Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Key Words: telehealth, COVID-19, mental health

Abstract

Background:

Since coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused dramatic changes in everyday life, a major concern is whether patients have adequate access to mental health care despite shelter-in-place ordinances, school closures, and social distancing practices.

Objectives:

The aim was to examine the availability of telehealth services at outpatient mental health treatment facilities in the United States at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and to identify facility-level characteristics and state-level policies associated with the availability.

Research Design:

Observational cross-sectional study.

Subjects:

All outpatient mental health treatment facilities (N=8860) listed in the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration on April 16, 2020.

Measures:

Primary outcome is whether an outpatient mental health treatment facility reported offering telehealth services.

Results:

Approximately 43% of outpatient mental health facilities in the United States reported telehealth availability at the outset of the pandemic. Facilities located in the United States South and nonmetropolitan counties were more likely to offer services, as were facilities with public sector ownership, those providing care for both children and adults, and those accepting Medicaid as a form of payment. Outpatient mental health treatment facilities located in states with state-wide shelter-in-place laws were less likely to offer telehealth, as well as facilities in counties with more COVID-19 cases per 10,000 population.

Conclusions:

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer than half of outpatient mental health treatment facilities were providing telehealth services. Our results suggest that additional policies to promote telehealth may be warranted to increase availability over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since the outset of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States, access to outpatient mental health services has undergone a dramatic transformation. Mental health systems have been constrained by federal guidance and state ordinances requesting that health facilities limit in-person consultations,1 at a time when social isolation resulting from social distancing practices, as well as psychological distress concerning possible COVID-19 exposure,2 have placed further strain on mental health care services.3–6

To limit in-person contact in situations where services can be provided at home, outpatient providers are rapidly pivoting to telehealth—both in audio-based and video-based clinical visits. This transition has been supported by new Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services’ (CMS) reimbursement codes for telehealth services, which includes mental health counseling, preventive health screenings, and services provided by clinical psychologists and licensed clinical social workers.7 CMS is also temporarily allowing practitioners licensed out-of-state who meet certain requirements to provide services in states in which they are unlicensed.8 In addition, the Department of Health and Human Services’ has broadened telehealth enforcement discretion, allowing health care providers to have audio or video communications that are not in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act rules as long as they are acting in good faith.9

The extent to which outpatient mental health care facilities are equipped for this transition to provide telehealth services likely varies as a function of both existing telehealth infrastructure and facility characteristics. For instance, the number of telehealth visits increased rapidly for rural Medicare advantage beneficiaries between 2004 and 2014.10 Over the past several years, Federally Qualified Health Centers that offer mental health services have also received subsidies to increase telehealth capacity through mechanisms such as Health Resources and Services Administration grants.11

To date, there has been little examination of the telehealth infrastructure at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, one recent study focused on availability of telehealth services in hospital settings in 2018.12 Our study provides an important and timely snapshot of national telehealth availability at outpatient mental health treatment facilities at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, which was declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020.13 We also assess facility and state characteristics associated with the telehealth availability.

METHODS

Data and Sample

We obtained data on outpatient mental health treatment facilities (n=8860) from the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) on April 16, 2020.14 The data are based on the National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS) of 2019 (response rate=91%). In the N-MHSS the facility was asked: “If eligible, does this facility want to be listed in SAMHSA’s online Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator and Mental Health Directory?” Facilities that answered yes were listed in the locator data. In addition, SAMHSA claims that new facilities are validated and included monthly, and that updates on facility information are made weekly for facilities informing SAMSA of changes.14 The types of facilities that are surveyed by SAMHSA for the N-MHSS include psychiatric hospitals, general hospitals with a separate inpatient psychiatric unit, Veteran Administration (VA) medical centers, partial hospitalization/day treatment mental health facilities, outpatient mental health facilities, residential treatment center for children, residential treatment centers for adults, multisetting mental health facilities, community mental health centers, and other types of residential treatment facilities.

Our analysis focused on outpatient menta health treatment facilities as they are reportedly converting many of their in-person visits to telehealth visits to decrease the risk of transmitting the virus to patients or health care workers.15

Analytic Strategy

Both descriptive analyses and a multivariable logistic regression were run to assess the relationships between telehealth service availability and facility characteristics likely to influence telehealth capacity—including region, county metropolitan status, acceptance of Medicaid as payment, facility ownership, and populations served (children and adults vs. adults only). Standard errors in the logistic regression were clustered at the state-level.

To better understand the implementation context, we included three state-level characteristics: telemedicine parity laws, American Telemedicine Association state telemedicine performance grade, and existence of COVID-19 stay-at-home or shelter-in-place ordinance as of April 8, 2020.16 Finally, to understand the availability of telehealth services in relation to pandemic exposure we included data on the number of COVID-19 cases per 10,000 residents at the county-level as of April 16, 2020.17 We also estimated a separate model by excluding the VA medical centers, which operate differently from other mental health facilities. All analyses were conducted in April 2020, using Stata version 15.0.18 Our study was approved by the lead author’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Among the 8860 outpatient mental health treatment facilities, 3848 (43.4%) offered telehealth services (Table 1). Controlling for other factors, regression adjusted means indicate that telehealth services were more prevalent in the South (53.7%), West (47.8%), and Midwest (40.6%) compared with Northeast (26.8%, P<0.001), and in nonmetropolitan (53.2%) compared with metropolitan counties (40.3%, P<0.001). Facilities with public sector ownership (59.4%) versus not-profit (41.0%) or for-profit (36.2%) private facilities, facilities providing care to children and adults (45.2%) versus adults only (38.2%, P<0.001), and facilities not accepting Medicaid (54.0%) were also more likely to provide telehealth services (P<0.001). As the county-level number of COVID-19 cases per 10,000 population increased from the lowest quartile to the highest quartile, the share of facilities offering telehealth fell from 52.2% to 39.1% (P<0.001). The difference between the lowest and the third quartile of COVID-19 cases per 10,000 was also statistically significant (52.2% vs. 44.6%, P=0.015).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of Outpatient Mental Health Treatment Facilities Offering Telehealth Services

| Telehealth Services Available (Unadjusted) | Telehealth Services Available (Adjusted) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Mental Health Facilities | n (%) | P | % | P |

| The entire United States | 8860 | 3848 (43.4) | NA | NA | NA |

| US Region | |||||

| Northeast | 1889 | 397 (21.0) | Reference | 26.8 | Reference |

| Midwest | 2326 | 998 (42.9) | <0.001 | 40.6 | <0.001 |

| South | 2602 | 1447 (55.6) | <0.001 | 53.7 | <0.001 |

| West | 2043 | 2043 (49.2) | <0.001 | 47.8 | <0.001 |

| Metropolitan location | |||||

| Metropolitan | 6745 | 2517 (37.3) | Reference | 40.3 | Reference |

| Not metropolitan | 2115 | 1331 (62.9) | <0.001 | 53.2 | <0.001 |

| Form of payment | |||||

| Does not accept Medicaid | 936 | 500 (53.4) | Reference | 54.0 | Reference |

| Accepts Medicaid | 7924 | 3348 (42.3) | <0.001 | 42.1 | <0.001 |

| Patient population | |||||

| Serves children (no age limit or 10+) | 6617 | 2971 (44.9) | Reference | 45.2 | Reference |

| Serves adults only (17+) | 2243 | 877 (39.1) | <0.001 | 38.2 | <0.001 |

| Facility ownership | |||||

| Public sector | 1648 | 1028 (62.4) | Reference | 59.4 | Reference |

| Private for profit organization | 1790 | 655 (36.6) | <0.001 | 36.2 | <0.001 |

| Private nonprofit organization | 5422 | 2165 (39.9) | <0.001 | 41.0 | <0.001 |

| Community Mental Health Center | |||||

| No | 6452 | 2499 (38.7) | Reference | 41.2 | Reference |

| Yes | 2408 | 1349 (56.0) | <0.001 | 49.3 | <0.001 |

| Shelter-in-place law | |||||

| No state or local law | 426 | 257 (60.3) | Reference | 51.7 | Reference |

| Full state law | 8105 | 3409 (42.1) | <0.001 | 42.8 | 0.024 |

| Local not state law | 329 | 182 (55.3) | 0.167 | 48.3 | 0.575 |

| American Telemedicine Association Grade for State (2016) | |||||

| Grade A | 1044 | 535 (51.2) | Reference | 40.0 | Reference |

| Grade B | 6289 | 2694 (42.8) | <0.001 | 44.6 | 0.266 |

| Grade C | 1527 | 619 (40.5) | <0.001 | 40.9 | 0.845 |

| Telemedicine Parity Law (2016) | |||||

| No | 3623 | 1451 (40.0) | Reference | 42.9 | Reference |

| Yes | 5237 | 2397 (45.8) | <0.001 | 43.8 | 0.698 |

| COVID-19 cases | |||||

| First quartile (lowest) | 728 | 472 (64.8) | Reference | 52.2 | Reference |

| Second quartile | 1352 | 772 (57.1) | <0.001 | 49.8 | 0.296 |

| Third quartile | 2407 | 1120 (46.5) | <0.001 | 44.6 | 0.015 |

| Fourth quartile (highest) | 4373 | 1484 (33.9) | <0.001 | 39.1 | <0.001 |

The American Telemedicine Association grades are from the organization’s categorization of state telehealth policies based on 13 indicators that are related to coverage and reimbursement for telehealth services. More details on how the measures are created can be found here: https://mtelehealth.com/state-telemedicine-gaps-analysis-coverage-reimbursement/. The number of COVID-19 cases adjusted for population size comes from the USAFacts. After estimating the logistic regression, predictive margins were used to generate adjusted probabilities. Standard errors in the multivariable regression were clustered at the state level.

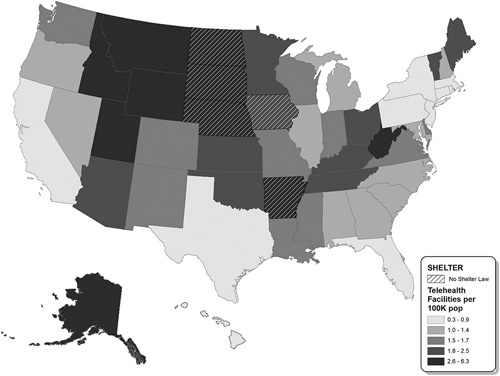

Availability of telehealth did not differ according to state telemedicine parity laws or telemedicine performance scores, adjusted for other factors. However, as shown in Figure 1, facilities within states that had COVID-19 shelter-in-place or stay-at-home ordinance for the entire state had fewer outpatient treatment facilities that offer telehealth services per capita than states without these ordinances (P=0.024).

FIGURE 1.

Map shows the number of outpatient mental health treatment facilities at the state-level that provide telehealth services per 100,000 population. State shelter-in-place laws come from New York Times, April 16th, 2020.

We found that almost all the VA medical centers offered telehealth (94%). Most of the regression results remained similar once we excluded the VA medical centers from our model, although the difference by whether the facility accepts Medicaid became statistically insignificant (Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/C173).

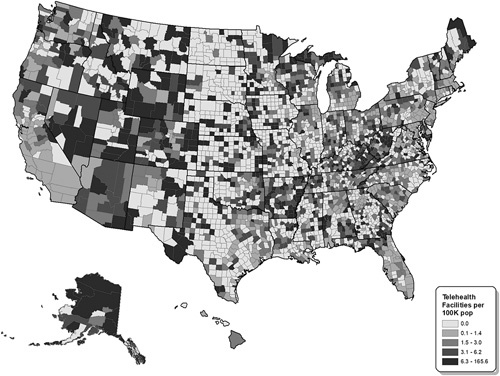

Figure 2 provides a detailed county-level map of outpatient mental health treatment facilities that provide telehealth throughout the United States. We use this map to illustrate the existing telehealth infrastructure at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. It shows that 20.3 million (6.5%) individuals in 415 (18.9%) counties did not have an outpatient mental health treatment facility that offered telehealth as of April 2020. The heat map indicates that, while fewer than half of outpatient mental health treatment facilities offer telehealth, those facilities are concentrated in the most populous counties. The share of counties with an outpatient mental health treatment facility that offers telehealth increases monotonically by the quartile of population density that the county belongs to. Only 35.3% of the least population dense counties (lowest quartile) had an outpatient treatment facility that offers telehealth services. In contrast, 83.8% of the most population dense counties (highest quartile) had an outpatient treatment facility that offers telehealth services. For comparison we reported the density of outpatient facilities offering telehealth services (Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/MLR/C173).

FIGURE 2.

Map shows the number of outpatient mental health treatment facilities at the county-level that provide telehealth services per 100,000 population.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to assess telehealth service availability among outpatient mental health treatment facilities in the United States at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This snapshot reveals limited telehealth infrastructure at outpatient mental health treatment facilities early in the pandemic, with only 43% of outpatient mental health treatment facilities reporting offering telehealth services. Telehealth availability varies from over 50% of facilities in the South and the West, to 21% in the Northeast. Together, the nation’s limited telehealth capacity and geographic variation may complicate efforts to meet the expected increase in demand for mental health care during the pandemic.

It is also concerning that fewer outpatient mental health facilities provide telehealth services in states with shelter-in-place or stay-at-home ordinances compared with states without these ordinances, as these ordinances may further limit access to in-person mental health care. States with shelter-in-place or stay-at-home ordinances are less rural and less likely to need telehealth services before the pandemic. Since the states with the ordinances were hit hard at the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, it will be interesting for future studies to examine whether telehealth services become more available in the states as the pandemic evolves. Similarly, we found that counties with a higher COVID-19 case rate as of April 16, 2020 were less likely to have an outpatient mental health facility that offers telehealth services. Policymakers and funders should consider efforts to rapidly support the implementation of telehealth services in those locations. By contrast, we also find that facilities that provide care to children—that is, those that are not restricted to adults—are more likely to offer telehealth services. This finding is somewhat promising, as children deprived of school-based mental health supports in the wake of school closures represent a particularly vulnerable population.4 However, even among facilities providing mental health care for children, only 45% reported offering telehealth services.

This study is not without limitations. First, not all outpatient mental health treatment facilities are in SAMHSA’s behavioral locator data. Data are limited to mental health treatment facilities that chose to be listed. Currently, there are no estimates for the share of mental health treatment facilities that chose not to be listed in the behavioral locator data. Approximately 9.3% of eligible facilities did not respond to the 2019 N-MHSS.19 It is not known how these facilities differ from those that took the survey. Second, the behavioral locator data do not contain information on treatment capacity or quality, so we do not know how many patients that facilities with telehealth capacity can treat virtually, nor the quality of care. Third, the data did not reflect changes in telehealth services after the national emergency declared on March 13, 2020. Future research can use our study findings as a benchmark to examine how telehealth services among mental health treatment facilities have increase after the national emergency. Fourth, the behavioral locator data did differentiate between telephone care and video-conference care. We believe that this is an important area of future research given that policy changes were made during the COVID-19 pandemic for equal reimbursement of video and audio telehealth services.20

In summary, our study found that, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer than half of outpatient mental health treatment facilities were providing telehealth services. There are substantial geographic disparities in the provision of telehealth. States with shelter-in-place or stay-at-home laws had fewer outpatient mental health treatment facilities that provided telehealth, and these locations may be less equipped to provide behavioral health care services. Our results suggest that additional policies to promote telehealth may be warranted to increase availability.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.

Footnotes

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Award No. R01MH112760).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Jonathan H. Cantor, Email: jcantor@rand.org.

Ryan K. McBain, Email: rmcbain@rand.org.

Aaron Kofner, Email: kofner@rand.org.

Bradley D. Stein, Email: stein@rand.org.

Hao Yu, Email: Hao_Yu@hphci.harvard.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthcare facilities: managing operations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-hcf.html. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 2.Ammerman BA Burke TA Jacobucci R, et al. Preliminary investigation of the association between COVID-19 and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in the US. 2020. Available at: https://psyarxiv.com/68djp/. Accessed April 27, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Auerbach J, Miller BF. COVID-19 exposes the cracks in our already fragile mental health system. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:969–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:819–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:510–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panchal N Kamal R Orgera K, et al. April 21 PCP, 2020. The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. 2020. Available at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare telemedicine health care provider fact sheet. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. COVID-19 Emergency Declaration Blanket Waivers for Health Care Providers. Baltimore, MD: Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2020. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Office of Civil Rights. Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth. 2020. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html. Accessed April 27, 2020.

- 10.Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Souza J, et al. Rapid growth in mental health telemedicine use among rural medicare beneficiaries, wide variation across states. Health Affairs. 2017;36:909–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uscher-Pines L, Bouskill K, Sousa J, et al. Experiences of Medicaid Programs and Health Centers in Implementing Telehealth. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2019. Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2564.html. Accessed April 27, 2020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain S, Khera R, Lin Z, et al. Availability of telemedicine services across hospitals in the United States in 2018: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:503–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trump DJ. Proclamation on declaring a national emergency concerning the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak. 2020. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/proclamation-declaring-national-emergency-concerning-novel-coronavirus-disease-covid-19-outbreak/. Accessed October 19, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA behavioral health treatment services locator. Available at: https://findtreatment.samhsa.gov/. Accessed April 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, et al. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Outpatient Visits: A Rebound Emerges. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2020. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/apr/impact-covid-19-outpatient-visits. Accessed August 4, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mervosh S, Lu D, Swales V. See which states and cities have told residents to stay at home. The New York Times. 2020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-stay-at-home-order.html. Accessed April 27, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.USA Facts. US Coronavirus Cases and Deaths: track COVID-19 data daily by state and county. 2020. Available at: https://usafacts.org/visualizations/coronavirus-covid-19-spread-map/. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- 18.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Mental Health Services Survey (N-MHSS): 2019. Data on Mental Health Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD; 2020.

- 20.Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs. Telehealth: delivering care safely during COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/coronavirus/telehealth/index.html. Accessed October 19, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.