Abstract

Background

Neutrophils are thought to be short‐lived first responders to tissue injuries such as myocardial infarction (MI), but little is known about their diversification or dynamics.

Methods and Results

We permanently ligated the left anterior descending coronary arteries of mice and performed single‐cell RNA sequencing and analysis of >28 000 neutrophil transcriptomes isolated from the heart, peripheral blood, and bone marrow of mice on days 1 to 4 after MI or at steady‐state. Unsupervised clustering of cardiac neutrophils revealed 5 major subsets, 3 of which originated in the bone marrow, including a late‐emerging granulocyte expressing SiglecF, a marker classically used to define eosinophils. SiglecFHI neutrophils represented ≈25% of neutrophils on day 1 and grew to account for >50% of neutrophils by day 4 post‐MI. Validation studies using quantitative polymerase chain reaction of fluorescent‐activated cell sorter sorted Ly6G+SiglecFHI and Ly6G+SiglecFLO neutrophils confirmed the distinct nature of these populations. To confirm that the cells were neutrophils rather than eosinophils, we infarcted GATA‐deficient mice (∆dblGATA) and observed similar quantities of infiltrating Ly6G+SiglecFHI cells despite marked reductions of conventional eosinophils. In contrast to other neutrophil subsets, Ly6G+SiglecFHI neutrophils expressed high levels of Myc‐regulated genes, which are associated with longevity and are consistent with the persistence of this population on day 4 after MI.

Conclusions

Overall, our data provide a spatial and temporal atlas of neutrophil specialization in response to MI and reveal a dynamic proinflammatory cardiac Ly6G+SigF+(Myc+NFϰB+) neutrophil that has been overlooked because of negative selection.

Keywords: granulopoiesis, heart, myocardial infarction, neutrophil maturity, neutrophils, siglecF, single‐cell RNA sequencing

Subject Categories: Basic Science Research, Inflammation, Myocardial Infarction

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- DEGs

differentially expressed genes

- I/R

ischemia–reperfusion

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappa‐light‐chain‐enhancer of activated B cells

- scRNA‐seq

single‐cell RNA‐sequencing

- SigF

siglecF

- TAC

transaortic constriction

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Our data provide a temporal atlas of neutrophil specialization from the bone marrow through the blood to the heart after myocardial infarction in mice.

We find a late‐emerging SiglecFHI cardiac neutrophil that expresses high levels of Myc‐regulated and pro‐inflammatory genes.

SiglecFHI neutrophils are present in multiple cardiac injury models including ischemia–reperfusion and chronic pressure overload.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Our findings motivate additional investigations to validate dynamics in humans and explore the diagnostic and therapeutic utility of quantifying neutrophil subsets after myocardial infarction.

Myocardial infarction (MI) incites an acute inflammatory response, leading to rapid mobilization of neutrophils to the site of injury. 1 , 2 Within hours, neutrophils infiltrate the infarcted tissue, where they recruit and activate additional leukocytes, generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), and release granules containing myeloperoxidase and various proteases involved in extracellular matrix remodeling. 3 , 4 These functions are generally considered to be detrimental in the context of MI, but more recent findings have also suggested a role for neutrophils in resolving inflammation and facilitating repair. 5

Neutrophils and other granulocytes are replenished in the bone marrow (BM) through granulopoiesis, wherein hematopoietic progenitors undergo differentiation along neutrophilic, eosinophilic, or basophilic lineages and develop into fully mature granulocytes. 6 This process occurs under complex transcriptional regulation including repression of the transcription factor c‐Myc by C/EBPα. 7 Terminally differentiated neutrophils are then retained in the BM until signaled by the local stromal environment to exit into circulation, at which point they can be recruited towards sites of injury or infection. 8 , 9 , 10

Conventionally, neutrophils have been viewed as a homogeneous population of short‐lived first responders; their role in the inflammatory response to MI is often studied during the immediate aftermath of the injury (ie, up to 1–2 days post‐MI) after which the immune landscape is thought to be overtaken by monocytes and macrophages. 3 While distinct neutrophil subsets have recently been identified using single‐cell techniques in settings of cancer 11 and allergic inflammation, 12 comparatively little is known about neutrophil diversity in cardiac inflammation. A previous report suggested that neutrophils exhibit time‐dependent N1/N2 polarization after MI based on dichotomous expression of pro‐inflammatory (Ccl3, Ccl5, and Il1b) and anti‐inflammatory markers (Arg1, Cd206, and Il10), but did so using ensemble techniques and a candidate gene approach. 13 As such, the full functional diversity and temporal dynamics of cardiac neutrophils remained incompletely characterized until recently. 14 , 15

Here, we utilize single‐cell transcriptomics to examine heterogeneity of pre‐ and postinfarct neutrophils. By correlating neutrophil transcriptomes from the heart, peripheral blood, and BM, we generate a comprehensive map of neutrophil subsets as they evolve between tissues and over time. We identify a late‐stage SiglecFHI neutrophil subset, validate that it is not an eosinophil, perform detailed single‐cell transcriptomic comparisons between it and other cardiac neutrophil subsets, and record its emergence in multiple models of cardiac injury. Our results reveal an unexpectedly rich functional diversity among MI‐recruited neutrophils in vivo and indicate that neutrophils remain transcriptionally dynamic beyond the immediate response to injury. Contemporaneous with our work, convergent and mutually confirmatory results surrounding SiglecFHI neutrophils in MI were independently reported and published. 14 , 15 Our respective findings validate the discovery while using independent approaches to investigating this population. Collectively, these works now present a substantially sharpened, unified image of neutrophil diversification in cardiac inflammation.

Methods

All data and materials have been made publicly available at the NCBI GEO database and can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ under accession no. GSE157244.

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the Subcommittee on Animal Research Care at UC San Diego or Massachusetts General Hospital. Mice were maintained in a pathogen‐free environment of the UC San Diego or Massachusetts General Hospital animal facilities. Adult male C57BL/6J (Stock No. 000664) and C.129S1(B6)‐Gata1tm6Sho/J (∆dbl‐GATA, Stock No. 005653) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. All experiments were carried out in 10‐ to 14‐week‐old animals using age‐matched groups with no randomization. Surgeries were performed in a blinded manner except when confounded by discernible differences in coat color.

Murine Permanent Ligation, Ischemia Reperfusion, and Transaortic Constriction

For permanent ligation, ischemia‐reperfusion (I/R), and transverse aortic constriction surgeries, mice were intubated and ventilated with 2% isoflurane. After exposing the heart via thoracotomy at the fourth left intercostal space, the left anterior descending coronary artery was permanently ligated with an 8–0 nylon monofilament suture. For I/R injury, the left anterior descending coronary artery was instead occluded for 30 minutes to induce myocardial ischemia, after which the ligature was released to allow reperfusion. The thorax was closed with a 5–0 suture. Mice were administered buprenorphine for analgesia on the day of surgery and twice daily thereafter for 72 hours. For transverse aortic constriction, the chest cavity was opened by a small incision at the level of the first intercostal space. After isolation of the aortic arch, an 8–0 Prolene suture was placed around the aorta and a 27G needle was laced in between. The needle was immediately removed to produce an aorta with a stenotic lumen. The chest cavity was then closed with one 6–0 nylon suture and all layers of muscle and skin were closed with 6–0 continuous absorbable and nylon sutures, respectively.

Tissue Harvest and Processing

Heart

Heart tissue was collected by incising the right atrium and perfusing PBS into the left ventricular apex to prevent blood contamination; cardiac tissue was then removed. To obtain single‐cell suspensions for flow cytometric analysis or FACS sorting, hearts were finely minced with scissors and enzymatically digested for 1 hour under continuous agitation in 450 U/mL collagenase I, 125 U/mL collagenase XI, 60 U/mL DNase I, and 60 U/mL hyaluronidase (Sigma Aldrich) for 1 hour at 37°C, then passed through a 40 µm nylon mesh cell strainer in FACS buffer (PBS with 2.5% BSA) for enumeration by flow cytometry. For single‐cell RNA‐Seq, the enzymatic digestion was limited to 45 minutes to minimize transcript degradation.

Bone Marrow, Blood, and Spleen

Mouse femurs and tibias were harvested, and BM was flushed with ice‐cold PBS. The flow‐through was strained through a 40‐µm nylon mesh. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and transferred into EDTA‐containing tubes (Sigma‐Aldrich). Spleens were removed and passed through a 40‐µm cell strainer with fluorescent‐activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer. All samples were then treated with red blood cell lysis buffer (BioLegend) for 5 minutes on ice.

Flow Cytometry and FACS Sorting

Cell suspensions generated from processed tissue were stained with antibodies in the dark at 4°C in FACS buffer. A complete list of antibodies used in this study is included below. 4′6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) staining was used to exclude dead cells. Neutrophils were identified as (DAPI/B220/CD49b/CD90.2/NK1.1/Ter119)low, (CD45.2/CD11b/Ly6G)high. Eosinophils were identified as (DAPI/B220/CD49b/CD90.2/NK1.1/Ter119/Ly6G/F4/80)low, (CD45.2/CD11b/SiglecF)high. Flow cytometry was performed on a SONY MA900 cell sorter, and data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Ter119 (BioLegend, clone TER‐119)

B220 (BioLegend, clone RA3‐6B2)

CD49b (BioLegend, clone DX5)

CD90.2 (BioLegend, clone 53‐2.1)

NK1.1 (BioLegend, clone PK136)

CD45.2 (BioLegend, clone 104)

CD11b (BioLegend, clone M1/70)

F4/80 (BioLegend, clone BM8)

Ly6C (BioLegend, clone HK1.4 or BD Bioscience, clone AL‐21)

Ly6G (BioLegend, clone 1A8)

SiglecF (BD Bioscience, clone E50‐2440 or BioLegend, clone S17007L)

Quantitative Real‐Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from FACS‐sorted cells using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen) and cDNA was synthesized using the High‐Capacity RNA‐to‐cDNA kit (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer's instructions. TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems) were used to quantify the following target genes: (Gapdh: Mm99999915_g1, Retnlg: Mm00731489_s1, Ccl6: Mm01302419_m1, Slpi: Mm00441530_g1, Lrg1: Mm01278767_m1, Siglecf: Mm00523987_m1, Ppia: Mm02342430_g1, Tnf: Mm00443258_m1, Icam1: Mm00516023_m1, Snrpg: Mm01183645_g1, Npm1: Mm02391781_g1). Relative changes were normalized to Gapdh mRNA using the 2−∆∆CT method. Outliers were identified and removed using Grubbs' test (α=0.05) in GraphPad Prism.

Single‐Cell RNA Sequencing and Analysis

Single‐cell RNA‐Seq (scRNA‐seq) was performed via microfluidic droplet‐based encapsulation, barcoding, and library preparation (inDrop and 10X Genomics) as previously described. Paired end sequencing was performed on an Illumina Hiseq 2500 and Hiseq 4000 instrument. Low‐level analysis, including demultiplexing, mapping to a reference transcriptome (Ensembl Release 85—GRCm38.p5), and eliminating redundant unique molecular identifiers, was conducted with inDrops software (URL: https://github.com/indrops/indrops) (accessed April 2017) or 10X CellRanger pipeline. All subsequent scRNA‐seq analyses were conducted using the Seurat R package (v3.1) as detailed below.

Total transcript count for each cell was scaled to 10 000 molecules, and ribosomal and mitochondrial reads were removed. Raw counts for each gene were normalized to cell‐specific transcript count and log‐transformed. Cells with between 200 and 4000 unique genes and <5% mitochondrial counts were retained for further analysis. Highly variable genes were identified with the FindVariableFeatures method by selecting 4000 genes with the greatest feature variance after variance‐stabilizing transformation.

Reference‐based integration of scRNA‐seq data sets utilizing canonical correlation analysis was performed to enable harmonized clustering across platforms, conditions, and tissue compartments. After scaling and centering expression values for each variable gene, dimensional reduction was performed on integrated data using principal component analysis and cells were clustered according to the Seurat standard workflow. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between clusters were determined using a Wilcoxon rank sum test. Subclustering was performed by serially subsetting particular cell‐type clusters, identifying a new set of DEGs within the subset, rescaling their counts, and reclustering the subset based on newly determined DEGs. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) was used to visualize data in 2D space.

For functional enrichment analyses, DEGs were filtered for significant P values (P<0.01) and run through gProfiler (URL: https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/gost) or ranked by average log‐fold change and analyzed using the gene‐set enrichment analyses PreRanked tool. 16 , 17

scRNA‐Seq Scores

To determine the number of genes considered within each score, we evaluated differences in score between cluster 1 (RetnlgHI) and indicated clusters as a function of number of genes. The minimum number of genes was selected such that 99.5% of cells within an indicated cluster had positive difference. Raw counts were summed within each cell, divided by total counts, and multiplied by 10 000 to generate scores.

For calculation of Myc score, 200 genes from the HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V2 gene set were retrieved from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) to generate a scoring list (39).

Any genes simultaneously present in the SiglecF scoring gene list were removed.

Spearman's Rank Correlation Coefficients

For Spearman's rank correlation analysis, expression of all variable genes were averaged in each subset being compared and ranked by subset‐defining DEGs (scaled data) to create a comparator ranked gene list. A Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (ρ) for each cell was calculated by (where d is the distance between gene ranks, n is number of genes) and averaged within subsets.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software. All data are represented as mean values±SEM unless indicated otherwise. A statistical method was not used to predetermine sample size. For comparisons of the quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction data and scores, a Mann–Whitney U test or 2‐tailed t test with Welch's correction was used to determine statistical significance. All analyses were unpaired. P<0.05 were considered significant and are indicated by asterisks as follows: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

Results

scRNA‐seq Reveals Distinct MI‐Induced Cardiac Neutrophil Heterogeneity

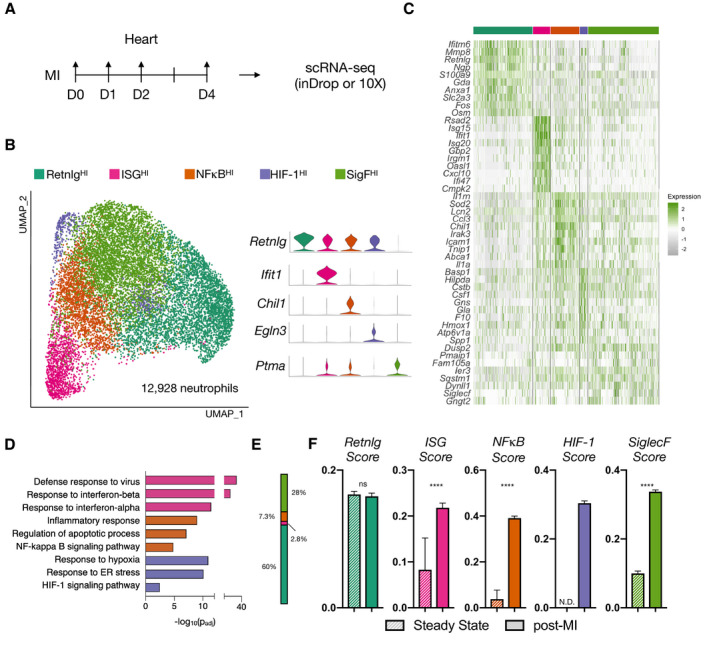

To define neutrophil heterogeneity after MI, we performed permanent ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery in mice and harvested heart tissue on days 1, 2, and 4 after MI (D1, D2, and D4) and compared with nonoperated controls (D0). After removing dead cells, erythrocytes, and doublets by flow cytometry (DAPI−Ter119−), single cells were processed through the commercial 10X Genomics scRNA‐seq pipeline or custom inDrop barcoding platform (Figure S1A). After demultiplexing and mapping to a reference genome, the resulting counts matrices were integrated using Seurat v3 to harmonize samples and reduce batch effects. Cells were first clustered at low resolution to identify major cell types. Neutrophils were defined by the expression of canonical neutrophil markers S100a8, S100a9, Csf3r, Cxcr2, Mmp9, Csf1, and Il1r2, consistent with previous reports (Figure S1B). 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 Neutrophil barcodes were then subset from the original unintegrated counts matrices, and reintegrated to produce a harmonized data set consisting of ≈13 000 neutrophils across D0‐D4, containing a median of 1048 transcripts per cell (Figure S2). Unsupervised clustering revealed 5 cardiac neutrophil subsets, respectively defined by (1) high expression of Retnlg (RetnlgHI), (2) interferon‐stimulated genes (ISGHI), (3) genes regulated by nuclear factor kappa‐light‐chain‐enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) (NFκBHI), (4) genes regulated by hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF‐1HI), and (5) the classically eosinophilic surface marker SiglecF (SigFHI) (Figure 1A through 1D). All clusters were similarly represented between single‐cell barcoding platforms showing that integration sufficiently mitigated batch effects (Figure S3A and S3B). Since scRNA‐seq is highly susceptible to the "drop‐out” phenomenon in which a gene is detected in 1 cell but is lowly or not expressed in a similar cell, we constructed several cluster scores representing these biological processes by summing the top DEGs within each cluster (Figure S4, see Methods). We captured ≈150 neutrophils from the steady‐state mouse with membership mostly in RetnlgHI and SigFHI clusters (Figure 1E). We determined that these cells were likely blood contaminates based upon quantitative similarity to blood neutrophils (detailed later). We took advantage of this to compare transcriptomes of steady‐state blood neutrophils with post‐MI cardiac neutrophils. All scores were significantly elevated after MI with the exception of the Retnlg score (Figure 1F). Together, these results suggest that subsets associated with type I interferons, NFκB, and HIF‐1, as well as an uncharacterized SiglecF‐associated transcriptional program, were all significantly elevated in the heart neutrophils after MI.

Figure 1. Single‐cell RNA sequencing reveals distinct MI‐induced cardiac neutrophil heterogeneity.

A, Experimental design. B, UMAP of pre‐ and postinfarct (D1, D2, D4; n=4) integrated neutrophils (12 928 neutrophils), color‐coded by cluster with marker genes shown in violin plots. C, Heatmap displaying top 10 DEGs. D, Cluster‐specific gene set enrichment analysis (Gprofiler). E, Fractional membership of pre‐infarct neutrophils. F, Subset‐specific scores applied to pre‐ and postinfarct data. Data shown are mean±SEM of single‐cell values (****P<0.0001; Mann–Whitney test). ER indicates endoplasmic reticulum; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; HIF, hypoxia‐inducible factor; MI, myocardial infarction; and UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

SigF Expression Marks a Late‐Stage Granulocyte

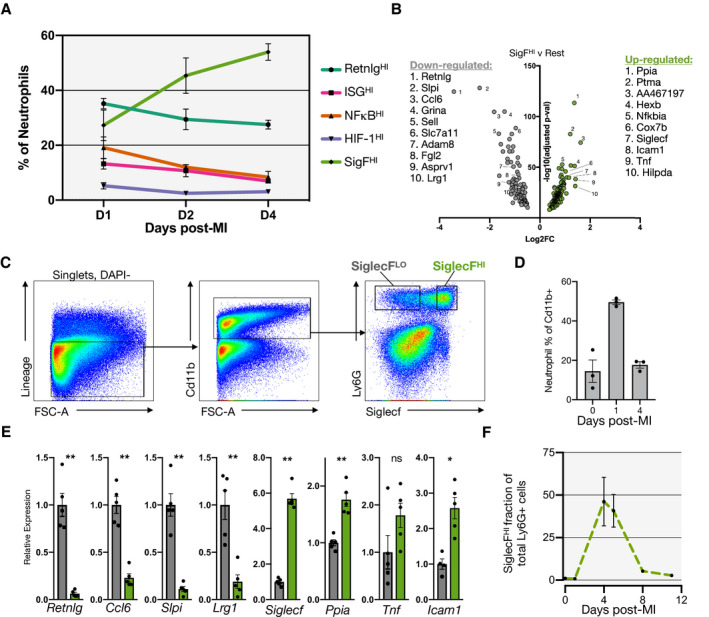

We next explored the temporal dynamics of the SigF neutrophil population. By quantifying cluster membership across time, we found that the SigFHI cluster represented 27.2±11% (mean±SD) of neutrophils on D1 but increased to 54±6% of neutrophils by D4. Meanwhile, other clusters steadily declined from D1 to D4 (Figure 2A). Using a volcano plot, we compared transcriptional profiles of the SigFHI cluster with the other neutrophil clusters and identified increased expression of Ppia, Ptma, Icam1, Tnf, and the classically eosinophilic surface marker Siglecf as well as decreased expression of genes including Retnlg, Slpi, Ccl6, Grina, and Sell (Figure 2B). This particular transcriptional profile bears resemblance to that of previously reported aged circulating neutrophils (ICAM1HICD62L(Sell)LO), which exhibit a hyperinflammatory phenotype characterized by overactive ROS production, increased phagocytosis and NETosis, and enhanced vascular adhesion. 24 , 25 , 26 In combination with its delayed appearance in the heart, this suggests SigFHI neutrophils may represent an aged neutrophil subset. To determine whether SigF expression was increased at the surface protein level, we isolated leukocytes from the infarcted heart on post‐MI D4, immunostained them for Cd11b, Ly6G, and SigF, enumerated them by flow cytometry, and sorted them for quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction analysis. Flow cytometric analysis revealed canonical neutrophils (Cd11b+Ly6G+SigFLO), canonical eosinophils (Cd11b+Ly6G‐SigFHI), and a double‐positive Cd11b+Ly6G+SigFHI granulocyte (Figure 2C) with a scatter profile similar to that of its SigFLO counterpart (Figure S5). We FACS sorted Cd11b+Ly6G+ cells into SigFHI and SigFLO populations and compared their gene expression profiles using bulk quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction, which validated the scRNA‐seq results. SigFHI granulocytes expressed significantly higher levels of Siglecf, Ppia, and Icam1 while SigFLO cells expressed higher levels of Retnlg, Ccl6, Slpi, and Lrg1 (Figure 2D). To define the dynamics of this population, we analyzed the Cd11b+Ly6G+ cells across time and enumerated the evolving percentage of SigFHI cells, which validated the scRNA‐Seq findings and showed that Ly6G+SigF+ expression peaked on D4 after MI and nearly resolved by D8 after MI (Figure 2E). These data define and validate the existence of a late‐stage Cd11b+Ly6G+SigF+ granulocyte and show how it can be recognized by single‐cell transcriptomics or by flow cytometry using anti‐SigF immunostaining.

Figure 2. Siglecf expression marks a late‐stage cardiac granulocyte.

A, Fractional membership of scRNA‐seq neutrophil subsets across time after MI. B, Volcano plot of DEGs of SigFHI vs rest of clusters (Wilcoxon rank test). C, Flow cytometry of leukocytes isolated on D4‐post MI and immunostained for Cd11b, Ly6G, and SiglecF. D, Neutrophil quantification as a fraction of total Cd11b+ cells in the heart at steady state and on D1 and D4 post‐MI. E, qPCR results comparing SiglecFLO (gray) and SiglecFHI (green) granulocytes (n=5). F, Fractional membership of SiglecFHI neutrophils as function of time post‐MI (n=3). Data shown are mean±SEM. (**P<0.01, *P<0.05; Student t test). DEGs indicates differentially expressed genes; MI, myocardial infarction; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; and scRNA‐seq, single‐cell RNA‐sequencing.

Ly6G+SigFHI Granulocytes Are Neutrophils, Not Eosinophils

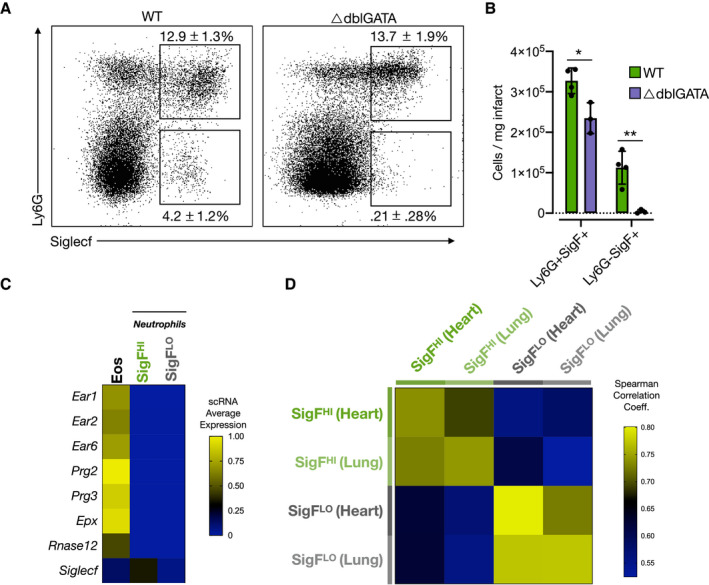

Since SigF is viewed as a prototypical surface marker of eosinophils, studies focusing on neutrophils commonly exclude SigFHI cells by flow cytometry or CYTOF. 27 , 28 We considered the possibility that neutrophils expressing SigF have gone undiscovered and unexplored because of exclusion before analysis. Therefore, we investigated whether Ly6G+SigFHI granulocytes within the infarcted heart are neutrophils or eosinophils. We performed permanent ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery in eosinophil‐deficient mice (∆dblGATA), 29 and isolated leukocytes from the infarcted heart on D4 post‐MI. We then immunostained the resulting cell suspension with fluorescently labeled anti‐Cd11b, anti‐Ly6G, and anti‐SigF antibodies and enumerated granulocyte populations by flow cytometry. As expected, the Ly6GSigFHI (eosinophils) population declined from 11.2±3.8×104 cells/mg heart (2.44±1.05% of Cd11b+ cells) to 0.38±0.46×104 cells/mg heart (0.58±0.35% of Cd11b+ cells) in WT and ∆dblGATA mice, respectively. In contrast to a near‐complete ablation of eosinophils, the quantity of Ly6G+SigFHI cells only slightly decreased from 32.7±3.1×104 cells/mg heart to 23.5±3.8×104 cells/mg heart in WT and ∆dblGATA mice, suggesting that this double‐positive population is not a classical GATA‐dependent eosinophil (Figure 3A and 3B).

Figure 3. Ly6G+SigFHI granulocytes are neutrophils, not eosinophils.

A, Flow cytometry data of leukocytes isolated from ΔdblGATA mice on D4‐post MI and immunostained for Cd11b, Ly6G, and SiglecF (% of Cd11b cells; mean±SD). B, Quantification of classically defined neutrophils, eosinophils, and Ly6G+SiglecFHI granulocytes. C, Heatmap showing relative gene expression of canonical eosinophil genes in SigFHI and SigFLO neutrophils and eosinophils (Han et al, 2018 30 ). D, Spearman rank correlation analysis showing similarity of SigFHI and SigFLO neutrophils of present study to previously published lung cancer model. 11 MI indicates myocardial infarction; scRNA, single‐cell RNA; SigF, siglecf; SigFHI, siglecf high; and WT, wild‐type. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, Student's t test.

To verify that Ly6GHISigFHI granulocytes captured by scRNA‐seq represented a subset of neutrophils rather than eosinophils, we compared their single‐cell transcriptomes with those of eosinophils identified in a previously published report. 30 To do so, we combined granulocytes from our D4 infarcted hearts with eosinophils extracted from a published and annotated BM scRNA data set, which were defined by expression of a number of canonically eosinophilic genes (Prg2, Prg3, Epx, Ear1, Ear2, and Ear6). Relative to both SigFHI and SigFLO granulocytes of the present study, eosinophils expressed significantly higher levels of several eosinophil granule‐ and RNAases‐associated genes such as eosinophil peroxidase (Epx), eosinophil‐associated ribonucleases (Ear1, Ear2, Ear6, and Rnase12), and eosinophil major basic proteins (Prg2 and Prg3) (Figure 3C). 31 , 32 Ear1, Ear2, and Epx reportedly decrease in expression as eosinophils mature; however, we also found little to no expression of these markers in SigFHI neutrophils isolated from the BM or blood (Figure S6). Furthermore, SigFHI neutrophils have been previously reported in a murine model of lung cancer. 30 To determine whether the SigFHI neutrophils from the infarcted heart mirror those identified in cancer, we compared SigFHI and SigFLO neutrophil subsets in published scRNA‐seq data of neutrophils isolated from tumor‐bearing lungs with their corresponding subsets in a D4 post‐MI sample using Spearman rank correlation analysis (Figure 3D). This confirmed that cardiac SigFHI neutrophils present after MI indeed exhibit transcriptional similarity to the SigFHI neutrophils characterized in lung cancer. Taken together, these data indicate that SigFHI granulocytes identified by flow cytometry and single‐cell RNA sequencing are neutrophils rather than eosinophils.

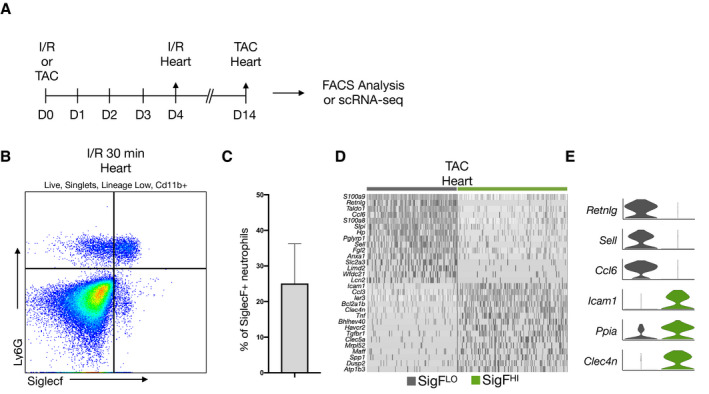

SiglecF+ Neutrophils Are Found in the Heart After I/R and Chronic Pressure Overload

Permanent ligation is often criticized as an imperfect model of ischemic heart injury because it does not reflect the reperfusion injury that follows percutaneous revascularization in humans. We therefore tested whether SigFHI neutrophils were also present after I/R (Figure 4A). Indeed, we found 25.1±19.2% of Cd11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils were SigFHI on D4 following 30 minutes of I/R (Figure 4B and 4C).

Figure 4. SigFHI neutrophils emerge in ischemia–reperfusion and TAC‐induced pressure overload models.

A, Workflow for I/R flow cytometry (n=3) and TAC scRNA‐seq (n=2) experiments. B, Flow cytometry data of leukocytes isolated from the heart on Day 4 post‐I/R and stained for DAPI, Cd11b, Ly6g, and SiglecF. C, Enumeration of SiglecFHI neutrophils as a percentage of total Cd11b+Ly6G+ neutrophils. D, Heatmap of SiglecFLO and SiglecFHI neutrophils, isolated from the heart 14 days after TAC surgery. Top DEGs of each subset are displayed. E, Violin plots displaying expression of top markers for each subset from D. DAPI indicates 4′6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; I/R, ischemia–reperfusion; scRNA‐seq, single‐cell RNA‐sequencing; and TAC, transaortic constriction.

Pressure overload is a model of chronic cardiac injury that can incite fibrosis and an inflammatory response involving cardiac infiltration by leukocytes. 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 We performed transverse aortic constriction to induce pressure overload hypertrophy, collected heart tissue 12 days after surgery, performed scRNA‐Seq, and bioinformatically isolated neutrophils as detailed above (Figure 4A). While the overall prevalence of neutrophils was low, neutrophils spontaneously clustered into dichotomous subsets defined by similar marker genes to those identified after MI (RetnlgHISigFLO or RetnlgLOSigFHI) (Figure 4D and 4E). Taken together, our data suggest that SiglecFHI neutrophils can be found in both acute ischemic and chronic nonischemic injuries of the heart.

SigFHI Neutrophils Are Uniquely Myc‐Recovered and NFκB‐Activated Compared With SigFLO Neutrophils

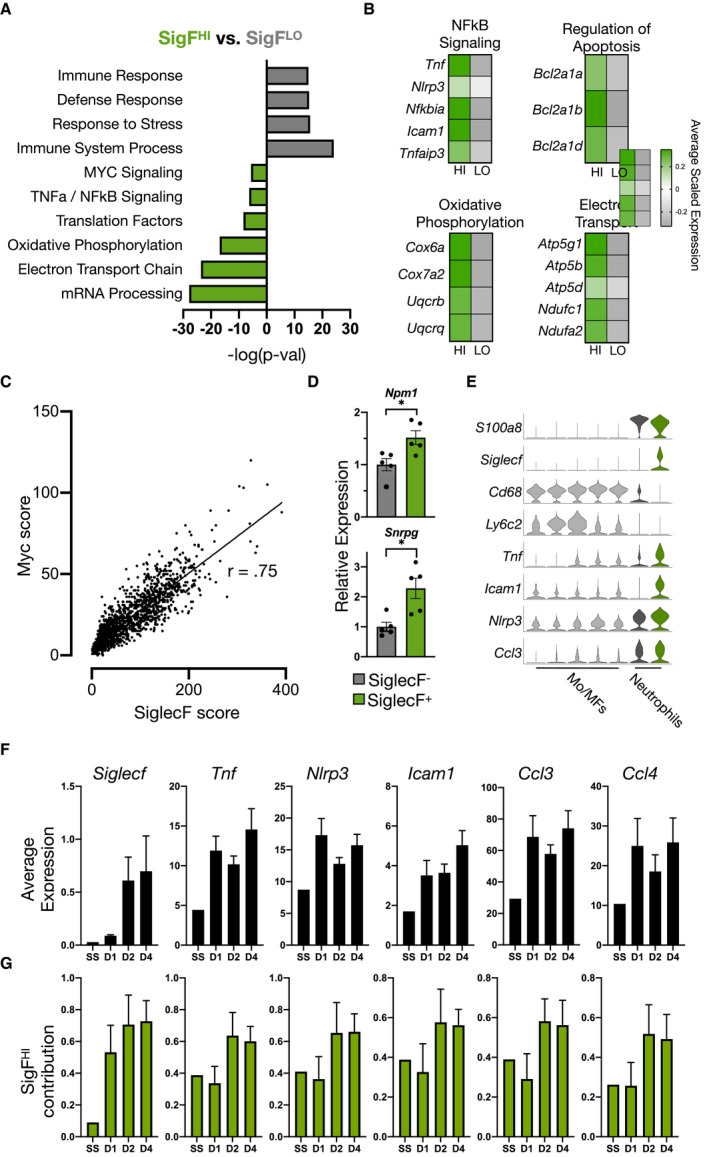

To explore the functional differences between SigFHI and SigFLO neutrophils, we performed gene‐set enrichment analyses on DEGs from D4 post‐MI samples (see Table S1 for complete list of DEGs). SigFHI neutrophils were highly enriched for genes associated with Myc signaling, mRNA processing, electron transport chain activity, nuclear factor‐κB (NFκB) signaling, and oxidative phosphorylation (Figure 5A and 5B).

Figure 5. SigFHI neutrophils are uniquely MYC‐recovered and account for late‐phase NFϰB dynamics.

A, Functional enrichment analysis of SigFHI and SigFLO subsets using gProfiler and MSigDB. B, Heatmaps comparing average scaled gene expression in SigFHI and SigFLO neutrophils. C, Scatterplot of SiglecF score vs Myc score in neutrophils isolated from the heart D4 post‐MI. Correlation coefficient r=0.75. D, qPCR results of Myc‐target genes in Ly6G+SiglecFHI and Ly6G+SiglecFLO neutrophils FACS sorted from digested cardiac tissue 4 days post‐MI. E, Violin plots of neutrophil marker genes (S100a8 and Siglecf), monocyte and macrophage marker genes (Ly6c2 and Cd68), and NFκB‐regulated genes (Tnf, Icam1, Nlrp3, and Ccl3). F, Average expression (by scRNA‐seq) of Siglecf and candidate NFκB‐regulated genes as a function of time post‐MI (N=1 at steady‐state, N=4 for post‐MI samples; mean±SEM). G, Relative contribution of SigFHI neutrophils to total gene expression shown as a fraction of 1. FACS indicates fluorescent‐activated cell sorter; MF, macrophage; MI, myocardial infarction; Mo, monocyte; NFκB, nuclear factor kappa‐light‐chain‐enhancer of activated B cells; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; scRNA‐seq, single‐cell RNA‐sequencing; and SigFHI, siglecf high. *P<0.01, Student's t test (D).

Of note, gene‐set enrichment analyses indicated that SigFHI neutrophils selectively overexpressed downstream targets of Myc, a transcription factor and proto‐oncogene involved in regulating apoptosis, proliferation, and metabolism. 37 Within the BM, myelopoiesis is modulated via reciprocal control of Myc by regulatory factor C/EBPa, with Myc repression driving myeloid progenitors towards terminal neutrophil differentiation. 38 Thus, while other hematopoietic lineages retain a moderate level of Myc activity to support cell survival, division, and greater transcriptional activity, 39 , 40 mature neutrophils are thought to possess near‐undetectable Myc levels. 41 , 42 We were, therefore, surprised to find that Myc targets were significantly overexpressed in terminally differentiated SigFHI neutrophils. To explore the expression of Myc‐regulated genes across neutrophil subsets, we constructed a Myc score by summing normalized expression levels of 200 Myc downstream targets retrieved from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) Hallmark gene set. 43 Applying this score to cardiac neutrophil subsets revealed that the Myc score increased monotonically with increasing SiglecF score (Figure 5C). The observation that SigFHI neutrophils possessed significantly higher Myc scores compared with SigFLO neutrophils was validated by FACS sorting of the 2 subsets and quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction of canonical Myc target genes (Npm1, Snrpg) (Figure 5D). To position these findings within the broader context of Myc regulation during granulopoiesis and confirm validity of Myc scoring, we performed scRNA‐seq on BM cells isolated on D1 post‐MI (Figure S7A). From these data, we identified several distinct cell types along the granulocytic differentiation trajectory including myeloid progenitors (MP), neutrophil progenitors (FcnbHI neutrophils), immature neutrophils (CampHI neutrophils), and mature neutrophils (RetnlgHI neutrophils). 44 As expected, all cells present in the data set were universally high in Myc score with the exception of the neutrophil lineage where the Myc score decreased substantially along the maturation axis from MP to RetnlgHI neutrophils (Figure S7B). Comparison of Myc score in the BM verus heart showed that SigFHi neutrophils in the heart recover a level of Myc activity between that of neutrophil precursors and immature neutrophils found in the BM (Figure S7C and S7D). Given that Myc is heavily involved in survival signaling, these findings further support the notion that SigFHI neutrophils may possess greater longevity relative to their SigFLO counterparts.

The NFκB family of proteins comprises key mediators of innate and adaptive immunity. 45 They consist of 5 inducible DNA‐binding proteins that form hetero‐ or homodimers and induce expression of a multitude of genes involved in several aspects of inflammation including recruitment, proliferation, and cell survival. 45 , 46 , 47 SigFHI neutrophils were enriched for several directly‐NFκB‐regulated genes including tumor necrosis factor‐α (Tnf), inflammasome machinery Nlrp3, and NFκB‐negative feedback genes, Nfkbia and Tnfaip3 (Figure 5B). Plotting NFκB score against the Retnlg‐Siglecf score ratio revealed preferential expression of NFκB target genes in SigFHI cells in agreement with gene‐set enrichment analysis (Figure S8A). To further explore their functional significance, we subset and reclustered SigFHI cells, which revealed a distinct subpopulation characterized by numerous directly NFκB‐regulated marker genes (Figure S8B through S8D). Since NFκB‐signaling in monocytes and macrophages has been extensively studied, 48 , 49 we directly compared single‐cell transcriptomes of monocytes and macrophages with neutrophils, all isolated from the same cardiac tissue on D4 post‐MI. Tnf, Icam1, Nlrp3, and Ccl3 (MIP‐1α) were significantly elevated in SigFHI neutrophils relative to all monocyte and macrophage subsets (Figure 5E).

Tnf and other pro‐inflammatory genes had been previously shown to peak on D1 post‐MI in neutrophils. 13 We therefore explored the possibility that SigFHI neutrophils, which peak in relative abundance on D4‐post MI, contribute towards unrecognized late‐phase NFκB‐signaling. Average Siglecf expression, as measured by scRNA‐seq, increased monotonically from D1 to D4 post‐MI, as expected. In contrast, the average expression of several pro‐inflammatory NFκB‐regulated genes (Tnf, Nlrp3, Icam1, Ccl3, and Ccl4) appeared to follow a decreasing trend from D1 to D2 but departed from this trend on D4 post‐MI (Figure 5F). Because this coincided with the peak abundance of the SigFHI subset, we explored the relative contribution of SigFHI neutrophils to total expression of these genes; this was calculated by summing the expression of each gene for all neutrophils at the various time points, and computing the proportion of this total, which originated from SigFHI neutrophils. SigFHI neutrophils accounted for ≈30% of the total gene expression on D1 and >50% on D2 and D4 post‐MI (Figure 5G). Taken together, these data demonstrate previously unrecognized NFκB‐signaling dynamics in post‐MI neutrophils.

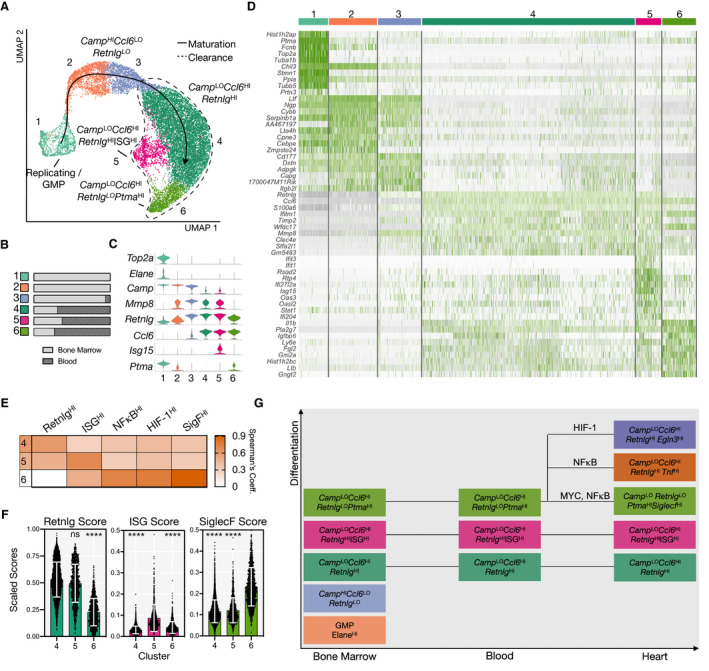

RetnlgHI, ISGHI, and SigFHI Neutrophils Originate in the Bone Marrow

To determine the origins of the cardiac neutrophil subsets, we collected peripheral blood and flushed BM tissue before MI (D0) or on days 1, 2, and 4 after MI (D1, D2, D4), gated on DAPI−Ter119−, and performed the scRNA‐seq pipeline as described above (Figure S9A). Once identified, barcodes of cells expressing neutrophil marker genes were subset from the unintegrated counts matrices and reintegrated, which yielded 15 839 neutrophils. Unsupervised clustering identified 6 continuous subsets, which we ordered from immature to mature neutrophils in agreement with previously reported (Figure 6A, indicated by solid arrow). 44 Bone marrow neutrophils were present in all clusters, indicating that integration was sufficient to identify similar cells between tissue compartments (Figure S9B and S9C). Clusters 1 to 3 represented early neutrophils because they were almost entirely unique to the BM (Figure 6B) and constitutively expressed high levels of secondary granule‐associated genes (Ngp, Ltf) and cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (Camp) (Figure 6C and 6D). Cluster 1 expressed high levels of genes associated with cell cycling (Top2a, Tuba1b, and Tubb5) and primary granules (Elane and Fcnb) (Figure 6C and 6D). Peripheral blood neutrophils represented >50% of clusters 4, 5, and 6 (Figure 6B) and expressed chemokine Ccl6 and collagenase Mmp8 (Figure 6C and 6D). Retnlg, which was highly expressed in all heart subsets with the exception of SigFHI neutrophils (Figure 1B), steadily increased in expression from clusters 1 to 5, but decreased in cluster 6 corresponding with the emergence of several genes associated with SigFHI neutrophils, such as Ptma, Ppia, and Gngt2 (Figure 6C and 6D). Cluster 5 was characterized by high expression of interferon‐stimulated genes such as Ifit1, Ifit3, and Oasl1 (Figure 6C and 6D).

Figure 6. RetnlgHI, ISGHI, and SigFHI neutrophils have correlates in BM and blood.

A, UMAP of integrated neutrophils and neutrophil progenitors isolated from BM and peripheral blood of mice with (D1, D2, D4) and without MI. Clusters ordered along maturation axis as indicated by solid line arrow. Dashed area shows clusters found in blood. B, Fractional representation of tissue by cluster. C, Violin plot showing marker genes for each cluster. D, Heatmap showing top 10 DEGs per cluster. E, Spearman's rank coefficients showing similarity of clusters 4, 5, and 6 to cardiac subsets. F, Retnlg, ISG, and SiglecF scores, as defined previously, applied to clusters 4, 5, and 6. G, Diagram showing evolution of neutrophil differentiation across tissue compartments. BM indicates bone marrow; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; and UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection.

Finally, we tested the hypothesis that infarct neutrophil subsets began specialization within the BM before arriving at the heart. Indeed, Spearman's rank correlation analysis found that clusters 4, 5, and 6 demonstrated subset‐specific similarity to RetnlgHI, ISGHI, and SigFHI neutrophils, respectively (Figure 6E). Siglecf, though minimally expressed, steadily increased along the maturation axis with maximum expression in cluster 6. We observed a similar trend with numerous genes associated with SigFHI neutrophils, suggesting that SigFHI neutrophils of the heart represent a continuation of granulopoiesis in the BM and blood (Figure S9D). Indeed, subset‐specific scores defined above confirmed that clusters 4, 5, and 6 had elevated Retnlg, ISG, and Siglecf scores, respectively (Figure 6F). We did not observe distinct SigF+ neutrophils in BM, blood, or spleen before or after MI in mice by FACS analysis in agreement with single‐cell transcriptomic findings. Taken together, these data demonstrate that neutrophil diversity observed in the heart originates within the BM, but acquisition of the full SigF phenotype (including surface SigF expression) occurs locally in the heart.

Discussion

Though neutrophil diversity in cancer has been studied in depth, much remains unknown on the subject in the setting of cardiac inflammation. Here, we present a single‐cell transcriptomic landscape of neutrophils within the infarcted heart and elucidate the temporal dynamics of neutrophil composition over the first 4 days following MI. Our data capture unexpected functional variety among cardiac neutrophils, previously obscured by ensemble measurement techniques. We identify 5 major time‐dependent subtypes of neutrophils in the heart, including a population of late‐emerging SigFHI neutrophils transcriptionally similar to a subset of neutrophils found in murine lung cancer, but previously uncharacterized in the setting of cardiac inflammation. We validate the existence of SigFHI neutrophils by flow cytometry; we then trace the emergence of the SigF signature to the BM and observe a transitional state of its acquisition in peripheral blood.

Our findings surrounding the origins of SigFHI neutrophils suggest both some level of early fate specification as well as local activation within the heart; while a small number of neutrophils begin displaying a SigF‐associated gene signature as early as within the BM compartment, we find that infiltration of ischemic cardiac tissue is required to develop the full SigF‐associated transcriptional fingerprint and acquire surface protein expression of SigF. The increased variability of SiglecF expression in the I/R model suggests that SigF expression is dependent on the extent of ischemia because of the technical difficulty of the model. The mechanistic basis for this activation, as well as whether all neutrophils have underlying potential to become SigFHI, remains to be investigated.

Though Myc activity is generally low among neutrophils because of its suppression by C/EBPα during granulocytic differentiation, we observed that SigFHI neutrophils are uniquely Myc‐recovered. Because SigFHI neutrophils simultaneously exhibit activation of NFκB—another transcriptional program involved in survival signaling and resistance to apoptosis—this raises the possibility that SigFHI neutrophils are a comparatively long‐lived population within the infarct. Its delayed emergence within the heart and expression of various markers previously observed on aged neutrophils in circulation (Cd62L LO Icam1 HI) further align with this notion.

Functional enrichment analysis also revealed that SigFHI neutrophils overexpress genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation, despite mature neutrophils being classically thought to rely almost entirely on glycolysis to fulfill metabolic demands. 50 A similar phenomenon of metabolic switching was recently described in tumor‐elicited neutrophils generating ROS under conditions of limited glucose availability, suggesting that SigFHI neutrophils exhibit hyperactive ROS production. The increase in ROS productivity, as well as upregulation of electron transport chain and mRNA processing‐associated genes, suggests that SigFHI neutrophils may engage in neutrophil extracellular trap formation.

One important limitation inherent to all single‐cell studies (the present work included) is that the number of subsets that emerge from clustering is not an absolute quantity; rather, it is highly dependent upon bioinformatic analysis parameters including clustering resolution. The cardiac neutrophil subsets enumerated here exhibit clear upregulation of various transcriptional programs, and the SigF neutrophil subset was validated to be distinct at the surface protein and bulk RNA levels. As such, we reasonably concluded that the populations observed by scRNA‐seq likely represent true transcriptomic diversity; however, future functional studies are necessary to accurately determine the biological significance of these subsets.

Although our results clarify the heterogeneity of neutrophils in MI with temporal resolution, they also raise several questions for future studies to address. What role do SigcFHI neutrophils play within the infarct? It remains unclear whether or not their presence is favorable or detrimental in the context of MI. A recent study showed that anti‐SigF‐treated mice displayed impaired left ventricular function and increased ventricular dilation after MI, suggesting that SigFHI neutrophils are beneficial to myocardium repair, though the results are confounded by the simultaneous depletion of eosinophils. 51 Given that SigFHI neutrophils appear within the infarct at a relatively later time point, coinciding with the arrival of monocytes, it is possible that they are involved in the recruitment or signaling of monocytes and macrophages. Future work will need to examine the consequences of neutrophil‐specific perturbations on the global immune landscape and cardiac function.

Sources of Funding

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R00HL129168, DP2AR075321, King; T32HL105373, Calcagno) and the American Heart Association (17IRG33410543, King; 14FTF20380185, Aguirre).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Table S1

Figures S1–S9

Acknowledgments

We thank the Single Cell Core at Harvard Medical School and the Institute of Genomic Medicine at UC San Diego for technical assistance.

(J Am Heart Assoc.2021;10:e019019. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.019019.)

Supplementary Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.120.019019

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 13.

References

- 1. Blankesteijn WM, Creemers E, Lutgens E, Cleutjens JP, Daemen MJ, Smits JF. Dynamics of cardiac wound healing following myocardial infarction: observations in genetically altered mice. Acta Physiol Scand. 2001;173:75–82. DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cleutjens JP, Blankesteijn WM, Daemen MJ, Smits JF. The infarcted myocardium: simply dead tissue, or a lively target for therapeutic interventions. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;44:232–241. DOI: 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo JL, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3037–3047. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frangogiannis NG, Smith CW, Entman ML. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:31–47. DOI: 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Horckmans M, Ring L, Duchene J, Santovito D, Schloss MJ, Drechsler M, Weber C, Soehnlein O, Steffens S. Neutrophils orchestrate post‐myocardial infarction healing by polarizing macrophages towards a reparative phenotype. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lawrence SM, Corriden R, Nizet V. The ontogeny of a neutrophil: mechanisms of granulopoiesis and homeostasis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2018;82:e00057 ‐17. DOI: 10.1128/MMBR.00057-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scott LM, Civin CI, Rorth P, Friedman AD. A novel temporal expression pattern of three C/EBP family members in differentiating myelomonocytic cells. Blood. 1992;80:1725–1735. DOI: 10.1182/blood.V80.7.1725.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martin C, Burdon PC, Bridger G, Gutierrez‐Ramos JC, Williams TJ, Rankin SM. Chemokines acting via CXCR2 and CXCR4 control the release of neutrophils from the bone marrow and their return following senescence. Immunity. 2003;19:583–593. DOI: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katayama Y, Battista M, Kao WM, Hidalgo A, Peired AJ, Thomas SA, Frenette PS. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell. 2006;124:407–421. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heidt T, Sager HB, Courties G, Dutta P, Iwamoto Y, Zaltsman A, von zur Muhlen C, Bode C, Fricchione GL, Denninger J, et al. Chronic variable stress activates hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2014;20:754–758. DOI: 10.1038/nm.3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Zilionis R, Da Silva MJ, Bos SA, Courties G, Rickelt S, Severe N, Baryawno N, Faget J, et al. Osteoblasts remotely supply lung tumors with cancer‐promoting SiglecF(high) neutrophils. Science. 2017;358:eaal5081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Radermecker C, Sabatel C, Vanwinge C, Ruscitti C, Maréchal P, Perin F, Schyns J, Rocks N, Toussaint M, Cataldo D, et al. Locally instructed CXCR4(hi) neutrophils trigger environment‐driven allergic asthma through the release of neutrophil extracellular traps. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:1444–1455. DOI: 10.1038/s41590-019-0496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma Y, Yabluchanskiy A, Iyer RP, Cannon PL, Flynn ER, Jung M, Henry J, Cates CA, Deleon‐Pennell KY, Lindsey ML. Temporal neutrophil polarization following myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;110:51–61. DOI: 10.1093/cvr/cvw024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vafadarnejad E, Rizzo G, Krampert L, Arampatzi P, Arias‐Loza A‐P, Nazzal Y, Rizakou A, Knochenhauer T, Bandi SR, Nugroho VA, et al. Dynamics of cardiac neutrophil diversity in murine myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2020;127:e232–e249. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Calcagno DM, Ng RP Jr, Toomu A, Zhang C, Huang K, Aguirre AD, Weissleder R, Daniels LB, Fu Z, King KR. The myeloid type i interferon response to myocardial infarction begins in bone marrow and is regulated by Nrf2‐activated macrophages. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eaaz1974. DOI: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge‐based approach for interpreting genome‐wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raudvere U, Kolberg L, Kuzmin I, Arak T, Adler P, Peterson H, Vilo J. g:Profiler: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and conversions of gene lists (2019 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W191–W198. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkz369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hessian PA, Edgeworth J, Hogg N. MRP‐8 and MRP‐14, two abundant Ca(2+)‐binding proteins of neutrophils and monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;53:197–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ryckman C, Vandal K, Rouleau P, Talbot M, Tessier PA. Proinflammatory activities of S100: proteins S100A8, S100A9, and S100A8/A9 induce neutrophil chemotaxis and adhesion. J Immunol. 2003;170:3233–3242. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cacalano G, Lee J, Kikly K, Ryan AM, Pitts‐Meek S, Hultgren B, Wood WI, Moore MW. Neutrophil and b cell expansion in mice that lack the murine IL‐8 receptor homolog. Science. 1994;265:682–684. DOI: 10.1126/science.8036519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martin P, Palmer G, Vigne S, Lamacchia C, Rodriguez E, Talabot‐Ayer D, Rose‐John S, Chalaris A, Gabay C. Mouse neutrophils express the decoy type 2 interleukin‐1 receptor (IL‐1R2) constitutively and in acute inflammatory conditions. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:791–802. DOI: 10.1189/jlb.0113035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elghetany MT, Patel J. Assessment of CD24 expression on bone marrow neutrophilic granulocytes: CD24 is a marker for the myelocytic stage of development. Am J Hematol. 2002;71:348–349. DOI: 10.1002/ajh.10176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kjeldsen L, Johnsen AH, Sengelov H, Borregaard N. Isolation and primary structure of ngal, a novel protein associated with human neutrophil gelatinase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10425–10432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang D, Chen G, Manwani D, Mortha A, Xu C, Faith JJ, Burk RD, Kunisaki Y, Jang J‐E, Scheiermann C, et al. Neutrophil ageing is regulated by the microbiome. Nature. 2015;525:528–532. DOI: 10.1038/nature15367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uhl B, Vadlau Y, Zuchtriegel G, Nekolla K, Sharaf K, Gaertner F, Massberg S, Krombach F, Reichel CA. Aged neutrophils contribute to the first line of defense in the acute inflammatory response. Blood. 2016;128:2327–2337. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-718999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adrover JM, Nicolas‐Avila JA, Hidalgo A. Aging: a temporal dimension for neutrophils. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:334–345. DOI: 10.1016/j.it.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhu YP, Padgett L, Dinh HQ, Marcovecchio P, Blatchley A, Wu R, Ehinger E, Kim C, Mikulski Z, Seumois G, et al. Identification of an early unipotent neutrophil progenitor with pro‐tumoral activity in mouse and human bone marrow. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2329–2341.e8. DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Evrard M, Kwok IWH, Chong SZ, Teng KWW, Becht E, Chen J, Sieow JL, Penny HL, Ching GC, Devi S, et al. Developmental analysis of bone marrow neutrophils reveals populations specialized in expansion, trafficking, and effector functions. Immunity. 2018;48:364–379.e8. DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yu C, Cantor AB, Yang H, Browne C, Wells RA, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH. Targeted deletion of a high‐affinity GATA‐binding site in the GATA‐1 promoter leads to selective loss of the eosinophil lineage in vivo. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1387–1395. DOI: 10.1084/jem.20020656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Han X, Wang R, Zhou Y, Fei L, Sun H, Lai S, Saadatpour A, Zhou Z, Chen H, Ye F, et al. Mapping the mouse cell atlas by microwell‐seq. Cell. 2018;173:1307. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fairfax KA, Bolden JE, Robinson AJ, Lucas EC, Baldwin TM, Ramsay KA, Cole R, Hilton DJ, de Graaf CA. Transcriptional profiling of eosinophil subsets in interleukin‐5 transgenic mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2018;104:195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Caceres RA, Timmers LF, Ducati RG, da Silva DO, Basso LA, de Azevedo WF Jr, Santos DS. Crystal structure and molecular dynamics studies of purine nucleoside phosphorylase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis associated with acyclovir. Biochimie. 2012;94:155–165. DOI: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martini E, Kunderfranco P, Peano C, Carullo P, Cremonesi M, Schorn T, Carriero R, Termanini A, Colombo FS, Jachetti E, et al. Single‐cell sequencing of mouse heart immune infiltrate in pressure overload‐driven heart failure reveals extent of immune activation. Circulation. 2019;140:2089–2107. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suetomi T, Willeford A, Brand CS, Cho Y, Ross RS, Miyamoto S, Brown JH. Inflammation and NLRP3 inflammasome activation initiated in response to pressure overload by Ca(2+)/calmodulin‐dependent protein kinase II delta signaling in cardiomyocytes are essential for adverse cardiac remodeling. Circulation. 2018;138:2530–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xia Y, Lee K, Li N, Corbett D, Mendoza L, Frangogiannis NG. Characterization of the inflammatory and fibrotic response in a mouse model of cardiac pressure overload. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;131:471–481. DOI: 10.1007/s00418-008-0541-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Song X, Kusakari Y, Xiao CY, Kinsella SD, Rosenberg MA, Scherrer‐Crosbie M, Hara K, Rosenzweig A, Matsui T. mTOR attenuates the inflammatory response in cardiomyocytes and prevents cardiac dysfunction in pathological hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299:C1256–C1266. DOI: 10.1152/ajpcell.00338.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Meyer N, Penn LZ. Reflecting on 25 years with MYC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:976–990. DOI: 10.1038/nrc2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Johansen LM, Iwama A, Lodie TA, Sasaki K, Felsher DW, Golub TR, Tenen DG. c‐Myc is a critical target for c/EBPalpha in granulopoiesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3789–3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Delgado MD, Leon J. Myc roles in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:605–616. DOI: 10.1177/1947601910377495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nie Z, Hu G, Wei G, Cui K, Yamane A, Resch W, Wang R, Green D, Tessarollo L, Casellas R, et al. c‐Myc is a universal amplifier of expressed genes in lymphocytes and embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2012;151:68–79. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maier C, Dickhaus H. Confounding factors in ECG‐based detection of sleep‐disordered breathing. Methods Inf Med. 2018;57:146–151. DOI: 10.3414/ME17-02-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wall M, Poortinga G, Hannan KM, Pearson RB, Hannan RD, McArthur GA. Translational control of c‐MYC by rapamycin promotes terminal myeloid differentiation. Blood. 2008;112:2305–2317. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-111856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdottir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P. The molecular signatures database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Xie X, Shi Q, Wu P, Zhang X, Kambara H, Su J, Yu H, Park S‐Y, Guo R, Ren Q, et al. Single‐cell transcriptome profiling reveals neutrophil heterogeneity in homeostasis and infection. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1119–1133. DOI: 10.1038/s41590-020-0736-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oeckinghaus A, Ghosh S. The NF‐kappaB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Beinke S, Ley SC. Functions of NF‐kappaB1 and NF‐kappaB2 in immune cell biology. Biochem J. 2004;382:393–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF‐kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mosser DM. The many faces of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:209–212. DOI: 10.1189/jlb.0602325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:787–795. 10.1172/JCI59643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Injarabian L, Devin A, Ransac S, Marteyn BS. Neutrophil metabolic shift during their lifecycle: impact on their survival and activation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;21:287. DOI: 10.3390/ijms21010287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Toor IS, Rückerl D, Mair I, Ainsworth R, Meloni M, Spiroski A‐M, Benezech C, Felton JM, Thomson A, Caporali A, et al. Eosinophil deficiency promotes aberrant repair and adverse remodeling following acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans Science. 2020;5:665–681. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Figures S1–S9