Abstract

Objective:

Loneliness is a prevalent and serious public health problem due to its effects on health, well-being, and longevity. Understanding correlates of loneliness is critical for guiding efforts toward the development of evidence-based strategies for prevention and intervention. Considering that patterns of association between age and loneliness vary, the present study sought to examine age-related differences in risk and protective factors for loneliness.

Methods:

We examined correlates of loneliness through a large web-based survey of 2,843 participants from across the US (20-69 years). Participants completed the 4-item UCLA Loneliness Scale, San Diego Wisdom Scale (measuring the components of wisdom: pro-social behaviors, emotional regulation, self-reflection, acceptance of divergent values, decisiveness, and social advising), and other psychosocial scales. Multivariate regression analyses were conducted to identify the best model of loneliness and examine potential age-related differences.

Results:

Age demonstrated a non-linear quadratic relationship with loneliness; levels were highest in the 20s and lowest in the 60s with another peak in the mid-40s. Across all decades, loneliness was associated with not having a spouse or partner, sleep disturbance, lower pro-social behaviors, and smaller social network. Lower social self-efficacy and higher anxiety were associated with worse loneliness in all age decades, except 60s. Loneliness was uniquely associated with decisiveness in the 50s, and with education and memory complaints in the 60s.

Conclusions:

Our findings identify several potentially modifiable targets related to loneliness, including several aspects of wisdom and social self-efficacy. Differential predictors at different decades suggest a need for a personalized/nuanced prioritizing of prevention/intervention targets.

Keywords: Wisdom, social network, social isolation, positive psychiatry, social media

INTRODUCTION

Loneliness is a major public health problem.1 In a meta-analysis,2 the all-cause mortality risk (odds ratio) of loneliness in the general population was 1.49. Loneliness has an adverse impact on physical, cognitive, and mental health.3 Efforts to prevent loneliness are critically important to advancement of public health. Evidence suggests that loneliness-focused interventions can be effective, particularly those focused on maladaptive social cognition rather than only improving social skills or networks.4,5 In a search for potentially modifiable targets, it is helpful to consider the characteristics that are strongly associated with loneliness. Several obvious candidates include social isolation and symptoms of depression and anxiety.6 These are commonly assessed in any mental health encounter, even initial primary care visits, and have been the key focus in loneliness interventions.4,7 However, such interventions, while partially effective, often do not fully address chronic and persistent loneliness. It is thus important to identify additional modifiable factors. Some of the particularly strong candidates include positive psychological traits such as resilience, optimism, and wisdom. Wisdom has a particularly strong negative association with loneliness (ρ=0.50-0.60). In a study of community dwelling adults, we found that lower overall wisdom, as measured with the San Diego Wisdom Scale (SD-WISE),8 was the strongest predictor of loneliness in a model that included living alone, mental well-being, age, sex, perceived stress, optimism, and subjective cognitive complaints.9 Wisdom is comprised of subcomponents that may be modifiable, but have not been widely examined, including social decision making, emotional regulation, pro-social behaviors, self-reflective behavior, acceptance of uncertainty and diversity of perspectives, and decisiveness.10 There have also been positive findings in regard to gender, education, and ethnicity, although the specific strength and pattern of relationships have varied among studies.9,11–14 Other correlates include inverse associations with social self-efficacy,15–17 and positive associations with chronic sleep disturbance,18–21 obesity,22,23 medication use,24,25 and cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease pathology.26–28 Findings in regard to social media use have been inconsistent.6,29,30

Prior research has been inconsistent in regard to the association between age and loneliness. Some studies show a linear decline, some an inverted U-pattern (peaking in middle age), and others a U-pattern (peaking in early and late adulthood).31 Our previous study found that loneliness was highest in the late 20s, mid-50s, and late 80s.9 To personalized care, it is important to consider the relative contribution of modifiable risk and protective factors in different stages of life. One prior US population-based study across the adult lifespan employed multiple regression analyses to examine the relative contribution of various loneliness-related factors.6 The strongest predictors were social variables, including difficulty approaching others, strong social support, meaningful daily interactions, and good social life/relationship. However, that study did not include measures of positive psychosocial factors or examine differential predictors among different age groups. To our knowledge, the present study is the first large-scale survey of loneliness to examine potential age-related differences in the association of loneliness with components of wisdom, as well as sociodemographic and other positive and negative psychological and health factors. We employed a step-wise multivariate approach to identify and prioritize the smallest and most effective combination of key modifiable targets. Our hypothesis was that multivariate predictors of loneliness would include higher levels of the components of wisdom, lower severity of depression and anxiety symptoms, smaller social network size, greater sleep disturbance, lower physical and mental well-being, as well as lower social self-efficacy, across the lifespan.

METHODS

Participants

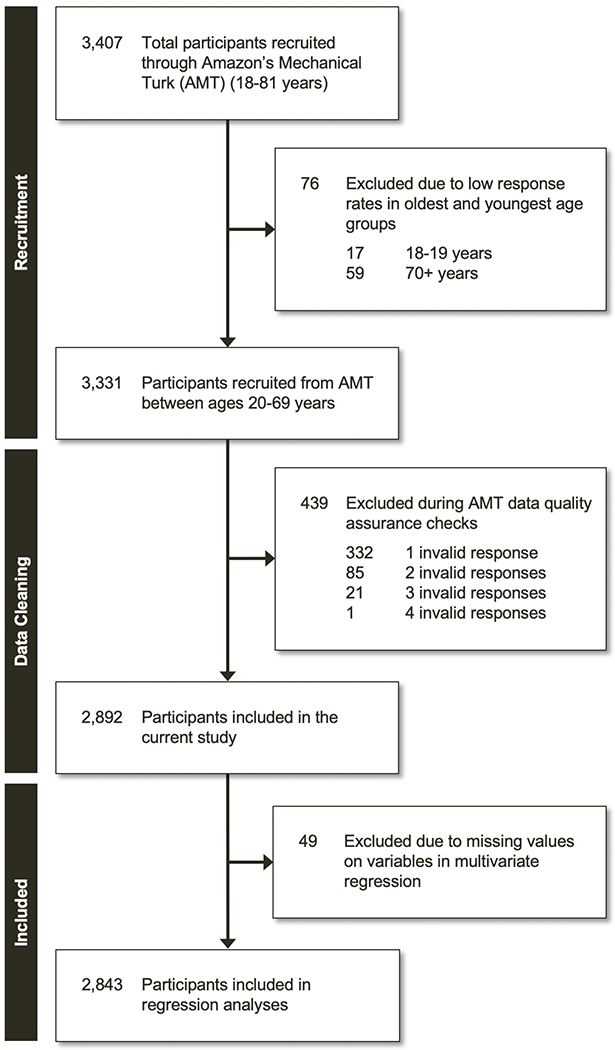

A total of 3,407 participants ages 18-81 years were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (AMT), an online crowdsourcing marketplace.32 Surveys from respondents ages <20 and ≥70 years were excluded due to low response rates. Inclusion criteria for analyses were: (1) age 20-69 years, (2) US resident, (3) MTurk Human Intelligence Task approval rating ≥90%,32 and (4) English fluency. To further ensure data validity, we applied a data cleaning procedure to eliminate participants who provided impossible or highly implausible responses to specific survey questions (Supplementary Appendix 1). These procedures yielded a final sample of N=2,892. For regression models, an additional 49 participants were excluded for missing values on any variable of interest (resulting N=2,843) (Figure 1). A waiver of documented informed consent was approved by the UC San Diego Human Research Protections Program.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram depicting the flow of participants in the study, from initial recruitment through Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) through final inclusion in regression models.

Measures

The survey included 90 items and required an average of 10.6 minutes to complete. Measured sociodemographic characteristics included age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, income, and living situation (number of people in household).

Loneliness was assessed using the 4-item version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (UCLA-4),33 which are a subset from the 20-item version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale.34 Wisdom was assessed using the 24-item SD-WISE,8 which includes six subscale scores: Pro-social behaviors, Emotional regulation, Self-reflection (Insight), Acceptance of divergent values, Decisiveness, and Social advising. Social network was measured with the sum of two items selected from the Berkman-Syme Social Network Index.35,36 Social self-efficacy was evaluated using four items from the Social Self-Efficacy Scale.37,38

Additional measured constructs included physical and mental well-being (12-item Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form,39,40 question on medication use), subjective cognitive decline (yes-no question), sleep disturbance (PROMIS Sleep Disturbance Short Form),41 depression (2-item Patient Health Questionnaire),42 anxiety (2-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale),43 happiness (Happiness Factor Score from the CES-D),44 resilience (2-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale),45 religiosity and spirituality (2-item Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality),46 and a question regarding average daily hours spent on social media for non-business reasons. See Supplementary Appendix 1 for additional description of measures.

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05 (two-tailed) for all analyses. Sociodemographic characteristics and all clinical outcome variables were summarized and compared across age decades using one-way ANOVA for continuous variables and Pearson Chi-square tests for discrete variables. We examined the relationship between loneliness and age by fitting a locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) curve. Then, we used spline models to model potential nonlinear relationship between these two variables. The LOESS curve suggests potential forms of non-linear relationships, and the spline functions allow for formal testing of suggested non-linear relationships.

We conducted linear multiple regression analyses with inference based on generalized estimating equations,47 using backward elimination to identify significant covariates of loneliness. Variables with variance inflation factor > 3 were considered high for potential multicollinearity and excluded from the model. Two models were performed. First, considering that the LOESS curve and quadratic spline function indicated a non-linear trend in the data, we modeled age as a continuous variable with a quadratic term (Model 1). We tested whether interaction terms were needed in the quadratic age model and found that adding interaction terms did not significantly improve the base model. This mean model was: Loneliness = Age + Age2 + Selected Variables. Second, because we were interested in the interaction between age decades and candidate factors, we also modeled age as a discrete variable with interaction terms between age decades and selected predictor variables (Model 2). We tested and confirmed that inclusion of interactions terms significantly improved the base model. This mean model was: Loneliness = Age Decade + Selected Variables + (Age Decade × Selected Variables). All analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Bonferroni procedure to control type I error at α=0.05.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics and age group differences on all measures of interest are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the sample was 42.9 (SD=12.7) years.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample (N = 2,892)

| Variable | 20-29 years (n = 525) |

30-39 years (n = 788) |

40-49 years (n = 604) |

50-59 years (n = 619) |

60-69 years (n = 356) |

F | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Variables | |||||||

| Age (years) | 25.8 (2.6) | 34.6 (2.8) | 44.7 (3.0) | 54.2 (2.8) | 63.8 (2.8) | -- | -- |

| Sex (Female) | 49.5% | 50.0% | 55.6% | 67.4% | 63.8% | 65.16 | <0.001 |

| Race | |||||||

| Caucasian | 59.6% | 70.3% | 77.2% | 81.1% | 89.0% | 154.02 | <0.001 |

| African American | 8.8% | 7.2% | 7.1% | 6.1% | 4.8% | ||

| Hispanic | 18.9% | 10.8% | 7.0% | 5.3% | 3.1% | ||

| Asian | 8.8% | 8.4% | 5.1% | 4.8% | 0.8% | ||

| Other | 4.0% | 3.3% | 3.6% | 2.6% | 2.2% | ||

| Education | 59.19 | <0.001 | |||||

| High School or Below | 43.9% | 34.4% | 42.2% | 48.9% | 47.6% | ||

| Bachelor’s Degree | 46.6% | 48.7% | 40.7% | 36.4% | 33.5% | ||

| Graduate Degree | 9.6% | 16.9% | 17.1% | 14.8% | 18.9% | ||

| Employment status | 361.70 | <0.001 | |||||

| Employed Full-time | 68.3% | 74.5% | 68.5% | 62.2% | 32.6% | ||

| Employed Part-time | 15.7% | 12.3% | 16.2% | 16.3% | 15.6% | ||

| Unemployed/Unable to work | 8.8% | 6.8% | 7.7% | 10.7% | 11.9% | ||

| Other | 7.1% | 6.4% | 7.5% | 10.8% | 39.9% | ||

| Marital status (married1) | 41.7% | 63.2% | 61.4% | 56.9% | 50.8% | 71.31 | <0.001 |

| Physical Health | |||||||

| BMI | 25.2 (6.2) | 27.2 (6.9) | 28.5 (7.4) | 28.3 (6.7) | 28.4 (6.4) | 22.87 | <0.001 |

| Medications (currently taking) | 28.4% | 27.4% | 36.6% | 46.2% | 56.5% | 128.03 | <0.001 |

| General health rating (MOS-12) | 73.3 (20.4) | 72.1 (19.9) | 69.0 (20.5) | 68.2 (21.2) | 70.4 (21.1) | 6.28 | <0.001 |

| Physical well-being (MOS-12) | 49.5 (9.2) | 50.3 (8.5) | 48.2 (9.8) | 45.6 (11.0) | 45.3 (11.0) | 30.13 | <0.001 |

| Mental and Cognitive Health | |||||||

| Mental well-being (MOS-12) | 42.1 (12.2) | 44 (12.1) | 45.4 (11.8) | 48.3 (10.6) | 50.6 (10.5) | 40.75 | <0.001 |

| Memory complaints (yes) | 28.8% | 21.1% | 28.1% | 30.5% | 23.0% | 21.56 | <0.001 |

| Sleep disturbance (PROMIS) | 51.6 (9.0) | 50.6 (8.9) | 51.2 (9.0) | 49.9 (9.4) | 47.3 (8.5) | 14.51 | <0.001 |

| Negative Psychological Features | |||||||

| Loneliness (UCLA-4) | 9.2 (2.5) | 8.8 (2.7) | 8.9 (2.6) | 8.5 (2.6) | 8.1 (2.6) | 11.52 | <0.001 |

| Depression (PHQ-2) | 2.1 (1.8) | 1.6 (1.7) | 1.5 (1.7) | 1.3 (1.6) | 1.0 (1.5) | 26.70 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety (GAD-2) | 2.2 (1.9) | 1.8 (1.9) | 1.8 (1.8) | 1.3 (1.7) | 1.0 (1.4) | 33.33 | <0.001 |

| Positive Psychological Features | |||||||

| SD-WISE Wisdom | |||||||

| Pro-social behaviors | 3.7 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.1 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.6) | 50.55 | <0.001 |

| Emotional regulation | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.8) | 12.01 | <0.001 |

| Self-reflection (Insight) | 3.9 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.7) | 4.0 (0.6) | 4.0 (0.6) | 1.28 | 0.276 |

| Acceptance of divergent values | 4.0 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.6) | 3.9 (0.7) | 3.9 (0.6) | 3.8 (0.6) | 3.18 | 0.013 |

| Decisiveness | 3.1 (0.9) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.7 (0.8) | 3.8 (0.8) | 38.92 | <0.001 |

| Social advising | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.7 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.6) | 0.90 | 0.464 |

| Total Score | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.4) | 18.74 | <0.001 |

| Social self-efficacy (SSES) | 13.3 (3.3) | 13.3 (3.4) | 13.3 (3.5) | 14.1 (3.2) | 14.3 (3.1) | 11.88 | <0.001 |

| Resilience (CD-RISC) | 5.2 (1.6) | 5.4 (1.8) | 5.5 (1.7) | 5.8 (1.6) | 6.0 (1.5) | 19.61 | <0.001 |

| Happiness (CESD) | 7.5 (3.4) | 8.0 (3.5) | 7.8 (3.5) | 8.5 (3.2) | 9.2 (3.1) | 16.81 | <0.001 |

| Religiosity/Spirituality (BMMRS) | 5.7 (1.9) | 5.7 (2.0) | 5.4 (1.9) | 5.0 (2.0) | 4.9 (1.9) | 20.26 | <0.001 |

| Social Interaction | |||||||

| Social network (SNI) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.7 (1.5) | 2.90 | 0.021 |

| Social media time | |||||||

| Less than 30 minutes | 10.5% | 20.9% | 25.2% | 29.9% | 32.9% | 215.74 | <0.001 |

| 30 minutes to 1 hour | 14.7% | 25.1% | 27.5% | 26.3% | 27.5% | ||

| 1 - 2 hours | 37.0% | 32.5% | 33.1% | 28.8% | 29.2% | ||

| 3+ hours | 37.9% | 21.4% | 14.2% | 15.0% | 10.4% |

Data are presented as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables or percent for categorical variables.

Or living in a marriage-like relationship

BMMRS = Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness-Spirituality; CD-RISC = Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; GAD-2 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; MOS-12 = Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form; PHQ-2 = Patient Health Questionnaire-2; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sleep Disturbance Short Form; SD-WISE = San Diego Wisdom Scale; SNI = Berkman-Syme Social Network Index; SSES = Social Self-Efficacy Scale; UCLA-4 = 4-item UCLA Loneliness Scale

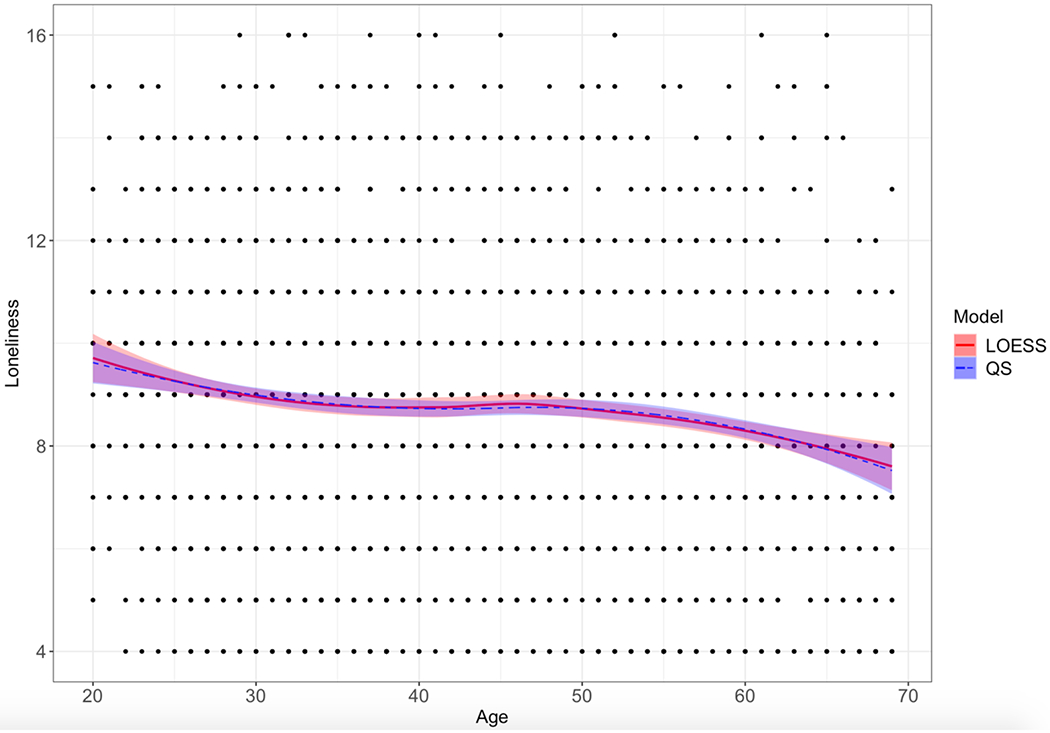

Loneliness severity across age

Across age decades, there was a significant difference in mean loneliness scores [F(4,2887)=11.5, p<0.001]. The relationship between loneliness and age was plotted and fitted with a LOESS curve to investigate potential non-linear relationships (Figure 2). The data suggested that loneliness was higher in the 20s than in the 60s, with another peak in the mid-40s. We modeled this non-linear relationship using a quadratic spline function with a single knot (break-point) at age 45. When tested against the null hypothesis of a linear relationship, the quadratic function was statistically significant (Wald statistic=5.50; p=0.019), indicating that there is one quadratic function between 20 and 44 years and another between 45 and 69 years.

Figure 2.

Non-linear Relationship between Loneliness and Age. Scatterplot of the relationship between loneliness and age (N = 2,843). The red line represents the locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) curve. The blue dashed line represents the quadratic spline (QS) function. Shaded areas around lines are the 95% confidence bands.

Multivariate models of loneliness

Model 1 accounted for 52.1% variance (Table 2). Results revealed that there was a significant quadratic effect of age on loneliness (Wald statistic=5.46; p=0.019), such that the non-linear curve showed a peak at 47.7 years. Greater loneliness was associated with not having a spouse or partner, greater sleep disturbance, lower pro-social behaviors, higher anxiety, lower self-efficacy, and smaller social network.

Table 2.

Multivariate regression model of loneliness with age modeled as a continuous variable and including an age quadratic term (Model 1: Loneliness = Age + Age2 + Selected Variables)

| Variable | Estimate | SE | Wald statistic | p-value | Partial η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.053 | 0.021 | 6.202 | 0.013* | 0.002 |

| Age2 | −0.001 | <0.001 | 5.475 | 0.019* | 0.002 |

| Sex | 0.161 | 0.073 | 4.879 | 0.027* | 0.002 |

| Race (African American vs. Caucasian) | 0.438 | 0.144 | 9.235 | 0.002* | 0.004 |

| Race (Hispanic vs. Caucasian) | −0.159 | 0.131 | 1.465 | 0.226 | 0.001 |

| Race (Asian vs. Caucasian) | −0.078 | 0.140 | 0.313 | 0.576 | <0.001 |

| Race (Other vs. Caucasian) | 0.148 | 0.215 | 0.475 | 0.491 | <0.001 |

| Education (Bachelor’s degree vs. high school or below) | 0.099 | 0.079 | 1.593 | 0.207 | 0.001 |

| Education (Graduate degree vs. high school or below) | 0.187 | 0.099 | 3.545 | 0.060 | 0.001 |

| Marital status | −0.858 | 0.071 | 144.672 | <0.001* | 0.049 |

| Medications | −0.104 | 0.079 | 1.735 | 0.188 | 0.001 |

| Memory complaints | 0.298 | 0.085 | 12.209 | <0.001* | 0.004 |

| Social Media Time (30-60 minutes vs. less than 30 minutes) | 0.009 | 0.104 | 0.007 | 0.932 | <0.001 |

| Social Media Time (1-2 hours vs. less than 30 minutes) | −0.205 | 0.096 | 4.606 | 0.032* | 0.002 |

| Social Media Time (3-4 hours vs. less than 30 minutes) | −0.016 | 0.114 | 0.021 | 0.886 | <0.001 |

| General health rating (MOS-12) | −0.011 | 0.004 | 6.677 | 0.010* | 0.003 |

| Sleep disturbance (PROMIS) | 0.038 | 0.005 | 62.454 | <0.001* | 0.025 |

| SD-WISE Decisiveness | −0.205 | 0.052 | 15.674 | <0.001* | 0.006 |

| SD-WISE Pro-social behaviors | −0.906 | 0.072 | 159.740 | <0.001* | 0.056 |

| SD-WISE Social advising | −0.238 | 0.072 | 10.860 | 0.001* | 0.004 |

| SD-WISE Acceptance of divergent values | 0.169 | 0.064 | 6.975 | 0.008* | 0.003 |

| Resilience (CD-RISC) | −0.052 | 0.030 | 3.075 | 0.080 | 0.001 |

| Anxiety (GAD-2) | 0.192 | 0.026 | 54.453 | <0.001* | 0.020 |

| Social self-efficacy (SSES) | −0.134 | 0.014 | 87.565 | <0.001* | 0.034 |

| Social network (SNI) | −0.414 | 0.027 | 233.424 | <0.001* | 0.085 |

p < 0.05

CD-RISC = Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; GAD-2 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; MOS-12 = Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Sleep Disturbance Short Form; SD-WISE = San Diego Wisdom Scale; SE = standard error; SNI = Berkman-Syme Social Network Index; SSES = Social Self-Efficacy Scale

Model 2 accounted for 52.3% variance (Supplementary Table 1). Results revealed significant main effects of marital status (p<0.001), sleep disturbance (p<0.02), pro-social behaviors (p<0.001), and social network (p<0.001). Across all age decades, greater loneliness was associated with not having a spouse or partner, greater sleep disturbance, lower pro-social behaviors, and smaller social network. Additionally, there were significant interactions between age decade and education, memory complaints, decisiveness, anxiety, and social self-efficacy. Having a Bachelor’s degree (p=0.046), compared to high school education, and endorsement of memory complaints (p=0.013) was associated with greater loneliness in the 60s, but not any other decade. Lower decisiveness was associated with greater loneliness in the 50s (p=0.012), but not any other decade. Higher anxiety (p<0.005) and lower social self-efficacy (p<0.001) were associated with greater loneliness in all age decades, except the 60s.

Considering the omnipresent relationships of pro-social behavior and social network with loneliness in the above models, we examined Pearson’s correlations and found that these bivariate correlations were significant in the total sample and each age group (Supplementary Table 2). Post-hoc Chi-square tests revealed that the strength of the relationship was significantly stronger from the 20s to the 60s (χ2=34.7, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

As hypothesized, loneliness was associated with smaller social network, fewer pro-social behaviors, lack of a spouse or partner, lower social self-efficacy, and higher sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms. Depression did not emerge as a key predictor, contrary to our hypothesis. The relationship between loneliness and depression was accounted for by the variance associated with anxiety, which is consistent with studies showing that social anxiety is the strongest predictor of greater loneliness.6,48 Examining trends of loneliness across age, we found that loneliness was highest in the 20s and lowest in the 60s with another peak in mid-40s. This finding replicates our previous study showing that loneliness peaks in early adulthood and middle-age,9 and supports the “paradox of aging” that psychological well-being improves after middle age despite declining physical and cognitive functioning.49 Social network, marital status, pro-social behaviors, and sleep were consistent predictors of loneliness across all decades, which is consistent with prior research.50–52 Although the association of general self-efficacy and loneliness has been previously examined, to our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to examine social self-efficacy across the adult lifespan. This investigation is also one of the few to study the relative contributions of loneliness-related factors in multiple regression analyses in a large population-based survey,6 and the first to examine the association with components of wisdom.

Loneliness was associated with both external (e.g., marital status, social network) and internal (e.g., pro-social behaviors, self-efficacy) factors. Strategies to reduce loneliness have primarily focused on decreasing objective social isolation and improving social skills.1,5 However, social network size does not necessarily translate to high quality relationships.5 Loneliness can still occur if people are unable to emotionally connect with and share in the experiences of their network.48,50 Socially/interpersonally rewarding experiences are more likely to reduce loneliness than general social-group activities.53 Interventions are likely to be more effective if they also incorporate internal factors, such as mastery of social skills and reducing maladaptive social cognitions. Our findings in regard to pro-social behaviors and social self-efficacy indicate other points of intervention. Wisdom may moderate the relationship between social network and loneliness through one’s ability to demonstrate pro-social behaviors, such as compassion and social cooperation, and to accurately perceive and interpret others’ emotions (“theory of mind”). Indeed, pro-social behaviors and social network are positively correlated; the strength of this relationship was stronger with increasing age, concomitant with decreasing levels of loneliness, suggesting that compassion is necessary to have a social network. Pro-social behaviors facilitate social cooperation, decreasing competition and contentious behavior. Individuals with pro-social motives are more likely to achieve better joint outcomes, which can increase social connectedness. In a recent study examining qualitative aspects of older adults’ experience of loneliness,54 we found that compassion is an important subtheme for coping with loneliness. This finding is also consistent with reports of the protective influence of volunteer work.55 One key to prevent or reduce loneliness may be to encourage individuals to engage in volunteer work to help others.

Higher self-efficacy increases the likelihood of sustained efforts toward social connection. According to the classic perceived self-efficacy theory posited by Bandura,56 the key to behavior change is through improved self-efficacy beliefs. Self-efficacy can be improved through guided mastery experiences, and is particularly effective if the targeted behavior is modeled by a person whom the individual perceives as resembling themselves on relevant dimensions, which suggests the potential for peer-based facilitators in social self-efficacy interventions. Increasing beliefs of social self-efficacy and pro-social behaviors may improve quality of communication and connection with one’s existing social environment and make one more apt to benefit from strategies to improve social network and reduce isolation. Notably, wisdom as well as pro-social behaviors can be potentially enhanced with psychosocial interventions.57,58

The association between impaired sleep and loneliness appears to be complex and bidirectional. Some studies have hypothesized that stress and hypervigilance to social threats associated with loneliness may impact sleep quality.59 These relationships appear to be independent of depression,60 though depression itself affects sleep. One study found that anxiety and rumination fully mediate relationship between loneliness and sleep quality,61 whereas another reported that the sleep-loneliness relationship persists even after controlling for depression, anxiety, and perceived stress.52 Sleep may also mediate the relationship of loneliness and other health outcomes.62 Sleep deprivation itself can lead to a behavioral profile of social withdrawal and loneliness, along with decreased fMRI brain activity in the theory of mind network (associated with understanding the intentions of others) and increased activity in a network associated with interpersonal space intrusion and that warn of human approach.63

There were some notable differences in predictors of loneliness across decades. Decisiveness was predictive of loneliness in the 50s. This component allows for integration of cognitive processes that are crucial to wisdom,64 a skill that may be important in building and maintaining one’s social relationships. Midlife may be a time period in which individuals have sufficiently developed this trait but also when other physical/cognitive risk factors may be less salient, making it a more relevant factor contributing to loneliness. Memory complaints were associated with greater loneliness in the 60s. Declining cognitive function may contribute to limited mobility and barriers to using technology to communicate with friends and family. Interestingly, physical health and well-being in addition to anxiety and social self-efficacy (which were associated with loneliness every other decade) were not predictors of loneliness in older adults, indicating that cognitive barriers may be more relevant than physical or psychological ones to feeling socially connected. It further suggests the importance of “mind over matter” – i.e., one may overcome physical barriers to connectedness (e.g., access to other people) if one has social and emotional skills/qualities (e.g., social self-efficacy, wisdom).

Limitations and Strengths

Our study has several limitations. We used the 4-item UCLA Loneliness Scale to minimize the length/burden of the overall survey. Using data from an independent study of community dwelling adults,49,65 the 4-item version was strongly correlated with the full scale (ρ=0.90). AMT offers many advantages to conduct clinical and behavioral research, but potentially reduces quality of the data collected in unsupervised conditions. Consistent with standard scholarly research using AMT,32 we applied data quality checks to ensure reliability and validity of results. Due to the large sample size, many variables were statistically significant but the effect sizes of some covariates were small.66,67 To increase clinical significance, variables with very small effect sizes were not interpreted (even if they reached statistical significance). Nevertheless, although each predictor may only account for a small amount of variability, together, they help explain a large percentage of variance in loneliness (R2 of multivariate models were large, accounting for 52% variance).

The study included a broad assessment of physical and mental/psychological traits. All data were based on self-report, which may be subject to recall and response biases. On the other hand, the anonymized nature of the online survey may contribute to respondents feeling more comfortable to disclose negative traits and symptoms. This study did not include older adults in their 70s or 80s. Considering previous research suggesting that loneliness increases again in older age9 and the number of risk factors predisposing older adults to loneliness (e.g., smaller social network, widowhood, declines in physical health, and increased prevalence of dementia), findings from this study may not be generalizable to the oldest segment of the population. Finally, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to make causal inferences. Future comprehensive longitudinal studies of loneliness, including real-time measurement of fluctuations in loneliness using ecological momentary assessment, are needed to better understand mechanisms of risk and protective factors of loneliness to better guide prevention and intervention efforts.

Despite the above described limitations, the present study has several strengths including a large sample of over 2,800 adults across five decades, with diversity in gender, race/ethnicity, income, and geographic region within the US. This is the largest known study of wisdom in a national sample and one of the few to examine the relationship between wisdom and loneliness. Additionally, we examined how specific components of wisdom relate to loneliness and elucidated behavioral targets that may be appropriate for intervention.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Our findings suggest that the pro-social behaviors and decisiveness components of wisdom may be unique aspects of preventing or reducing chronic loneliness. Intervention and prevention efforts studies should incorporate social network, pro-social behavior, and social self-efficacy modifications.58,68 These efforts should also consider stage-of-life issues in terms of the cause and experience of loneliness within the broader context of the individual’s phase of life and milestones.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL POINTS.

The epidemic of loneliness contributes to the markedly increasing rates of “deaths of despair” due to suicides and opioid abuse.

Reducing loneliness is a public health priority, but current interventions focused solely on decreasing social isolation have only been modestly effective.

Interventions targeting wisdom, specifically compassion or pro-social behaviors, may be a helpful addition to the armamentarium of efforts to prevent and reduce chronic loneliness and its downstream effects on health outcomes and well-being.

PODCAST SUMMARY.

Loneliness is a is a major public health problem. It is a risk factor for not only adverse mental health but also physical health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and premature mortality. Its health impact is comparable to that of cigarette smoking and obesity. There has been a growing concern about loneliness across all ages; however, we also know that severity of loneliness differs across the lifespan. This paper examined risk and protective factors for loneliness and how they vary by age decades. A specific positive psychological trait that we were interested in was wisdom. Wisdom is a holistic, multidimensional human trait comprised of specific components: pro-social behaviors, emotional regulation, self-reflection, acceptance of divergent values, decisiveness, and social advising. Our results revealed that loneliness levels were highest in the 20s and lowest in the 60s, with another peak in the mid-40s, which is consistent with prior studies. Across all age decades, greater loneliness was associated with not having a spouse or partner, sleep disturbance, lower pro-social behaviors, and smaller social network. There were some differences in the contributors to loneliness across age decades. Loneliness was uniquely associated with decisiveness in the 50s and memory complaints in the 60s. Additionally, social self-efficacy and symptoms of anxiety were not associated with loneliness in the 60s, as they were in all other decades. Our findings suggest that wisdom may be a unique aspect of addressing chronic loneliness. Differential predictors at different decades suggest a need for a personalized/nuanced prioritizing of prevention/intervention targets.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Kasey Yu (from University of California San Diego) for her contributions in preparing tables and formatting the manuscript. Ms. Yu has no conflicts of interest to declare.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This study was supported, in part, by the UC San Diego Center for Healthy Aging, NIH grants K23 MH118435 (PI: Tanya T. Nguyen), K23 MH119375 (PI: Ellen E. Lee), T32 MH019934 (PI: Dilip V. Jeste), R01 MH094151 (PI: Dilip V. Jeste), and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

ROLE OF THE SPONSOR

The sponsors had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or publication of this study.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness:Clinical Import and Interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10(2):238–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10(2):227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mushtaq R, Shoib S, Shah T, Mushtaq S. Relationship between loneliness, psychiatric disorders and physical health ? A review on the psychological aspects of loneliness. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2014;8(9):We01–04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen-Mansfield J, Perach R. Interventions for alleviating loneliness among older persons: a critical review. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(3):e109–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masi CM, Chen H-Y, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(3):219–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DesHarnais Bruce L, Wu JS, Lustig SL, Russell DW, Nemecek DA. Loneliness in the United States: A 2018 National Panel Survey of Demographic, Structural, Cognitive, and Behavioral Characteristics. Am J Health Promot. 2019:890117119856551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health & social care in the community. 2018;26(2):147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas ML, Bangen KJ, Palmer BW, et al. A new scale for assessing wisdom based on common domains and a neurobiological model: The San Diego Wisdom Scale (SD-WISE). J Psychiatr Res. 2019;108:40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee EE, Depp C, Palmer BW, et al. High prevalence and adverse health effects of loneliness in community-dwelling adults across the lifespan: role of wisdom as a protective factor. International psychogeriatrics. 2019;31(10):1447–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeste DV, Lee EE. The Emerging Empirical Science of Wisdom: Definition, Measurement, Neurobiology, Longevity, and Interventions. Harvard review of psychiatry. 2019;27(3):127–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djukanovic I, Sorjonen K, Peterson U. Association between depressive symptoms and age, sex, loneliness and treatment among older people in Sweden. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19(6):560–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkley LC, Wroblewski K, Kaiser T, Luhmann M, Schumm LP. Are U.S. older adults getting lonelier? Age, period, and cohort differences. Psychol Aging. 2019;34(8):1144–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laurson KR, McCann DA, Senchina DS. Age, sex, and ethnicity may modify the influence of obesity on inflammation. Journal of investigative medicine : the official publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research. 2011;59(1):27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jakobsson U, Hallberg IR. Loneliness, fear, and quality of life among elderly in Sweden: a gender perspective. Aging clinical and experimental research. 2005;17(6):494–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai W, Wang KT, Wei M. Reciprocal relations between social self-efficacy and loneliness among Chinese international students. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2017;8(2):94–102. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei M, Russell DW, Zakalik RA. Adult Attachment, Social Self-Efficacy, Self-Disclosure, Loneliness, and Subsequent Depression for Freshman College Students: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52(4):602–614. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C-J, Lin P-C, Hsiu H-L. The relationships among adult attachment, social self-efficacy, distress self-disclosure, loneliness and depression of college students with romance. [The relationships among adult attachment, social self-efficacy, distress self-disclosure, loneliness and depression of college students with romance.]. Bulletin of Educational Psychology. 2011;43(1):155–174. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyall LM, Wyse CA, Graham N, et al. Association of disrupted circadian rhythmicity with mood disorders, subjective wellbeing, and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study of 91 105 participants from the UK Biobank. The lancet Psychiatry. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Berntson GG, et al. Do lonely days invade the nights? Potential social modulation of sleep efficiency. Psychol Sci. 2002;13(4):384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhatti AB, Haq AU. The Pathophysiology of Perceived Social Isolation: Effects on Health and Mortality. Cureus. 2017;9(1):e994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkley LC, Preacher KJ, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness impairs daytime functioning but not sleep duration. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2010;29(2):124–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schumaker JF, Krejci RC, Small L, Sargent RG. Experience of Loneliness by Obese Individuals. Psychological Reports. 1985;57(3_suppl):1147–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarlio-Lähteenkorva S, Lahelma E. The association of body mass index with social and economic disadvantage in women and men. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;28(3):445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boehlen F, Herzog W, Quinzler R, et al. Loneliness in the elderly is associated with the use of psychotropic drugs. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2015;30(9):957–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Theeke LA, Mallow J. Loneliness and quality of life in chronically Ill rural older adults: Findings from a pilot study. The American journal of nursing. 2013;113(9):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boss L, Kang D-H, Branson S. Loneliness and cognitive function in the older adult: a systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2015;27(4):541–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donovan NJ, Wu Q, Rentz DM, Sperling RA, Marshall GA, Glymour MM. Loneliness, depression and cognitive function in older U.S. adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2017;32(5):564–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donovan NJ, Okereke OI, Vannini P, et al. Association of Higher Cortical Amyloid Burden With Loneliness in Cognitively Normal Older Adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(12):1230–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berezan O, Krishen AS, Agarwal S, Kachroo P. Exploring loneliness and social networking: Recipes for hedonic well-being on Facebook. Journal of Business Research. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reer F, Tang WY, Quandt T. Psychosocial well-being and social media engagement: The mediating roles of social comparison orientation and fear of missing out. New Media & Society. 2019;21(7):1486–1505. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Victor CR, Yang K. The prevalence of loneliness among adults: a case study of the United Kingdom. The Journal of psychology. 2012;146(1-2):85–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mason W, Suri S. Conducting behavioral research on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Behavior research methods. 2012;44(1):1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. A Brief Measure of Loneliness Suitable for Use with Adolescents. Psychological Reports. 1993;72(3_suppl):1379–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loucks EB, Sullivan LM, D’Agostino RB Sr, Larson MG, Berkman LF, Benjamin EJ. Social networks and inflammatory markers in the Framingham Heart Study. Journal of biosocial science. 2006;38(6):835–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109(2):186–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zullig KJ, Teoli DA, Valois RF. Evaluating a brief measure of social self-efficacy among U.S. adolescents. Psychol Rep. 2011;109(3):907–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muris P Relationships between self-efficacy and symptoms of anxiety disorders and depression in a normal adolescent sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32(2):337–348. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller S. SF-12: how to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. Boston: QualityMetric Inc. & the Health Assessment Lab. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical care. 1996:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. Initial adult health item banks and first wave testing of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS™) network: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63(11):1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical care. 2003:1284–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;146(5):317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vaishnavi S, Connor K, Davidson JR. An abbreviated version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), the CD-RISC2: Psychometric properties and applications in psychopharmacological trials. Psychiatry research. 2007;152(2-3):293–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masters KS. Brief multidimensional measure of religiousness/spirituality (BMMRS). Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. 2013:267–269. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tang W, He H, Tu X. Applied categorical and count data analysis. Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40(2):218–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas ML, Kaufmann CN, Palmer BW, et al. Paradoxical trend for improvement in mental health with aging: a community-based study of 1,546 adults aged 21–100 years. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2016;77(8):e1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Measuring social isolation among older adults using multiple indicators from the NSHAP study. The journals of gerontology Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2009;64 Suppl 1:i38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suanet B, van Tilburg TG. Loneliness declines across birth cohorts: The impact of mastery and self-efficacy. Psychology and Aging. 2019;34(8):1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kurina LM, Knutson KL, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT, Lauderdale DS, Ober C. Loneliness Is Associated with Sleep Fragmentation in a Communal Society. Sleep. 2011;34(11):1519–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Solomonov N, Bress JN, Sirey JA, et al. Engagement in Socially and Interpersonally Rewarding Activities as a Predictor of Outcome in “Engage” Behavioral Activation Therapy for Late-Life Depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2019;27(6):571–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morlett Paredes A, Lee EE, Chik L, et al. Qualitative study of loneliness in a senior housing community: the importance of wisdom and other coping strategies. Aging & Mental Health. 2020:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carr DC, Kail BL, Matz-Costa C, Shavit YZ. Does becoming a volunteer attenuate loneliness among recently widowed older adults? The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2018;73(3):501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bandura A Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Treichler EBH, Glorioso D, Lee EE, et al. A pragmatic trial of a group intervention in senior housing communities to increase resilience. International Psychogeriatrics. 2020;32(2):173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee E, Bangen K, Avanzino J, et al. Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials to Enhance Components of Wisdom: Pro-social Behaviors, Emotional Regulation, and Spirituality. JAMA Psychiatry. in press, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aanes MM, Hetland J, Pallesen S, Mittelmark MB. Does loneliness mediate the stress-sleep quality relation? The Hordaland Health Study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(6):994–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Crawford LE, et al. Loneliness and health: potential mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(3):407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zawadzki MJ, Graham JE, Gerin W. Rumination and anxiety mediate the effect of loneliness on depressed mood and sleep quality in college students. Health Psychology. 2013;32(2):212–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Christiansen J, Larsen FB, Lasgaard M. Do stress, health behavior, and sleep mediate the association between loneliness and adverse health conditions among older people? Soc Sci Med. 2016;152:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ben Simon E, Walker MP. Sleep loss causes social withdrawal and loneliness. Nature Communications. 2018;9(1):3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Meeks TW, Jeste DV. Neurobiology of wisdom: a literature overview. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(4):355–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aftab A, Lee EE, Klaus F, et al. Meaning in Life and Its Relationship With Physical, Mental, and Cognitive Functioning: A Study of 1,042 Community-Dwelling Adults Across the Lifespan. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2019;81(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sullivan Gail M., Feinn Richard. Using Effect Size—or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2012;4(3):279–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cohen J Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jeste DV, Lee EE, Cacioppo S. Battling the Modern Behavioral Epidemic of Loneliness: Suggestions for Research and Interventions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.