Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic disproportionately affects individuals with hypertension and health disparities.

Methods and Results

We assessed the experiences and beliefs of low‐income and minority patients with hypertension during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Participants (N=587) from the IMPACTS‐BP (Implementation of Multifaceted Patient‐Centered Treatment Strategies for Intensive Blood Pressure Control) study completed a telephone survey in May and June of 2020. Participants were 65.1% Black and 59.7% female, and 57.7% reported an income below the federal poverty level. Overall, 2.7% tested positive and 15.3% had lost a family member or friend to COVID‐19. These experiences were significantly more common in Black (3.9% and 19.4%, respectively) than in non‐Black participants (0.5% and 7.8%, respectively). In addition, 14.5% lost a job and 15.9% reported food shortages during the pandemic. Most participants complied with stay‐at‐home orders (98.3%), social distancing (97.8%), and always wearing a mask outside their home (74.6%). Participants also reported high access to needed health care (94.7%) and prescription medications (97.6%). Furthermore, 95.7% of respondents reported that they continued to take their regular dosage of antihypertensive medications. Among the 44.5% of participants receiving a healthcare appointment by telehealth, 96.6% got the help they needed, and 80.8% reported that the appointment quality was as good as or better than in‐person visits. Finally, 88.9% were willing to return to their primary care clinic.

Conclusions

These data suggest that low‐income patients, especially Black patients, were negatively impacted by COVID‐19. However, most patients were able to access needed healthcare services and were willing to return to their primary care clinic for hypertension management.

Registration

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT03483662.

Keywords: access to care, COVID‐19, health disparities, hypertension, telemedicine

Subject Categories: Epidemiology, Race and Ethnicity, High Blood Pressure, Hypertension

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- FQHC

federally qualified health center

- IMPACTS‐BP

Implementation of Multifaceted Patient‐Centered Treatment Strategies for Intensive Blood Pressure Control

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Low‐income and racial and ethnic minority patients with hypertension from federally qualified health centers have been negatively impacted by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), including loss of life, income, and food security.

Participants reported high compliance with stay‐at‐home orders, social distancing, and mask wearing, continued access to health care and prescription medications, and positive experiences with telehealth; and almost 90% of patients were willing to return to their primary care clinic for in‐person visits.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, federally qualified health center patients with hypertension have been able to access needed health services and medications, including through telehealth appointments, and are willing to return to their primary care clinics for hypertension management.

The pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) has led to widespread stay‐at‐home orders throughout the United States and disruption of daily life, including access to healthcare facilities for chronic disease care. Low‐income and racial and ethnic minority populations have experienced disproportionately greater rates of infection, hospitalization, and death associated with COVID‐19 compared with their higher income and White counterparts. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4

Hypertension is the most common comorbidity among people who are hospitalized for COVID‐19 and those with subsequent mortality. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Evidence also suggests that people with treated hypertension have better survival after COVID‐19 hospitalization than those with untreated hypertension. 8 As such, continued management of elevated blood pressure (BP) is critically important, even while healthcare resources are shifted toward care for COVID‐19. Telehealth has been expanded rapidly and used widely used for acute and chronic care management during the COVID‐19 outbreak. 9 , 10 Better understanding of patient perceptions of healthcare access for chronic care management during the COVID‐19 outbreak, especially among minority and low‐income populations, is needed to improve healthcare delivery moving forward.

The IMPACTS‐BP (Implementation of Multifaceted Patient‐Centered Treatment Strategies for Intensive Blood Pressure Control) study is a cluster‐randomized trial testing implementation of an intensive BP treatment intervention conducted in 36 federally qualified health center (FQHC) clinics in Louisiana and Mississippi. IMPACTS‐BP provides a unique opportunity to better understand the effects of COVID‐19 on low‐income and Black patients with hypertension. We conducted a phone survey of IMPACTS‐BP study participants with the objective of understanding their experiences, perceptions, and beliefs, including access to health care for chronic disease management during the COVID‐19 pandemic and as stay‐at‐home orders are lifting.

Methods

Study Setting and Population

IMPACTS‐BP is being conducted in 36 primary care clinics, which are part of 8 FQHCs in south Louisiana and Mississippi. FQHCs receive federal funding under Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act to provide health care for underserved geographic areas, and, as such, predominantly provide health care for minority and low‐income populations. 11

IMPACTS‐BP recruits participants who are at least 40 years of age, have a baseline systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg if not taking antihypertensive medications or ≥130 mm Hg if taking antihypertensive medications, and receive their primary care at one of the participating clinics. Participants must be able to understand English and plan to continue receiving their health care at the same primary care clinic for the 18‐month duration of the trial. IMPACTS‐BP has been approved by the Tulane University Institutional Review Board and is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03483662), and all study participants gave informed consent.

Louisiana was under a stay‐at‐home from March 22 to May 14, and Mississippi was under a stay‐at‐home order from April 1 to April 27, 12 after which, some restrictions lifted, but citizens were advised to stay home and take precautions against COVID‐19. For the present analysis, trained clinical research coordinators called all 849 active IMPACTS‐BP study participants between May 11 and June 12, 2020, to invite them to participate in a brief telephone survey regarding their experiences and perceptions during the COVID‐19 pandemic. A total of 587 completed the telephone survey (69.1% response rate). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Data Collection

COVID‐19 survey items were based on questionnaires used previously for assessing social determinants of health‐ and disaster‐related needs and experiences, including with COVID‐19 (survey available in Data S1). 13 , 14 , 15 Questions were asked about participants’ experiences during the COVID‐19 outbreak, including testing positive, exposure to someone with COVID‐19, death of a family member or friend due to COVID‐19, loss of job or being required to work a job at high risk for COVID‐19 exposure, food shortages during the outbreak, and loneliness related to staying at home. Participants were asked about their use of protective measures, including staying at home, use of face masks, and social distancing. Participants were also asked about their concerns about being infected by COVID‐19 in different locations after stay‐at‐home orders are lifted. They were further asked about access to medical care and prescription medications during stay‐at‐home orders, including use of telehealth services.

IMPACTS‐BP data are collected at baseline and every 6 months. Participant characteristics for this analysis were captured from the most recent data collection visit prior to survey administration when each item was assessed. These data include self‐reported sociodemographic characteristics (age, race, ethnicity, marital status, income, education, employment, and insurance coverage), medical history, and health behaviors (eg, smoking and alcohol drinking). Age at survey administration was used, and all other sociodemographic characteristics were collected at IMPACTS‐BP study baseline up to 18 months before survey administration. Most recent medical history and health behaviors collected up to 6 months before the survey were used in this analysis. In addition, three BP measurements were collected at each of two baseline visits according to a standard protocol recommended by the American Heart Association, 16 and the average of the six measurements was used to calculate baseline BP. Height and weight were also measured at the most recent data collection visit using a standard protocol and used to calculate body mass index (BMI).

Statistical Analysis

Percentages were calculated for all categorical variables, and means and standard deviations were estimated for all continuous variables. The association between patient characteristics and experiences with COVID‐19 were evaluated in bivariate analyses using χ 2 tests or Fisher exact tests (used when 20% or more expected cell frequencies were <5). For variables with significant race and sex differences, percentages were calculated within each race/sex category to examine combined effects. Comparisons of key characteristics between survey respondents and nonrespondents were conducted using χ 2 tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Demographic information, socioeconomic factors, and medical history of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. The majority of participants were female (59.7%) and Black (65.1%). In addition, 57.7% were living below the federal poverty level, 58.2% had high school or lower education, 61.6% were retired or unemployed, 81.1% had Medicare/Medicaid insurance, and 14.8% were uninsured. Comorbidities were common, including diabetes mellitus in 39.5%, diagnosed depression in 32.5%, and history of a major cardiovascular disease event in 19.4%. In addition, respondents reported their general health to be good to excellent (56.9%), fair (32.4%), or poor (10.7%). Respondents and nonrespondents did not differ in key sociodemographic and clinical indicators, such as age, race, sex, and medical history (Table S1). The only significant difference was lower attained education level among nonrespondents compared with respondents.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of 587 Patients With Hypertension From 36 FQHC Clinics in Louisiana and Mississippi

| Characteristic | N (%) or Mean±SD |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, y | 59.4±9.0 |

| Female | 350 (59.7) |

| Race | |

| Black or African American | 381 (65.1) |

| White or Caucasian | 180 (30.8) |

| Other† | 24 (4.1) |

| Hispanic | 23 (3.9) |

| Married | 182 (31.2) |

| Socioeconomics | |

| Below federal poverty level | 331 (57.7) |

| Education level | |

| Less than high school | 134 (22.9) |

| High school graduate | 207 (35.3) |

| Some education after high school | 245 (41.8) |

| Employment | |

| Working full or part time | 215 (38.3) |

| Retired | 210 (37.4) |

| Unemployed | 136 (24.2) |

| Insurance coverage* | |

| Medicare | 170 (29.0) |

| Medicaid | 306 (52.1) |

| Private/other | 112 (19.1) |

| Uninsured | 87 (14.8) |

| Medical history | |

| Current smoker | 147 (25.2) |

| Current alcohol drinker | 239 (41.0) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 33.9±7.8 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 139.8±18.4 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 84.5±18.2 |

| History of hypertension at enrollment | 563 (97.6) |

| Use of antihypertensive medications at enrollment | 543 (96.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 228 (39.5) |

| Use of anti‐diabetes mellitus medications | 188 (33.0) |

| High cholesterol | 369 (64.0) |

| Depression | 187 (32.5) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 112 (19.4) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 21 (3.6) |

| Self‐Reported general health | |

| Excellent | 24 (4.1) |

| Very good | 87 (15.0) |

| Good | 219 (37.8) |

| Fair | 188 (32.4) |

| Poor | 62 (10.7) |

FQHC, federally qualified health center; and SD, standard deviation.

Some participants are covered by more than one type of insurance.

Other racial groups include Asian or Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Other.

Experiences With COVID‐19

Overall, 2.7% of the study participants reported testing positive for COVID‐19, with Black participants reporting a higher positive test rate than non‐Black participants (3.9% versus 0.5%; P=0.01) (Table 2). In addition, 7.3%, 25.1%, and 15.3% of participants reported having been exposed to someone with confirmed COVID‐19, having a family member or friend with COVID‐19, and death of a family member or friend due to COVID‐19, respectively. These experiences were all significantly more common in Black versus non‐Black participants (P=0.003, P=0.001, and P=0.0002, respectively). Furthermore, when looking at the combined effect of race and sex, Black women were most likely to have experienced the death of a loved one (23.4%) compared with Black men (13.3%), non‐Black women (9.2%), and non‐Black men (5.8%). Those who were employed were more likely to report having been exposed to someone with confirmed COVID‐19 and having a family member or friend who died due to COVID‐19 compared with those who were retired or unemployed (P=0.009 and P=0.04, respectively). Overall, 14.5% of participants reported having lost their job during the COVID‐19 pandemic, 14.5% having been required to work in a job that put them at increased risk of infection, and 2.9% having lost their health insurance coverage. In addition, 15.9% of respondents reported experiencing food shortages, with participants <65 years of age experiencing greater food insecurity compared with those 65 years and older (P<0.0001). Over one fourth of participants (26.5%) reported experiencing loneliness because of remaining at home.

Table 2.

COVID‐19 Experiences Among 587 Patients With Hypertension From 36 FQHC Clinics in Louisiana and Mississippi

| Characteristic | Tested Positive For COVID‐19, N (%) | Exposure to Someone With Confirmed COVID‐19, N (%) | Family or Friend With COVID‐19, N (%) | Loss of Family or Friend Due to COVID‐19, N (%) | Laid Off or Furloughed Due to COVID‐19, N (%) | Required to Working at High Risk Job For COVID‐19 infection, N (%) | Loss of Health Insurance During COVID‐19, N (%) | Shortages of Food During COVID‐19, N (%) | Loneliness Due to Quarantine, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 16 (2.7) | 43 (7.3) | 147 (25.1) | 90 (15.3) | 85 (14.5) | 85 (14.5) | 17 (2.9) | 93 (15.9) | 154 (26.5) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 12 (3.4) | 31 (8.9) | 89 (25.5) | 65 (18.6) † | 54 (15.4) | 46 (13.1) | 9 (2.6) | 63 (18.0) | 102 (29.5) |

| Male | 4 (1.7) | 12 (5.1) | 57 (24.2) | 25 (10.6) † | 31 (13.1) | 39 (16.5) | 8 (3.4) | 29 (12.3) | 52 (22.2) |

| Race | |||||||||

| Black | 15 (3.9)* | 37 (9.7) † | 111 (29.2) † | 74 (19.4) † | 61 (16.0) | 59 (15.5) | 11 (2.9) | 65 (17.1) | 98 (26.1) |

| Non‐Black | 1 (0.5)* | 6 (2.9) † | 36 (17.5) † | 16 (7.8) † | 24 (11.7) | 26 (12.6) | 6 (2.9) | 28 (13.6) | 56 (27.2) |

| Age | |||||||||

| ≥65 y | 3 (1.9) | 9 (5.8) | 32 (20.6) | 24 (15.5) | 10 (6.5) † | 9 (5.8) † | 2 (1.3) | 9 (5.8) ‡ | 36 (23.5) |

| <65 y | 13 (3.0) | 34 (7.9) | 115 (26.7) | 66 (15.3) | 75 (17.4) † | 76 (17.6) † | 15 (3.5) | 84 (19.5) ‡ | 118 (27.6) |

| High school education or higher | |||||||||

| Yes | 12 (2.7) | 36 (8.0) | 122 (27.1)* | 79 (17.5) † | 72 (15.9) | 76 (16.8) † | 15 (3.3) | 73 (16.2) | 115 (25.7) |

| No | 4 (3.0) | 7 (5.2) | 25 (18.7)* | 11 (8.2) † | 13 (9.7) | 9 (6.7) † | 2 (1.5) | 20 (14.9) | 38 (28.8) |

| Type of insurance | |||||||||

| Public | 13 (3.1) | 28 (6.6) | 108 (25.6) | 66 (15.6) | 55 (13.0) | 42 (10.0) ‡ | 10 (2.4) | 70 (16.6) | 124 (29.6)* |

| Private | 1 (1.3) | 10 (12.8) | 19 (24.7) | 9 (11.5) | 12 (15.4) | 26 (33.3) ‡ | 3 (3.8) | 6 (7.7) | 14 (18.4)* |

| Uninsured | 2 (2.3) | 5 (5.8) | 20 (23.3) | 15 (17.4) | 18 (20.9) | 17 (19.8) ‡ | 4 (4.7) | 17 (19.8) | 16 (18.8)* |

| Employment | |||||||||

| Employed | 7 (3.2) | 25 (11.6) † | 63 (29.3) | 41 (19.0)* | 67 (31.0) ‡ | 78 (36.1) ‡ | 13 (6.0) † | 39 (18.1) | 53 (24.7) |

| Retired | 5 (2.4) | 11 (5.2) † | 51 (24.2) | 31 (14.7)* | 7 (3.3) ‡ | 0 (0.0) ‡ | 2 (0.9) † | 24 (11.4) | 62 (29.8) |

| Unemployed | 4 (2.7) | 6 (4.1) † | 28 (18.9) | 14 (9.5)* | 10 (6.8) ‡ | 7 (4.7) ‡ | 2 (1.4) † | 28 (19.0) | 36 (24.7) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | |||||||||

| <25 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.4) | 16 (27.6) | 11 (19.0) | 8 (13.8) | 10 (17.2) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (19.0) | 17 (29.8) |

| 25‐29.9 | 3 (2.3) | 7 (5.3) | 32 (24.4) | 22 (16.8) | 16 (12.2) | 17 (13.0) | 6 (4.6) | 18 (13.7) | 36 (28.1) |

| ≥30 | 13 (3.4) | 33 (8.6) | 97 (25.3) | 55 (14.3) | 59 (15.3) | 57 (14.8) | 11 (2.9) | 63 (16.4) | 99 (25.8) |

| Number of comorbidities § | |||||||||

| 0 | 5 (3.7) | 13 (9.6) | 32 (23.7) | 20 (14.7) | 27 (19.9) | 30 (22.1) † | 10 (7.4) † | 22 (16.2) | 34 (25.0) |

| 1 | 3 (1.4) | 10 (4.7) | 47 (22.3) | 26 (12.3) | 24 (11.4) | 29 (13.7) † | 3 (1.4) † | 32 (15.2) | 54 (26.1) |

| 2+ | 8 (3.5) | 19 (8.3) | 62 (27.1) | 39 (17.0) | 30 (13.1) | 22 (9.6) † | 4 (1.7) † | 36 (15.7) | 61 (26.9) |

COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; and FQHC, federally qualified health center.

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.0001.

Comorbidities include diabetes mellitus, high cholesterol, history of stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease in addition to hypertension.

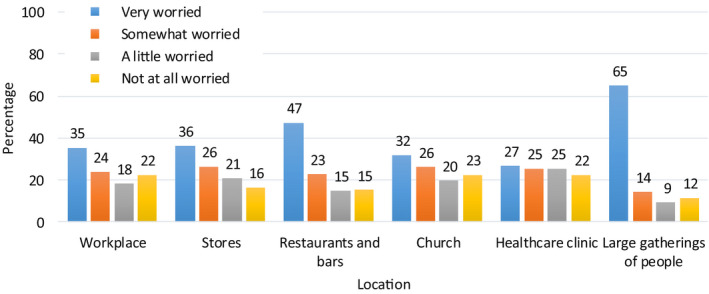

Following the lifting of stay‐at‐home orders, participants were most worried about getting COVID‐19 infection in the context of large gatherings (64.9% very worried) (Figure 1). In addition, 47.3%, 36.3%, 35.4%, and 31.9% were very worried about returning to restaurants and bars, stores, workplaces, and churches, respectively. Participants were least concerned about returning to their healthcare clinics, with only 26.7% very worried and 22.5% not worried at all. Black participants were significantly more worried about returning to each location than non‐black participants, except for healthcare clinics, for which there was no racial difference (Figure S1).

Figure 1. Participant concern about contracting the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) by location as stay‐at‐home orders are lifted.

Protective Practices

A majority of the participants reported staying home as much as possible (98.3%) and keeping at least 6 feet from other people when outside their home (97.8%) to protect themselves from COVID‐19 (Table 3). In addition, 74.6% of participants reported always wearing a mask outside their home, with a higher percentage among women and Black participants. Black women were most likely to wear a mask (85.7%) compared with Black men (74.5%), non‐Black women (70.6%), and non‐Black men (50.0%). Among those who reported not always wearing a mask, the most common reason was that they never left their home (32.4%), followed by the belief that masks did not protect against COVID‐19 (28.9%), an inability to buy them (21.6%), and the belief that the government should not tell people to wear them (19.6%).

Table 3.

Use of COVID‐19 Protections Among 587 Patients With Hypertension From 36 FQHC Clinics in Louisiana and Mississippi

| Characteristic | Types of Protective Practices (N=587) | Reasons for Not Always Wearing a Mask Among Those Who Do Not (N=149) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stay Home as Much as Possible N (%) | Social Distance at Least 6 Feet, N (%) | Always Wear of Mask Outside the House, N (%) | Belief Only Sick People Need Them, N (%) | Belief Masks Not Protective, N (%) | Not Able or Cannot Afford to Buy Them, N (%) | Belief That Government Should Not Tell People to Wear One, N (%) | Do Not Leave the House, N (%) | |

| Overall | 577 (98.3) | 570 (97.8) | 437 (74.6) | 23 (15.4) | 43 (28.9) | 32 (21.6) | 29 (19.6) | 48 (32.4) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 346 (98.9) | 343 (98.8)* | 282 (80.6) ‡ | 7 (10.3) | 16 (23.5) | 18 (26.9) | 12 (17.6) | 28 (41.8)* |

| Male | 230 (97.5) | 226 (96.2)* | 154 (65.5) ‡ | 16 (19.8) | 27 (33.3) | 14 (17.3) | 17 (21.3) | 20 (24.7)* |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black | 376 (98.7) | 371 (97.9) | 309 (81.3) ‡ | 7 (9.9) | 14 (19.7)* | 18 (25.4) | 10 (14.1) | 19 (26.8) |

| Non‐Black | 201 (97.6) | 199 (97.5) | 128 (62.1) ‡ | 16 (20.5) | 29 (37.2)* | 14 (18.2) | 19 (24.7) | 29 (37.7) |

| Age | ||||||||

| ≥65 y | 154 (99.4) | 151 (98.7) | 121 (78.1) | 2 (5.9) | 7 (20.6) | 6 (17.6) | 5 (15.2) | 12 (35.3) |

| <65 y | 423 (97.9) | 419 (97.4) | 316 (73.3) | 21 (18.3) | 36 (31.3) | 26 (22.8) | 24 (20.9) | 36 (31.6) |

| High school education or higher | ||||||||

| Yes | 442 (97.8) | 438 (97.8) | 339 (75.0) | 17 (15.0) | 33 (29.2) | 22 (19.6) | 21 (18.6) | 36 (32.1) |

| No | 134 (100.0) | 131 (97.8) | 97 (72.9) | 6 (16.7) | 10 (27.8) | 10 (27.8) | 8 (22.9) | 12 (33.3) |

| Type of insurance | ||||||||

| Public | 416 (98.6) | 409 (97.8) | 322 (76.3) | 8 (8.0) ‡ | 26 (26.0) | 24 (24.0) | 19 (19.2) | 32 (32.0) |

| Private | 75 (96.2) | 75 (96.2) | 59 (75.6) | 9 (47.4) ‡ | 8 (42.1) | 3 (16.7) | 4 (21.1) | 5 (27.8) |

| Uninsured | 85 (98.8) | 85 (98.8) | 56 (65.9) | 5 (17.2) ‡ | 8 (27.6) | 4 (17.2) | 6 (20.7) | 10 (34.5) |

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed | 209 (96.8) | 209 (97.2) | 158 (73.1) | 11 (19.0) | 18 (31.0) | 10 (17.5) | 15 (25.9) | 12 (21.1)* |

| Retired | 210 (99.5) | 207 (98.6) | 160 (75.8) | 8 (15.7) | 11 (21.6) | 14 (27.5) | 6 (12.0) | 22 (43.1)* |

| Unemployed | 146 (98.6) | 142 (97.3) | 110 (74.8) | 3 (8.1) | 11 (29.7) | 8 (21.6) | 7 (18.9) | 12 (32.4)* |

| Body mass index | ||||||||

| Normal | 56 (96.6) | 56 (96.6) | 41 (71.9) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (18.7) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (6.2) | 5 (31.2) |

| Overweight | 127 (96.9) | 128 (97.7) | 98 (74.8) | 7 (21.2) | 9 (27.3) | 7 (21.9) | 8 (24.2) | 9 (28.1) |

| Obese | 381 (99.0) | 375 (98.2) | 288 (74.8) | 15 (15.5) | 31 (32.0) | 22 (22.7) | 20 (20.8) | 31 (32.0) |

| Number of comorbidities § | ||||||||

| 0 | 132 (97.1) | 131 (96.3) | 102 (75.0) | 4 (11.8)* | 12 (35.3) | 4 (12.1) | 10 (29.4) | 9 (27.3) |

| 1 | 207 (98.1) | 207 (98.6) | 154 (73.0) | 15 (26.3)* | 19 (33.3) | 15 (26.3) | 13 (22.8) | 18 (31.6) |

| 2+ | 227 (99.1) | 221 (97.8) | 172 (75.4) | 4 (7.1)* | 12 (21.4) | 13 (23.2) | 6 (10.9) | 21 (37.5) |

COVID‐19 indicates coronavirus disease 2019; and FQHC, federally qualified health center.

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.0001.

Comorbidities include diabetes mellitus, high cholesterol, history of stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease in addition to hypertension.

Access to Health Care

Among those reporting needing medical care during the outbreak, 94.7% report being able to get the care they needed. Overall, 97.6% reported being able to get prescription medications (Table 4). Accessed care included in‐person clinic visits (reported by 32.9% of respondents) and telehealth visits (reported by 44.5% of respondents). Nearly all participants with telehealth visits (96.6%) reported getting the treatment they needed, and 80.8% reported that the quality of care of telehealth visits was the same or better compared with in‐person visits. Among those receiving telehealth appointments, 61.3% of appointments were conducted by phone only, 18.4% were conducted by video only, and 20.3% were conducted by phone and video.

Table 4.

Access to Health Care Among 587 Patients With Hypertension from 36 FQHC Clinics in Louisiana and Mississippi

| Characteristic | Taken Less or No Antihypertensive Medications, N (%) | Access to Care during COVID‐19 Pandemic | Telehealth Experiences (N=261) | Willing to Return to Primary Care Clinic, N (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Able to Get Needed Medical Care, N (%) | Able to Get Prescription Medications, N (%) | Attended in‐Person Clinic Visits, N (%) | Received Telehealth Visits, N (%) | Received Needed Treatment, N (%) | Same or Better Care Quality Compared to In‐Person Visits, N (%) | |||

| Overall | 25 (4.3) | 160 (94.7) | 572 (97.6) | 193 (32.9) | 261 (44.5) | 252 (96.6) | 210 (80.8) | 522 (88.9) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 19 (5.4) | 100 (93.5) | 339 (97.1) | 118 (33.7) | 149 (42.7) | 143 (96.0) | 120 (81.1) | 308 (88.0) |

| Male | 6 (2.5) | 59 (96.7) | 232 (98.3) | 75 (31.8) | 111 (47.0) | 108 (97.3) | 89 (80.2) | 213 (90.3) |

| Race | ||||||||

| Black | 15 (3.9) | 100 (95.2) | 370 (97.4) | 130 (34.1) | 166 (43.7) | 161 (97.0) | 134 (81.2) | 335 (87.9) |

| Non‐Black | 10 (4.9) | 60 (93.7) | 202 (98.1) | 63 (30.6) | 95 (46.1) | 91 (95.8) | 76 (80.0) | 187 (90.8) |

| Age | ||||||||

| ≥65 y | 2 (1.3)* | 39 (95.1) | 154 (99.4) | 52 (33.5) | 59 (38.3) | 57 (96.6) | 45 (77.6) | 130 (83.9)* |

| <65 y | 23 (5.3)* | 121 (94.5) | 418 (97.0) | 141 (32.6) | 202 (46.8) | 195 (96.5) | 165 (81.7) | 392 (90.7)* |

| High school education or higher | ||||||||

| Yes | 19 (4.2) | 122 (93.1) | 442 (97.8) | 146 (32.3) | 203 (45.0) | 197 (97.0) | 164 (81.2) | 403 (89.2) |

| No | 6 (4.5) | 38 (100.0) | 129 (97.0) | 47 (35.1) | 58 (43.3) | 55 (94.8) | 46 (79.3) | 118 (88.1) |

| Type of insurance | ||||||||

| Public | 21 (5.0) | 117 (95.1) | 410 (97.4) | 144 (34.1) | 194 (46.1) | 187 (96.4) | 152 (78.8) | 366 (86.7)* |

| Private | 1 (1.3) | 24 (92.3) | 77 (98.7) | 25 (32.1) | 30 (38.5) | 29 (96.7) | 26 (86.7) | 74 (94.9)* |

| Uninsured | 3 (3.5) | 19 (95.0) | 84 (97.7) | 24 (27.9) | 37 (43.0) | 36 (97.3) | 32 (86.5) | 81 (94.2)* |

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed | 12 (5.6) | 58 (92.1) | 211 (97.7) | 68 (31.5) | 99 (45.8) | 94 (94.9) | 80 (80.8) | 198 (91.7) |

| Retired | 9 (4.3) | 54 (96.4) | 206 (97.6) | 64 (30.3) | 87 (41.4) | 84 (96.6) | 69 (80.2) | 179 (84.8) |

| Unemployed | 4 (2.7) | 43 (95.6) | 145 (98.0) | 56 (37.8) | 69 (46.6) | 68 (98.6) | 56 (81.2) | 134 (90.5) |

| Body mass index | ||||||||

| Normal | 2 (3.4) | 12 (92.3) | 54 (93.1) | 17 (29.3) | 27 (46.6) | 24 (88.9) † | 25 (92.6) | 51 (87.9) |

| Overweight | 2 (1.5) | 37 (90.2) | 129 (98.5) | 42 (32.1) | 54 (41.2) | 50 (92.6) † | 42 (77.8) | 110 (84.0) |

| Obese | 20 (5.2) | 105 (96.3) | 376 (97.9) | 132 (34.3) | 176 (45.8) | 174 (98.9) † | 141 (80.1) | 350 (90.9) |

| Number of comorbidities § | ||||||||

| 0 | 7 (5.1) | 26 (86.7)* | 131 (96.3) | 42 (30.9) | 59 (43.4) | 54 (91.5) † | 47 (79.7) | 126 (92.6) |

| 1 | 11 (5.2) | 60 (93.7)* | 204 (96.7) | 60 (28.4) | 93 (44.3) | 89 (95.7) † | 78 (83.9) | 191 (90.5) |

| 2+ | 7 (3.1) | 71 (98.6)* | 226 (99.1) | 88 (38.4) | 99 (43.2) | 99 (100.0) † | 77 (78.6) | 197 (86.0) |

COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; and FQHC, federally qualified health center.

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.0001.

Comorbidities include diabetes mellitus, high cholesterol, history of stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease in addition to hypertension.

Overall, 88.9% of the participants reported being willing to return to their primary care clinics to receive care (Table 4), with 62.0% being very willing, 26.9% being somewhat willing, and only 6.8% and 4.3% not that willing or not at all willing, respectively. Participants 65 years of age or older were significantly less willing to return compared with younger participants. Of those who were not very willing to return to the clinic, 91.9% reported concerns about being exposed to COVID‐19 at the clinic, 33.5% concerns about COVID‐19 exposure when using public transportation, 28.1% difficulty making an appointment due to limited availability, and 13.2% lack of transportation.

Only 4.3% of participants reported taking less or not taking BP medications since the COVID‐19 pandemic began (Table 4). Among the participants who had stopped or reduced their medications (N=25), 45.8% reported that it was due to lack of access to a provider to obtain a medication refill, 16.7% reported it was due to lack of transportation, 12.5% said they could not afford the medications, and 8.3% were concerned that taking certain medications could make COVID‐19 symptoms worse. In addition, 66.3% of participants reported having heard that uncontrolled BP makes COVID‐19 symptoms worse in those who were infected.

Discussion

Our survey, conducted in 587 patients with hypertension at FQHC clinics in underserved areas of Louisiana and Mississippi, has several important findings. Participants reported negative personal and financial impacts of COVID‐19 through COVID‐19 diagnoses, death of family members and friends, job losses, and food insecurity. Furthermore, participants reported high adherence to taking recommended steps to protect themselves from COVID‐19 transmission, including remaining at home, social distancing outside their home, and wearing a mask. Participants also reported adequate access to health care, positive experiences with telehealth, and a willingness to return to their primary care clinics. Findings from this survey can be used to better understand the needs and experiences of minority and low‐income patient populations with chronic disease during the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic.

The toll of COVID‐19 on the IMPACTS‐BP patient population has been substantial, with 25.1% and 15.3% reporting a COVID‐19 diagnosis and COVID‐19‐related death of a family member or friend, respectively. Black participants disproportionately reported a COVID‐19 diagnosis, exposure to COVID‐19, and death of a family member or friend due to COVID‐19 compared with non‐Black participants. These findings are consistent with previous reports that Black communities have been more affected by COVID‐19 in terms of diagnosis, hospitalization, and death. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 These health disparities are not completely understood but may be due to a higher prevalence of comorbidities, uncontrolled chronic conditions, and social determinants of health, such as greater housing density and economic disadvantage. 1 , 17 , 18 There is a pressing need to better understand the factors related to these disparities so that interventions can be developed to reduce the impact of COVID‐19 on the Black community.

Overall, survey respondents reported very high use of proven effective and recommended protective practices for COVID‐19 transmission, including staying at home as much as possible (98.3%), social distancing by at least 6 feet (97.8%), and always wearing face masks (74.6%). 19 Among those participants who did not report always wearing a face mask, three common reasons for not wearing them were the beliefs that masks do not protect against COVID‐19, only sick people need to wear them, and the government should not tell people to wear one. These responses indicate that there is a need for clearer messaging around the importance and effectiveness of masks for prevention of COVID‐19. Furthermore, men and non‐Black participants were less likely to report always wearing a mask, so targeted educational interventions in these groups could be useful for increasing mask use overall.

Survey participants reported high access to health care (94.7%) and ability to obtain prescription medications (97.6%) during the COVID‐19 pandemic. A substantial proportion of patients (32.9%) continued to receive in‐person care, whereas 44.5% received care by telehealth visits, suggesting that strategies implemented by IMPACTS‐BP partner FQHCs during the COVID‐19 pandemic were effective at promoting continuity of care. This is particularly important for primary care patients with treated high BP because hypertension is the leading comorbidity for COVID‐19. 5 , 20 A recent report from China found that the risk of mortality from COVID‐19 was more than double in patients with untreated compared with those with treated hypertension. 8 This finding highlights the importance of continued treatment with antihypertensive medications during the COVID‐19 outbreak.

In response to stay‐at‐home orders and social distancing recommendations, there has been a rapid expansion of telehealth in the United States aided by Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services changes to reimbursement policies. 9 , 10 , 21 Our survey shows that among those who had a telehealth appointment, 96.6% reported getting the needed treatment and 80.8% reported that the quality of the care received by telehealth was the same or better than that from in‐person visits. These results show that despite the rapid transition to telehealth, it appears to be an effective method for delivering primary care in FQHCs during the pandemic. Prior studies have indicated that telehealth delivered by video is associated with higher patient satisfaction and understanding compared with delivery by phone alone. 22 , 23 Our participants reported that 61.3% of telehealth visits were conducted by phone only, so transitioning to video telehealth appointments in the future by potentially overcoming technological challenges could lead to even greater patient satisfaction with telehealth appointments.

Our study has several strengths, including a relatively large sample of low‐income patients with hypertension who receive primary care at FQHC clinics in Louisiana and Mississippi. Our findings may be generalizable to low‐income and minority primary care patients with chronic conditions. In addition, sociodemographic information, medical history, and clinical measurements were collected at IMPACTS‐BP study examinations by trained staff using established protocols. Finally, given that states are making decisions about reopening their economies, our survey findings are timely and can inform these decisions. Our study also has limitations. For example, survey data were self‐reported, and a moderate 69% of participants responded to the COVID‐19 survey. In addition, we did not inquire about how many participants were tested or the type of testing (ie, PCR, antigen, antibody/serology). Furthermore, IMPACTS‐BP does not include all patients with hypertension, as those with isolated diastolic hypertension and those with BP controlled below 130 mm Hg are not included. As such, caution must be exercised when interpreting these findings.

In conclusion, our survey among 587 predominantly low‐income and minority patients with hypertension in Louisiana and Mississippi found that the COVID‐19 pandemic had negative personal, professional, and economic impacts on these patients. In addition, these patients reported high rates of protective practices to prevent the spread of COVID‐19 and of access to quality health care during the outbreak either in person or by telehealth. In addition, patients are willing to return to their clinics for health care. These findings can inform policy related to re‐opening clinics and other public locations and for responding to COVID‐19 moving forward.

Sources of Funding

The Implementation of Multifaceted Patient‐Centered Treatment Strategies for Intensive Blood Pressure Control (IMPACTS‐BP) study is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health (R01HL133790). The authors’ work is also supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (P20GM109036).

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Data S1

Table S1

Figure S1

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all IMPACTS‐BP study participants, FQHC clinic administrators, staff, and providers, and study staff for contributing to the study.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e018510. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018510.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 9.

References

- 1. Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez‐Stable EJ. COVID‐19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323:2466–2467. 10.1001/jama.2020.8598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Azar KMJ, Shen Z, Romanelli RJ, Lockhart SH, Smits K, Robinson S, Brown S, Pressman AR. Disparities in outcomes among COVID‐19 patients in a large health care system In California. Health Aff. 2020;39:1253–1262. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Price‐Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and mortality among black patients and white patients with COVID‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2534–2543. 10.1056/NEJMsa2011686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Razavi AC, Kelly TN, He J, Fernandez C, Whelton PK, Krousel‐Wood M, Bazzano LA. Cardiovascular disease prevention and implications of COVID‐19: an Evolving Case Study in THE Crescent City. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e016997. 10.1161/JAHA.120.016997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, Barnaby DP, Becker LB, Chelico JD, Cohen SL, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID‐19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–2059. 10.1001/jama.2020.6775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li X, Xu S, Yu M, Wang KE, Tao YU, Zhou Y, Shi J, Zhou M, Wu BO, Yang Z, et al. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID‐19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:110–118. 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gao C, Cai Y, Zhang K, Zhou L, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Li QI, Li W, Yang S, Zhao X, et al. Association of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment with COVID‐19 mortality: a retrospective observational study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2058–2066. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mehrotra A, Ray K, Brockmeyer DM, Barnett ML, Bender JA. Rapidly converting to “virtual practices”: outpatient care in the era of Covid‐19. NEJM Catal. 2020;1:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nouri S, Khoong E, Lyles C, Karliner L. Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the Covid‐19 pandemic. NEJM Catal. 2020;3:e20049. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Health Resources & Services Administration . What is a Health Center? Bureau of Primary Health Care. Available at: https://bphc.hrsa.gov/about/what‐is‐a‐health‐center/index.html. Accessed July 7, 2020.

- 12. Moreland A, Herlihy C, Tynan MA, Sunshine G, McCord RF, Hilton C, Poovey J, Werner AK, Jones CD, Fulmer EB, et al. Timing of state and territorial covid‐19 stay‐at‐home orders and changes in population movement — United States, March 1–May 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1198–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wolf MS, Serper M, Opsasnick L, O’Conor RM, Curtis LM, Benavente JY, Wismer G, Batio S, Eifler M, Zheng P, et al. Awareness, attitudes, and actions related to COVID‐19 among adults with chronic conditions at the onset of the U.S. Outbreak. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:100–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Community Assessment for Public Health Emergency Response (CASPER) Toolkit, 3rd edition. Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laforge K, Gold R, Cottrell E, Bunce AE, Proser M, Hollombe C, Dambrun K, Cohen DJ, Clark KD. How 6 organizations developed tools and processes for social determinants of health screening in primary care: an overview. J Ambul Care Manage. 2018;41:2–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, Charleston JB, Gaillard T, Misra S, Myers MG, Ogedegbe G, Schwartz JE, Townsend RR, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertens. 2019;73:e35–e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, Blair IV, Cohen MS, Cruz‐Flores S, Davey‐Smith G, Dennison‐Himmelfarb CR, Lauer MS, Lockwood DW, et al. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132:873–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yancy CW. COVID‐19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020;323:1891–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, Solo K, Yaacoub S, Schünemann HJ, Chu DK, Akl EA, El‐harakeh A, Bognanni A, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person‐to‐person transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 and COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2020;395:1973–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, O’Halloran A, Cummings C, Holstein R, Prill M, Chai SJ, Kirley PD, Alden NB, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory‐confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 — COVID‐net, 14 states, March 1–30, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:458–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Coronavirus Waivers & Flexibilities. June 25, 2020. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/about‐cms/emergency‐preparedness‐response‐operations/current‐emergencies/coronavirus‐waivers. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 22. Voils CI, Venne VL, Weidenbacher H, Sperber N, Datta S. Comparison of telephone and televideo modes for delivery of genetic counseling: a randomized trial. J Genet Couns. 2018;27:339–348. 10.1007/s10897-017-0189-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Casey Lion K, Brown JC, Ebel BE, Klein EJ, Strelitz B, Gutman CK, Hencz P, Fernandez J, Mangione‐Smith R. Effect of telephone vs video interpretation on parent comprehension, communication, and utilization in the pediatric emergency department a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:1117–1125. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Table S1

Figure S1