Abstract

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) are attractive options for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D) because they effectively lower A1C and weight while having a low risk of hypoglycemia. Some also have documented cardiovascular benefit. The GLP-1 RA class has grown in the last decade, with several agents available for use in the United States and Europe. Since the efficacy and tolerability, dosing frequency, administration requirements, and cost may vary between agents within the class, each agent may offer unique advantages and disadvantages. Through a review of phase III clinical trials studying dulaglutide, exenatide twice daily, exenatide once weekly, liraglutide, lixisenatide, semaglutide, and oral semaglutide, 14 head-to-head trials were identified that evaluated the safety and efficacy of GLP-1 RA active comparators. The purpose of this review is to provide an analysis of these trials. The GLP-1 RA head-to-head clinical studies have demonstrated that all GLP-1 RA agents are effective therapeutic options at reducing A1C. However, differences exist in terms of magnitude of effect on A1C and weight as well as frequency of adverse effects.

Keywords: GLP-1 receptor agonist, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes is rising worldwide. Globally, it is estimated that 463 million people have diabetes, correlating with a prevalence of 9.3%.1 Type 2 diabetes (T2D), which accounts for roughly 95% of all cases, remains challenging to manage despite the plethora of treatment options. Beta-cell function declines progressively, often necessitating treatment intensification over time to achieve or maintain glycemic control. Current diabetes treatment guidelines recommend a patient-specific approach to treatment. When selecting drug therapy, the clinician should consider cardiovascular comorbidities, hypoglycemia risk, impact on weight, cost, risk of adverse effects, and patient preferences.2,3 The glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) are attractive options for the treatment of T2D because they effectively lower A1C and weight while having a low risk of hypoglycemia. Some GLP-1 RAs also have documented cardiovascular benefits. The GLP-1 RA class has grown in the last decade with several agents available for use in the United States (US) and Europe. To explore differences in efficacy and tolerability within the class, we published a review of head-to-head clinical studies of GLP-1 RAs in 2015.4 Since that time, several additional studies with newer agents have been published. Thus, the purpose of this review is to provide an updated analysis of current head-to-head comparative data of GLP-1 RAs. Of note, there are no head-to-head trials comparing cardiovascular or renal outcomes, thus this review is limited to outcomes related to glycosylated hemoglobin (A1C), weight, adverse effects, and patient satisfaction.

GLP-1 RAs: general effects and comparisons

GLP-1 RAs increase glucose-dependent insulin secretion and decrease inappropriate glucagon secretion, delay gastric emptying and increase satiety. There are currently seven approved GLP-1 receptor agonists (Table 1); exenatide twice daily, lixisenatide once daily, liraglutide once daily, exenatide once weekly, dulaglutide once weekly, semaglutide once weekly, and oral semaglutide once daily. Of note, due to steady decline in sales, albiglutide (a once weekly GLP-1 RA) was discontinued in 2017. For this reason, albiglutide was not included in this review. All of the GLP-1 RA agents are administered via subcutaneous (SC) injection, except for oral semaglutide. Although rates of adverse effects differ between specific agents, the most common adverse effects with the GLP-1 RA class are gastrointestinal (GI) related (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) and injection site reactions. Several key differences exist between the products in terms of molecular structure, pharmacokinetics, dosing frequency, and administration (Table 1) that may lead to important differences in efficacy, tolerability, and patient satisfaction.5–12 With the considerable heterogeneity and complexity across the class of GLP-1 RAs, each agent should be evaluated independently, as opposed to assuming a class effect, and head-to-head clinical trials can lend important information regarding differences within the GLP-1 RA class.

Table 1.

Currently available GLP-1 RAs.

| Drug | Approval date (US, EMA) | Phase III clinical trial program | Base | Homology to native GLP-1 (%) | Dose and frequency | Route | Tmax | Half-life | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-acting | Exenatide (Byetta®) | 28 April 2005, 20 November 2006 | AMIGO | Exendin-4 | 53 | 5–10 mcg twice daily | SC | 2.1 h | 2.4 h |

| Lixisenatide (Adlyxin®, Lyxumia®) | 28 July 2016, 1 February 2013 | GetGoal | Exendin-4 | 50 | 10–20 mcg once daily | SC | 1–3.5 h | 3 h | |

| Long-acting | Liraglutide (Victoza®) | 25 January 2010, 30 June 2009 | LEAD | Human GLP-1 | 97 | 0.6–1.8 mg once daily | SC | 8–12 h | 13 h |

| Exenatide (Bydureon®) | 26 January 2012, 17 June 2011 | DURATION | Exendin-4 | 53 | 2 mg once weekly | SC | 2.1–5.1 h | NR | |

| Dulaglutide (Trulicity®) | 18 September 2014, 21 November 2014 | AWARD | Human GLP-1 | 90 | 0.75–1.5 mg once weekly | SC | 24–72 h | 5 days | |

| Semaglutide (Ozempic®) | 5 December 2017, 8 February 2018 | SUSTAIN | Human GLP-1 | 94 | 0.25–1 mg once weekly | SC | 1–3 days | 1 week | |

| Oral Semaglutide (Rybelsus®) | 20 September 2019, 3 April 2020 | PIONEER | Human GLP-1 | 94 | 3–14 mg once daily | PO | 1 h | 1 week |

EMA, European Medicines Agency; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; NR, not reported; PO, by mouth; SC, subcutaneous; US, United States.

Head-to-head clinical studies

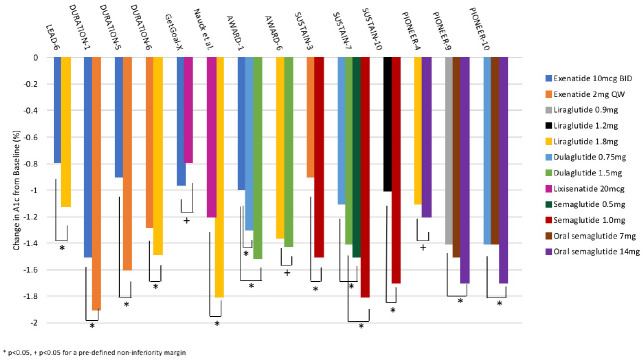

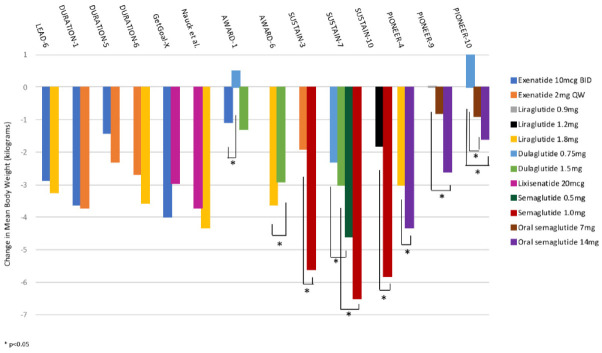

The GLP-1 RA agents have all been evaluated extensively in phase III clinical programs. Through a review of phase III clinical trials for exenatide twice daily, lixisenatide, liraglutide, exenatide once weekly, dulaglutide, semaglutide, and oral semaglutide, we identified 14 head-to-head trials that evaluated the safety and efficacy of GLP-1 RA active comparators.13–26 Of the 13 trials, 7 were included in our original publication; 1 trial (HARMONY-7)27 in our original publication that compared albiglutide with liraglutide was removed.4 A summary of the design and baseline characteristics of the head-to-head studies is provided in Table 2. Figures 1 and 2 display the differences in A1C and weight, respectively, observed within these studies.

Table 2.

GLP-1 RAs: summary of head-to-head clinical trials.

| Study | Study size and duration | Baseline characteristics |

Background therapy | Active comparators | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | A1C (%) | Weight (kg); BMI (kg/m2) | Duration of diabetes (years) | ||||

| LEAD-6 (Buse et al.)13 | N = 464, 26 weeks | 57 | 8.1 | 93; 32.9 | 8.2 | Metformin, SU, or both | Exenatide 10 mcg BID Liraglutide 1.8 mg QD |

| DURATION-1 (Drucker et al.)14 | N = 295, 30 weeks | 55 | 8.3 | 102; 35 | 6.7 | Drug naïve or metformin, SU, TZD or a combination of two of those agents | Exenatide 10 mcg BID Exenatide 2 mg QW |

| DURATION-5 (Blevins et al.)15 | N = 252, 24 weeks | 56 | 8.4 | 96; 33.3 | 7 | Drug naïve or metformin, SU, TZD or any combination | Exenatide 10 mcg BID Exenatide 2 mg QW |

| DURATION-6 (Buse et al.)16 | N = 911, 26 weeks | 57 | 8.5 | 91; 32.3 | 8.5 | Metformin, SU, both, or metformin + pioglitazone | Exenatide 2 mg QW Liraglutide 1.8 mg QD |

| GetGoal-X (Rosenstock et al.)17 | N = 634, 24 weeks | 57 | 8.0 | 95; 33.6 | 6.8 | Metformin | Lixisenatide 20 mcg QD Exenatide 10 mcg BID |

| Liraglutide versus Lixisenatide (Nauck et al.)18 | N = 404 26 weeks | 56 | 8.4 | 101.2; 34.7 | 6.4 | Metformin | Liraglutide 1.8 mg QD Lixisenatide 20 mcg QD |

| AWARD-1 (Wysham et al.)19 | N = 978, 52 weeks | 56 | 8.1 | 96; 33 | 9 | Metformin + pioglitazone | Dulaglutide 1.5 mg QW Dulaglutide 0.75 mg QW Exenatide 10 mcg BID Placebo |

| AWARD-6 (Dungan et al.)20 | N = 599, 26 weeks | 57 | 8.1 | 94; 33.5 | 7.2 | Metformin | Dulaglutide 1.5 mg QW Liraglutide 1.8 mg QD |

| SUSTAIN-3 (Ahmann et al.)21 | N = 813, 56 weeks | 57 | 8.3 | 96; 34 | 9.2 | Metformin, SU, TZD | Semaglutide 1.0 mg QW Exenatide 2 mg QW |

| SUSTAIN-7 (Pratley et al.)22 | N = 1201, 40 weeks | 56 | 8.2 | 95; 33.5 | 7.4 | Metformin | Semaglutide 0.5 mg QW Semaglutide 1.0 mg QW Dulaglutide 0.75 mg QW Dulaglutide 1.0 mg QW |

| SUSTAIN-10 (Capehorn et al.)23 | N = 577, 30 weeks | 59.5 | 8.2 | 97; 33.7 | 9.3 | Metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitor, SU, DPP-4 inhibitor, AG | Semaglutide 1 mg QW Liraglutide 1.2 mg QD |

| PIONEER-4 (Pratley et al.)24 | N = 711, 52 weeks | 56 | 8.0 | 94; 33 | 7.6 | Metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitor | Oral semaglutide 14 mg QD Liraglutide 1.8 mg QD Placebo |

| PIONEER-9 (Yamada et al.)25 | N = 243, 52 weeks | 59 | 8.2 | 71; 25.9 | 7.6 | Metformin, DPP-4 inhibitor, SGLT-2 inhibitor, AG, SU | Oral semaglutide 3 mg QD Oral semaglutide 7 mg QD Oral semaglutide 14 mg QD Liraglutide 0.9 mg QD Placebo |

| PIONEER-10 (Yabe et al.)26 | N = 458, 57 weeks | 59 | 8.3 | 72; 26.2 | 9.4 | DPP-4 inhibitor, TZD, AG, SU | Oral semaglutide 3 mg QD Oral semaglutide 7 mg QD Oral semaglutide 14 mg QD Dulaglutide 0.75 mg QW |

A1C, hemoglobin A1C; AG, α-glucosidase inhibitor; BID, twice daily; BMI, body mass index; kg, kilogram; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; QD, once daily; QW, once weekly; SU, sulfonylurea; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Figure 1.

Changes in A1C values with GLP-1 RAs in head-to-head clinical studies.

*p < 0.05. +p < 0.05 for a pre-defined non-inferiority margin.

A1C, hemoglobin A1C; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists.

Figure 2.

Changes in weight with GLP-1 RAs in head-to-head clinical studies.

*p < 0.05

GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists.

Efficacy

The LEAD-6 trial compared liraglutide with exenatide twice daily in patients with uncontrolled T2D being treated with maximally tolerated doses of metformin, sulfonylurea (SU), or both.13 Liraglutide reduced A1C significantly more than exenatide twice daily (−1.12% versus −0.79%, p < 0.0001, Figure 1), while improving the proportion of patients achieving an A1C of <7% (54% versus 43%, respectively, p = 0.0015). Additionally, liraglutide resulted in a larger reduction in mean fasting plasma glucose (FPG) compared with exenatide twice daily (−1.61 mmol/l versus −0.60 mmol/l, p < 0.0001). The percentage of subjects achieving weight loss (liraglutide 78% versus exenatide 76%) and overall weight loss (liraglutide −3.24 kg versus exenatide 2.87 kg, p = 0.22) was similar between groups (Figure 2).

The DURATION-1 study compared exenatide once weekly with exenatide twice daily in patients with uncontrolled T2D being treated with either diet, one or two oral therapies.14 After 30 weeks, exenatide once weekly reduced A1C significantly more compared with the twice daily formulation (−1.9% versus −1.5%, p = 0.0023). The percentage of patients achieving a goal A1C of ⩽7% was also greater with exenatide once weekly compared with exenatide twice daily (77% versus 61%, p = 0.0039). Body weight decreased similarly between the two groups throughout the 30 week study with a −3.7 kg and −3.6 kg reduction from baseline in the exenatide weekly and twice daily groups, respectively (p = 0.89). An extension study of DURATION-1 to 52 weeks was conducted by Buse et al.28 The extension study converted the exenatide twice daily patients to the weekly formulation while those originally randomized to exenatide once weekly continued this therapy. After 52 weeks patients continued on the once weekly exenatide maintained an A1C improvement (−2.0%), while those switching from twice daily to once weekly further reduced A1C to achieve a similar reduction in A1C as those originally on exenatide once weekly.

The DURATION-5 study also compared exenatide once weekly with exenatide twice daily.15 After 24 weeks, a significant reduction in A1C was observed with once weekly compared with twice daily exenatide (−1.6% versus −0.9%, p < 0.0001). As with the DURATION-1 trial, exenatide once weekly significantly lowered FPG when compared with the twice daily formulation (−1.9 versus −0.7 mmol/l, p = 0.0008). The proportion of patients achieving an A1C < 7% was 58% and 30% in the weekly and twice daily exenatide groups, respectively (p < 0.0001). A similar reduction in body weight was observed between groups.

Exenatide once weekly was compared with liraglutide in patients with T2D who were being treated with lifestyle modification and oral antihyperglycemic drugs in the DURATION-6 trial.16 Reductions in A1C from baseline were significantly greater in patients taking liraglutide compared with exenatide once weekly (−1.48% versus −1.28%, p = 0.02). However, the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval (CI) did not meet predefined non-inferiority criteria (95% CI 0.08–0.33). The proportion of patients achieving an A1C < 7% was 60% and 53% in the liraglutide and exenatide once weekly groups, respectively (p = 0.0011). Patients in the liraglutide group demonstrated superior weight loss of 0.9 kg compared with exenatide once weekly (−3.57 versus −2.68, p = 0.0005). Both liraglutide and exenatide significantly reduced FPG from baseline (−2.12 versus −1.76 mmol/l, p = 0.02).

The GetGoal-X trial compared the efficacy and safety of lixisenatide with exenatide twice daily in patients with uncontrolled T2D on metformin.17 The mean change in A1C was −0.79% in the lixisenatide group compared with −0.96% in the exenatide twice daily group, which met predefined criteria for non-inferiority (95% CI 0.033–0.297). A similar proportion of patients in each group achieved a goal A1C of <7% (48.5% lixisenatide and 49.8% exenatide, p = NS). Body weight was reduced significantly in both groups, though a greater reduction was seen with exenatide (lixisenatide −2.96 kg versus exenatide −3.98 kg; 95% CI 0.45–1.58).

A 26-week randomized control trial conducted by Nauck et al. compared lixisenatide 20 mcg once daily with liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily as add on therapy to metformin.18 Treatment with liraglutide resulted in a significantly greater reduction in A1C compared with lixisenatide (−1.8% versus −1.2%, p < 0.0001). In addition, liraglutide also significantly reduced FPG from baseline more than lixisenatide (−2.9 mmol/l versus −1.7 mmol/l, p < 0.0001) and showed better reductions in mean 9-point self-measured plasma glucose compared with lixisenatide (p < 0.0001). Similarly, a significantly larger percentage of patients using liraglutide reached an A1C goal of less than 7% (liraglutide = 74.2%, lixisenatide = 45.5%). Both drugs had similar body weight reductions (−4.3 kg for liraglutide, −3.7 kg for lixisenatide, p = 0.23).

Two different doses of dulaglutide (1.5 mg and 0.75 mg) given weekly were compared with exenatide twice daily and placebo in the AWARD-1 study.19 Patients had uncontrolled T2D on either metformin or thiazolidinediones. Changes in A1C at 26 weeks were −1.51%, −1.30%, −0.99%, and −0.46% for the dulaglutide 1.5 mg, dulaglutide 0.75 mg, exenatide, and placebo groups, respectively. Both doses of dulaglutide were superior to exenatide (p < 0.001). A greater percentage of patients achieving an A1C of <7% was observed with dulaglutide 1.5 and 0.75 mg groups compared with exenatide (78% and 66% versus 52%, p < 0.001 for both comparisons). Similarly, dulaglutide was associated with a greater reduction in the mean of all pre-meal plasma glucose (p < 0.001) and post-prandial plasma glucose (p = 0.047) compared with exenatide. Change in weight over 26 weeks was −1.30 kg, +0.2 kg, −1.07 kg, and +1.24 kg for dulaglutide 1.5 mg, dulaglutide 0.75 mg, exenatide, and placebo, respectively. The difference in weight loss between exenatide twice daily and dulaglutide 1.5 mg was not significant (−0.24 kg, p = 0.474), although there was a statistical difference between exenatide twice daily and dulaglutide 0.75 mg (−1.27 kg, p < 0.001).

The AWARD-6 trial compared once weekly dulaglutide 1.5 mg versus daily liraglutide 1.8 mg in T2D patients on metformin.20 Mean change in A1C was −1.42 and −1.36 in the dulaglutide and liraglutide groups, respectively (95% CI −0.19 to 0.07, non-inferiority p value < 0.0001), thus meeting predefined non-inferiority criteria. Both groups resulted in 68% of patients achieving an A1C of <7%. Weight reduction was significantly greater in the liraglutide groups compared with dulaglutide [−3.61 kg versus −2.90 kg; (95% CI 0.17–1.26), p = 0.011].

The SUSTAIN-3 trial randomized patients on metformin, thiazolidinediones, and/or SUs to either SC semaglutide 1 mg or exenatide once weekly for 56 weeks.21 Semaglutide was superior to exenatide once weekly in regards to A1C reduction (−1.5% versus −0.9%; p < 0.0001). In addition, significantly more patients reached an A1C goal of less than 7% with semaglutide compared with exenatide once weekly (67% versus 40%, p < 0.0001). Semaglutide was also superior in reduction of the seven-point self-measured blood glucose profile (2.2 mmol/l versus 1.5 mmol/l, p < 0.0001) and mean FPG (2.8 mmol/l versus 2.0 mmol/l, p < 0.0001). There was also significantly more weight loss with semaglutide from baseline compared with exenatide once weekly (−5.6 kg versus −1.9 kg, p < 0.0001).

Patients on metformin were randomly assigned to either SC semaglutide 0.5 mg, SC semaglutide 1 mg, dulaglutide 0.75 mg, or dulaglutide 1.5 mg for 40 weeks in the SUSTAIN-7 trial.22 Semaglutide 0.5 mg improved A1C significantly more than dulaglutide 0.75 mg (−1.5% versus −1.1%, p < 0·0001). Additionally, semaglutide 1 mg also reduced A1C significantly more compared with dulaglutide 1.5 mg (−1.8% versus −1.4%, p < 0.0001). A larger proportion of patients significantly reached an A1C goal of less than 7% or less than 6.5% with semaglutide in the low-dose comparison arms (p < 0.0001) and the high-dose comparison arms (p = 0.0021). In addition, FPG values were significantly decreased with semaglutide 1 mg compared with dulaglutide 1.5 mg (−2.8 mmol/l versus −2.2 mmol/l, p = 0.005). Mean 7-point self-measured blood glucose values were decreased significantly with semaglutide in both the low-dose comparison arms (−2.4 mmol/l versus −2.0 mmol/l, p = 0.0014) and the high-dose comparison arms (−3 mmol/l versus −2.3 mmol/l, p < 0.0001). Patients achieved a greater reduction in body weight with semaglutide compared with dulaglutide for both low-dose comparison (−4.6 kg versus −2.3 kg, p < 0.0001) and high-dose comparison (−6.5 kg versus −3.0 kg, p < 0.0001).

The SUSTAIN-10 trial compared once-weekly semaglutide 1.0 mg with liraglutide 1.2 mg in patients on 1–3 oral antihyperglycemic agents in a 30 week randomized, controlled trial.23 Mean A1C decreased by 1.7% in the semaglutide group and 1.0% in the liraglutide group (p < 0.0001). Mean body weight decreased by 5.8 kg with semaglutide and 1.9 kg with liraglutide (p < 0.0001). The proportions of patients achieving an A1C < 7% or weight loss of ⩾5% were both significantly higher in the semaglutide group compared with the liraglutide group (p < 0.0001 for both).

The PIONEER-4 trial examined the first oral GLP-1 receptor agonist, semaglutide, in comparison with subcutaneous liraglutide and placebo in a 52-week randomized controlled trial. Patients were on either metformin or a SGLT-2 inhibitor at baseline.24 The primary endpoint was change in A1C from baseline to week 26 using the treatment policy estimand (which assessed treatment effect for all participants assigned to treatment regardless of study drug discontinuation or use of rescue medication). At 26 weeks, oral semaglutide was non-inferior (−1.2% versus −1.1%, 95% CI −0.3 to 0.00, p < 0.0001) to liraglutide in A1C reduction. There were no significant differences in percentage of patients achieving an A1C target of less than 7% between oral semaglutide and liraglutide (67.6% versus 61.8%, p = 0.1530). After 26 weeks, oral semaglutide resulted in significantly more weight loss than liraglutide (−4.4 kg versus −3.1 kg, p = 0.0003). After 52 weeks of treatment, oral semaglutide reduced A1C significantly more than liraglutide (−1.3% versus −1.1%, p < 0.0001).

The PIONEER-9 trial compared oral semaglutide monotherapy to liraglutide in a 52-week randomized controlled trial.25 Patients were assigned randomly to one of three doses of oral semaglutide (3 mg, 7 mg, and 14 mg), liraglutide 0.9 mg, or placebo for 52 weeks. This study was conducted in Japanese patients on oral antihyperglycemic therapy. Researchers used a dose of 0.9 mg of liraglutide as the comparator based on the approved maximum dose in Japan. The primary endpoint was change in A1C from baseline to week 26 using the trial product estimand (which assumes all patients remained on trial product without rescue medication use). Oral semaglutide had a dose-dependent effect on A1C reduction. Semaglutide 14 mg had a significant A1C reduction compared with liraglutide (−1.7% versus −1.4%, p = 0.0272) at 26 weeks. A significantly larger percentage of patients taking semaglutide 14 mg reached a goal A1C of less than 7% compared with liraglutide (81% versus 53%, p = 0.0152) at 26 weeks. However, after 52 weeks, the difference in A1C reduction between oral semaglutide 14 mg and liraglutide were no longer significantly different (−1.5% versus 1.1%, p = 0.0632). Oral semaglutide 14 mg showed a more significant body weight reduction from baseline compared with liraglutide at week 26 (−2.4 kg versus 0 kg, p < 0.0001) and at week 52 (−2.6 kg versus 0 kg, p < 0.0001) in the treatment estimand arm. Similarly in the trial estimand arm, oral semaglutide 14 mg showed a more significant body weight reduction from baseline compared with liraglutide at week 26 (−2.4 kg versus 0 kg, p < 0.0001) and at week 52 (−2.8 kg versus 0 kg, p < 0.0001).

The PIONEER-10 trial randomized Japanese patients with T2D on oral antihyperglycemic therapy to receive either oral semaglutide 3 mg, 7 mg, 14 mg, or SC dulaglutide 0.75 mg for 57 weeks.26 A dose of 0.75 mg of dulaglutide was selected based on the maximum dose approved for use in Japan. The primary endpoint was the number of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) over 57 weeks. Secondary endpoints included change in A1C and weight from baseline at 52 weeks. After 52 weeks, oral semaglutide 14 mg had a more significant reduction in A1C compared with dulaglutide (−1.7% versus −1.4%, p = 0.0170). Dulaglutide had a greater A1C reduction than semaglutide 3 mg (−1.4% versus 0.9%, p = 0.0005) and similar A1C reduction compared with semaglutide 7 mg (−1.4% versus −1.4%). Significantly more patients on semaglutide 14 mg achieved an A1C goal compared with dulaglutide (71% versus 51%, p = 0.0016). Semaglutide 3 mg, 7 mg, and 14 mg all resulted in significant reduction in body weight compared with dulaglutide (0 versus 1 kg, p = 0.0476, −0.9 kg versus 1 kg, p < 0.0001, −1.6 kg versus 1 kg, p < 0.0001, respectively).

Safety/tolerability

The major AEs seen with the head-to-head GLP-1 RA trials are summarized in Table 3. Predictably, most of the AEs experienced were GI in nature. Across trials, however, there were some differences highlighted between comparators in regards to reported AEs.

Table 3.

GLP-1 RAs: a comparison of common adverse effects in head-to-head trials.

| Study | Active comparators | Nausea (%) | Vomiting (%) | Diarrhea (%) | Injection site reactions (%) | Withdrawal due to AEs (N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LEAD-6 (Buse et al.)13 | Exenatide 10 mcg BID | 65/232 (28.0) | 23/232 (9.9) | 28/232 (12.1) | 21/232 (9.1) | 31 |

| Liraglutide 1.8 mg QD | 60/235 (25.5) | 14/235 (6.0) | 29/235 (12.3) | 21/235 (8.9) | 23 | |

| DURATION-1 (Drucker et al.)14 | Exenatide 10 mcg BID | 50/145 (34.5) 39/148 | 27/145 (18.6) | 19/145 (13.1) | 17/145 (11.7) | 7 |

| Exenatide 2 mg QW | (26.4) | 16/148 (10.8) | 20/148 (13.5) | 33/148 (22.3) | 9 | |

| DURATION-5 (Blevins et al.)15 | Exenatide 10 mcg BID | 43/123 (35.0) | 11/123 (8.9) | 5/123 (4.1) | 16/123 (13) | 6 |

| Exenatide 2 mg QW | 18/129 (14.0) | 6/129 (4.7) | 12/129 (9.3) | 13/129 (10) | 6 | |

| DURATION-6 (Buse et al.)16 | Exenatide 2 mg QW | 43/461 (9.3) | 17/461 (3.7) | 28/461 (6.1) | 73/461 (15.8) | 12 |

| Liraglutide 1.8 mg QD | 93/450 (20.7) | 48/450 (10.7) | 59/450 (13.1) | 9/450 (2.0) | 25 | |

| GetGoal-X (Rosenstock et al.)17 | Lixisenatide 20 mcg QD | 78/318 (24.5) | 32/318 (10.1) | 33/318 (10.4) | 27/318 (8.5) | 33 |

| Exenatide 10 mcg BID | 111/316 (35.1) | 42/316 (13.3) | 42/316 (13.3) | 5/316 (1.6) | 41 | |

| Lixisenatide versus Liraglutide (Nauck et al.)18 | Liraglutide 1.8 mg QD | 44/202 (21.8) | 14/202 (6.9) | 25/202 (12.4) | Not Reported | 13 |

| Lixisenatide 20 mcg QD | 44/202 (21.8) | 18/202 (8.9) | 20/202 (9.9) | 15 | ||

| AWARD-1 (Wysham et al.)19 | Dulaglutide 1.5 mg QW | 78/279 (28.0) | 47/279 (16.8) | 31/279 (11.1) | 1/279 (0.4) | 8 |

| Dulaglutide 0.75 mg QW | 45/280 (16.1) | 17/280 (6.1) | 22/280 (7.9) | 0/280 (0) | 4 | |

| Exenatide 10 mcg BID | 71/276 (25.7) | 30/276 (10.9) | 16/276 (5.8) | 1/276 (0.4) | 9 | |

| Placebo | 8/141 (5.7) | 2/141 (1.4) | 8/141 (5.7) | 0/141 (0) | 3 | |

| AWARD-6 (Dungan et al.)20 | Dulaglutide 1.5 mg QW | 61/299 (20.4) | 21/299 (7.0) | 36/299 (12.0) | 1/299 (0.3) | 18 |

| Liraglutide 1.8 mg QD | 54/300 (18.0) | 25/300 (8.3) | 36/300 (12.0) | 2/300 (0.7) | 18 | |

| SUSTAIN-3 (Ahmann et al.)21 | Semaglutide 1.0 mg QW | 90/404 (22.3) | 29/404 (7.2) | 46/404 (11.4) | 0/404 (0) | 38 |

| Exenatide 2 mg QW | 48/405 (11.9) | 25/405 (6.2) | 34/405 (8.4) | 49/405 (12.1) | 29 | |

| SUSTAIN-7 (Pratley et al.)22 | Semaglutide 0.5 mg QW | 68/301 (23) | 31/301 (10) | 43/301 (14) | 4/301 (1) | 24 |

| Semaglutide 1.0 mg QW | 63/300 (21) | 31/300 (19) | 41/300 (14) | 6/300 (2) | 29 | |

| Dulaglutide 0.75 mg QW | 39/299 (13) | 12/299 (4) | 23/299 (8) | 4/299 (1) | 14 | |

| Dulaglutide 1.0 mg QW | 60/299 (20) | 29/299 (10) | 53/299 (18) | 8/299 (3) | 20 | |

| SUSTAIN-10 (Capehorn et al.)23 | Semaglutide 1 mg QW | 63/289 (21.8) | 30/289 (10.4) | 45/289 (15.6) | Not reported | 33 |

| Liraglutide 1.2 mg QD | 45/287 (15.7) | 23/287 (8) | 35/289 (12.2) | 19 | ||

| PIONEER-4 (Pratley et al.)24 | Oral semaglutide 14mg QD | 56/285 (20) | 25/285 (9) | 43/285 (15) | Not applicable | 31 |

| Liraglutide 1.8 mg QD | 51/284 (18) | 13/284 (5) | 31/284 (11) | 26 | ||

| Placebo | 5/142 (4) | 3/142 (2) | 11/142 (8) | 5 | ||

| PIONEER-9 (Yamada et al.) 25 | Oral semaglutide 3 mg QD | 2/49 (4) | Not reported | 2/49 (4) | Not applicable | 1 |

| Oral semaglutide 7 mg QD | 5/49 (10) | 5/49 (10) | 1 | |||

| Oral semaglutide 14 mg QD | 4/48 (8) | 4/48 (8) | 2 | |||

| Liraglutide 0.9 mg QD | 0/48 (0) | 0/48 (0) | 0 | |||

| Placebo | 1/49 (2) | 1/49 (2) | 0 | |||

| PIONEER-10 (Yabe et al.)26 | Oral semaglutide 3 mg QD | 7/131 (5) | 3/131 (2) | 2/131 (2) | Not applicable | 4 |

| Oral semaglutide 7 mg QD | 11/132 (8) | 1/132 (1) | 2/132 (2) | 8 | ||

| Oral semaglutide 14 mg QD | 12/130 (9) | 9/130 (7) | 10/130 (8) | 8 | ||

| Dulaglutide 0.75 mg QW | 6/65 (9) | 1/65 (2) | 4/65 (6) | 2 |

AE, adverse events; BID, twice daily; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; QD, once daily; QW, once weekly.

In the LEAD-6 trial, overall AEs were lower with the liraglutide group, compared with exenatide twice daily, (74.9% versus 78.9%, respectively) but the severity of these effects where higher with liraglutide (serious AEs 5.1%, severe AEs 7.2%) than exenatide twice daily (serious AEs 2.6%, severe AEs 4.7%).13 There was no clear trend in the type of serious or severe AE experienced in either group. In general, GI side effects were similar across both treatment groups. It was observed that while initial nausea rates were similar between groups, nausea was less persistent in liraglutide compared with exenatide twice daily (reported at week 26 in 3% of liraglutide patients versus 9% in the exenatide twice daily group).

In the DURATION-1 trial, exenatide twice daily showed a higher incidence of both nausea and vomiting compared with the exenatide once weekly formulation, with similar rates of diarrhea.14 Injection site reactions were more common with the once weekly formulation.

DURATION-5 highlighted higher rates of nausea (and subsequent vomiting) with use of exenatide twice daily compared with the once-weekly formulation, with two patients in the twice daily arm reporting severe nausea, compared with none in the once weekly arm.15 Injection site reactions were again higher with the exenatide once weekly group, although the differences were smaller (13% versus 10%).

DURATION-6 showed higher rates of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea with the liraglutide-treated group, compared with exenatide once weekly.16 Both group noted an attenuation of these symptoms over time. Exenatide once weekly had higher reporting of injection site reactions, including nodule formation after injection.

Lixisenatide demonstrated slightly lower rates of reported GI side effects compared with exenatide twice daily in the GetGoal-X trial, with statistically lower rates of nausea (24.5% versus 35.1%, p < 0.05).17 These symptoms appeared to improve over time in both groups, although the exenatide twice daily group had a slightly longer attenuation time (5 weeks) compared with lixisenatide (3 weeks). Interestingly, this was one trial where there was an observed difference in the incidence of hypoglycemia; lixisenatide had statistically fewer episodes of symptomatic hypoglycemia compared with exenatide twice daily (2.5% versus 7.9%, p < 0.05). Neither group included patients taking concomitant SU therapy.

The Nauck trial comparing liraglutide with lixisenatide showed a slightly higher proportion of patients in the liraglutide group reporting total AEs (71.8% versus 63.9% with lixisenatide) and slightly higher serious AEs reported as well (5.9% versus 3.5%).18 That said, discontinuation rates due to AEs were similar and slightly higher in the lixisenatide group: 13 patients versus 15, respectively. GI symptoms once again were most prominent and similar across the two groups, although the liraglutide group reported loss of appetite at a higher rate (6.4% versus 2.5%) and showed higher increases in lipase (8.4% versus 2.5%).

For the AWARD-1 trial, GI AEs were similar between the 1.5 mg dulaglutide and exenatide groups, with nausea and vomiting being statistically higher than placebo at 26 weeks (p < 0.05).19 Slightly lower rates were seen with the lower dose 0.75 mg dulaglutide arm. All groups reported the highest incidence of GI events early (within the first 2 weeks) in treatment.

The AWARD-6 showed no difference in reported GI AEs between dulaglutide and liraglutide.20 The frequency of nausea in both groups peaked at week one and gradually declined thereafter.

The SUSTAIN-3 trial showed comparable overall AE rates between the semaglutide (75.0%) and the exenatide ER (76.3%) groups.21 Serious AEs were reported more frequently with semaglutide (9.4%) than exenatide ER (5.9%), as were discontinuation rates due to AEs (9.4% with semaglutide versus 7.2% exenatide ER). GI side effects were the most commonly reported in both groups, and higher with semaglutide (41.8% with semaglutide and 33.3% with exenatide ER), with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea reported as the most prevalent. These AEs did appear to diminish over time in most subjects on both study medications. Of note, there were two fatalities reported in the semaglutide group during the study period, one due to hepatocellular carcinoma and the other due to invasive breast carcinoma; in both cases the investigator determined they were unrelated to treatment with the study medication. Injection site reactions were notably higher in the exenatide ER group, occurring in 22.0% of subjects compared with 1.2% of semaglutide-treated subjects; 9 subjects discontinued treatment in the exenatide group due to injection site nodules, mass, or reactions.

Examining AEs in the SUSTAIN-7 trial, reported AEs occurred in 207 (69%) patients using semaglutide 1 mg, 204 (68%) patients using semaglutide 0.5 mg, 221 (74%) patients using dulaglutide 1.5 mg and 186 (62%) patients using dulaglutide 0.75 mg.22 Six patients died, one in each semaglutide group and two in each dulaglutide group. Serious AEs were reported in 23 (8%) and 17 (6%) patients using semaglutide 1 mg and 0.5 mg, respectively. For dulaglutide, serious AE rates were 22 (7%) and 24 (8%) for the 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg groups. GI side effects were again common across all four groups, with reported occurrence rates of 44% (semaglutide 1.0 mg), 43% (semaglutide 0.5 mg), 48% (dulaglutide 1.5 mg), and 33% (dulaglutide 0.75 mg). These events appeared to be dose-related for dulaglutide but not for semaglutide, where rates were similar across both dosage groups. AEs leading to discontinuation of therapy occurred in 10% and 8% for the semaglutide 1 mg and 0.5 mg groups and 7% and 5% for the dulaglutide 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg groups. An adjudication committee reviewed and confirmed a total of two patients and three patients having a cardiovascular (CV) event during the trial on semaglutide 1 mg and 0.5 mg, respectively, and six patients and five patients having a CV event in the 1.5 mg and 0.75 mg dulaglutide groups.

In the SUSTAIN-10 trial, safety profiles were generally similar between semaglutide 1 mg and liraglutide 1.2 mg, except GI AEs were higher in the semaglutide group (43.9% versus 38.3%).23 In addition, there was a higher proportion of AEs leading to treatment discontinuation with semaglutide compared with liraglutide (11.4% versus 6.6%).

For the PIONEER-4 trial, numbers of patients reporting AEs were 229 (80%) for oral semaglutide, 211 (74%) for liraglutide and 95 (67%) for the placebo group.24 Proportions of participants reporting serious AEs were higher for the semaglutide [31 (11%)] and placebo [15 (11%)] than with liraglutide [22 (8%)]. A total of eight deaths occurred during the trial, with three in the semaglutide group, four in the liraglutide group, and one in the placebo group. The investigator judged all deaths as being non-treatment related. Study treatment was discontinued in 31 (11%) patients using oral semaglutide, 26 (9%) using liraglutide and 5 (4%) using placebo medication. GI AEs were again the most prevalent, with oral semaglutide showing the highest rates of nausea (20%), vomiting (15%), and diarrhea (9%), followed by liraglutide (18%, 11%, and 5% respectively), and lowest rates (4%, 8% and 2%) in placebo. Of note, the patients in the liraglutide group had a peak occurrence of nausea earlier than with oral semaglutide, peaking at week 2 compared with week 8 with oral semaglutide, with rates decreasing after those times.

During the treatment phase of PIONEER-9, the liraglutide group reported the lowest rates of AEs (67%), followed by the oral semaglutide treatments, (71–76%) with the placebo group reporting the highest rates (80%).25 AEs were mild to moderate in nature, with only three patients reporting a severe AE (1 in the 3 mg semaglutide group and 2 in the 7 mg semaglutide group). Gastrointestinal symptoms were again prevalent across all groups, although in this trial nasopharyngitis was the most commonly occurring AE.

PIONEER-10 reported similar high rates of AEs, starting with 77% of patients in the 3 mg semaglutide group, increasing to 80% in the 7 mg group, and 85% in the 14 mg group; this was compared with 82% of patients using dulaglutide.26 Serious AEs were less linear, reported in nine patients (7%), four patients (3%), seven patients (5%) and one patient (2%), respectively. Infections (mainly nasopharyngitis and influenza) were the most prevalent AE reported, followed by GI symptoms.

Interestingly, both upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) and nasopharyngitis continue to be reported as AEs in patients receiving GLP-1 RA therapy. URIs were reported in the LEAD-6 (6.4% with liraglutide versus 6.0% with exenatide twice daily), DURATION-1 (8.1% of the exenatide twice daily group, 17.2% of the exenatide once weekly group), DURATION-5 (4.1% with exenatide twice daily, 7.0% with exenatide once weekly), DURATION-6 (3% in each group), and SUSTAIN-7 (5% and 3% in the two semaglutide groups and 7% and 5% for the two dulaglutide groups). It was also reported in the AWARD-1 trial, where rates were consistent across groups, including placebo (4% dulaglutide 1.5 mg, 5% dulaglutide 0.75 mg, 4% exenatide and 4% placebo). Nasopharyngitis was reported in LEAD-6 (11.5% liraglutide versus 13.4% exenatide), DURATION-6 (7% in each treatment group), Nauck study (6.4% liraglutide versus 9.9% lixisenatide), AWARD-1 (8% and 7% for dulaglutide 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg, 4% exenatide and 4% placebo), AWARD-6 (8% dulaglutide versus 7% liraglutide), SUSTAIN-3 (9.7% with semaglutide compared with 9.4% with exenatide ER), and SUSTAIN -7 (5% in both semaglutide groups, 6% 0.75 mg dulaglutide, 7% 1.5 mg dulaglutide). It was the most prevalent AE reported in both the PIONEER-9 (16–20% in semaglutide groups, 29% for liraglutide and placebo) and PIONEER-10 (26–30% with semaglutide groups, 29% dulaglutide). The mechanism for the GLP-1 RAs increasing URIs and nasopharyngitis cases has not been elucidated, but the consistency across trials suggests that these are still important considerations with this class.

Hypoglycemia

The rates of hypoglycemia were generally similar across GLP-1 RA treatment groups and were seen primarily in patients treated with concomitant SU therapy. Severe hypoglycemic episodes were rare across the trials, being reported in only six trials, (LEAD-6, AWARD-1, PIONEER-4, SUSTAIN-3, SUSTAIN-7, and SUSTAIN-10), all with rates of only 1–2%. Minor hypoglycemic rates across all trials ranged from 0% to 15.9% in patients without SU use, with most trials showing rates below 10%, as would be expected. These rates increased with SU therapy, demonstrating rates between 11% and 20%, with the exception of the LEAD-6 trial, where rates were 32.7% with patients using SUs and liraglutide, and 42% with the SU/exenatide combination. Overall, hypoglycemic concerns were of minor impact in these trials.

Patient satisfaction and adherence

When considering potential GLP-1 RA options for therapy, evaluating patient satisfaction and adherence with treatment becomes important. In the LEAD-6 trial, patient-reported outcomes, using the Diabetes Treatment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ), were significantly higher with liraglutide compared with exenatide twice daily.29 Specific items from the DTSQ scale that showed significant differences between the two groups included convenience, flexibility, recommend the therapy, and continue therapy. The DURATION-1 trial comparing exenatide twice daily with exenatide once weekly demonstrated significant DTSQ treatment satisfaction changes at 30 weeks with willingness to continue current treatment and perceived hypoglycemia frequency, both favoring the once weekly formulation.30 Patients using exenatide once weekly reported a significant increase in treatment satisfaction from baseline compared with exenatide twice daily, despite similar adherence rates (98%) between the two groups.30 The authors theorized this may be due to reduced frequency of injections. The AWARD-6 utilized a European quality-of-life five dimensions visual analog scale, which did not demonstrate any statistical differences between the dulaglutide and liraglutide groups.20

The SUSTAIN-3, 7, and 10 trials examined patient satisfaction through the DTSQ.21–23 In the SUSTAIN-3 trial, treatment satisfaction was higher with semaglutide than exenatide ER (p < 0.05). In addition, patients found semaglutide more convenient [estimated treatment difference (ETD) 0.25, 95% CI 0.07–0.44, p < 0.05]. Patients being treated with semaglutide were more satisfied with their treatment (ETD 0.20, 95% CI 0.04–0.36, p < 0.05) and were more likely to recommend it to someone else with T2D (ETD 0.20, 95% CI 0.04–0.36, p < 0.05). In the SUSTAIN-7 trial, patients felt that they had less unacceptable hyperglycemia with low dose semaglutide [ETD −0.32, 95% (CI −0.60 to −0.04, p < 0.0254] and high dose semaglutide [ETD −0.40, 95% CI −0.68 to −0.12, p < 0.0049] compared with dulaglutide. In the SUSTAIN-10 trial, patients showed treatment satisfaction favoring semaglutide over liraglutide in “feeling of unacceptably high blood sugars” but no other aspects of the STSQ scale showed significant differences between groups.

In the PIONEER-4 trial, at 52 weeks, there was no difference in treatment satisfaction between liraglutide and oral semaglutide in regards to their DTSQ scores.24 The PIONEER-9 trial utilized the Diabetes Therapy-Related QOL (DTR-QOL) questionnaire to assess patient satisfaction. Similar to the PIONEER-4 trial, the PIONEER-9 trial determined that there was no difference in treatment satisfaction, anxiety/dissatisfaction, and burden on daily and social activities between oral semaglutide and liraglutide at 52 weeks.25 The PIONEER-10 trial examined patient satisfaction using the DTR-QoL as well. Within the outcomes reported through the DTR-QoL survey, patients had significantly less anxiety and dissatisfaction with 7 mg [ETD 6.03, 95% CI 0.76–11.30] and 14 mg [ETD 7.21, 95% CI 1.91–12.51] oral semaglutide compared with dulaglutide.26

A 12-month retrospective observational study examined adherence and persistence in relation to dulaglutide, liraglutide, and exenatide once weekly.31 The group of patients taking dulaglutide were significantly more adherent compared with the group of patients taking liraglutide (51.2% versus 38.2%; p < 0.001) and exenatide once weekly (50.7% versus 31.9%; p < 0.001). In regards to persistence, the patients taking dulaglutide were more persistent than the group of patients taking liraglutide (55% versus 48.8%, p < 0.001) and exenatide ER (54.9% versus 34.4%, p < 0.001).

Another retrospective real-world observational study evaluated adherence by comparing dulaglutide to semaglutide and exenatide once weekly.32 At 6 months, patients on dulaglutide appeared to be more adherent compared with semaglutide patients (proportion of days covered: 75% versus 67%, p < 0.001) and exenatide ER patients (proportion of days covered: 75% versus 63%, p < 0.001). In addition, allowing for a 45-day gap, patients taking dulaglutide resulted in more persistent days than semaglutide (143.6 days versus 129.9 days, p < 0.001) and exenatide ER (142 days versus 121.4 days, p < 0.001).

A crossover study between the dulaglutide pen and semaglutide pen in 310 participants showed that more participants preferred the dulaglutide pen than the semaglutide pen (84.2% versus 12.3%, p < 0.0001) and more perceived the dulaglutide pen to have greater ease of use (86.8% versus 6.8%, p < 0.0001).33

Taken as a whole, it appears that changes in overall patient satisfaction may be related to transitioning away from twice daily GLP-1 RA treatment to a longer dosing-interval GLP-1 RA therapy. Within the once-weekly agents, dulaglutide, which offers less steps and no reconstitution or needle attachments requirements, may be favored by patients.

Discussion

The GLP-1 RA class offers important advantages in the treatment of T2D. All agents within the class have demonstrated significant reductions in A1C and the class generally has a favorable effect on weight with minimal risk of hypoglycemia. In addition, three of the GLP-1 RAs also have evidence at reducing major adverse cardiovascular events; dulaglutide, liraglutide, and injectable semaglutide. The use of GLP-1 RAs may be limited by the adverse effects (mostly GI and injection-site related), need for subcutaneous administration (except with the new oral semaglutide formulation), and cost. For those patients that would benefit from therapy with GLP-1 RAs, clinicians should consider the available literature regarding comparative effects on A1C and weight, rates of adverse effects, as well as administration requirements and cost when selecting a specific agent within the class.

To date, 14 direct head-to-head studies between GLP-1 RAs have been published. These studies confirm that differences exist regarding the magnitude of effect of different agents within the class on A1C, weight, and GI adverse effects. Evaluating the head-to-head studies in total, we offer a summary of the within-class comparability (Table 4). In general terms, it appears that the long-acting agents result in greater A1C lowering than the short-acting agents, with semaglutide leading to the greatest A1C reduction. Out of the long-acting agents, exenatide XR appears to have the least impact on A1C, although it still produces more A1C lowering compared with the short-acting agents. In terms of A1C lowering, the agents could be ranked (from highest to lowest) in the following order: subcutaneous semaglutide > oral semaglutide > dulaglutide = liraglutide > exenatide XR > exenatide (twice daily) = lixisenatide.

Table 4.

Summary of head-to-head trial data for GLP-1 receptor agonists.

| Drug | Within class comparability of A1C lowering efficacy | Within class comparability of effect on weight | Within class comparability of GI adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exenatide (twice daily) | Low | Low | Highest |

| Lixisenatide | Low | Low | Intermediate |

| Liraglutide | High | High | Intermediate |

| Exenatide XR | Intermediate | Low | Low |

| Dulaglutide | High | Intermediate | Intermediate/high |

| Semaglutide | Highest | Highest | High |

| Semaglutide (oral) | High/highest | Highest | Intermediate/high |

A1C, hemoglobin A1C; GI, gastrointestinal; GLP-1 RA, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists.

In regards to weight, there is more ambiguity with the differentiation between agents. The long-acting agents tend to produce more significant weight loss compared with the short-acting agents, with semaglutide once again taking the lead on the greatest weight reduction. In terms of weight loss, the agents could be ranked (from most to least) in the following order: semaglutide > liraglutide > dulaglutide > exenatide XR = exenatide (twice daily) = lixisenatide.

GI adverse effects appear to be highest with the short-acting agents as well as subcutaneous semaglutide and appear to be lowest with exenatide XR. Injection site reactions may be more common with the longer acting agents, particularly exenatide once-weekly, which can cause transient small nodules at the injection site. However, patient satisfaction data indicate that once weekly injections result in higher patient satisfaction compared with twice daily injections. Comparing just the once weekly agents, patient satisfaction appears highest for dulaglutide, which is a single-use, disposable pen device that requires few steps. Discontinuation rates due to adverse events vary between agents and studies, but are low overall with less than 10% of patients in the studies discontinuing GLP-1 RA therapy due to adverse events. In clinical practice, discontinuation rates are likely to be higher, possibly due to less time and resources dedicated to patient education, support, and follow up. The risk of hypoglycemia is low with GLP-1 RAs and rates were similar across all GLP-1 RA treatment groups in the head-to-head clinical studies; although the risk was increased with concomitant SU therapy.

The purpose of this review was to provide an analysis of current head-to-head comparative data of GLP-1 RAs. The impact of different agents on A1C, weight, and GI adverse effects should play an integral role in the selection of an agent within the class. However, there are several other important factors that may influence the choice of GLP-1 RA. Clinicians should use a patient-centered approach when selecting a specific GLP-1 RA agent, incorporating evidence on A1C and weight efficacy as well as evidence regarding the reduction of major cardiovascular events. Importantly, current guidelines prioritize the use of GLP-1 RAs with demonstrated CV benefit (dulaglutide, liraglutide, and injectable semaglutide) in patients with atherosclerotic CV disease (ASCVD) and ASCVD risk, independent of baseline A1C. This recommendation should be prioritized over considerations of within class differences in effects on A1C, weight, or GI AEs.2 In addition, other practical considerations such as self-administration requirements, patient preference, and cost cannot be ignored, especially considering the high rates of non-adherence and non-persistence with GLP-1 RAs.34,35 Most importantly, given these important medication and patient-specific factors, the selection of a specific agent within the GLP-1 RA class should be based on more than just which agent is available based on formulary and insurance restrictions.

Conclusion

The phase III studies that have compared GLP-1 RA agents head-to-head have demonstrated that all GLP-1 RA agents are effective therapeutic options at reducing A1C. However, differences clearly exist in terms of magnitude of effect on A1C and weight as well as frequency and severity of adverse effects. A comprehensive review of all head-to-head data indicates that subcutaneous semaglutide appears to offer the best A1C and weight reduction but also has higher rates of GI AEs. The other once weekly agents have good A1C and weight effects and may cause less GI AEs compared with the once daily or twice daily options. The short-acting agents have less impact on A1C and weight and high rates of GI AEs, and thus should not routinely be considered first-line agents. The magnitude of effect on A1C, weight, and GI AEs should be considered when selecting a specific agent within the GLP-1 RA class.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Jennifer Trujillo: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Data analysis, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing, Final approval

Wes Nuffer: Methodology, Data analysis, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing, Final approval

Brooke Smith: Data analysis, Writing-original draft, Writing-review and editing, Final approval

Conflict of interest statement: JT (Sanofi, advisory board member)

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Jennifer M. Trujillo  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7898-8029

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7898-8029

Wesley Nuffer  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3355-4582

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3355-4582

Contributor Information

Jennifer M. Trujillo, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Mail Stop C238, 12850 E. Montview Blvd., V20-1222, Aurora, CO 80045, USA.

Wesley Nuffer, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Aurora, CO, USA.

Brooke A. Smith, University of Colorado Skaggs School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Aurora, CO, USA

References

- 1. International Diabetes Federation. IDF diabetes atlas. 9th ed. Brussels, Belgium: IDF, 2019. https://www.diabetesatlas.org (accessed 1 July 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Diabetes Association. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2021. Diabetes Care 2021; 44(Suppl. 1): S111–S124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus statement by the American Association of clinical endocrinologists and American College of endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm – 2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract 2020; 26: 107–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Ellis SL. GLP-1 receptor agonists: a review of head-to-head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2015; 6: 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trujillo JM. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists. In: White JR. (ed.) Guide to medications for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Arlington County, VA: American Diabetes Association, 2020, pp.190–210. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Byetta (exenatide) injection [product information]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adlyxin (lixisenatide) injection [product information]. Bridgewater, NJ: Sanofi-aventis, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Victoza (liraglutide) injection [product information]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk Inc, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bydureon BCise (exenatide extended release) injectable suspension [product information]. Wilmington, DE: AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Trulicity (dulaglutide) injection [product information]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ozempic (semaglutide) injection [product information]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk Inc, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rybelsus (semaglutide) tablets [product information]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk Inc, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomised, parallel-group, multinational, open-label trial (LEAD-6). Lancet 2009; 374: 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drucker DJ, Buse JB, Taylor K, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus twice daily for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority study. Lancet 2008; 372: 1240–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Blevins T, Pullman J, Malloy J, et al. DURATION-5: exenatide once weekly resulted in greater improvements in glycemic control compared with exenatide twice daily in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 1301–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buse JB, Nauck M, Forst T, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION-6): a randomised, open-label study. Lancet 2013; 381: 117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosenstock J, Raccah D, Koranyi L, et al. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once daily versus exenatide twice daily in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin: a 24-week, randomized, open-label, active-controlled study (GetGoal-X). Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 2945–2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nauck M, Rizzo M, Johnson A, et al. Once-daily liraglutide versus lixisenatide as add-on to metformin in type 2 diabetes: a 26-week randomized controlled clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: 1501–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wysham C, Blevins T, Arakaki R, et al. Efficacy and safety of dulaglutide added onto pioglitazone and metformin versus exenatide in type 2 diabetes in a randomized controlled trial (AWARD-1). Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 2159–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dungan KM, Povedano ST, Forst T, et al. Once-weekly dulaglutide versus once-daily liraglutide in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD-6): a randomised, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2014; 384: 1349–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ahmann AJ, Capehorn M, Charpentier G, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide versus exenatide ER in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 3): a 56-week, open-label, randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care 2018; 41: 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pratley RE, Aroda VR, Lingvay I, et al. Semaglutide versus dulaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 7): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018; 6: 275–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Capehorn MS, Catarig AM, Furberg JK, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly semaglutide 1.0mg vs once-daily liraglutide 1.2mg as add-on to 1-3 oral antidiabetic drugs in subjects with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 10). Diabetes Metab 2020; 46: 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pratley R, Amod A, Hoff ST, et al. Oral semaglutide versus subcutaneous liraglutide and placebo in type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 4): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3a trial. Lancet 2019; 394: 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yamada Y, Katagiri H, Hamamoto Y, et al. Dose-response, efficacy, and safety of oral semaglutide monotherapy in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 9): a 52-week, phase 2/3a, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020; 8: 377–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yabe D, Nakamura J, Kaneto H, et al. Safety and efficacy of oral semaglutide versus dulaglutide in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 10): an open-label, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020; 8: 392–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pratley RE, Nauck MA, Barnett AH, et al. Once-weekly albiglutide versus once-daily liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on oral drugs (HARMONY 7): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority phase 3 study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2: 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Buse JB, Drucker DJ, Taylor KL, et al. DURATION-1: exenatide once weekly produces sustained glycemic control and weight loss over 52 weeks. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 1255–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schmidt WE, Christiansen JS, Hammer M, et al. Patient-reported outcomes are superior in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with liraglutide as compared with exenatide, when added to metformin, sulphonylurea or both: results from a randomized, open-label study. Diabet Med 2011; 28: 715–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Best JH, Boye KS, Rubin RR, et al. Improved treatment satisfaction and weight-related quality of life with exenatide once weekly or twice daily. Diabet Med 2009; 26: 722–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mody R, Huang Q, Yu M, et al. Adherence, persistence, glycaemic control and costs among patients with type 2 diabetes initiating dulaglutide compared with liraglutide or exenatide once weekly at 12real-world setting in the United States. Diabetes Obes Metab 2019; 21: 920–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mody R, Yu M, Nepal BK, et al. Dulaglutide has higher adherence and persistence than semaglutide and exenatide QW: 6-month follow-up from US Real-World Data. Paper presented virtually at the 80th American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions, 12–16 June 2020. Abstract 928-P. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Matza LS, Boye KS, Sterward DK, et al. Crossover clinical trial assessing patient preference between the dulaglutide pen and the semaglutide pen (PREFER). Diabetes Met Obes 2020; 22: 355–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Flory J, Gerhard T, Stempniewicz N, et al. Comparative adherence to diabetes drugs: an analysis of electronic health records and claims data. Diabetes Obes Metab 2017; 19: 1184–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wilke T, Mueller S, Groth A, et al. Non-persistence and non-adherence of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in therapy with GLP-1 receptor agonists: a retrospective analysis. Diabetes Ther 2016; 7: 105–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]