This cohort study evaluates the performance of a suicide attempt risk prediction model implemented in a vendor-supplied electronic health record to predict subsequent suicidal ideation and suicide attempt.

Key Points

Question

How well do electronic health record–based suicide risk models perform in the clinical setting, and is performance generalizable?

Findings

This cohort study of 30-day suicide attempt risk among 77 973 patients showed good performance in nonpsychiatric clinical settings at scale and in real time. Numbers needed to screen were reasonable for an algorithmic screening test that required no additional data collection or face-to-face screening to calculate.

Meaning

Suicide attempt risk models can be implemented with accurate performance at scale, but performance is not equal in all clinical settings, which requires model recalibration and updating prior to deployment in new settings.

Abstract

Importance

Numerous prognostic models of suicide risk have been published, but few have been implemented outside of integrated managed care systems.

Objective

To evaluate performance of a suicide attempt risk prediction model implemented in a vendor-supplied electronic health record to predict subsequent (1) suicidal ideation and (2) suicide attempt.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This observational cohort study evaluated implementation of a suicide attempt prediction model in live clinical systems without alerting. The cohort comprised patients seen for any reason in adult inpatient, emergency department, and ambulatory surgery settings at an academic medical center in the mid-South from June 2019 to April 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary measures assessed external, prospective, and concurrent validity. Manual medical record validation of coded suicide attempts confirmed incident behaviors with intent to die. Subgroup analyses were performed based on demographic characteristics, relevant clinical context/setting, and presence or absence of universal screening. Performance was evaluated using discrimination (number needed to screen, C statistics, positive/negative predictive values) and calibration (Spiegelhalter z statistic). Recalibration was performed with logistic calibration.

Results

The system generated 115 905 predictions for 77 973 patients (42 490 [54%] men, 35 404 [45%] women, 60 586 [78%] White, 12 620 [16%] Black). Numbers needed to screen in highest risk quantiles were 23 and 271 for suicidal ideation and attempt, respectively. Performance was maintained across demographic subgroups. Numbers needed to screen for suicide attempt by sex were 256 for men and 323 for women; and by race: 373, 176, and 407 for White, Black, and non-White/non-Black patients, respectively. Model C statistics were, across the health system: 0.836 (95% CI, 0.836-0.837); adult hospital: 0.77 (95% CI, 0.77-0.772); emergency department: 0.778 (95% CI, 0.777-0.778); psychiatry inpatient settings: 0.634 (95% CI, 0.633-0.636). Predictions were initially miscalibrated (Spiegelhalter z = −3.1; P = .001) with improvement after recalibration (Spiegelhalter z = 1.1; P = .26).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, this real-time predictive model of suicide attempt risk showed reasonable numbers needed to screen in nonpsychiatric specialty settings in a large clinical system. Assuming that research-valid models will translate without performing this type of analysis risks inaccuracy in clinical practice, misclassification of risk, wasted effort, and missed opportunity to correct and prevent such problems. The next step is careful pairing with low-cost, low-harm preventive strategies in a pragmatic trial of effectiveness in preventing future suicidality.

Introduction

Suicide prevention begins with risk identification and prognostication. The standard of care remains face-to-face screening and routine clinical interaction. Yet rates of suicidal ideation, attempts, and deaths continue to rise internationally despite increased monitoring and intervention efforts.1 The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic exacerbated contributing factors for suicide and will continue to do so in the post–COVID-19 era.2,3,4 Numerous prognostic models of suicide risk have been published.5 Few have been implemented into real-world clinical systems outside of integrated managed care settings.5,6,7 In some settings, universal screening might reduce risk of downstream suicidality.8 But in-person screening takes time and attention and can be conducted with variable quality.9 Concealed distress also subverts risk identification in face-to-face screening.10 Furthermore, those at risk might not be identified despite health care encounters as recently as the day they die from suicide.11,12,13

Linking scalable, automated risk prognostication with real-world clinical processes might improve suicide prevention.14 The most prominent example of an operational suicide risk prediction with implemented prevention is REACH VET (Recovery Engagement and Coordination for Health—Veterans Enhanced Treatment) from the Veterans Health Administration.6 Similarly, Army STARRS (Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers) demonstrated algorithmic potential in active duty service members.15,16 A number of groups, including ours, have published modeling studies for civilians both nationally (eg, the Mental Health Research Network)5,17,18,19,20 and internationally.21 A recent brief report7 estimated the increased potential workload of a suicide risk prediction model to generate alerts in an integrated managed care setting, Kaiser Permanente. In Europe, linking mobile health and predictive modeling for suicide prevention has been described,22 as have predictive modeling studies developed for national and single-payer cohorts.21,23

While some risk models rely on face-to-face screening data (eg, the Patient Health Questionnaire–9) to calculate risk,17 generating these important predictors relies on existing or changing clinical workflow—a difficult task. In some hospitals, universal screening occurs in the emergency department alone. A model reliant solely on routine, passively collected clinical data, such as medication and diagnostic data, might scale to any clinical setting regardless of screening practices. Few real-world data exist on successes and pitfalls of translating such models into operational clinical systems in the presence or absence of universal screening.7

Like any prognostic test, such as radiographic imaging and laboratory studies, electronic health record (EHR)–based risk models serve as an additional data point for clinical decision-making. When linked to guideline-informed and evidence-based education along with actionable, user-centered decision support, they might improve provision of suicide prevention. Such systems might prompt care outside of routine health encounters, eg, a prioritized telephone call to a high-risk patient who missed an appointment or guidance on assessing means to a primary care clinician who does not do so regularly. Ideally, these systems would improve quality of care while reducing burden on clinicians to respond appropriately at the right times.

Part of a larger technology-enabled suicide prevention program, our work applied the multiphase framework for action-informed artificial intelligence24 to suicide attempt prognostication. We completed phases 1 and 2 in initial model development20 followed by phase 3, replicative studies.18,25 The fourth phase includes design, usability, and feasibility testing for the operational platform before effectiveness testing and practice improvement in the final phase.

We evaluate prospectively the real-time EHR risk prediction platform here (fourth phase) to answer the question, “How well do EHR-based suicide risk models perform in the clinical setting, and is performance generalizable?” Models that fail to validate at this phase, or those not studied in this fashion prior to implementation, might covertly hinder clinical decision-making. Predictive models might be evaluated similarly to any novel prognostic data point (eg, a laboratory or imaging result).26 This validation should account for clinical context, setting, and the presence of universal screening.8

Methods

We studied an observational, prospective cohort of clinical inpatient, emergency department, and ambulatory surgery encounters at a major academic medical center in the mid-South, Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), from June 2019 to April 2020. Predictions were prompted by the start of routine clinical visits in the EHR. Because model validity was untested outside of research systems,27 model predictions did not trigger EHR alerts or decision support.

The VUMC Institutional Review Board approved 2 protocols with waiver of consent given the infeasibility of consenting these EHR-driven analyses across a health system. Only clinical production-grade systems were used to protect privacy and demonstrate feasibility. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.28

Study Outcomes

In this study, the predictive model trained on suicide attempt risk was used to predict both suicide attempt (primary) and suicidal ideation (secondary) within 30 days of discharge.25 Outcomes were ascertained via reference codes (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM]29; eTable in the Supplement). Because we and others have shown imperfect ascertainment from ICD codes for suicide attempt,20,30 our team (C.G.W., J.H., S.S.) manually reviewed coded suicide attempts and verified suicidal behaviors with intent to die.

Our previously published approach was internally valid at multiple time points (eg, 30 days vs 90 days).20 Thirty-day outcomes were selected as the prediction target with input from behavioral health experts involved in local suicide prevention.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We included all adult patients seen in inpatient, emergency department, and ambulatory surgery settings. Individuals with death dates in the Social Security Death Index were right-censored if deaths occurred within 30 days of discharge. Cause-of-death data were not available across the enterprise, so deaths from suicide were not included as prediction targets.

Implementation

Full modeling details have been published20 and are in the eMethods in the Supplement. Briefly, we trained random forests, a nonparametric ensemble machine learning algorithm, on a heterogeneous, retrospective group of adult cases and controls prior to 2017 stored in a deidentified research repository, the Synthetic Derivative.31 These models were validated with a variant of bootstrapping with optimism adjustment, in which each bootstrap iteration was tested against a true holdout set to lessen overfitting.32 Model performance in training to predict suicide attempt within 30 days showed area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.9 (95% CI, 0.9-0.91) on a deidentified data set of 3250 cases of manually validated suicide attempts and 12 695 adults with no history of suicide attempt.20

Predictors included the following:

Demographic data (age, sex, race)

Diagnostic data grouped to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCC) (eg, schizophrenia-related ICD codes mapped to HCC 57)

Medication data grouped to the Anatomic Therapeutic Classification, level IV (eg, citalopram N06AB04 [level V] maps to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors N06AB [level IV])

Past health care utilization (counts of inpatient, emergency department, and ambulatory surgery visits over the preceding 5 years)

Area Deprivation Indices33 by patient zip code

Real-Time Prediction

At registration for inpatient, emergency department, or ambulatory surgery visits, the modeling pipeline used 5 years of historical data to build a vector of predictors. Preliminary analyses showed the 5-year lookback window to perform similarly to models using all historical data. The predictive model then generated a probability of subsequent suicide attempt in 30 days. Here, we validate that probability to predict encounters for suicide attempt or suicidal ideation in the subsequent 30 days.

Recalibration

Calibration measures how well predicted probabilities reflect real-world outcome (eg, a 1% risk of suicide attempt means 1 of 100 similar individuals from that population should have the outcome). Miscalibrated models hamper clinical decision-making.34

To enrich signal, the research-grade model20 was trained with a sample of the larger population, increasing potential miscalibration. We anticipated miscalibration and corrected it with logistic calibration,35,36 a univariate logistic regression model with uncalibrated predictions trained on outcomes from June to October to recalibrate predictions from November to April.

Evaluation

Performance evaluation included discrimination: AUROC, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), risk concentration; calibration: calibration slope and intercept, Spiegelhalter z statistic (P > .05 indicates the model is well calibrated37); and usefulness: number needed to screen (NNS, the reciprocal of PPV). Evaluation accounted for the presence or absence of universal screening. To generate CIs and analyze sensitivity to temporal length of EHRs, we varied the minimum length of medical records per performance analysis from all medical records (ie, including records for new patients up to medical records at least 2 years in length). Statistical analyses were conducted in Python, version 3.7 (Python Software Foundation), and in R, version 3.6.1 (R Foundation).

Results

The study included 115 905 predictions for 77 973 patients (42 490 [54%] men, 35 404 [45%] women, 60 586 [78%] White, 12 620 [16%] Black) over 296 days, approximately 392 predictions per day (Table 1). Our analysis right-censored 1326 patients for all-cause death within 30 days of the preceding encounter. Because patients might be directly admitted without emergency department care, the subtotals per setting sum to greater than enterprisewide totals.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Care site | Total | Race | Sex | Age, median, y | Utilization | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Black | Asian | Unknown | Other | Male | Female | Unknown | Median encounters per month | Length of stay, d | Medical record length, median, y | ||||

| Median | Mean | |||||||||||||

| Medical center wide | 77 973 | 60 586 | 12 620 | 1454 | 1233 | 2080 | 42 490 | 35 404 | 79 | 52.0 | 10 923 | 0.3 | 1.9 | 9.0 |

| Behavioral health | 2905 | 2278 | 497 | 55 | 53 | 23 | 1532 | 1373 | 0 | 37.0 | 317 | 0.3 | 1.6 | 5.2 |

| Emergency department | 33 235 | 23 650 | 7409 | 646 | 387 | 1143 | 15 862 | 17 305 | 68 | 46.7 | 3551 | 0.3 | 2 | 5.3 |

| Adult hospital | 46 389 | 38 047 | 5848 | 850 | 678 | 966 | 20 540 | 25 841 | 8 | 57.1 | 6390 | 2.3 | 4.5 | 5.2 |

Recorded outcomes numbered 129 suicide attempts across 85 individuals (sex: 39 men [46%], 46 women [54%]; race: 64 White [75%]; 18 Black [21%], 3 non-White/non-Black [4%]; 23 repeat attempters) and 946 encounters for suicidal ideation across 395 individuals (sex: 222 men [56%], 156 women [39%]; race: 287 White [73%], 78 Black [20%], 30 non-White/non-Black [8%]; 170 repeat ideators). Manual medical record review of coded suicide attempts had PPV greater than 0.9 in ICD-10-CM with an interrater agreement κ of 1, notably higher than the PPV of 0.58 for ICD-9 in a medical record validation of 5543 medical records in prior work at VUMC.20

Model Performance

Cohort criteria affect model performance, as we and others have shown.38 Analyses considered duration of EHRs per patient, clinical settings (eg, inpatient vs emergency department), and universal screening. Demographic characteristics of sex (not gender, which lacks reliable identification in most EHRs) and race were also considered. Performance by length of EHR is shown in aggregate for each outcome (Table 2).

Table 2. Prospective Electronic Health Record (EHR) Validation by Length of Individual EHRs, April 2019 to June 2020.

| Care Site | AUROC (95% CI) | Brier (95% CI) | Spiegelhalter z statistic (95% CI) | Spiegelhalter z, P value (95% CI) | Calibration slope (95% CI) | Calibration intercept (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation | ||||||

| Medical center wide | 0.836 (0.836 to 0.837) | 0.009 (0.009 to 0.009) | −1.362 (−1.592 to −1.132) | .29 (.25 to .33) | 0.273 (0.27 to 0.276) | −2.974 (−2.994 to −2.953) |

| Emergency department | 0.777 (0.776 to 0.778) | 0.012 (0.012 to 0.012) | −2.735 (−2.851 to −2.618) | .01 (.01 to .01) | 0.342 (0.334 to 0.351) | −2.605 (−2.643 to −2.568) |

| Adult hospital | 0.77 (0.769 to 0.772) | 0.002 (0.002 to 0.002) | −10.632 (−10.876 to −10.387) | <.001 (<.001 to <.001) | 0.08 (0.079 to 0.08) | −5.432 (−5.452 to −5.412) |

| Behavioral health | 0.634 (0.633 to 0.636) | 0.109 (0.108 to 0.109) | 27.305 (27.066 to 27.544) | <.001 (<.001 to <.001) | 0.075 (0.073 to 0.077) | −1.68 (−1.69 to −1.67) |

| Suicide attempt | ||||||

| Medical center wide | 0.797 (0.796 to 0.798) | 0.001 (0.001 to 0.001) | −24.683 (−24.933 to −24.433) | <.001 (<.001 to <.001) | 0.189 (0.186 to 0.191) | −5.492 (−5.499 to −5.485) |

| Emergency department | 0.7 (0.699 to 0.7) | 0.002 (0.002 to 0.002) | −18.235 (−18.373 to −18.097) | <.001 (<.001 to <.001) | 0.113 (0.112 to 0.113) | −5.788 (−5.793 to −5.784) |

| Adult hospital | 0.842 (0.841 to 0.842) | 0.001 (0.001 to 0.001) | −14.828 (−15.05 to −14.605) | <.001 (<.001 to <.001) | 0.142 (0.141 to 0.142) | −6.462 (−6.48 to −6.444) |

| Behavioral health | 0.544 (0.539 to 0.548) | 0.011 (0.011 to 0.011) | −5.539 (−5.567 to −5.511) | <.001 (<.001 to <.001) | 0.175 (0.167 to 0.183) | −3.882 (−3.914 to −3.85) |

Abbreviation: AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

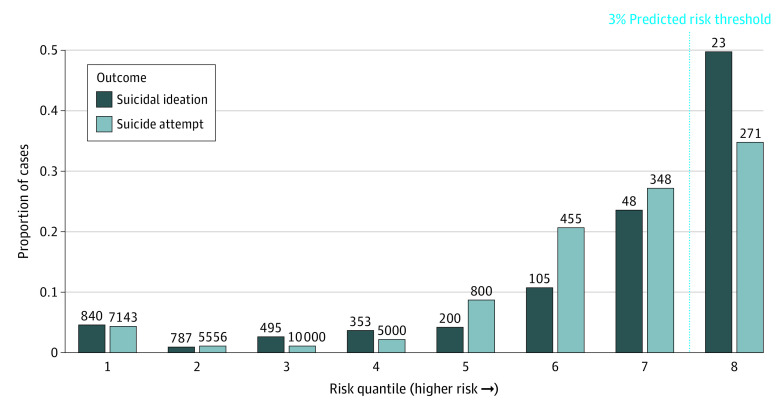

Risk Concentration and NNS

Risk concentration plots for all encounters are shown (Figure 1) with NNS, the reciprocal of PPV, per quantile. The highest risk quantiles have an NNS of 23 and 271 for suicidal ideation and suicide attempt, respectively.

Figure 1. Risk Concentration by Outcome .

Values above each bar indicate the number needed to screen.

Evaluation by Status of Universal Screening

Metrics by predicted risk quantile are shown for suicide attempt risk (Table 3). In settings with universal screening, the lowest risk quantile (n = 6795) with predicted risk threshold near 0 had a PPV of 0.1% for suicidal ideation and approximately 0 for suicide attempt. The highest risk quantile (n = 5457) above a threshold of 3.2% had a PPV of 3% for suicidal ideation and 0.3% for suicide attempt.

Table 3. Predictive Metrics by Risk Bin and Presence or Absence of Screening.

| Risk bin | Prediction ranges | No. in bin | No. of cases | PPV | NNS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Settings without universal screening | |||||

| 1 | 0 | 23 589 | 2 | 8.00E-05 | 12 500 |

| 2 | 0.000006-0.0005 | 2842 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 3 | 0.0005-0.002 | 6894 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 4 | 0.002-0.004 | 6376 | 1 | 0.00016 | 6250 |

| 5 | 0.004-0.006 | 6103 | 1 | 0.00016 | 6250 |

| 6 | 0.006-0.01 | 6582 | 8 | 0.00122 | 820 |

| 7 | 0.01-0.02 | 6495 | 17 | 0.00262 | 382 |

| 8 | 0.02-0.24 | 6517 | 29 | 0.00445 | 225 |

| Universal screening settings | |||||

| 1 | 0 | 6795 | 2 | 0.00029 | 3448 |

| 2 | 0.000008-0.0002 | 2752 | 1 | 0.00036 | 2778 |

| 3 | 0.0002-0.0004 | 3078 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| 4 | 0.0004-0.0007 | 3167 | 4 | 0.00126 | 794 |

| 5 | 0.0007-0.015 | 3153 | 7 | 0.00222 | 450 |

| 6 | 0.015-0.019 | 3166 | 10 | 0.00316 | 316 |

| 7 | 0.019-0.03 | 3171 | 4 | 0.00126 | 794 |

| 8 | 0.03-0.04 | 3115 | 10 | 0.00321 | 312 |

| 9 | 0.04-0.36 | 3155 | 7 | 0.00222 | 450 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NNS, number needed to screen; PPV, positive predictive value.

In settings without universal screening, the highest risk quantile (n = 4220) above a threshold of 3.2% had a PPV of 4.3% for suicidal ideation and 0.4% for suicide attempt. The lowest risk quantile (n = 23 589) of predicted risk near 0 had a PPV of 0.1% for suicidal ideation and 0 for suicide attempt.

Risk Prediction Performance by Demographic Subgroup

The NNS for suicide attempt in the highest risk quantiles for men and women in the medical center–wide cohort were 256 and 323, respectively. By race, as coded in the EHR (White, Black), the NNS was 373 for White patients, 176 for Black patients, and 407 for non-White and non-Black patients.

Calibration

In the first 5 months, predictions were miscalibrated (Spiegelhalter z = −3.1; P = .001). We applied logistic recalibration using those first 5 months, with improved calibration (Spiegelhalter z = 1.1; P = .26) in the subsequent 5-month study period.

Discussion

This study validated performance of a published suicide attempt risk model20 using real-time clinical prediction in the background of a vendor-supplied EHR. Primary findings include accuracy at scale regardless of face-to-face screening in nonpsychiatric settings. We note feasible NNS in the highest predicted risk quantiles with potential for reduced screening workload for those at lowest risk. Overall performance was not sensitive to temporal length of EHRs. The decision of minimum length of EHR to display an alert or prediction for an individual patient, however, will be the subject of future decision support testing.

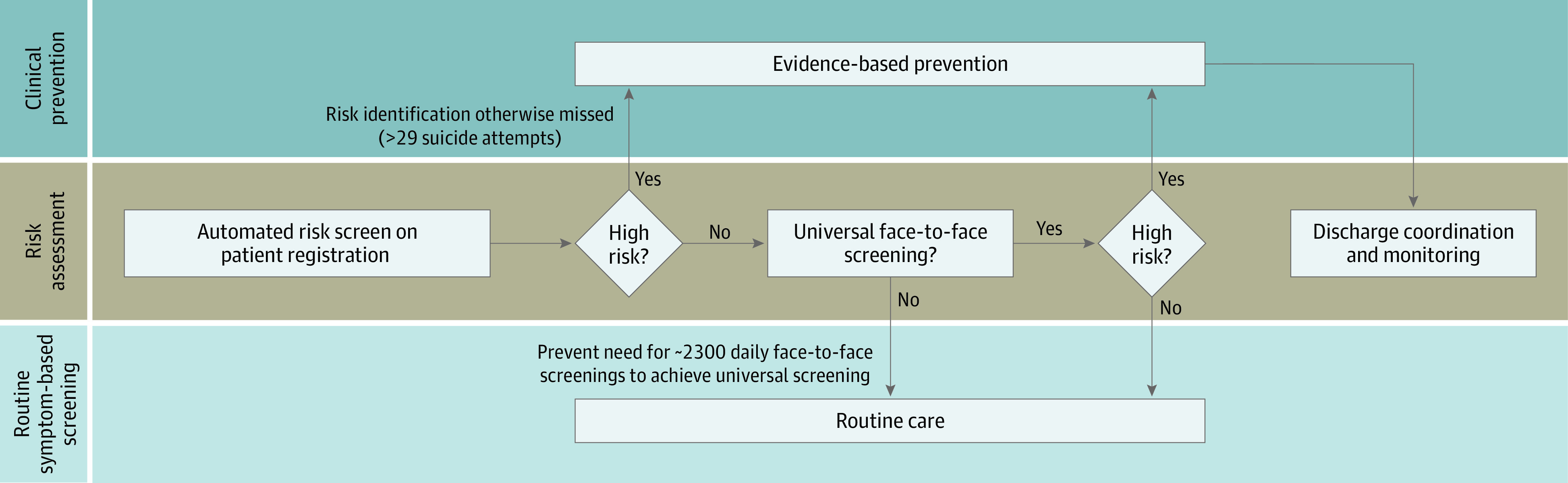

The potential implications of this work influence screening practices, clinical decision-making, and care coordination. Regarding screening, both false negatives and false positives have been considered weaknesses of suicide-focused risk models in systematic review.5 Here, we note very low false-negative rates in the lowest risk tiers both within (0.02%) and without (0.008%) universal screening settings (Table 3). Assuming that face-to-face screening takes, on average, 1 minute to conduct, automated screening for the lowest quantile alone would release 50 hours of clinician time per month. Regarding false positives, the NNS of 271 was feasible in the highest risk group. Suicidal ideation, even more common, had a better NNS of 23. For context, NNS was 418 for screening for dyslipidemia to prevent cardiac death when it was introduced.39 The present study provides further evidence that current models might be best suited to direct prevention to suicidal ideation and attempts—more common yet still in the causal pathway for death from suicide.5 A representative screening protocol is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Artificial Intelligence–Enabled Suicide Screening Protocol.

Regarding clinical decision-making, this study suggests clinical utility in identifying those who might not otherwise be assessed for new symptoms, symptomatic worsening, or life stressors not captured in the EHR. Moreover, linking automated risk stratification with evidence-based education on imminent risk, means assessment, and appropriate clinical triage might prove impactful even in the setting of low PPV.40

Regarding care coordination, risk models of rare outcomes enable longitudinal monitoring for those who might be at longer-term risk of attempts, (eg, 1-2 years, not 30 days).40 Current care coordination in many systems relies on manually curated patient tracking and local workflows by individual clinics or clinicians. Automated risk stratification with decision support might ameliorate challenges such as responding to messages from patients unfamiliar to the nurse or covering clinician, prompting telephone calls to those identified at risk who miss scheduled appointments, and facilitating coordinated care across disparate clinical departments.

A useful model must be well calibrated to reflect reality. Published models often originate from data sets that sample from a larger population to reduce case imbalance given rare outcomes, such as suicide attempts. Once trained, such models risk poor calibration where real-world outcome prevalence does not reflect research. Our risk model is one such example. Calibration of our implemented model was improved with facile logistic recalibration using earlier data to recalibrate later predictions. More sophisticated means of diagnosing and correcting miscalibration and drift merit consideration.41,42,43

One model does not fit all. Model performance was lower in psychiatric compared with nonpsychiatric settings. This model was trained on a heterogeneous mix of medical records prior to 2017. First, prevalent mental health–related risk factors in psychiatric settings might worsen model discrimination compared with the training sample. Second, outcomes were rare in those settings, and cohorts were concomitantly smaller. Third, because psychiatric care is likely to address suicidality, care in those settings confounds pure prognostic accuracy. Such therapeutic differences might be well suited to counterfactual prediction in the future.44 Future work should include development and validation of site-specific predictive models—or models that will be “site aware” in deployment.

Without attention to these differences and analyses conducted here, intervention might be linked to misspecified models. Moreover, it becomes difficult to assess pure model performance once an intervention is prompted by it. Future iterations of these models (1) might be updated based on site-specific cohorts to improve performance and (2) should include the interventions available to prevent suicide within models themselves to prevent model drift even when the care delivered is accomplishing its intended purpose.27

Strengths of this study include a large, real-world vendor-supplied EHR setting. It incorporates prospective validation on natural cohorts of individuals receiving routine care over the study period. The study included visits across the breadth of a major academic medical center, which improves generalizability. These results complete only part of the fourth phase of action-informed artificial intelligence24 to help prevent suicide. We have designed our models with usability and feasibility in mind, but these have not yet been tested. Our modeling requires no additional screening (eg, the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 or Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale), although future versions might incorporate them to improve risk prognostication. Yet, impact will not be achieved without careful attention to the people and clinical processes to leverage these predictions to prevent suicide.

Limitations

Limitations of this work include a single-center study with low outcome prevalence, particularly for suicide attempt. Predictors included in this model were chosen to optimize scalability and potential generalizability. They rely on structured data ubiquitous in EHRs (diagnostic codes, medications, past utilization, demographic characteristics). However, they also limit the model’s ability to predict suicide attempt risk by failing to capture important predictors recorded in unstructured free text notes, for example, or outside the EHR. Implemented risk models were initially trained on a noncomprehensive subsample of the medical center population. Ascertainment is limited to care at a single medical center, so events occurring at external health systems were not captured. However, this bias is conservative for model performance analyses; suicide attempts that occur outside the study site are false negatives, far more likely to affect and worsen apparent performance metrics given the low number of cases than the inverse. Deaths from suicide were not ascertained in this study. Future work to improve ascertainment and continuously evaluate these models in production is paramount.

Multiple opportunities to expand this work remain. Better understanding of misclassification of risk will improve model performance and potential impact. Novel means of ascertaining suicidality both in and out of individual health systems through health information exchange—such as that available in the Veterans Health Administration; in large health systems, such as HCA Healthcare, Tenet Healthcare, or Kaiser Permanente; or in states, such as Connecticut45—might lead to improved model evaluation and improved performance. Through partnerships such as the Tennessee Department of Health–VUMC Experience,46 we are beginning to devise a system that would bridge the current gap preventing ascertainment of death from suicide.

Suicide prevention will not be achieved through a predictive model alone, regardless of its analytic performance. Pragmatic trials to study real-world effectiveness of these predictive models in concert with thoughtful, user-centered clinical decision support remains the path to achieving clinical impact in suicide prevention.

Conclusions

In this study, implementation of validated predictive models of suicide attempt risk showed reasonable performance at scale and feasible NNS for subsequent suicidal ideation or suicide attempt in a large clinical system. Calibration performance of research-derived models was improved with logistic calibration. Scalable, real-time automated prediction of risk of suicidality through multidisciplinary collaboration is an achievable goal for the growing number of predictive models in this domain. It requires careful pairing with low-cost, low-harm preventive strategies in a pragmatic trial to be evaluated for effectiveness in preventing suicidality in the future.

eMethods. Predictive Modeling Details

eReferences.

eTable. Reference Codes From International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Version 10, Clinical Modification

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Suicide in the world: global health estimates. Published September 9, 2019. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/suicide-in-the-world

- 2.Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, et al. ; COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration . Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):468-471. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30171-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawohl W, Nordt C. COVID-19, unemployment, and suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):389-390. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30141-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reger MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019—a perfect storm? JAMA Psychiatry. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belsher BE, Smolenski DJ, Pruitt LD, et al. Prediction models for suicide attempts and deaths: a systematic review and simulation. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(6):642-651. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler RC, Hwang I, Hoffmire CA, et al. Developing a practical suicide risk prediction model for targeting high-risk patients in the Veterans Health Administration. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26(3):e1575. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kline-Simon AH, Sterling S, Young-Wolff K, et al. Estimates of workload associated with suicide risk alerts after implementation of risk-prediction model. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2021189. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller IW, Camargo CA Jr, Arias SA, et al. ; ED-SAFE Investigators . Suicide prevention in an emergency department population: the ED-SAFE study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):563-570. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vannoy SD, Robins LS. Suicide-related discussions with depressed primary care patients in the USA: gender and quality gaps. a mixed methods analysis. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000198. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox DW, Ogrodniczuk JS, Oliffe JL, Kealy D, Rice SM, Kahn JH. Distress concealment and depression symptoms in a national sample of Canadian men: feeling understood and loneliness as sequential mediators. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020;208(6):510-513. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laanani M, Imbaud C, Tuppin P, et al. Contacts with health services during the year prior to suicide death and prevalent conditions: a nationwide study. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:174-182. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):870-877. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmedani BK, Westphal J, Autio K, et al. Variation in patterns of health care before suicide: a population case-control study. Prev Med. 2019;127:105796. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institute of Mental Health . Identifying research priorities for risk algorithms applications in healthcare settings to improve suicide prevention. Accessed June 10, 2020. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/events/2019/risk-algorithm/index.shtml

- 15.Kessler RC, Warner CH, Ivany C, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Predicting suicides after psychiatric hospitalization in US Army soldiers: the Army Study To Assess Risk and rEsilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(1):49-57. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Stein MB, Petukhova MV, et al. ; Army STARRS Collaborators . Predicting suicides after outpatient mental health visits in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(4):544-551. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon GE, Johnson E, Lawrence JM, et al. Predicting suicide attempts and suicide deaths following outpatient visits using electronic health records. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(10):951-960. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17101167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh CG, Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC. Predicting suicide attempts in adolescents with longitudinal clinical data and machine learning. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(12):1261-1270. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barak-Corren Y, Castro VM, Javitt S, et al. Predicting suicidal behavior from longitudinal electronic health records. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(2):154-162. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16010077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh CG, Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC. Predicting risk of suicide attempts over time through machine learning. Clinical Psychological Science. 2017;5(3):457-469. doi: 10.1177/2167702617691560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gradus JL, Rosellini AJ, Horváth-Puhó E, et al. Prediction of sex-specific suicide risk using machine learning and single-payer health care registry data from Denmark. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(1):25-34. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berrouiguet S, Barrigón ML, Castroman JL, Courtet P, Artés-Rodríguez A, Baca-García E. Combining mobile-health (mHealth) and artificial intelligence (AI) methods to avoid suicide attempts: the Smartcrises study protocol. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):277. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2260-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Q, Zhang-James Y, Barnett EJ, et al. Predicting suicide attempt or suicide death following a visit to psychiatric specialty care: a machine learning study using Swedish national registry data. PLoS Med. 2020;17(11):e1003416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindsell CJ, Stead WW, Johnson KB. Action-informed artificial intelligence—matching the algorithm to the problem. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2141-2142. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKernan LC, Lenert MC, Crofford LJ, Walsh CG. Outpatient engagement and predicted risk of suicide attempts in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019;71(9):1255-1263. doi: 10.1002/acr.23748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isaacman DJ, Burke BL. Utility of the serum C-reactive protein for detection of occult bacterial infection in children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(9):905-909. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.9.905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenert MC, Matheny ME, Walsh CG. Prognostic models will be victims of their own success, unless…. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(12):1645-1650. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. ; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedegaard H, Schoenbaum M, Claassen C, Crosby A, Holland K, Proescholdbell S. Issues in developing a surveillance case definition for nonfatal suicide attempt and intentional self-harm using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coded data. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018;(108):1-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swain RS, Taylor LG, Braver ER, Liu W, Pinheiro SP, Mosholder AD. A systematic review of validated suicide outcome classification in observational studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(5):1636-1649. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roden DM, Pulley JM, Basford MA, et al. Development of a large-scale de-identified DNA biobank to enable personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(3):362-369. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith GCS, Seaman SR, Wood AM, Royston P, White IR. Correcting for optimistic prediction in small data sets. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(3):318-324. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969-1998. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1137-1143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holmberg L, Vickers A. Evaluation of prediction models for decision-making: beyond calibration and discrimination. PLoS Med. 2013;10(7):e1001491. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steyerberg EW, Borsboom GJJM, van Houwelingen HC, Eijkemans MJ, Habbema JDF. Validation and updating of predictive logistic regression models: a study on sample size and shrinkage. Stat Med. 2004;23(16):2567-2586. doi: 10.1002/sim.1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elias J, Heuschmann PU, Schmitt C, et al. Prevalence dependent calibration of a predictive model for nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spiegelhalter DJ. Probabilistic prediction in patient management and clinical trials. Stat Med. 1986;5(5):421-433. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780050506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh C, Hripcsak G. The effects of data sources, cohort selection, and outcome definition on a predictive model of risk of thirty-day hospital readmissions. J Biomed Inform. 2014;52:418-426. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rembold CM. Number needed to screen: development of a statistic for disease screening. BMJ. 1998;317(7154):307-312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7154.307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Passos IC, Ballester P. Positive predictive values and potential success of suicide prediction models. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(8):869. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis SE, Lasko TA, Chen G, Siew ED, Matheny ME. Calibration drift in regression and machine learning models for acute kidney injury. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(6):1052-1061. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis SE, Greevy RA, Fonnesbeck C, Lasko TA, Walsh CG, Matheny ME. A nonparametric updating method to correct clinical prediction model drift. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019;26(12):1448-1457. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocz127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine . The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press; 2007. doi: 10.17226/11903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dickerman BA, Hernán MA. Counterfactual prediction is not only for causal inference. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(7):615-617. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00659-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doshi R, Aseltine RH, Wang F, Schwartz H, Rogers S, Chen K. Illustrating the role of health information exchange in a learning health system: improving the identification and management of suicide risk. Connecticut Medicine. 2018;82(6):327-333. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puchi C, Tyndall B, McPheeters M, Walsh CG. Testing the feasibility of an academic-state partnership to combat the opioid epidemic in Tennessee through predictive analytics. In: Proceedings of the AMIA Annual Symposium; 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Predictive Modeling Details

eReferences.

eTable. Reference Codes From International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Version 10, Clinical Modification