Abstract

Background:

Personal care products (PCPs) are an important source of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) linked to adverse reproductive health outcomes.

Objective:

We evaluated EDC-associated PCP use and acculturation among Asian women.

Methods:

Our study included 227 foreign-born Chinese women ages 18–45 seeking obstetrics-gynecology care at community health centers (Boston, MA). Acculturation was measured by English-language use, length of US residence, and age at US entry. Self-reported use of PCPs (crème rinse/conditioner, shampoo, perfume/cologne, bar soap/body wash, liquid hand soap, moisturizer/lotion, colored cosmetics, sunscreen, and nail polish) in the last 48 hours was collected. Latent class analysis was used to identify usage patterns. We also conducted multivariable logistic to determine the cross-sectional associations of acculturation measures and the use of individual PCP types.

Results:

Those who used more PCP types, overall and by each type, tended to be more acculturated. Women who could speak English had 2.77 (95% CI: 1.10–7.76) times the odds of being high PCP users compared to their non-English speaking counterparts. English-language use was associated with higher odds of using perfume/cologne and nail polish.

Significance:

Our findings give insight about EDC-associated PCP use based on acculturation status, which can contribute to changes in immigrant health and health disparities.

Keywords: acculturation, personal care products, cosmetics, endocrine disruptors, Asian Continental Ancestry Group, Asian Americans

INTRODUCTION

There are wide racial/ethnic disparities in maternal and child health outcomes in the United States (US). In particular, Asian Americans have a unique set of disease burden and are the fastest growing ethnic group in the US [1], which makes understanding the reproductive health of this population of increasing importance. Cervical cancer rates are higher among certain Asian ethnic groups, especially Vietnamese and Korean [2], than non-Hispanic whites. Also, immigrant Asian American women have recently been found to have higher breast cancer risk than their US-born counterparts [3]. Within the Asian American population, Chinese makes up the largest origin group (23%) [1]. Chinese women have a particularly higher risk of developing gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), a strong risk factor for development of type 2 diabetes and of pregnancy complications, compared to non-Hispanic whites [4,5]. Despite having a lower body mass index, Asian ethnicity has independently been associated with higher insulin resistance during pregnancy [6]. Previous studies have focused on the contributions of dietary [7] and genetic [8] factors to GDM in Chinese women. However, differences in reproductive and birth outcomes between foreign- and US-born women demonstrate the need to investigate explanations beyond genetic components for racial/ethnic differences [9–11]. Of interest, there has been little consideration of environmental contributions to adverse maternal and child health outcomes among Asian Americans.

Environmental factors, including exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs), may play an important role in obstetric risks. Recent work showed higher mono-ethyl phthalate (MEP) and monobutyl phthalate (MBP) urinary concentrations in foreign-born Asians than in US-born Asians [12]. Moreover, MEP and MBP concentrations in foreign-born Asians became more similar to that in US-born Asians with longer US residence. Other studies have shown these metabolites to be related to significantly higher odds of excessive gestational weight gain, impaired glucose tolerance, and GDM [13,14]. Personal care products (PCPs) are an important source of EDCs commonly used by women [15], and a study among pregnant Taiwanese women linked elevated urinary phthalate concentrations with higher frequency of PCP use [16]. Changes in EDC-associated PCP use and possible subsequent EDC exposure may be an important mechanism underlying the shift in health outcomes associated with duration of US residence.

Acculturation may influence changes in social factors [17] that lead to the unequal exposure of environmental toxins. This concept aligns with the “negative acculturation hypothesis” that states that the health benefits observed among immigrants on average are attenuated with increased time in the US [18]. Interestingly, conditions such as obesity and diabetes are more prevalent in immigrants who have lived in the US longer compared to more recent immigrants [19,20]. However, acculturation has also been shown to play a protective role against GDM among Asian American women [21,22]. Because of uncertainty around the impact of acculturation on EDC-associated disease risk, it is imperative to understand the contribution of social processes that may be unique to growing segments of the US population.

Therefore, we sought to understand the association between acculturation and EDC-associated personal care product use in foreign-born Chinese women living in the US. Given that studies have shown that pregnancy can be a sensitive window of exposure, we conducted our study in a population of women seeking obstetrics-gynecology (OBGYN) care. We evaluated whether language spoken, length of US residence, and age at US entry were associated with EDC-associated PCP use. We hypothesized that women who had higher levels of acculturation would have a different usage pattern and higher EDC-associated PCP use compared to women with lower acculturation.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study Population

From July to August 2017, OBGYN patients at two South Cove Community Health Center (SCCHC) sites in the greater Boston metropolitan area were invited to participate in the study. SCCHC serves a predominantly Asian immigrant population. Over 98% of patients are Asian, and over 95% of patients are served using a language other than English. Approximately 90% of patients are at or below 200% of the federal poverty guideline, and the majority of patients use public insurance (i.e. Medicaid/CHIP/Medicare) [23]. Prior to their clinical appointment, participants in the waiting area were given the option to complete and submit a short, confidential anonymous two-page survey expected to take less than 10 minutes to complete in either English or simplified Chinese. Demographic survey questions were adapted from the US Census American Community Survey [24] and asked about current age, gender, race, and country of birth. Similar to Allen et al. [25], survey questions on spoken English-language use and length of US residence were adapted from the New Immigrant Survey [26]. Questions on the use of 13 common PCP types were from a questionnaire previously validated in non-Hispanic white pregnant women and women of reproductive age [27]. The Chinese survey was initially translated from the English survey by a native Mandarin speaker. Then, it was reviewed by bilingual South Cove clinical staff for readability and interpretability for clinical patients.

Eligibility criteria included being a female between ages 18 and 45 years old, seeking OBGYN care at the SCCHC, and being able to speak and write English, Mandarin or Cantonese (referred to as Chinese hereafter). Of the 342 self-implemented surveys collected, 315 (92.1%) participants met study eligibility. We further restricted the sample to those who were born in China due to sparse data on individuals born elsewhere (n=47). Of these 47 women, only a small proportion (12 women) were US-born Chinese women. Given that South Cove Community Health Center primarily serves Chinese immigrant populations, we would have limited power to conduct meaningful analyses on US-born Chinese women. We also excluded discordant survey responses for language acculturation measures (e.g. reported both being unable to speak English and speaking English with friends or at home) (n=19), leaving a sample size of 249 participants. Analysis was further restricted to exclude those with incomplete acculturation data (n=22), for a final sample of 227 participants. This study met the criteria for exemption of review from the Institutional Review Board of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Acculturation Measures

We measured degree of acculturation by English-language use, length of US residence, and age at US entry. English language use was assessed in three ways: whether she could speak English, whether she spoke English when with friends, and whether she spoke English at home. On the survey, women were asked to indicate all of the languages they spoke. Language measures were dichotomized with those who indicated that English was used, whether solely used or used along with another language, as speaking “any English” while those who indicated that no English was used as “no English” (reference group). Length of US residence was determined with the question, “If born outside of the U.S. how long have you lived in the U.S.?”. Length of US residence is a widely used measure of acculturation [28,29], and participants who had resided in the US for at least 10 years were considered to have long-term US residence based on previous studies [12,30]. Age at US entry was calculated by subtracting the length of US residence from self-reported age at the time of the survey and was dichotomized based on the median age (24 years).

PCP Types

Based on previous work indicating a set of personal care products as a primary sources for EDCs [31,32], we asked about binary (yes/no) use of deodorant, hair gel/spray, crème rinse/conditioner, shampoo, other haircare products, perfume/cologne, bar soap/body wash, liquid hand soap, moisturizer/lotion, shaving cream, colored cosmetics (e.g. foundation, blush, eye shadow, eye liner, mascara), sunscreen, and nail polish in the last 48 hours. Due to low-response for certain PCP categories, we evaluated a subset of nine PCP categories with at least a 10% prevalence: crème rinse/conditioner, shampoo, perfume/cologne, bar soap/body wash, liquid hand soap, lotion/moisturizer, colored cosmetics, sunscreen, and nail polish.

Covariates

Based on directed acyclic graphs, we identified educational attainment and site location as potential confounders. Both variables were used as proxies for individual socioeconomic status. Participants self-reported their highest degree of educational attainment in the US or elsewhere at the time of the survey (i.e. no schooling completed, up to high school – no diploma or GED, high school diploma or GED, some college but no degree, Associate degree, Bachelor’s degree, graduate degree, and don’t know). For analyses, highest educational attainment was collapsed into 3 categories: less than high school, high school, and more than high school. The study site location (i.e. Chinatown, MA or Quincy, MA) was also recorded.

Statistical Analyses

To understand usage patterns, we used latent class analysis (LCA) to identify groups of women with similar patterns of PCP usage. LCA [33] allows us to group multiple observed and correlated categorical responses into fewer unobserved and mutually exclusive latent classes. In this case, we categorized individuals into types of product users (latent variable) based on their PCP type usage patterns (observed variables). From two to eight classes, we systematically fit LCA models to obtain a parsimonious model. We considered Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC) as parsimony measures. They are the most widely used and consider both the maximum log-likelihood and the number of parameters estimated. Smaller AIC and BIC values, along with higher entropy, are indications of better model fit. Pearson’s χ2 goodness of fit and the likelihood ratio chi-square (G2) were also considered, where smaller χ2 and G2 values paired with fewer estimated parameters indicate better model fit [33].

Moderate probability of PCP type usage was defined to be between 0.25 to 0.75, and high probability of PCP type usage was set as over 0.75. For each latent class, we looked at descriptive statistics of sociodemographic characteristics and acculturation measures separately for comparison. We conducted a sensitivity analysis, running the LCA analysis on only those who have both complete acculturation and PCP type data (not imputed) (N=166). This yielded similar results (data not shown) as that ascertained using the data set with complete acculturation data but missing PCP usage data. Thus, the final LCA analysis used the latter data set with the larger sample size, consistent with what we later used for the logistic analyses, although not imputed.

To evaluate the association between acculturation measures and patterns of PCP use, we used multivariable logistic regression. We constructed three models, where model 1 estimated the unadjusted association, and model 2 adjusted for age at US entry and site location. Model 3 adjusted for age at US entry, site location, length US residence, and educational attainment.

Missing data on crème rinse/conditioner (8.4%), shampoo (10.6%), perfume/cologne (9.3%), bar soap/body wash (7.0%), liquid hand soap (6.6%), lotion/moisturizer (7.0%), colored cosmetics (8.4%), sunscreen (5.7%), nail polish (8.4%), and educational attainment (0.9%) were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) [34]. Fifty imputations were implemented, and 25 iterations were conducted for each imputation. Because PCP usage types were two level factors while educational attainment had more than two levels, we used imputation methods logistic regression and polytomous (unordered) regression, respectively. Compared to other multiple imputation techniques, MICE is often preferred over alternative joint models because it is more flexible by running regression models for each variable with missing data conditional on the rest of the variables.

In addition to evaluating the association between acculturation measures and patterns of PCP use, we also evaluated acculturation and binary use of each PCP type within the last 48 hours. For this, we used the imputed dataset to conduct multivariable logistic regression. Separate models were conducted for each PCP type as it related to each of the acculturation measures. In models evaluating language spoken and use of PCP types, we adjusted for length of US residence, age at US entry, site location, and educational attainment as potential confounders. The pooled odds ratio (OR) estimates were reported along with 95% confidence intervals. We also considered ability to speak English as a potential confounder and obtained similar pooled OR estimates (data not shown). The effect of length of US residence on use of PCP types (adjusted for age at US entry and site location) and age at US entry on use of PCP types (adjusted for site location) were also explored. Additionally, we conducted sensitivity analyses using the complete data (without imputations). All statistical analyses were performed with R version 3.6.1 (The R Foundation). Request for code used in this analysis can be made and will be evaluated by our study team.

RESULTS

Population Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics and acculturation measures of the participants overall and by latent class. Participants in this study were 32.7 ± 6.7 (mean ± SD) years old. The median age at US entry and length of US residence were 24.0 (range: 5.0–44.2) years and 7.0 (range: 0.2–34.0) years, respectively. Of the 227 women, 59 (26%) were considered to be long-term residents. Most participants were of low socioeconomic status. Almost 60% had attained up to a high school education, and 61.2% did not speak English. Subsequently, most did not speak English with friends (75.8%) or at home (91.2%). Compared to women recruited from the Chinatown site, a higher proportion of women from the Quincy site had at least a high school educational attainment (46.7% versus 35.1%) and spoke English (44.8% versus 32.4%) (Supplementary Table S1). The proportion of individuals who were able to speak any English, spoke any English with friends, and spoke any English at home were elevated among high PCP users (42.2%, 26.0%, and 9.9%, respectively) compared to moderate PCP users (20.0%, 14.3%, and 2.9%, respectively). Furthermore, high PCP users entered the US at a slightly younger age (median: 23.5 versus 25.8 years), with these users residing in the US for a longer period of time than moderate PCP users (median: 7.0 versus 4.0 years).

Table 1.

Summary of sociodemographic characteristics and acculturation measures overall and by latent class

| Total (n=227) | High PCP users (n=192) | Moderate PCP users (n=35) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 32.7 (6.7) | 32.5 (6.6) | 34.1 (7.1) |

| Age at entry into US | |||

| Median (IQR) | 24.0 (20.0–29.0) | 23.5 (20.0–29.0) | 25.8 (21.0–31.5) |

| Range | 5.0–44.2 | 5.0–44.2 | 15.0–42.0 |

| Length of US residence | |||

| Median (IQR) | 7.0 (3.0–11.0) | 7.0 (3.8–11.0) | 4.0 (1.8–10.5) |

| Range | 0.2–34.0 | 0.2–34.0 | 0.3–26.0 |

| Educational attainment, n (%) | |||

| < High School | 50 (22.1) | 39 (20.5) | 11 (31.4) |

| High School | 83 (36.4) | 69 (36.3) | 13 (37.1) |

| > High School | 93 (41.0) | 81 (42.6) | 11 (31.4) |

| Don’t know | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Any English, n (%) | |||

| Overall | 88 (38.8) | 81 (42.2) | 7 (20.0) |

| With friends | 55 (24.2) | 50 (26.0) | 5 (14.3) |

| At home | 20 (8.8) | 19 (9.9) | 1 (2.9) |

SD=standard deviation; IQR=interquartile range

Product Use Patterns

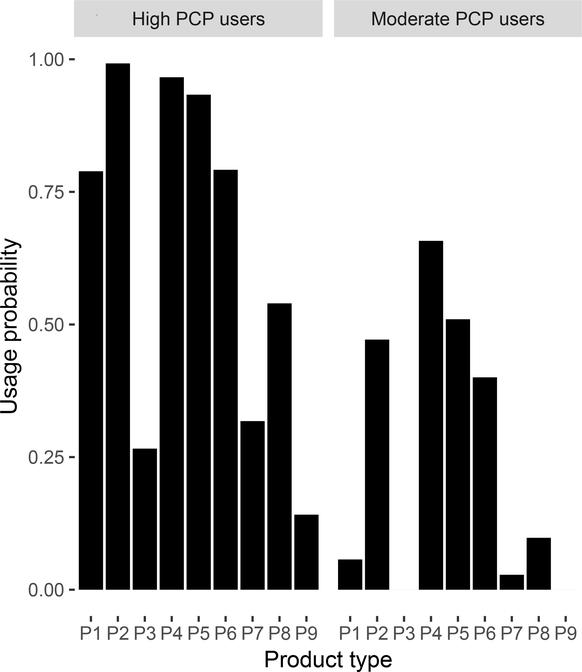

Based on the fit statistics and entropy for varying classes (Table S2), two latent classes were identified: high PCP users and moderate PCP users. Fig. 1 shows product type usage by latent class, and Table S3 summarizes the probability of product type usage within each latent class. High PCP users were highly likely to use crème rinse/conditioner, shampoo, bar soap/body wash, liquid hand soap, and hand/body lotion/moisturizer, as well as moderately likely to use perfume/cologne, colored cosmetics, and sunscreen. Moderate PCP users were moderately likely to use shampoo, bar soap/body wash, liquid hand soap, and hand/body lotion/moisturizer. While high PCP users used perfume/cologne and nail polish minimally (probability=0.27 and 0.14, respectively), neither product types were used at all by moderate PCP users.

Fig. 1:

Black bars denote the probability of using each PCP type in the last 48 hours among high PCP users (left panel) and moderate PCP users (right panel). Abbreviations: P1, crème rinse/conditioner; P2: shampoo; P3: perfume/cologne; P4: bar soap/body wash; P5: liquid hand soap; P6: lotion/moisturizer; P7: colored cosmetics; P8: sunscreen; P9: nail polish

Table 2 and Table S4 show the association between acculturation measures, English language use along with length of US residence and age at US entry, and PCP use pattern, respectively. Women who could speak any English had 2.77 (95% CI: 1.10–7.76) times the odds of being in the high PCP user versus moderate PCP user class than non-English speaking women. In addition, there was suggestion that individuals who spoke any English with their friends or at home and earlier age at US entry were more likely to be high PCP users; however, confidence intervals were quite wide.

Table 2.

English language acculturation measures as predictors of high PCP user versus moderate PCP user class*.

| Speaks English (any versus none) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall OR (95% CI) | With friends OR (95% CI) | At home OR (95% CI) | |

| Model 1a | 2.92 (1.28, 7.56) | 2.11 (0.84, 6.46) | 3.73 (0.74, 68.21) |

| Model 2b | 2.61 (1.12, 6.84) | 1.83 (0.70, 5.71) | 3.39 (0.65, 62.27) |

| Model 3c | 2.77 (1.10, 7.76) | 1.80 (0.66, 5.77) | 3.22 (0.60, 59.75) |

unadjusted

adjusted for age at US entry and site location

adjusted for age at US entry, site location, length of US residence, and educational attainment

High PCP users class included 192 women, and moderate PCP users class included 35 women based on the latent class analyses conducted.

Acculturation and Individual PCP types

Table 3 summarizes the association between English language use and individual product types. Being able to speak any English was not associated with use of any individual product type in the last 48 hours. However, nail polish use was positively associated with participants’ ability to speak English with friends (OR=3.61, 95% CI: 1.39–9.33). Perfume/cologne use was also associated with speaking English with friends (OR=2.79, 95% CI: 1.31–5.97) and at home (OR=3.78, 95% CI: 1.36–10.53). While earlier age at US entry was associated with use of colored cosmetics (OR=2.31, 95% CI: 1.22–4.38), long-term US residence was not associated with use of any individual product types we investigated (Table S5).

Table 3.

Associations between English language acculturation measures and individual product type usage

| Speaks English (any versus none) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall OR (95% CI) | With friends OR (95% CI) | At home OR (95% CI) | |

| Crème rinse/conditioner | 1.43 (0.73, 2.84) | 1.32 (0.62, 2.79) | 0.84 (0.30, 2.35) |

| Shampoo | 1.92 (0.64, 5.75) | 1.21 (0.39, 3.78) | 0.92 (0.18, 4.65) |

| Perfume/cologne | 1.96 (0.93, 4.09) | 2.79 (1.31, 5.97) | 3.78 (1.36, 10.53) |

| Bar soap/body wash | 1.78 (0.59, 5.43) | 1.99 (0.53, 7.42) | NE |

| Liquid hand soap | 2.90 (1.00, 8.46) | 2.75 (0.70, 10.72) | NE |

| Lotion/moisturizer | 1.21 (0.59, 2.48) | 0.69 (0.33, 1.46) | 0.66 (0.23, 1.90) |

| Colored cosmetics | 1.69 (0.83, 3.43) | 1.07 (0.51, 2.27) | 0.99 (0.33, 2.93) |

| Sunscreen | 1.57 (0.83, 2.97) | 1.07 (0.55, 2.09) | 1.45 (0.54, 3.87) |

| Nail polish | 2.06 (0.79, 5.40) | 3.61 (1.39, 9.33) | 2.71 (0.82, 8.98) |

All models adjusted for age at US entry, site location, length of US residence, and educational attainment.

NE: non-estimable – model could not converge because usage groups were unbalance

Sensitivity Analyses

Associations between acculturation measures and individual product type using the complete dataset (without imputations) are summarized in Supplementary Materials (Table S6 and Table S7). While acculturation measures using the dataset with and without imputations were both associated with perfume/cologne, colored cosmetics, and nail polish use, acculturation measures using the dataset without imputations were additionally associated with use of crème rise/conditioner, bar soap/body wash, and liquid hand soap. Given that the confidence intervals are wide, these additional associations could be driven by missingness, and using the imputed dataset gave more precise and conservative results.

DISCUSSION

In this study among foreign-born Chinese women living in the US, we found that a higher degree of acculturation was associated with higher EDC-associated PCP use. Differences between moderate and high PCP users were most pronounced for perfume/cologne and nail polish use in the last 48 hours. We saw no use of these PCPs at all among moderate PCP users compared to some use among high PCP users, who also showed higher degrees of acculturation. English-language use, a specific aspect of acculturation, was observed to be associated with use of a greater variety of product types, especially perfume/cologne and nail polish. These findings may suggest that acculturation can contribute to EDC-associated PCP use, with possible implications for associated adverse health outcomes in this population.

While phenols, such as triclosan, are commonly found in certain PCPs (e.g. liquid soap) for its antimicrobial property, low molecular weight phthalates are more widely used in PCPs as solvents. Diethyl phthalate, the parent compound of the metabolite MEP, is mostly used in fragranced products. The parent compound of MBP, di-butyl phthalate, is used in personal care products, including nail polish [35]. High PCP users in the present study used some perfume/cologne and nail polish, while moderate PCP users used neither of these PCPs. Furthermore, predictors of acculturation (i.e. English language use) were associated with higher use of perfume/cologne and nail polish. Studies have consistently shown that changes in EDC concentrations and disease vary with length of US residence, although the direction of that change differs depending on the metabolite. One study [12] found higher MEP and MBP phthalate metabolite concentrations in foreign-born Asians (geometric mean: 22.8 and 8.4 ng/mL, respectively) than in US-born Asians (geometric mean: 16.9 and 4.4 ng/mL, respectively). These metabolite concentrations steadily decreased with longer US residence for immigrants and were almost indistinguishable to levels in US-born individuals for immigrants who resided in the US for over 30 years. Consistent with the trend observed for MEP and MBP, urinary concentration of mono benzyl phthalate (MBzP) among immigrants became more similar to that among US-born individuals with longer US residence. US-born individuals had significantly higher MBzP urinary concentration, and MBzP rose with length of US residence. In a study among Mexican-American pregnant women [36], urinary concentration of MBzP was also found to increase with longer length of US residence and with English as a primary language.

Our findings also align with the “negative acculturation hypothesis” and illustrates a potential mechanism by which EDC exposure can vary within the population. The “negative acculturation hypothesis” assumes that immigrant health declines with longer US residence as immigrants adopt unhealthy Western lifestyles and shed protective ethnic health behaviors, such as their native diet and cultural practices [18]. Under this hypothesis, we would view our findings of higher use of perfume/cologne and nail polish among more acculturated women as evidence of Chinese women adopting Western behaviors. Future works on understanding product usage patterns by nativity and race/ethnicity are needed to replicate these findings and to further determine the drivers of product use patterns and change based on immigrant status and acculturation. While this hypothesis appears to hold true for some outcomes among Asian immigrants (e.g. body weight), other factors, such as stress from migrating to a different country or racial barriers, may also influence observed health declines with longer US residence. Future work should be aimed at understanding the factors, such as product availability and social experience, that might lead to higher use of EDC-associated PCPs.

Emerging sociological and psychological work in acculturation argues that retention of one’s native culture and adapting to the dominant culture is a dynamic process [37]. Acculturation involves contact with a new culture and the ways that contact is dealt with. As such, increasing acculturation typically refers to taking on norms of the dominant culture [38]. For some immigrants, acculturation could mean acquiring new behaviors, including consumption patterns, and social skills as part of cultural learning, while shedding aspects of their previous behaviors to adapt to the new cultural context [39]. For others, acquired behaviors from the new culture may exist alongside native culture. Still, acculturation has been observed to be a strong determinant of brand choice, with brand preferences from the host country dependent on the degree of acculturation [40]. We observed English language use to be associated with higher use of almost all the products evaluated in this study. A closer look at the language acculturation measures revealed that speaking English with friends and at home were indications of a different level of acculturation than simply being able to speak any English, particularly for perfume and nail polish use. This finding may be expected given that speaking English with friends or at home could likely be better indicators of social ties and community engagement mapping onto behaviors that more meaningfully drive product use than simply the ability to speak any English.

Drivers of US racial/ethnic disparities in PCP use, such as racially/ethnically-targeted marketing, lack of US regulation, and cultural norms/stigma better studied in other racial/ethnic groups may also apply to Asian Americans and explain our observed differences in PCP use by acculturation levels [41]. For example, Black women are more likely to use PCPs, including hair products, and initiate product use at earlier ages than White women. These products often contain hormonally-active products such as parabens and phthalates [42, 43, 44, 45]. Notably, Latinas are the leading consumers of beauty products [41]. However, Asians contribute over 70% of spending on skin care products [41]. For Asians immigrants, changes in the concept of beauty, social networks, economic mobility, and purchasing power could impact access to PCPs. Furthermore, these factors may influence higher use of certain types of PCPs, as seen in the present study.

Although different products types and brands have different EDC profiles, PCPs are an important source of EDCs, and increased use of PCPs is correlated with higher urinary phthalate metabolite concentration, especially MEP [16]. Prior work suggest that EDCs play a key role in reproductive health differences by race/ethnicity [41,46]. A prospective study [42] on pregnant Black and White pregnant women in Southeastern US found that Black pregnant mothers had higher urinary concentration of low molecular weight phthalate metabolites common in PCPs than their White counterparts. Indeed, elevated risk of preterm birth was associated with higher mono-isobutyl phthalate (MiBP) and MEP urinary concentrations (p-interaction: 0.08 and 0.02, respectively) among Black women in the population. Another study [47] additionally looked at EDCs across pregnancy in Hispanics and found higher concentrations of MEP and MiBP in Black and Hispanic women than in White women. EDC exposure and women’s reproductive health is understudied and not characterized well in Asian Americans, much less Chinese Americans. In studies that do include Asian Americans, their risk of GDM is particularly high, but urinary phthalate levels have actually been found to be lower in Asians than Blacks, Hispanics, and often times Whites as well [12,46]. Still, we see urinary MEP and MBP concentrations, which are related to GDM, change by length of US residence [48]. Interestingly, prevalence of GDM is significantly lower among Chinese women born in the US compared to those born outside of the US [22]. Geographic differences in urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations, including higher MiBP from urine samples from China have been noted [49]. In addition, previous work notes that phthalate metabolites vary based on a number of acculturation measures. Given that our study shows that product use also varied by some of the same acculturation measures, it is plausible that EDC-associated PCPs could be contributing to differences in EDC exposures, with implications on associated health outcomes related to acculturation. Future studies need to evaluate sources of EDC to understand how acculturation and product use can drive EDC exposure and impact health outcomes.

Our study has several limitations. We asked participants to recall their product use in the last 48 hours. While the short time frame allowed women to accurately recall their product use, it may not reflect general, chronic use. Furthermore, the survey and the 13 PCPs listed were not designed for and may not be comprehensive for this population, potentially omitting culturally-important PCP types. Another limitation of this study is the lack of biomarker data, as PCP use in this population may not correlate with EDC exposure. However, PCP use and EDC exposure has been found to be correlated in other populations, including Asian populations [16,27]. Although the survey development process as recommended by Tsang et al. [50] was completed, pilot testing in a subset of participants was not conducted, and the lack of validation of the translated instrument may affect the observations related to language and PCP use. We recognize that the concept of beauty, social network, culture adaptation, purchasing power, and pressure to assimilate may differ by a number of variables, including age and education, that may modify the association between acculturation measures and PCP use. However, we lacked the statistical power in the present study, and encourage future studies, to investigate effect measure modification. Also, this study captured only a few aspects of the complex and dynamic process of acculturation. For example, women who completed their education in the US may have different behavioral patterns compared to those who completed their education outside of the US. But, the measures we used were consistent with prior studies [25,51] and reduced participation burden. These measures have also been found to be positively correlated with several validated acculturation scales widely used in Asian American populations [52,53]. Finally, there may be issues with multiple comparisons. However, the findings from this study still suggests trends that warrant a closer look at how PCP use changes among immigrants. Future studies will need to better assess long-term PCP use (i.e. biomarkers) with a more multidimensional acculturation scale (e.g. General Ethnicity Questionnaire [54]) and more comprehensive list of PCPs.

Our study also includes several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between acculturation and PCP use, specifically in Chinese women of reproductive age. The study sample was restricted to this population to assess the unique patterns of EDC-associated product use in a large proportion of the immigrant population, which allowed us to reduce heterogeneity by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and nativity. Even within this homogenous sample, we were able to detect heterogeneity by English language ability and latent classes of PCP use. Our survey captured multiple measures of acculturation and a wide range of product types. Finally, this work can be informative of EDC exposure patterns and associated disease risk in an understudied population, with ability to inform how acculturation may drive environmental exposures and associated disease in a rapidly increasing subset of the US population.

In conclusion, higher degree of acculturation, especially captured by conversational English language use, was related to higher use of EDC-associated PCPs in the last 48 hours. These usage patterns may suggest that Chinese women who have a higher level of acculturation could have greater EDC exposure, with implications for increased risk of EDC-associated diseases. Given that PCP use was used as a proxy for EDC exposure in this study, further research is needed to characterize actual products and their EDC profiles. Further investigation of long-term product use beyond the past 48 hours in EDC sources not traditionally collected in existing PCP measures is also needed in Chinese women of reproductive age living in the US to understand the value of PCP use as a target for intervention in reducing health disparities.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We offer our special thanks to the participants and leadership of South Cove Community Health Center in Chinatown, MA and Quincy, MA.

FUNDING

This study was supported by grant NIH/NIEHS T32ES007069, P30ES000002, R01ES026166. This work was funded, in part, by the Intramural Program at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS, Z1AES103325–01).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Budiman A, Cilluffo A, Ruiz NG. Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S. [Internet]. Pew Research Center. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/22/key-facts-about-asian-origin-groups-in-the-u-s/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang SS, Carreon JD, Gomez SL, Devesa SS. Cervical Cancer Incidence Among 6 Asian Ethnic Groups in the United States, 1996 Through 2004. Cancer. 2010. February 15;116(4):949–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morey BN. Higher Breast Cancer Risk Among Immigrant Asian American Women Than Among US-Born Asian American Women . Prev Chronic Dis [Internet]. 2019;16. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2019/18_0221.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Obstetrical Outcomes and Care: Prevalence and Determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010. April;202(4):335–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pu J, Zhao B, Wang EJ, Nimbal V, Osmundson S, Kunz L, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Gestational Diabetes Prevalence and Contribution of Common Risk Factors. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015. September;29(5):436–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Retnakaran R, Hanley AJG, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B. Ethnicity Modifies the Effect of Obesity on Insulin Resistance in Pregnancy: A Comparison of Asian, South Asian, and Caucasian Women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006. January;91(1):93–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wan CS, Nankervis A, Teede H, Aroni R. Dietary intervention strategies for ethnic Chinese women with gestational diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Diet. 2019;76(2):211–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie K, Zhang Y, Wen J, Chen T, Kong J, Zhang J, et al. Genetic predisposition to gestational glucose metabolism and gestational diabetes mellitus risk in a Chinese population. J Diabetes. 2019. November;11(11):869–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urquia ML, Glazier RH, Blondel B, Zeitlin J, Gissler M, Macfarlane A, et al. International migration and adverse birth outcomes: role of ethnicity, region of origin and destination. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010. March 1;64(3):243–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tapales A, Douglas-Hall A, Whitehead H. The sexual and reproductive health of foreign-born women in the United States. Contraception. 2018. July;98(1):47–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh GK, Yu SM. Adverse pregnancy outcomes: differences between US- and foreign-born women in major US racial and ethnic groups. Am J Public Health. 1996. June;86(6):837–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitro SD, Chu MT, Dodson RE, Adamkiewicz G, Chie L, Brown FM, et al. Phthalate metabolite exposures among immigrants living in the United States: Findings from NHANES, 1999–2014. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2019. January;29(1):71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James-Todd TM, Meeker JD, Huang T, Hauser R, Ferguson KK, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. Pregnancy urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations and gestational diabetes risk factors. Environ Int. 2016. November;96:118–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaffer RM, Ferguson KK, Sheppard L, James-Todd T, Butts S, Chandrasekaran S, et al. Maternal urinary phthalate metabolites in relation to gestational diabetes and glucose intolerance during pregnancy. Environ Int. 2019. February 1;123:588–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parlett LE, Calafat AM, Swan SH. Women’s exposure to phthalates in relation to use of personal care products. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2013. March;23(2):197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsieh C-J, Chang Y-H, Hu A, Chen M-L, Sun C-W, Situmorang RF, et al. Personal care products use and phthalate exposure levels among pregnant women. Sci Total Environ. 2019. January;648:135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keister LA, Vallejo JA, Aronson B. Chinese Immigrant Wealth: Heterogeneity in Adaptation. PLOS ONE. 2016. December 15;11(12):e0168043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ro A The Longer You Stay, the Worse Your Health? A Critical Review of the Negative Acculturation Theory among Asian Immigrants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014. August;11(8):8038–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afable A, Yeh M-C, Trivedi T, Andrews E, Wylie-Rosett J. Duration of US Residence and Obesity Risk in NYC Chinese Immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health Cent Minor Public Health. 2016. June;18(3):624–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oza-Frank R, Stephenson R, Venkat Narayan KM. Diabetes Prevalence by Length of Residence Among US Immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011. February 1;13(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen L Influence of Acculturation on Risk for Gestational Diabetes Among Asian Women. Prev Chronic Dis [Internet]. 2019;16. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2019/19_0212.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedderson MM, Darbinian JA, Ferrara A. Disparities in the risk of gestational diabetes by race-ethnicity and country of birth: Gestational diabetes and race/ethnicity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2010. July 7;24(5):441–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Health Resources & Services Administration. 2018 South Cove Community Health Ctr, Inc. Health Center Program Awardee Data [Internet]. Available from: https://bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/datacenter.aspx?q=d&bid=010710&state=MA&year=2018

- 24.US Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS) [Internet]. The United States Census Bureau. Available from: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen JD, Caspi C, Yang M, Leyva B, Stoddard AM, Tamers S, et al. Pathways between acculturation and health behaviors among residents of low-income housing: The mediating role of social and contextual factors. Soc Sci Med. 2014. December;123:26–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith GJ, Massey Douglas S, Rosenzweig Mark R, and James P. The New Immigrant Survey in the U.S.: The Experience over Time [Internet]. migrationpolicy.org. 2003. Available from: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/new-immigrant-survey-us-experience-over-time

- 27.Braun JM, Just AC, Williams PL, Smith KW, Calafat AM, Hauser R. Personal care product use and urinary phthalate metabolite and paraben concentrations during pregnancy among women from a fertility clinic. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2014. September;24(5):459–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Brien MJ. Acculturation and the Prevalence of Diabetes in US Latino Adults, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2010. Prev Chronic Dis [Internet]. 2014;11. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2014/14_0142.htm [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koya DL, Egede LE. Association Between Length of Residence and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors Among an Ethnically Diverse Group of United States Immigrants. J Gen Intern Med. 2007. June;22(6):841–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yvonne Commodore-Mensah, Nwakaego Ukonu, Olawunmi Obisesan, Kumi Aboagye Jonathan, Charles Agyemang, Reilly Carolyn M, et al. Length of Residence in the United States is Associated With a Higher Prevalence of Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Immigrants: A Contemporary Analysis of the National Health Interview Survey. J Am Heart Assoc. 5(11):e004059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Endocrine Disruptors [Internet]. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Available from: https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/endocrine/index.cfm [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weatherly LM, Gosse JA. Triclosan exposure, transformation, and human health effects. J Toxicol Environ Health Part B. 2017. November 17;20(8):447–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Linzer DA, Lewis JB. poLCA: An R Package for Polytomous Variable Latent Class Analysis. J Stat Softw. 2011. June;42(10). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azur MJ, Stuart EA, Frangakis C, Leaf PJ. Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work?: Multiple imputation by chained equations. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011. March;20(1):40–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benjamin S, Masai E, Kamimura N, Takahashi K, Anderson RC, Faisal PA. Phthalates impact human health: Epidemiological evidences and plausible mechanism of action. J Hazard Mater. 2017. October 15;340:360–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holland N, Huen K, Tran V, Street K, Nguyen B, Bradman A, et al. Urinary Phthalate Metabolites and Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in a Mexican-American Cohort: Variability in Early and Late Pregnancy. Toxics. 2016. March;4(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berry JW. Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation. Appl Psychol. 1997;46(1):5–34. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moore KA, Weinberg BD, Berger PD. The Mitigating Effects of Acculturation on Consumer Behavior. 2012;3(9):5. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berry JW. A Psychology of Immigration. J Soc Issues. 2001;57(3):615–31. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segev S, Ruvio A, Shoham A, Velan D. Acculturation and consumer loyalty among immigrants: a cross-national study. Eur J Mark. 2014. September 2;48(9/10):1579–99. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zota AR, Shamasunder B. The Environmental Injustice of Beauty: Framing Chemical Exposures from Beauty Products as a Health Disparities Concern. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017. October;217(4):418.e1–418.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bloom MS, Wenzel AG, Brock JW, Kucklick JR, Wineland RJ, Cruze L, et al. Racial disparity in maternal phthalates exposure; Association with racial disparity in fetal growth and birth outcomes. Environ Int. 2019. June 1;127:473–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.James-todd T, Senie R, Terry MB. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Hormonally-Active Hair Product Use: A Plausible Risk Factor for Health Disparities. J Immigr Minor Health N Y. 2012. June;14(3):506–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor KW, Baird DD, Herring AH, Engel LS, Nichols HB, Sandler DP, et al. Associations among personal care product use patterns and exogenous hormone use in the NIEHS Sister Study. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2017. September;27(5):458–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaston SA, James-Todd T, Harmon Q, Taylor KW, Baird D, Jackson CL. Chemical/straightening and other hair product usage during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood among African-American women: potential implications for health. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2020. January;30(1):86–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.James-Todd TM, Chiu Y-H, Zota AR. Racial/ethnic disparities in environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals and women’s reproductive health outcomes: epidemiological examples across the life course. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2016. June;3(2):161–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.James-Todd T, Meeker J, Huang T, Hauser R, Seely E, Ferguson K, et al. Racial and Ethnic Variations in Phthalate Metabolite Concentrations across Pregnancy. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2017. March;27(2):160–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitro SD, Chu MT, Dodson RE, Adamkiewicz G, Chie L, Brown FM, et al. Phthalate metabolite exposures among immigrants living in the United States: Findings from NHANES, 1999–2014. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2019. January;29(1):71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo Y, Alomirah H, Cho H-S, Minh TB, Mohd MA, Nakata H, et al. Occurrence of Phthalate Metabolites in Human Urine from Several Asian Countries. Environ Sci Technol. 2011. April;45(7):3138–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsang S, Royse CF, Terkawi AS. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017. May;11(Suppl 1):S80–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kandula NR, Diez-Roux AV, Chan C, Daviglus ML, Jackson SA, Ni H, et al. Association of Acculturation Levels and Prevalence of Diabetes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Diabetes Care. 2008. August 1;31(8):1621–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benet-Martínez V, Haritatos J. Bicultural identity integration (BII): components and psychosocial antecedents. J Pers. 2005. August;73(4):1015–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suinn R, Rickard-Figueroa K, Lew S, Vigil P. The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale: An Initial Report. Educ Psychol Meas. 1987;47(2):401–7. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsai JL. General Ethnicity Questionnaire | Culture and Emotion Lab [Internet]. Available from: https://culture-emotion-lab.stanford.edu/projects/toolsmaterials/general-ethnicity-questionnaire

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.