Abstract

Liver rupture in pregnancy is an acute condition with significant risk to the mother and fetus. It is known to occur with tumors such as hepatic adenoma, infective causes such as abscess, granulomatous diseases, and parasitic infections, and rarely spontaneously. Most of these conditions have overlapping clinicoradiological findings, almost always requiring histopathological confirmation. We report a case of a ruptured hepatic lesion, with an unusual diagnosis of Bartonella henselae infection causing cat-scratch disease, in a 24-year-old pregnant lady.

Keywords: cat-scratch disease, hemorrhagic liver lesion, liver rupture in pregnancy

Abbreviations: ALFP, Acute liver failure in pregnancy; CSD, Cat-scratch disease; CT, Computed tomography; FNH, Focal nodular hyperplasia; HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma; HELLP, Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet; IFA, Immunofluorescent assay; Ig-G, Immunoglobulin-G; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; PCR, Polymerase chain reaction; USG, Ultrasonography

Liver masses in pregnancy are rare. They can be classified as neoplastic and non-neoplastic. Among the neoplastic causes hepatic hemangioma, adenomas, focal nodular hyperplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are common.1 Non-neoplastic masses include simple cysts, infectious causes such as amoebic abscess, parasitic infections, and granulomatous diseases.2 Most of the liver lesions are asymptomatic, and the symptomatic ones present with vomiting, nausea, and right upper quadrant pain. Infectious causes may present with fever, malaise, anorexia in addition to the afore mentioned symptoms.2 These symptoms usually overlap with discomforts associated with the general course of pregnancy and thus may lead to a delay in the diagnosis.

Rupture of the liver in pregnancy is an acute condition, the causes being liver tumors such as adenoma, HCC, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet) syndrome, and rarely acute liver failure in pregnancy (ALFP) or spontaneous rupture in an uncomplicated pregnancy.3 Liver rupture has also been reported secondary to echinococcal infection, amoebic abscess, malaria, and syphilis.3 We report a case of a 24-year-old pregnant woman presenting because of liver rupture secondary to an unusual infectious etiology.

Case report

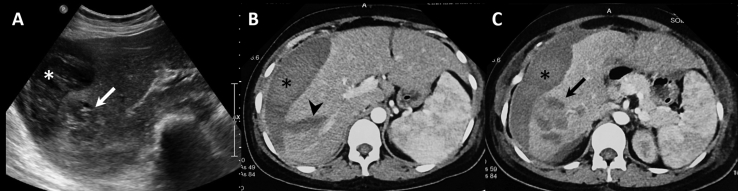

A 24-year-old primigravida, at 31 weeks of gestation, presented to a local hospital with sudden onset pain in the right hypochondrium, associated with on and off low-grade fever and malaise for the past one month. She was otherwise well with no comorbidities and an uneventful antenatal period. There was no history of hypertension or trauma. Clinical examination revealed low blood pressure (90/60 mm of Hg), tachycardia (pulse rate: 142/min), temperature of 100 °F, and pallor with no evidence of lymphadenopathy. Abdominal examination revealed mild tenderness in the right hypochondrium with abdominal distension and uterus corresponding to the period of gestation. Ultrasonography of the abdomen showed a heteroechoic lesion in segment VI and VII of the liver, predominantly hypoechoic with hyperechoic areas, subcapsular hematoma, and hemoperitoneum (Figure 1A). The lesion showed no significant vascularity within. There was intrauterine fetal demise. The subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan showed a heterogeneous predominantly hypodense lobulated lesion in segment VI and VII of the liver with few enhancing areas within. There was adjacent liver laceration, associated subcapsular hematoma, and hemoperitoneum (Figure 1B, C). A provisional diagnosis of a ruptured hepatic adenoma was made. Assisted breech delivery was done to deliver the dead fetus. Following initial stabilization, the patient was referred to our center for further management.

Figure 1.

A – Ultrasonography image shows a heteroechoic lesion in segment VI of the liver (arrow) with perihepatic collection (asterisk). B, C – Axial contrast-enhanced CT images show perihepatic hematoma (asterisk) with linear laceration (arrow head) and a heterogeneous lesion in segment VI (arrow). CT, computed tomography.

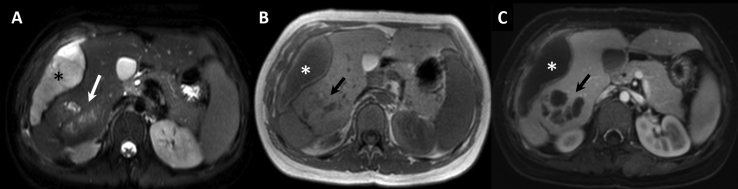

Laboratory investigations revealed a hemoglobin of 10 g/dL and a total leukocyte count of 8900/μL with a raised differential eosinophil count of 9.7%. The serum alkaline phosphatase was elevated (575 IU/L; normal: 80–240 IU/L). Other liver function tests were unremarkable. Contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed subsequently for better characterization of the liver lesion, showed a conglomerate lobulated lesion in segment VI of the liver, appearing heterogeneously hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Figure 2). On T1-weighted images, the lesion was hypointense with hyperintense areas which were suggestive of hemorrhage. A linear tract was noted in segments VI and VII extending from the posterior aspect of the lesion and communicating with the subcapsular collection suggesting liver laceration with contained rupture. The lesion showed mild peripheral contrast enhancement with nonenhancing cystic areas. Multiple lymph nodes were noted at the porta hepatis. Due to the presence of blood products within the lesion, a provisional diagnosis of hepatic adenoma was made. However, possibility of a parasitic infection was also considered in view of the elevated eosinophil count, conglomerated cystic areas within the lesion, and lymph nodes at the porta hepatis.

Figure 2.

A – Axial T2-weighted MRI shows a heterogeneous lesion (arrow) in segment VI of the liver with subcapsular hematoma (asterisk). B – Axial T1-weighted MRI shows the lesion appearing iso to hyperintense (arrow) with hematoma (asterisk). C – Contrast enhanced T1-weighted MRI shows nonenhancing cystic areas (arrow) within the lesion, with subcapsular hematoma (asterisk). MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

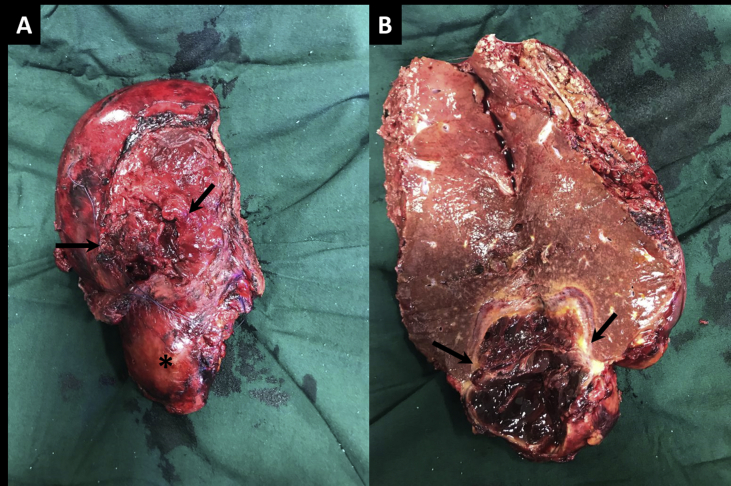

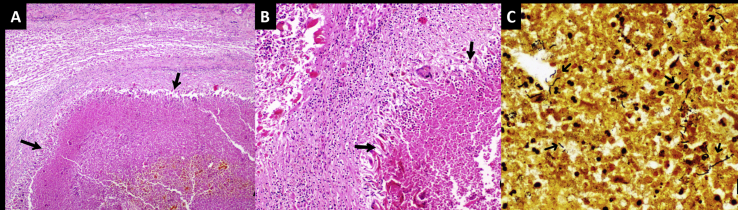

With the provisional diagnosis of a ruptured hepatic adenoma the patient underwent right hepatectomy. Intraoperatively, an exophytic solid-cystic mass was noted in segment VI and VII of the liver with ruptured liver capsule and intralesional hematoma (Figure 3). Histopathology of the specimen showed geographical abscess cavities lined by palisaded histiocytes, few multinucleated giant cells, numerous Charcot–Leyden crystals and eosinophil-rich mixed inflammatory cells (Figure 4). Warthin–Starry stain revealed occasional spiral bacilli within the abscess cavity. Serology performed was positive for Bartonella henselae immunoglobulin-G (Ig-G) on immunofluorescence assay (IFA) with the Ig-G titer of 1:256. Polymerase chain reaction(PCR)on tissue and blood samples showed a faint positive band. The patient had no pet cats, but there was history of exposure to cats in the neighborhood. In view of this history, positive serology, and suggestive histopathology, a diagnosis of cat scratch disease (CSD) was made. At six months follow-up, the patient is doing well.

Figure 3.

A – Right hepatectomy specimen shows capsular breach (arrows) with exophytic lesion in segment VI (asterisk). B – Cut-section through the lesion shows internal haemorrhage (arrows).

Figure 4.

A, B - Histology (H and E stain) of liver lesion shows a geographical abscess (arrows in A; H and E stain, x40) surrounded by palisaded histiocytes (arrows in B; x100). C - Warthin–Starry stain shows a few curved stain-positive bacilli within the abscess cavities suggestive of Bartonella henselae (x 400).

Discussion

Cat-scratch disease is caused by B. henselae, a gram-negative bacillus. It is inoculated with the bite, lick, or scratch of a cat. The most common presentation is regional lymphadenitis at the site of scratch, although it may present as disseminated infection.4 Hepatosplenic involvement occurs in 0.3–0.7% of the cases.5 Hepatosplenic CSD has been reviewed in children and commonly presents with fever and abdominal pain. Lymphadenopathy may be absent.6 CSD is classified as a vascular proliferative disease (in immunocompromised patients) or a necrotizing granulomatous disease (most often in immunocompetent hosts). Hepatosplenic CSD on imaging presents with multiple abscesses in the liver or spleen.6 On ultrasonography, the liver lesions in CSD are generally hypoechoic, ranging from well-defined homogenous to indistinct and heterogeneous lesions.7 Our case showed a predominantly hypoechoic lesion with few hyperechoic areas, secondary to hemorrhage. On CT scan, the lesions may show any of the three different patterns which include: persistent hypoattenuation relative to the liver (index case), isoattenuation relative to the surrounding tissues, and rim enhancement.7 On MRI, the lesions show low signal intensity on T1-weighted and high signal on T2-weighted images and may show peripheral contrast enhancement.7

Eosinophilia with cystic lesions in the liver has also been noted with echinococcus, hepatic fascioliasis, and visceral larva migrans.8 In cases where regional lymphadenitis is absent, the diagnosis may be delayed. Serologic investigations for CSD include enzyme immunoassay, indirect IFA, and western blot techniques. IFA has high sensitivity and specificity for Bartonella species. Infection with B. henselae is probable when the Ig-G titer is ≥ 1:256, possible with titers between 1:64 and 1:256 and less likely with titer ≤1:64.9 PCR for B. henselae can be performed on both blood and tissue samples. Although it has variable sensitivity (76%), the specificity is high (100%).10 The Warthin–Starry stain aids tissue diagnosis by allowing visualization of B. henselae as brown black bacilli against a yellow amber background. As preoperative serology or histopathology aids in making this diagnosis, particularly in clinically suspected cases, we stress the importance of preoperative sampling of the lesion to avoid an unnecessary major surgery.

Spontaneous rupture with hemorrhage is known to occur with solid liver lesions such as hemangioma, adenoma, or hepatocellular carcinoma. Other causes include patients with HELLP syndrome, hyper eosinophilic syndrome, ALFP, and also spontaneous rupture.11 Rupture of parasitic cysts is also a known entity with echinococcus species being a common cause.2 Rupture of eosinophilic liver abscesses has been reported previously.12 B. henselae has been reported to cause spontaneous splenic rupture13; but liver rupture has not been reported. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in which CSD is the etiology.

Pregnancy causes a state of altered cell immunity which increases the risk of infection.14 These infections usually cause mild fever or mild abdominal pain which may be masked by the general symptoms of pregnancy. CSD in pregnancy can cause a febrile state and bacteremia in the mother and also poses a risk to the fetus because of risk of perinatal transmission.15 However, pregnancy is not known to increase the risk of rupture of liver lesions in CSD.

There is lack of clear guidelines on the antibiotic regimen for the management of CSD. Currently, azithromycin is recommended as the therapy of choice. A few studies have shown the benefit of oral azithromycin 500 mg per day for 5 days in the treatment of hepatosplenic CSD.16 A few case studies have also suggested corticosteroids for the treatment of prolonged fever in hepatosplenic CSD.17 However, a systematic review evaluating the treatment guidelines for CSD concluded that the available data do not support the use of antibiotics for the management of CSD as no particular antibiotic regimen has shown to be beneficial in improving the cure rate or time to achieve cure.18

In conclusion, this is the first case of hepatic CSD presenting with spontaneous rupture during pregnancy. This case report highlights the importance of making a preoperative diagnosis. Exposure to cats, history of fever, peripheral eosinophilia, and radiologic features suggesting inflammatory lesions were all present but ascertained in retrospect. Appropriate workup for the causative organism in the form of serology, culture, or PCR, and preoperative histopathology should be carried out; this may allow a more conservative approach in the management of these cases.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ayushi Agarwal: Writing - original draft. Danny Joy: Involved in patient care and surgery. Prasenjit Das: Histopathology review. Nihar R. Dash: Involved in patient care and liver surgery. Deep N. Srivastava: Writing - review & editing. Kumble S. Madhusudhan: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Srinivasa S., Lee W.G., Aldameh A., Koea J.B. Spontaneous hepatic haemorrhage: a review of pathogenesis, aetiology and treatment. HPB. 2015 Oct;17:872–880. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Athanassiou A.M., Craigo S.D. Liver masses in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 1998 Apr 1;22:166–177. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(98)80049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou X., Zhang M., Liu Z. A rare case of spontaneous hepatic rupture in a pregnant woman. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18 doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1713-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Margileth A.M. Cat scratch disease. Adv Pediatr Infect Dis. 1993;8:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atıcı S., Kadayıfcı E.K., Karaaslan A. Atypical presentation of cat-scratch disease in an immunocompetent child with serological and pathological evidence. Case Rep Pediatr. 2014;2014:397437. doi: 10.1155/2014/397437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arisoy E.S., Correa A.G., Wagner M.L., Kaplan S.L. Hepatosplenic cat-scratch disease in children: selected clinical features and treatment. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 1999 Apr;28:778–784. doi: 10.1086/515197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mortelé K.J., Segatto E., Ros P.R. The infected liver: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2004 Jul;24:937–955. doi: 10.1148/rg.244035719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laroia S.T., Rastogi A., Bihari C., Bhadoria A.S., Sarin S.K. Hepatic visceral larva migrans, a resilient entity on imaging: experience from a tertiary liver center. Tropenmed Parasitol. 2016 Jan 1;6:56. doi: 10.4103/2229-5070.175100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uluğ M. Evaluation of cat scratch disease cases reported from Turkey between 1996 and 2013 and review of the literature. Cent Eur J Publ Health. 2015;23:170–175. doi: 10.21101/cejph.a4040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hansmann Y., DeMartino S., Piémont Y. Diagnosis of cat scratch disease with detection of Bartonella henselae by PCR: a study of patients with lymph node enlargement. J Clin Microbiol. 2005 Aug;43:3800–3806. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.3800-3806.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frise C.J., Davis P., Barker G., Wilkinson D., Mackillop L. Hepatic capsular rupture in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016 Dec;9:185–188. doi: 10.1177/1753495X16670480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang S.Y., Tak W.Y., Kweon Y.O. Spontaneous rupture of eosinophilic liver abscess. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Dec;26:1440–1443. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daybell D., Paddock C.D., Zaki S.R. Disseminated infection with Bartonella henselae as a cause of spontaneous splenic rupture. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Aug 1;39:e21–e24. doi: 10.1086/422001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yip L., McCluskey J., Sinclair R. Immunological aspects of pregnancy. Clin Dermatol. 2006 Apr;24:84–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilavsky E., Amit S., Avidor B., Ephros M., Giladi M. Cat scratch disease during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Mar;119:640–644. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182479387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García J.C., Núñez M.J., Castro B. Hepatosplenic cat scratch disease in immunocompetent adults: report of 3 cases and review of the literature [published correction appears in Medicine (Baltimore) Medicine (Baltim) 2014;93:267–279. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000089. 2014 Dec;93(28):1. López, Asunción [Added]] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phan A., Castagnini L.A. Corticosteroid treatment for prolonged fever in hepatosplenic cat-scratch disease: a case study. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2017 Dec;56:1291–1292. doi: 10.1177/0009922816684606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prutsky G., Domecq J.P., Mori L. Treatment outcomes of human bartonellosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2013 Oct 1;17:e811–e819. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]