Abstract

The development of tumors is a complex pathological process involving multiple factors, multiple steps, and multiple genes. Their prevention and treatment have always been a difficult problem at present. A large number of studies have proved that the tumor microenvironment plays an important role in the progression of tumors. The tumor microenvironment is the place where tumor cells depend for survival, and it plays an important role in regulating the growth, proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion of tumor cells. P2X purinergic receptors, which depend on the ATP ion channel, can be activated by ATP in the tumor microenvironment, and by mediating tumor cells and related cells (such as immune cells) in the tumor microenvironment. They play an important regulatory role on the effects of the skeleton, membrane fluidity, and intracellular molecular metabolism of tumor cells. Therefore, here, we outlined the biological characteristics of P2X purinergic receptors, described the effect of tumor microenvironment on tumor progression, and discussed the effect of ATP on tumor. Moreover, we explored the role of P2X purinergic receptors in the development of tumors and anti-tumor therapy. These data indicate that P2X purinergic receptors may be used as another potential pharmacological target for tumor prevention and treatment.

Keywords: P2X purinergic receptors, Tumor microenvironment, Tumors, ATP

Introduction

The development of tumors is inseparable from the tumor microenvironment, which is vital to tumor survival. Tumor cells can be more suitable for their own survival and development by changing the tumor microenvironment (such as PH, acid, oxygen, some molecular substances) [1, 2]. Recently studies have confirmed that the molecular structure of tumor microenvironment is a new regulatory target for tumor treatment [3]. After tumorigenesis, tumor cells and other cells invaded by tumors can release large amounts of ATP into the extracellular space, and regulate the progression of tumors by mediating other molecular substances in the microenvironment [4, 5]. Adenosine, one of the important components in the tumor microenvironment, can drive tumors to develop immune tolerance through immunosuppression, thereby reducing the therapeutic effect of drugs [6]. These adenosines can be produced by the microenvironment, where ATP can regulate tumor progression by acting on P2X purinergic receptors on tumor cell membranes and other cell membranes [7, 8]. Although many factors are involved in the development of tumors, the role of ATP ion channel P2X purinergic receptors in the development of tumors, including solid tumors and blood-borne tumors (such as multiple myeloma), has been recognized and affirmed by different studies, confirming their contribution to tumor progression [9, 10]. Currently, P2X purinergic receptors can be divided into seven subtypes (1–7) [11]. Especially the biological function of P2X7 receptor in regulating tumor cells has received extensive attention and attracting the interest of many researchers. Nevertheless, there is still a lack of in-depth understanding and insight into the molecular mechanism of P2X purinergic receptors regulating the development of tumors. It is understood that P2X purinergic receptors can be activated by ATP. The activated P2X purinergic receptors can open ion channels on the cell membrane (calcium ion, sodium ion influx, and potassium ion outflow), and activate different signaling pathways in the cells, thereby changing the fate of tumor cells [5]. Moreover, immune cells and inflammatory cells in the tumor microenvironment are also the points of action of P2X purinergic receptors, and P2X purinergic receptors play an important role in tumor progression and treatment by mediating these cells [12, 13]. Here, we explored the internal correlation between P2X purinergic receptors, ATP, tumor microenvironment, and tumor, and provided some powerful value information for the prevention and treatment of tumors.

Biological characteristics of P2X purinergic receptors

P2X purinergic receptors exert their biological characteristics in their genetic structure. Although P2X purinergic receptors are divided into 7 subtypes, each member of the P2X purine family consists of three subunits, namely, intracellular domain, transmembrane domain, and extracellular domain [14]. Intracellular contains C-terminal and N-terminal domains, and the N-terminal sequence is short, which has the property of regulating calcium ion influx. The C-terminal sequence is relatively long, which can affect the binding with other proteins [15, 16]. Importantly, compared with other P2X subtypes (1–6), the unique biological function of P2X7 receptor involved in physiological and disease responses lies in the C-terminal sequence. C-terminal sequence of P2X7 receptor is the longest in the P2X purinergic receptors, which has the effect of changing a variety of physiological functions in the body (such as synthesis of lipopolysaccharide and formation of mold holes) [5]. Recently, different studies have found that changes in P2X7 receptor gene single-nucleotide polymorphisms can enhance or reduce its biological functions, and have a significant contribution to the development of the disease [17–19]. Two transmembrane domains, TM1 and TM2, can regulate the opening of ion channels on the cell membrane. Extracellular domain is also a special domain for P2X purinergic receptors activation and fulfilling their function, and has an ATP binding site [20–22]. Generally speaking, under physiological conditions, P2X purinergic receptors are in an inactive state, and their biological functions are restricted. However, when the body is in a pathological state, the release of ATP increases, which activates P2X purinergic receptors, and participates in the response process of many diseases [23, 24]. It is worth mentioning that P2X7 receptor has a low affinity for ATP, so a higher ATP concentration is required to be activated (> 100 μM) [25, 26].

P2X purinergic receptors are widely expressed in the immune system and nervous system. They play a functional role in immune, inflammatory response, and neurological diseases (such as depression, Alzheimer’s disease, and pain) [27–29]. For example, P2X4 receptor was first cloned and discovered in rat brain tissue [30]. P2X7 receptor was first found in macrophages and lymphocytes [31]. P2X2/3 receptors are discovered and recognized in neurons [32]. With the continuous research and exploration of P2X purinergic receptors function, it is found that P2X purinergic receptors are widely expressed in various tissues and structures of the body, such as respiratory system, digestive system, and cardiovascular system [33–35]. Recently, researchers have achieved a major breakthrough in that P2X purinergic receptors is involved in tumor progression, especially P2X7 receptor, which is expressed in most tumor cells and plays an important regulatory role in the progression of tumors [36, 37]. Moreover, given that P2X purinergic receptors are widely expressed in the nervous system, researchers have bridged and connected the nervous system and the development of tumors [38]. Indeed, studies have found that the nervous system also plays a certain role in promoting tumor progression. While P2X purinergic receptors can not only mediate the nervous system to regulate the development of tumors but also directly affect tumor cells (P2X7 receptor) or indirectly affect the fate of tumors (P2X4 receptor) through the tumor microenvironment [39, 40]. Another difference between P2X7 receptor and other P2X purinergic receptors is its ability to regulate the opening of ions on the cell membrane. P2X7 receptor is in a low-activity state to open ion channels and promote cell activity, while in a prolonged ATP action or continuous stimulation of activator, P2C7 receptor can cause the ion channels on the membrane to continue to expand to form membrane pores and mediate cell apoptosis and death [41]. This is also the particularity of P2X7 receptor performing dual functions in different active states. While P2X4 receptor is different from other P2X purinergic receptors in that it has a greater permeability to calcium ions, allowing some macromolecular substances to enter the cell and affect cell activity [42].

The connection between tumor microenvironment and tumor

Tumor microenvironment contains many components, such as immune cells (such as tumor-associated macrophages, MDSC) [43, 44], stromal cells [45], subcellular elements (such as exocrine bodies) [46], laminin [47], and growth factors [48] which can induce tumor cell migration and invasion. Indeed, the progression of tumors does not depend on the tumor cells themselves, but is mediated by the regulation of the tumor microenvironment [49, 50]. Tumor cells can modify their living environment through autocrine and paracrine methods to be more suitable for maintaining their own survival [51]. Moreover, microRNAs play an important role in the differentiation, proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells, and may also play a regulatory function through the P2X purinergic signal axis (P2X7 receptor) [52, 53]. Studies have shown that overexpression of miR-150 suppresses the level of P2X7 receptor and promotes the growth of breast cancer cells [54]. Further research found that miR-216B could directly target P2X7R, downregulate the mRNA and protein levels of endogenous P2X7R, reduce Bcl-2 expression and increase caspase-3 expression, and inhibit the proliferation of breast cancer [55]. Furthermore, proteases play an irreplaceable role in the development of tumors, and can regulate the progression of tumors through the metabolic effects of P2X purinergic receptors [56, 57]. Although the regulation mechanism of tumor microenvironment on the development of tumors is complex, the regulation of tumor microenvironment on tumor and the mechanism of tumor cell resistance have been uniformly understood, mainly including the following aspects:

Hypoxia: Hypoxia-inducible factor is a key metabolic factor that induces hypoxia. Studies have shown that inhibiting hypoxia-induced HIF-1α can significantly increase the sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapy drugs [58]. Studies have confirmed that hypoxia is also one of the key factors leading to tumor resistance [59]. Indeed, the immortal proliferation ability of tumor cells has high oxygen consumption capacity, and the low oxygen state in the microenvironment can induce drug resistance of tumor cells and promote their proliferation and migration [60, 61]. Moreover, hypoxia can stimulate abnormal growth of blood vessels and provide a nutritional environment for tumor cell growth [62, 63]. Furthermore, hypoxia can also maintain the characteristics of tumor stem cells and maintain the growth of tumor cells [64]. Studies have shown that maintaining the metabolic and functional characteristics of osteosarcoma stem cells under hypoxic conditions, leading to tumor resistance [65]. In addition, the hypoxic environment can also induce the formation of tumor EMT and promote tumor invasion. Studies have shown that overexpression of HIF-1α can induce EMT changes in breast cancer cells and promote breast cancer invasion [66].

Acidic environment: Abnormal sugar metabolism and Warburg effect in tumor cells can lead to the production of protons and acidic metabolites, which leads to changes in the PH regulation function of the microenvironment [67]. Long-term low PH in the tumor microenvironment can induce chromosomal instability, the change of cell cycle, gene mutation and cell division, and promote the growth and metastasis of tumor cells [68–70]. Studies have shown that the cultivation of prostate cancer cells (R3327-AT-1) and breast cancer cells (Walker-256) in a hypoxic and acidic environment (PH 6.6) in vitro promotes the growth and proliferation of tumor cells [71]. Moreover, low PH can also lead to tumor immunosuppression, reduce the sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapy drugs, and increase the drug resistance of tumor cells [72, 73].

Currently, most of the chemotherapeutic drugs used clinically are weakly alkaline (such as doxorubicin and mitonolone). Low PH can cause partial ionization of weakly alkaline drugs, prevent these drugs from entering cells and reduce the efficacy of these drugs, and lead to tumor cells to develop resistance to chemotherapy drugs [74–76]. Studies have shown that acidic environment can inhibit ATP-dependent active transport and reduce the absorption of methotrexate by cells [77, 78].

-

c.

Tumor immunosuppression is an important feature of tumor microenvironment [79, 80]: Tumor microenvironment contains a variety of immune cells (such as tumor-associated macrophages, T lymphocytes, NK cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells) [81–83]. These cells mean that the immune system has a certain immunosuppressive effect on the tumor, and it also means that the tumor has a certain immune escape effect on the immune system. T lymphocytes play an important role in immune escape and can be divided into two groups of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells have anti-tumor immunity [84, 85]. CD4+ T cells are mainly divided into helper T cells (Th) and regulatory T cells (Treg). Under normal circumstances, Th cells promote the functions of other immune cells such as B cells, CD8+ T cells, and phagocytes by secreting a variety of inflammatory factors [86, 87]. Conversely, Treg cells, as immune tolerant cells that prevent the immune system from attacking autologous organs, can inhibit the activation and proliferation of CD8+ T cells, B cells, NK cells, and antigen-presenting cells, and release inhibitory cytokines (IL-10) to promote tumor growth [88, 89]. Studies have shown that the accumulation of Treg cells in the tumor microenvironment can promote the progression and migration of tumor cells, and reduce survival prognosis [90, 91]. Moreover, tumor-associated macrophages promote tumor growth through anti-tumor immunity [92]. For example, studies have found that the activation of M1 macrophage increases the number of anti-tumor immune cells, reduces the infiltration of immunosuppressive cells, and enhances the ability of anti-tumor immunity [93]. Furthermore, NK cells achieve tumor immune escape through the conversion of immune killing. There are many types of inhibitory receptors for NK cells, such as KIRs, NKG2A, ILT-2, and PD-1. For example, KIRs binds to MHC-I to enhance the inhibitory signal transmission and block the activation of NK cells, and enhances tumor immune escape [94, 95]. Another immune escape is the transformation of dendritic cells into bone marrow-derived suppressor cells, thus playing an immunosuppressive role [96]. Studies have shown that bone marrow-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) inhibit immune cells survival and proliferation by inducing the release of IDOI, inducible nitric synthase (INOS), NO and reactive oxygen species (ROS), and consuming nutrients in the tumor microenvironment [44]. In addition, P2X7 receptor can activate immune cells (such as macrophages and lymphocytes), increase the expression of cytokines and chemokines (such as IL-1β, IL-8, MCP-1, and ROS), and regulate tumor progression [97–99]. Studies have shown that P2X7 receptor activation can enhance the expression of MCP-1, IL-8, and VEGF, and promote the growth of glioma cells [100]. Further studies have shown that P2X7 receptor activation can increase the expression of MIP-1 and MCP-1 in microglia and macrophages to promote the infiltration of glioma cells [101]. To sum up, inhibiting and reducing the activation and number of immunosuppressive cells, promoting the migration of immune cells into the tumor microenvironment, reducing the immune tolerance of tumor cells, and enhancing anti-tumor immunity can become immune targets for tumor therapy.

-

d.

Exocrine body: The exosomes produced by cells can regulate the body’s immune response and also contribute to the development of tumor cells [102, 103]. The main biological characteristic of exocrine body to promote tumor growth and proliferation is that exocrine body can interact with immune cells, endothelial cells, and tumor-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment, change the microenvironment before tumor metastasis, and promote tumor angiogenesis and contribute to tumor progression [104–106]. Studies have found that the exocrine body produced by cholangiocarcinoma cells can inhibit the activity of CD3+, CD8+, NK, CD56+, CD3+, and CD56+ cells and exert anti-tumor immunity [107]. Further research found that exo-PD-L1 can promote the progression of non-small cell lung cancer and is closely related to tumor size, lymph node metastasis, and TNM staging [108].

-

e.

Tumor-associated fibroblasts: CAFs-mediated immunosuppression is through the stimulation of transforming growth factor β on most cells, including two aspects: inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and increasing tumor cell activity [109–111]. Moreover, CAFs themselves also have immunosuppressive properties, which can upregulate the expression of histone deacetylase in cells through COX-2, resulting in immune escape [112]. Studies have shown that CD10+GPR77+CAFs provide survival basis for cancer stem cells, and promote tumor formation, and tumor cells are resistant to chemotherapy [113]. Furthermore, CAFs can also express a variety of specific markers (such as fibroblast activation protein (FAP), fibroblast-specific protein, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, and vimentin and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan) [109]. These markers are expressed differently in different tumor cells, which mean that CAFs have phenotypic heterogeneity.

Taken together, it is certain that the tumor microenvironment plays a decisive role in the development and fate of tumor cells. Therefore, improving the tumor microenvironment (such as reducing immunosuppression, increasing immune cell activation and proliferation, improving hypoxic and acidic environment, and inhibiting the release of tumor-related exocrine bodies) and can become the basis for anti-tumor therapy.

The role of ATP in tumor progression

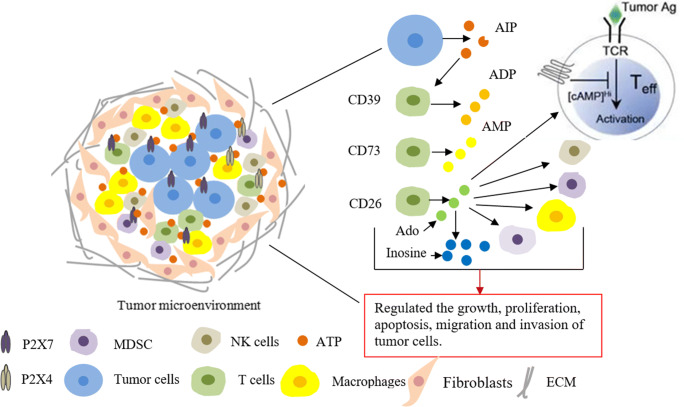

ATP is an important energy substance and also a key signal molecule, which is closely related to the survival, adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and migration of cells [114–116]. Under normal circumstances, the concentration of extracellular ATP is low, but when the body is in a pathological state, such as inflammation and immunity, the concentration of extracellular ATP increases sharply. Accordingly, in the process of tumorigenesis, a large amount of intracellular ATP is released into the extracellular matrix, which leads to a significant increase in the concentration of ATP in the tumor microenvironment. By interacting with other molecular substances (such as P2X purinergic receptors), it can regulate the progression and drug resistance of tumor cells [117, 118] (Fig. 1). Studies have found that reducing the release of ATP in non-small cell lung cancer cells can reduce the proliferation of cancer cells and induce cancer cell death [119]. Further studies have found that ATP and its metabolite (adenosine) can jointly inhibit the proliferation of cholangiocarcinoma [117]. Moreover, ATP can also act on immune cells in the microenvironment (such as macrophages and lymphocytes), phagocytose and kill apoptotic cells, and produce anti-tumor immunity and drug resistance [120, 121]. Studies have shown that human A549 lung cancer cells internalize extracellular ATP through swallowing, reduce the concentration of extracellular ATP, and develop resistance to anticancer drugs [122]. This possible mechanism is caused by the internalization of extracellular ATP by macrophages. Furthermore, chemotherapy drugs (such as cisplatin, doxorubicin, and mitomycin C) can reduce the concentration of ATP in the microenvironment and inhibit the phagocytosis and elimination of immune cells [123, 124]. In addition, ATP can be used as a drug delivery system to increase the efficacy of anticancer drugs [125]. Recent studies have found that nanocarriers are a therapeutic strategy for the delivery of anticancer drugs. The carrier can be cross-linked with ATP and encapsulate the chemotherapeutic drugs to deliver the drugs to tumor cells, while high concentration of ATP can trigger the release of chemotherapeutic drugs and improve the efficacy of anti-tumor treatment [126]. These data indicate that ATP has important significance in the regulation of the development of tumor cells and can be used as a potential target for tumor therapy, but the specific detailed mechanism needs to be further explored.

Fig. 1.

The internal correlation between ATP in tumor microenvironment and tumor. Tumor microenvironment contains a variety of components, such as tumor-associated macrophages, bone marrow-derived suppressor cells, T lymphocytes, fibroblasts, extracellular matrix, ATP, tumor cells, and growth factors. These components constitute the environment in which tumor cells depend on survival. ATP is secreted into the microenvironment through tumor cells and other cells, acts on immune cells (such as CD39, CD26, CD72 cells) and other molecular substances (such as P2X purinergic receptors), hydrolyzes into ADP, AMP, and adenosine, further acts on other immune cells (such as macrophages, NK cells, and dendritic cells), and exerts immune functions, thereby regulating the progression of tumor cells

The role of P2X purinergic receptors in tumors

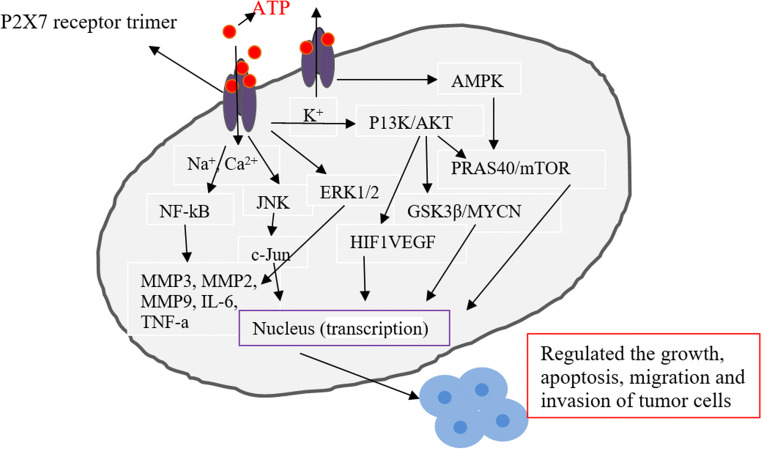

The role of P2X purinergic receptors in tumor progression has made some progress. P2X purinergic receptors activation or increased expression level can regulate the proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion of tumor cells [127]. In recent years, different studies have confirmed the role of P2X purinergic receptors in tumor progression [40]. In the P2X family, the P2X7 receptor plays a leading role in the development of tumors, and has also become a new target for exploring tumor treatment [128]. Recently, the excavation and exploration of the biological functions of P2X7 receptor have found that P2X7 receptor is expressed in most tumors, such as liver cancer [129], colorectal cancer [130], breast cancer [54], pancreatic cancer [131], prostate cancer [132], and neuroblastoma [133], which promotes or inhibits the development of tumors (Fig. 2). Indeed, activation of P2X7 receptor can promote the growth, proliferation, migration, and invasion of tumor cells. It has been found that high expression of P2X7 receptor can promote the growth and metastasis of human osteosarcoma cells through PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin and mTOR/HIF1α/VEGF signaling [134]. ATP-mediated P2X7 receptor activation regulates the expression of E-cadherin and MMP-13 through AKT signal, and promotes the growth and migration of breast cancer cells [135]. It was further found that high expression of P2X7 promoted the growth of colorectal cells, and that P2X7 receptor could be used as a biological indicator to evaluate the overall survival rate of patients with colorectal cancer [136]. These data mean that P2X7 receptor may become another potential biomarker for tumor evaluation. However, what is interesting is that acute exposure of tumor cells to ATP can cause rapid cytotoxic effects, which lead to inhibition of tumor growth [137]. Indeed, P2X7 receptor activation can also promote tumor cell apoptosis and death. Studies have shown that high levels of extracellular ATP can mediate P2X7-PI3K/AKT axis and P2X7-AMPK-PRAS40-mTOR axis to promote tumor cell death [138]. High level of eATP enhances the function of P2X7 receptor, increases the opening of the pores on the membrane, and promotes the death of colon cancer cells by regulating the downstream AKT/PRAS40/mTOR signal [139]. The possible reasons for the conflicting results of different studies are related to the degree of P2X7 receptor activation and the immune status in the tumor microenvironment. Moreover, another interesting finding is that P2X7 receptor can also promote tumor blood vessel formation [140]. For example, P2X7 receptor activation can promote tumor blood vessel growth and enhance neuroblastoma activity by activating PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/MYCN and AKT/HIF1VEGF axes [141]. The above data reveals the dual function of P2X7 receptor in regulating tumor progression. Therefore, P2X7 receptors can be considered potential targets for tumor therapy based on the ATP concentration and the degree of activation of P2X7 receptor. In addition, the effects of immune cells and inflammatory cells in the tumor microenvironment on the function of P2X7 receptors should also be considered.

Fig. 2.

Potential correlation between P2X7 receptor and tumor development. After tumorigenesis, cells (such as tumor cells and immune cells) release a large amount of ATP into the extracellular matrix, resulting in a sharp increase in ATP concentration, activating P2X7 receptor and opening ion channels on the cell membrane (sodium ions, calcium ions influx, and potassium ions outflow), activating intracellular signaling pathways (such as NF-kB, MAPK, mTOR, and JNK), and regulating gene transcription in the nucleus, thereby affecting the progression of tumor cells (promoting growth or inhibiting proliferation)

Another interesting P2X purinergic receptors is P2X4. P2X4 receptor indirectly regulates the progression of tumor cells mainly by mediating inflammation and immune cells in the microenvironment [137]. Studies have found that P2X4 receptor is highly expressed in glioma tissues and surrounding infiltrating tissues, and plays a role in regulating tumor cells by mediating tumor-related macrophages and microglia [142]. It has been found that upregulation of P2X4 (P2Y1 and P2X7) in non-small cell lung cancer promotes tumor invasion and metastasis by mediating inflammation and immune cells [143]. Recent studies have found that high expression of P2X4 (P2X7) in liver cancer tissues is related to the growth and proliferation of liver cancer. It is speculated that the possible reason is that the P2X4 (P2X7) receptor is closely related to the inflammation caused by cell stress [129]. Further research found that high expression of P2X4 receptor was detected in hepatitis C virus hepatocellular carcinoma, which was related to the growth of liver cancer. It is speculated that the possible cause is related to inflammation and immune response [144]. In addition, related studies have shown that the existence of multiple P2X purinergic receptors (P2X1, P2X3, P2X5, P2X6) has been identified in some tumor cells, but these receptors have no functional properties. However, studies have also shown that P2X5 is expressed in prostate cancer cells, and ATP can mediate P2X5 receptors to inhibit growth and migration of tumor cells [145–148]. Taken together, these data indicate that P2X purinergic receptors play an important regulatory role in tumor progression, indicating that P2X purinergic receptors can become a potential target for tumor treatment.

P2X purinergic receptors as a potential target for tumor therapy

Diversification of tumor therapy methods, including surgical treatment, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and gene therapy, improves the survival rate and cure rate of patients [149]. However, tumor metastasis, early recurrence, and resistance to postoperative radiotherapy and chemotherapy are still the main causes of death in patients with cancers [150]. Therefore, more in-depth exploration and mining of the relevant molecular mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis of tumors is needed, better targeted therapy, and improves tumor diagnosis rate and cure rate, and the development of new molecular targeted drugs to inhibit tumor progression has become an urgent problem to be solved today. Fortunately, research on the relationship between P2X purinergic receptors and tumors provided basic theoretical basis and support for anti-tumor therapy [151, 152].

As mentioned earlier, P2X purinergic receptors have a certain contribution to tumor progression. Therefore, inhibiting the activation of P2X purinergic receptors and reducing their expression level may become a new direction for tumor treatment. The development and use of P2X purinergic receptors antagonists are expected to become pharmacological targets for tumor suppression. In the early days, the use of P2X purinergic receptors antagonists was limited to broad-spectrum antagonists (such as TNP-ATP and PPADS), and these antagonists were used in the research of most diseases (such as pain, inflammation, and immune and cardiovascular diseases) [153–156]. However, different P2X subtypes have different affinities for broad-spectrum antagonists, resulting in greater differences in efficacy. For example, TNP-ATP has a higher effect on P2X1, P2X3, and P2X2/3 than the effect over P2X4 and P2X7. PPADS has an antagonist effect on some P2X1, P2X2, P2X3, and P2X5, but the inhibition of P2X4 is lower [157, 158]. In fact, P2X non-selective antagonists have a certain effect on the treatment of some diseases, but their pharmacological effects are lower than that of selective or specific antagonists. Especially for cancer, the use of P2X broad-spectrum antagonists is greatly restricted. Therefore, the use of selective antagonists or specific antagonists of different subtypes of P2X purinergic receptors has become the focus of research on tumor treatment.

P2X7 receptor is one of the most interesting anticancer targets among P2X purinergic receptors. P2X7 receptor involvement in tumor progression has been consistently recognized [17, 36, 159]. Therefore, downregulation of P2X7 expression can become a potential molecular target for tumor therapy [160–162]. Studies have shown that hyperthermia can enhance the function of P2X7 receptor, open the potentiating pores on the cell membrane, activate downstream AKT/PRAS40/mTOR signaling, and promote tumor cell apoptosis. While shRNA transfection of tumor cells to knock down P2X7 receptor expression can enhance tumor cell activity [139], siRNA transient knockdown of P2X7 receptor expression can inhibit the migration and metastasis of breast cancer cells via the AKT pathway [135]. Currently, some P2X7 receptor antagonists have made some progression in the application of cancer treatment [163, 164]. For example, P2X7 antagonist (KN-62) can reduce the expression of P2X7 receptor, downregulate the expression of ERK1/2 and JNK, and inhibit the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells [131]. Moreover, it is particularly gratifying that the development and use of P2X7 selective or specific antagonists (such as BBG, A74003, and AZ10606120) in tumor treatment have been expanded and applied [165–168]. For example, high-dose ATP (> 20 μm)-mediated P2X7 receptor activation has a strong inhibitory effect on the migration of human breast cancer vascular endothelial cells, while P2X7 receptor antagonist (BBG) can reverse the above phenomenon [169]. Studies have shown that P2X7 receptor activation promotes the proliferation, migration, and metastasis of osteosarcoma cells by activating PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin and mTOR/HIF1α/VEGF signals. While the use of P2X7 receptor antagonist (A740003) can inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells [134], further studies have shown that P2X7 receptor antagonists (AZ10606120 and A74003) which downregulate the expression of P2X7 receptor can inhibit the growth and metastasis of colon cancer cells [99]. Furthermore, some other antagonists (such as A-438079) downregulate the expression of P2X7 receptor and inhibit tumor progression [162, 170]. In addition, P2X7 receptor is also closely related to the overall survival rate of patients with tumors, lymph node metastasis, and TNM staging [171]. These data suggest a potential therapeutic role for P2X7 receptor antagonists.

In addition, P2X7 receptor is also closely related to cancer-induced pain (such as bone cancer pain), and P2X7 receptor antagonist (A839977) can effectively inhibit cancer-induced pain [172]. Although different studies have revealed that P2X7 receptor antagonists can be used in cancer treatment [173, 174], however, activation of P2X7 receptor can promote cell survival and induce cytotoxicity. And how these two opposing effects are controlled is not fully understood. Therefore, P2X7 receptor as the target of anticancer therapy, more research is needed to reveal the concentration of ATP used and grasp the degree of activation of P2X7 receptor. All in all, P2X7 receptor is expected to become a new pharmacological target for cancer treatment.

Conclusion

The molecular mechanism of the development of tumor is extremely complex, and its treatment is still the most difficult problem at present. Therefore, understanding and elucidating the molecular basis of cancer pathogenesis and finding new targets for tumor prevention and treatment is particularly important. Fortunately, the role of P2X purinergic receptors in tumor progression has made great progress. ATP-mediated activation of P2X purinergic receptors plays an important role in regulating the development and fate of tumor cells. Activation of P2X purinergic receptors can promote or inhibit the development of tumor cells. While the functions of P2X4 and P2X7 receptors are the most eye-catching, they can not only directly act on tumor cells but also indirectly regulate the development of tumors by mediating immune cells. Most studies have revealed that P2X purinergic receptors antagonists can inhibit their activation, reduce their expression level, and inhibit the progression of tumors. Therefore, the research and development of P2X-specific antagonists or selective antagonists for tumor treatment have great prospects and may become a new molecular pharmacological target for the treatment of tumors.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (20202BABL206163 and 20202BABL206091), the Graduate Student Innovation Fund Project of Jiangxi Province (YC2020-B047).

Compliance with ethical standards

Competing of interests

Wen-jun Zhang declares that he/she has no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tian X, Shen H, Li Z, Wang T, Wang S. Tumor-derived exosomes, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and tumor microenvironment. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:84. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0772-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ji K, Mayernik L, Moin K, Sloane BF. Acidosis and proteolysis in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019;38:103–112. doi: 10.1007/s10555-019-09796-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang S, Gao H. Nanoparticles for modulating tumor microenvironment to improve drug delivery and tumor therapy. Pharmacol Res. 2017;126:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubyak GR. Luciferase-assisted detection of extracellular ATP and ATP metabolites during immunogenic death of cancer cells. Methods Enzymol. 2019;629:81–102. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang WJ, Hu CG, Zhu ZM, et al. Effect of P2X7 receptor on tumorigenesis and its pharmacological properties. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;125:109844. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boison D, Yegutkin GG. Adenosine metabolism: emerging concepts for Cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2019;36:582–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aymeric L, Apetoh L, Ghiringhelli F, Tesniere A, Martins I, Kroemer G, Smyth MJ, Zitvogel L. Tumor cell death and ATP release prime dendritic cells and efficient anticancer immunity. Cancer Res. 2010;70:855–858. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Virgilio F, Sarti AC, Falzoni S, et al. Extracellular ATP and P2 purinergic signalling in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:601–618. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrell AW, Gadeock S, Pupovac A, et al. P2X7 receptor activation induces cell death and CD23 shedding in human RPMI 8226 multiple myeloma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1800;2010:1173–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnstock G, Knight GE. The potential of P2X7 receptors as a therapeutic target, including inflammation and tumour progression. Purinergic Signal. 2018;14:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11302-017-9593-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang WJ, Zhu ZM, Liu ZX. The role and pharmacological properties of the P2X7 receptor in neuropathic pain. Brain Res Bull. 2020;155:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen S, Feng W, Yang X, Yang W, Ru Y, Liao J, Wang L, Lin Y, Ren Q, Zheng G. Functional expression of P2X family receptors in macrophages is affected by microenvironment in mouse T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446:1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng L, Sun X, Csizmadia E, Han L, Bian S, Murakami T, Wang X, Robson SC, Wu Y. Vascular CD39/ENTPD1 directly promotes tumor cell growth by scavenging extracellular adenosine triphosphate. Neoplasia. 2011;13:206–216. doi: 10.1593/neo.101332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.North RA. P2X receptors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci. 2016;371:20150427. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burnstock G. P2X ion channel receptors and inflammation. Purinergic Signal. 2016;12:59–67. doi: 10.1007/s11302-015-9493-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawate T. P2X receptor activation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1051:55–69. doi: 10.1007/5584_2017_55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boldrini L, Giordano M, Alì G, Servadio A, Pelliccioni S, Niccoli C, Mussi A, Fontanini G. P2X7 protein expression and polymorphism in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Negat Results Biomed. 2014;13:16. doi: 10.1186/1477-5751-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Shukaili A, Al-Kaabi J, Hassan B, et al. P2X7 receptor gene polymorphism analysis in rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Immunogenet. 2011;38:389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313X.2011.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thunberg U, Tobin G, Johnson A, Söderberg O, Padyukov L, Hultdin M, Klareskog L, Enblad G, Sundström C, Roos G, Rosenquist R. Polymorphism in the P2X7 receptor gene and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Lancet. 2002;360:1935–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ralevic V. P2X receptors in the cardiovascular system and their potential as therapeutic targets in disease. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:851–865. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666141215094050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang WJ, Zhu ZM, Liu ZX. The role of P2X4 receptor in neuropathic pain and its pharmacological properties. Pharmacol Res. 2020;158:104875. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jørgensen NR, Syberg S, Ellegaard M. The role of P2X receptors in bone biology. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:902–914. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666141215094749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmid R, Evans RJ. ATP-gated P2X receptor channels: molecular insights into functional roles. Annu Rev Physiol. 2019;81:43–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020518-114259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hattori M, Gouaux E. Molecular mechanism of ATP binding and ion channel activation in P2X receptors. Nature. 2012;485:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nature11010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duan S, Neary JT. P2X(7) receptors: properties and relevance to CNS function. Glia. 2006;54:738–746. doi: 10.1002/glia.20397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan Z, Li S, Liang Z, Tomić M, Stojilkovic SS. The P2X7 receptor channel pore dilates under physiological ion conditions. J Gen Physiol. 2008;132:563–573. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winkelmann VE, Thompson KE, Neuland K, Jaramillo AM, Fois G, Schmidt H, Wittekindt OH, Han W, Tuvim MJ, Dickey BF, Dietl P, Frick M. Inflammation-induced upregulation of P2X4expression augments mucin secretion in airway epithelia. Am J Phys Lung Cell Mol Phys. 2019;316:L58–L70. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00157.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Virgilio F. P2X receptors and inflammation. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:866–877. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666141210155311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling and neurological diseases: an update. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2017;16:257–265. doi: 10.2174/1871527315666160922104848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soto F, Garcia-Guzman M, Gomez-Hernandez JM, Hollmann M, Karschin C, Stuhmer W. P2X4: an ATP-activated ionotropic receptor cloned from rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3684–3688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He Y, Taylor N, Fourgeaud L, Bhattacharya A. The role of microglial P2X7: modulation of cell death and cytokine release. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:135. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0904-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bele T, Fabbretti E. P2X receptors, sensory neurons and pain. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:845–850. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666141011195351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burnstock G. Physiopathological roles of P2X receptors in the central nervous system. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:819–844. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666140706130415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee HY, Bardini M, Burnstock G. Distribution of P2X receptors in the urinary bladder and the ureter of the rat. J Urol. 2000;163:2002–2007. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gever JR, Cockayne DA, Dillon MP, Burnstock G, Ford APDW. Pharmacology of P2X channels. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452:513–537. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bae JY, Lee SW, Shin YH, Lee JH, Jahng JW, Park K. P2X7 receptor and NLRP3 Inflammasome activation in head and neck cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:48972–48982. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hope JM, Greenlee JD, King MR. Mechanosensitive ion channels: TRPV4 and P2X7 in disseminating cancer cells. Cancer J. 2018;24:84–92. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jeong S, Zheng B, Wang H, et al. Nervous system and primary liver cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1869;2018:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hevia MJ, Castro P, Pinto K, Reyna-Jeldes M, Rodríguez-Tirado F, Robles-Planells C, Ramírez-Rivera S, Madariaga JA, Gutierrez F, López J, Barra M, de la Fuente-Ortega E, Bernal G, Coddou C. Differential effects of purinergic signaling in gastric cancer-derived cells through P2Y and P2X receptors. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:612. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adinolfi E, Capece M, Amoroso F, Marchi E, Franceschini A. Emerging roles of P2X receptors in cancer. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:878–890. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666141012172913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koch-Nolte F, Eichhoff A, Pinto-Espinoza C, Schwarz N, Schäfer T, Menzel S, Haag F, Demeules M, Gondé H, Adriouch S. Novel biologics targeting the P2X7 ion channel. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2019;47:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stokes L, Layhadi JA, Bibic L, Dhuna K, Fountain SJ. P2X4 receptor function in the nervous system and current breakthroughs in pharmacology. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:291. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blanc C, Hans S, Tran T, Granier C, Saldman A, Anson M, Oudard S, Tartour E. Targeting resident memory T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1722. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar V, Patel S, Tcyganov E, Gabrilovich DI. The nature of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:208–220. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Denton AE, Roberts EW, Fearon DT. Stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1060:99–114. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-78127-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Danai LV, Babic A, Rosenthal MH, Dennstedt EA, Muir A, Lien EC, Mayers JR, Tai K, Lau AN, Jones-Sali P, Prado CM, Petersen GM, Takahashi N, Sugimoto M, Yeh JJ, Lopez N, Bardeesy N, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Liss AS, Koong AC, Bui J, Yuan C, Welch MW, Brais LK, Kulke MH, Dennis C, Clish CB, Wolpin BM, Vander Heiden MG. Altered exocrine function can drive adipose wasting in early pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2018;558:600–604. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0235-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broers JL, Ramaekers FC. The role of the nuclear lamina in cancer and apoptosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;773:27–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-8032-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vlasova-St Louis I, Bohjanen PR. Post-transcriptional regulation of cytokine and growth factor signaling in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2017;33:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim J, Bae JS. Tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils in tumor microenvironment. Mediat Inflamm. 2016;2016:6058147. doi: 10.1155/2016/6058147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arneth B. Tumor Microenvironment. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;56:15. doi: 10.3390/medicina56010015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hinshaw DC, Shevde LA. The tumor microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2019;79:4557–4566. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asiaf A, Ahmad ST, Arjumand W, Zargar MA. MicroRNAs in breast cancer: diagnostic and therapeutic potential. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1699:23–43. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7435-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boldrini L, Giordano M, Alì G, Melfi F, Romano G, Lucchi M, Fontanini G. P2X7 mRNA expression in non-small cell lung cancer: MicroRNA regulation and prognostic value. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(1):449–453. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang S, Chen Y, Wu W, Ouyang N, Chen J, Li H, Liu X, Su F, Lin L, Yao Y. miR-150 promotes human breast cancer growth and malignant behavior by targeting the pro-apoptotic purinergic P2X7 receptor. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng L, Zhang X, Yang F, Zhu J, Zhou P, Yu F, Hou L, Xiao L, He Q, Wang B. Regulation of the P2X7R by microRNA-216b in human breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;452:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.07.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jelassi B, Chantôme A, Alcaraz-Pérez F, Baroja-Mazo A, Cayuela ML, Pelegrin P, Surprenant A, Roger S. P2X(7) receptor activation enhances SK3 channels- and cystein cathepsin-dependent cancer cells invasiveness. Oncogene. 2011;30(18):2108–2122. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fu W, McCormick T, Qi X, Luo L, Zhou L, Li X, Wang BC, Gibbons HE, Abdul-Karim FW, Gorodeski GI. Activation of P2X(7)-mediated apoptosis inhibits DMBA/TPA-induced formation of skin papillomas and cancer in mice. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang Y, Lin D, Taniguchi CM. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) in the tumor microenvironment: friend or foe? Sci China Life Sci. 2017;60:1114–1124. doi: 10.1007/s11427-017-9178-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parks SK, Cormerais Y, Pouysségur J. Hypoxia and cellular metabolism in tumour pathophysiology. J Physiol. 2017;595:2439–2450. doi: 10.1113/JP273309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ni C, Ma P, Qu L, Wu F, Hao J, Wang R, Lu Y, Yang W, Erben U, Qin Z. Accelerated tumour metastasis due to interferon-γ receptor-mediated dissociation of perivascular cells from blood vessels. J Pathol. 2017;242:334–346. doi: 10.1002/path.4907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Casola S, Perucho L, Tripodo C, Sindaco P, Ponzoni M, Facchetti F. The B-cell receptor in control of tumor B-cell fitness: biology and clinical relevance. Immunol Rev. 2019;288:198–213. doi: 10.1111/imr.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hajizadeh F, Okoye I, Esmaily M, Ghasemi Chaleshtari M, Masjedi A, Azizi G, Irandoust M, Ghalamfarsa G, Jadidi-Niaragh F. Hypoxia inducible factors in the tumor microenvironment as therapeutic targets of cancer stem cells. Life Sci. 2019;237:116952. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joseph JP, Harishankar MK, Pillai AA, Devi A. Hypoxia induced EMT: a review on the mechanism of tumor progression and metastasis in OSCC. Oral Oncol. 2018;80:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tong WW, Tong GH, Liu Y. Cancer stem cells and hypoxia-inducible factors (review) Int J Oncol. 2018;53:469–476. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koka P, Mundre RS, Rangarajan R, Chandramohan Y, Subramanian RK, Dhanasekaran A. Uncoupling Warburg effect and stemness in CD133+ve cancer stem cells from Saos-2 (osteosarcoma) cell line under hypoxia. Mol Biol Rep. 2018;45:1653–1662. doi: 10.1007/s11033-018-4309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Albuquerque APB, Balmaña M, Mereiter S, Pinto F, Reis CA, Beltrão EIC. Hypoxia and serum deprivation induces glycan alterations in triple negative breast cancer cells. Biol Chem. 2018;399:661–672. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2018-0121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lu J, Tan M, Cai Q. The Warburg effect in tumor progression: mitochondrial oxidative metabolism as an anti-metastasis mechanism. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiao H, Li TK, Yang JM, Liu LF. Acidic pH induces topoisomerase II-mediated DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5205–3210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0935978100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brisson L, Reshkin SJ, Goré J, Roger S. pH regulators in invadosomal functioning: proton delivery for matrix tasting. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:847–860. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.García-Venzor A, Mandujano-Tinoco EA, Lizarraga F, Zampedri C, Krötzsch E, Salgado RM, Dávila-Borja VM, Encarnación-Guevara S, Melendez-Zajgla J, Maldonado V. Microenvironment-regulated lncRNA-HAL is able to promote stemness in breast cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta, Mol Cell Res. 2019;1866:118523. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2019.118523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Riemann A, Reime S, Thews O. Hypoxia-related tumor acidosis affects MicroRNA expression pattern in prostate and breast tumor cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;977:119–124. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-55231-6_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Humbert M, Guery L, Brighouse D, Lemeille S, Hugues S. Intratumoral CpG-B promotes antitumoral neutrophil, cDC, and T-cell cooperation without reprograming tolerogenic pDC. Cancer Res. 2018;78:3280–3292. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu YX. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/ni.2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ali I, Alfarouk KO, Reshkin SJ, Ibrahim ME. Doxycycline as potential anti-cancer agent. Anti Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2017;17:1617–1623. doi: 10.2174/1871520617666170213111951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang Y, Dang M, Tian Y, Zhu Y, Liu W, Tian W, Su Y, Ni Q, Xu C, Lu N, Tao J, Li Y, Zhao S, Zhao Y, Yang Z, Sun L, Teng Z, Lu G. Tumor acidic microenvironment targeted drug delivery based on pHLIP-modified mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:30543–30552. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b10840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hu CF, Huang YY, Wang YJ, et al. Upregulation of ABCG2 via the PI3K-Akt pathway contributes to acidic microenvironment-induced cisplatin resistance in A549 and LTEP-a-2 lung cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2016;36:455–461. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Monti D, Tampucci S, Zucchetti E, Granchi C, Minutolo F, Piras AM. Effect of tumor relevant acidic environment in the interaction of a N-hydroxyindole-2-carboxylic derivative with the phospholipid bilayer. Pharm Res. 2018;35:175. doi: 10.1007/s11095-018-2449-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim SR, Kim EH. Effects of chronic exposure to acidic environment on the response of tumor cells to radiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2016;92:502–507. doi: 10.1080/09553002.2016.1206222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Egelston CA, Avalos C, Tu TY, et al. Resident memory CD8+ T cells within cancer islands mediate survival in breast cancer patients. JCI Insight. 2019;4:130000. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.130000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ferrari SM, Fallahi P, Galdiero MR, et al. Immune and inflammatory cells in thyroid cancer microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:E4413. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Alissafi T, Hatzioannou A, Legaki AI, Varveri A, Verginis P. Balancing cancer immunotherapy and immune-related adverse events: the emerging role of regulatory T cells. J Autoimmun. 2019;104:102310. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.102310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang W, Green M, Choi JE, Gijón M, Kennedy PD, Johnson JK, Liao P, Lang X, Kryczek I, Sell A, Xia H, Zhou J, Li G, Li J, Li W, Wei S, Vatan L, Zhang H, Szeliga W, Gu W, Liu R, Lawrence TS, Lamb C, Tanno Y, Cieslik M, Stone E, Georgiou G, Chan TA, Chinnaiyan A, Zou W. CD8+ T cells regulate tumour ferroptosis during cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 2019;569:270–274. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1170-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Duong MN, Erdes E, Hebeisen M, Rufer N. Chronic TCR-MHC (self)-interactions limit the functional potential of TCR affinity-increased CD8 T lymphocytes. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:284. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0773-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kishton RJ, Sukumar M, Restifo NP. Metabolic regulation of T cell longevity and function in tumor immunotherapy. Cell Metab. 2017;26:94–109. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ostroumov D, Fekete-Drimusz N, Saborowski M, Kühnel F, Woller N. CD4 and CD8 T lymphocyte interplay in controlling tumor growth. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018;75:689–713. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2686-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rangarajan S, Mariuzza RA. T cell receptor bias for MHC: co-evolution or co-receptors? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:3059–3068. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1600-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.DeWitt WS, 3rd, Smith A, Schoch G, et al. Human T cell receptor occurrence patterns encode immune history, genetic background, and receptor specificity. Elife. 2018;7:e38358. doi: 10.7554/eLife.38358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wing JB, Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Human FOXP3+ regulatory T cell heterogeneity and function in autoimmunity and cancer. Immunity. 2019;50:302–316. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Cell Res. 2017;27:109–118. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mpakou VE, Ioannidou HD, Konsta E, Vikentiou M, Spathis A, Kontsioti F, Kontos CK, Velentzas AD, Papageorgiou S, Vasilatou D, Gkontopoulos K, Glezou I, Stavroulaki G, Mpazani E, Kokkori S, Kyriakou E, Karakitsos P, Dimitriadis G, Pappa V. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of regulatory T cells in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Res. 2017;60:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2017.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zahran AM, Mohammed Saleh MF, Sayed MM, Rayan A, Ali AM, Hetta HF. Up-regulation of regulatory T cells, CD200 and TIM3 expression in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Biomark. 2018;22:587–595. doi: 10.3233/CBM-181368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:399–416. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zong S, Li J, Ye Z, et al. Lachnum polysaccharide suppresses S180 sarcoma by boosting anti-tumor immune responses and skewing tumor-associated macrophages toward M1 phenotype. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;S0141-8130:36746–36747. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Valipour B, Velaei K, Abedelahi A, Karimipour M, Darabi M, Charoudeh HN. NK cells: an attractive candidate for cancer therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:19352–19365. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shimasaki N, Jain A, Campana D. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19:200–218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Groth C, Hu X, Weber R, et al. Immunosuppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) during tumour progression. Br J Cancer. 2019;120:16–25. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0333-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bianchi G, Vuerich M, Pellegatti P, Marimpietri D, Emionite L, Marigo I, Bronte V, Di Virgilio F, Pistoia V, Raffaghello L. ATP/P2X7 axis modulates myeloid-derived suppressor cell functions in neuroblastoma microenvironment. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1135. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yao M, Fan X, Yuan B, Takagi N, Liu S, Han X, Ren J, Liu J. Berberine inhibits NLRP3 Inflammasome pathway in human triple-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cell. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19:216. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2615-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Adinolfi E, Capece M, Franceschini A, Falzoni S, Giuliani AL, Rotondo A, Sarti AC, Bonora M, Syberg S, Corigliano D, Pinton P, Jorgensen NR, Abelli L, Emionite L, Raffaghello L, Pistoia V, Di Virgilio F. Accelerated tumor progression in mice lacking the ATP receptor P2X7. Cancer Res. 2015;75:635–644. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wei W, Ryu JK, Choi HB, McLarnon JG. Expression and function of the P2X(7) receptor in rat C6 glioma cells. Cancer Lett. 2008;260:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fang KM, Wang YL, Huang MC, Sun SH, Cheng H, Tzeng SF. Expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in glioma-infiltrating microglia: involvement of ATP and P2X7 receptor. J Neurosci Res. 2018;89:199–211. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kalluri R. The biology and function of exosomes in cancer. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:1208–1215. doi: 10.1172/JCI81135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Whiteside TL. Tumor-derived exosomes and their role in cancer progression. Adv Clin Chem. 2016;74:103–141. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhao C, Gao F, Weng S, Liu Q. Pancreatic cancer and associated exosomes. Cancer Biomark. 2017;20:357–367. doi: 10.3233/CBM-170258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Greening DW, Gopal SK, Xu R, Simpson RJ, Chen W. Exosomes and their roles in immune regulation and cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2015;40:72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang L, Yu D. Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis, and immunity. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1871;2019:455–468. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen JH, Xiang JY, Ding GP, Cao LP. Cholangiocarcinoma-derived exosomes inhibit the antitumor activity of cytokine-induced killer cells by down-regulating the secretion of tumor necrosis factor-α and perforin. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2016;17:537–544. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1500266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li C, Li C, Zhi C, et al. Clinical significance of PD-L1 expression in serum-derived exosomes in NSCLC patients. J Transl Med. 2019;17:355. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-2101-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kalluri R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:582–598. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cho H, Seo Y, Loke KM, Kim SW, Oh SM, Kim JH, Soh J, Kim HS, Lee H, Kim J, Min JJ, Jung DW, Williams DR. Cancer-stimulated CAFs enhance monocyte differentiation and protumoral TAM activation via IL6 and GM-CSF secretion. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:5407–5421. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kobayashi H, Enomoto A, Woods SL, Burt AD, Takahashi M, Worthley DL, Takahashi M, Worthley DL. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in gastrointestinal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:282–295. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hashemi Goradel N, Najafi M, Salehi E, Farhood B, Mortezaee K. Cyclooxygenase-2 in cancer: a review. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:5683–5699. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Su S, Chen J, Yao H, et al. CD10+GPR77+cancer-associated fibroblasts promote cancer formation and chemoresistance by sustaining cancer stemness. Cell. 2018;172:841–856.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rivera A, Vanzulli I, Butt AM. A central role for ATP signalling in glial interactions in the CNS. Curr Drug Targets. 2016;17:1829–1833. doi: 10.2174/1389450117666160711154529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Salewskij K, Rieger B, Hager F, et al. The spatio-temporal organization of mitochondrial F1FO ATP synthase in cristae depends on its activity mode. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 2019;26:148091. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2019.148091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Meurer F, Do HT, Sadowski G, Held C. Standard Gibbs energy of metabolic reactions: II. Glucose-6-phosphatase reaction and ATP hydrolysis. Biophys Chem. 2017;223:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lertsuwan J, Ruchirawat M. Inhibitory effects of ATP and adenosine on cholangiocarcinoma cell proliferation and motility. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:3553–3561. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.11345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lee PJ, Woo SJ, Yoo HM, et al. Differential mechanism of ATP production occurs in response to succinylacetone in colon cancer cells. Molecules. 2019;24:E3575. doi: 10.3390/molecules24193575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Dai K, Radin DP, Leonardi D, et al. PINK1 depletion sensitizes non-small cell lung cancer to glycolytic inhibitor 3-bromopyruvate: involvement of ROS and mitophagy. Pharmacol Rep. 2019;71:1184–1189. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Krysko DV, Garg AD, Kaczmarek A, Krysko O, Agostinis P, Vandenabeele P. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:860–875. doi: 10.1038/nrc3380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sagar V, Vatapalli R, Lysy B, Pamarthy S, Anker JF, Rodriguez Y, Han H, Unno K, Stadler WM, Catalona WJ, Hussain M, Gill PS, Abdulkadir SA. EPHB4 inhibition activates ER stress to promote immunogenic cell death of prostate cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:801. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2042-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Qian Y, Wang X, Liu Y, Li Y, Colvin RA, Tong L, Wu S, Chen X. Extracellular ATP is internalized by macropinocytosis and induces intracellular ATP increase and drug resistance in cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2014;351:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Martins I, Tesniere A, Kepp O, Michaud M, Schlemmer F, Senovilla L, Séror C, Métivier D, Perfettini JL, Zitvogel L, Kroemer G. Chemotherapy induces ATP release from tumor cells. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:3723–5728. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.22.10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Qian C, Chen Y, Zhu S, Yu J, Zhang L, Feng P, Tang X, Hu Q, Sun W, Lu Y, Xiao X, Shen QD, Gu Z. ATP-responsive and near-infrared-emissive nanocarriers for anticancer drug delivery and real-time imaging. Theranostics. 2016;6:1053–1064. doi: 10.7150/thno.14843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mo R, Jiang T, DiSanto R, Tai W, Gu Z. ATP-triggered anticancer drug delivery. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3364. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wang GH, Huang GL, Zhao Y, Pu XX, Li T, Deng JJ, Lin JT. ATP triggered drug release and DNA co-delivery systems based on ATP responsive aptamers and polyethylenimine complexes. J Mater Chem B. 2016;4:3832–3841. doi: 10.1039/C5TB02764K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Roger S, Jelassi B, Couillin I, et al. Understanding the roles of the P2X7 receptor in solid tumour progression and therapeutic perspectives. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1848;2015:2584–2602. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Gorodeski GI. P2X7-mediated chemoprevention of epithelial cancers. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:1313–1332. doi: 10.1517/14728220903277249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Asif A, Khalid M, Manzoor S, Ahmad H, Rehman AU. Role of purinergic receptors in hepatobiliary carcinoma in Pakistani population: an approach towards proinflammatory role of P2X4 and P2X7 receptors. Purinergic Signal. 2019;15:367–374. doi: 10.1007/s11302-019-09675-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zhang Y, Ding J, Wang L. The role of P2X7 receptor in prognosis and metastasis of colorectal cancer. Adv Med Sci. 2019;64:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Choi JH, Ji YG, Ko JJ, Cho HJ, Lee DH. Activating P2X7 receptors increases proliferation of human pancreatic cancer cells via ERK1/2 and JNK. Pancreas. 2018;47:643–651. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Qiu Y, Li WH, Zhang HQ, et al. 2015 P2X7 mediates ATP-driven invasiveness in prostate cancer cells [published correction appears in PLoS One. 10:e0123388] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 133.Sun SH. Roles of P2X7 receptor in glial and neuroblastoma cells: the therapeutic potential of P2X7 receptor antagonists. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;41:351–355. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zhang Y, Cheng H, Li W, Wu H, Yang Y. Highly-expressed P2X7 receptor promotes growth and metastasis of human HOS/MNNG osteosarcoma cells via PI3K/Akt/GSK3β/β-catenin and mTOR/HIF1α/VEGF signaling. Int J Cancer. 2019;145:1068–1082. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Xia J, Yu X, Tang L, et al. P2X7 receptor stimulates breast cancer cell invasion and migration via the AKT pathway. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:103–110. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Qian F, Xiao J, Hu B, Sun N, Yin W, Zhu J. High expression of P2X7R is an independent postoperative indicator of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol. 2017;64:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Draganov D, Gopalakrishna-Pillai S, Chen YR, Zuckerman N, Moeller S, Wang C, Ann D, Lee PP. Modulation of P2X4/P2X7/Pannexin-1 sensitivity to extracellular ATP via Ivermectin induces a non-apoptotic and inflammatory form of cancer cell death. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16222. doi: 10.1038/srep16222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bian S, Sun X, Bai A, Zhang C, Li L, Enjyoji K, Junger WG, Robson SC, Wu Y. P2X7 integrates PI3K/AKT and AMPK-PRAS40-mTOR signaling pathways to mediate tumor cell death. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.de Andrade MP, Bian S, Savio LEB, et al. Hyperthermia and associated changes in membrane fluidity potentiate P2X7 activation to promote tumor cell death. Oncotarget. 2017;8:67254–67268. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Solini A, Simeon V, Derosa L, Orlandi P, Rossi C, Fontana A, Galli L, di Desidero T, Fioravanti A, Lucchesi S, Coltelli L, Ginocchi L, Allegrini G, Danesi R, Falcone A, Bocci G. Genetic interaction of P2X7 receptor and VEGFR-2 polymorphisms identifies a favorable prognostic profile in prostate cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2015;6:28743–28754. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Amoroso F, Capece M, Rotondo A, Cangelosi D, Ferracin M, Franceschini A, Raffaghello L, Pistoia V, Varesio L, Adinolfi E. The P2X7 receptor is a key modulator of the PI3K/GSK3β/VEGF signaling network: evidence in experimental neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2015;34:5240–5251. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Guo LH, Trautmann K, Schluesener HJ. Expression of P2X4 receptor in rat C6 glioma by tumor-associated macrophages and activated microglia. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;152:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Schmid S, Kübler M, Korcan Ayata C, Lazar Z, Haager B, Hoßfeld M, Meyer A, Cicko S, Elze M, Wiesemann S, Zissel G, Passlick B, Idzko M. Altered purinergic signaling in the tumor associated immunologic microenvironment in metastasized non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2015;90:516–521. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Khalid M, Manzoor S, Ahmad H, Asif A, Bangash TA, Latif A, Jaleel S. Purinoceptor expression in hepatocellular virus (HCV)-induced and non-HCV hepatocellular carcinoma: an insight into the proviral role of the P2X4 receptor. Mol Biol Rep. 2018;45:2625–2630. doi: 10.1007/s11033-018-4432-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Gómez-Villafuertes R, del Puerto A, Díaz-Hernández M, Bustillo D, Díaz-Hernández JI, Huerta PG, Artalejo AR, Garrido JJ, Miras-Portugal MT. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II signalling cascade mediates P2X7 receptor-dependent inhibition of neuritogenesis in neuroblastoma cells. FEBS J. 2009;276:5307–5325. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Azimi I, Beilby H, Davis FM, Marcial DL, Kenny PA, Thompson EW, Roberts-Thomson SJ, Monteith GR. Altered purinergic receptor-Ca2+ signaling associated with hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells. Mol Oncol. 2016;10:166–178. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Coutinho-Silva R, Stahl L, Cheung KK, de Campos NE, de Oliveira Souza C, Ojcius DM, Burnstock G. P2X and P2Y purinergic receptors on human intestinal epithelial carcinoma cells: effects of extracellular nucleotides on apoptosis and cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1024–G1035. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00211.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Shabbir M, Ryten M, Thompson C, Mikhailidis D, Burnstock G. Purinergic receptor-mediated effects of ATP in high-grade bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2008;101:106–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Khan M, Spicer J. The evolving landscape of cancer therapeutics. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2019;260:43–79. doi: 10.1007/164_2019_312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Roland NJ, Bradley PJ. The role of surgery in the palliation of head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;22:101–108. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Nörenberg W, Plötz T, Sobottka H, Chubanov V, Mittermeier L, Kalwa H, Aigner A, Schaefer M. TRPM7 is a molecular substrate of ATP-evoked P2X7-like currents in tumor cells. J Gen Physiol. 2016;147:467–483. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201611595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Mistafa O, Stenius U. Statins inhibit Akt/PKB signaling via P2X7 receptor in pancreatic cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:1115–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Tsuzuki K, Ase A, Séguéla P, Nakatsuka T, Wang CY, She JX, Gu JG. TNP-ATP-resistant P2X ionic current on the central terminals and somata of rat primary sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:3235–3242. doi: 10.1152/jn.01171.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Cho JH, Jung KY, Jung Y, Kim MH, Ko H, Park CS, Kim YC. Design and synthesis of potent and selective P2X3 receptor antagonists derived from PPADS as potential pain modulators. Eur J Med Chem. 2013;70:811–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Chen K, Zhang J, Zhang W, Zhang J, Yang J, Li K, He Y. ATP-P2X4 signaling mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation: a novel pathway of diabetic nephropathy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:932–943. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Lämmer AB, Beck A, Grummich B, Förschler A, Krügel T, Kahn T, Schneider D, Illes P, Franke H, Krügel U. The P2 receptor antagonist PPADS supports recovery from experimental stroke in vivo. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Liñán-Rico A, Wunderlich JE, Enneking JT, Tso DR, Grants I, Williams KC, Otey A, Michel K, Schemann M, Needleman B, Harzman A, Christofi FL. Neuropharmacology of purinergic receptors in human submucous plexus: involvement of P2X1, P2X2, P2X3 channels, P2Y and A3 metabotropic receptors in neurotransmission. Neuropharmacology. 2015;95:83–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Lambertucci C, Dal Ben D, Buccioni M, et al. Medicinal chemistry of P2X receptors: agonists and orthosteric antagonists. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:915–928. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666141215093513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Salaro E, Rambaldi A, Falzoni S, Amoroso FS, Franceschini A, Sarti AC, Bonora M, Cavazzini F, Rigolin GM, Ciccone M, Audrito V, Deaglio S, Pelegrin P, Pinton P, Cuneo A, di Virgilio F. Involvement of the P2X7-NLRP3 axis in leukemic cell proliferation and death. Sci Rep. 2016;6:26280. doi: 10.1038/srep26280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.De Marchi E, Orioli E, Pegoraro A, et al. The P2X7 receptor modulates immune cells infiltration, ectonucleotidases expression and extracellular ATP levels in the tumor microenvironment. Oncogene. 2019;38:3636–3650. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0684-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Adinolfi E, Raffaghello L, Giuliani AL, Cavazzini L, Capece M, Chiozzi P, Bianchi G, Kroemer G, Pistoia V, di Virgilio F. Expression of P2X7 receptor increases in vivo tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2957–2969. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Hofman P, Cherfils-Vicini J, Bazin M, Ilie M, Juhel T, Hebuterne X, Gilson E, Schmid-Alliana A, Boyer O, Adriouch S, Vouret-Craviari V. Genetic and pharmacological inactivation of the purinergic P2RX7 receptor dampens inflammation but increases tumor incidence in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Res. 2015;75:835–845. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Brisson L, Chadet S, Lopez-Charcas O, et al. P2X7 receptor promotes mouse mammary cancer cell invasiveness and tumour progression, and is a target for anticancer treatment. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:E2342. doi: 10.3390/cancers12092342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Ghalali A, Wiklund F, Zheng H, Stenius U, Högberg J. Atorvastatin prevents ATP-driven invasiveness via P2X7 and EHBP1 signaling in PTEN-expressing prostate cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:1547–1555. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Takai E, Tsukimoto M, Harada H, Kojima S. Autocrine signaling via release of ATP and activation of P2X7 receptor influences motile activity of human lung cancer cells. Purinergic Signal. 2014;10:487–497. doi: 10.1007/s11302-014-9411-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Park JH, Williams DR, Lee JH, Lee SD, Lee JH, Ko H, Lee GE, Kim S, Lee JM, Abdelrahman A, Müller CE, Jung DW, Kim YC. Potent suppressive effects of 1-piperidinylimidazole based novel P2X7 receptor antagonists on cancer cell migration and invasion. J Med Chem. 2016;59:7410–7430. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Vázquez-Cuevas FG, Martínez-Ramírez AS, Robles-Martínez L, Garay E, García-Carrancá A, Pérez-Montiel D, Castañeda-García C, Arellano RO. Paracrine stimulation of P2X7 receptor by ATP activates a proliferative pathway in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:1955–1966. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Zhang X, Meng L, He B, et al. The role of P2X7 receptor in ATP-mediated human leukemia cell death: calcium influx-independent. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin Shanghai. 2009;41:362–369. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Avanzato D, Genova T, Fiorio Pla A, et al. 2016 Activation of P2X7 and P2Y11 purinergic receptors inhibits migration and normalizes tumor-derived endothelial cells via cAMP signaling [published correction appears in Sci Rep. 2016 Nov 11;6:35897]. Sci Rep. 6:32602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 170.Schneider G, Glaser T, Lameu C, Abdelbaset-Ismail A, Sellers ZP, Moniuszko M, Ulrich H, Ratajczak MZ. Extracellular nucleotides as novel, underappreciated pro-metastatic factors that stimulate purinergic signaling in human lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:201. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0469-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]