Abstract

Transition metal oxides (TMOs) are promising electrochromic (EC) materials for applications such as smart windows and displays, yet the challenge still exists to achieve good flexibility, high coloration efficiency and fast response simultaneously. MXenes (e.g. Ti3C2Tx) and their derived TMOs (e.g. 2D TiO2) are good candidates for high-performance and flexible EC devices because of their 2D nature and the possibility of assembling them into loosely networked structures. Here we demonstrate flexible, fast, and high-coloration-efficiency EC devices based on self-assembled 2D TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures, with the Ti3C2Tx layer as the transparent electrode, and the 2D TiO2 layer as the EC layer. Benefiting from the well-balanced porosity and connectivity of these assembled nanometer-thick heterostructures, they present fast and efficient ion and electron transport, as well as superior mechanical and electrochemical stability. We further demonstrate large-area flexible devices which could potentially be integrated onto curved and flexible surfaces for future ubiquitous electronics.

Subject terms: Two-dimensional materials, Electronic devices

Though two-dimensional (2D) nanocomposite materials have been attractive for flexible electrochromic (EC) devices, achieving both high performance and durability remains a challenge. Here, the authors report high-performance, environmentally stable 2D MXene/transition metal oxide-based EC devices.

Introduction

Electrochromic (EC) materials, which can change their optical absorption reversibly due to the electrochemical redoxation with inserted ions under an applied potential1–3, have shown great promise in applications such as displays, smart windows and optical camouflage3–5. With the growing interest in bringing electrochromism to the field of flexible and wearable electronics in recent years, incorporating the functionality of flexibility to EC devices while maintaining high energy efficiency, fast switching speed and long durability has become increasingly critical6,7. However, this is an extremely challenging task because: (a) both the EC performance and the mechanical properties are nontrivially correlated with the materials of choice, their nanoscale formations, and the assembly approach; and (b) the co-optimization of the transparent conductive electrode and the EC material, as well as the way to integrate them, are needed.

Recently, two-dimensional (2D) transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides (referred to as MXenes) have emerged as promising nanoscale electronic materials with good electrochemical stability8,9. They have also been reported as promising templates for the synthesis of functional micro/nanostructured materials, such as transition metal oxides (TMOs), alkali-metal titanates, and their hybrids10,11. Owing to their unique optical and electrical properties, MXenes and their derivatives have demonstrated their potential in the application of energy storage, catalysis, and electronics12–14. More importantly, 2D nanosheets of both MXenes and their derivatives can be produced in liquid phase scalably, which makes it easy for constructing self-assembled films and hybrid structures, thus suitable for device applications in large scale.

We propose that self-assembled MXene/TMO heterostructures, with the MXenes as the flexible transparent electrode, and the TMOs (derived from the MXenes) as the flexible EC layer, are promising for high performance and flexible EC devices, yet it has never been explored previously. In addition to the advantage of the easiness of fabrication and integration with different functional components from MXene derivatives as mentioned above, an even more important reason is that the nanosheets network of TMOs, such as tungsten oxide (WO3) and titanium oxide (TiO2), can potentially realize not only superior EC properties, but also reliable mechanical and chemical stability among various candidates of EC materials. First, these inorganic materials are long-lasting and robust against environmental factors such as high temperature, ultraviolet radiation, and mechanical wear15–17, as compared to their organic counterparts18. Second, the nanostructured TMO network, especially in the form of 2D nanosheets, improves electrical and ionic transport significantly, because: (a) the increased surface-to-volume ratio of nanosheets as compared to the bulk forms leads to larger interface areas with the electrolyte and the shorter ion diffusivity pathways within the nanostructured channels;3,15 and (b) the 2D formation of the nanostructures makes the contact area between adjacent nanosheets much larger than that between 1D or 0D structures (nanowires or quantum dots)19, which promotes the internanosheets electron transfer20. Finally, networks of 2D nanostructures also help to redistribute the induced strain evenly, thus improving both the mechanical strength and the flexibility of the film, which is fundamentally more advantageous than 1D or 0D nanostructures for flexible devices21.

As a proof-of-concept demonstration, we successfully assemble Ti3C2Tx (T = O, OH, or F) and the derived TiO2 nanosheets into uniform nanometer-thick films at a liquid-liquid interface, and fabricate EC devices based on the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures on a flexible substrate. Due to the much improved ion diffusion and electron conductivity of assembled single-flake-layer TiO2 film and the 2D nature of both the MXene electrode and the TiO2 EC layer, our devices are among the best flexible EC devices with the fastest coloration speed, the highest coloration efficiency and superior electrochemical stability. We further demonstrate a large-area flexible device which could potentially be integrated with arbitrary curved and flexible surfaces for future ubiquitous electronics.

Results

Preparation of 2D TiO2 via the chemical conversion from Ti3C2Tx

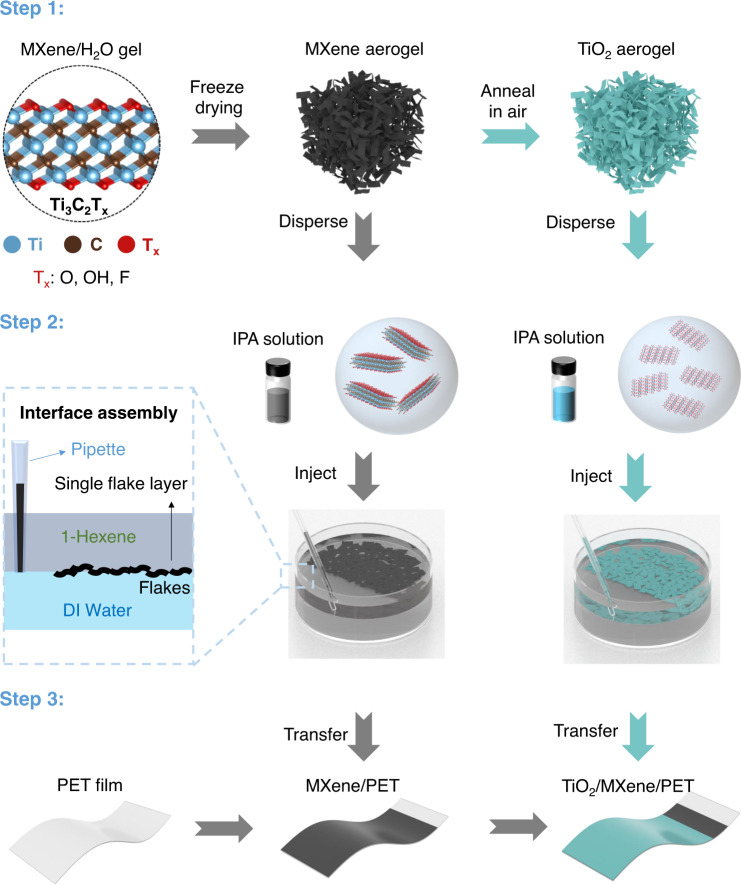

Figure 1 illustrates the fabrication process of the self-assembled TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructure on a flexible structure as the core functional component of EC devices. The fabrication process consists of three steps: First, the Ti3C2Tx nanosheet dispersion in deionized (DI) water is obtained from selective etching of Ti3AlC2 powder (MAX phase)22, and diluted to 0.2 mg/L, followed by the formation of the Ti3C2Tx aerogel through freeze drying. The Ti3C2Tx aerogel is then annealed in air at 400 °C to fully be converted to the TiO2 aerogel; Second, the Ti3C2Tx (TiO2) aerogels are dispersed into isopropyl alcohol (IPA) to form the Ti3C2Tx (TiO2) solutions, which are then injected into the interface between hexane and water, where the nanosheets self-assemble into uniform nanometer-thick films; Last, the self-assembled Ti3C2Tx film and TiO2 film are transferred sequentially onto a flexible polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate to form TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures, in which the Ti3C2Tx film serves as the transparent conductive electrode, and the TiO2 film serves as the EC layer in EC devices (more details about film assembly and transfer processes are in Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplementary Movie 1 and Supplementary Movie 2 in Supplementary Information).

Fig. 1. Fabrication process of TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructure on a flexible substrate.

Step 1: MXene (Ti3C2Tx, crystal structures in the left panel, is drawn by Vesta software) aerogel is obtained by freeze drying of the Ti3C2Tx nanosheets dispersion and the derived TiO2 aerogel is obtained by annealing the MXene aerogel in air at 400 °C. Step 2: Ti3C2Tx and TiO2 2D nanosheets are dispersed, respectively, in IPA, injected into the interface between hexene and DI water, and self-assembled into nanometer-thick Ti3C2Tx and TiO2 films. Step 3: the thin films are transferred onto a flexible substrate (e.g., PET) in a layer-by-layer fashion to realize the TiO2/MXene heterostructure, where the TiO2 layer serves as the electrochromic component, and the MXene layer serves as the transparent electrode.

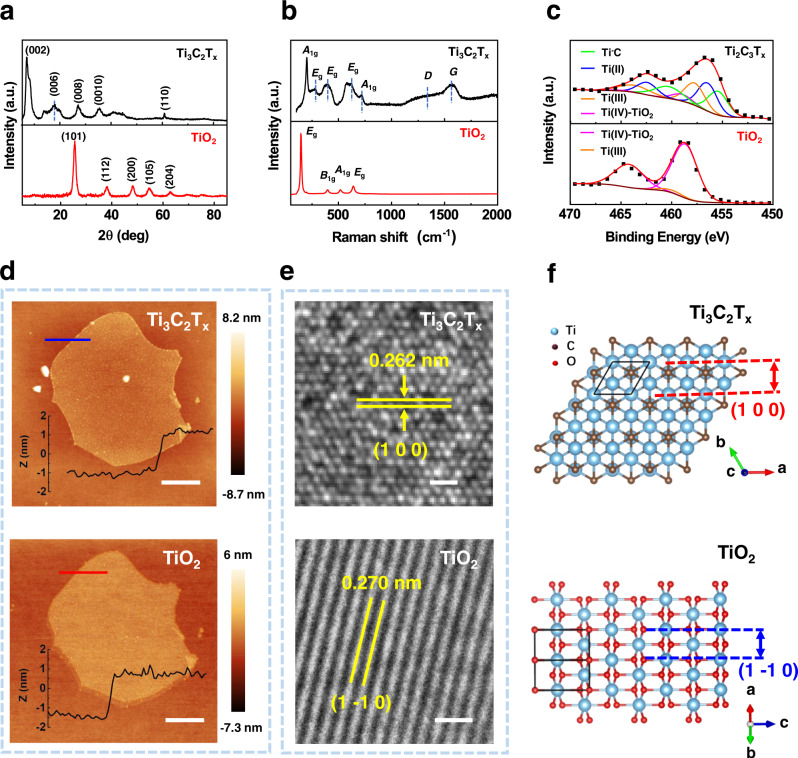

To obtain the anatase phase of TiO2, which has been demonstrated a good EC material23, we anneal the Ti3C2Tx aerogel in air at 400 °C for 50 h. X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Raman spectroscopy of the flakes are measured before and after the thermal annealing process to investigate the compositional and the structural changes. As shown in Fig. 2a, after annealing in air at 400 °C, new peaks at 26°, 38°, 48°, 54°, and 63° appear in the XRD spectra, corresponding to the (101), (112), (200), (105), and (204) planes of the anatase phase of TiO224. Raman spectra of Ti3C2Tx flakes after annealing confirms the conversion from Ti3C2Tx to TiO2 (Fig. 2b), where peaks at 145 cm−1 (Eg), 398 cm−1 (B1g), 518 cm−1 (B1g), and 639 cm−1 (Eg) match well with the Raman features of the anatase phase of TiO225. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) characterization further suggests the transformation from Ti3C2Tx to TiO2. It’s clearly seen that the peaks for the Ti element in Ti3C2Tx (i.e., Ti-C 2p3/2 (455.3 eV), Ti(II) 2p3/2 (456.1 eV), Ti(III) 2p3/2 (457.2)) disappear after the annealing (Fig. 2c top and Supplementary Fig. 2), while peaks at 458.8 eV and 464.8 eV, corresponding to Ti(IV) 2p3/2 and Ti(IV) 2p1/2 in TiO2, become dominant (Fig. 2c bottom)26.

Fig. 2. Conversion of Ti3C2Tx into 2D TiO2 flakes.

a XRD patterns and b Raman spectra of the Ti3C2Tx before and after annealing at 400 °C for 50 h. c XPS spectra of the Ti3C2Tx and the derived TiO2; d AFM images and height profiles of Ti3C2Tx and a derived TiO2 flake on a SiO2/Si substrate (scale bar: 2 μm); e HRTEM images of Ti3C2Tx and derived TiO2 flakes (scale bar: 1 nm); f Crystal structures of Ti3C2Tx and derived anatase phase of TiO2.

To evaluate the morphology and crystallinity of the obtained TiO2 nanosheets, optical microscopy (OM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) are used to characterize Ti3C2Tx flakes before and after the in situ conversion to TiO2. Supplementary Fig. 3 shows OM images of a typical flake (~7 µm in lateral dimension) undergoing the annealing treatment at 400 °C for 50 h, where the morphology of the flake maintains during the process. AFM images (Fig. 2d) show that the derived TiO2 flake remains the same shape as the Ti3C2Tx precursor. The surface roughness of the flake also does not change much after conversion (root mean square roughness changes from 514.3 to 528.2 pm). The thickness of the flake stays about 2 nm after being converted to TiO2. Typical TEM images (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 4) and selective area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns (insets of Supplementary Fig. 4) indicate that both Ti3C2Tx and TiO2 are in high crystallinity. Ti3C2Tx shows a lattice spacing of 0.26 nm, corresponding to its (100) plane. After annealing at 400 °C, the derived TiO2 flake shows a lattice spacing of 0.27 nm, which refers to the1–10 plane of the anatase phase of TiO2.

Moreover, when applying the conversion to the Ti3C2Tx aerogels, remained morphology is also observed after annealing at 400 °C to convert it to TiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 5). The pore size distribution in the Ti3C2Tx and TiO2 aerogels are similar (both have peaks at around 2 nm extracted from the nitrogen adsorption isotherm at 77K) (Supplementary Fig. 6). This result further suggests that the conversion reaction is confined on initial 2D Ti3C2Tx flakes, leading to the good separation of each flake in the skeleton of aerogels during the conversion process.

Although the crystal lattice is transformed drastically from hexagonal (Ti3C2Tx) to tetragonal (anatase TiO2), our results clearly demonstrate the successful production of Ti3C2Tx flakes and their derived TiO2 flakes, both of which are high-quality crystals over micrometer large area with nanometer thin thicknesses. Based on these experimental results and comparing the crystal structures of Ti3C2Tx and the anatase phase TiO2, we propose the following mechanism to interpret the transformation from Ti3C2Tx to TiO2. As shown in Fig. 2f, during the conversion, two O atoms need to replace one C atom sandwiched between two adjacent Ti layers. In this process, due to the gentle gas-solid reaction, the diffusion of Ti atoms is limited, and due to the similarity of the Ti frameworks in the Ti3C2Tx and TiO2 crystals, it does not require large rearrangement of Ti atoms during the conversion27. Thus, the morphology of the flake can be retained.

Self-assembled ultrathin MXene films as high-performance transparent electrodes

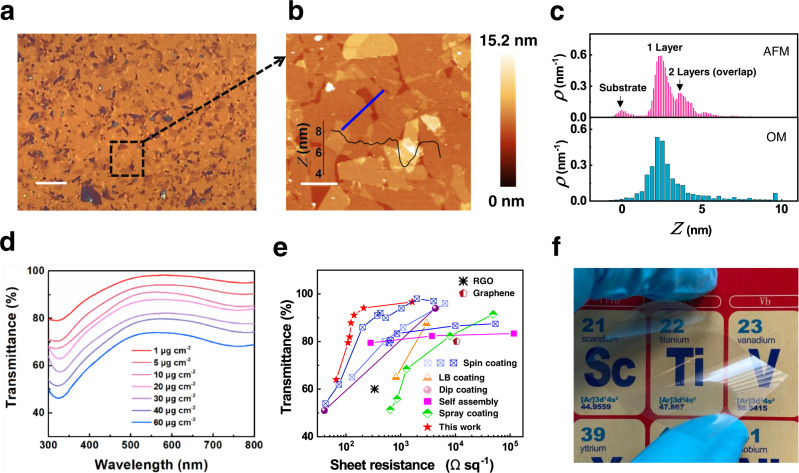

To obtain large-area homogeneous thin films of the TiO2 or Ti3C2Tx network, a liquid/liquid interfacial self-assembly (LLIA) technique is used28. Specifically, the 2D flakes/IPA dispersion is injected to the interface between hexane and water. Because of the fast dissolution of IPA into the hexane layer, a surface tension gradient is established along the interface (Marangoni force)29. Driving by this Marangoni force, the 2D flakes spreads out quickly and settles at the edge of the liquid interface, that is, either the sidewall of the container or the edge of an already assembled film. By optimizing the amount of the injected 2D flakes/IPA solution, a full coverage is achieved and a continuous 2D thin film is obtained. As shown in the OM image of Fig. 3a, the LLIA Ti3C2Tx film is homogeneous over a large area. According to the AFM image (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 7) taken at the labeled area in Fig. 3a, the Ti3C2Tx flakes are all horizontally oriented, and placed next to each other with very small overlaps. This is very different from the films produced by the spray coating or spin coating methods where the orientations of the flakes are random, and they are mostly overlapped and bundled30,31. To quantify the uniformity of the LLIA film in a large area, we extract the height profiles (Supplementary Fig. 7) from the AFM image, use it to calibrate the optical contrast of the OM image to obtain the thickness distribution over the area (Supplementary Fig. 8). The thickness distributions extracted from both the AFM image (small area) and the OM image (large area) are shown in Fig. 3c. It is observed that the peaks for both distributions appear at around 2 nm, which corresponds to the thickness of 1-layer of Ti3C2Tx flake. The second most significant peak is at around 3.8 nm, which corresponds to the overlapped area of two adjacent flakes (2 layers). These 1-layer and 2-layer regions are the key functional components for the electrical conductance, which covers 64% and 18% of the film, respectively.

Fig. 3. Characterization of the self-assembled Ti3C2Tx thin film as a transparent electrode.

a OM image of the assembled Ti3C2Tx thin film (scale bar: 10 μm); b AFM image and the height profile of the assembled Ti3C2Tx thin film in corresponding area marked in a (scale bar: 2 μm). c Thickness distributions extracted from the AFM image (top) and the OM image (bottom); the Y-axes are probability density, namely, frequency per unit height; d Transmittance spectra of Ti3C2Tx films with various concentrations of injected Ti3C2Tx; e Transmittance at 550 nm as a function of sheet resistance for the Ti3C2Tx films and data from previously reported transparent electrode technologies; RGO reduced graphene oxide, LB Langmuir–Blodgett. f Photograph of a Ti3C2Tx film deposited on a PET substrate that presents excellent transparency and flexibility.

Because of the uniform thickness distributions and the high coverage of 1-layer and 2-layer, the LLIA Ti3C2Tx films show both high optical transparency and high electrical conductance, making them ideal for the transparent electrodes of EC devices. The optical and electronic properties are evaluated by ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectrophotometry and a four-point probe resistance measurement technique. The UV-vis spectra of these films with different Ti3C2Tx area concentrations are presented in Fig. 3d, where the area concentration is defined as the mass of Ti3C2Tx per square centimeter, and tuned by the volume of 2 mg/ml Ti3C2Tx dispersion injected at the interface during the assembly. The transmittance of LLIA Ti3C2Tx at 550 nm reaches 96.8% when the area concentration is 1 µg cm−2, and decreases steadily to 64.3% as the area concentration increases to 60 µg cm−2 32. The transmittance at 550 nm versus the sheet resistance (Rs) of the LLIA films, together with the data from previously reported techniques, are plotted in Fig. 3e. The Rs value of the LLIA Ti3C2Tx film reaches 1623 Ω sq−1 at a transmittance of 96.9%, 210 Ω sq−1 at 94.1%, and 123 Ω sq−1 at 87.8%. Comparing the resistances of materials with the similar transparency, our values are lower than MXene films made by other methods like spin coating (201 Ω sq−1 at 87%), dip coating (4300 Ω sq−1 at 94%), and spray coating (7974 Ω sq−1 at 82%), and also lower than other transparent conductive materials such as graphene, and reduced graphene oxide (see Supplementary Table 1 for a summary of different transparent conductive materials)30,31,33–40. Finally, Fig. 3f shows that the LLIA Ti3C2Tx film can be transferred onto a flexible substrate (e.g., PET) uniformly in a large area (~25 cm2) with excellent optical transparency, suitable for transparent conductive electrodes for the proposed flexible EC devices.

Fast and highly efficient electrochromism in MXene/TiO2 heterostructures

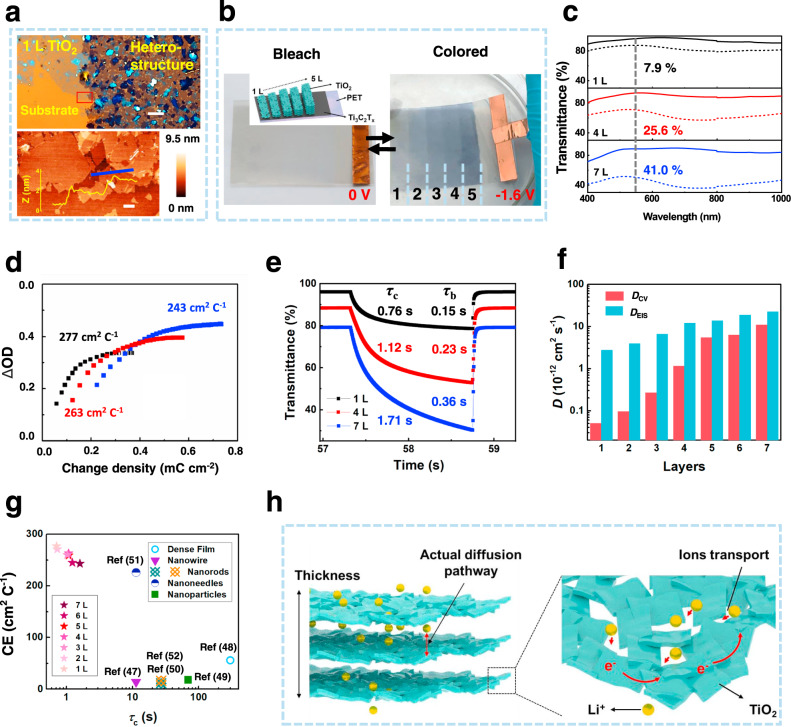

The flexible TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructure electrodes are fabricated by transferring LLIA TiO2 films on the Ti3C2Tx/PET substrates. Similar to Ti3C2Tx, TiO2 flakes in the LLIA film also connect with each other to form a porous network, with the pore size in the range of nanometers, when observed under TEM and OM measurements (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Fig. 10). The morphology of TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures are further characterized by OM, SEM, and AFM measurements. As shown in Fig. 4a, the boundary between the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructure and l-layer TiO2 film is clearly seen from the OM image. AFM characterization shows a thickness different of ~2 nm across the boundary, matching well with the thickness of 1-layer Ti3C2Tx, indicating a close contact between the TiO2 and Ti3C2Tx layers. Moreover, Supplementary Fig. 11 shows OM and SEM images of different layers (1, 4, and 7 L) of LLIA TiO2 on Ti3C2Tx films, where the porous structures can be still seen in the stacked multiple layers.

Fig. 4. Electrochromic properties of the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructure.

a OM image of a junction between a 1-layer TiO2 film and the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructure (Top) (Scale bar: 10 μm), and AFM image and the height profile of across the junction in corresponding area marked in the OM image (Bottom) (Scale bar: 1 μm); b Photographs of the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx/PET film with different layers of TiO2 at the bleaching state (no bias) and the colored state (biased at −1.6 V). Inset: structure of TiO2/Ti3C2Tx/PET film with different TiO2 layers; c Optical transmittance spectra with 1, 4, and 7 layers of TiO2 at the biases of 0 V (solid) and −1.6 V (dotted); d Optical density change (ΔOD) as a function of the injected charge density for the heterostructures with 1, 4, and 7 layers of TiO2; e Temporal response of the transmittance at 550 nm of the heterostructures with 1, 4, and 7 layers of TiO2; f Diffusion coefficients (D) of the heterostructures with 1−7 layers of TiO2 extracted from the EIS and CV measurements; g Coloration efficiency (CE) as a function of coloration time (τc) for the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures and previously reported TiO2-based structures; h Schematic of the pathways of electron conduction and ion diffusion within the self-assembled TiO2 thin film.

The heterostructure provides a metal-semiconductor junction between Ti3C2Tx and TiO2, where Ti3C2Tx serves as the transparent electrode and TiO2 serves as the electrochromic layer. Note that Ti3C2Tx has a low work function (1.6–4.4 eV)41,42, when comparing to other transparent electrodes, e.g. indium tin oxide (ITO, with the work function of 4.73 eV)43. When contacting with TiO2 (work function ~4.2 eV), the Schottky barrier between Ti3C2Tx and TiO2 is much lower or it could even be an Ohmic contact44, compared to that between ITO and TiO2. Thus, the electron transport between the Ti3C2Tx and the TiO2 layer is expected to be greatly improved in the heterostructure.

Because of the well-controlled LLIA process, it is possible to regulate the EC properties simply by the thickness of the TiO2 layer. As shown in Figs. 4b, 1–5 layers of the LLIA TiO2 film are transferred sequentially onto a PET substrate in a layer-by-layer fashion. They are almost indistinguishable at the bleach state, when no bias is applied, but become translucent with different opacity at the colored state, when emerged in an electrolyte solution (1 M LiClO4/propylene carbonate (PC)) and biased with a constant negative voltage (−1.6 V). This optical opacity induced by a negative potential is associated with the reduction of TiO2 by Li+ counterions and the formation of LixTiO245.

As the in situ UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy measurements shown (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 12), the optical modulation range ΔT changes with the increase of the number of layers of the transferred LLIA TiO2 film, where ΔT is defined as ΔT = Tb − Tc = exp(−αbL) − exp(−αcL) (Tb and Tc are the transmittance of the bleach state and the colored state, αb and αc represent absorption coefficient of the bleach and the colored state of the LLIA film, and L is the thickness of the film). Particularly, ΔT at the wavelength of 550 nm increases gradually with the layer numbers of the transferred LLIA TiO2 films (7.19%, 12.26%, 21.12%, 25.60%, 32.12%, 38.20%, and 41.09% from 1 to 7 layers) (Supplementary Table 2). ΔT reaches its maximum at around 60% with 15 layers of LLIA TiO2 films and then declines as the layers number reaches to 20. This is because the transmittance of the bleach state decreases significantly when the film becomes thick, resulting in the decrease of the optical window (Supplementary Fig. 13). We further extracted Δα = αc – αb ≈ [ln(Tc/Tb)]/L from the transmittance spectra. Compared to the TiO2-based EC film prepared using other methods (Supplementary Table 3)16,19,46–59, our LLIA TiO2 film shows a Δα of 0.12 nm−1, which is about one order of magnitude higher. This results suggest that more TiO2 per unit volume in our LLIA TiO2 film participate in the EC process. Such high utilization rate of TiO2 in the LLIA films is one of the key factors responsible for the improved EC performance.

To quantify the utilization rates of both the EC material and the pumped charge, the optical density change (ΔOD = log10(Tb/T)) as the function of the pumped charge density (Q, calculated by an integration of the driving current density over time) during the coloration half-cycle is measured and plotted in Fig. 4d. The coloration efficiencies (CE)60, defined as the slope of the ΔOD-Q plot when Q is close to 0, for the LLIA TiO2 films with 1–7 layer numbers are extracted to be 277, 271, 260, 263, 259, 245, and 243 cm2 C−1, respectively (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 2). These high CE values indicate that small amounts of charge insertion/extraction can result in a large optical modulation (normally CE values of TMO-based EC materials are lower than 100 cm2 C−1), which is a results of high utilization rates of both the EC materials and the pumped charges. High CE also guarantees the long-term electrochemical stability. As expected, the LLIA films show maintained optical contrast (up to 95% of its original value) after 500 EC cycles (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Fig. 15). This high cycling stability is essential for practical applications of the EC devices.

The coloration/bleaching time τc/τb, another important figure-of-merit for EC materials, defined as the time needed for 90% of the total optical change, is also investigated on the LLIA TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures. The temporal responses of the transmittance at 550 nm are measured as the bias is switched between −1.6 and 0 V periodically (Fig. 4e). The coloration/bleaching times for 1–7 layers of the LLIC TiO2 films are extracted to be 0.76/0.15 s, 0.73/0.12 s, 1.03/0.20 s, 1.03/0.23 s, 1.08/0.26 s, 1.23/0.29 s, and 1.71/0.36 s (also summarized in Supplementary Table 2), which are much shorter than those of reported TiO2-based EC devices (generally >10 s) and most reported inorganic materials, and comparable to those of organic EC materials (Supplementary Table 3).

Ion diffusion process inside the EC material plays a crucial role in the EC performance. To further explore the Li+ diffusion behavior in the LLIA TiO2 films during the EC process, cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) are measured (details are listed in the Method section). All LLIA films exhibit one pair of redox peaks in their CV curves, corresponding to the reduction and oxidation of TiO2 (Supplementary Fig. 16). According to the EIS results shown in Supplementary Fig. 17 and Supplementary Table 4, the equivalent series resistance (ESR) does not change much as the TiO2 thickness increases from 1 to 7 layers, and the charge-transfer resistance (Rct) only raises from 8.7 to 15.7 Ω, indicating that multilayer stacking does not decrease the conductivity and charge-transfer speed much at the interface of the TiO2 film and electrolyte.

The apparent ion diffusion coefficient D, which represents the kinetics of ion insertion/extraction in the EC film, can be extracted either from the scanning-rate-dependent CV measurements, or from the Warburg region of the Bode plot obtained from the EIS measurements (see methods for details about the extraction methods of D)61. As shown in Fig. 4f, the D values extracted from the CV and from the EIS measurements are 5.05 × 10−14, 9.63 × 10−14, 2.68 × 10−13, 1.15 × 10−12, 5.45 × 10−12, 6.29 × 10−12, and 1.10 × 10−11 cm2 s−1, and 2.75 × 10−12, 3.94 × 10−12, 6.59 × 10−12, 1.21 × 10−11, 1.39 × 10−11, 1.88 × 10−11, 2.24 × 10−11 cm2 s−1, respectively, as the number of layer of the TiO2 film increases from 1 to 7. The positive correlation between D and the layer number is attributed to the increased effective electrochemical area of the LLIA TiO2 film due to its high surface-to-volume ratio, which will be explained later.

To benchmark the overall EC performance, the values of CE and τc of the LLIA TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures as well as previously reported EC materials are summarized in Fig. 4g and Supplementary Table 3. It is clearly observed that both the CE and the response time of our proposed structures are several times or even one order of magnitude better than those from both other materials such as WO3, and other nanostructured TiO2, including dense films and other 0D or 1D nanostructures, and comparable to organic materials. Moreover, the good cycling stability of our LLIA TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures could address the ultraviolet/electrochemical decomposition issues in traditional organic materials in practical applications18.

We believe that the superiority of the EC performance of the LLIA TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures mainly results from the 2D nature of the TiO2 flakes as well as the loosely networked structures. To understand this, we propose two possible ion transport pathways15. The first ion transport pathway is that the Li+ ions enters the EC material only on the top surface, and the redoxation deeper into the EC material is accessed by inter-crystal-lattice diffusion of Li+ ions; whereas in the second ion transport pathway (as illustrated in Fig. 4h), Li+ ions could travel to all the surfaces of individual EC nanostructures efficiently in the liquid phase, and as a result, the diffusion and the redoxation take place throughout the entire EC nanostructures simultaneously. For dense films, only the first pathway takes place, resulting in very bad coloration efficiency and very slow coloration/bleaching time; while for nanostructured films (including our 2D nanostructures and previously reported 0D or 1D nanostructures), the second pathway, which is much more efficient and much faster, starts to play an important role. The higher probability the second pathway takes place in a nanostructured film, the better EC performance it can achieve.

Our experimental results suggest that the second pathway is the dominating Li+ ion transport mechanism in our self-assembled 2D TiO2 films. First, the high CE and its small decrease with the thickness suggest that Li+ ions can easily access all the TiO2 flakes regardless of the depth of them from the top surface of the film. Second, the color change time τ (τc or τb) is fast and stays almost the same with different thicknesses. Given that τ is proportional to the square of the depth of the diffusion, we speculate that the effective diffusion depth is likely to be determined by the average thickness of individual TiO2 flakes, rather than the thickness of the entire assembled TiO2 film. Last, the increasing trend between D and the thickness indicates that it is less likely that the extremely slow internanosheet diffusion is contributed to the measured apparent diffusion coefficient. Instead, D follows a parabolic trend with the thickness (see Supplementary Fig. 18), or the number of layers, which agrees well if considering the contribution from the electrochemical area AEC and assuming a linear increase of AEC with the number of layers, that is, D~(AEC/A)2D0 ∝ N2, where A is the geometrical area, D0 is the intrinsic diffusion coefficient, and N is the number of layers. All these experimental observations can be explained well if the performance is governed by the second ion transport pathway, in which all the surfaces of the 2D TiO2 flakes are interfacing well with the electrolyte, and the actual diffusion length is approximately the thickness of individual TiO2 flakes (Fig. 4h). As a comparison, for 1D or 0D nanostructures, although the ideal surface-to-volume might be even larger, the surfaces may not be fully exposed to the electrolyte because of the denser packing of these nanostructures in a film. Consequently, the Li+ ions have to undergo the first pathway in order to access the deeper EC materials, which tremendously limits the speed and thus reduces the coloration efficiency.

MXene/TiO2 heterostructure enabled flexible EC devices for large-area applications

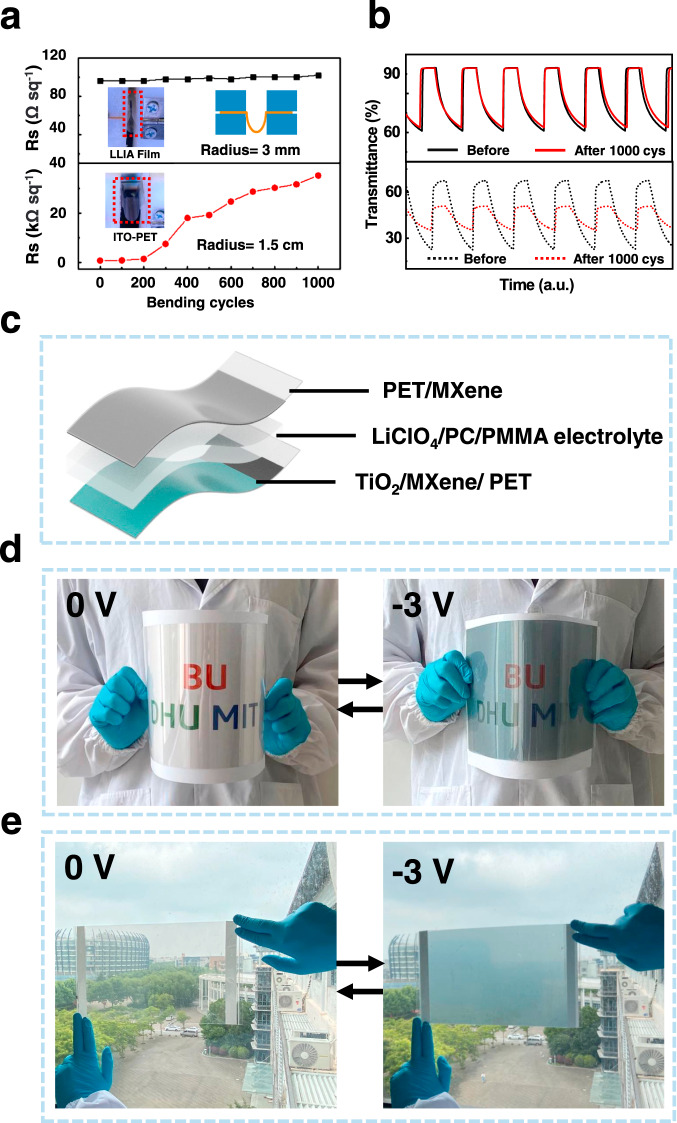

The overall flexibility of an EC device is determined by the most rigid layer. In our TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructure, both the EC layer and the transparent electrode have superior mechanical bendability. To confirm this, bending test is performed on the as-fabricated LLIA electrode. As shown in Fig. 5a, the resistance of the Ti3C2Tx/PET film increases by only 6% after 1000 bending and release cycles at a bending radius of 0.3 cm, whereas the sheet resistance of a commercial ITO/PET film increases quickly by three orders of magnitude after 1000 bending cycles even at a much larger bending radius of 1.5 cm. The EC optical switching behaviors of the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx/PET film and the TiO2/ITO/PET before and after 1000 bending cycles are also tested (Fig. 5b). ΔT of the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx/PET electrode remains at 94% of its original value after 1000 bending cycles. In contrast, ΔT of the TiO2/ITO/PET electrode drops to about 30% after 1000 cycles.

Fig. 5. Mechanical properties of the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructure and demonstration of a large-area flexible EC device.

a Comparison of the sheet resistance (Rs) of the LLIA Ti3C2Tx/PET and the ITO/PET films after 1000 bending cycles; b Comparison of the electrochromic switching behaviors of the LLIA TiO2/Ti3C2Tx/PET and the ITO/PET films after 1000 bending cycles; c Schematic diagram of the flexible solid electrochromic device; d, e As-prepared solid electrochromic device with an A4 paper size (about 20 × 30 cm) is d triggered in bending state and e attached on a window.

Finally, a large-area flexible EC device with a dimension of 30 × 20 cm are demonstrated as an example for practical large-area applications. As shown in Fig. 5c, it is composed of a LLIA TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructure on a PET substrate as the EC electrode, another LLIA Ti3C2Tx/PET film as the counter electrode, and a 1 M LiClO4/PC/Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) layer as the electrolyte. Benefiting from the exceptional optical memory effect of TiO2 based materials, the EC device can maintain its coloration state after disconnecting from the voltage supply (Fig. 5d, e), which is advantageous for energy saving in future applications. The EC device presents a uniform color distribution even in the bending state, which opens up the possibility of scaling up this technology for applications, such as flexible displays, smart windows, and other ubiquitous electronics. In addition, the flexible solid EC device also exhibits excellent cycling stability, demonstrated by the 92% transmittance presentation after 1000 EC cycles between the bias of -3 V and 1 V (S).

Discussion

In summary, high performance and flexible EC devices are realized based on assembled 2D TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures. This success benefits from several important achievements in this work, including the realization of single crystalline 2D TiO2 flakes with micrometer large lateral sizes and nanometer thin thicknesses, and the liquid/liquid interfacial self-assembly technique enabled mass production of MXene and 2D TMO films with excellent uniformity. We expect our approach to synthesize 2D TiO2 crystals to be developed to a general methodology for the synthesis of high-quality 2D MXene derivatives. Also, the self-assembled MXene films could be used as flexible, transparent, and porous electrodes in large-scale electronic, optoelectronic, and energy-harvesting applications. Our performance test clearly shows that exceptional electrochromic efficiency, fast coloration speed, and excellent mechanical flexibility are achieved simultaneously on the self-assembled 2D TMO/MXene heterostructures-based EC devices, thanks to the unique electrical, electrochemical, and mechanical properties of the networked 2D nanostructures. Finally, a large-area flexible EC device is demonstrated, paving the way for integrating EC devices to next-generation flexible and wearable electronics.

Methods

Chemicals

All the starting materials are available commercially and used as received. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) was rinsed sequentially in the baths of deionized water, acetone, and isopropanol. Ti3AlC2 (MAX-Phase, purchased from 11 Technology Co. Ltd), lithium fluoride (LiF, Alfa Aesar, 99.99%), hydrochloric acid (HCl, Fisher Chemical, 6M), 1-hexene (Acros Organics, 99%), isopropyl alcohol (IPA, Fisher Chemical, 99%), propylene carbonate (PC, Alfa Aesar, 99%), lithium perchlorate (LiClO4, Acros Organics, 99+%), and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA, ACROS Organics, M.W. 35000) were utilized without initial treatments.

Synthesis and interfacial assembly of Ti3C2Tx and 2D TiO2 films

Ti3AlC2 etching was performed following Gogosti et al.’s work22 to prepare 2D Ti3C2Tx. Briefly, 1.6 g lithium fluoride was dissolved into 5 mL of DI water with 15 mL 12 M hydrochloric acid solution in a plastic bottle as the etchant solution. Then 1 g Ti3AlC2 (MAX phase) powders was gradually added to the etchant solution within 5 min and the reaction is maintained with stirring the reactants at 40 °C in a silicon oil bath for 24 h. Etched MXene was washed with DI water, and separated through centrifugation at 1988 × g for 5 min. Washing was repeated several times until a stable dark supernatant solution of Ti3C2Tx flakes with a pH value of around 6 was obtained. The solution was subsequently centrifuged for 30 min at 3500 rpm, after which a dark sediment of Ti3C2Tx was observed and then collected.

The Ti3C2Tx sedimen was diluted to 0.2 mg/ml with DI water, and then, the solution were freeze dried at −47 °C for days to form an aerogel. To obtaine the TiO2 aerogel, the Ti3C2Tx aerogel was put in a ceramic boat and annealed at the temperature of 400 °C for 50 h with the heating rate of 1 °C/min.

To assemble the Ti3C2Tx flakes into a continuous film, the Ti3C2Tx aerogel was dispersed in an IPA solution (2 mg/ml) by sonicating for 30 min. Hexane was carefully poured on the top of DI water to setup an interface between these two liquids. Then, the Ti3C2Tx/IPA dispersion was slowly injected near the interface to form a continuous film. After removing the top hexane layer, the self-assembly film was transferred onto a substrate and annealed at 90 °C in vacuum for 50 h (<0.05 MPa).

The assembly of the TiO2 films is similar to the Ti3C2Tx assembly process. For multilayered TiO2 film, the transferred films were dried at 60 °C in vacuum for 1 h, and then treated with oxygen plasma (the oxygen gas flow rate is 50 sccm, and the plasma power is 100 W) for 30 s before each transfer cycle. The TiO2/Ti3C2Tx heterostructures were annealed at 90 °C in vacuum (<0.05 MPa) for 50 h before use.

Assembly of the Electrochromic device

The electrolyte gel was obtained by mixing 1 M LiClO4 in a PC solution and 20 wt% PMMA (relative to the LiClO4/PC solution). For the large-area (20 × 30 cm) electrode, silver paste line is screen printed around the Ti3C2Tx/PET film and then protected by continuous printed UV curing resin to improve the electrical conductivity. The EC devices were fabricated by hot pressing the electrolyte gel sandwiched betwen the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx/PET electrode and the Ti3C2Tx /PET counter electrode with a scotch tape spacer (with the thickness of 1 mm) at 60 °C.

Material characterization

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were measured using an X-ray diffractometer (Bruker AXS X8 Proteum-R instrument) with the radiation at 40 kV and 200 mA. Raman spectroscopy measurements were performed on a Renishaw inVia Raman microscope equipped with a 532 nm laser line (The laser power on the samples is about 1.6 mW). All the spectra in comparison were taken under the same conditions. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurements were performed on a FEI Tecnai Osiris TEM. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) was measured on a JEOL 2100 TEM. AFM measurements were conducted on a Bruker Dimension system. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed using a PHI Versaprobe II. The UV-vis spectroscopy was carried out using a Agilent CARY 5000.

Electrochemical measurements and parameter extraction

Electrochemical measurements were carried out in a PC solution containing 1 M LiClO4 electrolyte using three-electrode electrochemical cells with the TiO2/Ti3C2Tx/PET films as the working electrodes, a platinum plate as the counter electrode, and a freshly prepared Ag/Ag+ as the pseudo-reference electrode (calibrated by ferrocene). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and cycle voltammetry (CV) were conducted by an electrochemical workstation (Bio-logic SAS, VSP-300) over a frequency range of 100 mHz–1000 KHz.

The measured EIS spectra was fitted with a circuit model illustrated in u. The Nyquist plot of all films is composed of three parts: an equivalent series resistance (ESR) in series with a semicircle consisting of a non-faradaic double layer capacitance (Cdl) and a charge-transfer resistance (Rct) at high frequency; a 45° linear region representing the Warburg element (W), which captures the ion diffusion process at medium frequency; and a line related to the capacitive charging behavior of the pseudo-capacitance (Cp) of TiO2 film and its bulk resistance (Rp) at low frequency.

The apparent ion diffusion coefficient D can be extracted from both the EIS measurements and the CV measurements. In the first method, DEIS can be calculated from the Warburg region according to Eqs. (1) and (2):61,62

| 1 |

| 2 |

where σ is the slope of Zw against ω−1/2, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, A is the effective working area (geometrical area), n is the number of electrons involved in the electrochemical reaction, F and C are the Faraday constant and the molar concentration of Li+ ions.

In the second method, the apparent ion diffusion coefficients DCV can be calculated by:63

| 3 |

where v represents the potential sweeping rate, ip represents the peak current density.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

H.W. and R.L. acknowledge the financial support of the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.51972054) and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (18D110308). X.L., J.C., T.L., and T.P. acknowledge the support from Semiconductor Research Corporation (SRC). X.L., J.C., and T.L. also acknowledge the support from the Department of Energy under Award No. DE-SC0021064. X.L. acknowledge the membership of the Photonics Centers at Boston University. R.L. acknowledges the support of Graduate Student Innovation Fund of Donghua University (CUSF-DH-D-2019002).

Author contributions

R.L. and X.M. performed most of experiments. R.L., X.M., X.Z., and L.W. prepared the samples, J.L., J.C., H.G., and T.L. characterized the samples. G.W., C.H., and Y.L. analyzed the data, Q.Z., Y.Li, Y.L., H.W., T.P., and X.L. designed experiments. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ran Li, Xiaoyuan Ma.

Contributor Information

Yuxuan Lin, Email: yxlin@berkeley.edu.

Hongzhi Wang, Email: wanghz@dhu.edu.cn.

Xi Ling, Email: xiling@bu.edu.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21852-7.

References

- 1.Rosseinsky DR, Mortimer RJ. Electrochromic systems and the prospects for devices. Adv. Mater. 2001;13:783–793. doi: 10.1002/1521-4095(200106)13:11<783::AID-ADMA783>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somani PR, Radhakrishnan S. Electrochromic materials and devices: present and future. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2003;77:117–133. doi: 10.1016/S0254-0584(01)00575-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cong S, Tian Y, Li Q, Zhao Z, Geng F. Single-crystalline tungsten oxide quantum dots for fast pseudocapacitor and electrochromic applications. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:4260–4267. doi: 10.1002/adma.201400447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortimer RJ, Dyer AL, Reynolds JR. Electrochromic organic and polymeric materials for display applications. Displays. 2006;27:2–18. doi: 10.1016/j.displa.2005.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang S, Cao S, Zhang T, Fisher A, Lee JY. Al3+ intercalation/de-intercalation-enabled dual-band electrochromic smart windows with a high optical modulation, quick response and long cycle life. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018;11:2884–2892. doi: 10.1039/C8EE01718B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yan C, et al. Stretchable and wearable electrochromic devices. ACS Nano. 2014;8:316–322. doi: 10.1021/nn404061g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wen RT, Granqvist CG, Niklasson GA. Eliminating degradation and uncovering ion-trapping dynamics in electrochromic WO3 thin films. Nat. Mater. 2015;14:996–1001. doi: 10.1038/nmat4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu Z, et al. Rational design of flexible two-dimensional MXenes with multiple functionalities. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:11980–12031. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, et al. Recent progress and advances in the environmental applications of MXene related materials. Nanoscale. 2020;12:3574–3592. doi: 10.1039/C9NR08542D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shahzad A, et al. Heterostructural TiO2/Ti3C2Tx (MXene) for photocatalytic degradation of antiepileptic drug carbamazepine. Chem. Eng. J. 2018;349:748–755. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.05.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong Y, et al. Ti3C2 MXene-derived sodium/potassium titanate nanoribbons for high-performance sodium/potassium ion batteries with enhanced capacities. ACS Nano. 2017;11:4792–4800. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pang J, et al. Applications of 2D MXenes in energy conversion and storage systems. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:72–133. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00324F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cai G, Ciou JH, Liu Y, Jiang Y, Lee PS. Leaf-inspired multiresponsive MXene-based actuator for programmable smart devices. Sci. Adv. 2019;5:eaaw7956. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salles P, et al. Electrochromic effect in titanium carbide MXene thin films produced by dip-coating. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019;29:1809223. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201809223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Shim M, Guyot-Sionnest P. Electrochromic nanocrystal quantum dots. Science. 2001;291:2390–2392. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen JZ, Ko WY, Yen YC, Chen PH, Lin KJ. Hydrothermally processed TiO2 nanowire electrodes with antireflective and electrochromic properties. ACS Nano. 2012;6:6633–6639. doi: 10.1021/nn300787r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nah YC, Ghicov A, Kim D, Berger S, Schmuki P. TiO2-WO3 composite nanotubes by alloy anodization: growth and enhanced electrochromic properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16154–16155. doi: 10.1021/ja807106y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen J, Madsen MV, Krebs FC. Photochemical stability of electrochromic polymers and devices. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2013;1:4826–4835. doi: 10.1039/c3tc30751d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azam A, et al. Two-dimensional WO3 nanosheets chemically converted from layered WS2 for high-performance electrochromic devices. Nano Lett. 2018;18:5646–5651. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b02150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li K, Zhang Q, Wang H, Li Y. Lightweight, highly bendable and foldable electrochromic films based on all-solution-processed bilayer nanowire networks. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2016;4:5849–5857. doi: 10.1039/C6TC01516F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang, L. et al. High-performance flexible electrochromic device based on facile semiconductor-to-metal transition realized by WO3·2H2O ultrathin nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 3, 1936 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Alhabeb M, et al. Guidelines for synthesis and processing of two-dimensional titanium carbide (Ti3C2Tx MXene) Chem. Mater. 2017;29:7633–7644. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b02847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalifa ZS, Lin H, Ismat S. Shah, structural and electrochromic properties of TiO2 thin films prepared by metallorganic chemical vapor deposition. Thin Solid Films. 2010;518:5457–5462. doi: 10.1016/j.tsf.2010.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van de Krol R, Goossens A, Meulenkamp EA. In situ X‐ray diffraction of lithium intercalation in nanostructured and thin film anatase TiO2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1999;146:3150. doi: 10.1149/1.1392447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khatim O, et al. Amorphous–anatase phase transition in single immobilized TiO2 nanoparticles. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2013;558:53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2012.12.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao XT, et al. Ultrathin MXene nanosheets decorated with TiO2 quantum dots as an efficient sulfur host toward fast and stable Li–S batteries. Small. 2018;14:1802443. doi: 10.1002/smll.201802443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao J, et al. Realization of 2D crystalline metal nitrides via selective atomic substitution. Sci. Adv. 2020;6:eaax8784. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax8784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu X, Prévot MS, Guijarro N, Sivula K. Self-assembled 2D WSe2 thin films for photoelectrochemical hydrogen production. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7596. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sternling CV, Scriven LE. Interfacial turbulence: hydrodynamic instability and the marangoni effect. AIChE J. 1959;5:514–523. doi: 10.1002/aic.690050421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang C, et al. Transparent, flexible, and conductive 2D titanium carbide (MXene) films with high volumetric capacitance. Adv. Mater. 2017;29:1702678. doi: 10.1002/adma.201702678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hantanasirisakul K, et al. Fabrication of Ti3C2Tx MXene transparent thin films with tunable optoelectronic properties. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2016;2:1600050. doi: 10.1002/aelm.201600050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X, et al. Large-area ultrathin graphene films by single-step marangoni self-assembly for highly sensitive strain sensing application. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016;26:1322–1329. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201504717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Min K, et al. A facile route to fabricate stable reduced graphene oxide dispersions in various media and their transparent conductive thin films. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012;383:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ying G, Dillon AD, Fafarman AT, Barsoum MW. Transparent, conductive solution processed spincast 2D Ti2CTx (MXene) films. Mater. Res. Lett. 2017;5:391–398. doi: 10.1080/21663831.2017.1296043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mariano M, et al. Solution-processed titanium carbide MXene films examined as highly transparent conductors. Nanoscale. 2016;8:16371–16378. doi: 10.1039/C6NR03682A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weng G-M, et al. Layer-by-layer assembly of cross-functional semi-transparent MXene-carbon nanotubes composite films for next-generation electromagnetic interference shielding. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018;28:1803360. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201803360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim SJ, et al. Interfacial assembly of ultrathin, functional MXene films. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2019;11:32320–32327. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b12539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang C, Nicolosi V. Graphene and MXene-based transparent conductive electrodes and supercapacitors. Energy Storage Mater. 2019;16:102–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ensm.2018.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ying G, Kota S, Dillon AD, Fafarman AT, Barsoum MW. Conductive transparent V2CTx (MXene) films. FlatChem. 2018;8:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.flatc.2018.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salles P, Quain E, Kurra N, Sarycheva A, Gogotsi Y. Automated scalpel patterning of solution processed thin films for fabrication of transparent MXene microsupercapacitors. Small. 2018;14:1802864. doi: 10.1002/smll.201802864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schultz T, Frey NC, Hantanasirisakul K, Park S, May SJ, Shenoy VB, Gogotsi Y, Koch N. Surface termination dependent work function and electronic properties of Ti3C2Tx MXene. Chem. Mater. 2019;31:6590–6597. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b00414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang H, et al. Formation of Quasi-core-shell In2S3/anatase TiO2@ metallic Ti3C2Tx hybrids with favorable charge transfer channels for excellent visible-light-photocatalytic performance. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018;233:213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.04.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park Y, Choong V, Gao Y, Hsieh BR, Tang CW. Work function of indium tin oxide transparent conductor measured by photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996;68:2699–2701. doi: 10.1063/1.116313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng C, et al. High efficiency photocatalytic hydrogen production over ternary Cu/TiO2@ Ti3C2Tx enabled by low-work-function 2D titanium carbide. Nano Energy. 2018;53:97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.08.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ghicov A, et al. TiO2 nanotubes: H+ insertion and strong electrochromic effects. Electrochem. Commun. 2006;8:528–532. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2006.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dinh NN, Oanh NTHT, Long PD, Bernard MC, Goff AH. Electrochromic properties of TiO2 anatase thin films prepared by a dipping sol-gel method. Thin Solid Films. 2003;423:70–76. doi: 10.1016/S0040-6090(02)00948-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tebby Z, et al. Low-temperature UV-processing of nanocrystalline nanoporous thin TiO2 films: an original route toward plastic electrochromic systems. Chem. Mater. 2008;20:7260–7267. doi: 10.1021/cm802030c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen Y, et al. Design and construction of hierarchical TiO2 nanorod arrays by combining layer-by-layer and hydrothermal crystallization techniques for electrochromic application. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;440:217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.01.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patil RA, Devan RS, Liou Y, Ma YR. Efficient electrochromic smart windows of one-dimensional pure brookite TiO2 nanoneedles. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2016;147:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2015.12.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Y, et al. Core-shell nanorod arrays of crystalline/amorphous TiO2 constructed by layer-by-layer method for high-performance electrochromic electrodes. Electrochim. Acta. 2017;251:546–553. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2017.08.170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alesanco Y, et al. Plastic electrochromic devices based on viologen-modified TiO2 films prepared at low temperature. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2016;157:624–635. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2016.07.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li R, et al. Ion-transport design for high-performance Na+-based electrochromics. ACS Nano. 2018;12:3759–3768. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b00974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang JL, Lu YR, Li HH, Liu JW, Yu SH. Large area co-assembly of nanowires for flexible transparent smart windows. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:9921–9926. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Q, Tsai CY, Li LJ, Liaw DJ. Colorless-to-colorful switching electrochromic polyimides with very high contrast ratio. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1239. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09054-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hwang E, et al. An electrolyte-free flexible electrochromic device using electrostatically strong graphene quantum dot–viologen nanocomposites. Adv. Mater. 2014;26:5129–5136. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cao S, Zhang S, Zhang T, Lee JY. Fluoride-assisted synthesis of plasmonic colloidal Ta-doped TiO2 nanocrystals for near-infrared and visible-light selective electrochromic modulation. Chem. Mater. 2018;30:4838–4846. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b02196. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Macher S, et al. New roll‐to‐roll processable PEDOT‐based polymer with colorless bleached state for flexible electrochromic devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020;30:1906254. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201906254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang S, et al. Preparation, characterization, and electrochromic properties of nanocellulose-based polyaniline nanocomposite films. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2017;9:16426–16434. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b02794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li H, Firby CJ, Elezzabi AY. Rechargeable aqueous hybrid Zn2+/Al3+ electrochromic batteries. Joule. 2019;3:2268–2278. doi: 10.1016/j.joule.2019.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee SH, et al. Electrochromic coloration efficiency of a-WO3-y thin films as a function of oxygen deficiency. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999;75:1541–1543. doi: 10.1063/1.124782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rui XH, Ding N, Liu J, Li C, Chen CH. Analysis of the chemical diffusion coefficient of lithium ions in Li3V2(PO4)3 cathode material. Electrochim. Acta. 2010;55:2384–2390. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2009.11.096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pehlivan E, Niklasson GA, Granqvist CG, Georén P. Ageing of electrochromic WO3 coatings characterized by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Phys. Status Solidi A. 2010;207:1772–1776. doi: 10.1002/pssa.200983758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang SB, Lai MO, Lu L. Study on Li+-ion diffusion in nano-crystalline LiMn2O4 thin film cathode grown by pulsed laser deposition using CV, EIS and PITT techniques. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2008;111:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2008.03.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.