Abstract

Background

COVID-19 may induce a coagulation dysregulation resulting in a prothrombotic state with a higher risk of arterial and venous thrombosis. This abnormal thrombotic diathesis can lead to pulmonary embolism, stroke, and intracardiac thrombosis.

Case summary

We present two cases of unusual intracardiac thrombosis in patients hospitalized for COVID-19. In both cases, imaging tests (such as transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), computed tomography scan of the chest, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging) showed evidence of unusual intracardiac thrombosis with thrombi adherent to regularly contracting walls.

Discussion

This evidence confirms that COVID-19 induces a hypercoagulable state which can result in intracardiac thrombosis. Therefore, TTE is indicated in all COVID-19 patients for early diagnosis, and prompt anticoagulant therapy is to be considered as a thromboprophylaxis strategy.

Keywords: Thrombus, Coagulation, Anticoagulant, Transthoracic echocardiography, Case series

Learning points

COVID-19 induces a prothrombotic state resulting in unusual intracardiac thrombosis. Intracardiac thrombi can form even on regularly contracting walls.

Anticoagulant therapy with Heparin is to be considered for COVID-19 patients. Long-term anticoagulant therapy with Warfarin is indicated in case of recent intracardiac thrombosis, in order to prevent recurrences.

Introduction

COVID-19 is a disease caused by a new strain of virus called SARS-CoV-2; it first spread in China and later rapidly across many other countries, including Italy in February 2020.

Most of the patients experience fever, cough, dyspnoea, and upper respiratory tract symptoms, with some cases progressing to pneumonia, multi-organ failure, and death.1,2 Growing evidence shows an excessive coagulation activation in COVID-19 patients, resulting in arterial and venous thrombosis, and therefore leading to a poor prognosis.3,4

Herein, we discuss two cases of unusual intracardiac thrombosis in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

Timeline

| Patient 1 | |

| Day 1 |

Admission to Emergency Department. Initial blood tests, 12-lead electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, nasopharyngeal swab (positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) with evidence of intracardiac thrombosis. Start of specific COVID-19 therapy (hydroxychloroquine, antibiotics) and anticoagulant therapy (Enoxaparin). |

| Day 3 | Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging confirmed intracardiac thrombosis. |

| Day 4 | Coronary angiography: moderate coronarosclerosis, no critical stenoses. |

| Day 13 | Second TTE showed the dissolution of the thrombus. |

| Day 15 | Enoxaparin was switched to oral anticoagulant (Warfarin) for long-term treatment. |

| Day 18 | A second nasopharyngeal swab tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. |

| Day 20 | The patient was discharged asymptomatic. |

| Follow-up | The patient was asymptomatic at a 2-months follow-up visit. Transthoracic echocardiography showed normal left ventricular systolic function (LVEF 61%) without evidence of intracardiac thrombosis. |

| Patient 2 | |

| Day 1 |

Admission to Emergency Department. Initial blood tests, 12-lead electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, first CT scan of the chest (showing no evidence of intracardiac thrombosis), nasopharyngeal swab (positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA). Start of specific COVID-19 therapy (antiviral drugs, hydroxychloroquine, antibiotics). |

| Day 4 |

Ischaemic stroke. Transthoracic echocardiography showed intracardiac thrombosis. Second CT scan of the chest confirmed the presence of the thrombus. |

| Day 6 | Start of anticoagulant therapy (Enoxaparin). |

| Day 18 | Second TTE and third CT scan of the chest showed no evidence of intracardiac thrombosis. |

| Day 19 | Enoxaparin was switched to oral anticoagulant (Warfarin) for long-term treatment. |

| Day 20 | A second nasopharyngeal swab tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. |

| Day 21 | The patient was discharged asymptomatic. |

| Follow-up | Transthoracic echocardiography performed 3 months after discharge confirmed the severe systolic dysfunction (LVEF 31%), but without evidence of intracardiac thrombosis. The patient was mildly symptomatic for dyspnoea due to the pre-existing heart failure. |

Report of two cases

Patient 1

A 74-year-old hypertensive male without a previous history of cardiovascular events was admitted to the Emergency Department with fever, dyspnoea, and cough for a few days. Current medical therapy upon admission consisted only of Ramipril 5 mg once daily.

Physical examinations on admission showed blood pressure of 140/110 mmHg, heart rate of 100 beats per minute, oxygen saturation of 98% while in oxygen therapy (15 L/min with non-rebreather mask), and body temperature of 37.6°C; heart sounds were tachycardic and rhythmic without pathologic heart murmurs, fine rales were evident at lung auscultation, no peripheral oedema was present. Blood tests revealed increased levels of white blood cell count, D-dimer, ferritin, C-reactive protein, and lactate dehydrogenase; most of these parameters remained consistently high during hospitalization, while only white blood cell count normalized after approximately 2 weeks from admission (Table 1). A 12-lead electrocardiogram was also recorded, showing sinus rhythm without any particular alterations. Findings on chest X-ray were typical for viral pneumonia, i.e., bilateral thickening and interstitial infiltrates. Lastly, the patient tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA, using real-time RT-PCR on samples from a nasopharyngeal swab.

Table 1.

Laboratory results for patient 1

| Blood test | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 10 | Day 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Haemoglobin (g/dL) (normal values: 14.0–18.0 g/dL) |

12.9b | 13.7b | 13.1b | 12.8b | 12.5b | 11.1b | 10.2b |

|

White blood cell count (×103/μL) (normal values: 4.0–10.8 ×103/μL) |

12.9a | 14.7a | 16.9a | 12.7a | 13.2a | 12.5a | 8.8 |

|

Neutrophil count (abs.), ×103/μL (normal values: 1.5–8.0 ×103/μL) |

10.9a | 11.8a | NA | 10.4a | 11.1a | 9.6a | 7.2 |

|

Lymphocyte count (abs.), (×103/μL) (normal values: 0.9–4.0 ×103/μL) |

0.9 | 1.8 | NA | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 1.1 |

|

Platelet count (×103/μL) (normal values: 130–400 ×103/μL) |

480a | 321 | 271 | 254 | 221 | 182 | 205 |

|

Creatinine (mg/dL) (normal values: 0.7–1.2 mg/dL) |

1.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

|

Prothrombin time (s) (normal values: 11.0–12.5 s) |

14.5a | NA | NA | 12.6a | NA | 11.3 | 12.5 |

|

International normalized ratio (INR) (target range for the patient: 1) |

1.1 | NA | NA | 1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1 |

|

Activated partial thromboplastin time (s) (normal values: 30–40 s) |

20.2b | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

|

Fibrinogen (mg/dL) (normal values: 170–410 mg/dL) |

282 | NA | 162b | NA | 134b | 434a | 1210a |

|

D-dimer (ng/mL) (normal values: <232 ng/mL) |

2931a | 2883 | NA | 3044a | 2810a | 606a | 412a |

|

C-reactive protein (mg/L) (normal values: <5.0 mg/L) |

14.2a | 9.4a | 5.6a | 3.3 | 2.1 | 31.1a | 110.5a |

|

Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) (normal values: 135–225 U/L) |

295a | 331a | NA | 327a | NA | 346a | 273a |

|

Ferritin (ng/mL) (normal values: 30–400 ng/mL) |

1580a | 1730a | NA | 1196 | 1129a | 1090a | 1415a |

|

Procalcitoninc (ng/mL) (normal values: <0.5 ng/mL) |

NA | <0.1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

The value is greater than normal.

The value is less than normal.

Procalcitonin levels measured with chemiluminescence immunoassay.

In order to identify the patient’s main comorbidities and to best organize the hospitalization in one of the ‘COVID-19 units’ within the hospital, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is routinely performed in all COVID-19 patients admitted to the ER in our Institution. In this patient, the TTE revealed a dilated left ventricle with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVEF 30%) and generalized hypokinesia especially regarding the apical segments. Two large thrombi were also visible in the apex of the left ventricle, both ∼25–30 mm long: the anterior one, fixed to the anterior apical wall, was oval in shape with a large base (Figure 1, left;Supplementary material online,Videos S1 andS2); the postero-inferior one, adherent to the inferior wall, was elongated, pedunculated and mobile (Figure 1, right). Position and shape of both thrombi were unusual, especially in regard to the posterior one which was adherent to a regularly contracting wall.

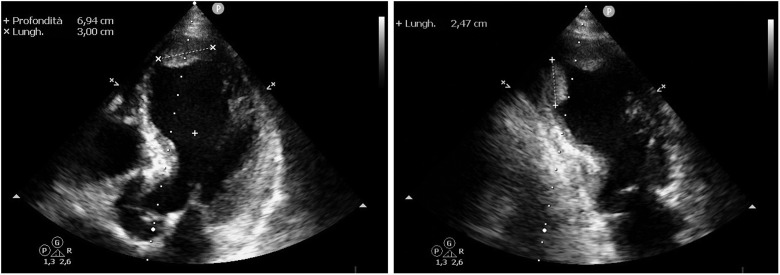

Figure 1.

Patient no. 1: Transthoracic echocardiogram shows intracardiac thrombi.Left image: The thrombus in the apex of the left ventricle is adherent to anterior apical wall and it is 30.0 mm long in its larger diameter. Right image: The second thrombotic formation, adherent to the inferior wall, is elongated, pedunculated, and mobile, with a larger diameter of 24.7 mm.

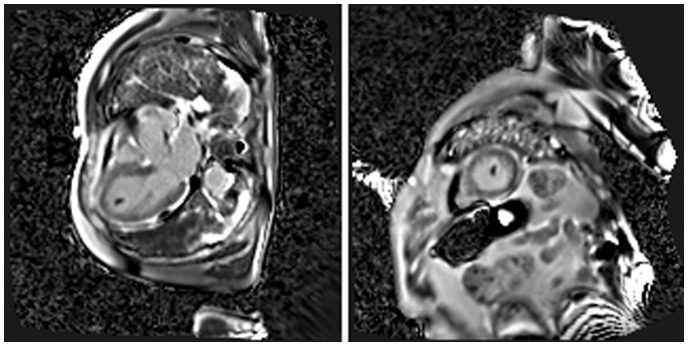

As a further study, the patient underwent a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the heart, which confirmed the left ventricular dilation (ESV 107 mL, 59 mL/m2) and the severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVEF 22%) with the already known regional wall hypocontractility, and more accurately described morphology and position of the thrombi (Figure 2;SupplementaryVideos S3 andS4]. Additionally, no late gadolinium enhancement was observed.

Figure 2.

Patient no. 1: magnetic resonance imaging scan (three-chamber view and short-axis view). Phase sensitive inversion recovery (PSIR) sequences in three-chamber view (left) and short-axis view (right) show an intracavitary hypointense formation, relatable to thrombus, at the apex of left ventricle.

In order to explain the reduced LVEF, a coronary angiography was also performed, revealing a diffuse moderate coronarosclerosis without critical stenoses of coronary arteries.

Alongside the treatment for COVID-19 pneumonia (hydroxychloroquine and antibiotics)1 and for acute heart failure (inotropic agents, including Dobutamine, for low cardiac output), anticoagulant therapy was also administered (Enoxaparin sodium 100 IU per kg, twice a day).

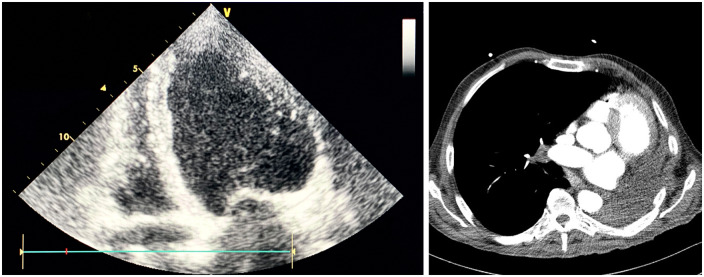

After 13 days of anticoagulant therapy, a second TTE was performed, with no evidence of intracardiac thrombosis (Figure 3;Supplementary material online,Video S4). Furthermore, the test showed a marked improvement in systolic function (LVEF 57%), likely as a result of the inotropic medical therapy with Dobutamine and the absence of acute ischaemic heart disease in the first place. The parenteral anticoagulant therapy was then gradually switched to a long-term oral anticoagulant therapy with Warfarin (INR range of 2.0–3.0) starting on the 15th day of hospitalization, in order to prevent recurrent thrombosis.

Figure 3.

Patient no. 1: Transthoracic echocardiogram after anticoagulant therapy. No visible thrombi in the left ventricle after 13 days of anticoagulant therapy.

The patient’s clinical conditions rapidly improved in the following days, without evidence of dyspnoea, cough, or fever; in addition, chest X-ray showed less compact interstitial infiltrates. The patient also tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 RNA on a second nasopharyngeal swab, and thus was discharged asymptomatic after 20 days of hospitalization. Medical therapy at discharge consisted of Warfarin once daily (dose adjustment based on INR) and Ramipril 5 mg once daily.

The patient was asymptomatic at a 2-months follow-up visit; the TTE showed normal left ventricular systolic function (LVEF 61%) without evidence of intracardiac thrombosis.

Patient 2

A 70-year-old male was hospitalized for worsening fatigue, dyspnoea, cough, and fever. He was suffering from post-ischaemic heart failure (LVEF 33% in January 2020) after a previous myocardial infarction back in 2000 (with evidence of diffuse myocardial hypocontractility at follow-up echocardiography); moreover, following the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma of the lung, a left total pneumonectomy was performed on September 2019 (no disease activity was found at subsequent follow-up checks). The patient was in treatment with Ramipril 5 mg once daily, Bisoprolol 1.25 mg once daily, and Rosuvastatin 10 mg once daily.

Initial physical examinations revealed a blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg, heart rate of 105 beats per minute, oxygen saturation of 94% while in oxygen therapy (5 L/min), and body temperature of 37.8°C; heart sounds were tachycardic and rhythmic without pathologic heart murmurs, crackles, and rales were evident at lung auscultation in the right lower lobe, mild peripheral oedema was present. Blood test results (Table 2), electrocardiogram, and radiological findings [chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest] were similar compared to the previous patient; the diagnosis of COVID-19 was completed by the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA on nasopharyngeal swab samples (using real-time RT-PCR).

Table 2.

Laboratory results for patient 2

| Blood test | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 10 | Day 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Haemoglobin (g/dL) (normal values: 14.0–18.0 g/dL) |

12.8b | 13.2b | 11.2b | 11.7b | 12.1b | 11.0b | 11.9b |

|

White blood cell count, ×103/μL (normal values: 4.0–10.8 ×103/μL) |

13.0a | 12.8a | 13.8a | 13.6a | 13.5a | 18.8a | 20.0a |

|

Neutrophil count (abs.), ×103/μL (normal values: 1.5–8.0 ×103/μL) |

10.7a | 10.3a | 11.6a | 11.5a | 11.6a | 16.7a | 17.6a |

|

Lymphocyte count (abs.), ×103/μL (normal values: 0.9–4.0 ×103/μL) |

1.6 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

|

Platelet count, ×103/μL (normal values: 130–400 ×103/μL) |

366 | 344 | 269 | 257 | 226 | 286 | 309 |

|

Creatinine (mg/dL) (normal values: 0.7–1.2 mg/dL) |

1.3a | 1.4a | 1.4a | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.8 |

|

Prothrombin time (s) (normal values: 11.0–12.5 s) |

11.8 | 11.9 | 12.3 | 12.7a | 13.5a | 13.1a | 12.4 |

| International normalized ratio (INR) (target range for the patient: 1) | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (s) (normal values: 30–40 s) | 27.1b | 27.8b | 28.1b | 28.6b | 29.9b | 21.9b | 27.2b |

|

Fibrinogen (mg/dL) (normal values: 170–410 mg/dL) |

635a | 650a | 701a | 778a | 872a | 317a | 303 |

|

D-dimer (ng/mL) (normal values: <232 ng/mL) |

2109a | 2232a | 2457a | 2446a | 1055a | 2175a | 961a |

|

C-reactive protein (mg/L) (normal values: <5.0 mg/L) |

37.9a | 42.8a | 51.7a | 68.8a | 189.4a | 10.4a | 5.2a |

|

Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) (normal values: 135–225 U/L) |

349a | 365a | 416a | 427a | 418a | 454a | NA |

|

Ferritin (ng/mL) (normal values: 30–400 ng/mL) |

311 | 324 | 356 | 370 | 513a | 346 | 375 |

|

Procalcitoninc(ng/mL) (normal values: <0.5 ng/mL) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.56a | NA | 0.29 |

The value is greater than normal.

The value is less than normal.

Procalcitonin levels measured with chemiluminescence immunoassay.

The patient was treated with Hydroxychloroquine, antiviral drugs (Ritonavir, Darunavir), and Azithromycin, as a standard treatment for COVID-19 pneumonia.1

Three days later, the patient developed a right frontal lobe thromboembolic ischaemic stroke (in the absence of atrial fibrillation or carotid atherosclerosis) and a splenic infarction caused by thrombotic occlusion of the splenic artery.

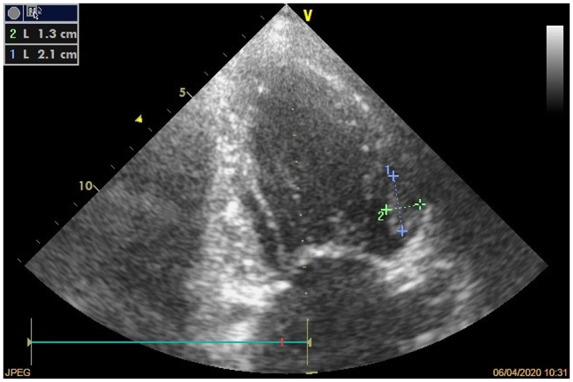

Confirming the abnormal thrombotic diathesis, a TTE detected a mobile, iso-hypoechogenic thrombus attached to the anterior wall of the left ventricle; the thrombus, whose size was 21 mm × 13 mm, was oblong and regular in shape with a large base (Figure 4;Supplementary material online,Video S5); interestingly, the anterior wall had regular contractility, thus confirming the singularity of this thrombotic formation. The test also showed a dilated left ventricle (ESV 170 mL) with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVEF 25%) and diffuse hypokinesia especially regarding the inferior and inferolateral walls.

Figure 4.

Patient no. 2: anterior wall thrombus. Transthoracic echocardiogram shows iso-hypoechogenic thrombus attached to the anterior wall of the left ventricle (dimensions 21 mm × 13 mm).

For a more accurate visualization of the intracardiac thrombus, a second CT scan of the chest was performed on the same day (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Patient no. 2: Computed tomography scan of the chest. Oval-shaped thrombus attached to the anterior wall of the left ventricle.

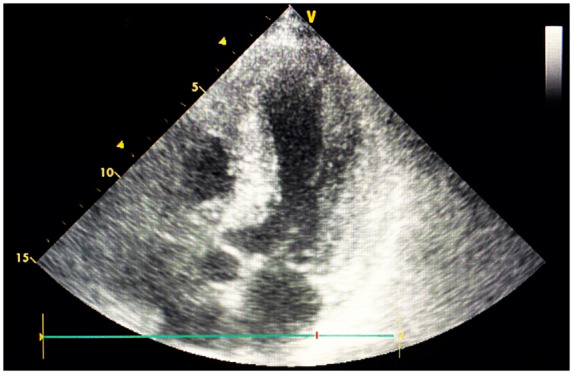

The patient was promptly treated with anticoagulant therapy (Enoxaparin, as aforementioned) and after 12 days a second TTE showed no evidence of the left ventricular thrombus (Figure 6, left;Supplementary material online,Video S6]; moreover, a third CT scan of the chest confirmed its complete dissolution (Figure 6, right). The parenteral anticoagulant therapy was then gradually switched to a long-term oral anticoagulant therapy with warfarin (INR range of 2.0–3.0).

Figure 6.

Patient no. 2: Transthoracic echocardiogram and computed tomography scan after anticoagulant therapy. Transthoracic echocardiogram (left) and computed tomography scan of the chest (right) show no evidence of intracardiac thrombosis after 14 days of anticoagulant therapy.

In the following days, the patient’s clinical and haemodynamic conditions gradually improved, and he was discharged after 21 days of hospitalization. Medical therapy at discharge consisted of Warfarin once daily (dose adjustment based on INR), Ramipril 5 mg once daily, Bisoprolol 1.25 mg once daily, and Rosuvastatin 10 mg once daily.

At a 3-months follow-up visit, the patient was mildly symptomatic for dyspnoea due to the pre-existing heart failure; a TTE confirmed the severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVEF 31%), but without evidence of intracardiac thrombosis.

Discussion

Herein, we describe two patients presenting with intracardiac thrombosis as a complication of COVID-19.

Initially, COVID-19 was thought to primarily affect the upper respiratory tract and the lungs, resulting in fever (88.7% of patients) and cough (67.8%), associated with dyspnoea, pharyngodynia, fatigue, myalgia, and headache.2 Most common severe complications include interstitial pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (which often require mechanical ventilation).2

Growing evidence shows that this viral infection is also responsible for a systemic inflammatory state which results in an abnormal coagulation activation, leading to complications such as arterial and venous thrombosis, intracardiac thrombosis and, in some cases, disseminated intravascular coagulation.3,4 The main explanation for this coagulopathy lies in the dysregulation of the urokinase pathway and plasminogen activity during Coronavirus infections, causing activation of coagulation and hyperfibrinolysis.3,5 A dysregulation of the coagulation cascade is confirmed by higher D-dimer levels, longer prothrombin time, lower fibrinogen and antithrombin levels.3

It has also been proven that COVID-19-related coagulopathy and subsequent complications lead to a longer hospitalization and, in some cases, to death;3,6,7 on the other hand, critically-ill patients often show an increased thrombotic diathesis (with higher D-dimer and lower fibrinogen values).3,7

This evidence has oriented the therapeutical approach, which may include a parenteral anticoagulant drug (such as unfractionated heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin) as a thromboprophylaxis strategy to reduce hospital stay and mortality.1,6

The two patients we described developed a hypercoagulable state which resulted in intracardiac thrombosis, documented by several imaging exams (TTE, CT scan of the chest, cardiac MRI); for both patients, we ruled-out other pre-existing coagulation disorders. After the administration of anticoagulant therapy with Enoxaparin, in both cases, the thrombi dissolved within approximately 2 weeks, without any other major cardiovascular complications.

Conclusions

Abnormal coagulation activation, and specifically intracardiac thrombosis, are fairly common complications of COVID-19, potentially leading to major cardiovascular events and consequently to a poor prognosis.

This evidence highlights the importance of strict monitoring of coagulation parameters (prothrombin time, D-dimer, and fibrinogen levels) and early diagnosis of intracardiac thrombosis through imaging techniques (TTE, CT scan, or cardiac MRI).

Furthermore, we agree with the use of anticoagulant drugs as a thromboprophylaxis strategy, using Heparin at first and then, in the event of intracardiac thrombosis, gradually switching to oral anticoagulants (such as Warfarin) for long-term treatment.

Lead author biography

Emiliano Calvi was born in Turin, Italy on 2 September 1993. He studied Medicine at University of Turin where he completed his Master’s degree in 2018. Since 2019, he is Cardiology resident at Spedali Civili, Brescia (Italy), in the Cardiology Department led by Professor Marco Metra. His main fields of interest are heart failure, echocardiography and arrhythmology.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available atEuropean Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online asSupplementary data.

Consent: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patients in line with COPE guidelines.

Conflict of interest: The Author/s have no conflicts of interest to disclose..

Funding: None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. World Health Organization.Clinical Management of Severe Acute Respiratory Infection When Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Infection is Suspected: Interim Guidance.World Health Organization, Geneva.2020.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331446 (31 January 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang C,Wang Y,Li X,Ren L,Zhao J,Hu Y. et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China.Lancet 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tang N,Li D,Wang X,Sun Z.. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia.J Thromb Haemost 2020;18:844–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lillicrap D. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in patients with 2019-nCoV pneumonia.J Thromb Haemost 2020;18:786–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gralinski LE,Bankhead A 3rd,Jeng S,Menachery VD,Proll S,Belisle SE. et al. Mechanisms of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-induced acute lung injury.mBio 2013;4:e00271–13.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou F,Yu T,Du R,Fan G,Liu Y,Liu Z. et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study.Lancet 2020;395:1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu C,Chen X,Cai Y,Xia J,Zhou X,Xu S. et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China.JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:e200994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.