Abstract

Background

The unpredictable trajectory of pediatric advanced heart disease makes prognostication difficult for physicians and informed decision‐making challenging for families. This study evaluated parent and physician understanding of disease burden and prognosis in hospitalized children with advanced heart disease.

Methods and Results

A longitudinal survey study of parents and physicians caring for patients with advanced heart disease age 30 days to 19 years admitted for ≥7 days was performed over a 1‐year period (n=160 pairs). Percentage agreement and weighted kappa statistics were used to assess agreement. Median patient age was 1 year (interquartile range, 1–5), 39% had single‐ventricle lesions, and 37% were in the cardiac intensive care unit. Although 92% of parents reported understanding their child's prognosis “extremely well” or “well,” 28% of physicians thought parents understood the prognosis only “a little,” “somewhat,” or “not at all.” Better parent‐reported prognostic understanding was associated with greater preparedness for their child's medical problems (odds ratio, 4.7; 95% CI, 1.4–21.7, P=0.02). There was poor parent–physician agreement in assessing functional class, symptom burden, and likelihood of limitations in physical activity and learning/behavior; on average, parents were more optimistic. Many parents (47%) but few physicians (6%) expected the child to have normal life expectancy.

Conclusions

Parents and physicians caring for children with advanced heart disease differed in their perspectives regarding prognosis and disease burden. Physicians tended to underestimate the degree of parent‐reported symptom burden. Parents were less likely to expect limitations in physical activity, learning/behavior, and life expectancy. Combined interventions involving patient‐reported outcomes, parent education, and physician communication tools may be beneficial.

Keywords: communication, congenital heart disease, heart failure, pediatrics, prognosis, quality of life

Subject Categories: Congenital Heart Disease, Heart Failure, Pediatrics

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AHD

advanced heart disease

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

This is the first study to evaluate and compare parent and physician understanding of disease burden and prognosis in hospitalized children with cardiac disease.

Parents were less likely than physicians to expect limitations in physical activity, learning/behavior, and life expectancy.

Physicians underestimate the degree of parent‐reported symptom burden.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

The present study identified gaps in communication between parents and physicians regarding key areas of disease status and prognosis.

Combined interventions involving patient‐reported outcomes, parent education, and physician communication tools may be beneficial in improving parent–physician shared understanding.

Significant medical and surgical advances have resulted in a growing population of children surviving longer with advanced heart disease (AHD). 1 , 2 , 3 Despite these improvements, the morbidity for this population remains high, 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 and these children may face major neurodevelopmental challenges that affect quality of life. 9 , 10 Studies to evaluate parent understanding of prognosis for children with AHD have been limited. However, prognostic awareness has been found to critically inform parental decision‐making in the pediatric oncology population. 11 , 12 , 13 Shared decision‐making between parents and physicians should ideally occur in the context of concordant understanding of the child's prognosis. Although the data are limited, previous studies have identified discrepancies between parent and physician expectations about prognosis, 14 , 15 poor preparedness of pediatric cardiologists in predicting life expectancy, 15 and significant variability in communication with families of children with heart disease. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19

The existing literature demonstrates a need for improvement in parent–physician communication, especially related to patient disease burden and prognosis. However, in order to inform the development of interventions to improve communication in this specific population, additional data are needed regarding how parents understand their child's disease and how this compares with physicians. The objective of this study was 2‐fold: (1) to assess parental understanding of disease burden and prognosis; and (2) to evaluate agreement between parents and physicians regarding key aspects of disease burden and prognosis, including symptom burden, likelihood of future limitations in physical activity and learning, and life expectancy. We hypothesized that parents would tend to perceive greater symptom burden as compared with physicians, and would be less likely to expect limitations in future abilities and lifespan.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Design

This is a longitudinal survey study of parents and physicians caring for patients admitted with primary cardiac diagnoses between March 2018 and March 2019 at a single large pediatric heart center. Patient characteristics including demographic and clinical variables were collected by retrospective chart review. The Boston Children's Hospital Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol and survey instrument.

Survey Development and Pilot Phase

The Survey about Caring for Children with Heart Disease (Table S1) was adapted from this group's original bereavement survey of parents of children who died of AHD, 20 which was implemented in a cross‐sectional study of parents of children at 2 large pediatric cardiac centers. The original instrument was pretested to assess content, wording, response burden, cognitive validity, and willingness to participate. The Survey about Caring for Children with Heart Disease was further adapted following input from additional focus groups (including nurses, social workers, physicians, and child life specialists) as well as input from several parents of children with AHD. Questions were primarily closed ended and based on 4‐point or 5‐point Likert scales. The survey addressed the following domains: symptoms, quality of life, understanding of prognosis, quality of care, and communication. The survey and associated documents were also professionally translated into Spanish. All Spanish‐speaking patients were approached with an in‐person or video‐based Spanish interpreter. The Survey about Caring for Children with Heart Disease Physician Survey (Table S2) was developed to include matched questions related to perceptions about patient quality of life, prognostication, and communication.

Participants

Eligible participants included parents and physicians of patients age ≥30 days and ≤19 years admitted for ≥7 days to the general cardiology ward or cardiac intensive care unit with a diagnosis of AHD, defined as the following: single ventricle physiology, pulmonary vein stenosis, pulmonary hypertension or any cardiac diagnosis plus 1 or more of the following: length of stay >30 days, mechanical circulatory support, mechanical ventilation >14 days, ≥3 admissions in past year, or listed for heart transplant (Table 1). 3 Parents were excluded if they could not complete the survey in either English or Spanish.

Table 1.

Study Inclusion Criteria

|

Parents were approached consecutively in person for potential enrollment. The survey was explained in detail and a study letter was provided. Trained research staff administered the surveys in person via iPads. The study iPads were password‐protected, encrypted, and stored in a locked office. A link to the physician survey was then emailed to the provider who the parent identified as the person from whom they received most of their information about their child's heart disease. Although parents most often identified a physician, in 4 cases they identified a nurse practitioner, who was included as “physician” in this study. Consent to participate in the study was assumed if a parent or physician chose to complete the survey. Both a parent and physician must have completed the survey in order for the patient to be included in the final study sample. Medical record review was performed by trained study team members utilizing a standardized algorithm. Cardiac diagnostic information was reviewed by the primary investigator (EDB). A response to at least 50% of survey questions was required in order to be included.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Survey responses were recorded in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure deidentified, password‐protected database. 21 Each patient was assigned a unique study number. Corresponding parent and physician surveys were coded accordingly. Autovalidations and queries were incorporated into the database. Research investigators then reviewed and verified the data for accuracy and completeness. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Associations were examined using the Fisher exact test, χ2 test, and Mantel‐Haenszel test for linear trend. Descriptive statistics of parents and physicians are reported separately as percentage of the total responding to specific questions. When parent–physician responses were compared, percentage agreement with exact 95% CIs was used to report concordance between parent and physician pairs. The percentage of parent–physician pairs with “major disagreement,” which was defined as having answers at opposite ends of the survey response scale, was also calculated. For questions that were administered as a 5‐point Likert Scale, percentage agreement and major disagreement were analyzed using a collapsed 3‐point Likert scale. Functional classification standard 4‐point scales were analyzed in their original form. Weighted kappa statistics were also estimated to evaluate agreement between parents and physicians. Univariate logistic regression models were used to examine the association between patient characteristics and parent‐reported outcomes. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 178 parents approached for inclusion, 18 either declined to participate or did not complete at least 50% of the survey questions. A total of 160 parent–physician pairs were analyzed.

Patient Characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 2. The median patient age at parent enrollment was 1 year (range, 30 days–19 years; interquartile range [IQR], 1–5 years) with the majority of patients (54%) <2 years of age. Just over a third (37%) of patients were in the cardiac intensive care unit at the time of survey. Primary cardiac diagnoses included single ventricle lesions (39%), other congenital heart disease (29%), pulmonary hypertension (12%), pulmonary vein stenosis (9%), and cardiomyopathy/heart transplant (11%). Twenty‐three percent of patients were known to have a genetic syndrome. Median length of stay at study enrollment was 13 days (range, 7–91; IQR 9–31 days) and almost all patients (86%) had undergone a cardiac surgery or catheterization during the survey hospitalization. The median total length of hospitalization in which the survey occurred was 35 days (range, 7–374; IQR, 16–57). Eight percent of patients were awaiting heart transplant at time of enrollment and 6% died during the survey hospitalization. Patients had a median of 30 days of hospitalization at the study institution in the past year.

Table 2.

Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | N=160 |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Age at enrollment, y | |

| <2 | 87 (54%) |

| 2–11 | 55 (34%) |

| >11 | 18 (11%) |

| Female | 76 (48%) |

| Patient location | |

| Cardiology ward | 101 (63%) |

| Cardiac intensive care unit | 59 (37%) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Primary cardiac diagnosis | |

| Single ventricle lesion | 63 (39%) |

| Other congenital heart disease | 46 (29%) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 19 (12%) |

| Pulmonary vein stenosis | 14 (9%) |

| Heart transplant recipient | 9 (6%) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 9 (6%) |

| Age at diagnosis | |

| Prenatal | 105 (67%) |

| First week of life | 35 (22%) |

| >6 mo of age | 18 (11%) |

| Genetic syndrome present | 36 (23%) |

| Burden of disease | |

| Catheterization and/or surgery during hospitalization | 138 (86%) |

| Awaiting heart transplant | 12 (8%) |

| Length of stay at enrollment, d | 13 (9–31) |

| Total length of hospitalization in which survey occurred, d | 35 (16–57) |

| Remained inpatient 1 mo after survey completion | 45 (28%) |

| Death during hospitalization | 10 (6%) |

| Days of hospitalization in past year | 30 (13–47) |

Displayed as n (%) or median (interquartile range).

Parent Characteristics

Parent characteristics are summarized in Table 3. Of the 160 parents, 81% were mothers, 63% had at least a college level education, 72% were White, and 19% identified as Hispanic/Latino.

Table 3.

Parent Characteristics

| Characteristic | N=160 |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 34 (29–39) |

| Relationship to patient* | |

| Mother | 130 (81%) |

| Father | 27 (17%) |

| Race | |

| White | 115 (72%) |

| Black | 12 (8%) |

| Asian | 7 (4%) |

| Other†/unknown | 23 (14%) |

| Ethnicity, Hispanic/Latino | 29 (19%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Less than high school | 8 (5%) |

| High school | 49 (32%) |

| College | 67 (44%) |

| Graduate school | 30 (19%) |

| Married or living with partner | 114 (75%) |

Results displayed as n (%) or median (interquartile range).

Two surveys were completed by both parents and 1 did not specify parental role.

Participants wrote in Latino or Hispanic (14), Asian Indian (1), Middle Eastern (1), Brazilian (1), Spanish Spain (1), or did not specify (5).

Median parental age was 34 years (range, 17–56; IQR, 29–39). Seventy‐five percent were married or living with partners.

Physician Characteristics

Physician characteristics are summarized in Table 4. The 50 participating physicians included cardiologists (58%), cardiac intensivists (10%), cardiac surgeons (12%), and other providers (20%). Cardiologist subspecialties included general cardiology (39%), cardiac imaging (34%), heart failure/transplant (17%), and interventional cardiology (7%). Physicians had a median of 19 years in practice (range, 2–44, IQR, 13–27).

Table 4.

Physician Characteristics

| Characteristic | N=50 |

|---|---|

| Years in practice | 19 (13–27) |

| Years in practice at study institution | 11.5 (6–20) |

| Physician type | |

| Cardiologist | 29 (58%) |

| General cardiology | 9 |

| Cardiac imaging | 10 |

| Heart failure/transplant | 5 |

| Interventional cardiology | 2 |

| Other | 3 |

| Cardiac intensivist | 5 (10%) |

| Cardiac surgeon | 6 (12%) |

| Other | 10 (20%) |

Results displayed as n (%) or median (interquartile range).

Perceived Understanding of Prognosis

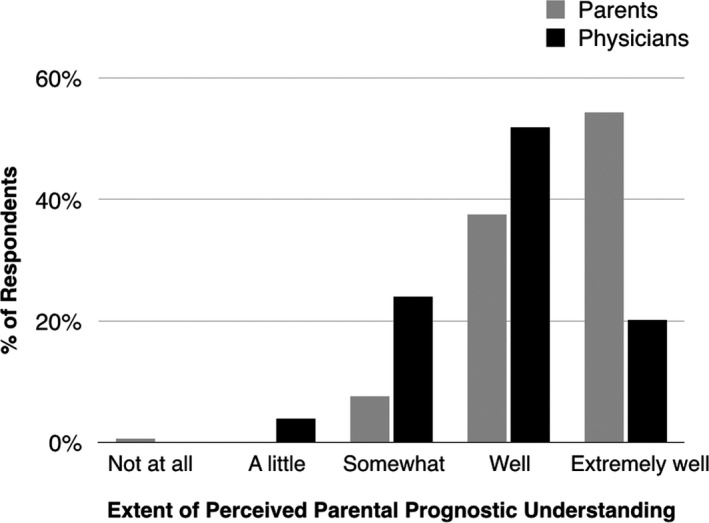

When asked how well they understood their child's prognosis (defined as “the likely course of your child's heart disease”), parents reported that they understood their child's prognosis “extremely well” (54%), “well” (38%), “somewhat” (8%), or “not at all” (<1%) (Figure 1). Parents of children who had undergone cardiac surgery before survey administration during the admission were significantly less likely to report understanding their child's prognosis compared with those who had not undergone cardiac surgery (83% versus 95% reported understanding prognosis “well” or “extremely well,” P=0.016). There were no other significant associations between patient characteristics and parent‐reported understanding of prognosis.

Figure 1. Parent and physician perception of parental prognostic understanding based on responses to: Parent: “How well do you feel that you understand the likely course of your child's heart disease (ie, prognosis)?”; Physician: “How well do you think this patient's family understands their child's prognosis?”.

Although 92% of parents reported that they understood their child's prognosis “extremely well” or “well,” 28% of physicians thought that parents understood the prognosis only “a little” or “somewhat.” No physicians selected “Not at all.”

Fifty‐seven percent of parents reported worrying that their child will get sicker “a lot” or “all of the time.” Compared with physicians, parents more often reported that day‐to‐day management of their child's heart condition affected their ability to discuss prognosis “a great deal” or “a lot” (33% versus 14%). Twenty‐eight percent of parents reported feeling that the care team knew something about the child's prognosis that they did not and 67% of parents answered “Yes” when asked if they would have liked to know more about their child's prognosis.

When asked how well they felt parents understood their child's prognosis, 72% of physicians selected “extremely well” or “well” (Figure 1). When asked to what extent their expectations for prognosis aligned with that of their child's care team, 73% of parents felt that they aligned “a great deal” or “a lot.” Similarly, when physicians were asked, 71% felt that their expectations aligned “a great deal” or “a lot” with those of the parents.

When agreement with respect to understanding of prognosis was assessed between individual parent–physician pairs, 71.0% of pairs showed agreement (Table 5, Figure 2) and only 5 parents (3.2%, 95% CI, 1.1–7.4%) showed major disagreement with their physician counterparts. When there was disagreement, in general physicians underestimated the degree to which parents reported understanding their child's prognosis.

Table 5.

Parent–Physician Agreement in Key Survey Domains

| Survey Domain | % Agreement | 95% CI | κ | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parental understanding of prognosis | 71.0 | 63.6–78.4 | 0.12* | 0.035 |

| Patient functional status | 36.1 | 28.3–44.5 | 0.17 | 0.003 |

| Patient symptom burden | 45.0 | 36.8–55.3 | 0.13 | 0.051 |

| Parental preparedness for child's medical problems | 51.0 | 43.4–59.8 | 0.14 | 0.017 |

| Likelihood of limitations in physical activity | 47.7 | 39.6–55.9 | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Likelihood of limitations in learning/behavior | 27.3 | 20.4–35.2 | –0.15 | 0.013 |

| Likelihood of needing lifelong interventions | 77.9 | 70.5–84.2 | 0.70 | <0.001 |

| Patient life expectancy | 41.3 | 33.0–50.0 | 0.24 | <0.001 |

| Patient inpatient status at 1 mo | 61.3 | 51.2–70.9 | 0.45 | <0.001 |

Kappa statistic is unreliable (paradoxically low in presence of high agreement) when the distribution of responses is highly imbalanced.

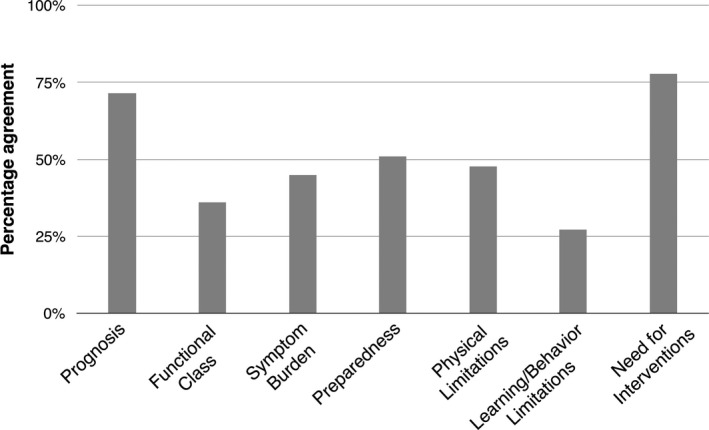

Figure 2. Percentage agreement between individual parent–provider pairs across survey domains.

For questions that were administered as a 5‐point Likert Scale, percentage agreement was analyzed using a collapsed 3‐point Likert scale. Functional class was analyzed in its original 4‐point form. Parents and physicians demonstrated the most concordance with respect to parental understanding of prognosis and likelihood of need for cardiac interventions. The most limited agreement was observed with perception of functional class and likelihood of limitations in learning/behavior.

To assess the individual components that make up prognostic awareness, parents and physicians were asked a series of questions related to preparedness, perceived likelihood of future limitations, and life expectancy. To understand perceptions of baseline disease burden, parents and physicians were asked to describe the child's current functional status and symptom burden.

Functional Status and Symptom Burden

Parents and physicians were asked to answer questions related to symptoms and perceived functional status of the child in the preceding week. In response to the question, “What describes your child's current functional status?,” parents answered: I—no limitation (17%), II—slight limitation (43%), III—marked limitation (27%), and IV—unable to carry on any physical activity without discomfort (14%). Physicians classified the child's functional status as I, II, III, or IV based on either the Modified Ross Heart Failure Class (≤8 years of age) or New York Heart Association Functional Classification (>8 years of age): I (15%), II (45%), III (19%), and IV (21%). There was limited agreement (36.1%) between parents and physicians with regard to functional status (Table 5, Figure 2). Additionally, 6 parent–provider pairs demonstrated major disagreement (ie, 1 selected functional class I when the other selected class IV) (4.2%, 95% CI, 1.5–8.8). Parent/physician agreement with respect to functional status was higher in parents with education beyond high school compared with high school or less (43% versus 20% agreement, P=0.006). There was no association with parent age.

Participants were asked, “Overall, in the past week, to what degree do you feel your/the child is experiencing symptoms related to his/her heart condition?” Just over half of both parents and physicians (56% and 52%, respectively) selected “a great deal” or “a lot” of symptoms. However, there was limited agreement (45.0%) between individual parent–physician pairs regarding degree of symptom burden (Table 5, Figure 2). Moreover, 27 parent–physician pairs (18.1%, 95% CI, 12.2–25.3%) demonstrated major disagreement. When there was disagreement, in general physicians underestimated the degree of parent‐reported symptom burden.

Parents who reported that their child had a functional class of III or IV were significantly more likely to report “a great deal” or “a lot” of symptom burden than parents whose child had a functional class of I or II (odds ratio [OR], 4.6; 95% CI, 2.2–9.5, P<0.001). Seventy‐six percent of parents who reported that their child had worse functional class (III‐IV) perceived “a great deal” or “a lot” of symptoms, compared with 40% of parents of children who reported that their child had a functional class of I or II.

Preparedness

Parents were asked to describe how well prepared they felt for the medical problems their child was experiencing at the time of survey completion. Parents reported feeling “very” (56%), “somewhat” (35%), “a bit” (8%), and “not at all” (1%) prepared. When asked to describe how prepared they perceived the parents to be, physicians reported: “very” (40%), “somewhat” (48%), “a bit” (9%), and “not at all” (3%). There was moderate individual agreement (51.0%) between how prepared the parents reported feeling and how prepared the providers perceived the parents to be (Table 5, Figure 2). Moreover, 17 parents demonstrated major disagreement with physicians (11.1%, 95% CI, 6.6–17.2%). In general, when there was disagreement, parents tended to report feeling more prepared than physicians thought they were.

Better parent‐reported prognostic understanding was associated with greater parent preparedness (“very prepared” versus all other categories) for the medical problems their child was experiencing (OR, 4.7; 95% CI, 1.4–21.7, P=0.02). Fifty‐nine percent of parents who reported understanding their child's prognosis “extremely well” or “well” reported feeling “very prepared” for the medical problems their child was experiencing, compared with 23% of parents with lower levels of prognostic understanding. There were no significant associations between patient characteristics and parental preparedness.

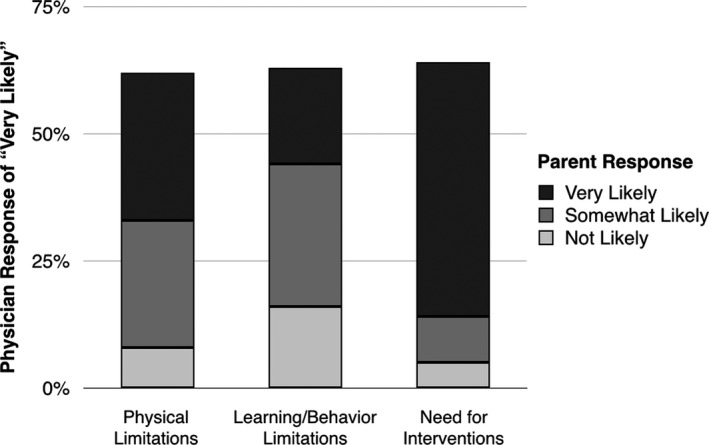

Likelihood of Future Limitations

Parents and physicians were asked to describe their expectations for the child's limitations in physical activity and learning/behavior and need for lifelong cardiac interventions. Parents and physicians reported that it was “very likely” for the child to have limitations in physical activity (34% of parents versus 63% of physicians), limitations in learning/behavior (36% of parents versus 63% of physicians), and need for lifelong interventions (50% of parents versus 65% of physicians). Individual parent–physician pairs were discordant with respect to likelihood of limitations in physical activity (47.7% agreement) and learning/behavior (27.3% agreement) (Table 5, Figures 2 and 3). Parent–physician pairs demonstrated more concordance with respect to likelihood of needing lifelong interventions (77.9% agreement) (Table 5, Figures 2 and 3). In fact, this topic yielded the highest agreement between parents and physicians among all questions on the survey. Parent/physician agreement with respect to need for lifelong intervention was even higher in parents with education above high school compared with high school or less (87% versus 64% agreement, P=0.002). There was no association with parent age.

Figure 3. Parent and physician assessment of likelihood of limitations in physical activity and learning/behavior and likelihood of need for future cardiac interventions.

The y‐axis is the percentages of physicians who selected “very likely” that the child would have limitations in physical activity and learning/behavior and “very likely” to need future interventions. Within each column is the percentage of parents of those patients who responded, “very likely,” “somewhat likely,” and “not at all likely” to the same questions. Compared with parents, physicians were more likely to expect limitations in physical activity and learning/behavior and more likely to expect that future interventions would be necessary.

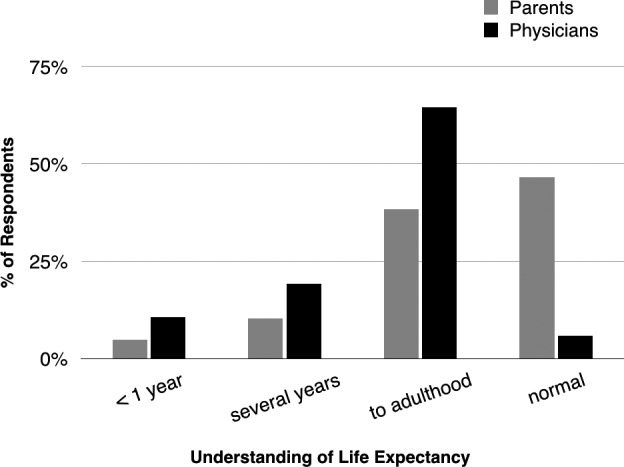

Life Expectancy

Parents and physicians were asked, “What is your current understanding of how long your child/this patient will live?” Many parents (46.6%) but few physicians (5.9%) expected their child/patient to have a normal life expectancy (Figure 4). Providers predicted survival of no more than “several years” for 39 subjects; for 22 (56%) of these, the parents expected a normal life span and/or survival into adulthood. There was discordance between individual parent–provider pairs (41.3% agreement, Table 5), with parents generally considering their child to have a longer life expectancy than the provider did.

Figure 4. Parent and provider unpaired responses to the question “What is your current understanding of how long your child/this patient will live?”.

Many parents (47%) but few physicians (6%) expected their child/patient to have a normal life expectancy.

Prediction of Inpatient Status at 1 Month

Parents and physicians were also asked how likely they thought it was that their child/patient would still be in the hospital 1 month from the survey date. In general, both parents and providers more accurately predicted which children would be out of the hospital than they predicted who would still be in hospital. At 1 month from the survey date, 45 (28.1%) of the 160 patients were still in the hospital. Parents and physicians who selected that it would be "very likely" for the child to remain inpatient (28.1% and 28.7%, respectively) were correct in 40% and 60% of cases, respectively. Parents and physicians who selected "not likely" (46.3% and 50.5%) were correct in 78% and 94% of cases, respectively. There was 61.3% agreement between parent and physician pairs (Table 5). When there was disagreement, in general parents believed that their child would be out of the hospital earlier than the physician did.

Discussion

This is the first study to assess understanding of disease burden and prognosis among parents and providers caring for children with AHD. Significant discrepancies emerged between parents and physicians with respect to assessment of disease burden. In addition, although parents report that they understand prognosis well, discrepancies exist between parents and physicians caring for children with AHD with respect to understanding the individual components of prognosis, including life expectancy and likelihood of future limitations.

Prognostication is difficult for physicians and families caring for children with AHD, 3 , 14 in part because of the unpredictable disease trajectory, 3 , 22 which often requires unanticipated intensive care unit stays 23 and frequent surgical or catheter‐based interventions. A national survey of pediatric cardiologists revealed that the majority feel inadequately prepared to prognosticate life expectancy. 15 Even when physicians do have an accurate understanding of prognosis, they may not effectively communicate this with the patient and family. Moreover, there is significant variability in communication with and counseling of families of children with heart disease with respect to diagnosis and prognosis. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Additionally, pediatric cardiologists' counseling approaches and overall demeanor have been shown to influence how parents perceive their child's chance of survival and their request for a second opinion. 16 Given this, open communication and shared understanding between parents and physicians is critical to help parents prepare for the likelihood of intermittent decompensations, functional limitations, and need for reintervention.

Most parents reported that they understood their child's prognosis “well” or “extremely well.” This could reflect that parents do indeed have a reasonably good understanding of prognosis but that prognosis itself is uncertain. Moreover, two thirds of parents reported that they would like more information about their child's prognosis. This is consistent with a prior study demonstrating that parents of children with congenital heart disease would like to receive more education and counseling in the prenatal and newborn periods than cardiologists perceive is desired. 17 Parents of children who had undergone cardiac surgery during the survey hospitalization reported significantly lower perceived understanding of prognosis. This may reflect that the day‐to‐day management of their child's heart condition in the postoperative period makes it difficult to focus on long‐term prognosis. This reinforces the importance of having prognostic conversations at times of stability before scheduled interventions or acute decompensations. Paired parent–physician agreement regarding parent understanding of prognosis was better than concordance found in other survey areas. However, given that discrepancies were found between the 2 groups with respect to the individual components that make up prognostic awareness, parent–physician agreement with respect to overall parent prognostic understanding may be a poor indicator of their actual agreement on the factors that contribute to a child's long‐term prognosis, life expectancy, and quality of life.

There was poor concordance between individual parent–physician pairs with respect to perception of disease burden. Physicians tended to underestimate the degree of parent‐reported symptom burden. As survival for children with AHD has improved, there is greater focus on improving functional status and thereby quality of life. Children with cardiovascular disease have been demonstrated to have lower quality of life as compared with healthy children, and severity of cardiovascular disease tends to correspond with degree of limitation in quality of life. 24 , 25 One study asked pediatric cardiac clinicians to review clinical summaries and predict health‐related quality of life. They found poor agreement between individual clinicians as well as poor agreement between average clinician‐predicted health‐related quality of life scores and those reported by patients and parent‐proxies. 26 Clinicians were generally noted to overestimate health‐related quality of life compared with patients and parent‐proxies, which is consistent with what we found in our study. Without patient‐reported data in our current study, it was not possible to determine which group was more accurate in their assessment of disease burden. Studies from the pediatric oncology literature have demonstrated the feasibility and value of using patient‐reported outcomes to assess health‐related quality of life. 27 , 28 , 29 A similar tool could be quite valuable if applied and studied in the pediatric cardiac population, especially if combined with parent and physician reports.

Parent preparedness for medical issues was also examined as a factor related to understanding of prognosis. We found that parents tended to report feeling more prepared than physicians thought they were. Additionally, better parent‐reported prognostic understanding was associated with greater parent preparedness (“very prepared” versus all other categories) for the medical problems their child was experiencing. This suggests that if we can improve parent understanding of prognosis, we can improve how prepared parents feel for the medical problems their child is facing. Compared with parents, physicians were more likely to perceive future limitations in all surveyed areas, including physical activity, learning/behavior, and need for lifelong cardiac‐directed interventions. There was greatest agreement between the groups with respect to likelihood of needing interventions, which may reflect the focus on cardiac surgical and catheterization‐based procedures in counseling of families, especially in the single‐ventricle population where staged palliation is typically reviewed at time of prenatal diagnosis. Physicians may be more likely than parents to understand that frequent interventions will be associated with prolonged hospital stays and unforeseen complications, which may cause deconditioning and periods of missed school, thereby causing limitations in physical activity and learning/behavior.

Parents and physicians also demonstrated significant discordance with respect to life expectancy. Almost half of parents but only 6% of physicians expected the child to have a normal life expectancy. This discrepancy may reflect a greater focus during parent–physician interactions on more immediate issues related to patient care, rather than on long‐term prognosis. Additionally, parents may be answering based on their hopes rather than true expectations. Data from future longitudinal studies would be useful to compare expected versus actual survival in this patient population. However, given that long‐term survival data show significant limitations in life expectancy for many of the cardiac diagnoses included in this study, 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 there already appears to be room for improvement in communication of this information to families.

To assess short‐term prognostic accuracy, parents and physicians were asked how likely they thought it would be for the child to remain in the inpatient setting 1 month from the survey date. Physicians were more accurate than parents in their prediction. When there was disagreement, parents were more likely to predict discharge before 1 month. This suggests that physicians are either not communicating their assessment of anticipated hospitalization duration, not communicating their assessment in a way that parents can understand, or that parental optimism/hope influences parents' prediction. A recent study in the pediatric oncology population demonstrated that parent prognostic accuracy was related to the way in which they value and receive prognostic information from physicians. 38 Most parents reported both “explicit” sources of prognostic information (ie, formal conversations at diagnosis) and “implicit” sources (ie, “a general sense of how my child's oncologist seems to feel my child is doing”) to be informative. However, those who valued implicit information demonstrated lower (more optimistic) prognostic accuracy. Given these findings, the authors suggested that physicians incorporate explicit factual information about prognosis into their ongoing conversations with parents to improve parent understanding and avoid overly optimistic parental expectations.

There are several limitations to the present study. The sample was limited to a single institution and consisted of predominantly English‐speaking White or Hispanic mothers. The inclusion criteria focused on hospitalized children with AHD only, making the functional status and symptom burden results difficult to generalize to an outpatient cardiology population. Just over half of children included in the study were under 2 years of age, which may influence generalizability. However, patient age was not found to be significantly associated with any parent‐reported outcomes. Additionally, the study institution is a major referral center and we recognize that some patients may have received prior cardiac treatment elsewhere. Parents who are able and motivated to seek treatment at a second institution may have different perspectives compared with those who remain at a local center. Moreover, parents may receive counseling and prognostic information from multiple providers, which could influence their understanding of prognosis. The study is also subject to the limitations inherent to parent‐ and physician‐reported measures. Lastly, univariate logistic regression models were used to examine the association between patient characteristics and parent‐reported outcomes and therefore potential confounders were not assessed.

Conclusions

This is the first study to assess prognostic understanding among parents and physicians of children with AHD. Overall, our results identify gaps in communication between parents and physicians regarding key areas of disease status and prognosis. Parents and physicians caring for children with AHD differed in their perspectives regarding prognosis and disease burden. Physicians tended to underestimate the degree of parent‐reported symptom burden. Parents were less likely than physicians to expect limitations in physical activity, learning/behavior, and life expectancy. Better parent‐reported prognostic understanding was associated with greater reported preparedness for their child's medical problems. Combined interventions involving patient‐reported outcomes, parent education, and physician communication tools may be beneficial.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Advanced Cardiac Therapies Research and Education Fund and the Dorothy and Howard Dulman Fund.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S2

Acknowledgments

We thank the parents and providers who participated in this study for sharing their experiences and perspectives.

(J Am Heart Assoc.2021;10:e018488. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018488.)

Supplementary Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.120.018488

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

References

- 1. Rossano JW, Kim JJ, Decker JA, Price JF, Zafar F, Graves DE, Morales DLS, Heinle JS, Bozkurt B, Towbin JA, et al. Prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of heart failure‐related hospitalizations in children in the United States: a population‐based study. J Card Fail. 2012;18:459–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osterman MJK, Kochanek KD, MacDorman MF, Strobino DM, Guyer B. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2012–2013. Pediatrics. 2015;135:1115–1125. 10.1542/peds.2015-0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Morell E, Moynihan K, Wolfe J, Blume ED. Palliative care and paediatric cardiology: current evidence and future directions. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3:502–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Oster ME, Lee KA, Honein MA, Riehle‐Colarusso T, Shin M, Correa A. Temporal trends in survival among infants with critical congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1502–e1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Newburger JW, Sleeper LA, Gaynor JW, Hollenbeck‐Pringle D, Frommelt PC, Li JS, Mahle WT, Williams IA, Atz AM, Burns KM, et al. Transplant‐free survival and interventions at 6 years in the SVR trial. Circulation. 2018;137:2246–2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Laussen PC. Modes and causes of death in pediatric cardiac intensive care: digging deeper. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17:461–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morell E, Wolfe J, Scheurer M, Thiagarajan R, Morin C, Beke DM, Smoot L, Cheng H, Gauvreau K, Blume ED. Patterns of care at end of life in children with advanced heart disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:745–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lasa JJ, Gaies M, Bush L, Zhang W, Banerjee M, Alten JA, Butts RJ, Cabrera AG, Checchia PA, Elhoff J, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of acute decompensated heart failure in children. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13:e006101. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, Peacock G, Gerdes M, Gaynor JW, Mussatto KA, Uzark K, Goldberg CS, Johnson WH, et al.; American Heart Association Congenital Heart Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and Stroke Council . Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126:1143–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Newburger JW, Sleeper LA, Bellinger DC, Goldberg CS, Tabbutt S, Lu M, Mussatto KA, Williams IA, Gustafson KE, Mital S, et al. Early developmental outcome in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome and related anomalies: the single ventricle reconstruction trial. Circulation. 2012;125:2081–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mack JW, Cook EF, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: parental optimism and the parent‐physician interaction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1357–1362. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenberg AR, Orellana L, Kang TI, Geyer JR, Feudtner C, Dussel V, Wolfe J. Differences in parent‐provider concordance regarding prognosis and goals of care among children with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3005–3011. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mack JW, Cronin AM, Uno H, Shusterman S, Twist CJ, Bagatell R, Rosenberg A, Marachelian A, Granger MM, Glade Bender J, et al. Unrealistic parental expectations for cure in poor‐prognosis childhood cancer. Cancer. 2020;126:416–424. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.32553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Balkin EM, Wolfe J, Ziniel SI, Lang P, Thiagarajan R, Dillis S, Fynn‐Thompson F, Blume ED. Physician and parent perceptions of prognosis and end‐of‐life experience in children with advanced heart disease. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:318–323. DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balkin EM, Kirkpatrick JN, Kaufman B, Swetz KM, Sleeper LA, Wolfe J, Blume ED. Pediatric cardiology provider attitudes about palliative care: a multicenter survey study. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017;38:1324–1331. DOI: 10.1007/s00246-017-1663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hilton‐Kamm D, Sklansky M, Chang RK. How not to tell parents about their child’s new diagnosis of congenital heart disease: an internet survey of 841 parents. Pediatr Cardiol. 2014;35:239–252. DOI: 10.1007/s00246-013-0765-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Arya B, Glickstein JS, Levasseur SM, Williams IA. Parents of children with congenital heart disease prefer more information than cardiologists provide. Congenit Heart Dis. 2013;8:78–85. DOI: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2012.00706.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kon AA, Ackerson L, Lo B. How pediatricians counsel parents when no “best‐choice” management exists: lessons to be learned from hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:436–441. DOI: 10.1001/archpedi.158.5.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walsh MJ, Verghese GR, Ferguson ME, Fino NF, Goldberg DJ, Owens ST, Pinto N, Zyblewski SC, Quartermain MD. Counseling practices for fetal hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017;38:946–958. DOI: 10.1007/s00246-017-1601-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blume ED, Balkin EM, Aiyagari R, Ziniel S, Beke DM, Thiagarajan R, Taylor L, Kulik T, Pituch K, Wolfe J. Parental perspectives on suffering and quality of life at end‐of‐life in children with advanced heart disease: an exploratory study*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:336–342. DOI: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sames‐Dolzer E, Gierlinger G, Kreuzer M, Schrempf J, Gitter R, Prandstetter C, Tulzer G, Mair R. Unplanned cardiac reoperations and interventions during long‐term follow‐up after the Norwood procedure†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;51:1044–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Penk JS, Loke Y‐H, Waloff KR, Frank LH, Stockwell DC, Spaeder MC, Berger JT. Unplanned admissions to a pediatric cardiac critical care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Uzark K, Jones K, Slusher J, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Quality of life in children with heart disease as perceived by children and parents. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1060–e1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mellion K, Uzark K, Cassedy A, Drotar D, Wernovsky G, Newburger JW, Mahony L, Mussatto K, Cohen M, Limbers C, et al. Health‐related quality of life outcomes in children and adolescents with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr. 2014;164:781–788.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Costello JM, Mussatto K, Cassedy A, Wray J, Mahony L, Teele SA, Brown KL, Franklin RC, Wernovsky G, Marino BS. Prediction by clinicians of quality of life for children and adolescents with cardiac disease. J Pediatr. 2015;166:679–683.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dussel V, Orellana L, Soto N, Chen K, Ullrich C, Kang TI, Geyer JR, Feudtner C, Wolfe J. Feasibility of conducting a palliative care randomized controlled trial in children with advanced cancer: assessment of the PediQUEST study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:1059–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wolfe J, Orellana L, Ullrich C, Cook EF, Kang TI, Rosenberg A, Geyer R, Feudtner C, Dussel V. Symptoms and distress in children with advanced cancer: prospective patient‐reported outcomes from the PediQUEST study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1928–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wolfe J, Orellana L, Cook EF, Ullrich C, Kang T, Geyer JR, Feudtner C, Weeks JC, Dussel V. Improving the care of children with advanced cancer by using an electronic patient‐reported feedback intervention: results from the PediQUEST randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1119–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu MY, Zielonka B, Snarr BS, Zhang X, Gaynor JW, Rychik J. Longitudinal assessment of outcome from prenatal diagnosis through Fontan operation for over 500 fetuses with single ventricle‐type congenital heart disease: the Philadelphia Fetus‐to‐Fontan Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009145. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tweddell JS, Hoffman GM, Mussatto KA, Fedderly RT, Berger S, Jaquiss RDB, Ghanayem NS, Frisbee SJ, Litwin SB. Improved survival of patients undergoing palliation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome: lessons learned from 115 consecutive patients. Circulation. 2002;106:182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khairy P, Fernandes SM, Mayer JE, Triedman JK, Walsh EP, Lock JE, Landzberg MJ. Long‐term survival, modes of death, and predictors of mortality in patients with Fontan surgery. Circulation. 2008;117:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McGuirk SP, Griselli M, Stumper OF, Rumball EM, Miller P, Dhillon R, de Giovanni JV, Wright JG, Barron DJ, Brawn WJ. Staged surgical management of hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a single institution 12 year experience. Heart. 2006;92:364–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goldfarb SB, Levvey BJ, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC, Khush K, Kucheryavaya AY, Lund LH, Meiser B, Rossano JW, Yusen RD, et al. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twentieth pediatric lung and heart‐lung transplantation report—2017; focus theme: allograft ischemic time. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2017;36:1070–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Singh RK, Canter CE, Shi L, Colan SD, Dodd DA, Everitt MD, Hsu DT, Jefferies JL, Kantor PF, Pahl E, et al. Survival without cardiac transplantation among children with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2663–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moledina S, Hislop AA, Foster H, Schulze‐Neick I, Haworth SG. Childhood idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: a national cohort study. Heart. 2010;96:1401–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thiwanka Wijeratne D, Lajkosz K, Brogly SB, Diane Lougheed M, Jiang L, Housin A, Barber D, Johnson A, Doliszny KM, Archer SL. Increasing incidence and prevalence of World Health Organization Groups 1 to 4 pulmonary hypertension: a population‐based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e003973. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.003973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW. How parents of children with cancer learn about their children’s prognosis. Pediatrics. 2018;141:e20172241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S2