Abstract

Background

Vancomycin variable enterococci (VVE) are van-positive isolates with a susceptible phenotype that can convert to a resistant phenotype during vancomycin selection.

Objectives

To describe a vancomycin-susceptible vanA-PCR positive ST203 VVE Enterococcus faecium isolate (VVESwe-S) from a liver transplantation patient in Sweden which reverted to resistant (VVESwe-R) during in vitro vancomycin exposure.

Methods

WGS analysis revealed the genetic differences between the isolates. Expression of the van-operon was investigated by qPCR. Fitness and stability of the revertant were investigated by growth measurements, competition and serial transfer.

Results

The VVESwe-R isolate gained high-level vancomycin (MIC >256 mg/L) and teicoplanin resistance (MIC = 8 mg/L). VVESwe-S has a 5′-truncated vanR activator sequence and the VVESwe-R has in addition acquired a 44 bp deletion upstream of vanHAX in a region containing alternative putative constitutive promoters. In VVESwe-R the vanHAX-operon is constitutively expressed at a level comparable to the non-induced prototype E. faecium BM4147 strain. The vanHAX operon of VVESwe is located on an Inc18-like plasmid, which has a 3–4-fold higher copy number in VVESwe-R compared with VVESwe-S. Resistance has a low fitness cost and the vancomycin MIC of VVESwe-R decreased during in vitro serial culture without selection. The reduction in MIC was associated with a decreased vanA-plasmid copy number.

Conclusions

Our data support a mechanism by which vancomycin-susceptible VVE strains may revert to a resistant phenotype through the use of an alternative, constitutive, vanR-activator-independent promoter and a vanA-plasmid copy number increase.

Introduction

Enterococcus faecium is an important opportunistic pathogen causing severe MDR infections in hospitalized patients. The increase in VRE causes concerns due to severely limited treatment options. Vancomycin resistance occurs by the acquisition of one of several van-gene clusters—vanA, B, C, D, E, G, L, M, and N—of which vanA and vanB are the most significant clinically.1

Vancomycin-variable enterococci (VVE) is a term used for VRE where expression of the van genes is phenotypically silenced by genetic rearrangements, which may be reversed under vancomycin selection.2,3 A complex of seven genes (vanRSHAXYZ) support the expression of the prototype VanA-type high-level vancomycin and teicoplanin resistance. Upon exposure to glycopeptides the two-component regulators, sensor VanS and activator VanR, up-regulate the expression of the enzymes (VanHAXY) involved in changing the peptidoglycan sidechain terminus from d-Ala-d-Ala to d-Ala-d-Lac. However, only expression of vanHAX is essential in gaining resistance in strains with a functional host d-alanine:d-alanine ligase (Ddl).4 In 2009, a Canadian ST18 VVE. faecium was able to convert to a resistant phenotype by the introduction of IS elements providing novel promoters for constitutive expression of vanHAX and deletions in the promoter region.5,6 By 2015–16, a regional spread of VVE in the Ontario region had occurred and 47% of the vanA-positive isolates were VVE.7 In 2016, a Danish ST1421 VVE. faecium strain with a 252 bp vanX-truncation was described. The resistant phenotype was associated with an increased vanA-plasmid copy number or by disruption of the host ddl ligase gene.8 By 2019 this clone had spread from the capital region to all five Danish regions, and the Faroe Islands.9 Early identification of VVEs and their reversion mechanism is important for therapeutic and infection control measures.

We have previously described a VVE. faecium ST203 outbreak strain in Norway, where excision of a vanA-operon-inserted ISL3 restored the resistant phenotype.3 The occurrence of VVE will likely increase corresponding to the increase in VanA-type VRE as the vanA-gene cluster will be affected by random genetic alterations.

In this study, we show yet another different variant of variable resistance in a Swedish VVE strain.

Materials and methods

Isolation of VVE

The susceptible parental faecal VVE strain (VVESwe-S) was isolated from a liver-transplanted patient at Halmstad Hospital, Sweden after faecal VRE-screening, but the patient never had an E. faecium infection. The VRE-screening was performed by enrichment in Bile aesculin azide (BEA) broth supplemented with aztreonam (60 mg/L) and vancomycin (4 mg/L) at 36°C for 20–24 h and subsequent vanA/B PCR using Rotor-Gene and TaqMan probes.10

Vancomycin resistance phenotype reversion and frequency

Conversion to vancomycin resistance was initiated as described previously3 by incubating a single susceptible VVE colony in 5 mL of Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth (Oxoid) overnight, followed by a 1:100 dilution into 5 mL of BHI broth containing 2 or 8 mg/L vancomycin.

Resistance reversion frequency determination was based on Sivertsen et al.3 Ten-fold serial dilution samples of an overnight VVESwe-S strain BHI-broth culture in biological triplicates and technical triplicates were plated on BHI agar with and without 6 mg/L vancomycin. The plates were incubated at 35°C and cfu counted after 24 h for plates without vancomycin and after 48 h and 72 h for plates with vancomycin. Vancomycin-resistant revertant (VVESwe-R) colonies from vancomycin-containing plates were verified by MALDI-TOF (Bruker), antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST), and Sanger sequencing of the vanSH PCR product using primers as described before11 and BigDye 3.1 technology (Applied Biosystems). AST was performed with vancomycin MIC test strips (Liofilchem) and/or Sensititre EUENCF plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturers’ instructions with ATCC 29212 as control. JumpStart REDTaq ReadyMix (Merck KGaA) was used for PCRs. DNA extractions for PCRs were performed using the NucliSens EasyMAG instrument and reagents (BioMeriéux) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

WGS and bioinformatics

Bacterial genomic DNA was isolated with the Qiagen MagAttract HMW DNA isolation kit (Qiagen) and sequenced by MiSeq using Nextera library construction on 250 bp paired-end runs or by NextSeq500 using the Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit and the Mid Output 300 cycles cell according to standard protocols (Illumina). Sequence reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic v.0.36,12 assembled with Spades v.3.9.0,13 and annotated with Prokka v.1.11.14 MLST profiles were determined using MLST software15 and core genome (cg)MLST cluster types (CTs) were determined using SeqSphere+.16

In order to confirm the location of the vanA-gene cluster, the genomes were closed by nanopore sequencing technology. Nanopore reads were error-corrected and assembled along with Illumina reads by the hybrid assembler Unicycler v0.4.7.17 Resistance genes and the replicon type of van-operon-containing plasmid sequences were identified by scanning the genomes in Abricate v.8.5 using the NCBI resistance database and PlasmidFinder database, respectively. Illumina reads were mapped on the nanopore assemblies using bwa-mem.18 Genome coverage was calculated by bedtools genomcov option,19 which permitted quantifiable coverage ratios between the chromosome and the vanA-containing plasmid. VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R sequences were compared with MUMmer v3.2320 and the SNPs were called using GATK. Genome syntenies of the VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R genomes and between the VVESwe-S/-R vanA gene cluster and prototypic Tn1546 (GenBank Acc. No. M97297) were visualized with ACT,21 and alignment figures were produced with EasyFig v.2.2.2.22 Sanger sequencing of the vanSH region was performed on the prototypic Tn1546 as described above to confirm that the sequence has not changed in reference strain BM4147.

Promoters were predicted in the intergenic region between vanS and vanH using Softberry.23

Accession numbers

The sequences have been posted to NCBI and can be found under the BioProject number PRJNA551094 (CP041261-8 and CP041270-8).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) on cDNA and qPCR on gDNA

Quantification of mRNA levels of vanRS and vanHAX was done as described previously. Primer sequences for qPCR were also described previously.3

For quantification of gDNA levels of vanRS and vanHAX, DNA was extracted from VVESwe-S, VVESwe-R and BM4147 grown to mid-log-phase in BHI broth without and with 8 mg/L vancomycin, using the GenElute Bacterial Genomic DNA Kit (Sigma Aldrich). qPCR was performed using probes with 5′FAM and a 3′BHQ-1 quencher (Eurogentec), qPCR Master Mix Plus Low ROX (Eurogentec) and run on a 7300 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Cycle threshold (Ct) values were normalized to the housekeeping gene gdh and ΔCt was calculated as ΔCtvanRS = CtvanRS−Ctgdh and ΔCtvanHAX = CtvanHAX−Ctgdh. The plasmid copy number was calculated as 2ΔCt(vanHAX) since only one copy of gdh is found in all strains, and vanHAX only localizes to the plasmid of interest (based on Lee et al.24).

Statistical data analysis of qPCR data was performed in GraphPad Prism 7 using an unpaired two-tailed t-test.

Fitness measurements

The relative fitness was assessed through growth rate measurements and head-to-head competition as described previously.25

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in BHI and growth was measured in an Epoch 2 Spectrophotometer with Gen5 Software (BioTek Instruments Inc.) at 37°C, shaking at 425 rpm, with OD600 measurement every tenth minute for 24 h. Growth rates were calculated in the logarithmic growth phase with the program GrowthRates.26 The relative fitness was calculated by comparing the growth rates of VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R using the equation w = GrowthRateVVESwe-R/GrowthRateVVESwe-S.

For pairwise competition, overnight cultures of VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R were OD-adjusted (OD600), mixed at a ratio of 1:1 and diluted 1:100 in 5 mL BHI and incubated for 24 h at 37°C with shaking. The initial and final cfu counts of the competitors were determined on BHI agar without and with 8 mg/L vancomycin. The relative fitness w of the revertant VVESwe-R was estimated as a ratio of ln(cfu t24/cfu t0) of the revertant to the susceptible VVESwe-S using the equation w = ln(cfuVVESwe-Rt24/cfuVVESwe-Rt0)/ln(cfuVVESwe-St24/cfuVVESwe-St0).27

Statistical data analysis for fitness cost experiments was performed in GraphPad Prism 7 using an unpaired two-tailed t-test to calculate whether the value significantly differs from 1.

Resistance stability in VVESwe-R

The revertant was cultured continuously in absence of antibiotic with serial transfer every 24 h in biological triplicates (30 μL inoculated into 3 mL BHI). Colonies were counted on BHI plates with and without 8 mg/L vancomycin and the ratio of total cfu to resistant cfu was determined. Colonies were counted after 24 h and re-checked after 48 h, since the colonies were growing slowly on the selective plates. One hundred colonies were exposed to differential plating on BHI plates without and with 8 mg/L vancomycin.

Ten colonies were selected for qPCR analysis to determine vanA-plasmid copy, subjected to Sanger sequencing of the vanSH PCR product as described above and vancomycin MIC test strip (MTS-Liofilchem) with E. faecalis ATCC 29212 and E. faecium BM4147 as control strains.

Results and discussion

VVESwe resistance phenotype reversion and frequency

The original VVE faecal sample gave a positive vanA-PCR result from the BEA broth culture which supported growth of single colonies of enterococci on chromogenic and blood agar. Disc diffusion showed an inhibition zone diameter of 15 mm with a sharp edge and Etest gradient strips a vancomycin MIC of 2 mg/L. The isolate was named VVESwe-S. In broth microdilution VVESwe-S expressed susceptibility to vancomycin (MIC 1 mg/L) and teicoplanin (MIC <0.5 mg/L) (Tables S1 and S2, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

The VVESwe-S strain reverted to a vancomycin-resistant phenotype (VVESwe-R) during exposure to vancomycin 6 mg/L or 8 mg/L for 48–72 h. VVESwe-R had gained high-level vancomycin resistance (MIC >256 mg/L) and teicoplanin resistance (MIC 8 mg/L) (Table S2). The frequency of vancomycin resistance reversion was 2 × 10−8 resistant colonies per parent cell in vitro after 48 h and 5 × 10−8 after 72 h. A similar reversion frequency (3 × 10−8 after 24 h, 7 × 10−8 after 48 h) was also detected for the previously described VVE. faecium ST203 outbreak strain from Norway, although the reversion mechanism was different.3 A bacterial load of above 108 could be reached in certain infection sites (e.g. infected peritoneal fluids) in a patient28 and thus reversion is clinically relevant and may occur during vancomycin treatment as previously observed for other VVE strains.2,3 The VVE isolates reverted at a frequency that is too low and over a time that is too long to be detected by standard antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods, which explains why VVE resistant revertants are difficult to detect by standard AST methods using a much lower inoculum (105 bacteria) and reading after 24 h.

Genetic differences between VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R

VVESwe belongs to ST203/CT20 and is unrelated to any global or local surveillance isolates or the Norwegian ST203/CT465 VVE.3 Early detection of the VVESwe by PCR may have hindered the spread of this clone before it became prevalent. However, vanA-positive ST203/CT20 strains were prevalent in Germany among VRE blood culture isolates (2015–18), but expressed a normal VanA phenotype (G. Werner, personal communication).

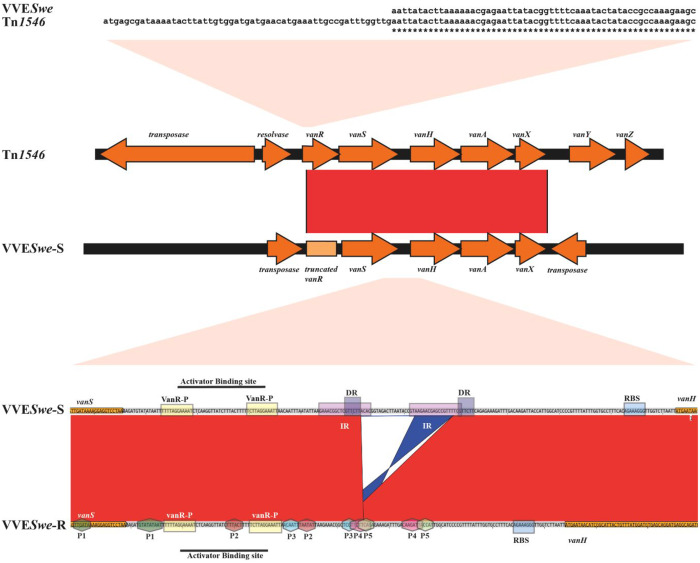

High-quality assemblies were achieved for VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R genomes with pertinent genome size, GC content, and coverage of 305× and 252×, respectively. The genomes of the parental VVESwe-S and the resistant revertant VVESwe-R were compared and aligned with the prototypical vanA cluster of BM4147. Both VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R have a 5′-truncated vanR activator gene (Figure 1). The difference between the VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R strain was a 44 bp deletion covering the inducible vanHAX promoter region in the resistant strain. Alternative promoters in the vanHAX promoter region were predicted in silico (P1 to P5 in Figure 1), but only promoters P1 to P3 changed their proximity to vanH, thus we predict these promoters to be responsible for the phenotypic reversion. The additional alternative promoters were also found in the prototypical vanA cluster of BM4147 (Figure S1). Promoter prediction solely in silico is a limitation of this study. However, we were unable to perform an experimental approach giving high enough resolution to distinguish putative promoters at the single nucleotide level, which would be required since the predicted promoters are overlapping.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the van cluster of VVESwe with the prototype. (Top) Pairwise alignment starting with the start codon up to bp 113 of the vanR gene of Tn1546 of BM4147 and the 5′-truncated vanR of VVESwe. Asterisks represent identity. (Middle) Pairwise alignment of the vanA cluster of Tn1546 of BM4147 and VVESwe-S. Both VVESwe isolates lack a functional vanR activator gene (light orange box). (Bottom) Pairwise alignment of the vanSH intergenic region of VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R. VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R comparisons revealed a 44 bp deletion in VVESwe-R, which is connected to direct repeat (DR) and inverted repeat (IR) sequences covering the inducible promoter region. Alternative promoters in VVESwe are marked with hexagons and numbered P1 to P5. Activator binding sites are indicated as boxes (VanR-P, VanR-phosphate binding site; RBS, ribosomal binding site). Light red shapes indicate which region of the van-cluster is zoomed in to. Red and blue bands between sequences represent forward and reverse complement matches, respectively.

The deletion occurred in a region with an IR and a DR and precisely removes one of the DR sequences as well as the nucleotides between the DR, which suggests that the deletion occurs by illegitimate recombination.29 Genome comparisons and read mapping with subsequent SNP and variation calling revealed no other obvious relevant genomic alterations that could be linked to the phenotypic differences between these isogenic strains, as shown in Table S3. The whole genome sequence of an additional independent revertant VVESwe-R (VVESwe-R2), was also compared with VVESwe-S and the same 44 bp deletion in the vanHAX promoter region was found (Table S3). Additionally, Sanger sequencing of the vanSH PCR product of two additional independent revertants showed the sequence to be identical to that in VVESwe-R.

To elucidate the observed difference in vancomycin susceptibility, we explored the localization and expression of vanHAX in the VVESwe-R isolate compared with VVESwe-S.

The vanA cluster in VVESwe is located on a plasmid

Genome sequence analysis revealed that the vanA cluster of VVESwe is located on a 35 kb non-conjugative plasmid (GenBank Acc. No. CP041279) with a rep previously described as a CDS1 putative replicon of the plasmid pRE25 belonging to Inc18 theta replicating plasmids of rep class 2.30 In other VVEs the vanA gene cluster localized on a transferable plasmid, which thus has a potential to spread vancomycin resistance.3,6,8 However, we were unable to show transfer of the vanA VVESwe-R in mating experiments.

The vanHAX-operon was constitutively expressed in VVESwe-R

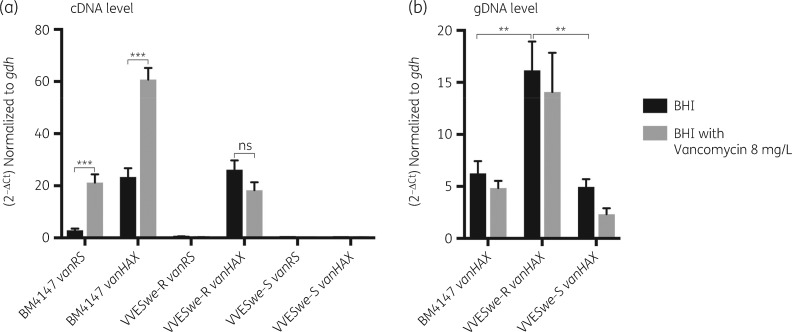

We examined the functionality of the alternative promoter in absence of the inducible promoter (Figure 1) by RT-qPCR on BM4147, VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R.

First, the transcription profile of the VanA-prototype strain BM4147 was analysed. Sanger sequencing of the vanSH PCR product confirmed that no genetic changes had occurred in Tn1546 of BM4147 compared with the reference sequence (GenBank Acc. No. M97297). Without vancomycin induction, BM4147 expressed vanRS and vanHAX (Figure 2a), in line with early studies at the protein level.31,32 This observation was also confirmed in MH broth, the standard medium for MIC testing (Figure S2). We therefore assume that in the absence of vancomycin induction, the above-described alternative constitutive promoters (Figure 1 and Figure S1) may be used for expression of vanHAX in BM4147, or low-level activation of the prototype promoter occurs.

Figure 2.

mRNA and gDNA levels of vanRS and vanHAX operons relative to the housekeeping gene gdh in BM4147, the susceptible (VVESwe-S) and resistant (VVESwe-R) isogenic VVE isolates grown in BHI broth without antimicrobials or in BHI broth with vancomycin 8 mg/L until mid-log phase. (a) Expression level as measured by RT-qPCR (t-test, two-tailed, PBM4147 vanRS < 0.0001, PBM4147 vanHAX < 0.0001, PVVESwe-R vanHAX = 0.141). (b) gDNA level as measured by qPCR (t-test, two-tailed, PBM4147 versus VVESwe-R = 0.0026, PVVESwe-R versus VVESwe-S = 0.0030). Bars are averages with SEM of three biological replicates including four technical repeats each.

Vancomycin exposure significantly increased the expression of both vanRS and vanHAX in BM4147, in line with the observed requirement of an intact vanRS for vancomycin induction of vanHAX (Figure 2a).32–34 The presence of vancomycin triggers phosphorylation of VanS, phospho-VanS then phosphorylates the transcriptional activator VanR and Phospho-VanR induces transcription of the vanHAX operon.35

The van-operon is considered as a textbook example of inducible resistance to glycopeptide antibiotics. Former studies observed that the regulatory expression of the vanHAX-operon is not tight, since VanA was detected in BM4147 membrane extracts even in the absence of vancomycin induction.31 Our data are consistent with previous studies, supporting the notion of an inducible prototypic vanA operon of Tn1546 and constitutive low-level expression of vanHAX in the absence of vancomycin induction.

The transcription profile of VVESwe showed very low expression of vanRS in both VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R, confirming non-functionality of vanRS in VVESwe, as predicted by sequence analysis. VVESwe-S does not express vanHAX, whereas VVESwe-R expresses vanHAX. The vanHAX-transcription level of VVESwe-R was similar with and without vancomycin exposure and comparable to the non-induced prototype BM4147-level (Figure 2a), supporting the notion of an alternative constitutive promoter. Constitutive expression of vanHAX has been described in Canadian VVE-R strains, but was due to a different set of mutations in the promoter region.5,6

Furthermore, the copy number of vanHAX at the gDNA level was measured in BM4147, VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R, in BHI both with and without vancomycin. Vancomycin exposure did not significantly alter the copy number of vanHAX in any strains. However, VVESwe-R harboured a higher copy number of the vanHAX-operon (16 ± 3), compared with both BM4147 (6 ± 1) and VVESwe-S (5 ± 1) (Figure 2b). A higher vanA-plasmid copy number may support higher expression levels of vanHAX from an alternative constitutive promoter, and thus in the absence of a functional vanRS may be responsible for the resistant phenotype. Moreover, both Illumina and Nanopore WGS analyses confirmed the plasmid copy number of the vanA-plasmids in VVESwe-R (n = 14) and VVESwe-S (n = 2). Similarly, vanA-plasmid copy number was described to confer reversion in an ST1421 strain.8 Recently, increased vanM gene cluster copy number by tandem amplification and increased expression was also described to confer resistance reversion36,37 but for the VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R nanopore assembly data showed that the vanA cluster appears as a single copy in the Inc18-plasmid.

In conclusion, an alternative promoter conveys vanHAX expression independent of the vanR activator and is thus not inducible by vancomycin. In addition, increased plasmid copy numbers add to the resistant phenotype.

The novel resistance phenotype posed a low fitness cost and was replaced by a susceptible phenotype over time

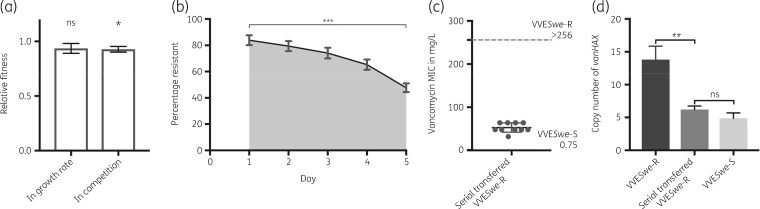

Acquisition of vancomycin resistance has been described to reduce the fitness of the resistant strain compared with its susceptible competitor in the absence of selective pressure.25,38,39 The relative fitness cost for the revertant VVESwe-R was low: 6% as measured by growth rate measurements and 9% in 24 h head-to-head competition experiments (Figure 3a). A comparable fitness cost of 4%–9% was previously described for strains possessing vanA-plasmids when compared with their plasmid-free counterpart.25,39

Figure 3.

Fitness and stability of the resistant revertant. (a) Relative fitness as assessed by growth rate and in head-to-head competition of VVESwe-S and VVESwe-R. Bars show mean with SEM of three biological replicates in three technical repeats each (t-test, two-tailed; ns, P = 0.1746; *P = 0.0134). (b) Stability of the VVESwe-R by serial transfer over 5 days. The plot shows mean with SEM of five biological replicates in three technical repeats each (t-test, two-tailed, ***P < 0.0001). (c) Vancomycin MIC (mg/L) of serial transferred VVESwe-R-colonies compared with VVESwe-R and VVESwe-S as measured with a MIC test strip. (d) Copy number of vanHAX normalized to gdh in VVESwe-R, VVESwe-S and serial transferred VVESwe-R-colonies measured by qPCR on gDNA isolated from the strains grown in BHI broth without vancomycin until mid-log phase. Bars show mean with SEM (t-test, two-tailed, **P = 0.0022; ns, P = 0.1766).

We further investigated the stability of the resistance phenotype under non-selective conditions where the vanA-plasmid would not be selected for. Over a period of 5 days the ratio of resistant colonies was reduced significantly to 50% (Figure 3b). Of note, the colonies were smaller on the vancomycin-containing plates compared with the plates without vancomycin after 24 h, and the plates were therefore re-checked after 48 h.

After serial transfer over 5 days, single colonies (n = 100) were collected and subjected to differential plating on BHI plates without and with vancomycin 8 mg/L. However, all 100 colonies were able to grow on vancomycin plates after 72 h, suggesting that even though the number of susceptible colonies read after 24 h had increased, these colonies had not lost vanHAX. Sanger sequencing of the vanSH PCR product of ten selected serial transferred colonies showed that no genetic changes had occurred compared with VVESwe-R. Illumina WGS analysis of two selected serial transferred colonies confirmed this. The vancomycin MIC of the ten selected serial transferred colonies ranged from 32–64 mg/L (Figure 3c).

The copy number of vanHAX under non-selective conditions was significantly reduced in serial transferred VVESwe-R compared with non-serial transferred VVESwe-R and at a similar level to the original VVESwe-S strain (Figure 3d). Thereby, the vanHAX-plasmid copy number combined with the promoter region deletion are likely responsible for the resistant phenotype and MIC variation of VVESwe-R. We hypothesize that this decrease of vanHAX-copy number also reduces the fitness cost of resistance and is therefore evolutionarily advantageous. Further experimental studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of plasmid copy number regulation.

In summary, we describe a VVE strain that can convert from a vancomycin-susceptible to a vancomycin-resistant phenotype and further to reduced resistance in response to differential vancomycin exposure. During vancomycin exposure the parental VVESwe-S strain converts to a VVESwe-R by a 44 bp deletion in the vanHAX-promoter region and an increased vanA-plasmid copy number (Figures 1 and 2). In the absence of vancomycin, the VVESwe-R population acquired a phenotype of a lower vancomycin MIC, which correlated to a decrease in vanA-plasmid copy number (Figure 3d).

In line with previous publications,5,6 we observed the ability of VVE to convert to a resistant phenotype during vancomycin selection. In a patient with a susceptible VVE infection, vancomycin would provide the selective pressure needed for selection and amplification of a resistant phenotype. Vancomycin is therefore not a treatment option for VVE. Years after the discovery of VVEs, a regional spread of VVE in Canada7 and a national spread of VVE in Denmark was reported,9 which highlights the importance of characterizing VVE clones and screening for their presence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Ellen H. Josefsen and Bjørg C. Haldorsen at the Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance for excellent technical assistance, Seila Pandur at the Institute for Chemistry, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, for genome sequencing using MiSeq, Hagar Taman at the Genomics Support Center Tromsø™, for genome sequencing using NextSeq500, Julia M. Kloos and Vidar Sørum at the Institute for Pharmacy, UiT The Arctic University of Norway, for advise on fitness experiments, and Petra Edquist, at The Public Health Agency of Sweden, for assistance with surveillance data.

Funding

This project was conducted at the Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance, Department of Microbiology and Infection Control, University Hospital of North-Norway, Tromsø, Norway and no other specific funding has been received for this study. This work was supported by travel grants from the National Graduate School in Infection Biology and Antimicrobials (grant number 249062). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Supplementary data

Tables S1 to S3 and Figures S1 and S2 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. Bender JK, Cattoir V, Hegstad K. et al. Update on prevalence and mechanisms of resistance to linezolid, tigecycline and daptomycin in enterococci in Europe: towards a common nomenclature. Drug Resist Updat 2018; 40: 25–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coburn B, Low DE, Patel SN. et al. Vancomycin-variable Enterococcus faecium: in vivo emergence of vancomycin resistance in a vancomycin-susceptible isolate. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52: 1766–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sivertsen A, Pedersen T, Larssen KW. et al. A silenced vanA gene cluster on a transferable plasmid caused an outbreak of vancomycin-variable enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 4119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arthur M, Depardieu F, Cabanié L. et al. Requirement of the VanY and VanX D, D-peptidases for glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Mol Microbiol 1998; 30: 819–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thaker MN, Kalan L, Waglechner N. et al. Vancomycin-variable enterococci can give rise to constitutive resistance during antibiotic therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 1405–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Szakacs TA, Kalan L, McConnell MJ. et al. Outbreak of vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecium containing the wild-type vanA gene. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52: 1682–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kohler P, Eshaghi A, Kim HC. et al. Prevalence of vancomycin-variable Enterococcus faecium (VVE) among vanA-positive sterile site isolates and patient factors associated with VVE bacteremia. PLoS One 2018; 13: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hansen TA, Pedersen MS, Nielsen LG. et al. Emergence of a vancomycin-variable Enterococcus faecium ST1421 strain containing a deletion in vanX. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73: 2936–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hammerum AM, Justesen US, Pinholt M. et al. Surveillance of vancomycin-resistant enterococci reveals shift in dominating clones and national spread of a vancomycin-variable vanA Enterococcus faecium ST1421-CT1134 clone, Denmark, 2015 to March 2019. Euro Surveill 2019; 24: 1900503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Folkhälsomyndigheten. Bilagor till VRE-diagnostiken - Referensmetodik för laboratoriediagnostik. http://referensmetodik.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/w/Bilagor_till_VRE-diagnostiken#Bilaga_3.

- 11. Simonsen GS, Myhre MR, Dahl KH. et al. Typeability of Tn1546-like elements in vancomycin-resistant enterococci using long-range PCRs and specific analysis of polymorphic regions. Microb Drug Resist 2000; 6: 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B.. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D. et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 2012; 19: 455–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 2068–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Seemann T. Scan contig files against traditional PubMLST typing schemes. https://github.com/tseemann/mlst.

- 16. Jünemann S, Sedlazeck FJ, Prior K. et al. Updating benchtop sequencing performance comparison. Nat Biotechnol 2013; 31: 294–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL. et al. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol 2017; 13: e1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li H, Durbin R.. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2010; 26: 589–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quinlan AR, Hall IM.. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010; 26: 841–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL. et al. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol 2004; 5: R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carver TJ, Rutherford KM, Berriman M. et al. ACT: the Artemis comparison tool. Bioinformatics 2005; 21: 3422–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA.. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 2011; 27: 1009–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Solovyev V, Salamov A.. Automatic annotation of microbial genomes and metagenomic sequences. In: Li RW, ed. Metagenomics and Its Applications in Agriculture, Biomedicine and Environmental Studies. Nova Science Publishers, 2011; 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee C, Kim J, Shin SG, Hwang S.. Absolute and relative QPCR quantification of plasmid copy number in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol 2006; 123: 273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Starikova I, Al-Haroni M, Werner G. et al. Fitness costs of various mobile genetic elements in Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68: 2755–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hall BG, Acar H, Nandipati A, Barlow M.. Growth rates made easy. Mol Biol Evol 2014; 31: 232–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wiser MJ, Lenski RE.. A comparison of methods to measure fitness in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 2015; 10: 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. König C, Simmen HP, Blaser J.. Bacterial concentrations in pus and infected peritoneal fluid–implications for bactericidal activity of antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother 1998; 42: 227–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rocha EPC. An appraisal of the potential for illegitimate recombination in bacterial genomes and its consequences: from duplications to genome reduction. Genome Res 2003; 13: 1123–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mikalsen T, Pedersen T, Willems R. et al. Investigating the mobilome in clinically important lineages of Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. BMC Genomics 2015; 16: 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dutka-Malen S, Mohnas C, Arthur M, Courvalin P. The VANA glycopeptide resistance protein is related to d-alanyl-d-alanine ligase cell wall biosynthesis enzymes. Mol Gen Genet 1990; 224: 364–72. 10.1007/BF00262430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Arthur M, Molinas C, Courvalin P.. The VanS-VanR two-component regulatory system controls synthesis of depsipeptide peptidoglycan precursors in Enterococcus faecium BM4147. J Bacteriol 1992; 174: 2582–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arthur M, Reynolds PE, Depardieu F. et al. Mechanisms of glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. J Infect 1996; 32: 11–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arthur M, Depardieu F, Gerbaud G. et al. The VanS sensor negatively controls VanR-mediated transcriptional activation of glycopeptide resistance genes of Tn1546 and related elements in the absence of induction. J Bacteriol 1997; 179: 97–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Courvalin P. Vancomycin resistance in Gram-positive cocci. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42: S25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou Y, Yang Y, Ding L. et al. Vancomycin heteroresistance in vanM-type Enterococcus faecium. Microb Drug Resist 2020; 26: 776–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sun L, Chen Y, Hua X. et al. Tandem amplification of the vanM gene cluster drives vancomycin resistance in vancomycin-variable enterococci. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020; 75: 283–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Foucault ML, Courvalin P, Grillot-Courvalin C.. Fitness cost of VanA-type vancomycin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53: 2354–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnsen PJ, Simonsen GS, Olsvik Ø. et al. Stability, persistence, and evolution of plasmid-encoded VanA glycopeptide resistance in enterococci in the absence of antibiotic selection in vitro and in gnotobiotic mice. Microb Drug Resist 2002; 8: 161–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.