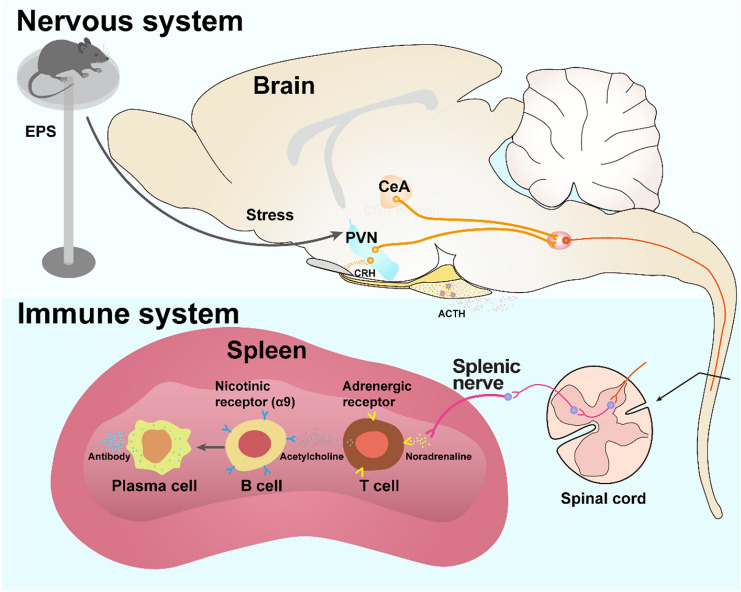

A happy mood helps to build a flourishing immune system. Interactions between the nervous and immune systems have attracted the interest of researchers for decades. It is well known that external stressors can activate the hypothalamus to regulate immune responses via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal cortex (HPA) axis [1]. As well, inflammatory stimuli can activate a rapid anti-inflammatory reflex via the cholinergic vagus nerve pathway. An important target for the nervous system-elicited immune regulation is the spleen, a key organ where immune cells meet pathogens and antigens to trigger innate and adaptive immune responses. Notably, the spleen is mainly innervated by sympathetic nerves [2]. Genetic or surgical ablation of the splenic nerve attenuates endotoxin-triggered innate immune responses and prevents the inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α provoked by vagus nerve stimulation under septic conditions [2–4], demonstrating the pivotal importance of the splenic nerve in anti-inflammatory innate immunity. However, whether a direct neural pathway from the brain to the spleen regulates adaptive immunity remains unknown. Writing in Nature, Zhang and colleagues uncovered that appropriate stress-activated corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) neurons in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and/or central nucleus of the amygdala (PVN/CeA) drive a neural pathway to the spleen to regulate humoral immune defense (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The brain-spleen axis controls humoral immune responses. Appropriate stresses such as shown in the elevated-platform standing (EPS) paradigm activate CRH neurons in the PVN and CeA. These neurons further connect to the spleen via the splenic nerve. When activated, the splenic nerve releases norepinephrine, which binds to the adrenergic receptors on T cells. Activated T cells relay the signals to B cells by secreting acetylcholine that binds to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on B cells. Activation of Chrna9 receptors in B cells promotes the splenic plasma cells formation and antibody production after antigen stimulation.

To determine whether the splenic nerve is directly engaged in adaptive immune responses, Zhang et al. [5] surgically removed the nerve and reported that the antigen-induced formation of T cell-dependent splenic plasma cells (SPPCs) is reduced. By contrast, the formation of T cell-independent SPPCs is not affected upon splenic denervation, suggesting that the splenic nerve is necessary for antigen-triggered T cell-dependent adaptive immunity. Zhang et al. [5] further reported that direct exposure of B cells to acetylcholine (ACh) rather than norepinephrine affects SPPCs formation. Splenic nerves only release norepinephrine [2]. How is the noradrenergic signal shifted to a cholinergic signal in the spleen? A previous study revealed that a subset of CD4+ and choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-expressing T cells abutting the noradrenergic nerve endings in the spleen is able to produce ACh upon nerve stimulation. By releasing ACh, they relay the neural noradrenergic signal to ACh-responsive macrophages to regulate innate immunity [6]. To investigate whether ChAT-expressing T cells are also required for SPCCs formation in adaptive immunity, Zhang et al. ablated ChAT-expressing T cells and found that the number of plasma cells is significantly reduced after antigen immunization [5], suggesting that SPPCs formation relies on ACh derived from ChAT-expressing T cells.

To determine which type of ACh receptor is involved, Zhang et al. [5] examined the expression of ACh receptors in splenic B cells. They found that Chrna9, encoding the α9 nicotinic ACh receptor subunit, is strongly expressed in B cells and deletion of Chrna9 substantially reduces the binding capacity of splenic B cells to ACh. Transplantation of mixed hematopoietic stem cells from Chrna9-KO and B cell-deficient mice into radiation-treated wild-type mice reduces the number of SPPCs after antigen injections. However, this reduction is abolished in mice after splenic denervation, indicating that splenic nerve activation promotes SPPCs differentiation through ACh-mediated α9 nicotinic receptor signaling.

To further dissect the upstream neural pathway controlling splenic nerve activity, Zhang et al. [5] injected pseudo-rabies virus, a trans-synaptic retrograde tracer, into the spleen to trace the upstream inputs. Interestingly, the stress centers, including the PVN and CeA, were densely labelled. These areas are known to harbor predominantly CRH neurons involved in regulating the HPA axis and stress or fear-related responses. Using optogenetic tools and electrophysiological recordings, Zhang et al. showed that optical activation of CRH neurons in the PVN and CeA increases the firing in splenic nerves [5], indicating direct functional connections between CRH neurons and splenic nerves. Further, pharmacogenetic inhibition or genetic ablation of CRH neurons in the PVN and CeA suppresses SPPCs formation after antigen stimulation. Conversely, pharmacogenetic activation of the CRH neurons boosts the number of SPPCs, while splenic denervation abolishes this effect [5], verifying that the connections between PVN/CeA CRH neurons and the splenic nerves are indispensable for SPPCs differentiation.

If activation of the PVN/CeA CRH neuron-splenic nerve pathway boosts adaptive immunity, one would expect that stress-activated PVN/CeA CRH neurons have similar effects. However, previous studies have demonstrated that PVN CRH neurons play an immunosuppressive rather than immunostimulatory role by driving HPA axis activation and glucocorticoid release [7]. Zhang et al. [5] speculated that stress severity might be correlated with glucocorticoid production. To circumvent the potential immunosuppressive impact of glucocorticoid release after severe stress, Zhang et al. developed a model of mild stress, namely elevated-platform standing (EPS) [5]. The acrophobic stress provokes moderate activity of CRH neurons in both the PVN and CeA and enhances SPPCs formation and antibody production. Importantly, EPS-triggered immunostimulatory effects are absent in mice with splenic denervation, suggesting that mild stress boosts humoral immunity through the PVN/CeA-splenic nerve axis.

While it is well-established that the brain can regulate immunity through the HPA axis, Zhang et al. present the first evidence that the activity of CRH neurons control adaptive immunity in the spleen by direct innervation rather than by blood-borne hormones. This study adds to the growing body of research that has revealed the importance of neural activity in the regulation of adaptive immunity [8]. It provides proof-of-principle on how moderate stress enhances adaptive immunity via the brain-immune organ axis and presents exciting perspectives on how mind-immune interactions affect health. Meanwhile, it raises several intriguing questions. Do CRH neurons in the PVN and CeA cross-talk to regulate humoral immunity? If yes, how is their activity orchestrated to exert distinct or opposite effects in response to different intensities of stress? Do different stresses recruit different subsets of CRH neurons participating in different aspects of immune regulation? CRH neurons in the PVN and CeA may represent distinct subpopulations organizing the endocrine, autonomic, and behavioral responses to stress via either the HPA axis or direct projections to limbic and autonomic regions. As shown in the study [5], different from EPS stimulation, prolonged physical restraint (PPR) increases the circulating corticosterone level but suppresses germinal center formation. Possibilities are that distinct CRH subpopulations may differentially respond to EPS and PPR, with the immunosuppressive effects dominated by blood-borne corticosterone, whereas the immunostimulatory effects rely directly on neural circuits. In addition, are there non-CRH neurons or CRH neurons in other brain areas involved in the immune-regulatory pathway? What are the identities of the relay neurons between the PVN/CeA CRH neurons and splenic nerves and how do they participate in the immune regulation in response to stress? It would be interesting to investigate whether the rostral ventrolateral medulla in the brain stem and intermediolateral column in the spinal cord, regions critical for the sympathetic outflow to the cardiovascular system, might be implicated in regulating splenic activity [9, 10]. Finally, is it possible to design similar behavioral interventions to boost human adaptive immunity? It is important to find a clinically applicable approach to transforming daily life stress into a behavioral therapy that is noninvasive and economic, with no medicine required.

With the advent of newly-developed viral tracing and genetic manipulation tools, studies are revealing fascinating neural circuits that regulate mood, recognition, behavior, and immunity. Future studies will continue to reveal how brain activity regulates the physiological functions of peripheral organs. Dissecting the mechanisms by which environmental stimuli interact with the brain-spleen circuits may open new avenues for the improvement of immunity and global health.

There is still a long way to go.

Acknowledgements

This highlight article was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671057), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (2019FZA7009), and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019TQ282).

References

- 1.Tracey KJ. Reflex control of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:418–428. doi: 10.1038/nri2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding X, Wang H, Qian X, Han X, Yang L, Cao Y, et al. Panicle-shaped sympathetic architecture in the spleen parenchyma modulates antibacterial innate immunity. Cell Rep. 2019;27:3799–3807. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosas-Ballina M, Ochani M, Parrish WR, Ochani K, Harris YT, Huston JM, et al. Splenic nerve is required for cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway control of TNF in endotoxemia. PNAS. 2008;105:11008–11013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803237105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, Amella CA, Susarla MTS, Li JH, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor α7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature. 2003;421:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Lei B, Yuan Y, Zhang L, Hu L, Jin S, et al. Brain control of humoral immune responses amenable to behavioural modulation. Nature. 2020;581:204–208. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, Valdés-Ferrer SI, Levine YA, Reardon C, et al. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science. 2011;334:98–102. doi: 10.1126/science.1209985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coutinho AE, Chapman KE. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;335:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Shaanan TL, Azulay-Debby H, Dubovik T, Starosvetsky E, Korin B, Schiller M, et al. Activation of the reward system boosts innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Med. 2016;22:940–944. doi: 10.1038/nm.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou JJ, Ma HJ, Shao JY, Pan HL, Li DP. Impaired hypothalamic regulation of sympathetic outflow in primary hypertension. Neurosci Bull. 2019;35:124–132. doi: 10.1007/s12264-018-0316-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chapp AD, Gui L, Huber MJ, Liu J, Larson RA, Zhu J, et al. Sympathoexcitation and pressor responses induced by ethanol in the central nucleus of amygdala involves activation of NMDA receptors in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:701–709. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00005.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]