EG, Thumboo J, Herdman M. Interpretation and use of the 5-level EQ-5D response labels varied with survey language among Asians in Singapore. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2015;68(10):1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Janssen MF, Birnie E, Bonsel GJ. Quantification of the level descriptors for the standard EQ-5D three-level system and a five-level version according to two methods. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17(3):463–473. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9318-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pickard AS, De Leon MC, Kohlmann T, Cella D, Rosenbloom S. Psychometric comparison of the standard EQ-5D to a 5 level version in cancer patients. Medical Care. 2007;45(3):259–263. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254515.63841.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pickard AS, Kohlmann T, Janssen MF, Bonsel G, Rosenbloom S, Cella D. Evaluating equivalency between response systems: Application of the Rasch model to a 3-level and 5-level EQ-5D. Medical Care. 2007;45(9):812–819. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31805371aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chevalier J, De Pouvourville G. Testing a new 5 level version of the EQ-5D in France. EuroQol Proceedings. 2008;14:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Finch AP, Brazier JE, Mukuria C, Bjorner JB. An exploratory study on using principal-component analysis and confirmatory factor analysis to identify bolt-on dimensions: The EQ-5D case study. Value in Health. 2017;20(10):1362–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xie F, Gaebel K, Perampaladas K, Doble B, Pullenayegum E. Comparing EQ-5D Valuation Studies: A systematic review and methodological reporting checklist. Medical Decision Making. 2014;34(1):8–20. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13480852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References for publications included for review

- A.1.Scalone L. Comparing the standard EQ-5D-3L versus 5L version for the assessment of health of patients with live diseases. EuroQol Proceedings. 2011;16:213–239. [Google Scholar]

- A.2.Kim SH, Kim HJ, Lee SI, Jo MW. Comparing the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L in cancer patients in Korea. Quality of Life Research. 2012;21(6):1065–1073. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.3.Tran BX, Ohinmaa A, Nguyen LT. Quality of life profile and psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in HIV/AIDS patients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012;10:132. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.4.van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng YS, Kohlmann T, Busschbach J, Golicki D, Lloyd A, Scalone L, Kind P, Pickard AS. Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: Mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value. Health. 2012;15(5):708–715. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.5.Augustovski F, Rey-Ares L, Irazola V, Oppe M, Devlin NJ. Lead versus lag-time trade-off variants: Does it make any difference? The European Journal of Health Economics. 2013;14(Suppl 1):S25–S31. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0505-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.6.Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, Gudex C, Niewada M, Scalone L, Swinburn P, Busschbach J. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: A multi-country study. Quality of Life Research. 2013;22(7):1717–1727. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0322-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.7.Keeley T, Al-Janabi H, Lorgelly P, Coast J. A qualitative assessment of the content validity of the ICECAP-A and EQ-5D-5L and their appropriateness for use in health research. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e85287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.8.Kim TH, Jo MW, Lee SI, Kim SH, Chung SM. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in the general population of South Korea. Quality of Life Research. 2013;22(8):2245–2253. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.9.Lee CF, Luo N, Ng R, Wong NS, Yap YS, Lo SK, Chia WK, Yee A, Krishna L, Wong C, Goh C, Cheung YB. Comparison of the measurement properties between a short and generic instrument, the 5-level EuroQoL Group’s 5-dimension (EQ-5D-5L) questionnaire, and a longer and disease-specific instrument, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (FACT-B), in Asian breast cancer patients. Quality of Life Research. 2013;22(7):1745–1751. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.10.Scalone L, Ciampichini R, Fagiuoli S, Gardini I, Fusco F, Gaeta L, Del PA, Cesana G, Mantovani LG. Comparing the performance of the standard EQ-5D 3L with the new version EQ-5D 5L in patients with chronic hepatic diseases. Quality of Life Research. 2013;22(7):1707–1716. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0318-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.11.Swan JS, Hur C, Lee P, Motazedi T, Donelan K. Responsiveness of the testing morbidities index in colonoscopy. Value in Health. 2013;16(6):1046–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.12.Swinburn P, Lloyd A, Boye KS, Edson-Heredia E, Bowman L, Janssen B. Development of a disease-specific version of the EQ-5D-5L for use in patients suffering from psoriasis: Lessons learned from a feasibility study in the UK. Value. Health. 2013;16(8):1156–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.13.Agborsangaya CB, Lahtinen M, Cooke T, Johnson JA. Comparing the EQ-5D 3L and 5L: Measurement properties and association with chronic conditions and multimorbidity in the general population. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2014;12:74. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.14.Au N, Lorgelly PK. Anchoring vignettes for health comparisons: An analysis of response consistency. Quality of Life Research. 2014;23(6):1721–1731. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0615-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.15.Craig BM, Pickard AS, Lubetkin EI. Health problems are more common, but less severe when measured using newer EQ-5D versions. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014;67(1):93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.16.Garcia-Gordillo M, del Pozo-Cruz B, Adsuar JC, Sanchez-Martinez FI, Bellan-Perpinan JM. Validation and comparison of 15-D and EQ-5D-5L instruments in a Spanish Parkinson’s disease population sample. Quality of Life Research. 2014;23(4):1315–1326. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0569-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.17.Hinz A, Kohlmann T, Stobel-Richter Y, Zenger M, Brahler E. The quality of life questionnaire EQ-5D-5L: Psychometric properties and normative values for the general German population. Quality of Life Research. 2014;23(2):443–447. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0498-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.18.Jia YX, Cui FQ, Li L, Zhang DL, Zhang GM, Wang FZ, Gong XH, Zheng H, Wu ZH, Miao N, Sun XJ, Zhang L, Lv JJ, Yang F. Comparison between the EQ-5D-5L and the EQ-5D-3L in patients with hepatitis B. Quality of Life Research. 2014;23(8):2355–2363. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0670-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.19.Lin FJ, Pickard AS, Krishnan JA, Joo MJ, Au DH, Carson SS, Gillespie S, Henderson AG, Lindenauer PK, McBurnie MA, Mularski RA, Naureckas ET, Vollmer WM, Lee TA. Measuring health-related quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Properties of the EQ-5D-5L and PROMIS-43 short form. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.20.Mihalopoulos C, Chen G, Iezzi A, Khan MA, Richardson J. Assessing outcomes for cost-utility analysis in depression: comparison of five multi-attribute utility instruments with two depression-specific outcome measures. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;205(5):390–397. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.136036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.21.Whitehurst DG, Suryaprakash N, Engel L, Mittmann N, Noonan VK, Dvorak MF, Bryan S. Perceptions of individuals living with spinal cord injury toward preference-based quality of life instruments: A qualitative exploration. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2014;12:50. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.22.Alvarado-Bolanos A, Cervantes-Arriaga A, Rodriguez-Violante M, Llorens-Arenas R, Calderon-Fajardo H, Millan-Cepeda R, Leal-Ortega R, Estrada-Bellmann I, Zuniga-Ramirez C. Convergent validation of EQ-5D-5L in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2015;358(1–2):53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.23.Buchholz I, Thielker K, Feng YS, Kupatz P, Kohlmann T. Measuring changes in health over time using the EQ-5D 3L and 5L: A head-to-head comparison of measurement properties and sensitivity to change in a German inpatient rehabilitation sample. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24(4):829–835. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0838-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.24.Conner-Spady BL, Marshall DA, Bohm E, Dunbar MJ, Loucks L, Al KA, Noseworthy TW. Reliability and validity of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L in patients with osteoarthritis referred for hip and knee replacement. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24(7):1775–1784. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0910-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.25.Feng Y, Devlin N, Herdman M. Assessing the health of the general population in England: How do the three- and five-level versions of EQ-5D compare? Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13:171. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0356-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.26.Gamst-Klaussen T, Chen G, Lamu AN, Olsen JA. Health state utility instruments compared: inquiring into nonlinearity across EQ-5D-5L, SF-6D, HUI-3 and 15D. Quality of Life Research. 2015;25(7):1667–1678. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.27.Golicki D, Niewada M, Buczek J, Karlinska A, Kobayashi A, Janssen MF, Pickard AS. Validity of EQ-5D-5L in stroke. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24(4):845–850. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0834-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.28.Golicki D, Niewada M, Karlinska A, Buczek J, Kobayashi A, Janssen MF, Pickard AS. Comparing responsiveness of the EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-3L and EQ VAS in stroke patients. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24(6):1555–1563. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0873-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.29.Greene ME, Rader KA, Garellick G, Malchau H, Freiberg AA, Rolfson O. The EQ-5D-5L improves on the EQ-5D-3L for health-related quality-of-life assessment in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2015;473(11):3383–3390. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-4091-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.30.Luo N, Wang Y, How CH, Wong KY, Shen L, Tay EG, Thumboo J, Herdman M. Cross-cultural measurement equivalence of the EQ-5D-5L items for English-speaking Asians in Singapore. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24(6):1565–1574. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0864-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.31.Mitchell PM, Al-Janabi H, Richardson J, Iezzi A, Coast J. The relative impacts of disease on health status and capability wellbeing: A multi-country study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0143590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.32.Mulhern B, O’Gorman H, Rotherham N, Brazier J. Comparing the measurement equivalence of EQ-5D-5L across different modes of administration. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13:191. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0382-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.33.O’Leary E, Drummond FJ, Gavin A, Kinnear H, Sharp L. Psychometric evaluation of the EORTC QLQ-PR25 questionnaire in assessing health-related quality of life in prostate cancer survivors: A curate’s egg. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24(9):2219–2230. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0958-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.34.Pan CW, Sun HP, Wang X, Ma Q, Xu Y, Luo N, Wang P. The EQ-5D-5L index score is more discriminative than the EQ-5D-3L index score in diabetes patients. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24(7):1767–1774. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0902-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.35.Pattanaphesaj J, Thavorncharoensap M. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to EQ-5D-3L in the Thai diabetes patients. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13:14. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0203-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.36.Richardson J, Chen G, Khan MA, Iezzi A. Can multi-attribute utility instruments adequately account for subjective well-being? Medical Decision Making. 2015;35(3):292–304. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14567354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.37.Richardson J, Iezzi A, Khan MA. Why do multi-attribute utility instruments produce different utilities: The relative importance of the descriptive systems, scale and ‘micro-utility’ effects. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24(8):2045–2053. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0926-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.38.Richardson J, Khan MA, Iezzi A, Maxwell A. Comparing and explaining differences in the magnitude, content, and sensitivity of utilities predicted by the EQ-5D, SF-6D, HUI 3, 15D, QWB, and AQoL-8D multiattribute utility instruments. Medical Decision Making. 2015;35(3):276–291. doi: 10.1177/0272989X14543107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.39.Sakthong P, Sonsa-Ardjit N, Sukarnjanaset P, Munpan W. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in Thai patients with chronic diseases. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24(12):3015–3022. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.40.Scalone L, Cortesi PA, Ciampichini R, Cesana G, Mantovani LG. Health Related Quality of Life norm data of the general population in Italy: Results using the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L instruments. Epidemiology Biostatistics and Public Health. 2015;12(3):e11457. [Google Scholar]

- A.41.Shiroiwa T, Fukuda T, Ikeda S, Igarashi A, Noto S, Saito S, Shimozuma K. Japanese population norms for preference-based measures: Eq-5d-3 l, Eq-5d-5 l, and Sf-6d. Value. Health. 2015;18(7):A738. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1108-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.42.Wang Y, Tan NC, Tay EG, Thumboo J, Luo N. Cross-cultural measurement equivalence of the 5-level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Singapore. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2015;13:103. doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0297-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.43.White J, Withers KL, Lencioni M, Carolan-Rees G, Wilkes AR, Wood KA, Patrick H, Cunningham D, Griffith M. Cardiff cardiac ablation patient-reported outcome measure (C-CAP): validation of a new questionnaire set for patients undergoing catheter ablation for cardiac arrhythmias in the UK. Quality of Life Research. 2015;25(6):1571–1583. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]