Abstract

Geoffrey Burnstock will be remembered as the scientist who set up an entirely new field of intercellular communication, signaling via nucleotides. The signaling cascades involved in purinergic signaling include intracellular storage of nucleotides, nucleotide release, extracellular hydrolysis, and the effect of the released compounds or their hydrolysis products on target tissues via specific receptor systems. In this context ectonucleotidases play several roles. They inactivate released and physiologically active nucleotides, produce physiologically active hydrolysis products, and facilitate nucleoside recycling. This review briefly highlights the development of our knowledge of two types of enzymes involved in extracellular nucleotide hydrolysis and thus purinergic signaling, the ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases, and ecto-5′-nucleotidase.

Keywords: Adenosine, ATP, Ecto-5′-nucleotidase, E-NTPDase, Geoffrey Burnstock, History

Introduction

Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (E-NTPDases) and ecto-5′-nucleotidase (eN) are only part of a broader spectrum of extracellular nucleotide-metabolizing enzymes, including ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterases, alkaline phosphatases, prostatic acid phosphatase, or extracellular ATP-regenerating enzymes [1, 2]. Yet, E-NTPDases and eN have been the enzyme axis most extensively studied regarding purinergic signaling. Geoff Burnstock maintained great interest in the mechanisms of extracellular nucleotide breakdown as these control purinergic receptor activity. This brief review is dedicated to Geoffrey Burnstock (1929–2020) as the leading scientist and promotor in the field, founder and chief editor of this journal, wonderful colleague, and friend.

Nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases

Early studies

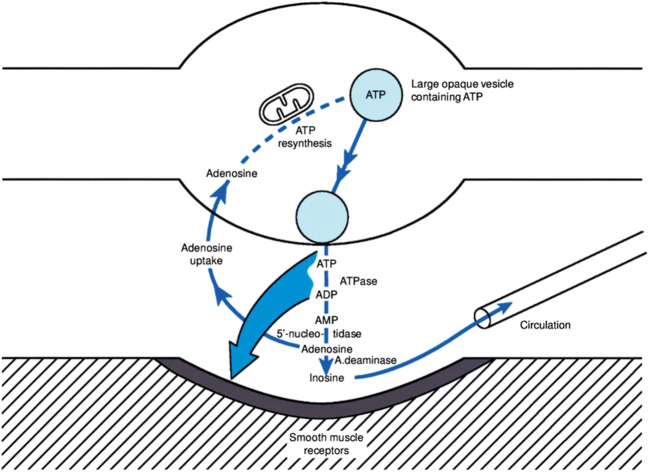

Regarding the fate of ATP released from nerve endings, Geoff Burnstock, in his seminal review of 1972 [3], discards the possibility that it can directly be recycled. He strongly supports the notion that it is broken down by extracellularly located enzymes via ADP and AMP to adenosine, which is then recycled into the nerve ending for intracellular resynthesis of ATP. He develops a model of synthesis, storage, release, and inactivation of ATP at the purinergic neuromuscular junction that still holds today (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of synthesis, storage, release, and inactivation of ATP at purinergic nerves as depicted by Burnstock for purinergic neuromuscular junctions in 1972 [3]. Reproduced with permission from the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics

Evidence for extracellular hydrolysis of ATP in tissue perfusates was provided already in the 1930s. But biochemical approaches to a mechanistic analysis were developed later. Since ATP is hydrolyzed intracellularly and by broken tissue, convincing evidence for cell surface-located ATP hydrolysis could initially only be obtained by analysis of dispersed and intact cells. First evidence was provided in 1945 in carefully washed bull spermatozoa by T. Mann in Cambridge [4]. More detailed reports followed this pioneering study [5, 6]. When analyzing nucleated avian erythrocytes, Wladimir A. Engelhardt and Tatjana Wenkstern realized that not only ATP but also ADP or ITP were hydrolyzed [7, 8]. Catalytic activity had an alkaline pH optimum and was blocked by EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid). These two authors introduced the term ecto-ATPase in 1955 [9] as well as the terms ectoenzyme and ecto-apyrase (Engelhardt, 1958, held at the International Symposium on Enzyme Chemistry, Tokyo and Kyoto, 1957, [7] and Wenkstern and Engelhardt in 1959) [8].

Objections and a solution

Yet, the function of this “ectoenzyme” remained obscure. Nucleotides appeared not to be present in appreciable amounts in the extracellular medium. ATPase activity was solely known to relate to cellular energetics and cellular metabolism. Could it have something to do with active transport of substances across the plasma membrane or the control of cell permeability? [7]. This problem persisted for a very long time. Biochemists would not agree that an energy-rich substance such as ATP would at all be released from cells under physiological conditions. And if so, the free enthalpy of hydrolysis had to be employed somehow for an energy-driven cellular process. It would not simply evaporate. This is the merit of Geoff Burnstock: extracellular nucleotide hydrolysis makes sense in the light of purinergic signaling.

Biochemical analysis

In spite of these uncertainties, an increasing number of studies using various cellular systems analyzed the catalytic properties of extracellular nucleotide hydrolysis. The results varied to some extent between individual studies. In retrospect, this is not at all surprising since several “ATPases” exist in the plasma membrane and, even more, several ectoenzymes capable of hydrolyzing extracellular ATP may coexist in the same tissue. But some consensus was achieved that the “enzyme” is a glycosylated membrane integral protein, that the underlying catalytic activity is activated by Ca2+ or Mg2+ in the millimolar range and inhibited by EDTA, and that catalytic activity is highly sensitive to SH reagents but insensitive to inhibitors at concentrations which inhibit mitochondrial ATPase and Na+/K+-ATPase. Km values for ATP were in the low millimolar range. Both purine and pyrimidine nucleotides were hydrolyzed, albeit with differing efficiency. In the 1980s, first attempts were made to purify the ectoenzyme(s). The high detergent sensitivity turned out to be a major obstacle for enzyme purification because the monomeric forms retain little catalytic activity. These early studies were summarized in several reviews [10–20].

Purification and molecular cloning

The rise of molecular genetics made all the difference. Sequence information from purified proteins made it possible to identify the encoding cDNA, followed by heterologous expression and analysis of the protein. Moreover, sequence comparison allowed the identification of paralogues and of orthologues in other species. This was achieved by converging efforts of several laboratories. An ATP diphosphohydrolase was first purified to homogeneity by Christoforidis et al. in 1995 [21] from human placenta. It turned out that the peptide sequences obtained corresponded to a functionally as yet unidentified lymphoid cell activation protein (Cluster of differentiation 39, CD39) that had been cloned and sequenced shortly before [22]. Of note, this was not known to Christoforidis et al. when they submitted their paper. Moreover, a soluble apyrase was cloned from potato tubers in 1996 which was found to be related to CD39 and known apyrases from other organisms. Apparently, there was a group of widely conserved enzymes whose sequences shared typical features such as the “apyrase conserved regions” [23]. In the same year, this laboratory demonstrated ecto-apyrase activity of CD39 by expression in COS-7 cells [24]. Moreover, peptide sequences from a bovine aorta-derived ATP diphosphohydrolase revealed identity with CD39 [25]. Similarly, expression of CD39 in COS-1 cells confirmed its ecto-ADPase activity and highlighted its role as a prime endothelial thromboregulator [26]. The ice was broken. While it was originally thought that there was only a single mammalian “ecto-apyrase,” a paralog was soon sequenced and expressed by Kegel et al., in 1997 [27]. Surprisingly, it turned out to preferentially hydrolyze ATP and appeared to function as an “ecto-ATPase” rather than an “ecto-apyrase” [28]. Moreover, four paralogs were identified in 1998 in the human genome, demonstrating that an entire gene and protein family must exist [29]. We now know that eight paralogs are encoded in the mammalian genome, all hydrolyzing nucleotides only, four of which are typical surface-located ectonucleotidases (NTPDase1, 2, 3, and 8) (Fig. 2). Related enzymes are found in invertebrates, plants, yeast, protozoans, and bacteria [30]. E-NTPDases share common sequence motifs with members of the ASKHA (acetate and sugar kinases/Hsc70/actin) superfamily of phosphotransferases [1, 31, 32] .

Fig. 2.

Membrane topology of NTPDases 1, 2, 3, and 8 and eN (ecto-5′-nucleotidase). The boxes in the NTPDase extracellular loop represent the position of the apyrase conserved regions. eN is GPI-anchored. The GPI anchor may be cleaved by endogenous phospholipases resulting in the release of the enzyme into the interstitial space. NTPDases have the potential to form homo-oligomeric complexes (dimers to tetramers). eN exists and functions as a noncovalent dimer [1]. The hydrolysis cascade is shown for ATP to adenosine. But it applies also to other nucleoside triphosphates (NTP → NDP → NMP; NMP → nucleoside). Purinergic receptors activated by nucleotides and adenosine are indicated below

The years following envisaged impressive progress in further characterizing proteins and genes, using mutation studies, developing inhibitors, resolving atomic structures, and analyzing their function in physiological and pathophysiological conditions. The four surface-located E-NTPDases are glycosylated and share their general membrane topology with two transmembrane domains, which play an important role in function and regulation of the enzymes in addition to anchoring the proteins in the plasma membrane (Fig. 2). The formation of oligomers is essential for full catalytic activity. The biochemical properties of the E-NTPDases, their splice variants, and their tissue distribution have been reviewed in detail [1, 19, 20, 32–36].

Confusing nomenclature

Considerable confusion existed regarding nomenclature. Different names had been assigned by different groups and to individual paralogues. Moreover, the often-used term ecto-ATPase for the ecto-ATP diphosphohydrolase appeared misleading since it disguised the fact that also ADP (an agonist of several P2Y receptors) is hydrolyzed with AMP as the final hydrolysis product. Moreover, not only ATP and ADP but also other nucleoside tri- and diphosphates were hydrolyzed. The author of this article thus put together a nomenclature committee which finally met at the conference on “Ecto-ATPases and related ectonucleotidases” held in Diepenbeek, Belgium, in 1999 where it was agreed to apply a strictly biochemical enzyme nomenclature and to name this new protein family ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase family (E-NTPDase family) (EC: EC 3.6.1.5) and its individual members NTPDase1, NTPDase2, and so on [35, 37]. While the name CD39 is frequently used for NTPDase1 in studies merely relating to its catalytic function, the author holds that the enzyme nomenclature should be applied.

Crystal structures and catalytic cycle

Of central importance for understanding the molecular mechanisms of hydrolysis and the development of inhibitors was the resolution of crystal structures of E-NTPDases. First structures were obtained of the extracellular domain of rat NTPDase2 [38] and a related soluble NTPDase of the pathogenic bacterium Legionella pneumophila (LpNTPDase1), which is secreted into the replication vacuole [39]. The crystal structures revealed a pseudo-symmetrical arrangement of two extended RNase H fold repeats that is also found in other members of the actin structural superfamily. Two structural domains are formed which are characterized by a central mixed β-sheet and a peripheral layer of mainly α-helices. Co-crystals with substrate analogs allowed to identify the catalytic site and to propose a catalytic mechanism involving the individual apyrase conserved regions. The same catalytic site is employed in the hydrolysis of nucleoside di- and triphosphates. During the catalytic cycle, the domains undergo rotational movements supporting the idea that the previously described impact of transmembrane helix dynamics on activity is achieved by coupling to a domain motion (Fig. 3) [40, 41].

Fig. 3.

Ectodomain structure of NTPDase1 and eN. To mark the active site of rat NTPDase1 (chain A of protein data bank [pdb] id 3zx3), the non-hydrolysable ATP analogue AMPPNP (β,γ-imidoadenosine 5′-triphosphate) (red) and a calcium ion (black sphere) have been superimposed from rat NTPDase2 structure (pdb id 3cja). For the homodimeric eN, the domains of one monomer are depicted in blue and green, whereas the other subunit is shown in yellow and orange. The catalytic zinc ions are shown in black and the structural Ca2+ ions in gray. Adenosine (red) is bound to the C-terminal domains of the open state structure of eN (pdb id 4h2i), and AMPCP (adenosine 5′-[α,β-methylene]diphosphate) (red) is bound to the active site in the closed state structure (pdb id 4h2i). The figure was kindly provided by Norbert Sträter, Leipzig, Germany

Development of inhibitors

Multiple studies have highlighted the involvement of ectonucleotidases in pathological conditions. The interplay of ectonucleotidases with the nucleotide and adenosine receptor systems has come increasingly into focus. Alterations in extracellular nucleotide and adenosine levels can increase or decrease P2 receptor and P1 receptor activity. The development of potent and subtype-specific ectonucleotidase inhibitors thus appeared mandatory [42]. This was a field Geoff Burnstock was particularly interested in. In the 1990s, his group published a series of papers on “ecto-ATPases,” which mostly focused on the characterization of enzyme inhibitors [13]. The development of potent and specific inhibitors turned out to be a challenge. Inhibitors should not affect nucleotide receptors or other types of ectonucleotidases—which all share nucleotide-binding sites. And they should not become hydrolyzed. While several E-NTPDase inhibitors have been developed, potent subtype-specific inhibitors are scarce. Most of these are ATP analogs. Other classes concern polyoxometalates, negatively charged metal complexes, anthraquinone derivatives, Schiff bases of tryptamine, quinoline derivatives, and thiadiazolopyrimidones [43–46]. The elucidation of the molecular structure of mammalian E-NTPDases now permits a structure-guided approach of inhibitor development with the ultimate goal of drug design [47].

Therapeutic approaches

Equally important were studies which generated subtype-specific antibodies for analyzing the distribution of the individual enzymes in mammalian tissues [42] and the generation of mice in which individual NTPDases were deleted. The first gene encoding a mammalian NTPDase deleted from the germline was Entpd1 [48]. The study proved its fundamental role in hemostasis and thrombosis. This was followed by the deletion of Entpd2, the gene encoding NTPDase2, which allowed to analyze the function of the enzyme in taste buds [49], followed by the deletion of NTPDas3 [50]. Moreover, transgenic overexpression of NTPDase1 in mice or pigs permitted insight into its role in multiple organ systems. One outcome was the attenuation of myocardial infarction by decreasing infarct size [51–53], confirming previous results emphasizing the important role of ATP hydrolysis and in particular of NTPDase1 in the interplay with nucleotide receptors in the control of vascular function [54, 55]. Moreover, the benefit of administration of soluble apyrase or of induction of NTPDase1 by adenoviral vectors on several models of organ transplantation has been investigated [56]. By now, multiple organ systems and disease models including cancer, immunosuppression, and inflammation have been studied. Recently, the clinical evaluation of anti-NTPDase1 monoclonal antibodies for cancer therapy has been initiated [57]. Only a selection of overviews can be cited here [58–70].

Ecto-5′-nucleotidase

Biochemical properties

This enzyme was first described in extracts of heart tissue by J.L. Reis in 1934 who named it “5-nucleotidase” [71]. He realized that “5-nucleotidase” differs from nonspecific phosphatases already known at the time as it showed high specificity towards nucleoside monophosphates (Fig. 2). In contrast to NTPDases, 5′-nucleotidase was intensively investigated early on [72, 73]. In 1974, it was shown that 5′-nucleotidase is an ectoenzyme in several cell types [74–76]. As a result of adenosine production, scavenging of extracellular nucleotides (including nutrition), involvement in vasodilation, neurotransmission, or hemostasis had been described [77]. The glycoprotein eN is a major enzyme producing adenosine from extracellular AMP and thus for activation of adenosine receptors [78]. Before this context had been elucidated, eN was widely used as a membrane marker and for the analysis of plasma membrane recycling [79]. Eukaryotic eN functions as a noncovalent dimeric Zn2+-binding protein, with reported Km values for AMP between 1 and 50 μM. ATP and ADP are competitive inhibitors of mammalian eN with Ki values in the low micromolar range. This is important, since due to feed forward inhibition, adenosine formation from ATP or ADP will be considerably delayed until extracellular nucleotide levels have fallen into the micromolar range [1].

While it was originally assumed that eN is an integral membrane protein, it was shown by several groups that it can be released by phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C and thus must be anchored to the plasma membrane by a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor [80]. Primary structures were first obtained for the enzyme from rat liver [81], human placenta [82], and the brain of the electric ray [83]. Sequence comparison revealed that eN can be grouped into the calcineurin superfamily of dinuclear metallophosphatases with multiple members in prokaryotes, invertebrates, and vertebrates. The molecular and functional properties of eN have been reviewed [1, 84, 85]. Interestingly, humans express several transcript variants [86].

Nomenclature

As for NTPDases, the nomenclature of 5′-nucleotidases was initially confusing. Apparently, there existed also soluble forms. Whereas some shared properties with eN, others clearly differed regarding catalytic properties. Therefore, an attempt was made by the author of this article to classify the various types of 5′-nucleotidases, and a new nomenclature was suggested [80]. One of the soluble forms was assigned to eN, generated by cleavage of the GPI anchor. At that time, no sequence information was available for soluble 5′-nucleotidases. After the sequences of the six intracellular and soluble 5′-nucleotidases had been revealed, the nomenclature was adapted accordingly [87]. CD73 (cluster of differentiation 73) is frequently used as an alternative name in studies addressing eN.

Crystal structures and inhibitors

Crystal structures were first obtained for Escherichia coli 5′-nucleotidase which served as a model for mammalian eN [88, 89]. In 2012, crystal structures of both the open and closed form of human eN lacking the membrane anchor were determined [90, 91]. These studies revealed an extensive active site closure movement involving the N- and C-terminal domains of the eN monomer, which is thought to be necessary for human eN catalysis, permitting substrate binding and product release (Fig. 3). In addition, the active site closure movement may control eN substrate specificity towards AMP and thereby inhibition by ADP and ATP. It is now possible to design structure-based potent and selective small molecule inhibitors for future drug development. This is important as the hydrolysis product adenosine is involved in numerous pathologies. Progress had been made with several naturally occurring phenolic compounds and flavonoids or anthraquinone dye derivatives [44, 92]. A catalytically active soluble rat eN purified after heterologous expression in insect cells [93] has been widely used for drug screening. Recently, small molecule inhibitors with subnanomolar Ki values at human and rat eN could be developed, which are derivatives of purine and pyrimidine nucleotides. Moreover, high-resolution co-crystal structures revealed insight into the binding mode and represent an excellent basis for drug development [57, 94–96]. Similarly, monoclonal antibodies are applied as inhibitors of eN and may be employed as therapeutic agents [97–99].

Highly relevant for adenosine signaling

Ecto-5′-nucleotidase plays an important role in tissue homeostasis and pathology in many organ systems and in acute and chronic inflammation [2]. This is particularly relevant in the context of acute and chronic types of injury, where eN is essential for maintaining tissue integrity and recovery [69, 86]. Important insight was obtained by targeted disruption of the Nt5e gene in mice revealing that vascular leakage was significantly increased in multiple organs and identifying the enzyme as a critical mediator of vascular leakage in vivo [100]. Moreover, genetic deletion of eN in mice is associated with a proinflammatory phenotype suggesting that eN-mediated adenosine formation represents a key innate mechanism to attenuate tissue inflammation [101, 102]. Behavioral analyses of eN knockout mice suggest that eN is involved in the regulation of learning and memory and psychomotor coordination [103]. Numerous studies analyzing Nt5e-depleted mice followed [85]. More recently, eN has gained considerable attention as a target for cancer treatment. Both ATP and adenosine accumulate at high levels in inflammatory and tumor sites. They play a central role in immune cell regulation and tumor cell proliferation. eN is upregulated in various types of cancer. The immunosuppressive adenosine impairs antitumor responses and enhances tumor growth and metastasis. Targeted eN (as well as NTPDase1) therapy using inhibitors is therefore an important approach to effectively control tumor growth [57, 99, 104–106].

Résumé

Fifty years after establishing the concept of purinergic signaling by Geoff Burnstock and after about 80 years following the discovery of the two types of ectonucleotidases and numerous studies which elucidated their functional and structural properties, the time is now ripe for harvest. This concerns in particular the application of new tools for identifying the pathophysiological involvement of the enzymes in purinergic signaling in the various organ systems and the development of tailored therapies for human diseases.

Herbert Zimmermann

received his PhD in natural sciences from the University of Regensburg, Germany in 1971. Currently he is working as professor emeritus at the Department of Cell Biology and Neuroscience, Faculty of Biosciences at the Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany. His research interests include the molecular and cellular biology of components of the purinergic signaling pathway (ectoenzymes, receptors), adult neurogenesis, synaptic vesicle proteins, synaptic vesicle turnover.

Authors’ contributions

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on A Tribute to Professor Geoff Burnstock.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Sträter N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:437–502. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yegutkin GG. Enzymes involved in metabolism of extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides: functional implications and measurement of activities. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;49:473–497. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2014.953627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnstock G. Purinergic nerves. Pharmacol Rev. 1972;24:509–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mann T. Studies on the metabolism of semen: 1. General aspects. Occurrence and distribution of cytochrome, certain enzymes and coenzymes. Biochem J. 1945;39:451–458. doi: 10.1042/bj0390451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmermann H, Mishra SK, Shukla V, Langer D, Gampe K, et al. Ecto-nucleotidases, molecular properties and functional impact. An. de la Real Acad Nac de Farm. 2007;73:537–566. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann H. ATP and acetylcholine, equal brethren. Neurochem Int. 2008;52:634–648. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engelhardt WA. Enzymes as structural elements of physiological mechanisms. I.U.B. Symp Ser. 1958;2:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenkstern TW, Engelhardt WA. The adenosine polyphosphatase localized on the surface of nucleated red corpuscles. Folia Haematol Int Mag Klin Morphol Blutforsch. 1959;76:422–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venkstern TV, Engelgardt VA. Poverkhnostno-lokalizovannaia adenozinpolifosfataza iadernykh eritrotsitov (adenosine-polyphosphatase of surfaces of nuclear erythrocytes) Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1955;102:133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee RK. Ecto-ATPase. Mol Cell Biochem. 1981;37:91–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02354932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pearson JD. Ectonucleotidases: measurement of activities and use of inhibitors. Methods Pharmacol. 1985;6:83–107. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhalla NS, Zhao D. Cell membrane Ca2+/Mg2+ ATPase. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1988;52:1–37. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(88)90006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziganshin AU, Hoyle CHV, Burnstock G. Ecto-enzymes and metabolism of extracellular ATP. Drug Dev Res. 1994;32:134–146. doi: 10.1002/ddr.430320303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plesner L. Ecto-ATPases: identities and functions. Int Rev Cytol. 1995;158:141–214. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarkis JJF, Battastini AMO, Oliveira EM, et al. ATP diphosphohydrolases: an overview. Ciência Cultura. 1995;47:131–136. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaudoin AR, Sévigny J, Picher M. ATP-diphosphohydrolases, apyrases, and nucleotide phosphohydrolases: biochemical properties and functions. Biomembranes. 1996;5:369–401. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmermann H. Biochemistry, localization and functional roles of ecto-nucleotidases in the nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;49:589–618. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(96)00026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zimmermann H. Extracellular purine metabolism. Drug Dev Res. 1996;39:337–352. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2299(199611/12)39:3/4<337:AID-DDR15>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmermann H. Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362:299–309. doi: 10.1007/s002100000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimmermann H, Braun N. Ecto-nucleotidases—molecular structures, catalytic properties, and functional roles in the nervous system. Prog Brain Res. 1999;120:371–385. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christoforidis S, Papamarcaki T, Galaris D, Kellner R, Tsolas O. Purification and properties of human placental ATP diphosphohydrolase. Eur J Biochem. 1995;234:66–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.066_c.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maliszewski CR, Delespesse GJ, Schoenborn MA, Armitage RJ, Fanslow WC, Nakajima T, Baker E, Sutherland GR, Poindexter K, Birks C. The CD39 lymphoid cell activation antigen. Molecular cloning and structural characterization. J Immunol. 1994;153:3574–3583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handa M, Guidotti G. Purification and cloning of a soluble ATP-diphosphohydrolase (apyrase) from potato tubers (Solanum tuberosum) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:916–923. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang TF, Guidotti G. CD39 is an ecto-(Ca2+,Mg2+)-apyrase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9898–9901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.17.9898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaczmarek E, Koziak K, Sévigny J, Siegel JB, Anrather J, Beaudoin AR, Bach FH, Robson SC. Identification and characterization of CD39/vascular ATP diphosphohydrolase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33116–33122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.33116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcus AJ, Broekman MJ, Drosopoulos JH, Islam N, Alyonycheva TN, Safier LB, Hajjar KA, Posnett DN, Schoenborn MA, Schooley KA, Gayle RB, Maliszewski CR. The endothelial cell ecto-ADPase responsible for inhibition of platelet function is CD39. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1351–1360. doi: 10.1172/JCI119294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kegel B, Braun N, Heine P, et al. An ecto-ATPase and an ecto-ATP diphosphohydrolase are expressed in rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:1189–1200. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heine P, Braun N, Heilbronn A, Zimmermann H. Functional characterization of rat ecto-ATPase and ecto-ATP diphosphohydrolase after heterologous expression in CHO cells. Eur J Biochem. 1999;262:102–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chadwick BP, Frischauf AM. The CD39-like gene family: identification of three new human members (CD39L2, CD39L3, and CD39L4), their murine homologues, and a member of the gene family from Drosophila melanogaster. Genomics. 1998;50:357–367. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang T-F, Handa M, Guidotti G. Structure and function of ectoapyrase (CD39) Drug Dev Res. 1998;45:245–252. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2299(199811/12)45:3/4<245:AID-DDR22>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith TM, Kirley TL. Site-directed mutagenesis of a human brain ecto-apyrase: evidence that the E-type ATPases are related to the actin/heat shock 70/sugar kinase superfamily. Biochemistry. 1999;38:321–328. doi: 10.1021/bi9820457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knowles AF. The GDA1_CD39 superfamily: NTPDases with diverse functions. Purinergic Signal. 2011;7:21–45. doi: 10.1007/s11302-010-9214-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirley TL, Crawford PA, Smith TM. The structure of the nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (NTPDases) as revealed by mutagenic and computational modeling analyses. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:379–389. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5301-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robson SC, Sévigny J, Zimmermann H. The E-NTPDase family of ectonucleotidases: structure function relationships and pathophysiological significance. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:409–430. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimmermann H. Ectonucleotidases: some recent developments and a note on nomenclature. Drug Dev Res. 2001;52:44–56. doi: 10.1002/ddr.1097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmermann H. Ectonucleotidases. In: Abbracchio MP, Williams M, editors. Purinergic and pyrimidergic signalling I. Berlin, Heidleberg, New York: Springer-Verlag; 2001. pp. 209–250. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmermann H, Beaudoin AR, Bollen M, et al. Proposed nomenclature for two novel nucleotide hydrolyzing enzyme families expressed on the cell surface. In: Vanduffel L, Lemmens R, et al., editors. Ecto-ATPases and related ectonucleotidases. Maastricht, The Netherlands: Shaker Publishing B.V; 2000. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zebisch M, Sträter N. Structural insight into signal conversion and inactivation by NTPDase2 in purinergic signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6882–6887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802535105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vivian JP, Riedmaier P, Ge H, le Nours J, Sansom FM, Wilce MCJ, Byres E, Dias M, Schmidberger JW, Cowan PJ, d'Apice AJF, Hartland EL, Rossjohn J, Beddoe T. Crystal structure of a Legionella pneumophila ecto-triphosphate diphosphohydrolase, a structural and functional homolog of the eukaryotic NTPDases. Structure. 2010;18:228–238. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zebisch M, Krauss M, Schäfer P, Sträter N. Crystallographic evidence for a domain motion in rat nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (NTPDase) 1. J Mol Biol. 2012;415:288–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zebisch M, Krauss M, Schäfer P, Lauble P, Sträter N. Crystallographic snapshots along the reaction pathway of nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases. Structure. 2013;21:1460–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kukulski F, Lévesque SA, Sévigny J. Impact of ectoenzymes on P2 and P1 receptor signaling. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;61:263–299. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Rashida M, Iqbal J. Therapeutic potentials of ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase, ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase, ecto-5′-nucleotidase, and alkaline phosphatase inhibitors. Med Res Rev. 2014;34:703–743. doi: 10.1002/med.21302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baqi Y. Ecto-nucleotidase inhibitors: recent developments in drug discovery. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2015;15:21–33. doi: 10.2174/1389557515666150219115141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee S-Y, Fiene A, Li W, Hanck T, Brylev KA, Fedorov VE, Lecka J, Haider A, Pietzsch HJ, Zimmermann H, Sévigny J, Kortz U, Stephan H, Müller CE. Polyoxometalates—potent and selective ecto-nucleotidase inhibitors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;93:171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afzal S, Zaib S, Jafari B, Langer P, Lecka J, Sévigny J, Iqbal J. Highly potent and selective ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (ENTPDase1, 2, 3 and 8) inhibitors having 2-substituted-7-trifluoromethyl-thiadiazolopyrimidones scaffold. Med Chem. 2019;16:689–702. doi: 10.2174/1573406415666190614095821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zebisch M, Baqi Y, Schäfer P, Müller CE, Sträter N. Crystal structure of NTPDase2 in complex with the sulfoanthraquinone inhibitor PSB-071. J Struct Biol. 2014;185:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Enjyoji K, Sévigny J, Lin Y, Frenette PS, Christie PD, Esch JSA, II, Imai M, Edelberg JM, Rayburn H, Lech M, Beeler DL, Csizmadia E, Wagner DD, Robson SC, Rosenberg RD. Targeted disruption of cd39/ATP diphosphohydrolase results in disordered hemostasis and thromboregulation. Nat Med. 1999;5:1010–1017. doi: 10.1038/12447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vandenbeuch A, Anderson CB, Parnes J, Enjyoji K, Robson SC, Finger TE, Kinnamon SC. Role of the ectonucleotidase NTPDase2 in taste bud function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:14789–14794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309468110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCoy E, Street S, Taylor-Blake B, et al. Deletion of ENTPD3 does not impair nucleotide hydrolysis in primary somatosensory neurons or spinal cord. F1000Res. 2014;3:163. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.4563.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dwyer KM, Robson SC, Nandurkar HH, Campbell DJ, Gock H, Murray-Segal LJ, Fisicaro N, Mysore TB, Kaczmarek E, Cowan PJ, d’Apice AJF. Thromboregulatory manifestations in human CD39 transgenic mice and the implications for thrombotic disease and transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1440–1446. doi: 10.1172/JCI19560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cai M, Huttinger ZM, He H, Zhang W, Li F, Goodman LA, Wheeler DG, Druhan LJ, Zweier JL, Dwyer KM, He G, d'Apice AJF, Robson SC, Cowan PJ, Gumina RJ. Transgenic over expression of ectonucleotide triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 protects against murine myocardial ischemic injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:927–935. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wheeler DG, Joseph ME, Mahamud SD, Aurand WL, Mohler PJ, Pompili VJ, Dwyer KM, Nottle MB, Harrison SJ, d'Apice AJF, Robson SC, Cowan PJ, Gumina RJ. Transgenic swine: expression of human CD39 protects against myocardial injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:958–961. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marcus AJ, Broekman MJ, Drosopoulos JHF, Olson KE, Islam N, Pinsky DJ, Levi R. Role of CD39 (NTPDase-1) in thromboregulation, cerebroprotection, and cardioprotection. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2005;31:234–246. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-869528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gorman MW, Rooke GA, Savage MV, Jayasekara MPS, Jacobson KA, Feigl EO. Adenine nucleotide control of coronary blood flow during exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1981–H1989. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00611.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robson SC, Wu Y, Sun X, Knosalla C, Dwyer K, Enjyoji K. Ectonucleotidases of CD39 family modulate vascular inflammation and thrombosis in transplantation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2005;31:217–233. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-869527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeffrey JL, Lawson KV, Powers JP (2020) Targeting metabolism of extracellular nucleotides via inhibition of ecto-nucleotidases CD73 and CD39. J Med Chem. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01044 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Dwyer KM, Deaglio S, Gao W, Friedman D, Strom TB, Robson SC. CD39 and control of cellular immune responses. Purinergic Signal. 2007;3:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9050-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schetinger MRC, Morsch VM, Bonan CD, Wyse ATS. NTPDase and 5′-nucleotidase activities in physiological and disease conditions: new perspectives for human health. Biofactors. 2007;31:77–98. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520310205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deaglio S, Robson SC. Ectonucleotidases as regulators of purinergic signaling in thrombosis, inflammation, and immunity. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;61:301–332. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00010-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zimmermann H. Purinergic signaling in neural development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ghiringhelli F, Bruchard M, Chalmin F, Rébé C. Production of adenosine by ectonucleotidases: a key factor in tumor immunoescape. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:473712–473719. doi: 10.1155/2012/473712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chernogorova P, Zeiser R. Ectonucleotidases in solid organ and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:208204–208217. doi: 10.1155/2012/208204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vaughn BP, Robson SC, Longhi MS. Purinergic signaling in liver disease. Dig Dis. 2014;32:516–524. doi: 10.1159/000360498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Takenaka MC, Robson S, Quintana FJ. Regulation of the T cell response by CD39. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:427–439. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Longhi MS, Moss A, Jiang ZG, Robson SC. Purinergic signaling during intestinal inflammation. J Mol Med. 2017;95:915–925. doi: 10.1007/s00109-017-1545-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kishore BK, Robson SC, Dwyer KM. CD39-adenosinergic axis in renal pathophysiology and therapeutics. Purinergic Signal. 2018;14:109–120. doi: 10.1007/s11302-017-9596-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vuerich M, Robson SC, Longhi MS. Ectonucleotidases in intestinal and hepatic inflammation. Front Immunol. 2019;10:507. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dwyer KM, Kishore BK, Robson SC. Conversion of extracellular ATP into adenosine: a master switch in renal health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:509–524. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0304-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang S, Gao S, Zhou D, Qian X, Luan J, Lv X (2020) The role of the CD39-CD73-adenosine pathway in liver disease. J Cell Physiol. 10.1002/jcp.29932 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Reis JL. La nucléotidase et sa relation avec la désamination des nucleotides dans la coeur et dans le muscle. Bull Soc Chim Biol. 1934;16:385–399. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bodansky O, Schwartz MK. 5’-Nucleotidase. Adv Clin Chem. 1968;11:277–328. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2423(08)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sunderman FW. The clinical biochemistry of 5′-nucleotidase. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1990;20:123–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.DePierre JW, Karnovsky ML. Ecto-enzymes of the Guinea pig polymorphonuclear leukocyte. I. Evidence for an ecto-adenosine monophosphatase, adenosine triphosphatase, and -p-nitrophenyl phosphates. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:7111–7120. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)42081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DePierre JW, Karnovsky ML. Ecto-enzyme of granulocytes: 5′-nucleotidase. Science. 1974;183:1096–1098. doi: 10.1126/science.183.4129.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trams EG, Lauter CJ. On the sidedness of plasma membrane enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;345:180–197. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90257-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stanley KK, Newby AC, Luzio JP. What do ectoenzymes do? Trends Biochem Sci. 1982;7:145–147. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(82)90207-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen J-F, Eltzschig HK, Fredholm BB. Adenosine receptors as drug targets—what are the challenges? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:265–286. doi: 10.1038/nrd3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Widnell CC, Kitson RP, Wilcox DK. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase as a probe for the analysis of membrane flow during fluid phase pinocytosis. In: Kreutzberg GW, Reddington M, Zimmermann H, editors. Cellular biology of ectoenzymes. Berlin, Heidelberg, NewYork: Springer-Verlag; 1986. pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zimmermann H. 5’-Nucleotidase: molecular structure and functional aspects. Biochem J. 1992;285(Pt 2):345–365. doi: 10.1042/bj2850345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Misumi Y, Ogata S, Hirose S, Ikehara Y. Primary structure of rat liver 5′-nucleotidase deduced from the cDNA. Presence of the COOH-terminal hydrophobic domain for possible post-translational modification by glycophospholipid. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:2178–2183. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)39958-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Misumi Y, Ogata S, Ohkubo K, et al. Primary structure of human placental 5′-nucleotidase and identification of the glycolipid anchor in the mature form. Eur J Biochem. 1990;191:563–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Volknandt W, Vogel M, Pevsner J, et al. 5′-nucleotidase from the electric ray electric lobe. Primary structure and relation to mammalian and procaryotic enzymes. Eur J Biochem. 1991;202:855–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Resta R, Yamashita Y, Thompson LF. Ecto-enzyme and signaling functions of lymphocyte CD73. Immunol Rev. 1998;161:95–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Colgan SP, Eltzschig HK, Eckle T, Thompson LF. Physiological roles for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:351–360. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5302-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Minor M, Alcedo KP, Battaglia RA, et al. Cell type- and tissue-specific functions of ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2019;317:C1079–C1092. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00285.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bianchi V, Spychala J. Mammalian 5′-nucleotidases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46195–46198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R300032200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Knöfel T, Sträter N. E. coli 5′-nucleotidase undergoes a hinge-bending domain rotation resembling a ball-and-socket motion. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:255–266. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sträter N. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase: structure function relationships. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:343–350. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9000-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Heuts DPHM, Weissenborn MJ, Olkhov RV, Shaw AM, Gummadova J, Levy C, Scrutton NS. Crystal structure of a soluble form of human CD73 with ecto-5′-nucleotidase activity. Chembiochem. 2012;13:2384–2391. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Knapp K, Zebisch M, Pippel J, el-Tayeb A, Müller CE, Sträter N. Crystal structure of the human ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73): insights into the regulation of purinergic signaling. Structure. 2012;20:2161–2173. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Corbelini PF, Figueiró F, das Neves GM, et al. Insights into ecto-5′-nucleotidase as a new target for cancer therapy: a medicinal chemistry study. Curr Med Chem. 2015;22:1776–1792. doi: 10.2174/0929867322666150408112615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Servos J, Reiländer H, Zimmermann H. Catalytically active soluble ecto-5′-nucleotidase purified after heterologous expression as a tool for drug screening. Drug Dev Res. 1998;45:269–276. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2299(199811/12)45:3/4<269:AID-DDR25>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Junker A, Renn C, Dobelmann C, Namasivayam V, Jain S, Losenkova K, Irjala H, Duca S, Balasubramanian R, Chakraborty S, Börgel F, Zimmermann H, Yegutkin GG, Müller CE, Jacobson KA. Structure-activity relationship of purine and pyrimidine nucleotides as ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2019;62:3677–3695. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bhattarai S, Pippel J, Meyer A, Freundlieb M, Schmies C, Abdelrahman A, Fiene A, Lee SY, Zimmermann H, el-Tayeb A, Yegutkin GG, Sträter N, Müller CE. X-ray co-crystal structure guides the way to subnanomolar competitive ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) inhibitors for cancer immunotherapy. Adv Therap. 2019;2:1900075. doi: 10.1002/adtp.201900075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bhattarai S, Pippel J, Scaletti E, Idris R, Freundlieb M, Rolshoven G, Renn C, Lee SY, Abdelrahman A, Zimmermann H, el-Tayeb A, Müller CE, Sträter N. 2-Substituted α,β-methylene-ADP derivatives: Potent competitive ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) inhibitors with variable binding modes. J Med Chem. 2020;63:2941–2957. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Geoghegan JC, Diedrich G, Lu X, Rosenthal K, Sachsenmeier KF, Wu H, Dall'Acqua WF, Damschroder MM. Inhibition of CD73 AMP hydrolysis by a therapeutic antibody with a dual, non-competitive mechanism of action. MAbs. 2016;8:454–467. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2016.1143182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hay CM, Sult E, Huang Q, Mulgrew K, Fuhrmann SR, McGlinchey KA, Hammond SA, Rothstein R, Rios-Doria J, Poon E, Holoweckyj N, Durham NM, Leow CC, Diedrich G, Damschroder M, Herbst R, Hollingsworth RE, Sachsenmeier KF. Targeting CD73 in the tumor microenvironment with MEDI9447. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1208875. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1208875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Perrot I, Michaud H-A, Giraudon-Paoli M, et al. Blocking antibodies targeting the CD39/CD73 immunosuppressive pathway unleash immune responses in combination cancer therapies. Cell Rep. 2019;27:2411–2425.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Thompson LF, Eltzschig HK, Ibla JC, van de Wiele CJ, Resta R, Morote-Garcia JC, Colgan SP. Crucial role for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) in vascular leakage during hypoxia. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1395–1405. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Romio M, Reinbeck B, Bongardt S, et al. Extracellular purine metabolism and signaling of CD73-derived adenosine in murine Treg and Teff cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C530–C539. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00385.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Koszalka P, Ozüyaman B, Huo Y, et al. Targeted disruption of CD73/ecto-5′-nucleotidase alters thromboregulation and augments vascular inflammatory response. Circ Res. 2004;95:814–821. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000144796.82787.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zlomuzica A, Burghoff S, Schrader J, Dere E. Superior working memory and behavioural habituation but diminished psychomotor coordination in mice lacking the ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) gene. Purinergic Signal. 2013;9:175–182. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9344-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Allard B, Longhi MS, Robson SC, Stagg J. The ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73: novel checkpoint inhibitor targets. Immunol Rev. 2017;276:121–144. doi: 10.1111/imr.12528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Di Virgilio F, Sarti AC, Falzoni S, et al. Extracellular ATP and P2 purinergic signalling in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:601–618. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen S, Wainwright DA, Wu JD, Wan Y, Matei DE, Zhang Y, Zhang B. CD73: an emerging checkpoint for cancer immunotherapy. Immunotherapy. 2019;11:983–997. doi: 10.2217/imt-2018-0200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.