Abstract

Background

Mesalazine is a well-established 1st line treatment for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Cardiotoxicity following 5-aminosalicyclic-acid therapy remains a rare yet serious complication and can often be challenging to distinguish from myocarditis presenting as an extra-intestinal manifestation of IBD.

Case summary

We present a case of a 22-year-old man with a background of ulcerative colitis commenced on a mesalazine preparation for disease progression. He presented to our hospital 12 days following drug initiation with acute chest pain, peak troponin-T of 242 ng/L, dynamic electrocardiogram changes, and severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction on transthoracic echocardiogram. The clinical diagnosis of myopericarditis was suspected and mesalazine was stopped shortly after. Outpatient cardiac magnetic resonance performed 2 weeks following mesalazine cessation demonstrated a recovery of cardiac function with associated symptom and biochemical resolution.

Discussion

Clinicians should be aware of this potentially fatal adverse effect of a commonly prescribed medication. Symptoms of myocarditis often occur within the early stages of mesalazine initiation, which aids the clinical diagnosis. The mainstay of treatment is to simply discontinue the drug with rapid resolution of symptoms seen without any permanent or long-term cardiac dysfunction. Close liaison with the gastroenterology team is key, as 2nd line IBD therapies are often required for the ongoing management of the patient’s colitis.

Keywords: Myocarditis, Myopericarditis, 5-aminosalicyclic-acid (5-ASA), Mesalazine, Cardiotoxicity, Inflammatory bowel disease, Case report

Learning points

Mesalazine can cause myocarditis early after initiation.

Clinicians should be aware of the non-infectious causes of myocarditis which would influence management.

Discontinuation of mesalazine remains the mainstay of treatment with cardiac dysfunction shown to return to baseline functioning.

Introduction

Mesalazine is an established 1st line therapy for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and is a common prescription due to a favourable safety profile with proven efficacy in active disease as well as maintaining remission and quiescence.1 Adverse side effects are rare but include agranulocytosis, pancreatitis, peripheral neuropathy, and cardiac inflammation.2 Cardiotoxicity following administration of mesalazine is a potentially fatal complication with a reported incidence up to 0.3%.3,4 Myocarditis may also present as an extra-intestinal manifestation of IBD which can often be challenging to differentiate from 5-aminosalicyclic-acid (5-ASA)-induced myocarditis. We present a case of a 22-year-old man with acute myopericarditis soon after mesalazine initiation.

Timeline

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 2012 | Diagnosis of limited proctitis with minimal symptoms. A watchful wait approach taken. |

| Early-Mid 2019 | Relapse of acute colitis requiring oral steroids. Repeat flexible sigmoidoscopy (FOS) arranged to assess disease extent. |

| 12 days prior to admission | FOS → active disease to the splenic flexure. Patient commenced on a mesalazine preparation alongside weaning prednisolone course. |

|

Admission Day 0 |

Presentation with acute chest pain, dyspnoea, and lethargy. Electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated concave ST-segment elevation laterally evolving into T-wave inversion. Blood profile showed a peak troponin-T of 242 ng/L. |

| Day 1–3 |

Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) demonstrated severe left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction. Diagnosis of myocarditis made and medical therapy for heart failure (HF) commenced. Discharged with planned outpatient cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR). |

| 2 weeks |

Nurse-led HF clinic review; reported ongoing dyspnoea and chest pain. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and beta blocker up-titrated. |

| 4 weeks | Liaison with gastroenterology team and mesalazine stopped as suspected causative agent of myocarditis. Remained on weaning prednisolone course. |

| 5 weeks | Nurse-led HF clinic review; symptoms settling with improving exercise tolerance and fewer episodes of chest pain. |

| 6 weeks | CMR → recovered cardiac function with no active inflammation or fibrosis. |

| 8 weeks |

Cardiology clinic review; resolved symptoms, no further chest pain and return to baseline exercise tolerance. Resolution of ECG T-wave inversion and repeat troponin-T measured at <5 ng/L. |

| 5 months | Surveillance TTE demonstrated ongoing preserved LV systolic function. |

Case presentation

A 22-year-old Caucasian non-smoker male presented to our hospital with sudden onset left-sided chest pain radiating to the shoulder tip. The pain was sharp in nature and exacerbated by deep inspiration and supine positioning. He also complained of preceding dyspnoea and general fatigue. There was no associated cough, fever, or coryzal prodrome. Past medical history included ulcerative colitis (UC) diagnosed at age 17. A watchful wait approach had been taken due to limited proctitis, however symptoms relapsed in the months prior to admission and he required multiple steroid courses. A repeat flexible sigmoidoscopy demonstrated active disease to the splenic flexure and a mesalazine preparation was commenced 12 days prior to presentation alongside a weaning course of steroids. Despite this, his colitis was still flaring on arrival to hospital with generalized abdominal pain, increased frequency, and bloody diarrhoea. Family history was strong for unprovoked deep vein thrombosis in his mother and maternal grandfather. Medication history on admission included mesalazine 1.6 g b.i.d. and prednisolone 40 mg.

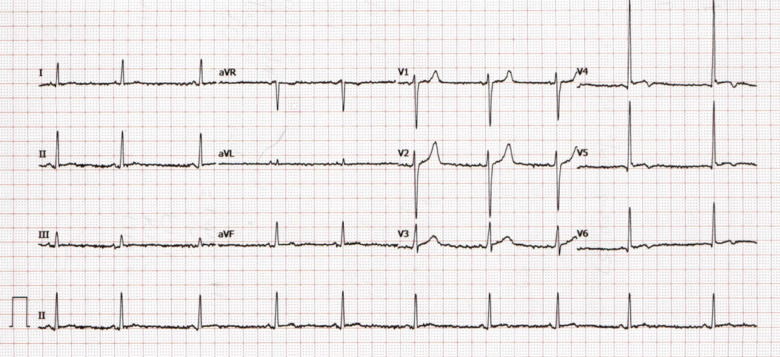

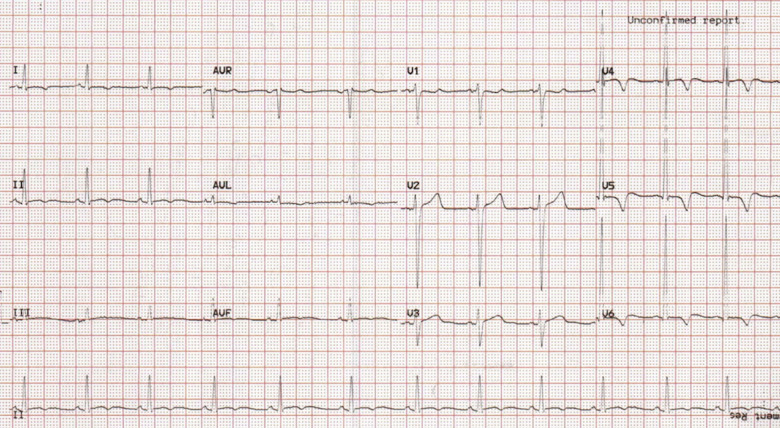

On arrival, he was afebrile, normotensive with normal oxygen saturations. Cardio-respiratory examination was unremarkable. Chest X-ray demonstrated clear lung fields. Blood profile revealed an elevated white cell count of 19.46 × 109/L (normal: 4–11 × 109/L), D-dimer of 1.81 mg/L (normal: <0.50 mg/L), troponin-T of 209 ng/L (normal: <14ng/L), and normal serum electrolytes. Resting 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) (Figure 1) demonstrated sinus rhythm and concave ST-segment elevation in leads V4–V6 with associated biphasic T-waves. He suffered ongoing chest pain during the first 24 h of presentation and repeat ECG (Figure 2) demonstrated dynamic T-wave inversion in leads I, aVL, and V4–V6. Repeat troponin-T was recorded at 242 ng/L. He was initially treated as a suspected pulmonary embolus and transferred to the cardiology ward.

Figure 1.

Admission electrocardiogram demonstrating sinus rhythm with concave ST-elevation in V4–V6 with associated biphasic T-waves.

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram 24 h after admission demonstrating sinus rhythm with dynamic T-wave inversion in leads I, aVL, and V4–V6.

Upon review by the cardiology team, the working impression was a viral-induced myocarditis. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) demonstrated a non-dilated but severely impaired left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic function with global hypokinesia; mitral annular plane systolic excursion was reduced at 4 mm (normal: ≥10 mm), mitral valve deceleration time was 121 ms with an average e′ of 7 cm/s and E/e′ of 13. Right ventricle was non-dilated with a preserved radial and longitudinal systolic function; tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion was 17 mm (normal: ≥16 mm) with a tricuspid annular systolic velocity of 12 cm/s. No pericardial effusion or significant valve defects were seen (Video 1).

Following the TTE findings, our patient was commenced and titrated on standard heart failure (HF) treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ramipril 1.25 mg) and a beta blocker (bisoprolol 2.5 mg). He was clinically euvolaemic and did not require any diuretic therapy during his admission. The patient stabilized and was discharged with a planned early outpatient cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) at the local tertiary centre and close HF clinic surveillance. His prednisolone remained at 40 mg with a planned reduction of 5 mg weekly.

Ten days following discharge, he was reviewed in the nurse-led HF clinic where he reported ongoing episodes of chest pain with a reduced exercise tolerance. His HF medications were up-titrated and shortly after, his mesalazine was discontinued after liaison with the gastroenterology team as the suspected causative agent to his myopericarditis. A further follow-up was arranged 10 days following mesalazine cessation where he reported a markedly improved exercise tolerance with milder episodes of chest pain. At the time, he was on a weaning regime of prednisolone at a dose of 20 mg.

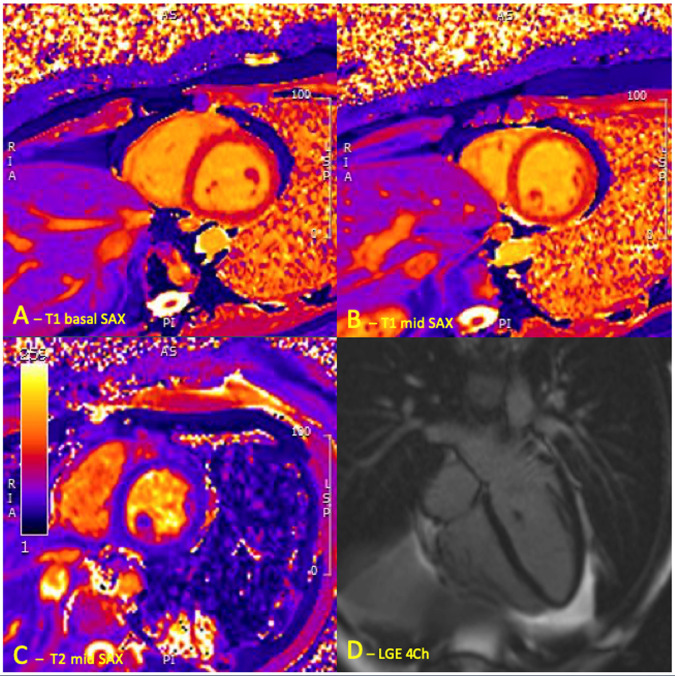

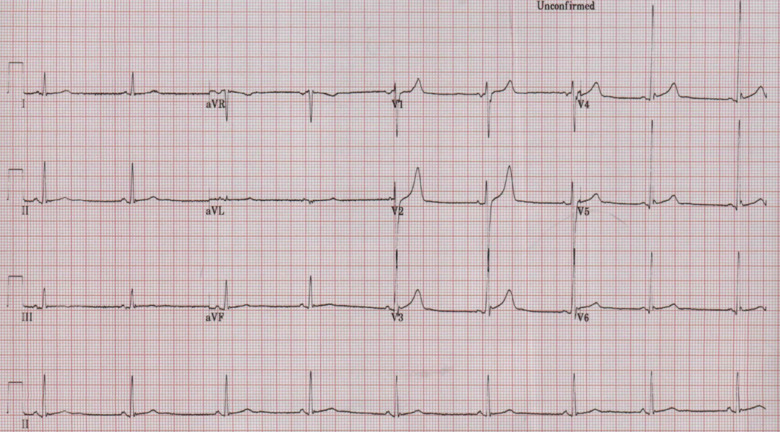

CMR was conducted 2 weeks following cessation of mesalazine (6 weeks following admission) and demonstrated a normal biventricular systolic function with no myocardial scarring or fibrosis. No active myocardial inflammation was demonstrable with no abnormal elevation of T1 (980 ms at 1.5 T) or T2 values on T1 and T2 mapping (Figure 3). Upper limit of normal value for our 1.5 T Siemens Avanto magnetic resonance imaging scanner is 980 ms and 60 ms for T1 and T2 relaxation values respectively. A further consultation took place shortly after and the patient reported he was pain free, no longer breathless and exercise capacity had returned to baseline. Prednisolone dose had been further reduced and repeat ECG demonstrated sinus rhythm with upright T-waves (Figure 4) with troponin-T measuring <5 ng/L; signifying no ongoing myocardial inflammation. Surveillance echocardiogram 4 months later demonstrated an ongoing preserved and recovered LV systolic function (Video 2) and his IBD was now controlled on infliximab therapy.

Figure 3.

Cardiac magnetic resonance performed 2 weeks following discontinuation of mesalazine demonstrating no active myocarditis. T1 colour maps (A and B). (A) Basal SAX. (B) Mid SAX. (C) T2 colour map SAX. (D) 4Ch late gadolinium enhancement.

Figure 4.

Repeat electrocardiogram in the outpatients following cessation of mesalazine with recovered T-wave inversion.

Discussion

Cardiac extra-intestinal features of IBD are rare but may include dysrhythmias, pericardial disease, myocarditis, endocarditis, and conduction tissue disease.5 It is well documented that patients with IBD have a higher risk of developing myocarditis compared with the background population; a 16-year Danish Cohort study gave a risk of 4.6 per 100 000 years of risk for development of myocarditis in patients with chronic inflammatory colitis.6 The incidence rate ratio for developing myocarditis was 8.3 in Crohn’s disease and 2.6 in UC when compared with the general population.6

Even though cardiotoxicity following mesalazine is rare with a reported incidence of up to 0.3%,3,4 it can prove fatal with data showing 30% of biopsy proven myocarditis progressing to a dilated cardiomyopathy, which carries a poor prognosis.7 Myocarditis as part of IBD can often be challenging to distinguish from 5-ASA mediated myocarditis. However, it is vital for clinicians to be aware of this adverse effect to allow prompt recognition and cessation of mesalazine prior to the development of any long-term dysfunction.

IBD associated myocarditis involves an autoimmune response following autoantigen exposure,8 whereas the mechanism of mesalazine-induced cardiotoxicity is thought to be a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction; supported by eosinophilic infiltration on endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) specimens, rapid recovery of symptoms following drug discontinuation and freedom from permanent sequalae.9

Diagnosis of 5-ASA-induced myocarditis is based on clinical grounds; with symptom onset typically occurring within the first 2–4 weeks of mesalazine initiation.10,11 Treatment is largely supportive with drug cessation being key with complete resolution of symptoms and cardiac dysfunction documented within the days following drug withdrawal.11,12 In addition, steroids are shown to aid and expedite myocardial recovery.13

Our patient met the European Society of Cardiology Task Force criteria on the clinical diagnosis of myocarditis7 with an acute chest pain history, abnormal ECG, raised cardiac biomarkers, and LV systolic dysfunction on echocardiogram. However, he did not meet the Lake Louise Criteria (LLC) for myocarditis14 or demonstrate an abnormal elevation of T1 or T2 values on T1 and T2 mapping during CMR. We hypothesize that as the myocarditis driver was removed 2 weeks prior, this allowed resolution of the inflammation with a prompt return to baseline functioning as supported by the literature.9,11,12 This was possibly expedited by the concurrent steroid course he was prescribed for his colitis flare.13 Conversely, the time interval of 2 weeks following the acute myocarditis episode could also explain why LLC was negative.15

In our clinical case, the patient’s myocarditis symptomatology was secondary to mesalazine rather than active IBD; supported by the onset of symptoms within the first 2 weeks of drug commencement and rapid resolution of symptoms with recovery of cardiac function soon after discontinuing mesalazine. Despite this, EMB remains the gold standard practice for the diagnosis of myocarditis to confirm the underlying aetiology and characteristics of inflammation; which influences the treatment approach and prognosis.7 Despite being the gold standard practice, EMB remains largely underutilized in the real world.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be aware of the non-infectious causes of myocarditis that would influence management and lead to resolution like this case. This clinical report highlights the important and potentially life-threatening complication of 5-ASA therapy which should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis in patients who are on mesalazine presenting with chest pain or HF. Cessation of the drug should promptly follow, and other causes of myocarditis excluded. The mainstay of treatment remains to simply discontinue mesalazine, which leads to prompt and rapid recovery of symptoms and a return to baseline cardiac functioning. Close liaison with the gastroenterology team is required to ensure appropriate 2nd line therapy is initiated for the patient’s ongoing colitis management.

Lead author biography

Dr Simran Shergill graduated from the University of Birmingham in 2015. He completed his MRCP in 2018 and is currently working as a Cardiology Speciality Doctor at South Warwickshire NHS Foundation Trust.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The author confirms that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with the journal and COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor AL, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R. et al. ; on behalf of the IBD Section of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2011;60:571–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergman R, Parkes M.. Systematic review: the use of mesalazine in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:841–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loftus EV Jr, Kane SV, Bjorkman D.. Systematic review: short-term adverse effects of 5-aminosalicylic acid agents in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:179–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zakko SF, Gordon GL, Murthy U, Sedghi S, Pruitt R, Barrett AC. et al. Once-daily mesalamine granules for maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis: pooled analysis of efficacy, safety, and prognostic factors. Postgrad Med 2016;128:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown SR, Coviello LC.. Extraintestinal manifestations associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Surg Clin North Am 2015;95:1245–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorensen HT, Fonager KM.. Myocarditis and inflammatory bowel disease: a 16-year Danish nationwide cohort study. Dan Med Bull 1997;44:442–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caforio AL, Pankuweit S, Arbustini E, Basso C, Gimeno-Blanes J, Felix SB. et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management and therapy of myocarditis: a position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2636–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bunu DM, Timofte CE, Ciocoiu M, Floria M, Tarniceriu CC, Barboi OB. et al. Cardiovascular manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and preventive strategies. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2019;2019:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haq MI, Ahmed S, Pasha W, Zaidi SA.. Mesalazine-induced cardiotoxicity. J Rare Disord Diagn Ther 2019;4:24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss AC, Peppercorn MA.. The risks and the benefits of mesalazine as a treatment for ulcerative colitis. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2007;6:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown G. 5-Aminosalicyclic acid associated myocarditis and pericarditis: a narrative review. Can J Hosp Pharm 2016;69:466–472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Ye J, Zhu J, Chen W, Sun Y.. Myocarditis due to mesalamine treatment in a patient with Crohn’s disease in China. Turk J Gastroenterol 2012;23:304–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hinojar R, Foote L, Sangle S, Marber M, Mayr M, Carr-White G. et al. Native T1 and T2 mapping by CMR in lupus myocarditis: disease recognition and response to treatment. Int J Cardiol 2016;222:717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedrich MG, Sechtem U, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, Alakija P, Cooper LT. et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocarditis: A JACC White Paper. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1475–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Schüler J, Dogangüzel S, Dieringer MA, Rudolph A, Greiser A. et al. Detection and monitoring of acute myocarditis applying quantitative cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:e005242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.