Abstract

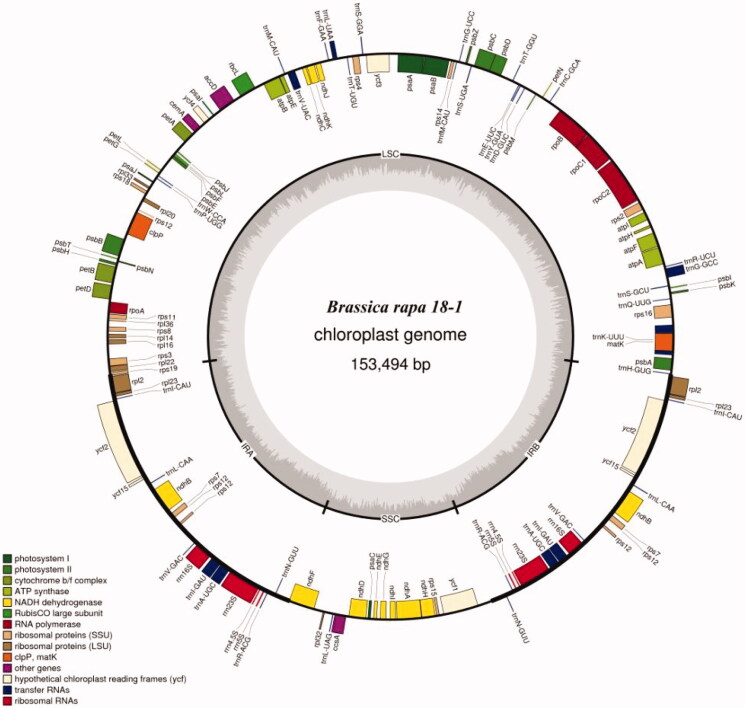

Winter oil rapeseed ‘18 R-1’ (Brassica rapa L.) is a new variety that can survive in northern China where the extreme low temperature is −20 °C to −32 °C. It is different from traditional B. rapa and Brassica napus. In this study, the complete chloroplast (cp) genome of ‘18 R-1’ was sequenced and analyzed to assess the genetic relationship. The size of cp genome is 153,494 bp, including one large single copy (LSC) region of 83,280 bp and one small single copy (SSC) region of 17,776 bp, separated by two inverted repeat (IR) regions of 26,219 bp. The GC content of the whole genome is 36.35%, while those of LSC, SSC, and IR are 34.12%, 29.20%, and 42.32%, respectively. The cp genome encodes 132 genes, including 87 protein-coding genes, eight rRNA genes, and 37 tRNA genes. In repeat structure analysis, 288 simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were identified. Cp genome of ‘18 R-1’ was closely related to Brassica chinensis, B. rapa and Brassica pekinesis.

Keywords: Winter oil rapeseed, chloroplast genome, SSRs, phylogeny

Introduction

Winter oil rapeseed (Brassica rapa L.) is a new cultivar used as oil crop in northern China. It can survive in fields where the extreme low temperature is −20 to −32 °C in winter. It makes northern China grow winter rapeseed now where is spring rapeseed zone before (Wancang et al. 2010; Dongmei et al. 2014). Growing winter rapeseed has many advantages in northern China. Firstly, winter rapeseed sows in mid-August, and turns green in late March next year, harvests in early June which is one and a half months earlier than spring crops. So after harvests, it is possible for a succeeding crop such as maize, potato, millet, corn, buckwheat, vegetables and others (Sun et al. 2016). It can make full use of heat and light of this area and change the traditional 1-year-one-ripe pattern to a 2-year-three ripe pattern (Wang et al. 2009). In this way, it can avoid spring farming in this area and result in increasing land cover during winter. So winter rapeseed is a cover crop in winter and it will reduce soil surface dust (Xuefang et al. 2009).

Chloroplast (cp) is common in plant and other organism. Because it is simple, conservative and rearranged, it is mainly used to analyze the origin and evolution of species (Szymon et al. 2016). In our research, we find that winter rapeseed (B. rapa) is different from B. napus and B. rapa cultivars. It has strong cold tolerance and low growing point. So in this study, we used a winter oil rapeseed variety, ‘18 R-1’ and constructed its whole cp genome. We compared the cp genome with other members of Brassica to make sure its genetic evolutionary relationship. It is expected that the results will provide a theoretical basis for the determination of phylogenetic status and future breeding research.

Materials and methods

Sampling, DNA extraction, sequencing, and assembly

The experiments were set up in Gansu Agricultural University, China (N. 36.05°, E. 103.87°). ‘18 R-1’ seeds were sowed in pot. Fresh leaves were collected at five-leaf-stage and were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately then stored at −80 °C until analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted by the modified method CTAB (Li et al. 2019). After testing qualified, genomic DNA samples were broken into fragments with the mechanical interrupt method (ultrasonic). Then fragment purification, terminal repair, the addition of 3’terminal A and connection of sequencing connector were performed for fragmented DNA. The fragment size was selected by agarose gel electrophoresis, and the sequencing library was formed by PCR amplification. The library was inspected first, then the qualified library shall be sequenced and sequencing reading length was PE150. Sequencing was performed with an Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform (Nanjing, China, N. 31.14°, E. 118.22°), yielding at least 11.02 GB of clean base. All of the raw reads were trimmed by Fastqc. The core module was assembled using SPAdes (Bankevich et al. 2012) software to assemble the chloroplast genome, independent of the reference genome.

Annotation and analysis of the cpDNA sequences

CpGAVAS was used to annotate the sequences. DOGMA (http://dogma.ccbb.utexas.edu/) and BLAST were used to check the results of the annotation (Liu et al. 2012; Wyman et al. 2004). The circular gene map of 18 R-1 was drawn using the OGDRAWv1.2 program (Lohse et al. 2007). An analysis of variation in synonymous codon usage, relative synonymous codon usage values (RSCU), codon usage, and GC content of the complete plastid genomes and commonly analyzed CDS was conducted. CpSSR analysis was performed using the MISA (Song et al. 2019).

Genome comparison

The mVISTA (Mayor et al. 2000) program was applied to compare the complete cp genome of ‘18 R-1’ to the other published cp genomes of its related species.

Phylogenetic analysis

It used genome-wide analysis by setting the same starting points for ring sequences. Multiple sequence alignment was performed with MAFFT software (v7.427, auto mode). Sequence alignment data were trimmed with trimAl (v1.4.rev15). Then using RAxML v8.2.10 software (https://cme.h-its.org/exelixis/software.html) and GTRGAMMA model, we built maximum likelihood evolutionary tree with rapid Bootstrap analysis (Bootstrap = 1000). Phylogenetic tree was constructed using 25 cp genome of the Cruciferae species sequences from the NCBI organelle genome and nucleotide resources database (Katoh et al. 2005; Lam-Tung et al. 2015; Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001; Xiayu et al. 2019).

Results and discussion

Cp genome size

The accession number of complete cp genome on Genebank is MT726210 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MT726210). The size of ‘18 R-1’ cp genome is 153,494 bp which has 132 genes including 37 tRNAs, eight rRNAs, and 87 mRNAs (Figure 1; Table 1). Most genes have only one copy, while 19 genes (ndhB, rpl2, rpl23, rps12, rps7, rrn16S, rrn23S, rrn4.5S, rrn5S, trnA-UGC, trnI-CAU, trnI-GAU, trnL-CAA, trnN-GUU, trnR-ACG, trnV-GAC, ycf1, ycf15, ycf2) with two copies. The cp genome displayed a typical quadripartite structure, including a pair of IR (IRA and IRB, 26,219 bp) separated by the large single copy (LSC; 83,280 bp) and small single copy (SSC; 17,776 bp) regions (Figure 1). The DNA GC contents of LSC, SSC, IR, and the whole genome are 34.12%, 29.20%, 42.32%, and 36.35%, respectively. It is obvious that GC content of the IR region is higher than that of other regions. This phenomenon is very common in other plants (Nguyen et al. 2015). GC skewness has been shown to be an indicator of DNA lead chains, lag chains, replication origin, and replication terminals (Dan et al. 2019; Yan et al. 2018).

Figure 1.

Cp genome map of 18 R-1. Genes inside the circle are transcribed clockwise, and those outside are transcribed counterclockwise. Genes of different functions are color-coded. The darker gray in the inner circle shows the G + C content, while the lighter gray shows the A + T content.

Table 1.

List of genes annotated in the cp genomes of winter rapeseed.

| Function | Genes |

|---|---|

| RNAs, transfer | trnH-GUG, trnS-GCU, trnG-GCCa, trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnY-GUA, trnT-GGU, trnF-GAA, trnS-GGA, trnI-GAUa, trnN-GUU, trnV-GAC, trnG-UCC, trnE-UUC, trnK-UUUa, trnQ-UUG, trnR-UCU, trnS-UGA, trnT-UGU, trnL-UAAa, trnS-UAG, trnV-UACa, trnL-UAG, trnA-UGCa, trnA-UCG, trnP-UGG, trnfM-CAU, trnM-CAU, trnI-CAU, trnW-CCA, trnA-CGU, trnL-CAA, trnL-CAA, trnR-ACG |

| RNAs, ribosomal | rrn16, rrn23, rrn4.5, rrn5 |

| Transcription and splicing | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1a, rpoC2 |

| Translation, ribosomal proteins | rps12b, rpl36, rpl32 |

| Small subunit | rps2, rps4, rps14, rps133, rps18, rps11, rps8, rps3, rps7, rps15 |

| Large subunit | rpl20, rpl12, rpl14, rpl16, rpl22, rps19, rpl2a, rpl23 |

| ATP synthase | atpA, atpFa, atpH, atpI, atpB, atpE, |

| Photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ, ycf1, ycf3b, ycf4 |

| Photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psdC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbZ, psbT |

| Calvin cycle | rbcL |

| Cytochrome complex | petA, petL, petBa, petDa, ccsA |

| NADH dehydrogenase | ndhJ, ndhK, ndhC, ndhBa, ndhF, ndhE, ndhG, ndhAa, ndhH, ndhD |

| Others | cemA, clpP, clpPb, ycf2, ycf15a, accD |

aGenes containing one intron; bGenes containing two introns.

Seventeen intron-containing genes were found in the cp genome including 12 genes with 1 intron and 3 genes with 2 introns (Table 1). Introns also vary in size. The trnK-UUU has longest intron (2561 bp) and trnL-UAA has the shortest (313 bp).

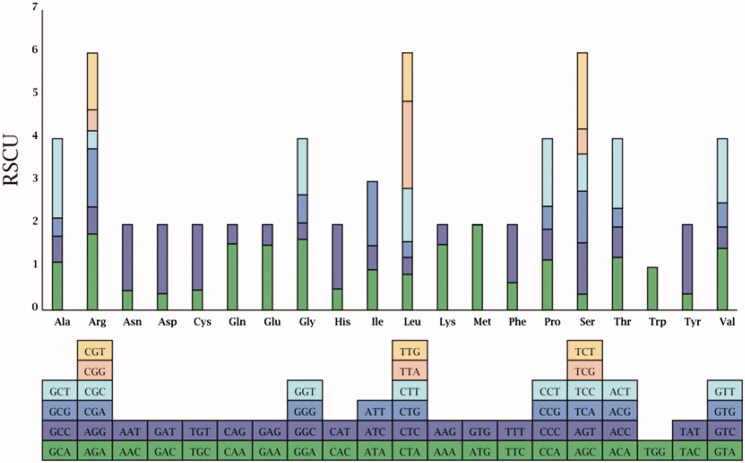

RSCU analysis

RSCU is relative synonymous codon usage. Because of the degeneracy of codons, each amino acid corresponds to at least 1 codon and at most 6 codons. The utilization rate of genomic codon varies greatly among different species and organisms. RSCU is thought to be the result of natural selection, mutation and genetic drift.

Regardless of termination codon, UUA encoding ‘Leu’ was the most used codon, while GUG encoding ‘Met’ was the fewest used codon (Table 2; Figure 2). There are 30 codons with RSCU greater than 1, in which the third base are all ending in A/U. It indicated that winter rapeseed preferred to use the codon ending in A/U in the third base. There is only one codon, UGG, which RSCU is 1.

Table 2.

Codon preference analysis statistics.

| Amino acid | Symbol | Codon | No. | RSCU |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * | Ter | UAA | 52 | 1.7931 |

| Ter | UAG | 23 | 0.7932 | |

| Ter | UGA | 12 | 0.4137 | |

| A | Ala | GCA | 381 | 1.1232 |

| Ala | GCC | 205 | 0.6044 | |

| Ala | GCG | 143 | 0.4216 | |

| Ala | GCU | 628 | 1.8512 | |

| C | Cys | UGC | 74 | 0.4684 |

| Cys | UGU | 242 | 1.5316 | |

| D | Asp | GAC | 197 | 0.3870 |

| Asp | GAU | 821 | 1.6130 | |

| E | Glu | GAA | 1014 | 1.5146 |

| Glu | GAG | 325 | 0.4854 | |

| F | Phe | UUC | 498 | 0.6422 |

| Phe | UUU | 1053 | 1.3578 | |

| G | Gly | GGA | 718 | 1.6524 |

| Gly | GGC | 167 | 0.3844 | |

| Gly | GGG | 285 | 0.6560 | |

| Gly | GGU | 568 | 1.3072 | |

| H | His | CAC | 146 | 0.4940 |

| His | CAU | 445 | 1.5060 | |

| I | Ile | AUA | 702 | 0.9435 |

| Ile | AUC | 419 | 0.5631 | |

| Ile | AUU | 1111 | 1.4934 | |

| S | Ser | AGC | 125 | 0.3750 |

| Ser | AGU | 399 | 1.1964 | |

| Ser | UCA | 402 | 1.2054 | |

| Ser | UCC | 289 | 0.8664 | |

| Ser | UCG | 194 | 0.5820 | |

| Ser | UCU | 592 | 1.7754 | |

| M | Met | AUG | 588 | 1.9898 |

| Met | GUG | 3 | 0.0102 | |

| T | Thr | ACA | 411 | 1.2304 |

| Thr | ACC | 237 | 0.7096 | |

| Thr | ACG | 146 | 0.4372 | |

| Thr | ACU | 542 | 1.6228 | |

| K | Lys | AAA | 1110 | 1.5290 |

| Lys | AAG | 342 | 0.4710 | |

| L | Leu | CUA | 386 | 0.8364 |

| Leu | CUC | 183 | 0.3966 | |

| Leu | CUG | 168 | 0.3636 | |

| Leu | CUU | 573 | 1.2414 | |

| Leu | UUA | 939 | 2.0340 | |

| Leu | UUG | 521 | 1.1286 | |

| N | Asn | AAC | 290 | 0.4574 |

| Asn | AAU | 978 | 1.5426 | |

| P | Pro | CCA | 306 | 1.1712 |

| Pro | CCC | 188 | 0.7196 | |

| Pro | CCG | 140 | 0.5360 | |

| Pro | CCU | 411 | 1.5732 | |

| Q | Gln | CAA | 713 | 1.5450 |

| Gln | CAG | 210 | 0.4550 | |

| R | Arg | AGA | 454 | 1.7790 |

| Arg | AGG | 160 | 0.6270 | |

| Arg | CGA | 346 | 1.3560 | |

| Arg | CGC | 108 | 0.4230 | |

| Arg | CGG | 124 | 0.4860 | |

| Arg | CGU | 339 | 1.3284 | |

| V | Val | GUA | 501 | 1.4408 |

| Val | GUC | 174 | 0.5004 | |

| Val | GUG | 196 | 0.5636 | |

| Val | GUU | 520 | 1.4952 | |

| W | Trp | UGG | 441 | 1.0000 |

| Y | Tyr | UAC | 182 | 0.3816 |

| Tyr | UAU | 772 | 1.6184 |

Note: ‘*’ means stop codon.

Figure 2.

RSCU distribution.

Repeat sequence and SSR analysis

By the REPuter analysis, there are 37 repeat sequences in the cp genome (Table 3). Except for one repeat with the length of 26,219 bp, the others are 30 bp to 58 bp. Most of the repeats are located in LSC region. Palindrome repeats are 18 while forward repeats are 14, and reverse and complement repeats are 3 and 2, respectively.

Table 3.

Repetitive sequences identified in the cp genome.

| No. | Size (bp) | Type | Repeat I start | Gene | Region | Repeat II start | Gene | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 | F | 47,009 | trnF-GAA | LSC | 47,063 | trnF-GAA | LSC |

| 2 | 46 | F | 37,864 | psaB | LSC | 40,088 | psaA | LSC |

| 3 | 45 | P | 75,812 | petD | LSC | 75,812 | petD | LSC |

| 4 | 44 | P | 73,309 | IGS | LSC | 73,309 | IGS | LSC |

| 5 | 43 | F | 37,843 | psaB | LSC | 40,067 | psaA | LSC |

| 6 | 42 | F | 27,344 | IGS | LSC | 27,364 | IGS | LSC |

| 7 | 40 | P | 28,246 | IGS | LSC | 28,246 | IGS | LSC |

| 8 | 37 | F | 97,927 | IGS | IRb | 119,493 | ndhA | SSC |

| 9 | 37 | P | 119,493 | ndhA | SSC | 138,810 | IGS | IRa |

| 10 | 37 | C | 7944 | IGS | LSC | 35,443 | IGS | LSC |

| 11 | 36 | P | 9237 | IGS | LSC | 9237 | IGS | LSC |

| 12 | 35 | R | 4588 | IGS | LSC | 4588 | IGS | LSC |

| 13 | 34 | F | 106,834 | IGS | IRb | 106,866 | IGS | IRb |

| 14 | 34 | P | 106,834 | IGS | IRb | 129,874 | IGS | IRa |

| 15 | 34 | P | 106,866 | IGS | IRb | 129,906 | IGS | IRa |

| 16 | 34 | F | 129,874 | IGS | IRa | 129,906 | IGS | IRa |

| 17 | 33 | P | 172 | IGS | LSC | 175 | IGS | LSC |

| 18 | 32 | F | 7949 | IGS | LSC | 35,447 | IGS | LSC |

| 19 | 32 | F | 88,213 | ycf2 | IRb | 88,234 | ycf2 | IRb |

| 20 | 32 | P | 88,213 | ycf2 | IRb | 148,508 | ycf2 | IRa |

| 21 | 32 | P | 88,234 | ycf2 | IRb | 148,529 | ycf2 | IRa |

| 22 | 32 | F | 148,508 | ycf2 | IRa | 148,529 | ycf2 | IRa |

| 23 | 31 | F | 7635 | trnS-GCU; | LSC | 34,497 | trnS-UGA | LSC |

| 24 | 31 | R | 172 | IGS | LSC | 34,592 | trnS-UGA | LSC |

| 25 | 31 | R | 12,208 | atpF | LSC | 75,812 | petD | LSC |

| 26 | 30 | F | 47,037 | trnF-GAA | LSC | 47,091 | IGS | LSC |

| 27 | 30 | P | 7636 | trnS-GCU | LSC | 44,059 | trnS-GGA | LSC |

| 28 | 30 | F | 42,956 | ycf3 | LSC | 97,936 | IGS | IRb |

| 29 | 30 | P | 42,956 | ycf3 | LSC | 138,808 | IGS | IRa |

| 30 | 30 | P | 61,677 | IGS | LSC | 61,677 | IGS | LSC |

| 31 | 30 | P | 64,761 | IGS | LSC | 64,761 | IGS | LSC |

| 32 | 30 | P | 122,764 | IGS | SSC | 123,309 | ycf1 | SSC |

| 33 | 30 | F | 3758 | trnK-UUU | LSC | 6274 | IGS | LSC |

| 34 | 30 | P | 34,498 | trnS-UGA | LSC | 44,059 | trnS-GGA | LSC |

| 35 | 30 | P | 34,566 | trnS-UGA | LSC | 43,997 | trnS-GGA | LSC |

| 36 | 30 | C | 7937 | IGS | LSC | 35,447 | IGS | LSC |

| 37 | 26,219 | P | 83,280 | IR | 127,275 | IR |

Note: F: forward; P: palindromic; R: reverse; C: complement; IGS: intergenic region.

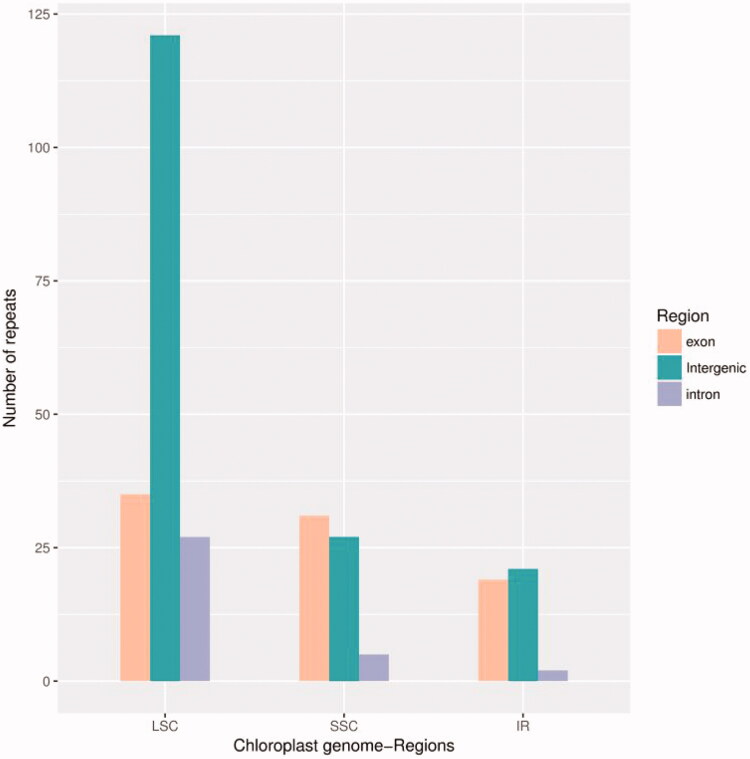

The cp genome has 288 SSRs, including 228 mononucleotide repeats which are mainly A and T, 17 dinucleotide repeats, 63 trinucleotide repeats and 6 tetranucleotide repeats (Figure 3). From the location of SSR distribution, the vast majority (63.50%) is located in LSC region, and 21.90% located in SSC region and 14.60% in IR region (Figure 4). The SSRs of tandem guanine (G) and cytosine (C) is fewer which means it has strong A and T bias. Most SSRs are distributed in intergenomic region, followed by exon region, and intron region was the least. These repeated sequences can be applied to the development of molecular markers and provide guidance for the evolutionary study of winter rapeseed.

Figure 3.

Length of repeat (bp) and repeated sequence.

Figure 4.

SSR sequences of cp genome.

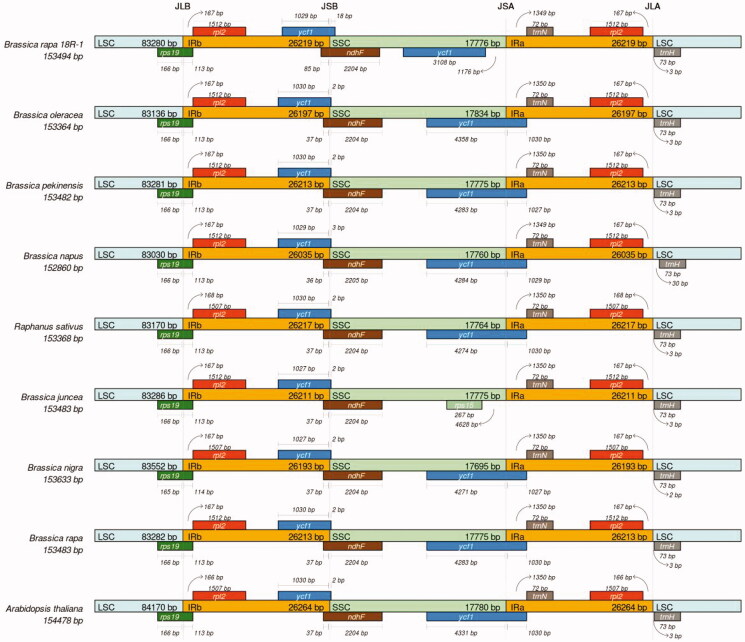

IR scope analysis

Cp genomes of other eight Cruciferous species were selected for comparative analysis of LSC/IRs and SSC/IRs boundaries with 18 R-1. The LSC/IRb boundary of 9 species located in the coding region of rps19, which spans two regions and is 166 bp at LSC region while 113 bp at IRb region. It is reported that LSC/IRb boundary is stable in many species (Zhao et al. 2019). In most species, IRb/SSC boundary lies in the overlap region between ycf1 gene and ndhF gene (Zhao et al. 2019). In 9 Cruciferous species the IRb/SSC boundary is ycf1 and ndhF too. At SSC/IRa boundary, ycf1 straddles the edge in seven species. There is no ycf1 in Brassica juncea. It is also special in ‘18 R-1’ that ycf1 is shorter than others and 17,776 bp far from the edge. Near the edge of IRa/LSC, it is rpl2 in IRa region and trnH in LSC region ranging from 2 bp to 30 bp from boundary (Shi et al. 2020). In some plants, trnH is also common in IR region and rpl22 gene straddles the IRa/LSC boundary (Dan et al. 2019) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Analysis of cp IR scope change.

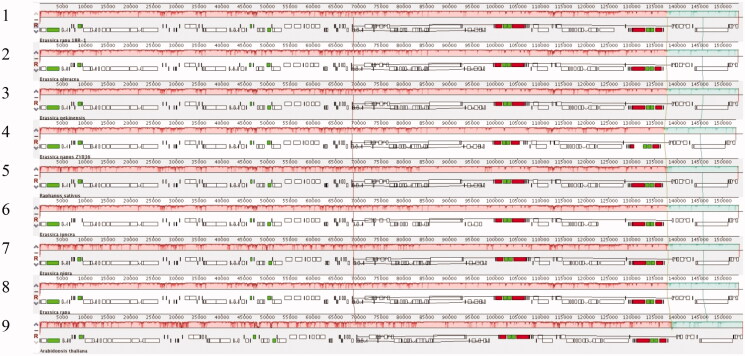

Cp genome sequence homology analysis

Using mVISTA online software we assessed the difference of ‘18 R-1’ and other nine Brassica species. The results showed that sequences of nine species were highly similar. There was also little variation in the length of each region. Collinearity analysis showed that the cpDNA sequences of nine species did not detect large fragments of gene rearrangement, indicating that the cpDNA sequences were relatively conservative (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Synteny analysis of chloroplast genomes from nine species in Cruciferae. 1. 18R-1; 2. Brassica loerance; 3. Brassica pekinesis; 4. Brassica napus; 5. Raphanus sativus; 6. Brassica juncea; 7. Brassica nigra; 8. Brassica rapa; 9. Arabidopsis thaliana.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was based on the complete cp genome from 14 Cruciferae species (Figure 6). Almost all confidence factors of branches are high (93–100) except for branch between ‘Brassica rapa’ and ‘Brassica pekinesis’. The higher is the branch’s confidence factor, the more consistent is the guiding value of the evolutionary analysis for the relationship. Capsella Rubella and Camelina sativa are early differentiated groups. ‘18 R-1’ is a late group. It gathers together with Brassica chinensis first, then with B. rapa and Brassica pekinensis. It means cp genome of ‘18 R-1’ was closely related to Brassica chinensis. Brassica rapa and Brassica pekinesis are located at the innermost of the branch which infers to they are probably the last group of Brassica to be differentiated (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree constructed from the maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference based on the complete chloroplast genomes. Note: Numbers near each branch is confidence factors in BI.

Conclusions

In this study, we reported and analyzed the complete cp genome of a new cultivar ‘18 R-1’ (B. rapa), a winter oil rapeseed in China. The cp genome was shown to be more conservative with similar characteristics to other Brassica species. An analysis of the phylogenetic relationships among nine species found ‘18 R-1’ was closely related to B. chinensis. We can infer that it is different from B. rapa. This may be because ‘18-R’ is an oil crop and the cp genome data for B. rapa published are from vegetable crops. The results of this study provide an assembly of a whole chloroplast genome of B. rapa used as oil crops which might facilitate genetics, breeding, and biological discoveries in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiaolong Luo (Genepioneer Biotechnologies, Nanjing 210014, China) for the assistance in bioinformatics analysis.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BI

Bayesian inference

- C

Cytosine

- cp

Chloroplast

- CpSSR

Chloroplast Simple sequence repeats

- G

Guanine

- IR

Inverted repeat

- LSC

Large single copy

- NCBI

National center for biotechnology information

- RSCU

Relative synonymous codon usage values

- SSC

Small single copy

- SSRs

Simple sequence repeats

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the China Agriculture Research System [CARS-12] and the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province [17JR5RA149].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The accession number on Genebank is MT726210 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MT726210).

References

- Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D.. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 19(5): 455–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan Z, Anpei Z, Yao Z, Xinlian Z, Dan L, Anan D, Chengzhong H.. 2019. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genomes of five Populus species from the western Sichuan plateau, southwest China: comparative and phylogenetic analyses. Peer J. 7:e6386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongmei Z, Renzhi Z, Wancang S, Jun Z, Heling W.. 2014. Evaluation of the suitability and influencing factors of winter rapeseed planting in Gansu Province. Chin J Ecoagric. 22:697–704. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F.. 2001. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 17(8):754–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T.. 2005. MAFFT version 5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 33(2):511–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam-Tung N, Schmidt HA, Arndt VH, Quang MB.. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 32(1):268–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Coulter Jeffrey A, Lijun L, Yuhong Z, Yu C, Yuanyuan P, Xiucun Z, Yaozhao X, Junyan W, Yan F, et al. 2019. Transcriptome analysis reveals key cold-stress-responsive genes in winter rapeseed (Brassica rapa L.). IJMS. 20(5):1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Shi L, Zhu Y, Chen H, Zhang J, Lin X, Guan X.. 2012. CpGAVAS, an integrated web server for the annotation, visualization, analysis, and GenBank submission of completely sequenced chloroplast genome sequences. BMC Genomics. 13:715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohse M, Drechsel O, Bock R.. 2007. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW): a tool for the easy generation of high-quality custom graphical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Curr Genet. 52(5–6):267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor C, Brudno M, Schwartz JR, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Frazer KA, Pachter LS, Dubchak I.. 2000. VISTA: visualizing global DNA sequence alignments of arbitrary length. Bioinformatics. 16(11):1046–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PAT, Kim JS, Kim JH.. 2015. The complete chloroplast genome of colchicine plants (Colchicum autumnale L. and Gloriosa superba L.) and its application for identifying the genus. Planta. 242(1):223–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C, Han K, Li L, Seim I, Ming-Yuen Lee S, Xu X, Yang H, Fan G, Liu X.. 2020. Complete chloroplast genomes of 14 mangroves: phylogenetic and comparative genomic analyses. BioMed Res Int. 13:8731857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Ting S, Wenjie L, Xiaopeng NS, IqbalZhaojun N, Xiao H, Dan Y, Zhijun S, Zhihong G.. 2019. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome among Prunus mume, P. armeniaca, and P. salicina. Hortic Res. 6:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W-C, Liu H-Q, Liu Z-G, Wu J-Y, Li X-C, Fang Y, Zeng X-C, Xu Y-Z, Zhang Y-H, Dong Y.. 2016. Critical index analysis of safe over-wintering rate of winter rapeseed (Brassica rapa) in cold and arid region in North China. Acta Agron Sin. 42(4):609–618. [Google Scholar]

- Szymon AO, Ewelina Ł, Tomasz K, Tomasz S.. 2016. Chloroplasts: state of research and practical applications of plastome sequencing. Planta. 244:517–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wancang S, Junyan W, Yan F, Qin L, Renyi Y, Weiguo M, Xuocai L, Junjie Z, Pengfei Z, Jianming C, Jia , et al. 2010. Growth and development characteristics of winter rapeseed northern-extended from the cold and arid regions in China. Acta Agron Sin. 36:2124–2134. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X-F, Sun W-C, Li X-Z, Wu J-Y, Ma W-G, Kang Y-L, Zeng C-W, Pu Y-Y, Ye J, Liu H-X, et al. 2009. Effects of environment on winter rapeseed in Hexi corridor. A A S. 34(12):2210–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL.. 2004. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 20(17):3252–3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiayu G, Qinghua Y, Zekun L, Chengle Z, Qingxi C.. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of a variety of Epipremnum aureum 'Neon' (Araceae). Mitochondrial DNA B. 4(1):781–782. No [Google Scholar]

- Xuefang W, Wancang S, Xiaoze L, Junyan W, Hongxia L, Chaowu Z, Yuanyuan P, Pengfei Z, Junjie Z.. 2009. Wind erosion-resistance of fields planted with winter rapeseed in the wind erosion region of Northern China. Acta Ecol Sin. 29(12):6572–6577. [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Zhirong Z, Junbo Y, Guanghui L.. 2018. Complete chloroplast genome of seven Fritillaria species, variable DNA markers identification and phylogenetic relationships within the genus. PloS One. 13(3):e0194613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Yang Z, Zhao Y, Li X, Zhao Z, Zhao G.. 2019. Chloroplast genome structural characteristics and phylogenetic relationships of Oleaceae. Chin Bull Bot. 54(4):441–454. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The accession number on Genebank is MT726210 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MT726210).