Abstract

Radiotherapy with or without surgery is a common choice for brain tumors in dogs. Although numerous studies have evaluated use of three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy, reports of definitive-intent, intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for canine intracranial tumors are lacking. IMRT has the benefit of decreasing dose to nearby organs at risk and may aid in reducing toxicity. However, increasing dose conformity with IMRT calls for accurate target delineation and daily patient positioning, in order to decrease the risk of a geographic miss. To determine survival outcome and toxicity, we performed a multi-institutional retrospective observational study evaluating dogs with brain tumors treated with IMRT. Fifty-two dogs treated with fractionated, definitive-intent IMRT at four academic radiotherapy facilities were included. All dogs presented with neurologic signs and were diagnosed via magnetic resonance imaging. Presumed radiological diagnoses included 37 meningiomas, 12 gliomas, and 1 peripheral nerve sheath tumor. One dog had two presumed meningiomas and one dog had either a glioma or meningioma. All dogs were treated in the macroscopic disease setting and were prescribed a total dose of 45–50 Gy (2.25–2.5 Gy per fraction in 18–20 daily fractions). Median survival time for all patients, including seven cases treated with a second course of therapy was 18.1 months (95% CI 12.3–26.6 months). As previously described for brain tumors, increasing severity of neurologic signs at diagnosis was associated with a worse outcome. IMRT was well tolerated with few reported acute, acute delayed or late side effects.

Keywords: IMRT, conformity, canine, IGRT

Introduction

Conventional, fractionated radiation therapy (RT) with or without surgery is the treatment of choice for brain tumors in dogs1–2. Two studies have evaluated the use offinely fractionated (≤ 3 Gy per fraction), three-dimensional, conformal radiotherapy (3DCRT) without surgery with median survival times of 19 – 23 months1–2. The total prescribed dose in these studies ranged from 35 – 54 Gy. Dose per fraction varied between 2.5 – 3 Gy per fraction. Acuteradiation side effects (ocular, oral, aural) wereseen in 45% of dogs in one study2 and were not mentioned in the other study1. Reported late side effects were absent in one study1 and found in 23% in another2; late side effects were only seen at a low frequency, characterized by grade 1 skin, CNS and ocular effects2.Late side effects may be underreported in these studies due to a lack of standardized follow-up.

Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT)can result in a greater degree ofdose conformityand a steeper dose gradient outside of the target when compared to 3DCRT3. This feature can be used to selectively reduce dose of ionizing radiation to nearby organs at risk3. In consequence, side effectsmay decrease and the quality of life of the patient improves4–5. However, the increasing conformity of IMRT calls for accuratetarget delineation and confirmation of daily patient positioning. Errors in positioning and inaccuracies or misconceptions of the extent of tumor infiltration have the potential to increase the risk of a geographic miss compared to less conformal 3DCRT6–7. Accurate target contouring is especially important, as canine meningiomas have been reported to be more invasive than their human counterparts8.Additional concerns arise with the use of IMRT. Integral dose, or the volume integral of the dose deposited in the patient, rises with certain IMRT techniques, especially with helical delivery systems such as Tomotherapy, and increased integral dose might be related to a higher risk of secondary cancers9–11. There is also increased cost and time needed for planning and delivery of IMRT compared to 3DCRT12.

There has been an increase in use of IMRT for the treatment of canine brain tumors, but the true clinical benefit, if any, of IMRT over 3DCRT when conventionally fractionated protocols are used is not known. Although there are numerous publications investigating the use of 3DCRT and SRT for canine brain tumors, there is no data reporting outcome and toxicity of conventionally fractionated IMRT. We hypothesized that dogs treated with conventionally fractionated, definitive intent IMRT for brain tumors would have a similar to improved outcome with comparable side effects compared to dogs treated with definitive-intent 3DCRT.

Methods and Materials

This was multi-institutional retrospective observational study. The medical records of dogs with primary brain tumors treated with definitive intent IMRT with image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT) at the veterinary teaching hospitals of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, University of Zurich, University of Guelph and The Ohio State University were retrospectively reviewed during the period of 2011 to 2018. This study was retrospective, so it was not approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Permission for use of the medical record data was provided by the hospital director. Inclusion criteria consisted of treatment with definitive-intent, conventionally-fractionated radiation therapy (18–20 fractions) for a primary, non-pituitary intracranial neoplasm diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An ACVR-certified radiation oncologist from each institution evaluated each dog for inclusion in the study. Dogs were included in the study on an intent-to-treat basis such that all dogs that began radiotherapy were included in the analysis regardless of whether they completed treatment. Dogs with primary pituitary masses, previously surgically debulked/excised intracranial tumors, suspected round cell or metastatic tumors, and dogs with inadequate follow-up (no recheck examinations or contact with the treating hospital after the end of radiation therapy) were excluded. Data recording was based on each independent radiation oncologist. Pituitary masses were excluded as previous literature has demonstrated a disproportionate outcome compared to other intracranial tumors1. Participating radiation oncologists were provided data extraction forms that requested information about signalment, presenting neurologic signs, pre-treatment laboratory work, staging results (thoracic and abdominal imaging), pre-treatment medications, concurrent diseases, tumor type, method of diagnosis, tumor imaging, tumor localization (supratentorial, infratentorial), radiation delivery system and technique, radiation prescription, radiation dose statistics, patient positioning methodology, radiation side effects, follow up visits, any documented clinical or imaging response to radiation, additional radiation treatments, neurologic progression, cause of death and date of death or euthanasia. Follow-up information was obtained from medical records as well as phone calls to the primary veterinarians and owners. Grade of neurologic signs was assigned retrospectively by the primary author and defined according to a previously published protocol: grade 1 (i.e. seizures only or mild neurologic signs), grade 2 (moderate to marked neurologic signs) and grade 3 (stupor or non-ambulatory)13.

The radiation treatment plan of each patient was reviewed by the participating radiation oncologist from the institution where the patient was treated. Each institution had its own methods for optimization and setting of constraints (i.e. brain minus GTV or brain minus PTV). For reporting purposes, brain volume was defined as the volume of the brain including the GTV.Dose statistics for target volumes (GTV, CTV, PTV) were recorded, including median dose (D50%), D2%, D98% and D95%3, 14.Organ at risk statistics were recorded for the brain, specifically D2% and Dmean3, 14. Dose homogeneity and conformity calculations were based on the RTOG conformity index, van’t Reit conformity index, and homogeneity index (Table 1)15.

Table 1.

Various indices used for plan evaluation.

| RTOG Conformity Index | |

| van’tReit Conformity Index | |

| Homogeneity Index | |

TVRI = Target volume (PTV) covered by the reference isodose. TV = Target volume (PTV). VPI = Volume of prescription isodose.

Clinical improvement of neurologic signs was reported based on available documentation in the medical records. Objective tumor response was assessed via imaging (MRI) and tumor response criteria were not standardized due to the retrospective nature of this study. Centralized imaging review was not performed. Tumor response was considered complete if the tumor was described as having disappeared on follow up imaging. Tumors that persisted on follow up imaging but measured smaller in size compared to before treatment were classified as having a measurable response. Progressive disease was reported if neurological signs worsened due to radiation side effects or tumor enlargement based on MRI. If the tumor responded but the dog exhibited progressive neurologic signs, this was defined as progressive disease. Stable disease was reported if the tumor size did not change. Acute side effects (occurring within 90 days of radiation therapy) and late side effects (occurring > 90 days after radiation therapy)were graded according to the Veterinary Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (VRTOG) radiation morbidity scoring scheme16. Information regarding acute side effects was retrospectively evaluated in all cases. If there was no mention of side effects in the medical record, the patient was presumed to have had no side effects. Acute delayed side effects were defined as having occurred between 1 – 3 months after radiation therapy. Late side effects were reported if confirmed via necropsy, suspected on imaging or suspected by the participating radiation oncologist based on interpretation of the medical record.

Statistics

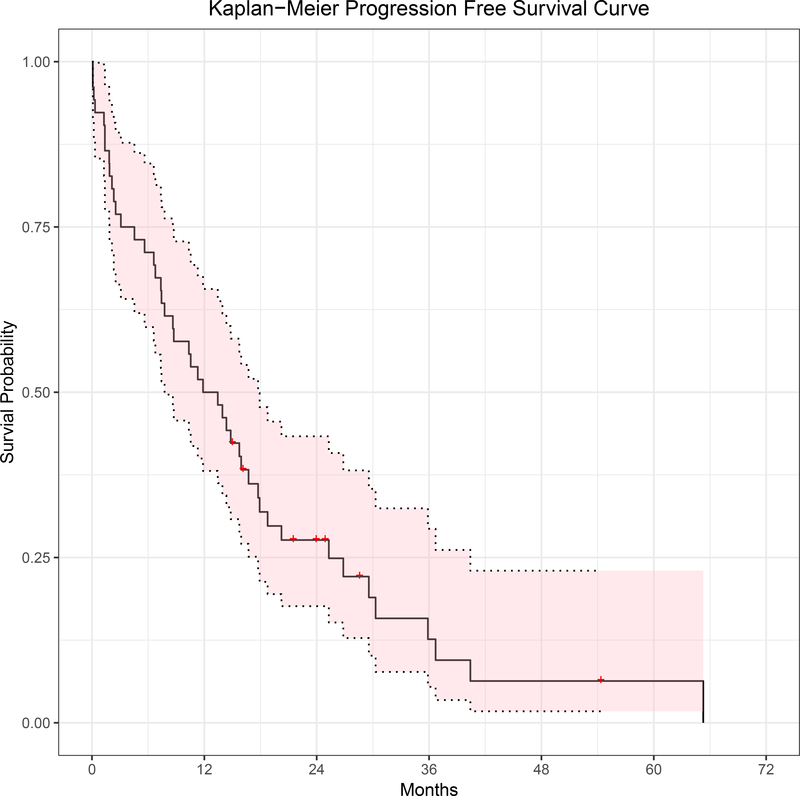

Statistical analyses were performed by a biostatistician (YC) using statistical computing freeware (R version 3.4.2, https://www.r-project.org/) including the “survival” and “survminer” packages. Variables were summarized by N (%), mean (SD), or median (IQR) when appropriate based on variable distribution. Overall survival (OS) was defined by the date of initiation of radiotherapy to date of death from any cause. Dogs that were alive at the end of the study or lost to follow up were censored at the date of last available follow-up (hospital visit or phone call with owner or primary veterinarian). Progression free survival (PFS) was defined by the date of initiation of radiotherapy to the date of documented clinical neurologic progression, progression on imaging or death from any cause, whichever came first. Dogs that were alive and without evidence of progression were censored for PFS analysis at the date of the last evaluation. OS and PFS were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and median OS, PFS were computed with associated 95% confidence interval. Median follow up time was calculated for dogs censored. Cox Proportional Hazard model was used to assess the effect of the following prognostic factors: grade of neurologic signs (grade 1 vs. 2+3), tumor location (infratentorial vs. supratentorial), PTV to brain volume ratio and tumor type (meningioma, glioma) on OS. Grade 2+3 were grouped together to allow for more robust statistical evaluation as there was onlyone dog with grade 3 neurologic signs. All statistical tests were two-sided, and 5% (p<0.05) was set as the level of significance.

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 52dogs were treated during the sample period and included in analyses. Twenty dogs were from the Ontario Veterinary College, 17 from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, 12 from the University of Zurich and 3 from The Ohio State University.Signalment, age, weight, diagnosis, location and grade are included in Table 2. All brain tumors were presumptively diagnosed based on interpretations of MRI findings by board certified radiologists. Biopsies were not performed to confirm diagnosis before treatment in any case. A portion of the dogs (8) in this study population were included in a previous publication17.

Table 2.

Descriptive summary statistics reported as N (%), mean (SD).

| Variable | N = 52 |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (yrs) | 9.4 (2.4) |

| Sex – female (23 spayed, 2 intact) | 25 (48.1%) |

| Sex – male (23 neutered, 4 intact) | 27 (51.9%) |

| Weight (kg) | 24.3 (12.7) |

| Presumed tumor type | |

| Glioma | 12 (23.1%) |

| Meningioma | 38 (73.1%) |

| PNST (Large brainstem component) | 1 (1.9%) |

| Glioma or meningioma | 1 (1.9%) |

| Location | |

| Infratentorial | 18 (34.6%) |

| Supratentorial | 32 (61.5%) |

| Both Intratentorial and Supratentorial | 2 (3.8%) |

| Neurological Grade | |

| 1 | 32 (62.7%) |

| 2 and 3 | 19 (37.3%) |

PNST: peripheral nerve sheath tumor. Two dogs had concurrent incidental pituitary tumors that were not considered to be the primary cause of the dog’s clinical signs.

All dogs presented with neurologic signs. Presenting signs included seizures (30), cranial nerve deficits (25), gait abnormalities (21), change in behavior (17), inappetence (6), decreased alertness /obtundation (6), and blindness (3). A total of 32 dogs presented with grade 1 neurologic signs (including 2/3 blind dogs), 18 with grade 2 (including 1/3 blind dogs) and 1 with grade 3. Grade was not available in one dog. There was no statistically significant difference in cancer type by grade with Glioma rate in grade 1 (5/30 [16.7%]) vs grades 2&3 (7/19 [36.8%]; p=0.173). There was also no statistically significant difference in PTV: Brain ratio by cancer type with median (IQR) of the ratio in glioma subjects being 0.22 (0.14, 0.36) compared to 0.20 (0.10, 0.32) in meningioma subjects (p=0.351).All dogs except for two were prescribed prednisone at the time of diagnosis resulting in neurologic improvement in thirty-seven dogs. Prednisone use did not improve neurologic signs in 10 dogs and change in neurologic signs were unknown in 5 dogs.

Thoracic imaging (computed tomography (CT) or radiography) was performed in all but one dog, abdominal imaging (CT or ultrasound) was performed in 44 dogs, and pre-anesthetic bloodwork was performed in all dogs. The technical parameters and equipment used for these diagnostic imaging testswere not recorded. No significant co-morbidities were diagnosed at the time of radiotherapy in any case.

Radiation Therapy

Treatment planning CT scans were performed for each patient in the treatment position. Treatment position consisted of sternal recumbency using an immobilization system specific to each institution, including a customized bite block and vacuum mattress in all cases. The bite block systems were designed and validated at their respective institutions.Brain CT Scans were performed using the following helical CT scanner: GE Bright Speed 16-slice (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA), GE Light Speed 64-slice (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA), Philips 16 Brilliance 16-slice (Philips AG, Zurich, Switzerland) and GE Lightspeed 8-slice (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA). Brain MRI scans were performed using the following machines: Philips Inguinia 3T (Philips AG, Zurich, Switzerland), Philips Inguinia 3T (Philips, Cleveland, Ohio, USA), GE Sigma 1.5T (GE Healthcare Canada, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and GE Sigma 1.5T (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA). In some patients, MR-studies from the referring neurologists were used / imported for contouring. Contours were drawn on 3-dimensional computed tomography, co-registered with MRI in 47 / 52 cases. Thickness of CT slices varied between 0.6 – 2 mm, while both slice thickness and gap thickness on MRI varied between 0.6– 5.5 mm. Gross tumor volume (GTV) was contoured as contrast enhancing tumor on CT, adapted accordingly if fused with MRI. Clinical target volume (CTV) varied between 0–5 mm in most dogs, while some institutions only included a CTV that encompassed edema if it was present on the T2/Flair MRI sequences (16 dogs). Determination of the CTV margin was influenced by a number of factors, including imaging findings (Ill-defined vs well-defined), tumor location and patient size, among others. These factors varied between institutions. Planning target volume (PTV) varied between 1–3 mm. Forty-three dogs had a PTV of 2 mm, six dogs had a PTV of 3 mm and two dogs had a PTV of 1 mm. The PTV expansion was not available in one dog but was suspected to be 2 mm. Inverse planning with heterogeneity corrections was performed using the Eclipse Treatment Planning system (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA; Versions 10.0, 11.5, 13 and 13.06; AAA algorithm) at all sites except the University of Wisconsin-Madison where IMRT was planned using the Tomotherapy Planning Station Hi-Art system (Accuray Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA; Versions 3 to 5; convolution superposition algorithm).

The treatment planning goal at all institutions was to deliver at least 95% of the prescribed dose to 95% of the PTV while minimizing dose to normal tissues, with some institutions aiming for greater target coverage. Optimization was performed in all institutions using dose volume cost functions. One institution employed equivalent uniform dose (EUD) and a second employed an in-house normal tissue complication probability (NTCP)calculator18. All plans were evaluated and approved by an American College of Veterinary Radiology (ACVR) certified radiation oncologist. Quality analysis was performed for all plans and consisted of film and a point measurement via ion chamber at one institution, film at another institution, ionization chamber array at the third institution and electronic portal imaging device (EPID) dosimetry verification at the fourth institution.

All facilities used 6 MV photons beams. Three facilities delivered radiation with 4–9 isocentric, static, coplanar gantry angles using either static (step and shoot, n=1) or dynamic (n = 2) IMRT. These facilities used conventional C-arm linear accelerators including Siemens Oncor™ Digital Linear Accelerator (Siemens Medical Laboratories, Walnut Creek, CA), Varian Clinac 2300 iX and ClinaciX (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). The fourth facility delivered radiation using a helical tomotherapy unit (Accuray Inc., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) unit. All patients had daily on-board imaging performed before treatment delivery (megavoltage computed tomography (MVCT, 17 dogs), kilo voltage (kV) cone beam CT (kVCBCT, 23 dogs), orthogonal kV images (9 dogs) or a combination of kVCBCT or orthogonal kV images (3 dogs). Dogs were prescribed a total dose of 45 – 50 Gy delivered in daily fractions on a Monday to Friday schedule [2.5 Gy x 20 (n = 38), 2.4 Gy x 20 (n = 3), 2.25 Gy x 20 (n =2), 2.5 Gy x 18 (n = 9)]. Radiation dose statistics are listed in Table 3. Dose conformity and homogeneity indices are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Median (SD) target and organ at risk volumes and dose statistics.

| Target Volume (cm3) | Brain Volume (cm3) and Dosimetry (Gy) Data | ||||||||

| GTV | CTV | PTV | Prescription Isodose Volume | Volume | D2% | Dmean | |||

| 2.8 (4.61) | 9.2 (11.9) | 16.4 (16.87) | 13.58 (14.02) | 82.6 (25.62) | 50.76 (3.53) | 21.38 (15.3) | |||

|

Target Dosimetry (Gy) Data | |||||||||

| GTV | CTV | PTV | |||||||

| D50% | D98% | D2% | D50% | D98% | D2% | D50% | D98% | D2% | D95% |

| 50.44 (2.83) | 49.69 (2.8) | 51.06 (1.92) | 50.43 (2.69) | 49.6 (2.99) | 51.36 (2.69) | 50.42 (2.75) | 47.41 (4.54) | 51.29 (2.4) | 48.31 (4.24) |

Table 4.

Median (IQR) conformity and homogeneityindices along with delivery type.

| Conformity (RTOG) | Conformity (van’tReit) | Homogeneity | Delivery Type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 0.85 (0.37) | 0.70 (0.19) | 1.06 (0.03) | |

| University of Guelph | 0.71 (0.16) | 0.66 (0.19) | 1.07 (0.02) | Dynamic MLC |

| The Ohio State | 1.00 (0.15) | 0.83 (0.12) | 1.08 (0.01) | Static MLC |

| University of Wisconsin | 1.05 (0.08) | 0.79 (0.05) | 1.04 (0.01) | Tomotherapy |

| University of Zurich | 0.69 (0.27) | 0.56 (0.20) | 1.05 (0.04) | Dynamic MLC |

Two patients had deviations to the intended radiation protocol. One patient experienced a one-week treatment delay due to mechanical failure of the treatment machine after receiving 5 fractions of 2.5 Gy. This patient received an additional 14 fractions of 3.2 Gy. Another patient missed the first fraction of radiation, so this patient was given 19 fractions of 2.63 Gy. Four dogs (8%) died during radiotherapy. One dog died while being anesthetized prior to the tenth radiation fraction. Another dog died six days after starting radiation, with the cause of death suspected to be due to marked aspiration pneumonia. The third dog was euthanized three days after treatment start due to dull mentation and progressive clinical signs during treatment that were not responsive to supportive medications. The fourth dog was euthanized three days after starting radiation therapy due to worsening neurologic status in the face of treatment.

Clinical Response to Treatment

Thirty-nine dogs (75%) improved neurologically during or shortly after radiation therapy. Many of these patients received prednisone, potentially confounding the effect of radiation on neurologic improvement. Four dogs displayed stable neurologic signs during and after treatment for an overall clinical benefit of 83% (43 / 52). Information about the duration of prednisone use, such as duration of use or dosage, was not obtained.

Seventeen dogs had recheck MRI or CT’s performed after radiotherapy. The reason for re-imaging was not obtained and likely varied between evaluations of tumor size as a regular recheck versus progressive neurologic signs. Ten of the re-imaged dogs had measurable responses, one being a complete response (range of 3 to 16 months). Two dogs diagnosed with gliomas had presumed intraventricular metastasis at 3 and 6 months post radiation. One patient had a measurable response on imaging 26 months after treatment but was clinically progressive with worsening neurologic signs. Four dogs had a measurable response at 4 to 15 months and went on to develop progressive disease 3 to 7 months later.

Follow up and Survival

Eight dogs were still alive at the time of analysis and three were lost to follow up. Median time to follow up in the surviving animals was 24 months (IQR of 18.7, 26.1).Twenty-five(27 / 52) dogs died due to worsening neurologic status. All four dogs who died during radiation treatment were presumed to have died due to neurologic disease and are included in this number. Information regarding neurologic progression and cause of death was not available in seven dogs so progression free survival was able to be determined in 45 dogs. Fivedogs died without neurologic progression due to other causes (osteosarcoma, zinc toxicity, histiocytic sarcoma, aspiration pneumonia 1 month after completion of radiation therapy, and severe hind limb arthritis) whereas one died after neurologic progression due to a large liver mass. One dog presented for cough and subcutaneous mass on the lateral thorax as well as pulmonary metastatic disease 9 months after being treated for a presumed meningioma. No sampling of the subcutaneous mass or pulmonary metastatic disease was performed. This dog had yet to neurologically progress after treatment. Of the 8 animals still alive at the time of analysis, three had progressive disease and 5 were alive without evidence of progression. Progression of neurologic signs was correlated with progression on imaging (MRI) in six cases.

Median OS for all patients was 18.1 months (95% CI: 12.3 – 25.3 months). Median PFS was 12.7 months (95% CI: 7.8 to 17.7 months). Higher grade of neurologic signs (grade 2+3 vs grade 1) (P = 0.021) was significantly associated with a worse outcome (Table 5).

Table 5.

Cox proportional hazard model hazard ratio on variables. Hazard ratio reported as change per 0.1 units.

| Cox model covariates | Variables | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution | Institution | Guelph (reference) | ||

| OSU | 0.49 [0.06, 3.74] | 0.491 | ||

| UW | 1.35 [0.64, 2.87] | 0.435 | ||

| Zurich | 0.91 [0.41, 2.03] | 0.815 | ||

| Institution + Grade | Grade | Grade 1 (reference) | ||

| Grade (2&3) | 2.45 [1.20, 4.97] | 0.0135 | ||

| Institution + Tumor | Tumor | Giloma (reference) | ||

| Meningioma | 0.63 [0.28, 1.41] | 0.263 | ||

| Institution + Location | Location | Infratentorial (reference) | ||

| Supratentorial | 0.89 [0.44, 1.83] | 0. 756 | ||

| Institution + Target/Brain Volume Ratio (X10) | Target/Brain Volume Ratio (unit=0.1) | 1.24 [0.98, 1.58] | 0.0723 | |

| Institution + Conformity (RTOG) | Conformity (RTOG) (unit=0.1) | 1.06 [0.88, 1.28] | 0.559 | |

| Institution + Conformity (van’t Riet) | Conformity (van’t Riet) (unit=0.1) | 1.04 [0.82, 1.34] | 0.727 | |

| Institution + Homogeneity | Homogeneity (unit=0.1) | 1.04 [0.24, 4.57] | 0.955 | |

| Institution + Coregistration | Coregistration | Yes | 1.37 [0.42, 4.5] | 0.60 |

| No (Reference) |

Eight dogs received additional treatments after developing progressive neurologic signs and / or imaging findings suspicious for tumor progression. Seven dogs were retreated with radiation. Radiation protocols consisted of the following: 3 fractions of 5 Gy (2 dogs; Monday Wednesday, Friday), 3 fractions of 8 Gy (Monday, Wednesday, Friday), 14 fractions of 2.2 Gy (consecutive), 10 fractions of 3 Gy (2 dogs, consecutive) and 5 fractions of 4 Gy (consecutive). One dog was treated with oral chemotherapy (CCNU). Clinical response was available for one dog whose neurologic signs completely resolved and who lived for another 27 months (14 fx x 2.2 Gy). Response to therapy was not available for the other dogs that received additional treatments.

Adverse Effects

Overall, acute side effects were reported in 3 / 54 dogs (5.5%) and, when reported, were self-limiting. Reported acute side effects consisted of one possible grade I aural complication characterized by a waxy external horizontal ear canal occurring two weeks after radiation, one possible acute delayed grade 1 neurologic sign characterized by mild ataxia occurring 47 days after the end of radiation therapy that resolved with corticosteroid administration, and one possible acute grade 1 episode consisting of loss of balance, confusion and delayed proprioception.

Late side effects were also minimal, with no clear late side effects reported. The possibility of late brain effects cannot be ruled out in the group of twenty-nine dogs that had neurologic progression. Postmortem examinations were performed on 7 dogs, six of which had available records. Of the six dogs with histopathologic information, the imaging diagnosis was confirmed in five dogs while one had an undifferentiated tumor that was originally diagnosed by MRI as either a glioma or meningioma. None of the gross or histopathologic descriptions were indicative of late radiation side effects.

Discussion

This study’s aim was to evaluate the survival outcome and side effect profile of fractionated, definitive-intent IMRTin dogs with brain tumors from four veterinary institutions. The median survival of 18.1 months (543 days) is in line with previously published studies that used definitive intent 3DCRT1–2, 19.Rohrer Bley et al reported a median survival time for dogs treated with conventionally fractionated 3DCRT of 23.3 months (95% CI, 19.6 – 27 months), or 39.1 months (95% CI, 23.1 – 55.2 months) when death was attributed to tumor-related causes1. In a study by Keyerleber et al., the median survival timewas19.2 months (IQR = 9.1 – 27.6months) while a study by Treggiari et al found a median survival time 25.2 months (95% CI 7 – 43.4 months) in dogs with infratentorial brain tumors2, 19. However, it is difficult to compare retrospective studies, due to variable delivery techniques, fractionation protocols, follow-up and diagnostics.

In physician-based medicine, there is ongoing discussion as to the efficacy of IMRT for tumor control since the technique itself does not enhance prescribed dose and therefore may not improve tumor control probability4, 20.Rather, due to the steeper dose gradients and potentially smaller margins, the risk for geographic miss theoretically could be more likely. In studies of head and neck tumors in people, when an increase in locoregional control is found with IMRT, it is confounded by the concurrent use of intense chemotherapeutic regimens20. There is minimal literature concerning the effect of IMRT on locoregional control of intracranial tumors in people. In one study, there was no survival advantage with IMRT compared to 3DCRT in a population of glioblastoma patients4.

Acute side effects in our study were minimal. Some acute side effects that were reported were questionably associated with radiation therapy (one dog displayed waxy horizontal ears canals), however reduced side effects may be an important ethical consideration in veterinary patients and a potential benefit of IMRT in veterinary patients. Reported late side effects were minimal as well, however these may have been underreported due to the lack of imaging or necropsy in dogs with progressive neurologic signs. In people with intracranial tumors, the effect of IMRT on side effects is not clear. One publication suggested that IMRT decreased the incidence of grade 1 and 2 neurological toxicities compared to 3DCRT4. The decrease in side effects brought about by IMRT is more appreciable and reproducible in the cases of xerostomia and dental disease in head and neck patients21–22. The disparity between the impact of IMRT in head and neck patients vs. brain tumor patients with respect to reducing side effects could be explained by the high tolerability of normal brain tissue to conventionally fractionated radiation prescription resulting in minimal toxicity even when less conformal techniques are used.

Dogs with more severe neurologic signs (grade 2, 3) had a significantly worse outcome than dogs with grade 1 neurologic signs. Neurologic status has previously been found to be a significant prognostic factor17. As with most veterinary studies grade was assigned retrospectively based on record review which may lead to inaccuracies. Although it has been previously suggested that gliomas have a more aggressive biologic behavior and inferior outcome compared to other tumor types17, tumor type based on imaging diagnosis was not associated with outcome in the present study.

There was a wide variation in the dose conformity delivered at the four institutions involved in this study (Table 4). Generally, RTOG conformity index of 1 indicates that the target volume and the volume of tissue receiving the prescription radiation dose are the same (irrespective of overlap) and a van’t Reit value of > 0.8 indicates good conformity of the prescription iso dose volume to the target volume. The importance of high dose conformity when using conventionally fractionated radiotherapy protocols for brain tumor irradiated is not defined. As mentioned above, conformity may be less important than in other areas of the body due to the high tolerance of normal brain tissue to low doses of radiation per fraction. Conventionally fractionated radiation treatments using less-conformal 3DCRT have been shown to be safe in dogs with brain tumors, with minimal acute or late side effects documented in the literature1–2. Achieving a high conformity index, therefore, may not have been a treatment planning priority at all institutions in this study. Conformity index can also be affected by treatment planning strategies that prioritize sparing of normal brain over less critical adjacent tissues; for example, some treatment planners may accept dose spill off into adjacent bone and muscle in order to obtain high conformity with sharp dose fall off in surrounding normal brain (such as brain stem).Therefore, the wide variation in conformity indices between institutions reported in this study may be the result of a number of factors, including different optimization goals, different treatment planning strategies, as well as different radiation delivery systems. Determining what role, if any, IMRT has in tumor control and probability of side effects in brain tumor irradiation compared to3DCRT (forward-planning) techniques when conventionally fractionated protocols are used requires further investigation.

The homogeneity index varied between institutions suggesting that some institutions accepted greater maximal radiation doses within the tumor. While this could theoretically impact outcome, the degree of dose heterogeneity was less than 15% above the prescribed dose in almost all cases, which is considered within the range of uniform dosing. When aiming for very conformal dose delivery and sharp fall off, IMRT optimization can require dose heterogeneity within the tumor. Thus, while it was common to aim for a uniform dose distribution with 3DCRT in the past, this is nowadays sometimes questioned as it limits the freedom of the optimizer to achieve highly conformal dose distributions with IMRT23.

The total dose delivered in this study (45 – 50 Gy) may not be high enough to provide adequate tumor control, however if an for normal brain tissue of 2 or 3 is assumed, 50 Gy in 20 fractions is an EQD2 of 55 – 56.25 Gy which approaches the tolerance doses for the brainstem and optic pathway of 55–60 Gy reported in QUANTEC28.This prescription varied across the facilities and was dependent on clinician experience and comfort level. IMRT’s greater conformity enables dose escalation within the target, such as with hypofractionated or stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT)24. Stereotactic radiation therapy has been increasingly utilized in veterinary medicine for the treatment of intracranial tumors25–27. Reported survival times have range between 13.3 – 18.7 months25–27, with one publication noting an increase in acute delayed radiation side effects26. To combat the risk of side effects, recent literature has been published evaluating more moderately hypofractionated protocols for brain tumors17–18.

There was a limited opportunity to assess tumor response in this study, as follow up imaging was not routinely performed and was performed at various time points along disease progression. Owners elected to reimage either during routine rechecks or upon progression of neurologic signs. In cases where a response was seen, response criteria were not standardized. This is an unfortunate but accepted reality of retrospective studies in veterinary oncology. Objectively assessing tumor response was not the primary goal of this study.

Limitations of this multi-institutional retrospective study included a small sample size, lack of standardized follow up information, lack of standardized brain imaging methods, and lack of histopathologic diagnosis of brain tumors. Contouring techniques were also not standardized; CTV and PTV were defined differently among institutions and even among individuals at the same institution, which could skew the prognostic value of factors such as PTV/brain ratio. In addition, brain was assessed as an OAR to include GTV. Treatment planning goals were not standardized, and different radiation delivery systems were used, impacting the degree the dose conformity and homogeneity. The date of progression was requested in the data extraction forms however this information was not available in a large proportion of dogs. Additionally, assessment of tumor progression is not always clear when retrospectively reviewing data. Consequently, the estimated progression free survival may not represent the true time to progression in this population of dogs. Lack of standardized follow-up is a major limitation when evaluating radiation toxicity.

Findings from this study indicated that median survival time of dogs with brain tumors treated with definitive-intent IMRT at four U.S. veterinary institutions was consistent with previous reports of less-conformal 3DCRT. An advantage of IMRT is ahigh degree of dose conformity, which enables dose escalation and the opportunity to perform hypofractionated treatments17. A prospective clinical study with standardized techniques and follow-up is required to confirm any benefits or limitations of IMRT compared to 3DCRT.

Figure 1.

Overall Survival. Median OS for all patients was 18.1 months (95% CI: 12.3 – 25.3 months).

Figure 2.

Progression Free Survival. Median PFS was 12.7 months (95% CI: 7.8 to 17.7 months).

Acknowledgements:

The project was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR002373. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations:

- IMRT

Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy

- IGRT

Image Guided Radiation Therapy

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

EQUATOR network disclosure: This study followed the EQUATOR STROBE-VET reporting guidelines.

Previous presentation or publication disclosure: The results of this study were presented as a poster at the American College of Veterinary Radiology conference in October 2018.

References

- 1.Rohrer Bley C, Sumová A, Roos M, Kaser-Hotz B. Irradiation of brain tumors in dogs with neurologic disease. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2005. December 17;19:849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keyerleber MA, McEntee MC, Farrelly J, Thompson MS, Scrivani PV, Dewey CW. Three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy alone or in combination with surgery for treatment of canine intracranial meningiomas. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2013. July 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements: Report 83. Journal of the ICRU. 2010;10:NP.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thibouw D, Truc G, Bertaut A, Chevalier C, Aubignac L, Mirjolet C. Clinical and dosimetric study of radiotherapy for glioblastoma: three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy versus intensity-modulated radiotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2018. January 27;137:429–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vergeer MR, Doornaert P, Rietveld D. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy reduces radiation-induced morbidity and improves health-related quality of life: results of a nonrandomized prospective study using a standardized follow-up program. Int J RadiatOncBiol Phys 2009. May 1:74(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakraborty S, Patil VM, Babu S, Muttath G, Thiagarajan SK. Locoregional recurrences after post-operative volumetric modulated arc radiotherapy (VMAT) in oral cavity cancers in a resource constrained setting: experience and lessons learned. Br J Radiol 2015;88:20140795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanguineti G, Gunn GB, Endres EJ, Chaljub G, Cheruvu P, Parker B. Patterns of locoregional failure after exclusive IMRT for oropharyngeal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 72: 737–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sturges BK, Dickinson PJ, Bollen AW, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and histological classification of intracranial meningiomas in 112 dogs. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. Blackwell Publishing Inc; 2008. May;22:586–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ślosarek K, Osewski W, Grządziel A, et al. Integral dose: Comparison between four techniques for prostate radiotherapy. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2014. November 18;20:99–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang R, Xu S, Jiang W, Xie C, Wang J. Integral dose in three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy, intensity-modulated radiotherapy and helical tomotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2009. August 27;21:706–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoyama H, Westerly DC, Mackie TR, et al. Integral radiation dose to normal structures with conformal external beam radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006. February 7;64:962–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schroeck FR, Jacobs BL, Bhayani SB, Nguyen PL, Penson D, Hu J. Cost of New Technologies in Prostate Cancer Treatment: Systematic Review of Costs and Cost Effectiveness of Robotic-assisted Laparoscopic Prostatectomy, Intensity-modulated Radiotherapy, and Proton Beam Therapy. Eur Urol. 2017. March 31;72:712–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Théon AP, Feldman EC. Megavoltage irradiation of pituitary macrotumors in dogs with neurologic signs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1998. July 15;213:225–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohrer Bley C, Meier VS, Besserer J, Schneider U. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy dose prescription and reporting: Sum and substance of the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements Report 83 for veterinary medicine. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2019. February 20;31:12722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feuvret L, Noël G, Mazeron J-J, Bey P. Conformity index: a review. Radiation Oncology Biology. 2006. February 1;64:333–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaDue T, Klein MK. Toxicity criteria of the veterinary radiation therapy oncology group. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2001. October 27;42:475–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarz P, Meier V, Soukup A, et al. Comparative evaluation of a novel, moderately hypofractionated radiation protocol in 56 dogs with symptomatic intracranial neoplasia. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2018. October 11;32:2013–2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohrer Bley C, Meier V, Schwarz P, Roos M, Besserer J. A complication probability planning study to predict the safety of a new protocol for intracranial tumour radiotherapy in dogs. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. 2016. August 31:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Treggiari E, Maddox TW, Gonçalves R, Benoit J, Buchholz J, Blackwood L. Retrospective comparison of three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy vs prednisolone alone in 30 cases of canine infratentorial brain tumors. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound. 2016. November 15;:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee AW, Ng WT, Hung WM, et al. Evolution of treatment for nasopharyngeal cancer--success and setback in the intensity-modulated radiotherapy era. Radiother Oncol. 2014. March 11;110:377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fregnani ER, Parahyba CJ, Morais-Faria K, et al. IMRT delivers lower radiation doses to dental structures than 3DRT in head and neck cancer patients. Radiat Oncol. 2016. September 7;11:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kouloulias V, Thalassinou S, Platoni K, et al. The treatment outcome and radiation-induced toxicity for patients with head and neck carcinoma in the IMRT era: a systematic review with dosimetric and clinical parameters. Biomed Res Int. 2013. August; 2013:401261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Craft D, Khan F, Young M, Bortfeld T. The Price of Target Dose Uniformity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016. July 30;96:913–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benedict SH, Yenice KM, Followill D, Galvin JM. Stereotactic body radiation therapy: the report of AAPM Task Group 101. 2010; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffin LR, Nolan MW, Selmic LE, Randall E, Custis J, LaRue S. Stereotactic radiation therapy for treatment of canine intracranial meningiomas. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. 2014. December 18;14:e158–e170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelsey KL, Gieger TL, Nolan MW. Single fraction stereotactic radiation therapy (stereotactic radiosurgery) is a feasible method for treating intracranial meningiomas in dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2018. June 5;59:632–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariani CL, Schubert TA, House RA, et al. Frameless stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of primary intracranial tumours in dogs. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. 2013. September 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bentzen SM, Constine LS, Deasy JO, et al. Quantitative Analyses of Normal Tissue Effects in the Clinic (QUANTEC): An Introduction to the Scientific Issues. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. 2010;76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]