Abstract

Patients with atrial high-rate episodes (AHRE) are at higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). The cutoff threshold for AHRE duration for MACE, with/without history of atrial fibrillation (AF) or myocardial infarction (MI), is unknown. A total of 481 consecutive patients with/without history of AF or MI receiving dual-chamber pacemaker implantation were included. The primary outcome was a composite endpoint of MACE after AHRE ≥ 5 min, ≥ 6 h, and ≥ 24 h. AHRE was defined as > 175 bpm (MEDTRONIC) or > 200 bpm (BIOTRONIK) lasting ≥ 5 min. Cox regression analysis with time-dependent covariates was conducted. Patients’ mean age was 75.3 ± 10.7 years and 188 (39.1%) developed AHRE ≥ 5 min, 115 (23.9%) ≥ 6 h, and 83 (17.3%) ≥ 24 h. During follow-up (median 39.9 ± 29.8 months), 92 MACE occurred (IR 5.749%/year, 95% CI 3.88–5.85). AHRE ≥ 5 min (HR 5.252, 95% CI 2.575–10.715, P < 0.001) and ≥ 6 h (HR 2.548, 95% CI 1.284–5.058, P = 0.007) was independently associated with MACE, but not AHRE ≥ 24 h. Patients with history of MI (IR 17.80%/year) had higher MACE incidence than those without (IR 3.77%/year, p = 0.001). Significant differences were found between MACE patients with/without history of AF in AHRE ≥ 5 min but not AHRE ≥ 6 h or ≥ 24 h. Patients with dual-chamber pacemakers who develop AHRE have increased risk of MACE, particularly after history of AF or MI.

Subject terms: Cardiology, Medical research

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia encountered in clinical practice and is a major cause of preventable thromboembolic disease, namely stroke or systemic embolism1. Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (PAF), which is diagnosed by 12-lead electrocardiography, is transient and infrequent, and may be asymptomatic. The increased use of cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) has provided the technical ability to monitor atrial rhythm long term, and recent studies have focused on subclinical AF or atrial high-rate episodes (AHRE) detected by CIEDs, even in asymptomatic patients. Results of some studies have demonstrated that AHRE is associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events2. Increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) also have been studied in patients with AF3 and occasionally those with AHRE4. However, the impact of both history of AF or myocardial infarction (MI) and the duration of AHRE on MACE lacks sufficient evidence to reach a conclusion.

Accordingly, we retrospectively examined the associations between different cutoff durations of AHRE and the incidence rates of MACE in patients with dual chamber permanent pacemakers with or without history of AF or MI.

Methods

Patients ≥ 18 years of age with dual chamber permanent pacemakers (MEDTRONIC or BIOTRONIK) who were treated in the Cardiology Department of National Cheng Kung University Hospital from January 2015 to August 2019 were recruited. The procedures followed were in accordance with the “Declaration of Helsinki” and the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (the Institutional Review Board of National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan (B-ER-108-278)). All included patients provided signed informed consent to participate.

Data collection and definitions

Patients’ medical history and data of co-morbidities and echocardiographic parameters were collected from chart records for retrospective evaluation. Diabetes mellitus was defined by the presence of symptoms and a casual plasma glucose concentration ≥ 200 mg/dL, fasting plasma glucose concentration ≥ 126 mg/dL, 2-h plasma glucose concentration ≥ 200 mg/dL from a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test, or taking medication for diabetes mellitus, as previously described5. Hypertension was defined as in-office systolic blood pressure (SBP) values ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) values ≥ 90 mmHg or taking antihypertensive medication6. Dyslipidemia was defined as low-density lipoprotein ≥ 140 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein < 40 mg/dL, triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL, or taking medication for dyslipidemia7. Chronic kidney disease was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/ min / 1.73 m28. Acute coronary syndrome was defined as either an acute myocardial infarction (AMI; ST-elevation MI or non-ST elevation MI) or unstable angina9. Patients with previous ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack were considered to have cerebrovascular disease. The history of AF was defined as any documented AF in 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) or Holter recordings, before the date of pacemaker implantation. AHRE were extracted from the devices via telemetry at each office visit every 3 to 6 months4. AHRE electrograms were reviewed by at least one experienced electrophysiologist, who cautiously considered the possibility that AHRE included lead noise, far-field R-waves, or other supraventricular tachy-arrhythmias and visually verified AF in the detected AHRE. Atrial sensitivity was initially programmed to 0.2 mV with bipolar sensing of BIOTRONIK and 0.3 mV with bipolar sensing of MEDTRONIC.

The primary endpoint for this study was the occurrence of MACE as recorded in patients’ charts after the date of implantation of pacemakers, including ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), unstable angina, heart failure with acute exacerbation4, cardiovascular hospitalization (peripheral artery disease or stable angina) and cardiac death. AHRE was defined as atrial rate > 175 bpm (MEDTRONIC) or > 200 bpm (BIOTRONIK) and lasting for at least 5 min of atrial tachyarrhythmia recorded by the devices on any day during the study period. We also divided the different AHRE durations by time, including ≥ 5 min, ≥ 6 h and ≥ 24 h, to evaluate the cutoff threshold for MACE. If the patient had multiple AHREs, the longest AHRE duration was used for analysis. Then, if the patient’s longest AHRE duration was 24 h, this patient would be counted in AHRE ≥ 5 min, ≥ 6 h, and ≥ 24 h.

Statistical analysis

Among baseline characteristics, categorical variables are presented as percentages. Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations if normally distributed and median, interquartile range (IQR) if not normally distributed. Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables, and a 2-sample student’s t test for normally distributed continuous variables or Mann–Whitney U test if not normally distributed. The receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) area under the curve (AUC) of AHRE and the associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) were investigated for associations with future MACE. The cutoff values were chosen based on the results of ROC curve analysis and used to evaluate the associated values of AHRE, in minutes, for determining endpoints. Cox regression analysis was used to identify variables associated with AHRE occurrence, reported as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Indicators of AHRE ≥ 5 min, ≥ 6 h, and ≥ 24 h were determined separately as time-dependent covariates in multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression and survival curves were generated for patients without MACE. If the p value in univariable analysis was < 0.05, the parameter was entered into multivariable analysis, except for devices, which were essential confounders because of different detecting rates in AHRE definitions. Because LVEF was significantly associated with heart failure (Tables 3 and 4), heart failure was selected for inclusion into multivariable analysis. Because mitral E/e’ ratio was significantly associated with LA diameter, LA diameter was selected for inclusion into multivariable analysis. Because drug history was significantly associated with history of heart failure and myocardial infarction, it was not entered into multivariable analysis. Only mitral E/e’ ratio of echocardiographic parameter was included in multivariable analysis (Table 5). For all comparisons, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical package version 23.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA).

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis with time-dependent covariates for MACE predictors in patients with AHREs ≥ 5 min (Model A), ≥ 6 h (Model B), ≥ 24 h (Model C).

| Variables | All patients (n = 481) | Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) | P | Multivariable Cox regression | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | Model B | Model C | |||||||||||

| Yes (N = 63) | No (N = 418) | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Age (years) | 77.0,14.0 | 77.0,12.0 | 76.5,16.0 | 0.467 | |||||||||

| Gender | 0.269 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 259(53.8%) | 38(60.3%) | 221(52.9%) | ||||||||||

| Female | 222(46.2%) | 25(39.7%) | 197(47.1%) | ||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.5,2.9 | 25.1,2.6 | 24.5,3.0 | 0.258 | |||||||||

| Device | 0.584 | 1.252 | 0.602–2.604 | 0.548 | 1.003 | 0.497–2.022 | 0.994 | 0.888 | 0.447–1.763 | 0.733 | |||

| Metronic | 320(66.5%) | 40(63.5%) | 280(67.0%) | ||||||||||

| BIOTRONIK | 161(33.5%) | 23(36.5%) | 138(33.0%) | ||||||||||

| Primary indication | 0.212 | ||||||||||||

| Sinus node dysfunction | 340(70.7%) | 50(79.4%) | 290(69.4%) | ||||||||||

| Atrioventricular block | 135(28.1%) | 13(20.6%) | 122(29.2%) | ||||||||||

| Other | 6(1.2%) | 0(0%) | 6(1.4%) | ||||||||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| HAS-BLED | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 451(93.8%) | 62(98.4%) | 389(93.1%) | 0.157 | |||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 250(52%) | 52(82.5%) | 198(47.4%) | < 0.001 | 2.536 | 1.163–5.528 | 0.019 | 2.486 | 1.161–5.320 | 0.019 | 2.407 | 1.131–5.124 | 0.023 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 442(91.9%) | 63(100%) | 379(90.7%) | 0.005 | 1.550 | 0.001–1.555 | 0.998 | 1.680 | 0.012–1.869 | 0.998 | 1.110 | 0.015–1.015 | 0.998 |

| History of stroke | 28(5.8%) | 4(6.3%) | 24(5.7%) | 0.775 | |||||||||

| History of myocardial infarction | 100(20.8%) | 31(49.2%) | 69(16.5%) | < 0.001 | 2.796 | 1.384–5.649 | 0.004 | 2.312 | 1.170–4.569 | 0.016 | 2.099 | 1.073–4.103 | 0.030 |

| Heart failure | < 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.010 | 0.007 | |||||||||

| Preserved EF | 50(10.4%) | 11(17.5%) | 39(9.3%) | 1.170 | 0.458–2.987 | 0.743 | 1.457 | 0.591–3.592 | 0.414 | 1.489 | 0.611–3.631 | 0.381 | |

| Reduced EF | 50(10.4%) | 24(38.1%) | 26(6.2%) | 3.656 | 1.498–8.921 | 0.004 | 3.793 | 1.592–9.041 | 0.003 | 3.960 | 1.676–9.356 | 0.002 | |

| Chronic liver disease | 22(4.6%) | 1(1.6%) | 21(5.0%) | 0.337 | |||||||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 182(37.8%) | 40(63.5%) | 142(34%) | < 0.001 | 1.023 | 0.498–2.101 | 0.950 | 0.933 | 0.459–1.899 | 0.849 | 1.003 | 0.499–2.018 | 0.992 |

| Previously documented AF | 126(26.2%) | 19(30.2%) | 107(25.6%) | 0.443 | |||||||||

| Echo parameters | |||||||||||||

| LVEF (%) | 69.0,13.0 | 57.0,30.0 | 70.0,11.3 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Mitral E/e’ ratio | 11.1,5.0 | 12.0,7.0 | 11.0,5.0 | 0.005 | |||||||||

| LA diameter (cm) | 3.8,0.7 | 4.0,0.6 | 3.7,0.7 | < 0.001 | 1.152 | 0.694–1.912 | 0.583 | 1.185 | 0.718–1.955 | 0.507 | 1.310 | 0.799–2.148 | 0.285 |

| RV systolic function (s’, m/s) | 12.0,2.0 | 12.0,2.0 | 12.0,2.0 | < 0.001 | 0.818 | 0.658–1.018 | 0.072 | 0.814 | 0.662–1.001 | 0.051 | 0.814 | 0.662–1.000 | 0.050 |

| Drug prescribed at baseline | |||||||||||||

| Antiplatelets | 153(31.8%) | 46(73.0%) | 107(25.6%) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Anticoagulants | 122(25.4%) | 19(30.2%) | 103(24.6%) | 0.348 | |||||||||

| Beta blockers | 155(32.2%) | 41(65.1%) | 114(27.3%) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Amiodarone | 100(20.8%) | 25(39.7%) | 75(17.9%) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Dronedarone | 18(3.7%) | 2(3.2%) | 16(3.8%) | 1.0 | |||||||||

| Flecainide | 2(0.4%) | 0(0%) | 2(0.5%) | 1.0 | |||||||||

| Propafenone | 24(5%) | 3(4.8%) | 21(5.0%) | 1.0 | |||||||||

| Sotalol | 2(0.4%) | 1(1.6%) | 1(0.2%) | 0.245 | |||||||||

| Digoxin | 5(1%) | 4(6.3%) | 1(0.2%) | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Non-DHP CCBs | 19(4%) | 3(4.8%) | 16(3.8%) | 0.726 | |||||||||

| RAAS inhibitors | 194(40.4%) | 28(44.4%) | 166(39.8%) | 0.485 | |||||||||

| Diuretics | 70(14.6%) | 19(30.2%) | 51(12.2%) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Statins | 166(34.5%) | 28(44.4%) | 138(33.0%) | 0.075 | |||||||||

| Metformin | 79(16.4%) | 13(20.6%) | 66(15.8%) | 0.333 | |||||||||

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 5(1%) | 1(1.6%) | 4(1.0%) | 0.506 | |||||||||

| Follow-up duration | 39.9 ± 29.8 | 41.6 ± 26.4 | 39.7 ± 30.3 | 0.630 | |||||||||

| Follow-up times | 5.6 ± 4.2 | 5.5 ± 3.5 | 5.6 ± 4.3 | 0.790 | |||||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 5 min | 188(39.1%) | 43(68.3%) | 145(34.7%) | < 0.001 | 5.252 | 2.575–10.715 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 6 h | 115(23.9%) | 26(41.3%) | 89(21.3%) | 0.001 | 2.548 | 1.284–5.058 | 0.007 | ||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 24 h | 83(17.3%) | 17(27.0%) | 66(15.8%) | 0.028 | 1.825 | 0.874–3.809 | 0.109 | ||||||

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median, IQR or n (%).

AF atrial fibrillation, AHRE atrial high-rate episodes, BMI body mass index, EF ejection fraction, IQR interquartile range, LA left atrium, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, RV right ventricle, non-DHP CCBs non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, RAAS renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, SGLT2 sodium glucose co-transporters 2.

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis with time-dependent covariates for MACE predictors in patients without history of atrial fibrillation and with AHREs ≥ 5mins (Model A), ≥ 6hrs (Model B), ≥ 24hrs (Model C).

| Variable | History of atrial fibrillation (−) (N = 355) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) | P | Multivariable Cox regression |

||||||||||

| Yes (N = 44) | No (N = 311) | Model A | Model B | Model C | ||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | ||||

| Age (years) | 77.0,12.3 | 77.0,16.0 | 0.468 | |||||||||

| Gender | 0.115 | |||||||||||

| Male | 30(68.2%) | 173(55.6%) | ||||||||||

| Female | 14(31.8%) | 138(44.4%) | ||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4,2.8 | 24.6,3.3 | 0.297 | |||||||||

| Device | 0.929 | 0.998 | 0.424–2.352 | 0.996 | 0.838 | 0.365–1.920 | 0.675 | 0.707 | 0.311–1.606 | 0.408 | ||

| Metronic | 27(61.4%) | 193(62.1%) | ||||||||||

| BIOTRONIK | 17(38.6%) | 118(37.9%) | ||||||||||

| Primary indication | 0.229 | |||||||||||

| Sinus node dysfunction | 34(77.3%) | 200(64.3%) | ||||||||||

| Atrioventricular block | 10(22.7%) | 110(35.4%) | ||||||||||

| Other | 0(0%) | 1(0.3%) | ||||||||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 3.1 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| HAS-BLED | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 43(97.7%) | 285(91.6%) | 0.226 | |||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 37(84.1%) | 148(47.6%) | < 0.001 | 2.577 | 0.968–6.864 | 0.058 | 2.400 | 0.913–6.307 | 0.076 | 2.271 | 0.872–5.917 | 0.093 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 44(100%) | 277(89.1%) | 0.013 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 1.130 | 0.001–1.005 | 0.998 | ||||

| History of stroke | 2(4.5%) | 12(3.9%) | 0.688 | |||||||||

| History of myocardial infarction | 23(52.3%) | 49(15.8%) | < 0.001 | 2.087 | 0.852–5.113 | 0.107 | 1.805 | 0.742–4.394 | 0.193 | 1.671 | 0.701–3.984 | 0.246 |

| Heart failure | < 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.004 | ||||||||

| Preserved EF | 6(13.6%) | 22(7.1%) | 1.208 | 0.352–4.150 | 0.764 | 1.457 | 0.432–4.908 | 0.544 | 1.577 | 0.482–5.159 | 0.376 | |

| Reduced EF | 20(45.5%) | 20(6.4%) | 5.759 | 1.917–17.301 | 0.002 | 5.646 | 1.929–16.523 | 0.002 | 5.821 | 1.988–17.040 | < 0.001 | |

| Chronic liver disease | 0(0%) | 18(5.8%) | 0.145 | |||||||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 29(65.9%) | 104(33.4%) | < 0.001 | 0.920 | 0.375–2.261 | 0.856 | 0.836 | 0.335–2.082 | 0.700 | 0.975 | 0.403–2.358 | 0.975 |

| Echo parameters | ||||||||||||

| LVEF % | 55.0,34.0 | 70.0,13.0 | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Mitral E/e’ ratio | 12.0,6.0 | 11.1,5.0 | 0.044 | |||||||||

| LA diameter (cm) | 4.0,0.7 | 3.6,0.8 | < 0.001 | 1.502 | 0.765–2.951 | 0.238 | 1.557 | 0.791–3.064 | 0.200 | 1.779 | 0.902–3.507 | 0.096 |

| RV systolic function (s’, ms) | 11.5,2.0 | 12.0,2.0 | < 0.001 | 0.856 | 0.661–1.109 | 0.239 | 0.840 | 0.655–1.077 | 0.169 | 0.844 | 0.399–1.082 | 0.182 |

| Drug prescribed at baseline | ||||||||||||

| Antiplatelets | 36(81.8%) | 92(29.6%) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Anticoagulants | 5(11.4%) | 27(8.7%) | 0.561 | |||||||||

| Beta blockers | 26(59.1%) | 70(22.5%) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Amiodarone | 12(27.3%) | 32(10.3%) | 0.001 | |||||||||

| Dronedarone | 1(2.3%) | 4(1.3%) | 0.486 | |||||||||

| Flecainide | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | ||||||||||

| Propafenone | 1(2.3%) | 14(4.5%) | 0.705 | |||||||||

| Sotalol | 1(2.3%) | 1(0.3%) | 0.233 | |||||||||

| Digoxin | 4(9.1%) | 0(0%) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Non-DHP CCBs | 2(4.5%) | 10(3.2%) | 0.650 | |||||||||

| RAAS inhibitors | 22(50.0%) | 116(37.4%) | 0.109 | |||||||||

| Diuretics | 16(36.4%) | 41(13.2%) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Statins | 21(47.7%) | 100(32.2%) | 0.041 | |||||||||

| Metformin | 10(22.7%) | 47(15.1%) | 0.198 | |||||||||

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 1(2.3%) | 3(1.0%) | 0.412 | |||||||||

| Follow-up duration | 45.2 ± 27.5 | 41.7 ± 31.7 | 0.478 | |||||||||

| Follow-up times | 6.0 ± 3.8 | 5.8 ± 4.4 | 0.759 | |||||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 5 min | 25(56.8%) | 82(26.4%) | < 0.001 | 4.266 | 1.856–9.805 | 0.001 | ||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 6 h | 14(31.8%) | 41(13.2%) | 0.001 | 2.459 | 0.974–6.210 | 0.057 | ||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 24 h | 8(18.2%) | 29(9.3%) | 0.072 | 1.194 | 0.399–3.574 | 0.751 | ||||||

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median, IQR or n (%).

AF atrial fibrillation, AHRE atrial high-rate episodes, BMI body mass index, EF ejection fraction, IQR interquartile range, LA left atrium, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, RV right ventricle, non-DHP CCBs non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, RAAS renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, SGLT2 sodium glucose co-transporters 2.

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis with time-dependent covariates for MACE predictors in patients with history of atrial fibrillation and with AHREs ≥ 5 min (Model A), ≥ 6 h (Model B), ≥ 24 h (Model C).

| Variable | History of atrial fibrillation ( +) (N = 126) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major adverse cardiac events (MACE) | Univariate P valve |

Multivariate Cox regression | |||||||||||||

| Yes (N = 19) | No (N = 107) | Model A | Model B | Model C | |||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |||||||

| Age (years) | 75.0,11.0 | 74.0,13.0 | 0.733 | ||||||||||||

| Gender | 0.824 | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 8(42.1%) | 48(44.9%) | |||||||||||||

| Female | 11(57.9%) | 59(55.1%) | |||||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.8,4.0 | 24.2,2.6 | 0.542 | ||||||||||||

| Device | 0.201 | 2.363 | 0.510–10.945 | 0.272 | 1.578 | 0.384–6.479 | 0.526 | 1.355 | 0.340–5.405 | 0.667 | |||||

| Metronic | 13(68.4%) | 87(81.3%) | |||||||||||||

| BIOTRONIK | 6(31.6%) | 20(18.7%) | |||||||||||||

| Primary indication | 0.557 | ||||||||||||||

| Sinus node dysfunction | 16(84.2%) | 90(84.1%) | |||||||||||||

| Atrioventricular block | 3(15.8%) | 12(11.2%) | |||||||||||||

| Other | 0(0%) | 5(4.7%) | |||||||||||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 4.3 ± 0.9 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 0.015 | ||||||||||||

| HAS-BLED | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 19(100%) | 104(97.2%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 15(78.9%) | 50(46.7%) | 0.012 | 2.482 | 0.644–9.568 | 0.187 | 2.820 | 0.794–10.023 | 0.109 | 2.642 | 0.745–9.368 | 0.132 | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 19(100%) | 102(95.3%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| History of stroke | 2(10.5%) | 12(11.2%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| History of myocardial infarction | 8(42.1%) | 20(18.7%) | 0.024 | 3.635 | 0.987–13.384 | 0.052 | 3.099 | 0.941–10.207 | 0.063 | 3.020 | 0.917–9.945 | 0.069 | |||

| Heart failure | 0.026 | 0.955 | 0.708 | 0.549 | |||||||||||

| Preserved EF | 5(26.3%) | 17(15.9%) | 0.928 | 0.197–4.362 | 0.924 | 1.080 | 0.265–4.397 | 0.914 | 1.065 | 0.262–4.323 | 0.930 | ||||

| Reduced EF | 4(21.1%) | 6(5.6%) | 1.271 | 0.188–8.579 | 0.805 | 2.125 | 0.351–12.866 | 0.412 | 2.712 | 0.441–16.664 | 0.281 | ||||

| Chronic liver disease | 1(5.3%) | 3(2.8%) | 0.484 | ||||||||||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 11(57.9%) | 38(35.5%) | 0.065 | ||||||||||||

| Echo parameters | |||||||||||||||

| LVEF % | 60.0,16.0 | 70.0,10.0 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Mitral E/e’ ratio | 13.0,10.0 | 10.6,4.7 | 0.035 | 1.090 | 0.940–1.266 | 0.255 | 1.069 | 0.930–1.229 | 0.348 | 1.084 | 0.944–1.245 | 0.252 | |||

| LA diameter (cm) | 4.0,0.5 | 3.9,0.7 | 0.157 | ||||||||||||

| RV systolic function (s’, m/s) | 12.0,3.0 | 12.0,2.0 | 0.058 | ||||||||||||

| Drug prescribed at baseline | |||||||||||||||

| Antiplatelets | 10(52.6%) | 15(14.0%) | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Anticoagulants | 14(73.7%) | 76(71.0%) | 0.813 | ||||||||||||

| Beta blockers | 15(78.9%) | 44(41.1%) | 0.003 | ||||||||||||

| Amiodarone | 13(68.4%) | 43(40.2%) | 0.022 | ||||||||||||

| Dronedarone | 1(5.3%) | 12(11.2%) | 0.690 | ||||||||||||

| Flecainide | 0(0%) | 2(1.9%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Propafenone | 2(10.5%) | 7(6.5%) | 0.624 | ||||||||||||

| Sotalol | 0(0%) | (0%) | |||||||||||||

| Digoxin | 0(0%) | 1(0.9%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Non-DHP CCBs | 1(5.3%) | 6(5.6%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| RAAS inhibitors | 6(31.6%) | 50(46.7%) | 0.221 | ||||||||||||

| Diuretics | 3(15.8%) | 10(9.3%) | 0.414 | ||||||||||||

| Statins | 7(36.8%) | 38(35.5%) | 0.911 | ||||||||||||

| Metformin | 3(15.8%) | 19(17.8%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 0(0%) | 1(0.9%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Follow duration | 33.4 ± 22.4 | 33.8 ± 25.1 | 0.949 | ||||||||||||

| Follow times | 4.4 ± 2.5 | 5.3 ± 4.0 | 0.327 | ||||||||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 5 min | 18(94.7%) | 63(58.9%) | 0.002 | 18.383 | 2.006–168.428 | 0.010 | |||||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 6 h | 12(63.2%) | 48(44.9%) | 0.141 | 2.345 | 0.715–7.696 | 0.160 | |||||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 24 h | 9(47.4%) | 37(34.6%) | 0.286 | 2.129 | 0.677–6.692 | 0.196 | |||||||||

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median, IQR or n (%).

AF atrial fibrillation, AHRE atrial high-rate episodes, BMI body mass index, EF ejection fraction, IQR interquartile range, LA left atrium, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, RV right ventricle, non-DHP CCBs non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, RAAS renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, SGLT2 sodium glucose co-transporters 2.

Ethics statement

The study protocol has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Cheng Kung University Hospital. (B-ER-108-278).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of National Cheng Kung University Hospital and was conducted according to the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization for Good Clinical Practice. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Consent for publication

All patients provided signed informed consent before enrollment.

Results

Between January 1, 2014 and August 31, 2019, a total of 498 patients receiving dual chamber permanent pacemaker at our hospital were initially recruited. Seventeen patients were excluded due to loss of follow-up, inadequate or missing data and not providing informed consent. Therefore, the data of 481 patients were finally included as the analytic sample for this retrospective study.

The mean follow-up period was 39.9 ± 29.8 months after the implantation of dual chamber permanent pacemakers. Table 1 shows baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients based on the occurrence of AHRE ≥ 5 min, ≥ 6 h or ≥ 24 h. Mean age was 75.3 ± 10.7 years and 46.2% were women. The most common indication for dual chamber permanent pacemaker implantation (Table 1) was sick sinus syndrome (70.7%), followed by atrioventricular block (28.1%). High percentages of hypertension (93.8%) and hyperlipidemia (91.9%) suggested a relatively high risk of MACE for the entire study cohort. During follow-up, 188 patients developed AHRE ≥ 5 min, 115 patients developed AHRE ≥ 6 h, and 83 patients developed AHRE ≥ 24 h. Patients with AHRE had significantly lower left ventricular ejection fraction, larger left atrial (LA) diameters and history of documented AF. Components, time to MACE, incidence rates and distribution of MACE are reported in Table 2. The whole follow-up duration represented 1600.25 patient-years of observation, and the total number of MACE was 92 (IR 5.75%/year, 95% CI 3.88–5.85). The proportion of MACE for each separate AHRE duration decreased as AHRE duration increased. Patients with a history of MI at baseline (17.80%/year 95% CI 10.23–22.11) had a higher incidence of MACE than those without previous MI (IR 3.77%/year 95% CI 3.01–4.22; p = 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the overall study group.

| Variables | All patients (n = 481) | AHREs ≥ 5 min | P | AHREs ≥ 6 h | P | AHREs ≥ 24 h | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 188) | No (N = 293) | Yes (N = 115) | No (N = 366) | Yes (N = 83) | No (N = 398) | ||||||

| Age (years) | 77.0,14.0 | 76.0,15.0 | 77.0,15.0 | 0.318 | 76.0,14.0 | 77.0,15.0 | 0.376 | 77.0,14.0 | 76.0,15.3 | 0.880 | |

| Gender | 0.204 | 0.129 | 0.199 | ||||||||

| Male | 259(53.8%) | 108(57.4%) | 151(51.5%) | 69(60.0%) | 190(51.9%) | 50(60.2%) | 209(52.5%) | ||||

| Female | 222(46.2%) | 80(42.6%) | 142(48.5%) | 46(40.0%) | 176(48.1%) | 33(39.8%) | 189(47.5%) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.5,2.9 | 24.3,3.3 | 24.6,2.6 | 0.132 | 24.1,3.1 | 24.6,2.7 | 0.083 | 24.1,3.7 | 24.6,2.8 | 0.077 | |

| Device | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Metronic | 320(66.5%) | 157(83.5%) | 163(55.6%) | 102(88.7%) | 218(59.6%) | 75(90.4%) | 245(61.6%) | ||||

| BIOTRONIK | 161(33.5%) | 31(16.5%) | 130(44.4%) | 13(11.3%) | 148(40.4%) | 8(9.6%) | 153(38.4%) | ||||

| Primary indication | 0.335 | 0.165 | 0.045 | ||||||||

| Sinus node dysfunction | 340(70.7%) | 139(73.9%) | 201(68.6%) | 85(73.9%) | 255(69.7%) | 62(74.7%) | 278(69.8%) | ||||

| Atrioventricular block | 135(28.1%) | 46(24.5%) | 89(30.4%) | 27(23.5%) | 108(29.5%) | 18(21.7%) | 117(29.4%) | ||||

| Other | 6(1.2%) | 3(1.6%) | 3(1.0%) | 3(2.6%) | 3(0.8%) | 3(3.6%) | 3(0.8%) | ||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 1.3 | 3.2 ± 1.3 | 0.109 | 3.5 ± 1.4 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 0.194 | 3.5 ± 1.4 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 0.191 | |

| HAS-BLED | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 2.2 ± 1.2 | 0.069 | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 0.08 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 0.370 | |

| Hypertension | 451(93.8%) | 182(96.8%) | 269(91.8%) | 0.027 | 110(95.7%) | 341(93.2%) | 0.337 | 79(95.2%) | 372(93.5%) | 0.557 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 250(52%) | 99(52.7%) | 151(51.5%) | 0.810 | 61(53.0%) | 189(51.6%) | 0.793 | 44(53.0%) | 206(51.8%) | 0.835 | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 442(91.9%) | 181(96.3%) | 261(89.1%) | 0.005 | 110(95.7%) | 332(90.7%) | 0.09 | 79(95.2%) | 363(91.2%) | 0.228 | |

| History of stroke | 28(5.8%) | 14(7.4%) | 14(4.8%) | 0.223 | 5(4.3%) | 23(6.3) | 0.439 | 5(6.0%) | 23(5.8%) | 0.931 | |

| History of myocardial infarction | 100(20.8%) | 38(20.2%) | 62(21.2%) | 0.803 | 24(20.9%) | 76(20.8%) | 0.981 | 19(22.9%) | 81(20.4%) | 0.604 | |

| Heart failure | 0.003 | 0.011 | 0.013 | ||||||||

| Preserved EF | 50(10.4%) | 29(15.4%) | 21(7.2%) | 19(16.5%) | 31(8.5%) | 16(19.3%) | 34(8.5%) | ||||

| Reduced EF | 50(10.4%) | 24(12.8%) | 26(8.9%) | 16(13.9%) | 34(9.3%) | 9(10.8%) | 41(10.3%) | ||||

| Chronic liver disease | 22(4.6%) | 8(4.3%) | 14(4.8%) | 0.789 | 7(6.1%) | 15(4.1%) | 0.373 | 5(6.0%) | 17(4.3%) | 0.487 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 182(37.8%) | 79(42.0%) | 103(35.2%) | 0.130 | 57(49.6%) | 125(34.2%) | 0.003 | 40(48.2%) | 142(35.7%) | 0.032 | |

| Previously documented Af | 126(26.2%) | 81(43.1%) | 45(15.4%) | < 0.001 | 60(52.2%) | 66(18.0%) | < 0.001 | 46(55.4%) | 80(20.1%) | < 0.001 | |

| Echo parameters | |||||||||||

| LVEF (%) | 69.0,13.0 | 67.0,15.0 | 70.0,13.0 | 0.002 | 66.0,14.0 | 70.0,13.0 | < 0.001 | 66.0,12.0 | 70.0,12.6 | 0.008 | |

| Mitral E/e’ ratio | 11.1,5.0 | 11.6,5.0 | 11.0,5.1 | 0.474 | 12.0,6.0 | 11.0,5.0 | 0.189 | 12.0,5.0 | 11.0,5.0 | 0.174 | |

| LA diameter (cm) | 3.8,0.7 | 3.9,0.6 | 3.7,0.8 | 0.002 | 3.9,0.8 | 3.7,0.7 | 0.002 | 3.9,0.8 | 3.7,0.7 | 0.005 | |

| RV systolic function (s’, m/s) | 12.0,2.0 | 12.0,2.0 | 12.0,2.0 | 0.356 | 12.0,2.0 | 12.0,2.0 | 0.523 | 12.0,2.0 | 12.0,2.0 | 0.393 | |

| Drug prescribed at baseline | |||||||||||

| Antiplatelets | 153(31.8%) | 58(30.9%) | 95(32.4%) | 0.718 | 37(32.2%) | 116(31.7%) | 0.923 | 24(28.9%) | 129(32.4%) | 0.534 | |

| Anticoagulants | 122(25.4%) | 81(43.1%) | 41(14.0%) | < 0.001 | 53(46.1%) | 69(18.9%) | < 0.001 | 42(50.6%) | 80(20.1%) | < 0.001 | |

| Beta blockers | 155(32.2%) | 81(43.1%) | 74(25.3%) | < 0.001 | 57(49.6%) | 98(26.8%) | < 0.001 | 44(53.0%) | 111(27.9%) | < 0.001 | |

| Amiodarone | 100(20.8%) | 60(31.9%) | 40(13.7%) | < 0.001 | 42(36.5%) | 58(15.8%) | < 0.001 | 33(39.8%) | 67(17.8%) | < 0.001 | |

| Dronedarone | 18(3.7%) | 14(7.4%) | 4(1.4%) | 0.001 | 12(10.4%) | 6(1.6%) | < 0.001 | 8(9.6%) | 10(2.5%) | 0.002 | |

| Flecainide | 2(0.4%) | 2(1.1%) | 0(0%) | 0.152 | 2(1.7%) | 0(0%) | 0.057 | 2(2.4%) | 0(0%) | 0.029 | |

| Propafenone | 24(5%) | 12(6.4%) | 12(4.1%) | 0.261 | 6(5.2%) | 18(4.9%) | 0.898 | 5(6.0%) | 19(4.8%) | 0.634 | |

| Sotalol | 2(0.4%) | 2(1.1%) | 0(0%) | 0.152 | 2(1.7) | 0(0%) | 0.057 | 1(1.2%) | 1(0.3%) | 0.316 | |

| Digoxin | 5(1%) | 2(1.1%) | 3(1.0%) | 1.000 | 0(0%) | 5(1.4%) | 0.597 | 0(0%) | 5(1.3%) | 0.593 | |

| Non-DHP CCBs | 19(4%) | 11(5.9%) | 8(2.7%) | 0.086 | 4(3.5%) | 15(4.1%) | 1.000 | 4(4.8%) | 15(3.8%) | 0.755 | |

| RAAS inhibitors | 194(40.4%) | 74(39.4%) | 120(41.1%) | 0.705 | 41(35.7%) | 153(41.9%) | 0.232 | 28(33.7%) | 166(41.8%) | 0.179 | |

| Diuretics | 70(14.6%) | 26(13.8%) | 44(15.0%) | 0.791 | 20(17.4%) | 50(13.7%) | 0.322 | 16(19.3%) | 54(13.6%) | 0.180 | |

| Statins | 166(34.5%) | 62(33.0%) | 104(35.5%) | 0.571 | 37(32.2%) | 129(35.2%) | 0.546 | 28(33.7%) | 138(34.7%) | 0.870 | |

| Metformin | 79(16.4%) | 24(12.8%) | 55(18.8%) | 0.083 | 12(10.4%) | 67(18.3%) | 0.047 | 9(10.8%) | 70(17.6%) | 0.131 | |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 5(1%) | 2(1.1%) | 3(1.0%) | 1.000 | 1(0.9%) | 4(1.1%) | 1.000 | 1(1.2%) | 4(1.0%) | 1.000 | |

| Follow-up duration | 39.9 ± 29.8 | 40.8 ± 29.7 | 39.3 ± 30.0 | 0.588 | 39.1 ± 28.2 | 40.2 ± 30.3 | 0.736 | 36.6 ± 25.7 | 40.6 ± 30.6 | 0.262 | |

| Follow-up times | 5.6 ± 4.2 | 5.8 ± 4.5 | 5.5 ± 4.1 | 0.519 | 5.7 ± 4.4 | 5.6 ± 4.2 | 0.917 | 5.1 ± 3.3 | 5.7 ± 4.4 | 0.239 | |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median, IQR or n (%).

AF atrial fibrillation, AHRE atrial high-rate episodes, BMI body mass index, EF ejection fraction, IQR interquartile range, LA left atrium, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, RV right ventricle, non-DHP CCBs non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, RAAS renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, SGLT2 sodium glucose co-transporters 2.

Table 2.

Type and incidence of MACEs in the whole cohort.

| Types of MACEs | Number | Incidence rate (100 patient-years) | CI 95% | Time to event (months) | Age (years) | Gender (female) | History of Af | History of MI | AHREs > 5mins | AHREs > 6mins | AHREs > 6hrs | AHREs > 12hrs | AHREs > 24hrs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEMI | 2 | 0.125 | (0.02–0.34) | 30.5 ± 24.7 (13–48) | 66.5 ± 2.1 | 0(0%) | 2(100%) | 1(50%) | 2(100%) | 2(100%) | 2(100%) | 2(100%) | 2(100%) |

| NSTEMI | 23 | 1.437 | (0.78–1.77) | 29.9 ± 26.8 (2–99) | 78.7 ± 9.2 | 11(47.8%) | 8(34.5%) | 15(65.2%) | 16(69.6%) | 16(69.6%) | 9(39.1%) | 7(30.4%) | 7(30.4%) |

| Unstable angina | 35 | 2.187 | (1.29–2.51) | 26.8 ± 24.4 (2–106) | 76.2 ± 8.0 | 11(31.4%) | 9(25.7%) | 19(54.3%) | 23(65.7%) | 23(65.7%) | 13(37.1%) | 11(31.4%) | 6(17.1%) |

| Deteriorated heart failure | 23 | 1.437 | (0.78–1.77) | 23.4 ± 17.5 (2–82) | 75.7 ± 8.5 | 6(26.1%) | 9(39.1%) | 14(60.9%) | 15(65.2%) | 15(65.2%) | 10(43.5%) | 9(39.1%) | 8(34.8%) |

| Cardiovascular hospitalization | 6 | 0.375 | (0.13–0.65) | 25.8 ± 24.2 (2–78) | 73.8 ± 12.7 | 3(37.5%) | 3(50%) | 5(62.5%) | 4(66.7%) | 4(66.7%) | 3(50%) | 3(37.5%) | 2(33.3%) |

| Cardiac death | 3 | 0.187 | (0.04–0.43) | 25.7 ± 19.2 (25–27) | 76.5 ± 9.2 | 0(0%) | 3(100%) | 2(66.7%) | 2(66.7%) | 2(66.7%) | 1(33.3%) | 1(33.3%) | 0(0%) |

| Total event | 92 | 5.749 | (3.88–5.85) |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%).

Af atrial fibrillation, AHREs atrial high-rate episodes, CI confidence intervals, MACEs major adverse cardiac events, MI myocardial infarction, NSTEMI non ST-elevation myocardial infarction, STEMI ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

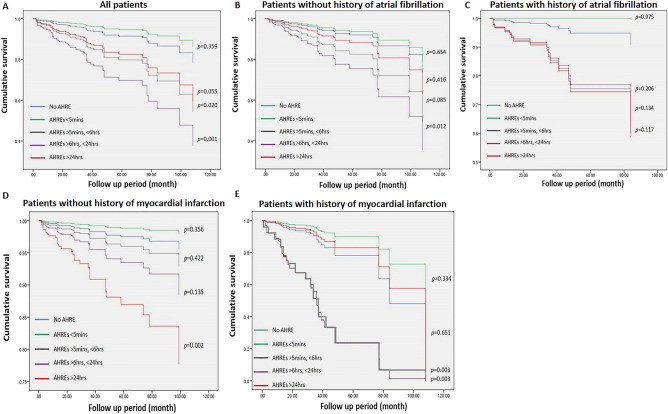

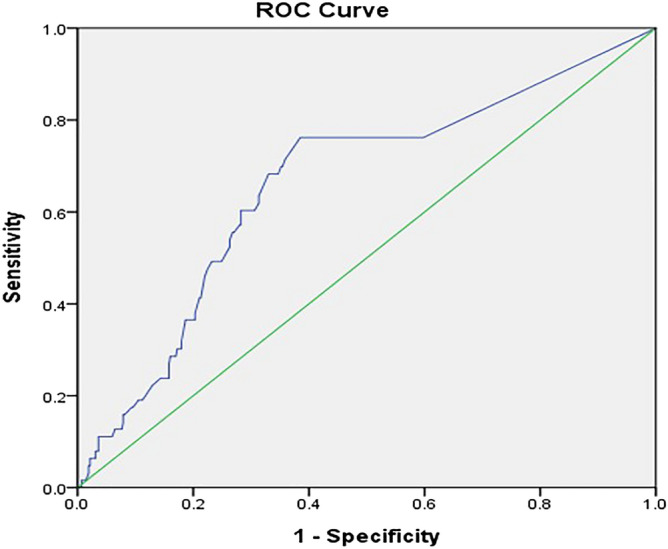

ROC-AUC determination of AHRE cutoff values associated with future MACE

The optimal AHRE cutoff value for association with future MACE was determined to be 5-min (sensitivity, 68.3%; specificity, 65.3%; AUC, 0.662; 95% CI, 0.588–0.736; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Receiver-operating characteristic curve analysis of atrial high-rate episodes (minutes) in patients with dual chamber permanent pacemakers with subsequent MACE Atrial high rate episodes (minutes): cutoff value, 5-min; sensitivity, 68.3%; specificity, 65.3%; AUC, 0.662; 95% CI, 0.588–0.736; p < 0.001.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis of associations between duration of AHRE and MACE in all patients

Univariable analysis revealed that the CHA2DS2-VASc score and HAS-BLED score for stroke risk; diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, history of MI, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease; LV ejection fraction, mitral E/e ratio; LA diameter; RV systolic function, and AHRE duration ≥ 5 min, ≥ 6 h and ≥ 24 h; were significantly associated with MACE occurrence in all patients (Table 3). Multivariable Cox regression analysis demonstrated that AHRE ≥ 5 min (HR 5.252, 95% CI 2.575–10.715, p < 0.001) in model A, and AHRE ≥ 6 h (HR 2.548, 95% CI 1.284–5.058, p = 0.007) in model B were independently associated with MACE. However, AHRE ≥ 24 h in model C was not significantly associated with MACE.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis of associations between AHRE duration and MACE in patients with or without history of AF

In the subgroup of patients with or without history of atrial fibrillation, multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that AHREs ≥ 5 min were significantly associated with MACEs in patients without history of AF (HR 4.266, 95% CI 1.856–9.805, p = 0.001) as same as heart failure reduced ejection fraction (HR 5.729, 95% CI 1.917–17.301, P = 0.002) (Table 4). For patients with history of AF, only AHREs ≥ 5 min (HR 18.383, 95% CI 2.006–168.428, p = 0.010) has significant difference (Table 5). Both patients demonstrated that AHREs ≥ 6 h and AHREs ≥ 24 h had no significant difference with MACEs.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis of associations between duration of AHRE and MACEs in patients with or without history of MI

Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that AHRE ≥ 5 min (HR 4.086, 95% CI 1.638–10.192, p = 0.003), AHRE ≥ 6 h (HR 2.756, 95% CI 1.166–6.517, p = 0.021) and AHRE ≥ 24 h (HR 3.348, 95% CI 1.359–8.243, p = 0.009) were all significantly associated with MACE in patients without history of MI (Table 6), but only AHRE ≥ 5 min (HR 10.370, 95% CI 2.860–37.595, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with MACE in patients with history of MI (Table 7). Other risk factor such as heart failure reduced ejection was also independently associated with MACE in patients with all three AHRE durations without history of MI.

Table 6.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis with time-dependent covariates for MACE predictors in patients without history of myocardial infarction and with AHREs ≥ 5 min (Model A), ≥ 6 h (Model B), ≥ 24 h (Model C).

| Variable | History of myocardial infarction (−) (N = 381) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mace major adverse cardiac events | Univariate P valve |

Multivariate Cox regression | ||||||||||

| Yes (N = 32) | No (N = 349) | Model A | Model B | Model C | ||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | ||||

| Age (years) | 77.0,11.3 | 76.0,16.0 | 0.620 | |||||||||

| Gender | 0.236 | |||||||||||

| Male | 20(62.5%) | 180(51.6%) | ||||||||||

| Female | 12(37.5%) | 169(48.4%) | ||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.5,2.5 | 24.5,2.8 | 0.184 | |||||||||

| Device | 0.199 | 0.571 | 0.201–1.624 | 0.293 | 0.530 | 0.190–1.479 | 0.225 | 0.473 | 0.169–1.324 | 0.154 | ||

| Metronic | 25(78.1%) | 234(67.0%) | ||||||||||

| BIOTRONIK | 7(21.9%) | 115(33.0%) | ||||||||||

| Primary indication | 0.145 | |||||||||||

| Sinus node dysfunction | 27(84.4%) | 237(67.9%) | ||||||||||

| Atrioventricular block | 5(15.6%) | 107(30.7%) | ||||||||||

| Other | 0(0%) | 5(1.4%) | ||||||||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3.9 ± 1.0 | 3.0 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| HAS-BLED | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 1.0 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 32(100%) | 321(92.0%) | 0.151 | |||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 24(75.0%) | 146(41.8%) | < 0.001 | 3.486 | 1.401–8.672 | 0.007 | 3.468 | 1.402–8.579 | 0.007 | 3.451 | 1.392–8.553 | 0.007 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 32(100%) | 310(88.8%) | 0.060 | |||||||||

| History of stroke | 4(12.5%) | 19(5.4%) | 0.116 | |||||||||

| Heart failure | < 0.001 | 0.045 | 0.020 | 0.007 | ||||||||

| Preserved EF | 2(6.3%) | 24(6.9%) | 0.475 | 0.093–2.418 | 0.370 | 0.621 | 0.125–3.075 | 0.559 | 0.576 | 0.114–2.903 | 0.504 | |

| Reduced EF | 10(31.3%) | 11(3.2%) | 3.475 | 1.061–11.379 | 0.040 | 4.578 | 1.428–14.684 | 0.011 | 5.399 | 1.692–17.223 | 0.004 | |

| Chronic liver disease | 1(3.1%) | 16(4.6%) | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Previously documented Af | 11(34.4%) | 87(24.9%) | 0.242 | |||||||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 16(50.0%) | 100(28.7%) | 0.012 | 1.162 | 0.484–2.788 | 0.737 | 1.060 | 0.436–2.578 | 0.898 | 1.135 | 0.474–2.715 | 0.776 |

| Echo parameters | ||||||||||||

| LVEF % | 64.0,28.5 | 70.0,11.0 | 0.010 | |||||||||

| Mitral E/e’ ratio | 12.0,6.2 | 11.0,4.4 | 0.075 | |||||||||

| LA diameter (cm) | 4.0,0.7 | 3.6,0.8 | 0.002 | 1.229 | 0.665–2.271 | 0.511 | 1.291 | 0.702–2.373 | 0.411 | |||

| RV systolic function (s’, ms) | 12.0,2.0 | 13.0,2.0 | < 0.001 | 0.695 | 0.509–0.948 | 0.022 | 0.699 | 0.516–0.947 | 0.021 | |||

| Drug prescribed at baseline | ||||||||||||

| Antiplatelets | 23(71.9%) | 62(17.8%) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Anticoagulants | 12(37.5%) | 80(22.9%) | 0.065 | |||||||||

| Beta blockers | 18(56.3%) | 80(22.9%) | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Amiodarone | 11(34.4%) | 55(15.8%) | 0.008 | |||||||||

| Dronedarone | 0(0%) | 13(3.7%) | 0.613 | |||||||||

| Flecainide | 0(0%) | 1(0.3%) | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Propafenone | 3(9.4%) | 21(6.0%) | 0.441 | |||||||||

| Sotalol | 1(3.1%) | 0(0%) | 0.084 | |||||||||

| Digoxin | 2(6.3%) | 1(0.3%) | 0.019 | |||||||||

| Non-DHP CCBs | 3(9.4%) | 14(4.0%) | 0.163 | |||||||||

| RAAS inhibitors | 11(34.4%) | 128(36.8%) | 0.787 | |||||||||

| Diuretics | 8(25.0%) | 33(9.5%) | 0.007 | |||||||||

| Statins | 10(31.3) | 98(28.1%) | 0.703 | |||||||||

| Metformin | 5(15.6%) | 55(15.8%) | 0.984 | |||||||||

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 0(0%) | 2(0.6%) | 1.000 | |||||||||

| Follow-up duration | 40.2 ± 27.3 | 41.9 ± 31.4 | 0.783 | |||||||||

| Follow-up times | 5.9 ± 3.9 | 6.0 ± 4.9 | 0.923 | |||||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 5 min | 24(75.0%) | 126(36.1%) | < 0.001 | 4.086 | 1.638–10.192 | 0.003 | ||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 6 h | 16(50.0%) | 75(21.5%) | < 0.001 | 2.756 | 1.166–6.517 | 0.021 | ||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 24 h | 11(34.4%) | 53(15.2%) | 0.005 | 3.348 | 1.359–8.243 | 0.009 | ||||||

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median, IQR or n (%).

AF atrial fibrillation, AHRE atrial high-rate episodes, BMI body mass index, EF ejection fraction, IQR interquartile range, LA left atrium, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, RV right ventricle, non-DHP CCBs non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, RAAS renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, SGLT2 sodium glucose co-transporters 2.

Table 7.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis with time-dependent covariates for MACE predictors in patients with history of myocardial infarction and with AHREs ≥ 5 min (Model A), ≥ 6 h (Model B), ≥ 24 h (Model C).

| Variable | History of myocardial infarction ( +) (N = 100) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mace major adverse cardiac events | Univariate P valve |

Multivariate Cox regression | |||||||||||||

| Yes (N = 31) | No (N = 69) | Model A | Model B | Model C | |||||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |||||||

| Age (years) | 78.0,14.0 | 78.0,10.0 | 0.887 | ||||||||||||

| Gender | 0.899 | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 18(58.1%) | 41(59.4%) | |||||||||||||

| Female | 13(41.9%) | 28(40.6%) | |||||||||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.8,2.6 | 23.9,3.5 | 0.425 | ||||||||||||

| Device | 0.083 | 4.881 | 1.346–17.695 | 0.016 | 2.357 | 0.834–6.663 | 0.106 | 1.903 | 0.669–5.413 | 0.228 | |||||

| Metronic | 15(48.4%) | 46(66.7%) | |||||||||||||

| BIOTRONIK | 16(51.6%) | 23(33.3%) | |||||||||||||

| Primary indication | 0.733 | ||||||||||||||

| Sinus node dysfunction | 23(74.2%) | 53(76.8%) | |||||||||||||

| Atrioventricular block | 8(25.8%) | 15(21.7%) | |||||||||||||

| Other | 0(0%) | 1(1.4%) | |||||||||||||

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 0.029 | ||||||||||||

| HAS-BLED | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 0.268 | ||||||||||||

| Hypertension | 30(96.8%) | 68%(98.6%) | 0.526 | ||||||||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 28(90.3%) | 52(75.4%) | 0.108 | ||||||||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 31(100%) | 69(100%) | |||||||||||||

| History of stroke | 0(0%) | 5(7.2%) | 0.320 | ||||||||||||

| Heart failure | 0.012 | 0.033 | 0.054 | 0.035 | |||||||||||

| Preserved EF | 9(29.0%) | 15(21.7%) | 2.728 | 0.756–9.845 | 0.125 | 2.832 | 0.855–9.381 | 0.088 | 3.395 | 1.017–11.336 | 0.047 | ||||

| Reduced EF | 14(45.2%) | 15(21.7%) | 5.143 | 1.477–17.901 | 0.010 | 3.565 | 1.192–10.660 | 0.023 | 3.833 | 1.268–11.585 | 0.017 | ||||

| Chronic liver disease | 0(0%) | 5(7.2%) | 0.320 | ||||||||||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 24(77.4%) | 42(60.9%) | 0.106 | ||||||||||||

| Previously documented Af | 8(25.8%) | 20(29.0%) | 0.743 | ||||||||||||

| Echo parameters | |||||||||||||||

| LVEF % | 52.0,27.0 | 65.0,21.0 | 0.012 | ||||||||||||

| Mitral E/e’ ratio | 13.0,10.0 | 13.0,7.0 | 0.687 | ||||||||||||

| LA diameter (cm) | 4.0,0.4 | 4.0,0.7 | 0.599 | ||||||||||||

| RV systolic function (s’, m/s) | 12.0,2.0 | 12.0,3.0 | 0.055 | ||||||||||||

| Drug prescribed at baseline | |||||||||||||||

| Antiplatelets | 23(74.2%) | 45(65.2%) | 0.373 | ||||||||||||

| Anticoagulants | 7(22.6%) | 23(33.3%) | 0.278 | ||||||||||||

| Beta blockers | 23(74.2%) | 34(49.3%) | 0.020 | ||||||||||||

| Amiodarone | 14(45.2%) | 20(29.0%) | 0.114 | ||||||||||||

| Dronedarone | 2(6.5%) | 3(4.3%) | 0.644 | ||||||||||||

| Flecainide | 0(0%) | 1(1.4%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Propafenone | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | |||||||||||||

| Sotalol | 0(0%) | 1(1.4%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Digoxin | 2(6.5%) | 0(0%) | 0.094 | ||||||||||||

| Non-DHP CCBs | 0(0%) | 2(2.9%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| RAAS inhibitors | 17(54.8%) | 38(55.1%) | 0.983 | ||||||||||||

| Diuretics | 11(35.5%) | 18(26.1%) | 0.338 | ||||||||||||

| Statins | 18(58.1%) | 40(58.0%) | 0.993 | ||||||||||||

| Metformin | 8(25.8%) | 11(15.9%) | 0.245 | ||||||||||||

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 1(3.2%) | 2(2.9%) | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| Follow duration | 43.0 ± 25.9 | 28.6 ± 21.2 | 0.004 | ||||||||||||

| Follow times | 5.1 ± 3.1 | 4.0 ± 3.0 | 0.105 | ||||||||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 5 min | 19(61.3%) | 19(27.5%) | 0.001 | 10.370 | 2.860–37.595 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 6 h | 10(32.3%) | 14(20.3%) | 0.195 | 2.146 | 0.717–6.419 | 0.172 | |||||||||

| AHRE duration ≥ 24 h | 6(19.4%) | 13(18.8%) | 0.952 | 0.966 | 0.274–3.405 | 0.958 | |||||||||

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median, IQR or n (%).

AF atrial fibrillation, AHRE atrial high-rate episodes, BMI body mass index, EF ejection fraction, IQR interquartile range, LA left atrium, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, RV right ventricle, non-DHP CCBs non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, RAAS renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, SGLT2 sodium glucose co-transporters 2.

Freedom from MACE

We divided the duration of AHREs into five groups. No AHRE, AHRE < 5 min, AHRE ≥ 5minutes and < 6 h, AHRE ≥ 6 h and < 24 h, and AHRE ≥ 24 h for all patients and with history of AF, history of MI or not. Cox regression survival analysis of all patients showed that only AHRE ≥ 5 min and < 6 h were significantly different compared with patients with no AHRE (Fig. 2). No significant differences were found between patients with no AHRE and any specific duration of AHRE in patients with history of AF. For patients without history of AF, only those with AHRE ≥ 6 h and < 24 h showed significant differences between AHRE duration and MACE occurrence. For patients without history of MI, only AHRE > 24 h had significant differences between AHRE duration and MACE occurrence. In patients with history of MI, AHRE ≥ 5 min and < 6 h, AHRE ≥ 6 h and < 24 h had significant differences between AHRE duration and occurrence of MACE.

Figure 2.

Cox regression event-free survival curves from primary endpoint at 39.9 ± 29.8 months of follow-up based on five subgroups. (A) All patients. (B) Patients without history of AF. (C) Patients with history of AF. (D) Patients without history of MI. E: Patients with history of MI. (AF atrial fibrillation, MI myocardial infarction).

Discussion

The present ‘real world’ cohort study of the associations between different cutoff durations of AHRE and the incidence rates of MACE in patients with dual chamber permanent pacemakers with or without history of AF or MI revealed that (1) almost 40% of patients receiving dual-chamber pacemakers have device-detected AHRE; (2) hypertension, hyperlipidemia, heart failure, history of AF, chronic kidney disease, LA diameter, and AHRE duration are all independent predictors of incident MACE; and (3) although patients with dual chamber pacemakers who develop AHRE are at increased risk of MACE, patients with history of AF or history of MI and the longest AHRE duration also may have higher risk of MACE.

Results of previous studies have demonstrated that AHRE significantly increases risk for MACE4 and heart failure10, which depends upon the AHRE burden and duration in individual patients. However, in the present study, no linear relationship was found between duration of AHRE and development of MACE. Although AHRE ≥ 5 min and ≥ 6 h were independently associated with MACE, AHRE ≥ 24 h was not. However, in a study with a similar objective, Pastori et al.4 found that patients implanted with CIEDs who develop AHRE had a significantly elevated risk of MACE, and that the incidence rate of MACE occurring after AHRE onset was higher in patients with AHRE ≥ 24 h. Although this may correspond with our suggestion that patients with the longest duration of AHRE may be at greater risk of MACE, we did not show this definitively, most likely due to our smaller sample and different definition of MACE.

Results of Pastori et al.4 agreed with our results showing that AHRE ≥ 5 min, diabetes and heart failure were independent predictors of MACE. In the present study, we also found that hypertension, hyperlipidemia, history of AF, chronic kidney disease, and increased LA diameter were all significantly associated with the occurrence of AHRE. We also found that patients with MEDTRONIC devices have more frequent occurrence of AHRE than those with BIOTRONIK devices (p < 0.05), which may be due to different default settings for detecting AHRE.

In patients with implantable devices and with no history of AF, device‐detected AHRE can predict long‐term mortality outcomes11, and are known to be associated with increased risk of clinical AF, stroke, and thromboembolic events12. In the present study, we found that in patients with history of MI, only those with AHRE ≥ 5 min were independently associated with MACE, and for those without history of MI, AHRE ≥ 5 min, ≥ 6 h and ≥ 24 h were all independently associated with MACE. These results suggest that the cutoff value of AHRE may be lower in patients with history of MI than in patients without history of MI, even though the ROC-AUC analysis showed that the optimal cut-off was 5 min.

Three proposed mechanisms of MACE in patients with AF included: (1) both atherosclerosis and inflammatory process yield a pro-thrombotic state; (2) direct coronary thromboembolism from left atrial appendage; and (3) tachycardia episodes resulting in a supply–demand mismatch13. However, while AHRE, viewing as subclinical AF, is also recognized as an important clinical entity, therefore it may not always be considered in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack. As such, AHRE duration remains an important target of research. Future larger prospective studies are needed to explore which duration of AHRE may be the standard cutoff for further evaluation of MACE in patients with AHREs.

Most previous AHRE studies excluded patients with AF history4,10,14. We tried evaluating patients with and without AF history in order to identify possible differences. The results showed that only AHRE ≥ 5 min was independently associated with development of MACE, suggesting that in patients with documented history of AF, AHRE may have no important role in the occurrence of MACE.

The other issue we noted was about using anticoagulants in patients with AHRE, even though such a large review of data is not warranted. When we come across a patient with AHRE ≥ 5-min and CHA2DS2-VASc scores > 2 in our daily practice, we follow the current recommendation of 2016 ESC guideline15. At the third Joint Consensus Conference of the German Atrial Fibrillation Network (AFNET) and the European Heart Rhythm Association on AF, an algorithm was proposed for management of patients with AHRE16. Current updated guidelines recommend that in patients with AHRE ≥ 24 h, clinicians should view them with regard to AF and initiate treatment with a DOAC based on CHA2DS2-VASc scores in order to prevent stroke16. Evidence of MACE prevention in AHRE patients is lacking. Results of one study showed that DOAC therapy reduced MI compared with VKA therapy in AF patients17. However, other study data showed that the presence of AF was independently associated with a heightened risk of MI despite a lower baseline burden and progression rate of coronary atheroma18. Also, aspirin was suggested to have benefit for primary prevention of MACE in specific groups, including among subgroups defined by age, statin use, diabetes and smoking19. One study showed that statin use tended to be associated with lower risk of new-onset AF after AMI20, but no evidence was found supporting an association between risk and new onset AHRE. Two large ongoing trials (NOAH-AFNET 6 and ARTESiA)21,22 will address unmet needs regarding the effectiveness of edoxaban and apixaban for stroke and systemic embolism in patients with AHRE. Further studies are needed to focus on this issue and determine definitively whether patients with new-onset AHRE are at greater risk of MACE, including AF.

Previous studies23,24 have shown that AHREs were associated with thromboembolic events in Asian patients. Moreover, two proposed models postulated that atrial cardiomyopathy might play a key role between AHRE and the risk of future ischemic stroke25,26. Systemic vascular risk factors accompanied aging can lead to abnormal atrial substrates subsequently resulting in atrial cardiomyopathy, which interacts with hypercoagulability and may be related to atrial dilatation, atrial inflammation/fibrosis, endothelial dysfunction, and/or mechanical dysfunction.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, this is a single-center, retrospective, and observational study in a hospital-based setting with a relatively small number of included patients, and all patients were Taiwanese. As a result, causality cannot be inferred between AHRE and MACE and results may have been affected by confounding factors. Also, results cannot likely be generalized to other populations. Second, AHRE may have been underestimated due to different default settings for AHRE in devices designed by different companies. The device was viewed as a confounder in the multivariable analysis and was not an independent factor for MACE. Prospective multicenter studies with larger samples are required to confirm results of the present study.

Conclusion

Patients with dual chamber pacemakers who develop AHRE have significantly increased risk of MACE, particularly those with history of AF or history of MI. However, although this patient population is at increased risk of MACE, the impact on MACE by different cutoff points for AHRE duration in different subpopulations such as those with history of AF or MI must be considered when evaluating risk. Patients with or without history of AF history may have the same cutoff for predicting MACE, but those with MI history may have a lower cutoff point than those without MI.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Convergence CT for assistance with English editing of the manuscript.

Author contributions

W.D.L. and J.Y.C. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared Figs. 1 and 2. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of China, Taiwan, for financially supporting this research under contract MOST 108-2218-E-006-019 and MOST 109-2218-E-006-024.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

These authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kirchhof P, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2016;50:e1–e88. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezw313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Healey JS, et al. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:120–129. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soliman EZ, et al. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174:107–114. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pastori D, et al. Atrial high-rate episodes and risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2020;109:96–102. doi: 10.1007/s00392-019-01493-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Diabetes Association Summary of Revisions: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42:S4–S6. doi: 10.2337/dc19-Srev01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams B, et al. 2018 Practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. Blood Press. 2018;27:314–340. doi: 10.1080/08037051.2018.1527177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Authors/Task Force Members, ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) & ESC National Cardiac Societies 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis. 2019;290:140–205. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eknoyan G, et al. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;3:5–14. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thygesen K, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018;72:2231–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishinarita R, et al. Burden of implanted-device-detected atrial high-rate episode is associated with future heart failure events-clinical significance of asymptomatic atrial fibrillation in patients with implantable cardiac electronic devices. Circ. J. 2019;83:736–742. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-18-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez M, et al. Newly detected atrial high rate episodes predict long-term mortality outcomes in patients with permanent pacemakers. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:2214–2221. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Witt CT, et al. Early detection of atrial high rate episodes predicts atrial fibrillation and thromboembolic events in patients with cardiac resynchronization therapy. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:2368–2275. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Violi F, Soliman EZ, Pignatelli P, Pastori D. Atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction: A systematic review and appraisal of pathophysiologic mechanisms. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003347. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camm AJ, et al. Atrial high-rate episodes and stroke prevention. Europace. 2017;19:169–179. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirchhof P, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur. Heart J. 2016;37:2893–2962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirchhof P, et al. Comprehensive risk reduction in patients with atrial fibrillation: Emerging diagnostic and therapeutic options—A report from the 3rd Atrial Fibrillation Competence NETwork/European Heart Rhythm Association consensus conference. Europace. 2012;14:8–27. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee CJ, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018;72:17–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bayturan O, et al. Atrial fibrillation, progression of coronary atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Prevent. Cardiol. 2017;24:373–381. doi: 10.1177/2047487316679265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelbenegger G, et al. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis with a particular focus on subgroups. BMC Med. 2019;17:198. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1428-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tseng CH, et al. Statins reduce new-onset atrial fibrillation after acute myocardial infarction: A nationwide study. Medicine. 2020;99:e18517. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirchhof P, et al. Probing oral anticoagulation in patients with atrial high rate episodes: Rationale and design of the Non-vitamin K antagonist Oral anticoagulants in patients with Atrial High rate episodes (NOAH-AFNET 6) trial. Am. Heart J. 2017;190:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopes RD, et al. Rationale and design of the Apixaban for the Reduction of Thrombo-Embolism in Patients With Device-Detected Sub-Clinical Atrial Fibrillation (ARTESiA) trial. Am. Heart J. 2017;189:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawakami H, et al. Clinical significance of atrial high-rate episodes for thromboembolic events in Japanese population. Heart Asia. 2017;9:e010954. doi: 10.1136/heartasia-2017-010954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li YG, et al. Atrial high-rate episodes and thromboembolism in patients without atrial fibrillation: The West Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Project. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019;292:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakano M, Kondo Y, Nakano M, Kajiyama T, Kobayashi Y. Atrial high rate episodes and atrial cardiomyopathy on the future stroke. J. Cardiol. 2019;74:394–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2019.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamel H, Okin PM, Elkind MS, Iadecola C. Atrial fibrillation and mechanisms of stroke: time for a new model. Stroke. 2016;47:895–900. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.