Abstract

Background

Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and alcohol use disorder (MAUD) are effective and under-prescribed. Hospital-based addiction consult services can engage out-of-treatment adults in addictions care. Understanding which patients are most likely to initiate MOUD and MAUD can inform interventions and deepen understanding of hospitals’ role addressing substance use disorders (SUD).

Objective

Determine patient- and consult-service level characteristics associated with MOUD/MAUD initiation during hospitalization

Methods

We analyzed data from a study of the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT), an interprofessional hospital-based addiction consult service at an academic medical center. Researchers collected patient surveys and clinical data from September 2015 to May 2018. We used logistic regression to identify characteristics associated with medication initiation among participants with OUD, AUD, or both. Candidate variables included patient demographics, social determinants, and treatment-related factors.

Results

339 participants had moderate to severe OUD, AUD, or both and were not engaged in MOUD/MAUD care at admission. Past methadone maintenance treatment (aOR 2.07, 95%CI (1.17, 3.66)), homelessness (aOR 2.63, 95%CI (1.52, 4.53)), and partner substance use (aOR 2.05, 95%CI (1.12, 3.76) were associated with MOUD/MAUD initiation. Concurrent methamphetamine use disorder (aOR 0.32, 95%CI (0.18, 0.56)) was negatively associated with MOUD/MAUD initiation.

Conclusions

The association of MOUD/MAUD initiation with homelessness and partner substance use suggests that hospitalization may be an opportunity to reach highly-vulnerable people, further underscoring the need to provide hospital-based addictions care as a health-system strategy. Methamphetamine’s negative association with MOUD/MAUD warrants further study.

Keywords: opioid-related disorders, alcohol-related disorders, amphetamine-related disorders, addiction medicine, hospitalization, homeless persons

INTRODUCTION

Hospitalization can be a reachable moment to initiate care for people with substance use disorders (SUD) (Englander et al., 2017). Many people with SUD who are admitted to general medical hospitals are not engaged in treatment and they do not come to the hospital seeking addictions care (Englander et al., 2017; Velez et al., 2017). Hospitalization and acute illness can raise patients awareness of mortality and other harmful effects of substance use, and can be a strong motivation to initiate treatment (Velez et al., 2017). Yet, little is known about who might benefit from hospital-based care. Understanding which patients are most likely to initiate MOUD and MAUD can inform interventions and deepen understanding of hospitals’ role addressing substance use disorders (SUD).

Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and alcohol use disorder (MAUD) are effective and under-prescribed. Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) (methadone and buprenorphine) is first-line treatment for moderate to severe opioid use disorder. Decades of evidence show that OAT reduces overdose and all-cause mortality by over half (Sordo et al., 2017), reduces risk of infectious disease transmission (Gowing et al., 2013; Tsui et al., 2014), and reduces criminal behavior associated with substance use (Rastegar et al., 2016). Further, hospitalization is a high-risk touchpoint after which people with opioid use disorder are at increased risk for overdose and death. A recent study in Massachusetts found that hospitalization for injection-related infection was associated with a 54-fold increase in mortality, and that MOUD can mitigate this risk (Larochelle et al., 2019). Medication, combined with psychosocial interventions, comprise first line treatment for moderate to severe alcohol use disorder. MAUD is associated with reduced drinking days, reduced alcohol consumption, and increased abstinence from alcohol (Jonas et al., 2014). Despite their effectiveness, less than 10% of people with alcohol use disorder receive MAUD (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017) and only 20%–40% of people with OUDs are receiving life-saving medication treatment (Jones et al., 2015).

Nationally, hospital-based addiction medicine consult services are emerging as a way to engage out-of-treatment adults in addictions care (Priest and McCarty, 2019). A study at a Boston academic medical center found that 30% of patients with high risk alcohol and drug use were engaged in treatment prior to admission, and that hospital addiction consultation was associated with increased treatment engagement after discharge (Wakeman et al., 2017). In a study of Oregon Medicaid recipients comparing adults seen by our addiction consult service to matched controls, we found that 17% of patients were engaged in treatment prior to hospitalization. Treatment engagement increased to 39% in the 34 days after discharge among patients seen by our addiction consult service, compared to 23% among matched-controls (Englander et al., 2019a). Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) identifies SUD treatment initiation and engagement as a national quality measure (National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2017), and hospitalization is an important part of the SUD care continuum.

Little is known about which hospitalized patients are most likely to initiate MOUD and MAUD, and what consult service factors are associated with medication initiation. The goal of this study was to determine patient- and consult-service level characteristics associated with MOUD and MAUD initiation during hospitalization.

METHODS

Setting and study design

We analyzed survey data collected as part of a study of the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) at an urban, academic medical center in Portland, Oregon. IMPACT is a hospital-based addiction consult service that includes care from addiction medicine providers (physicians or advance-practice providers (APPs)), social workers, and peers with lived experience in recovery (Englander et al., 2017; Englander et al., 2019c). Inpatient medical and surgical providers, and hospital social workers refer patients with known or suspected SUD (excluding people with tobacco use disorders alone) to IMPACT, regardless of an individual’s readiness to change or interest in SUD treatment. In general, at least one member of IMPACT (MD/APP, SW, peer) visits patients daily during hospitalization, and peers often continue peer support 30–90 days after hospital discharge. Peers are often the first-line for patients who express low interest in treatment or working with IMPACT (Collins et al., 2019; Englander et al., 2019b). IMPACT performs an initial comprehensive assessment; elicits patient-centered goals; initiates SUD treatment, including pharmacotherapy and behavioral treatments; and offers harm reduction services. IMPACT can help manage acute pain and perioperative care, including MOUD/MAUD initiation in this population. IMPACT also includes robust referral pathways to post-hospital SUD care. IMPACT offers MOUD and MAUD to all patients with moderate-to-severe opioid and/or alcohol use disorder, and tailors medication decisions based on patient preferences, acute medical conditions, and post-hospital community treatment resources. For some patients, this includes coordinating treatment plans with skilled nursing facilities (e.g. coordinating take-out dosing from an opioid treatment program (OTP) or daily transportation to support patients to get methadone from an OTP while at SNF). The Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Participants

Participants included patients seen by IMPACT and enrolled in the IMPACT evaluation between September 2015 and August 2018. Patients were eligible for this analysis if they 1) had moderate to severe opioid use disorder, alcohol use disorder, or both, and 2) were not already receiving MOUD or MAUD upon hospital admission. We operationalized the definition of current use of MOUD or MAUD by baseline questionnaire responses, which asked participants if they were currently receiving medication for opioid use disorder (e.g. methadone, buprenorphine, naltrexone), or medication for alcohol use disorder (e.g. acamprosate).

Study procedures and data sources

Early in hospitalization, a trained research assistant who was not part of the clinical team administered an in-person survey. Surveys focused on demographics, substance use, and patient experience, and took approximately 15–20 minutes to complete. The research assistant collected patient surveys and directly entered responses into an online survey and database management system, REDCap, reviewing surveys afterwards for accuracy. At discharge, IMPACT clinical team members completed a case closure form during the daily team huddle. Case closure forms included information about a patient’s diagnoses, hospital course, and treatment plan. Trained research assistants validated information from case closure forms by chart review in the electronic health record, and then entered this information into REDCap. Finally, research team members abstracted data from electronic medical records.

Measures

We selected potential covariates based on a priori hypotheses and face validity

Covariates from the patient survey included gender (male/female), race (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, African American/Black, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander, white, more than one race, refused), income in the previous year ($10,000 increments, $0 to >$50,000), housing status (housed/unhoused), partner with substance use (yes/no), rural home zip code (yes/no), history of past but not current methadone maintenance engagement (yes/no) and access to a usual primary care clinic (yes/no). We identified rural zip codes using the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy designated rural zip codes (Health Resources & Services Administration, 2018). We determined past but not current methadone maintenance therapy using the Addiction Severity Index Lite (ASI-lite) measurement tool; and considered patients who identified past methadone maintenance therapy without use in the last 30 days (Cacciola et al., 2007). Covariates from the case closure form included opioid use disorder (yes/no), alcohol use disorder (yes/no), methamphetamine use disorder (yes/no), peer support delivered in hospital (yes/no). Discussion with members of the clinical and research team suggested that cocaine and benzodiazepine use would be very low in our population; hence, we did not consider these covariates in our research. Covariates from chart review included patient age (years), insurance status (any Oregon Medicaid, Medicare, other), and number of IMPACT clinician and social worker visits per day (continuous).

Our outcome measure was in-hospital initiation of MOUD, MAUD, or both, and was determined from case closure forms and validated via chart review. MOUD included the three FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder: methadone, buprenorphine (including buprenorphine-naloxone), and naltrexone. MAUD included naltrexone, acamprosate, disulfiram, and gabapentin. We included gabapentin only if it was prescribed for treatment of alcohol use disorder. We elected to include gabapentin even though it is a not FDA approved for treatment of AUD because in hospitalized adults with AUD and acute pain on opioids who are reluctant to take multiple three-time daily medication, it can be the best alternative for MAUD. We felt including it was better reflective of MAUD initiation than excluding it. We excluded all medications if there was no plan to continue after hospital discharge; for example, methadone for withdrawal only with no plan for methadone maintenance post-discharge.

Covariate manipulation

We reclassified race as Caucasian/non-Caucasian because of sample size among non-Caucasian patients; we included patients who did not know their race, were missing race information or refused to answer as Caucasian. One participant was transgender; we reclassified this person the gender they identify with. If participants were unsure if they had any income in the previous year, we classified them as no income.

Finally, we created a “dose indicator” for IMPACT delivery, defined as the total number of documented IMPACT provider or social worker encounters during hospitalization, divided by the total number of hospital days. We dichotomized this as a binary covariate (at least 1 visit per day/less than 1 visit per day). We report this variable in our table but did not consider this for inclusion in our analyses, as it may be challenging to interpret without a measure of patient motivation for treatment and could represent confounding by indication.

We were concerned that medication initiation would differ significantly by diagnosis (AUD, OUD or both). We chose to include an interaction term to determine if IMPACT delivery differed by diagnosis; if the interaction term was significant, we planned to present the terms separately in the paper.

Data analysis

Primary analysis and fit

We built a logistic regression model to estimate the relationship of baseline participant characteristics with the binary outcome variable MOUD and/or MAUD initiation. We fit our logistic regression model using a conservative estimated covariate ratio of 10 events per degree of freedom (Cacciola et al., 2007). We used backwards stepwise elimination with a relaxed p-value of 0.20 to finalize our model and did not force any covariates into our model. We evaluated our continuous covariates for linearity in the log-odds using Lowess scatter plot (comparing medication intention and continuous covariates individually and evaluated all covariates for collinearity using a correlation matrix). Finally, we used a Hosmer-Lemeshow test to evaluate model goodness-of-fit (Hosmer and Lemeshow, 2000).

For patients who were admitted more than once, we used only the first encounter to both comply with the assumption of independence in logistic regression testing and because we were primarily interested in associations with MOUD/MAUD initiation following a first encounter with IMPACT. We did not adjust for multiple comparisons in this exploratory study.

Missing Data

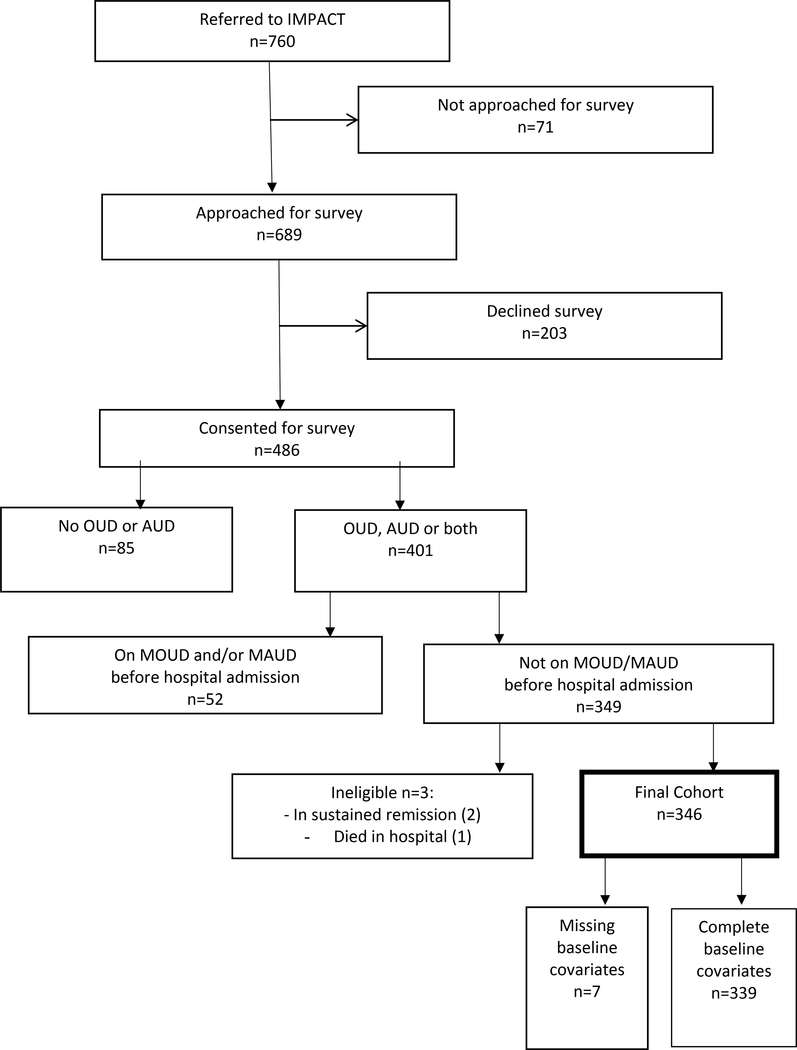

We anticipated minimal missingness in surveys conducted in the hospital, and so only included patients with complete covariate data, other than as listed in data manipulations above (Figure).

Figure 1.

Participant flowchart

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, we identified influential observations using Pregibon’s Delta-Beta statistic. Observations with a Delta-Beta statistic greater than 0.20 were removed. Second, we re-ran our analyses without imputing Caucasian when race was missing. We planned to report results alongside the primary analysis if directionality or significance of any covariate changed.

RESULTS

During the study period, 760 patients were referred to IMPACT. Researchers approached 689 patients, and 486 consented to participate in surveying. Of those, 401 had moderate to severe OUD and/or AUD and 349 had no pharmacotherapy for OUD/AUD before admission (Figure). Two patients were identified as in “sustained remission” from both alcohol and opioid use and were excluded. One patient died in the hospital. 346 participants were eligible for inclusion in the model. Of those, 248 (71.7%) initiated MOUD/MAUD during hospitalization. Study participants were predominantly Caucasian (80.9%), had opioid use disorder without alcohol use disorder (52.0%), were experiencing homelessness (55.0%), had Medicaid insurance (76.3%), and had an established primary care clinic (61.3%). 30.0% of participants had a co-occurring moderate or severe methamphetamine use disorder (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics among IMPACT patients with OUD, AUD or both, 2015 to 2018

| Total sample (n=346) | Medication plan at discharge (n=248) | No medication plan at discharge (n=98) | Univariate p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 43.5 (12.8) | 44.2 (12.9) | 41.8 (12.3) | 0.11 |

| Male gender (n=343) | 218 (63.0%) | 153 (61.7%) | 65 (66.3%) | 0.40 |

| Caucasian race | 280 (80.9%) | 199 (80.2%) | 81 (82.7%) | 0.61 |

| Opioid Use Disorder (without alcohol use disorder) | 180 (52.0%) | 125 (50.4%) | 55 (56.1%) | 0.34 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder (without opioid use disorder) | 127 (36.7%) | 90 (36.3%) | 37 (37.8%) | 0.80 |

| Both Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders | 39 (11.3%) | 33 (13.3%) | 6 (6.1%) | 0.06 |

| History of past methadone maintenance | 126 (36.4%) | 100 (40.3%) | 26 (26.5%) | 0.02 |

| Co-occurring methamphetamine use disorder | 104 (30.0%) | 61 (24.6%) | 43 (43.9%) | <0.001 |

| No income in previous year | 195 (56.4%) | 141 (56.9%) | 54 (55.1%) | 0.53 |

| $1 to $10,000 | 45 (13.0%) | 31 (12.5%) | 14 (14.3%) | |

| $10,001 to $20,000 | 50 (14.5%) | 37 (14.9%) | 13 (13.3%) | |

| $20,001 to $30,000 | 20 (5.8%) | 16 (6.5%) | 4 (4.1%) | |

| $30,001 to $40,000 | 5 (1.4%) | 3 (1.2%) | 2 (2.0%) | |

| $40,001 to $50,000 | 6 (1.7%) | 4 (1.6%) | 2 (2.0%) | |

| >$50,000 | 25 (7.2%) | 16 (6.5%) | 9 (9.2%) | |

| Current Homelessness (n=340) | 192 (55.5%) | 149 (60.1%) | 43 (43.9%) | 0.004 |

| Partner with substance use (n=348) | 101 (29.2%) | 82 (33.1%) | 19 (19.4%) | 0.01 |

| Rural zip code | 63 (18.2%) | 44 (17.7%) | 19 (19.4%) | 0.72 |

| Medicaid | 264 (76.3%) | 194 (78.2%) | 70 (71.4%) | 0.18 |

| Peer support in hospital | 105 (30.3%) | 79 (31.9%) | 26 (26.5%) | 0.33 |

| Established primary care clinic (n=344) | 212 (61.3%) | 155 (62.5%) | 57 (58.2%) | 0.40 |

| 1 or more IMPACT clinical encounters per day | 111 (32.1%) | 88 (35.5%) | 23 (23.5%) | 0.03 |

values shown are n (%) or mean (SD). OUD = opioid use disorder; AUD = alcohol use disorder

In our analysis, past methadone maintenance treatment initiation (aOR 2.24, 95%CI (1.28, 3.94)), homelessness (aOR 2.52, 95%CI (1.47, 4.30)), and having a partner with substance use (aOR 2.06, 95%CI (1.13, 3.74were associated with MOUD/ MAUD initiation. Concurrent methamphetamine use disorder (aOR 0.32, 95%CI (0.18, 0.56)) was negatively associated with MOUD/MAUD initiation (Table 2). In addition to these covariates, backwards selection also included age and gender in our final model, though they are not statistically significant. Neither sensitivity analysis changed the direction or significance of results. The interaction term evaluating if the IMPACT dose indicator varied by diagnosis (AUD only vs any OUD) was not significant, and was not included in the final model (p=0.97).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models of medication initiation among IMPACT patients with OUD, AUD or both, 2015 to 2018

| Unadjusted Odds Ratios (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratios (95% CI) * | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.01 (0.996, 1.03) | 1.02 (0.997, 1.04) |

| Male gender | 1.23 (0.75, 2.03) | 1.50 (0.87, 2.58) |

| Concurrent methamphetamine use disorder | 0.42 (0.25, 0.68) | 0.32 (0.18, 0.56) |

| Ever received methadone | 1.87 (1.12, 3.13) | 2.24 (1.28, 3.94) |

| Current homelessness | 1.99 (1.24, 3.21) | 2.52 (1.47, 4.30) |

| Partner with substance use | 2.07 (1.17, 3.64) | 2.06 (1.13, 3.75) |

IMPACT = Improving Addiction Care Team; OUD = opioid use disorder; AUD = alcohol use disorder

Only covariates listed in Table 2 were included in the final adjusted model

Among participants with any OUD (n=219), methadone was the most common MOUD (n=80; 36.5%), followed by buprenorphine (n=62, 28.3%). Eight participants with OUD (3.7%) received intramuscular naltrexone. Among participants with any AUD (n=166), 41 (24.7%) received any naltrexone (oral or intramuscular), and 39 (23.5%) received acamprosate (Table 3).

Table 3.

Medication initiation by substance use disorder and medication type

| All participants (n=346) | Opioid use (with no alcohol) (n=180) | Alcohol use (with no opioid use) (n=127) | Opioid and alcohol use (n=39) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methadone | 80 (23.1%) | 71 (39.4%) | 0 | 9 (23.1%) |

| Buprenorphine-naloxone | 62 (17.9%) | 49 (27.2%) | 0 | 13 (33.3%) |

| Naltrexone oral | 23 (6.6%) | 1 (0.6%) | 20 (15.7%) | 2 (5.1%) |

| Naltrexone IM | 23 (6.6%) | 4 (2.2%) | 15 (11.8%) | 4 (10.3%) |

| Acamprosate | 39 (11.3%) | 0 | 36 (28.3%) | 3 (7.7%) |

| Gabapentin | 21 (6.1%) | 0 | 19 (15.0%) | 2 (5.1%) |

| Total receiving medication | 248 (71.7%) | 125 (69.4%) | 90 (70.9%) | 33 (84.6%) |

IM = intramuscular injection

Discussion

Our study identifies predictors of MOUD and/or MAUD initiation among hospitalized adults seen by an addiction consult service. We found that current homelessness or a partner with substance use predicted MOUD/MAUD initiation. Co-occurring methamphetamine use disorder, however, was negatively associated with MOUD/MAUD initiation. Residing in a rural area, having a usual source of primary care, and Medicaid insurance had no association with MOUD/MAUD initiation. To our knowledge, this is the first study describing patterns of MOUD/MAUD initiation among hospitalized adults seen by an addiction consult service. Our findings suggest ways in which hospital-based addiction care may differ from community treatment, and highlight how the reachable moment of hospitalization may differentially effect people with co-occurring methamphetamine use, those experiencing homelessness or those with a partner with substance use.

This research builds on existing research in several important ways. The findiang that 74% of people with moderate to severe OUD and/or AUD initiated medication supports earlier work showing that hospitalization can be a reachable moment and opportunity engage non-treatment seeking adults by interrupting drug use and serving as a “wakeup call” (Velez et al., 2017). Though this study was not designed to examine post-hospital treatment engagement, our findings are contextualized and promising in light of earlier work showing that hospital-initiated addictions care is associated with increased treatment engagement after discharge (Englander et al., 2019a).

This study highlights ways in which hospitalization may present a unique opportunity to initiate care. Notably, most research in community settings suggests that homelessness is associated with lower MOUD/MAUD initiation and engagement (Appel et al., 2004; Prangnell et al., 2016; Damian et al., 2017; Lo et al., 2018; Watkins et al., 2018), and some studies find no association (Simon et al., 2017; Tsui et al., 2018). Previous studies in community settings found that having a partner with substance use is associated with lower readiness to engage in treatment (Riehman et al., 2000). By contrast, our study found increased rates of MOUD/MAUD initiation in this population. Though we do not have data to explain this unexpected finding, we speculate that there may be an important interplay between motivation to initiate treatment and barriers to care. Specifically, patients with fewer barriers who are motivated to initiate treatment may do so prior to hospitalization. Our findings suggest that hospitalization may serve as an opportunity to engage hard-to-reach populations.

The finding that co-occurring methamphetamine use disorder is negatively associated with MOUD/ MAUD initiation is important. Methamphetamine hospitalizations are surging (Winkelman et al., 2018) and methamphetamine use is an emerging public health issue, with an estimated 250% increase in stimulant-related deaths nationally from January 2015 to October 2018 (Ahmad et al., 2019). In Oregon, rates appear even worse, with a 400% increase in deaths related to methamphetamines between 2010 and 2018 (Oregon-Idaho HIDTA Program, 2019).

Little is known about the association of methamphetamine use and treatment with medications for opioid and alcohol use in general, and specifically among hospitalized adults. However, our research is consistent with earlier work in community settings. One study of clients with opioid and methamphetamine use who accessed services across 17 Washington State syringe exchanges found that recent methamphetamine use was negatively associated with interest in getting help for OUD (AOR = 0.49; 95% CI: 0.26, 0.91) (Frost et al., 2018). Another primary care based study among people with OUD and recent stimulant use found that clinic policies eliminating the requirement for stimulant abstinence were associated with higher rates of buprenorphine initiation, but also with lower buprenorphine treatment retention (Payne et al., 2019).

The negative association of methamphetamine use with MOUD/MAUD initiation warrants further exploration, and could be due to a variety of system-, provider-, or patient-factors. We speculate that patients with methamphetamine use may perceive their alcohol and/or opioid use as secondary and not needing MOUD/MAUD or that methamphetamine withdrawal, cravings, or psychiatric symptoms may interfere with patients or providers’ ability to initiate MOUD/MAUD. It is also possible that community SUD treatment policies influence patients’ decisions about MOUD/MAUD, as methadone and buprenorphine treatment programs commonly dismiss patients if their urine drug screens result positive for methamphetamine. Though unknown, it is also possible that methamphetamine use is a marker for social marginalization or other factors that might make people less likely to initiate MOUD/MAUD. Co-use of methamphetamines and opioids is increasingly common due to synergistic euphoric or balancing effects; easier access to methamphetamine; social pressures to co-use; and co-use as a marker for more severe SUD (Ellis et al., 2018). How these factors effect non-treatment seeking, hospitalized adults remains unclear.

This study has several limitations. It is a single-site study and all patients received care from an addiction consult service. Findings may not be transferable to settings without a consult service or where the consult service is comprised of different team members or has different activities. Second, not all IMPACT patients agreed to participate in the survey. It is possible that people who participated were more or less likely to initiate MOUD/MAUD. Further, this study took place in Oregon and participants had low racial and ethnic diversity. Additionally, we asked patients about past methadone use because this is included in the ASI-lite, but we did not ask about other past MOUD or MAUD exposure. Associations between all types of past MOUD/MAUD treatment may be important to test in predicting hospital MOUD/MAUD in future studies. Further, our analysis not adjust for multiple comparisons as the nature of this work was exploratory. Additionally, we looked only at the association of MOUD/MAUD initiation following a first encounter with IMPACT. Future research should explore effects of repeated exposure to addiction consult services for individuals who are readmitted to hospitals and have repeat addiction consultation. Future studies should also explore additional patient- and consult-service factors that promote MOUD/MAUD initiation such as patient readiness to change. This analysis included all participants regardless of AMA discharge. Our hypothesis is that AMA discharge would be strongly predictive of not initiating MOUD/MAUD with a plan to continue; future studies could explore this more closely. Finally, while important, medication initiation does not reflect long-term treatment engagement. Future studies of treatment engagement and retention specific to MOUD/MAUD will be important.

Our study has several important implications for clinical care and research. First, the findings that homelessness and having a partner with substance use was positively associated with MOUD/MAUD initiation suggests that these vulnerable people may not be accessing treatment outside of the hospital. It also supports the potential value of an interprofessional hospital-based addictions team with resources dedicated to addressing social factors that may influence treatment retention after discharge. For IMPACT, this includes social workers and peers who work to connect people with housing, engage partners in addictions care, develop relapse prevention plans, and tailor post hospital treatment plans to support retention in care. Our findings also have implications for community treatment, highlighting the importance of addressing social determinants of health across the continuum of hospital and community SUD to support treatment engagement and retention.

The fact that methamphetamine use is associated with lower MOUD/MAUD initiation is important, especially as we consider drivers for the opioid overdose crisis. Most opioid overdose deaths involve multiple substances (Barocas et al., 2019) and initiation of MOUD during acute care encounters is critical to overdose prevention (Larochelle et al., 2018). Our findings suggest the need for further research to explore the association of methamphetamine use and MOUD, MAUD, and hospital-based addiction medicine care. Future studies should also examine effect of MOUD/MAUD initiation during hospitalization on pertinent clinical outcomes including substance use, long-term SUD treatment engagement, healthcare utilization, quality of life, overdose risks, and other health outcomes.

Acknowledgements

IMPACT is funded by Oregon Health & Science University and CareOregon. Authors would like to acknowledge the entire IMPACT clinical and research teams. This publication was made possible with support from the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute (OCTRI), grant number UL1TR002369 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. This work was presented as an oral research presentation at the AMERSA national conference on November 9, 2019 in Boston, MA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No author has any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Ahmad FB, Escobedo LA, Rosse LM, Spencer MR, Warner M, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm. Accessed August 6, 2019.

- 2.Appel PW, Ellison AA, Jansky HK, Oldak R. Barriers to enrollment in drug abuse treatment and suggestions for reducing them: opinions of drug injecting street outreach clients and other system stakeholders. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2004;30:129–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barocas JA, Wang J, Marshall BDL, et al. Sociodemographic factors and social determinants associated with toxicology confirmed polysubstance opioid-related deaths. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;200:59–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Lin YT, Lynch KG. Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of a “lite” version of the Addiction Severity Index. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007;87:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins D, Alla J, Nicolaidis C, et al. “If it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have talked to them”: qualitative study of addiction peer mentorship in the hospital. J Gen Intern Med 2019;September 11. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05311-0. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damian AJ, Mendelson T, Agus D. Predictors of buprenorphine treatment success of opioid dependence in two Baltimore city grassroots recovery programs. Addict Behav 2017;73:129–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellis MS, Kasper ZA, Cicero TJ. Twin epidemics: the surging rise of methamphetamine use in chronic opioid users. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;193:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Englander H, Dobbertin K, Lind BK, et al. Inpatient addiction medicine consultation and post-hospital substance use disorder treatment engagement: a propensity-matched analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2019a;August 13. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05251-9. [Epub adhead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Englander H, Gregg J, Gullickson J, et al. Recommendations for integrating peer mentors in hospital-based addiction care. Subst Abus 2019b;September 6:1–6. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2019.1635968. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Englander H, Mahoney S, Brandt K, et al. Tools to support hospital-based addiction care: core components, values, and activities of the Improving Addiction Care Team. J Addict Med 2019c;13:85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med 2017;12:339–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frost MC, Williams EC, Kingston S, Banta-Green CJ. Interest in getting help to reduce or stop substance use among syringe exchange clients who use opioids. J Addict Med 2018;12:428–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowing LR, Hickman M, Degenhardt L. Mitigating the risk of HIV infection with opioid substitution treatment. Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:148–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resources Health & Administration Services. Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP) Data Files. Available at: https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/datafiles.html. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- 15.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistical Regression, 3rd Edition. New York: Wiley, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2014;311:1889–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones CM, Campopiano M, Baldwin G, McCance-Katz E. National and state treatment need and capacity for opioid agonist medication-assisted treatment. Am J Public Health 2015;105:e55–e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larochelle MR, Bernson D, Land T, et al. Medication for opioid use disorder after nonfatal opioid overdose and association with mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:137–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larochelle MR, Bernstein R, Bernson D, et al. Touchpoints - opportunities to predict and prevent opioid overdose: a cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;204:107537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lo A, Kerr T, Hayashi K, et al. Factors associated with methadone maintenance therapy discontinuation among people who inject drugs. J Subst Abuse Treat 2018;94:41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Initiation and Engagement of Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse or Dependence Treatment (IET). Available at: https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/initiation-and-engagement-of-alcohol-and-other-drug-abuse-or-dependence-treatment/. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- 22.Oregon-Idaho HIDTA Program. Program Year 2020 Drug Threat Assessment Program. Available at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/579bd717c534a564c72ea7bf/t/5d08088507db5c0001ed3f21/1560807567416/PY+2020+OREGON-IDAHO+HIDTA+Threat+Assessment_FINAL_061719.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- 23.Payne BE, Klein JW, Simon CB, et al. Effect of lowering initiation thresholds in a primary care-based buprenorphine treatment program. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;200:71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prangnell A, Daly-Grafstein B, Dong H, et al. Factors associated with inability to access addiction treatment among people who inject drugs in Vancouver, Canada. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2016;11:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med 2019;13:104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rastegar DA, Sharfstein Kawasaki S, King VL, Harris EE, Brooner RK. Criminal charges prior to and after enrollment in opioid agonist treatment: a comparison of methadone maintenance and office-based nuprenorphine. Subst Use Misuse 2016;51:803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riehman K, Hser Y-I, Zeller M. Gender differences in how intimate partners influence drug treatment motivation. J Drug Issues 2000;30:823–838. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon CB, Tsui JI, Merrill JO, Adwell A, Tamru E, Klein JW. Linking patients with buprenorphine treatment in primary care: predictors of engagement. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;181:58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2017;357:j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. SMA 17–5044, NSDUH Series H-52). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2016/NSDUH-FFR1-2016.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsui JI, Burt R, Thiede H, Glick SN. Utilization of buprenorphine and methadone among opioid users who inject drugs. Subst Abus 2018;39:83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsui JI, Evans JL, Lum PJ, Hahn JA, Page K. Association of opioid agonist therapy with lower incidence of hepatitis C virus infection in young adult injection drug users. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1974–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s been an experience, a life learning experience”: a qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:296–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, Rigotti NA. Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:909–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watkins KE, Ober A, McCullough C, et al. Predictors of treatment initiation for alcohol use disorders in primary care. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;191:56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winkelman TA, Admon LK, Jennings L, Shippee ND, Richardson CR, Bart G. Evaluation of amphetamine-related hospitalizations and associated clinical outcomes and costs in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e183758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]