Abstract

Purpose

Caregivers of people with cancer represent a large, overburdened, and under-recognized part of the cancer care workforce. Research efforts to address the unmet needs of these caregivers are expanding with studies focused on caregivers’ skill sets, physical and psychological health, and integration into healthcare delivery. As this field of research continues to expand, integrating caregivers’ input is vital to studies to ensure that research aligns with their experiences.

Methods

This is a focus group study of 15 cancer caregivers conducted during a cancer caregiving workshop at the University of Pittsburgh in February 2020. During the workshop, caregivers reviewed, critiqued, and proposed priorities to support caregivers of adults with cancer. We used a multistage consensus building approach to identify priority areas of research and clinical practice to address caregivers’ experiences and needs. We used descriptive content analysis to summarize caregivers’ priorities.

Results

Caregiver-identified priorities included (1) training and information about cancer and treatment, (2) caregiver integration into the patient’s healthcare delivery, (3) assistance with navigating the healthcare system, (4) focus on caregiver health and well-being, and (5) policy reform to address caregiver needs. We identified ways in which these priorities can inform cancer caregiving research and practice.

Conclusion

These recommendations should be considered by researchers, clinicians, cancer center leadership, and policymakers interested in creating caregiver-focused research protocols, interventions, and support systems.

Keywords: Behavioral science, Cancer, Family caregivers, Neoplasms, Supportive care

Background

Family caregivers are increasingly recognized as instrumental partners in the cancer healthcare experience [1–3]. While caregivers vary in their relationship to patients—spouses, partners, adult children, parents, siblings, relatives, friends, and neighbors—the work they do follows similar patterns. Cancer caregivers manage patients’ symptoms and side effects, assist with daily living skills, perform wound care, manage medications, provide emotional support and companionship, assist with transportation, and coordinate with healthcare providers and support networks [4, 5]. This work is in addition to their previous or usual roles and responsibilities which may include full- or part-time employment outside the home, caring for young children, and/or caring for other household members.

The demands that cancer caregivers undertake often lead to their distress, both of which evolve throughout the patient’s cancer experience [6, 7]. A 2018 systematic review and meta-analysis found that roughly 42 and 47% of informal cancer caregivers experience depression and anxiety, respectively [8]. Much of the caregiver experience remains unrecognized by the cancer care delivery system, though the needs of cancer caregivers are increasingly being documented and prioritized in research and clinical agendas [9].

A 2015 report by the National Alliance for Caregiving and the AARP estimated that there are over 2.8 million people in the United States providing care for someone whose primary illness is cancer. This report estimated that cancer caregivers on average spend 32.9 h a week providing care over 1.9 years. Many caregivers have to either cut down on working hours or quit working entirely due to the time needed to help care for their patients [5]. Other caregivers must continue working to maintain health insurance through their employer, especially if their patient is ensured through the caregiver’s policy. Compared with caregivers for patients with non-cancer-related illnesses, cancer caregivers are more likely to report feeling high levels of distress, with 40% reporting a need for help managing their emotional and physical stress—a finding increasingly being reported in cancer caregiving research [10, 11].

Several national organizations and researchers have recently convened groups to prioritize the research and clinical needs of cancer caregivers (Table 1). Their reports highlight the deficiencies in our current healthcare system to assess and treat caregivers while also offering guidance on the most urgent research topics. Common priority research areas identified were (a) integrating caregivers into the clinical setting, (b) assessing caregivers for distress to identify those at risk for poor health outcomes, (c) developing technology-based interventions to support caregivers in their care duties, (d) addressing the needs of diverse caregivers, and (e) prioritizing the most relevant caregiver outcomes for research. Only one of these reports included the participation of caregivers within the identification of priorities [12], while the others mainly relied on expert clinicians, researchers, and organizational leaders.

Table 1.

Summary of reports discussing caregiver priorities for research and clinical care

| Name of report or study and organization/authors | Priority area | Additional details explaining research priority provided within the report |

|---|---|---|

| Caring for caregivers and patients: research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving [14] | ||

| Organizers: National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research | ||

| Workshop participants: researchers, clinicians, advocates, and representatives from national funding agencies | ||

| Assessment of the prevalence and burden of informal cancer caregiving | • Infrastructure for comprehensive caregiver surveillance • Create risk stratification for patients and caregivers |

|

| Interventions targeting patients, caregivers, and patient-caregiver dyads | • Prioritize and define health outcomes of interest with particular measures • Evaluate the effects of tailored, interactive caregiver or dyadic interventions • Replicate potentially beneficial interventions and closely monitor intervention fidelity and dose |

|

| Caregiver integration into healthcare settings | • Develop standardized recommendations for integrating informal caregivers into clinical settings • Evaluate caregiver capacity and establish expectations for caregiver responsibilities |

|

| Maximize positive impact of technology | • Connect stakeholders to develop and test evidence-based, patient and family-centered technologies • Develop technologies to support caregiving (e.g., improved communication, monitoring, coaching, and wearable technologies) |

|

| Research priorities in family caregiving: process and outcomes of a conference on family-centered care across the trajectory of serious illness [15] | ||

| Organizers: Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation | ||

| Conference participants: researchers, policy advocates, public and private sector funding organizations, and experts in caregiving services | ||

| Evaluate technologies that facilitate choice and shared decision-making | • What is the impact of choice and shared decision-making on caregivers’ ability to provide care and their quality of life? | |

| Determine where technology is best integrated across the caregiving trajectory | • How can technologies including smart phones, security devices, and smart speakers be used to support caregivers? • What additional features should be added to these technologies to support and protect caregivers? |

|

| Evaluate interventions that are adaptive to and attuned with families’ unique situations, needs, preferences, and resources | • How do the preferences and needs of diverse families and family caregivers impact the efficacy of interventions across the caregiving trajectory? | |

| Explore caregivers’ attitudes, values, and preferences toward caregiving, services, and supports | • What assessments of caregivers can be developed, tested, and implemented? • What is the best timing and frequency of caregiver assessments of their attitudes, willingness, and readiness for the role? |

|

| Evaluate caregiver interventions attuned to real-world complexity, translation, scalability, and sustainability | • What assessments and outcomes are most meaningful in caregiver interventions? • What is the business case for caregiver interventions? |

|

| Develop a conceptual framework of caregiving for interventions | • How can a conceptual framework and typology of the caregiving experience assist in informing and guiding the development of caregiver interventions? | |

| Conduct risk and needs assessments of caregivers to understand their needs over time | • What internal and external factors influence caregiving? • What health, economic, and social factors are associated with increased risk over time among caregivers? |

|

| Conduct implementation research on caregiving interventions for diverse populations | • What are the most effective methods in adapting evidence-based interventions for diverse populations? • What are the best strategies for identifying adaptation to interventions for diverse populations? |

|

| Develop outcome measures that are relevant to caregivers from diverse social and cultural groups | • How do we know that an intervention worked from the perspective of diverse caregivers? • What is considered a meaningful outcome from the perspective of diverse caregivers? |

|

| Develop research methodologies that account for the complex structures of family caregiving | • How do different family structures affect outcomes? • How do caregivers from complex structures communicate healthcare information to each other? |

|

| Priorities for caregiver research in cancer care: an international Delphi survey of caregivers, clinicians, managers, and researchers [8] | ||

| Sylvie D. Lambert et al. | ||

| Study sample: researchers, clinicians, managers, and caregivers | ||

| Home care interventions | No recommendations provided | |

| Caregiver perspectives on how support and information can best be provided to them by healthcare professionals | ||

| Screening to identify caregivers at greatest risk of burden | ||

| Financial impact of “burnout” for caregivers and society | ||

| Impacts of financial demands on caregivers | ||

| Direct costs of caregiving for caregivers | ||

| Characteristics of caregivers at high-risk of burden or burnout | ||

| Training for healthcare professionals working with caregivers | ||

| Resources and support for caregivers about death and dying | ||

This study addresses the lack of caregiver-identified priorities to address the challenges and unmet needs of cancer caregivers. Research that is based on the perspectives of stakeholders is thought to yield results that are more relevant and meaningfUl to the target population [13]. Research and clinical programs that proactively engage caregiver stakeholders can help ensure that initiatives align with caregivers’ interests and needs. We convened a group of caregivers of adult cancer patients to learn more about their perceptions of research priorities and to develop group consensus about the direction of cancer caregiving research. The purpose of this report is to summarize caregivers’ recommendations for research and clinical priorities in cancer caregiving.

Methods

The research team organized the Inaugural Cancer and Caregiving Research Conference and Caregiver Workshop held at the University of Pittsburgh. The first day was a research conference in which a national group of leading cancer caregiving researchers presented their work and identified research priorities. The second day’s workshop convened caregivers and community advocates to review, critique, and propose priorities for cancer caregiving research. Leaders of local advocacy organizations attended the workshop to provide information and resources to caregivers. Most caregivers who participated in the workshop did not attend the research conference.

We recruited informal, adult caregivers of patients with cancer to participate in the Caregiver Workshop. These were our only inclusion criteria; we did not specify the patient’s current status (e.g., receiving treatment, in survivorship, time since diagnosis, etc.) but primarily targeted our recruitment toward caregivers supporting patients actively receiving treatment. We used multiple channels to recruit caregivers. We shared posters and informational brochures with the area’s National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center clinicians, principal investigators of NIH-funded caregiver research studies, community organizations, and advocacy groups who serve cancer caregivers. We also called caregivers known to the Family Caregiver Advocacy, Research, and Education (CARE) Center within the Gynecologic Oncology Clinic. Finally, we circulated social media announcements about the workshop. We received human subjects’ approval for this study from the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board before the commencement of the conference.

At the beginning of the workshop, we introduced caregivers to the purpose and procedures of developing caregiver-identified research priorities. Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire capturing their characteristics and relationship to their patients with cancer. We interspersed selfcare activities during the workshop to teach caregivers accessible ways of reducing their stress including meditation, aromatherapy, and sitting yoga demonstrations.

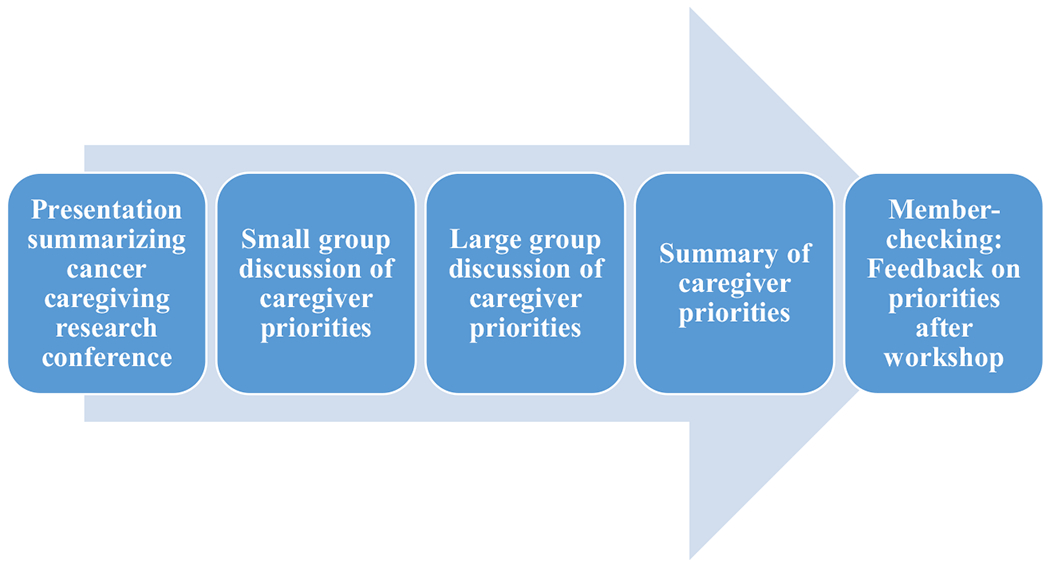

We conducted a focus group study using a multistage consensus building approach to define cancer caregivers’ priorities (Fig. 1) [14]. We selected this methodology because we aimed to uncover the unique experiences, beliefs, and values of cancer caregivers in a way that allowed for caregivers to interact and co-create a list of priorities [15]. Our goal was to develop meaningful group agreement on how cancer caregivers’ top concerns could be addressed by researchers and clinicians. The multistep process is detailed in the following sections and involved sharing the research priorities presented during the previous day’s research conference, followed by small-group discussion (4–5 caregivers), full-group discussion, determination of a summary of a key set of priorities, and stakeholder verification of priorities after the workshop. We used a conversational approach to assessing caregivers’ priorities because it allowed participants to share their experiences openly, as many were unaccustomed to discussing their needs. Moderators, who had participated in two training sessions regarding the focus group protocol, facilitated the focus group discussions by asking the group broad questions, clarifying responses, and documenting group ideas. We did not audio-record focus group discussions to (a) ensure caregivers felt comfortable sharing their experiences and (b) encourage participants to contribute toward the overall goal of a mutually agreed upon set of priorities rather than individual viewpoints. Scribes sat with each group of cancer caregivers and moderators and took detailed notes that were later used for analyses.

Fig. 1.

Steps taken to build consensus of cancer caregiving priorities

First, the workshop organizers shared a summary of the research presented during the first day of the conference. We strongly cautioned that, while these findings represented the latest research in cancer caregiving, they did not necessarily reflect the needs of cancer caregivers, underscoring our desire to discuss their priorities during the workshop. In the second step (45 min), caregivers worked in small groups of round tables with a moderator to discuss and critique priorities in cancer caregiving relative to caregivers’ personal experiences. Caregivers were encouraged to brainstorm freely without any limitations to the types of priorities. Moderators encouraged more reticent participants to share their ideas by requesting their input. This also served as a way to ensure group agreement regarding priorities. In the third step (45 min), the small groups reported their ideas to the larger group and collectively discussed common and divergent ideas. In the fourth step (30 min), the large group worked together to finalize a set of key research and clinical priorities to support cancer caregivers. This final step forced caregivers to explicitly list a final set of priorities that they most wanted to have addressed. As caregivers shared the most consistent priorities, moderators wrote them on large writing boards in the front of the room. Moderators asked caregivers to reflect on the final set of priorities to ensure they adequately captured their needs and no ideas were left out. Caregivers reported agreeing with the final set of priorities.

We used a descriptive content analysis approach to summarize and categorize participants’ priorities [16]. After the workshop, we first reviewed the notes from the large-group discussion and then corroborated them with notes from the small-group discussions to ensure that the final list of priorities reflected the majority of discussions and no major ideas were missed. To ensure transparency in our data analysis process, we maintained an audit trail describing our steps reviewing, summarizing, and synthesizing the qualitative data. Our goal was to organize the information caregivers shared during the workshop by creating categories that encompassed similar ideas. We attempted to limit our transformation of the data, opting to stay close to the words and meaning caregivers provided during the workshop, thus limiting the interpretation of the words they used [17]. The first author (T.T.) labeled these categories as topic areas of caregivers’ priority unmet needs. This set of priorities was shared with co-authors (including all moderators) for critique based on their experience during the workshop, resulting in a final set of themes.

After the conference, we conducted member-checking to ensure that the final priorities resonated with all workshop caregivers [18]. This was accomplished by sharing our summary of caregiver-identified priorities with all participants and requesting their feedback. Caregivers could indicate support of the final list and/or modify the final priorities to reflect their own experiences. This also served as a way for any caregivers who were more reserved during the focus group to share any differing opinions. We integrated caregivers’ suggestions, which were minor, to yield the final set of consensus priorities and confirmed that no new ideas were generated.

Results

The Cancer Caregiver Workshop was held on February 14, 2020, in a private event space on the University of Pittsburgh campus. Participants included fifteen cancer caregivers caring for an adult with cancer. Table 2 reports the demographic characteristics of the caregiver participants. Seven members of local advocacy organizations also attended and joined in the group discussions. Six caregivers who had registered were unable to attend due to last-minute conflicts. Of the caregivers who did not attend, three were parents of young adults with cancer, one was the daughter of a woman with cancer, and two were husbands of women with cancer. Participants ranged in age from 41 to 79 years old (65 ± 10 years). They reported a range of income and educational levels, though all participants were White and non-Hispanic. One participant was supporting a parent who did not live with them; all other participants were supporting a spouse who lived with them. On average, participants reported providing care for 24 ± 34 months and 8 ± 7 h a day. Eight participants reported being retired, unemployed, or disabled; seven reported working either full-time, part-time, or as a homemaker.

Table 2.

Cancer caregiver demographic characteristics (N = 15)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age M (SD) | 65 (10) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 7 (47) |

| Female | 8 (53) |

| Race | |

| White | 15 (100) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 15 (100) |

| Education | |

| High school degree or GED or less | 3 (20) |

| Associate’s degree | 1 (7) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 5 (33) |

| Master’s degree | 4 (27) |

| Professional degree (JD, MD, PhD) | 2 (13) |

| Annual household income | |

| $20–40k | 2 (13) |

| $40–60k | 5 (33) |

| $60–80k | 2 (13) |

| $80–100k | 1 (7) |

| > $150k | 5 (33) |

| Relationship to patient | |

| Spouse/partner | 14 (93) |

| Adult child | 1 (7) |

| Living with patient | 14 (93) |

| Employment status | |

| Retired | 5 (33) |

| Working full-time | 1 (7) |

| Working part-time | 5 (33) |

| Full-time homemaker | 1 (7) |

| Unemployed | 2 (13) |

| Disabled | 1 (7) |

| Months spent as caregiver M (SD) | 23.7 (34) |

| Average hours per day providing care M (SD) | 7.6 (7.0) |

| Patient cancer type | |

| Endometrial | 4 (27) |

| Lymphoma | 3 (20) |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 2 (13) |

| Esophageal | 1 (7) |

| Laryngeal | 1 (7) |

| Melanoma | 1 (7) |

| Pancreatic | 1 (7) |

| Not disclosed | 2 (13) |

Caregiver-identified priorities fell within five main topic areas: (a) information and training about cancer and treatment, (b) caregiver integration into the patient’s healthcare delivery, (c) assistance with navigating the healthcare system, (d) a focus on caregiver health and well-being, and (e) policy reform to address caregivers’ unmet needs. Table 3 summarizes each priority along with specific comments provided by participants during the workshop.

Table 3.

Cancer caregiver recommendations of priorities in caregiver research

| Topic | Priority | Key examples of a priority (when expressed by caregivers)a |

|---|---|---|

| Training and information about cancer and treatment | ||

| Share diagnosis, treatment, and medical information with caregiver | • Include caregiver in discussions of diagnosis and treatment decisions with the patients’ permission • Recommend Internet websites and cancer center resources with reliable information • Provide basic information about lab results in writing • Provide tailored information about integrative and complementary treatments including interactions with cancer treatments in writing • Evaluate the applicability of “promising” advertisements for treatments/centers |

|

| Teach skills for caring for loved one when patient is discharged to home | • Teach how to properly assist walking, moving in bed, managing side effects • Provide ongoing support to the caregiver once patient is at home |

|

| Offer a “caregiver boot camp” to train caregivers on their new role and what to expect | ||

| Caregiver integration into the patient’s healthcare delivery | ||

| Clarify caregiver(s) and patient relationships | • Identify total network of people • Verify caregivers’ location relative to the patient |

|

| Approach patient and caregiver as a unit | • Include caregiver concerns as a part of the agenda • Ensure that the caregivers’ concerns are acknowledged and discussed independent of the patient |

|

| Include caregiver assessments of patient into clinical discussions | • Ensure that the caregiver is respected and acknowledged as a key member of the team by healthcare providers who may hesitate to include caregiver due to patient privacy concerns • Allow disclosure of information to caregivers based on caregiver and/or patient preference |

|

| Build caregiver alliance with healthcare team, especially doctor and nurse | • Accommodate caregivers who provide care from a distance (e.g., using teleconferencing during patient appointments) | |

| Inclusion in the medical record | • Include the caregiver in the medical record of the patient including name, relationship to patient, pertinent information • Provide a record of information that has been shared with caregiver (e.g., caregiver discharge summary, checklist of caregiver tasks) |

|

| Provide caregivers with a report at the end of a visit | • Provide a summary after clinic visits including “to do,” “to remember,” and “to communicate” | |

| Assistance with navigating the healthcare system | ||

| Offer an orientation to the cancer center, how the center works, general expectations, and key contacts | • Provide names, phone numbers, and emails of people to contact tailored to the patients care | |

| Provide a point-person at cancer center to contact with questions | • Check in with caregiver soon after starting treatment to review main points of contact | |

| Clarify the process and expectations for reaching out | • Provide a description of individual roles within healthcare team • Clarify who to call with questions and when • Clarify points at which caregiver should contact healthcare team (e.g., specific symptoms and side effects of cancer and treatment) |

|

| Provide physical space and resources within the cancer center | • Provide a safe space for expressing emotions, a “crying room” • Create a lending library of resources • Facilitate opportunities to engage in resources and activities at the cancer center |

|

| Assistance with understanding insurance claims and financial resources | • Identify efficient and cost-effective ways to access and purchase medications | |

| Focus on caregiver health and well-being | ||

| Respite care including short-notice relief | ||

| Release valve from stress | ||

| Caregivers becoming advocates for themselves | ||

| Caregiving mentoring and peer matching programs | ||

| Policy reform to address caregivers | ||

| Identify and implement models of healthcare that include caregiving | • Develop best practices of integrating caregivers into the healthcare system • Examine patient and caregiver outcomes between countries with “universal” healthcare and those without |

|

| Including the caregiver within medical, nursing, and health-related school curricula | ||

Empty cells indicate that caregiver participants did not discuss specific examples of a topic

Information and training about cancer and treatment

Participants reported wanting more effective mechanisms to receive clear, up-to-date information about the patient’s cancer diagnosis and treatment. Their primary interest was in receiving vetted, trustworthy information about the diagnosis and treatment, but they also noted needing information on a range of issues related to the patient’s cancer. These concerns included information to help interpret lab results, differentiate between urgent symptoms requiring immediate medical care versus non-urgent symptoms and side effects, and assess the potential applicability of integrative and complementary therapies in the patient’s care. Participants also wanted help in determining if advertisements (e.g., television commercials) for promising cancer treatments are applicable to their patient so that they could better cope with the disappointment of realizing that an advertised treatment may not apply to the patient. Additionally, caregivers identified the time after hospital discharge as a particularly intensive and anxiety-provoking period when they lacked adequate information and training to meet the demands of patient care. Given their high informational needs, participants suggested that cancer centers organize “caregiver boot camps” in which information and training could be provided in an intensive, condensed format at the beginning of the cancer experience.

Caregiver integration into the patient’s healthcare delivery

Participants called for a change in practice to ensure that caregivers are actively engaged in the patient’s clinical care. They discussed experiences in which they felt dismissed and forgotten by clinicians during clinic visits. This occurred despite the caregiver having useful and intimate knowledge of the patient’s status and needing to understand how to support the patient based on the plan discussed during the clinic visit. First, participants needed clinicians to ask questions that would allow the clinician to understand the unique aspects of the caregiver/patient relationship. They wanted clinicians to approach the caregiver and patient as a single unit, allowing caregivers to enter the conversation and provide assessments of the patient’s health. Participants described a strong desire to feel an alliance with the entire healthcare team, especially when the caregiver lived separately from the patient. Participants consistently reported a need for caregivers to be given access to the patient’s medical record with a list of information that had been shared with them. Finally, participants wanted to be given a very specific “to do” list at the end of each clinic visit as a method for improving communication and prioritization of caregiving tasks.

Assistance with navigating the healthcare system

Participants repeatedly mentioned needing support to navigate the fragmented healthcare system. They suggested offering caregivers an orientation to the cancer center to familiarize them with how the center works, expectations of patients and caregivers, and explicit persons and points of contact. Participants wanted to have a single point of contact at the cancer center but also wanted to know the process for reaching out to the cancer center and to whom they should address specific questions. Having physical spaces within the cancer center designated for caregivers was another priority mentioned by participants, such as a lending library or activities specifically designed for caregivers (e.g., books, videos, stress reduction activities). Another need related to navigation was around managing the financial aspects of cancer care including understanding insurance policies and claims and finding cost-effective ways of purchasing medications.

Focus on caregiver health and well-being

Participants shared a need for addressing their health concerns. Longer-term caregivers or those providing more intense care reported being desperate for respite care to allow them personal time to attend to their own needs, including when such care is needed with short notice. Several caregivers expended a great deal of time searching, often without success, for available and affordable respite care. Participants described needing a way to release the mounting stress they felt and often experienced the need to conceal this stress from the patient. One participant indicated that a “crying room” would help her release her distress away from her loved one in a private space. Recognizing the volume and complexity of challenges they experience, participants wanted to learn how to advocate for themselves within the cancer healthcare system and more broadly within their social environments. Some suggested creating peer-mentoring or matching programs to allow caregivers to support each other.

Policy reform to address caregivers

Participants were attuned to the broader sociocultural factors impacting their experience as cancer caregivers and pointed to ways in which policy reform could address their needs. They recommended that policymakers examine patient and caregiver outcomes between countries with different healthcare models to identify and implement models of healthcare that expressly include caregivers to improve outcomes. Recognizing the need for clinicians to be educated in the psychosocial aspects of family caregiving, participants wanted medical, nursing, and other health-related fields to develop and integrate a family caregiving curriculum into their training programs.

Based on the topics and priorities shared by caregiver participants during the Cancer Caregiver Workshop, we propose several possible research and quality improvement questions (Table 4). Addressing these questions through rigorous, caregiver-oriented scholarship can begin to mend the current lack of caregiver support and integration in cancer care. While not comprehensive, these questions are intended to stimulate researchers and clinicians wishing to translate caregivers’ stated priorities into impactful, responsive programs of research and practice.

Table 4.

Research questions by caregiver-identified topic

| Topic | Potential research questions |

|---|---|

| Training and information about cancer and treatment | • What modes of delivering health information (text, video, online, or paper) to caregivers work best and for whom? • How should caregiver educational and training interventions be designed to provide caregivers with timely, efficient health information and caregiving skills? • How is health information between caregivers, healthcare providers, and patients shared, and how does this impact caregiver and patient decision-making and outcomes? |

| Caregiver integration into the patient’s healthcare delivery | • How can clinicians and healthcare systems integrate various caregiver structures into the cancer care (e.g., number of caregivers, location relative to the patient, etc.)? • How does the caregiver perspective shape clinical care, and how can clinicians’ communication styles elicit and include caregivers within assessment and decision-making? • How can the medical record be used as a platform for incorporating caregivers into the health information delivery and decision-making? |

| Assistance with navigating the healthcare system | • How do caregivers access people and resources within the cancer care delivery system and how can this be more efficient? • What barriers prevent caregivers from being able to effectively navigate the healthcare system, and how can these barriers be overcome through innovative interventions? |

| Focus on caregiver health and well-being | • What interventions reduce caregiver distress and how does this impact the experience and health impacts of caregiving? • Do peer mentors improve caregivers’ unmet needs and reduce their distress? If so, how can such programs be designed to be scalable and replicable? |

| Policy reform to address caregivers | • What models of care successfully integrate caregivers into clinical care and what impact does this have on caregivers and patients? • To what extent do health-related training programs currently include caregivers within their curricula, and what content can be added to provide them with adequate training on the role of caregivers? |

Discussion

This study provides insights into how cancer caregivers can facilitate the prioritization of research questions and clinical care to address their needs. Caregivers’ priorities centered on the barriers they encounter while trying to support someone with a cancer diagnosis and undergoing treatment. For each overarching topic, caregivers shared multiple priorities that often included tangible examples of how they could be better equipped to be a supportive, informed, capable caregiver.

Major themes included needing (a) information and training on cancer diagnosis and treatment, (b) recognition from clinicians and inclusion within the medical setting, and (c) assistance with understanding how the cancer clinic functions so that they can effectively navigate the cancer care delivery system. These three themes underscore how current cancer care delivery systems are not designed to include caregivers’ critical involvement in the patients’ care and decision-making with regard to treatment. Although caregivers interact with clinicians and perform many essential duties, caregivers reported feeling unprepared to support their patient. Caregivers desired increased acknowledgment, information, and support within the cancer care delivery system so that they can competently complete their caregiver responsibilities.

While caregiver well-being was included as an additional major theme—including providing respite care, peermentoring, and self-advocacy—caregivers did not expand on additional ways in which their well-being could be addressed. Rather, they primarily focused their priorities on improving their role in supporting someone with cancer. Finally, caregivers shared a major theme of policy-level concerns impacting caregiving, pointing to more systematic ways to support cancer caregivers. They wanted to investigate existing models for including caregivers within the healthcare system and see if those models could be used within the cancer care delivery system. They also saw value in providing education within health professional schools so that they are trained in the role and importance of the caregiver before becoming a clinician.

The caregiver-identified priorities established during this workshop reflect many of the priority areas documented in the recent publications in Table 1. Mainly, our results corroborate consistent calls by the research community for caregivers to be integrated into cancer care delivery [12, 19, 20]. Caregivers’ stated preferences for more practical information and training support recent studies evaluating interventions to train caregivers in skills necessary to support the patient and themselves including, but not limited to, the post-discharge period [21–23]. The results also reinforce pressing calls for evidence-based models of care that reorient the cancer delivery system to include caregivers throughout all aspects of clinical care [24, 25]. Caregivers wanted access to patients’ medical records and inclusion within discussions with clinicians, which require redesigning provider training, clinical encounters, patient privacy, and medical records to support caregiver inclusion. Finally, caregiver-identified priorities in the workshop demonstrate a need to focus on the financial impact of cancer caregiving as caregivers reported unmet needs managing finances and finding affordable medications [26].

The fact that caregivers identified priorities that largely echo previously published priorities for cancer caregivers is both validating and a call to action for the cancer community. While the consistency across priorities demonstrates that they are uniformly recognized as the most critical to address, it also underscores that previous attempts to address these needs have not been successful. The added weight of having caregiver stakeholders independently share these priorities should further activate the cancer community in addressing these priorities. Notably, since caregivers in this focus group mostly cared for individuals with rarer types of cancer, this suggests that addressing caregivers’ priorities may have widespread impact.

Several differences existed between priorities caregivers mentioned in this workshop and those from the recent publications in Table 1. Caregivers in our workshop did not have their own physical and mental health as the focus of their research and clinical priorities. While they suggested ways in which their personal needs could be addressed, most of their priorities focused on bolstering their caregiving skills. This could be a result of gender differences in discussing personal needs given that half of our sample was male [27, 28], social desirability biases since some patients attended the workshop, as well as having fewer caregivers further out from their patient’s cancer treatment when caregivers frequently begin to focus more on their own needs [29].

Additionally, caregivers’ technology priorities focused on access to and use of the patient’s medical record. Their needs did not focus on how technology could monitor their health or workload. Even though caregivers did not spontaneously suggest technology-based interventions, if these interventions were designed to address caregivers’ priority needs in an inclusive, tailored fashion, then caregivers may find these interventions feasible and acceptable [30]. For example, caregivers may endorse the use of technology to facilitate a “caregiver boot camp” if doing so would make the boot camp widely accessible and would permit flexible attendance (e.g., teleconferencing that caregivers could attend at home synchronously or asynchronously). While participants mentioned the need to support caregivers providing care remotely, they did not mention the need for research addressing the needs of diverse caregivers, likely due to the homogeneity of our sample, which remains a limitation of cancer caregiver research [3].

These results magnify recently published suggestions for conducting cancer caregiver interventions. For example, a 2015 meeting held by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Nursing Research identified common caregiver outcomes in research studies to include quality of life, mastery, burden, preparedness, self-efficacy, distress, and strain, among other outcomes [19]. Aspects of all of these outcomes were endorsed by caregivers in our workshop, suggesting that these outcomes may be meaningful intervention targets for cancer caregivers. Additionally, researchers may benefit from collaborating with caregiver stakeholders throughout the design and implementation of interventions to ensure their interventions are specifically tailored to caregiver needs and preferences.

The results of this workshop can assist researchers in designing and implementing cancer caregiving interventions. A recent systematic review of psychosocial interventions for cancer caregivers have found limited immediate or longterm benefits of interventions on caregiver depression, anxiety, distress, or quality of life [31]. At the same time, systematic reviews have critiqued cancer caregiver interventions for rarely including input from caregiver stakeholders or assessing caregiver satisfaction with interventions [31, 32], potentially limiting the ability of interventions to be acceptable to caregivers and tailored to their perspective. While participants in the workshop were not prompted to nor did they independently discuss the implications of specific intervention designs or caregiver-reported outcome measures pertinent to them, we suggest specific ways in which researchers can translate caregiver-identified needs and concerns into relevant and meaningful studies (Table 3).

More expediently, these findings point to ways in which caregivers can receive support for and validation of their priorities within the clinical setting. First, caregivers can receive specific training about their patient’s cancer diagnosis, treatment, and medical needs. This could be included within regular treatment planning conversations and discharge instructions [33, 34]. Second, healthcare providers can acknowledge and include caregivers within clinical visits. This requires communication and skills training in how to effectively integrate caregivers into patient care, including documenting caregiver needs and concerns within the medical record [35, 36]. Finally, cancer centers can provide explicit details regarding navigating the cancer center, understanding individuals’ roles within the center, and recognizing who to contact with specific questions.

A limitation of these workshop-generated priorities is the small, homogeneous sample of caregivers present at the workshop. We aimed to include caregivers currently supporting someone with cancer, which is an extremely challenging demographic to recruit for a full-day event. Our research team advertised the workshop throughout the broad Pittsburgh area using clinical, research, and community partners and individually called caregivers to encourage them to attend. We provided two meals and reduced parking and hotel costs in addition to the events of the workshop. Despite these efforts, registering caregivers to attend the workshop was extremely difficult. Those who were able to participate were invested and passionate about their involvement. Several caregivers cited reasons for not being able to attend including the inability to leave the patient due to lack of respite care, limited free time, time of year (February) and weather concerns, work and childcare obligations, and driving distance as many lived more than 1 h away. Researchers wishing to include caregivers as stakeholders in their research programs should strategize ways to reduce caregivers’ barriers to inclusion. Organizers should identify additional strategies to support the participation by caregivers from diverse family structures, age groups, socioeconomic backgrounds, and racial and ethnic minorities. These caregivers may have needs that will expand the current list of priorities and ensure their broad applicability. Moreover, our analysis included established methods for ensuring the trustworthiness of qualitative data analysis (e.g., member-checking, creation of an audit trail, and thick description of our results). Future qualitative research can employ additional techniques to establish the rigor of the analysis and results such as those proposed by Lincoln and Guba [37].

Future work incorporating caregivers as research stakeholders should consider the unique challenges in conducting a similar type of workshop. Our workshop’s goal of creating consensus research priorities may have been too ambitious within the time frame, given that most caregivers were supporting a patient currently receiving treatment. Our workshop ran from 8 am to 3 pm, and most participants indicated that this was an appropriate amount of time. During the rounds of discussion, caregivers enjoyed sharing their personal experiences with other caregivers, and they cited this as a major reason for attending the workshop in a brief survey evaluating the workshop. Many caregivers experienced real-time caregiving emergencies during the workshop that required them to briefly leave the focus group. Future work attempting to include caregivers as stakeholders should address caregivers’ need for connection, support, and flexibility in addition to building capacity to partner with research projects. For example, caregiver meetings could meet via teleconferencing and on weekends when they are more likely to have flexibility.

Conclusion

Cancer caregivers are a heavily burdened group whom the cancer care delivery system depends on for providing physical, emotional, and practical support to patients with cancer. Understanding their priorities can help researchers and clinicians design studies that are responsive to their needs. The results of our Cancer Caregiver Workshop, while limited in scope, reflect calls within the research community for studies that address caregiver integration into healthcare delivery, provision of information and training, and assistance navigating the healthcare system. Caregivers also prioritized interventions focused on reducing their distress as well as making policy-level changes to improve the experience of cancer caregivers. These recommendations, if implemented by researchers, clinicians, cancer care leadership, and policymakers, may reduce the stress and distress associated with caregiving. Future work addressing cancer caregivers’ needs should be responsive to these needs and elicit additional stakeholder insights into how research can improve their health and well-being.

Acknowledgments

Funding (Donovan) The contents of this manuscript were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90RTGE0002-01-00). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this manuscript do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

(Donovan) Health Policy Institute, University of Pittsburgh

(Thomas) American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant MSRG-18-051-51

(Thomas) National Palliative Care Research Center Career Development Award

(UPMC Hillman Cancer Center) P30CA047904

Footnotes

Data availability Data is available upon request.

Conflict of interest The authors have no conflicts of interest or competing interests to report.

Ethics approval This study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (STUDY20010122).

Consent to participate All participants provided consent to participate in this research study before participating.

Consent for publication Not applicable.

Code availability Not applicable.

References

- 1.Northouse L, Williams A-L, Given B, Mccorkle R (2012) Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 30:1227–1234. 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Given BA, Given CW, Sherwood P (2012) The challenge of quality cancer care for family caregivers. Semin Oncol Nurs 28:205–212. 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrell B, Wittenberg E (2017) A review of family caregiving intervention trials in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin 67:318–325. 10.3322/caac.21396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K et al. (2011) Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: a hidden quality issue? Psychooncology 20:44–52. 10.1002/pon.1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt GG, Longacre ML, Kent EE, Weber-Raley L (2016) Cancer caregiving in the U.S. An intense, episodic, and challenging care experience. In: National Alliance for Caregiving, vol 2016, p 34 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butow PN, Price MA, Bell ML, Webb PM, deFazio A, The Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group, The Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Quality of Life Study Investigators, Friedlander M (2014) Caring for women with ovarian cancer in the last year of life: a longitudinal study of caregiver quality of life, distress and unmet needs. Gynecol Oncol 132:690–697. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hudson PL, Thomas K, Trauer T, Remedios C, Clarke D (2011) Psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manag 41:522–534. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mei GH, Mei CD, Yang F et al. (2018) Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med (United States):97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz R, Eden J (eds) (2016) Families caring for an aging America. National Academies Press, Washington, DC: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowman KF, Rose JH, Radziewicz RM, O’Toole EE, Berila RA (2009) Family caregiver engagement in a coping and communication support intervention tailored to advanced cancer patients and families. Cancer Nurs 32:73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Public Policy Institute A (2014) Caregiving in the U.S. 2015 Report Acknowledgments [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lambert SD, Ould Brahim L, Morrison M, Girgis A, Yaffe M, Belzile E, Clayberg K, Robinson J, Thorne S, Bottorff JL, Duggleby W, Campbell-Enns H, Kim Y, Loiselle CG (2019) Priorities for caregiver research in cancer care: an international Delphi survey of caregivers, clinicians, managers, and researchers. Support Care Cancer 27:805–817. 10.1007/s00520-018-4314-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, Herron-Marx S, Hughes J, Tysall C, Suleman R (2014) Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect 17:637–650. 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown BB (1968) Delphi process: a methodology used for the elicitation of opinions of experts | RAND [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH (2009) Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation 119:1442–1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elo S, Kyngäs H (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 62:107–115. 10.1m/jT365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandelowski M, Leeman J (2012) Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qual Health Res 22:1404–1413. 10.1177/1049732312450368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey L (2015) Beyond member-checking: a dialogic approach to the research interview. Int J Res Method Educ 38:23–38. 10.1080/1743727X.2014.914487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, Litzelman K, Chou WYS, Shelburne N, Timura C, O’Mara A, Huss K (2016) Caring for caregivers and patients: research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer 122:1987–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvath TA, Mongoven JM, Bidwell JT, Cothran FA, Sexson KE, Mason DJ, Buckwalter K (2020) Research priorities in family caregiving: process and outcomes of a conference on family-centered care across the trajectory of serious illness. Gerontologist 60:S5–S13. 10.1093/geront/gnz138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hendrix CC, Bailey DE, Steinhauser KE et al. (2016) Effects of enhanced caregiver training program on cancer caregiver’s self-efficacy, preparedness, and psychological well-being. Support Care Cancer 24:327–336. 10.1007/s00520-015-2797-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DuBenske LL, Gustafson DH, Namkoong K et al. (2014) CHESS improves cancer caregivers’ burden and mood: results of an eHealth RCT. Health Psychol 33:1261–1272. 10.1037/a0034216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Tosteson T, Li Z, Li Z, Frost J, Dragnev KH, Akyar I, Hegel MT, Bakitas MA (2015) Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33: 1446–1452. 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.7824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry LL, Dalwadi SM, Jacobson JO (2017) Supporting the supporters: what family caregivers need to care for a loved one with cancer. J Oncol Pract 13:35–41. 10.1200/jop.2016.017913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alfano CM, Leach CR, Smith TG et al. (2019) Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: a blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin 69:35–49. 10.3322/CAAC.21548@10.3322/(ISSN)1542-4863.ACS_CANCER_CONTROL_BLUEPRINTS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley CJ (2019) Economic burden associated with cancer caregiving. Semin Oncol Nurs 35:333–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez V, Copp G, Molassiotis A (2012) Male caregivers of patients with breast and gynecologic cancer. Cancer Nurs 35:402–410. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318231daf0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthews AB (2003) Role and gender differences in cancer-related distress: a comparison of survivor and caregiver self-reports. Oncol Nurs Forum 30:493–499. 10.1188/03.ONF.493-499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Girgis A, Lambert SD, McElduff P, Bonevski B, Lecathelinais C, Boyes A, Stacey F (2013) Some things change, some things stay the same: a longitudinal analysis of cancer caregivers’ unmet supportive care needs. Psychooncology 22:1557–1564. 10.1002/pon.3166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heynsbergh N, Heckel L, Botti M, Livingston PM (2018) Feasibility, usability and acceptability of technology-based interventions for informal cancer carers: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 18:244. 10.1186/s12885-018-4160-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Treanor CJ, Santin O, Prue G, Coleman H, Cardwell CR, O’Halloran P, Donnelly M, Cochrane Consumers and Communication Group (2019) Psychosocial interventions for informal caregivers of people living with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019. 10.1002/14651858.CD009912.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ugalde A, Gaskin CJ, Rankin NM, Schofield P, Boltong A, Aranda S, Chambers S, Krishnasamy M, Livingston PM (2019) A systematic review of cancer caregiver interventions: appraising the potential for implementation of evidence into practice. Psychooncology 28:687–701. 10.1002/pon.5018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longacre ML, Weber-Raley L, Kent EE (2020) Toward engaging caregivers: inclusion in care and receipt of information and training among caregivers for cancer patients who have been hospitalized. 10.1007/s13187-019-01673-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jivraj N, Ould Gallagher L, Papadakos J, Abdelmutti N, Trang A, Ferguson SE (2018) Empowering patients and caregivers with knowledge: the development of a nurse-led gynecologic oncology chemotherapy education class. Can Oncol Nurs J 28:4–7. 10.5737/2368807628147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wittenberg E, Buller H, Ferrell B, Koczywas M, Borneman T (2017) Understanding family caregiver communication to provide family-centered cancer care. Semin Oncol Nurs 33:507–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wittenberg E, Ferrell B, Goldsmith J, Ruel NH (2017) Family caregiver communication tool: a new measure for tailoring communication with cancer caregivers. Psychooncology. 26:1222–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. In: Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Publications, Newbury Park [Google Scholar]