Abstract

Background

We report characteristics and outcomes of elderly patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) with basal septal hypertrophy and dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction.

Methods and Results

We studied 1110 consecutive elderly patients with HCM (excluding moderate or greater aortic stenosis or subaortic membrane, age 80±5 years [range, 75–92 years], 66% women), evaluated at our center between June 2002 and December 2018. Clinical and echocardiographic data, including maximal left ventricular outflow tract gradient, were recorded. The primary outcome was death and appropriate internal defibrillator discharge. Hypertension was observed in 72%, with a Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score (8.6±6); while 80% had no HCM‐related sudden cardiac death risk factors. Left ventricular mass index, basal septal thickness, and maximal left ventricular outflow tract gradient were 127±43 g/m2, 1.7±0.4 cm, and 49±31 mm Hg, respectively. A total of 597 (54%) had a left ventricular outflow tract gradient >30 mm Hg, of which 195 (33%) underwent septal reduction therapy (SRT; 79% myectomy and 21% alcohol ablation). At 5.1±4 years, 556 (50%) had composite events (273 [53%] in nonobstructive, 220 [55%] in obstructive without SRT, and 63 [32%] in obstructive subgroup with SRT). One‐ and 5‐year survival, respectively were 93% and 63% in nonobstructive, 90% and 63% in obstructive subgroup without SRT, and 94% and 84% in the obstructive subgroup with SRT. Following SRT, there were 5 (2.5%) in‐hospital deaths (versus an expected Society of Thoracic Surgeons mortality of 9.2%).

Conclusions

Elderly patients with HCM have a high prevalence of traditional cardiovascular rather than HCM risk factors. Longer‐term outcomes of the obstructive SRT subgroup were similar to a normal age‐sex matched US population.

Keywords: elderly, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, outcomes

Subject Categories: Cardiomyopathy, Hypertrophy

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ASA

alcohol septal reduction

- HCM

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- SAM

systolic anterior motion

- SCD

sudden cardiac death

- SRT

septal reduction therapy

- STS

Society of Thoracic Surgeons

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

In a large group (n=1110) of elderly patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with basal septal hypertrophy and dynamic left ventricular outflow tract, we report characteristics and longer‐term outcomes.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Elderly patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy were more likely to have traditional cardiovascular risk factors, as opposed to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association hypertrophic cardiomyopathy sudden cardiac death risk factors with a low European Society of Cardiology hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 5‐year sudden cardiac death risk score.

Half the patients had significant dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, while one‐third of those underwent septal reduction therapy for relief of intractable symptoms with a low observed (versus expected) in‐hospital mortality, despite their advanced age.

The longer‐term outcomes of the obstructive septal reduction therapy subgroup were similar to a normal age‐sex matched US population.

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) has a varied phenotypic expression, ranging from asymptomatic to congestive heart failure to sudden death, which occurs in <1%/year. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 A characteristic finding in HCM is dynamic left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction and concomitant mitral regurgitation 5 attributable to systolic anterior motion (SAM) of the mitral valve, which often results in symptomatic congestive heart failure, reduced exercise capacity, and exertional syncope. With increased awareness and improvements in imaging techniques, the characteristic pathophysiologic findings typically associated with HCM are increasingly being recognized.

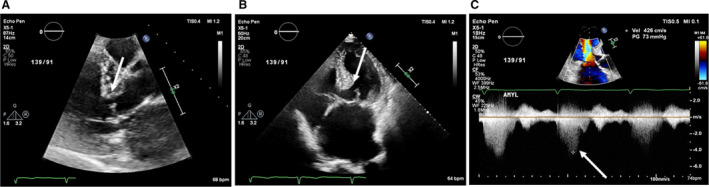

While many of the features of HCM, especially basal septal hypertrophy, SAM, and dynamic LVOT obstruction, are also observed in elderly symptomatic patients, it is also recognized that these patients have a distinct morphologic appearance and a potentially different clinical course. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Previous smaller reports have demonstrated that elderly patients with HCM‐like features predominantly tend to be women, with a high prevalence of hypertension, small LVOT, and a characteristic sigmoid‐shaped basal septum (Figure 1). In addition, patients with HCM have a steeper left ventricular (LV) inflow to outflow (LVOT‐aortic) angle, especially with increasing age, which is also independently associated with a higher dynamic LVOT gradient. 11 Overall, such patients are perceived to be at low risk for HCM‐related morbidity/mortality. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 As a result, HCM‐related sudden cardiac death (SCD) prevention therapies, especially implantable cardioverter‐defibrillators (ICDs) are generally not recommended in such patients. However, many such patients often require evaluation and treatment of advanced symptoms related to severe dynamic LVOT obstruction and intractable to maximally tolerated medical therapy. In such cases, invasive septal reduction therapies (SRTs) like alcohol septal ablation (ASA) and surgical myectomy could provide symptomatic relief. However, there are scarce data in terms of management and outcomes of elderly patients with HCM, especially taking into account management of obstructive physiology versus none. Indeed, in previous observational studies, SRT has been shown to provide excellent long‐term survival and freedom from recurrent symptoms in patients with HCM with severe dynamic LVOT obstruction. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 Because of previously demonstrated excellent outcomes of SRT at our center, 16 , 17 , 19 in a carefully selected group of severely symptomatic elderly patients with obstructive HCM‐like physiology and intolerance to maximal medical therapy, we offer SRT for symptom relief and improved quality of life. We sought to study characteristics and outcomes of elderly patients with HCM who presented to our center for evaluation and overall management.

Figure 1. Echocardiographic images of a 79‐year‐old symptomatic female with a long‐standing history of hypertension and a picture consistent with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.

A, Parasternal long‐axis image demonstrating a sigmoid‐shaped upper septal bulge with concomitant systolic anterior motion of mitral valve. (B) Four‐chamber image demonstrating a sigmoid‐shaped upper septal bulge with concomitant systolic anterior motion of mitral valve. (C) Continuous Doppler across the left ventricular outflow tract demonstrating severe dynamic obstruction.

Methods

The data, methods used in the analysis, and materials used to conduct the research will not be made available to any researcher for purposes of reproducing the results or replicating the procedure.

Study Sample

The study sample consisted of 1110 consecutive elderly HCM patients (age range 75–92 years, mean age 80±5 years, 66% women) who presented to our center between June 2002 and December 2018 for a comprehensive clinical and imaging evaluation. These patients are part of an institutional review board–approved ongoing observational registry (total n=7954; total number of SRT=2868) with waiver of individual informed consent. The diagnosis of “elderly HCM” was made by experienced cardiologists at our center on the basis of advanced age, clinical history, and typical imaging features, with LV hypertrophy (LV wall thickness ≥15 mm) in the setting of a small LV cavity, absence of LV dilation, and characteristic sigmoid‐shaped septum observed on echocardiography (Figure 1). 3 , 4 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 Presence of resting/provocable LVOT obstruction (LVOT gradient ≥30 mm Hg) also aided in the diagnosis. Because of a different pathophysiologic profile, the following patients were excluded: (1) those with a subaortic membrane (n=63) and (2) those with a mixed picture of HCM and moderate or greater aortic stenosis (n=191). By study design, younger patients with imaging findings consistent with characteristic HCM or those with an alternative diagnosis following a thorough clinical and imaging evaluation (eg, amyloidosis, ischemic cardiomyopathy) were not included in the current study. No patient was on renal replacement therapy.

Baseline clinical data were manually extracted from electronic medical records. Follow‐up information was collected by manual extraction from electronic medical records and phone calls. Presence of atrial fibrillation was recorded, based on history, ECGs, and Holter data. Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, wide complex tachycardia at ≥120 beats per minute lasting >3 beats but <30 seconds, or sustained ventricular tachycardia lasting >30 seconds was recorded, based on history and Holter data. Presence of an ICD and permanent pacemaker was ascertained. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association SCD risk factors and 5‐year European Society of Cardiology SCD risk score were also calculated. 3 , 4 In addition, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) score was also calculated.

Imaging

All patients underwent comprehensive ECGs using commercially available instruments (Philips Healthcare, Boyhell, WA; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI; and Siemens, Kensington, PA). Maximal end‐diastolic LV wall thickness, LV dimensions, and left atrial area were measured according to guidelines. 21 Characteristic late‐peaking resting LVOT maximal velocity was measured by continuous‐wave Doppler echocardiography, and pressure gradient was estimated by using a simplified Bernoulli equation. Care was taken to avoid contamination of LVOT waveform by mitral regurgitation. In addition, absence of a fixed obstruction attributable to a subaortic membrane and aortic stenosis were additionally confirmed on Doppler profile. In patients with resting LVOT gradients <30 mm Hg, provocative maneuvers including Valsalva and amyl nitrite were used. In symptomatic patients with resting peak LVOT gradient >50 mm Hg, provocative maneuvers were not used. Maximal dynamic LVOT gradient was recorded and defined as the highest recorded gradient (either resting or provoked) in a patient. 22 Degree of resting mitral regurgitation was assessed (none to severe) using multiple criteria. 23 Right ventricular systolic pressure was calculated. In patients with missing values, the archived images were retrieved, and images were analyzed.

A subgroup of patients underwent a standard contrast‐enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance examination, as described previously, and presence or absence of late gadolinium enhancement was ascertained. 24

Septal Reduction Therapy

We recorded the date and type of SRT performed in follow‐up. Surgical procedures to relieve LVOT obstruction were recorded as follows: (1) isolated myectomy and (2) myectomy+mitral valve/subvalvular apparatus surgery. Additional surgeries, including coronary artery bypass grafting, maze procedure, pulmonary vein isolation, and left atrial appendage ligation/excision were also recorded. Details of surgical techniques by our group have been described previously. 13 , 16 , 17 , 25 The basic technique of myectomy involved muscle resection below the membranous septum, removing muscle over both papillary muscles, and often extending to both trigones.

Patients meeting the criteria for SRT but deemed high risk for surgical relief of LVOT obstruction were carefully selected for ASA, after ascertaining adequacy of septal perforator anatomy on invasive angiography. The details of the ASA technique by our group has been described previously. 19

Outcomes Assessment

The duration of follow‐up ranged between initial outpatient visit to event/last follow‐up. Death notification was confirmed by observation of the death certificate or verified with a family member. To ascertain complete follow‐up, in addition to in‐person outpatient visits and phone call follow‐up, we queried individual state and nationally available databases and performed extensive obituary searches. The last query was performed in June 2019. The cause of death was ascertained as cardiac death, unknown, or noncardiac death, after review of records and discussion with family. In addition, we recorded successful resuscitation from cardiac arrest or appropriate ICD shocks (with defibrillation threshold of >200 beats on electrogram reviews at our institution). 26 Given the study sample (elderly patients), we chose all‐cause death and appropriate ICD discharge as the primary composite end point. We also studied a secondary composite end point, which included cardiac death (excluding documented noncardiac death attributable to cancer, liver failure, or primary respiratory or neurologic issues but censoring at the time of event), unknown cause of death, and appropriate ICD discharge. Patients with an unknown cause of death were included as part of the secondary composite outcome, unless the patient's proximal history, just before death, strongly suggested a noncardiac cause based on chart documentation or discussion with family. 27 In addition, presence of stroke (transient or permanent) in the SRT subgroup was recorded on the basis of clinical neurologic evaluation and appropriate neuroimaging.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±SD or median (with interquartile range) and compared using ANOVA (normal distribution) or Mann‐Whitney test (nonnormal distribution), as appropriate. Categorical data are expressed as percentage and compared using chi‐square. To assess for the association of various predictors with longer‐term primary composite outcomes (all‐cause mortality and appropriate ICD discharge), multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed, and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs were calculated. Cox proportional hazard assumptions were checked by Schoenfeld residuals. All survival analysis was performed separately in obstructive and nonobstructive subgroups. For univariable analysis, relevant variables that are known to be associated with outcomes were studied. Variables that had a significant (P<0.05) association with primary events on univariable analysis were subsequently considered for the multivariable model. Additionally, Kaplan‐Meier curves were generated to determine the cumulative proportion of patients with events as a function over time, and compared using log‐rank or the generalized Wilcoxon statistic, as appropriate. In addition, the survival was also compared with the survival of an age‐sex matched US population (www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/life_tables). The discriminative ability of survival models for longer‐term composite primary events were compared using log‐likelihood ratios. Since longer‐term secondary composite events and noncardiac death were competing risks, survival analysis was performed by competing risk regression analysis using the Fine‐Gray proportional subhazards model, and subdistribution HRs were calculated, along with 95% CI. 28 , 29 Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and R 3.4.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The clinical and imaging data of the study sample as a whole, as well as separated on basis of obstructive (n=597, 54%) versus nonobstructive physiology (n=513, 46%), are shown in Tables 1and 2. Of those with obstructive physiology, 195 (33%) subsequently underwent SRT, with details as discussed below. By study design, patients were significantly older (mean age, 80±5 years) than standard patients with HCM, and 727 (66%) were women, with no significant differences within subgroups. The number of traditional HCM‐related risk factors were low and standard cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension (n=795; 72%) and hyperlipidemia (n=759; 68%), were high, with no significant differences within subgroups. A total of 325 (31%) of the patients had a history of atrial fibrillation/flutter (10% were in atrial fibrillation/flutter at the time of presentation), with an expectedly higher proportion in the obstructive subgroup who underwent SRT. The vast majority of the patients had no American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association SCD risk factors (N=896; 80%) and the European Society of Cardiology HCM 5‐year SCD risk score was low (mean, 1.54±1.2). However, these risk factors were significantly higher in the obstructive subgroup who underwent SRT. The mean STS score was high (8.6±6) in the study sample (likely driven by higher age and a greater burden of cardiovascular comorbidities); however, there were no differences within subgroups. had preserved LV ejection fraction (>50%) and LV mass index was significantly increased (127±43 g/m2), while the indexed LV cavity size were small (0.9±0.3 cm/m2). A total of 684 (62%) patients had SAM of the mitral valve (ranging from nonobstructive cordal SAM to severe leaflet SAM), while 597 (54%) had evidence of significant dynamic LVOT obstruction with a maximal LVOT gradient >30 mm Hg. In the study sample, 194 (10%) patients also underwent cardiovascular magnetic resonance, of which 100 (52%) had evidence of late gadolinium enhancement, with no difference between subgroups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample

| Variable | Total (N=1110) | Nonobstructive (N=513) | Obstructive (N=597) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No SRT in Follow‐Up (N=402) | SRT in Follow‐Up (N=195) | ||||

| Age, y | 80±5 | 80±5 | 80±5 | 79±5 | 0.11 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 727 (66) | 333 (65) | 265 (66) | 129 (66) | 0.39 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 795 (72) | 357 (70) | 288 (72) | 140 (72) | 0.18 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 759 (68) | 619 (68) | 140 (72) | 140 (72) | 0.15 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 189 (17) | 97 (19) | 61 (15) | 31 (16) | 0.33 |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 129 (12) | 73 (14%) | 42 (10%) | 14 (7%) | 0.02 |

| COPD | 141 (13) | 73 (14) | 48 (12) | 20 (10) | 0.31 |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 113 (10) | 94 (10) | 19 (10) | 19 (10) | |

| Documented CAD, n (%) | 119 (11) | 41 (8) | 40 (10) | 38 (20) | 0.01 |

| Genetic testing for HCM,* n (%) | 38 (3) | 17 (3) | 13 (3) | 8 (4) | 0.27 |

| Family history of HCM, n (%) | 19 (2) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 9 (5) | 0.003 |

| Family history of SCD, n (%) | 52 (5) | 14 (3) | 21 (5) | 17 (9) | 0.003 |

| History of SCD, n (%) | 9 (0.8) | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0.83 |

| History of NSVT, n (%) | 78 (7) | 31 (6) | 2270 (7) | 20 (10) | 0.14 |

| History of syncope, n (%) | 133 (12) | 75 (15) | 12 (3), none exertional | 46 (24) | 0.009 |

| History of AF, n (%) | 325 (31) | 174 (34) | 90 (22) | 61 (31) | <0.001 |

| AF on baseline ECG, n (%) | 102 (10) | 66 (13) | 25 (6) | 11 (6) | 0.03 |

| History of prior alcohol septal ablation, n (%) | 43 (4) | 16 (3) | 0 | 27 (14) | <0.001 |

| History of prior surgical myectomy, n (%) | 35 (3%) | 19 (4%) | 9 (2%) | 7 (4%) | 0.42 |

| Implantable defibrillator, n (%) | 34 (3) | 20 (4) | 10 (3) | 4 (2) | 0.31 |

| Permanent pacemaker, n (%) | 75 (7) | 20 (4) | 20 (5) | 35 (18) | <0.001 |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 724 (65) | 554 (61) | 170 (87) | 170 (87) | <0.001 |

| Beta‐blockers, n (%) | 899 (81) | 389 (76) | 335 (83%) | 175 (90) | <0.01 |

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 221 (20) | 84 (16) | 74 (18) | 64 (33) | <0.001 |

| Disopyramide, n (%) | 31 (3) | 9 (2) | 3 (6) | 11 (6) | 0.01 |

| Anticoagulation, n (%) | 272 (25) | 141 (27) | 60 (15) | 71 (36) | <0.001 |

| Angina, n (%) | 431 (19) | 114 (12) | 317 (24) | 317 (24) | <0.001 |

| NYHA class, n (%) | |||||

| I | 130 (12) | 66 (13) | 64 (16) | 0 | |

| II | 763 (69) | 405 (79) | 338 (84) | 20 (10) | <0.001 |

| III | 192 (17) | 37 (7) | 0 | 155 (80) | |

| IV | 25 (2) | 5 (1) | 0 | 0 (10) | |

| Society of Thoracic Surgeons score | 8.6±6 | 8.6±7 | 8.1±15 | 9.2±17 | 0.144 |

| ACC/AHA SCD risk factors, n (%) | |||||

| 0 | 896 (80) | 426 (83) | 330 (82) | 140 (72) | |

| 1 | 195 (18) | 80 (16) | 67 (17) | 48 (25) | 0.01 |

| ≥2 | 19 (2) | 7 (1) | 5 (1) | 7 (3) | |

| ESC % 5‐y SCD risk score | 1.54±1.2 | 1.11±0.7 | 1.6±1 | 2.4±2 | <0.001 |

| ESC % 5‐y SCD risk categories, n (%) | |||||

| Low risk (<4%) | 1052 (95) | 506 (99) | 381 (95) | 1654 (85) | |

| Intermediate risk (4%–6%) | 44 (4) | 7 (1) | 15 (4) | 22 (11) | <0.001 |

| High risk (>6%) | 14 (1%) | 0 | 6 (2%) | 8 (4%) | |

ACC/AHA indicates American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; AF, atrial fibrillation; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SCD, sudden cardiac death; and SRT, septal reduction therapy.

No patients were genotype positive for HCM.

Table 2.

Imaging Characteristics of the Study Sample

| Variable | Total (N=1110) | Nonobstructive (N=513) | Obstructive (N=597) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No SRT in Follow‐Up (N=02) | SRT in Follow‐Up (N4=195) | ||||

| LV ejection fraction, % | 62±5 | 61±6 | 62±6 | 62±5 | 0.18 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 127±43 | 124±40 | 125±45 | 141±45 | <0.001 |

| Indexed LV end‐diastolic dimension. cm/m2 | 1.9±0.3 | 1.9±0.4 | 1.9±0.4 | 1.9±0.3 | 0.72 |

| Indexed LV end‐systolic dimension, cm/m2 | 0.9.0±0.3 | 1.0±0.3 | 0.9±0.3 | 0.9±0.4 | 0.54 |

| Maximal LV thickness, cm | 1.7±0.4 | 1.6±0.3 | 1.7±0.4 | 1.9±0.4 | <0.001 |

| Maximal posterior wall thickness, cm | 1.2±0.3 | 1.1±0.3 | 1.2±0.3 | 1.2±0.4 | 0.23 |

| Indexed left atrial dimensions, cm/m2 | 2.4±0.3 | 2.4±0.4 | 2.3±0.4 | 2.3±0.3 | 0.62 |

|

Moderate or greater resting mitral regurgitation, n (%) Trivial‐mild |

302 (27 | 94 (18) | 120 (30) | 88 (45) | <0.001 |

| SAM of mitral valve, n (%) | 684 (62) | 87 (17) | |||

| Cordal SAM only, n (%) | 402 (100) | 195 (100) | <0.001 | ||

| Resting LVOT gradient, mm Hg | 35±34 | 8±9 | 44±22 | 63±32 | <0.001 |

| Resting LVOT gradient ≥30 mm Hg, n (%) | 405 (37) | 0 | 279 (69) | 126 (65) | <0.001 |

| Maximal LVOT gradient, mm Hg | 49±31 | 9±8 | 82±43 | 87±14 | <0.001 |

| Maximal LVOT gradient ≥30 mm Hg, n (%) | 597 (54) | 0 | 402 (100) | 195 (100) | <0.001 |

| Maximal LVOT gradient ≥50 mm Hg, n (%) | 496 (45) | 0 | 301 (100) | 195 (100) | <0.001 |

| Right ventricular systolic pressure, mm Hg | 36±14 | 35±13 | 35±15 | 38±17 | 0.01 |

| Late gadolinium enhancement on cardiovascular magnetic resonance, n (%) | 100/194 (52) | 31/58 (53) | 25/53 (47) | 44/83 (53) | <0.01 |

LV indicates left ventricular; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; and SAM, systolic anterior motion.

In the study sample, 195 patients (18% of the total sample and 33% of the obstructive subgroup) underwent SRT during follow‐up at a median time of 29 days following initial evaluation. Of these, 90% were in New York Heart Association class III/IV. The remaining 10% had additional concomitant symptoms (exertional syncope in the setting of severe dynamic LVOT obstruction and intractable angina) as an indication for SRT. On the other hand, in the obstructive but non‐SRT subgroup, 84% had only mild symptoms (New York Heart Association class II), and the patients were not deemed to reach the threshold for SRT. The type of SRT procedures were as follows: (1) isolated myectomy (n=84; 43%), (2) myectomy plus mitral valve repair (n=56; 29%), (3) myectomy plus mitral valve replacement (n=14; 7%), and (4) ASA (n=41; 21%). In addition, in the surgical subgroup, 38 (25%) patients underwent concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting, and 34 (22%) underwent a maze procedure, while 22 (14%) had left atrial appendage ligation. Of the entire study sample, 78 (7%) patients had SRT performed before referral to our center (43 ASA and 35 surgical myectomies). Within this subgroup, 27 patients with a prior ASA and 7 patients with a prior myectomy needed a follow‐up surgical myectomy to relieve symptomatic and persistently severe dynamic LVOT obstruction. The median in‐hospital length of stay for the SRT procedure was 9 days (interquartile range, 6–14 days). A predischarge echocardiogram revealed relief of LVOT obstruction (mean LVOT gradient, 10±7 mm Hg) in all patients. There were no documented ventricular septal defects. During follow‐up, there were an additional 75 (7%) patients with pacemaker implantation. The proportion was significantly higher in the subgroup with SRT (including all patients with prior ASA who underwent surgical myectomy). Also, there were 23 (2%) patients with new ICDs, and 36 (3%) patients who developed new‐onset atrial fibrillation (excluding short‐term postoperative atrial fibrillation) during follow‐up, with no difference between subgroups.

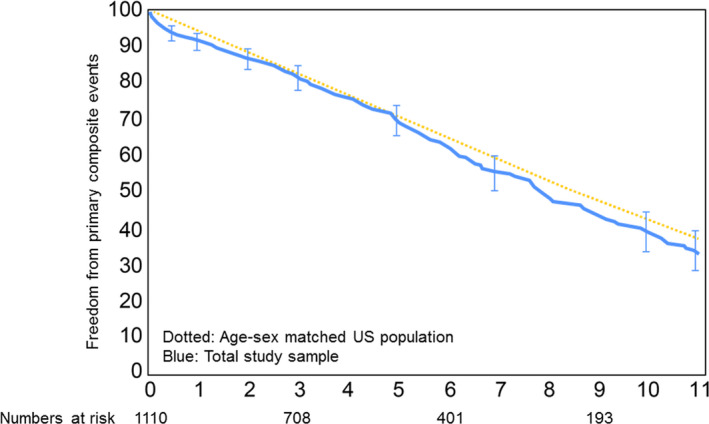

During a mean follow‐up of 5.1±4 years (median, 4.4 years with interquartile range of 2.0–7.6 years), 556 patients (50%) met the composite primary end point. The composite primary outcome included the following: 551 (50%) deaths and 6 (0.5%) appropriate ICD discharges. An additional 21 (2%) patients died of documented noncardiac causes during follow‐up and were excluded from the secondary composite survival analysis (n=535) but were censored at the time of death. In patients who developed multiple end points, time to first event was used as an event time cutoff. The longer‐term primary composite outcomes of the entire study sample were similar to an age‐sex matched normal US population, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier survival curves demonstrating long‐term primary outcomes of the entire study sample, compared with age‐sex–matched normal US population.

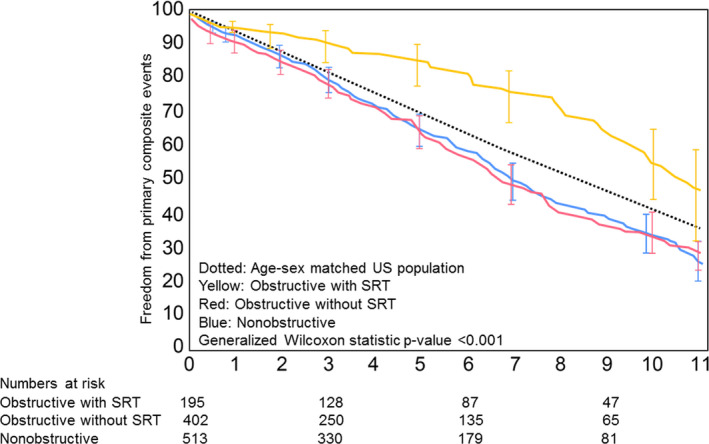

Because of (1) different pathophysiologic profiles of the obstructive and nonobstructive subgroups and (2) potential significant impact of SRT in the obstructive subgroup, additional survival analyses were performed separately in these subgroups. The breakdown of longer‐term composite primary end points in 3 subgroups was as follows: 273 (53%) in the nonobstructive subgroup, 220 (55%) in the obstructive subgroup without SRT, and 63 (32%) in the obstructive subgroup who underwent SRT. The Kaplan‐Meier survival curves of the 3 subgroups, along with comparison to an age‐sex matched US population, are shown in Figure 3. Longer‐term survival of patients who underwent SRT was significantly better than for patients who did not undergo SRT. Respective 1, 2, and 5‐year freedom from primary composite events for each subgroup were as follows: (1) 93%, 86%, and 63% in the nonobstructive subgroup; (2) 90%, 84%, and 63% in the obstructive subgroup without SRT; and (3) 94%, 93%, and 84% in the obstructive subgroup with SRT. Within the SRT subgroup, there were 5 (2.5%) in‐hospital deaths (versus an expected postoperative mortality rate of 9.2% on the basis of the STS score) and 2 (1%) strokes before postoperative discharge.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier survival curves demonstrating long‐term primary outcomes of the entire study sample, compared with age‐sex–matched normal US population and separated into 3 subgroups as follows: nonobstructive, obstructive without SRT, and obstructive with SRT.

SRT indicates septal reduction therapy.

The data on univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard survival analyses in the obstructive and nonobstructive subgroups are shown in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. In the obstructive subgroup (Table 3), age (HR, 1.09), chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.95), history of atrial fibrillation (HR, 1.75), and resting right ventricular systolic pressure (HR, 1.16) were associated with worse longer‐term primary events (all P<0.01), while SRT during follow‐up was associated with significantly improved primary outcomes (HR, 0.58; P<0.001). Presence of symptoms (New York Heart Association class II or higher) and higher basal septal thickness were associated with “improved” outcomes on univariable analysis, attributable to an interaction with SRT, which was associated with improved outcomes. Similarly, in the nonobstructive subgroup (Table 4), age (HR, 1.09), chronic kidney disease (HR, 1.63), history of atrial fibrillation (HR, 1.36) and higher LV wall thickness (HR, 2.10) were associated with primary composite events (all P<0.05). Data on the incremental prognostic utility of various relevant risk factors in the obstructive and nonobstructive subgroups are shown in Table 5.

Table 3.

Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis for the Composite End Point of All‐Cause Mortality and Appropriate ICD Discharge in the Obstructive Study Sample

| Variable | Obstructive Subgroup (n=597, Number of Events 283) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age (for every 1‐y increase) | 1.09 (1.07–1.11) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.06–1.12) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.20 (0.92–1.58) | 0.17 | ||

| History of hypertension | 1.33 (0.97–1.72) | 0.23 | ||

| History of dyslipidemia | 1.35 (0.94–1.69) | 0.32 | ||

| History of diabetes mellitus | 1.12 (0.79–1.59) | 0.52 | ||

| History of chronic kidney disease | 2.4 (1.59–3.12) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.36–2.80) | <0.001 |

| History of obstructive CAD | 2.01 (1.14–3.54) | 0.01 | 1.14 (0.61–2.12) | 0.69 |

| History of COPD | 1.13 (0.95–2.01) | 0.35 | ||

| History of atrial fibrillation | 1.79 (1.36–2.35) | <0.001 | 1.75 (1.32–2.32) | <0.001 |

| Syncope | 0.78 (0.54–1.10) | 0.15 | ||

| NYHA class I vs ≥II* | 0.67 (0.34–0.93) | <0.01 | 0.97 (0.68–1.23) | 0.34 |

| Family history of HCM | 1.87 (0.68–5.12) | 0.21 | ||

| Family history of SCD | 1.32(0.79–2.39) | 0.34 | ||

| Medical therapy for HCM | 0.81 (0.60–1.10) | 0.18 | ||

| History of NSVT | 1.31 (0.79–2.16) | 0.28 | ||

| ESC risk score | 1.11 (0.98–1.25) | 0.12 | ||

| Society of Thoracic Surgeons score (for 1% increase) † | 1.52 (1.25–2.01) | <0.001 | ||

| ACC/AHA risk factors (0 vs ≥1) | 1.21 (0.90–1.61) | 0.19 | ||

| LV ejection fraction | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.98 | ||

| Maximal LV thickness* | 0.89 (0.79–0.96) | 0.01 | 1.06 (0.96–1.14) | 0.29 |

| Indexed left atrial size | 1.06 (0.90–1.25) | 0.46 | ||

| Moderate or greater mitral regurgitation | 1.17 (0.91–1.51) | 0.20 | ||

| Maximal LVOT gradient (for every 10 mm Hg increase) | 1.01 (0.99–1.02) | 0.26 | ||

| Indexed LV mass (for every 10 g/m2 increase) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 0.03 | ||

| Indexed LV end‐systolic diameter (for every 10 mm/m2 increase) | 1.01 (0.97–1.05) | 0.80 | ||

| RVSP (for every 10 mm Hg increase) | 1.16 (1.07–1.26) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.03–1.23) | 0.004 |

| Septal reduction therapy | 0.50 (0.37–0.66) | <0.001 | 0.58 (0.42–0.79) | <0.001 |

ACC/AHA indicates American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HR, hazard ratio; ICD, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator; LV, left ventricular; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; and SCD, sudden cardiac death.

Maximal LV wall thickness and NYHA Class did not maintain statistical significance in the multivariable model with septal reduction therapy.

When Society of Thoracic Surgeons score was replaced in the multivariable analysis instead of its various constituent elements, the findings were similar.

Table 4.

Cox Proportional Hazards Analysis for the Composite End Point of All‐Cause Mortality and Appropriate ICD Discharge in the Nonobstructive Study Sample

| Variable | Nonobstructive Subgroup (n=513, Number of Events 273) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age (for every 1‐y increase) | 1.09 (1.07–1.12) | <0.001 | 1.09 (1.07–1.12) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.13 (0.88–1.44) | 0.32 | ||

| History of hypertension | 1.22 (0.94–1.58) | 0.13 | ||

| History of dyslipidemia | 1.27 (0.89–1.75) | 0.41 | ||

| History of diabetes mellitus | 1.07 (0.78–1.48) | 0.67 | ||

| History of chronic kidney disease | 1.73 (1.26–2.39) | <0.001 | 1.63 (1.19–2.25) | <0.001 |

| History of obstructive CAD | 1.21 (0.78–1.88) | 0.37 | ||

| History of COPD | 1.05 (0.89–1.94) | 0.42 | ||

| History of atrial fibrillation | 1.48 (1.14–1.92) | 0.002 | 1.36 (1.05–1.77) | 0.02 |

| Syncope | 1.15 (0.91–1.61) | 0.32 | ||

| NYHA class I vs ≥II | 1.19 (1.03–1.54) | 0.01 | 1.13 (1.02–1.68) | 0.03 |

| Family history of HCM | 1.56 (0.60–3.29) | 0.35 | ||

| Family history of SCD | 2.05 (0.64–6.56) | 0.21 | ||

| Medical therapy for HCM | 0.77 (0.58–1.02) | 0.06 | ||

| History of NSVT | 1.40 (0.52–3.79) | 0.48 | ||

| Society of Thoracic Surgeons score (for 1% increase)* | 1.72 (1.31–2.13) | <0.001 | ||

| ESC risk score | 1.26 (0.84–1.88) | 0.34 | ||

| ACC/AHA risk factors (0 vs ≥1) | 1.57 (0.95–2.59) | 0.19 | ||

| LV ejection fraction | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.98 | ||

| Maximal LV thickness | 2.42 (1.67–3.53) | <0.001 | 2.10 (1.46–3.00) | <0.001 |

| Indexed left atrial size | 1.04 (0.87–1.32) | 0.52 | ||

| Moderate or greater mitral regurgitation | 1.17 (0.87–1.58) | 0.29 | ||

| Maximal LVOT gradient (for every 10 mm Hg increase) | 1.13 (0.98–1.13) | 0.11 | ||

| Indexed LV mass (for every 10 g/m2 increase) † | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 0.002 | ||

| Indexed LV endsystolic diameter (for every 10 mm/m2 increase) | 1.01 (0.96–1.04) | 0.76 | ||

| RVSP (for every 10 mm Hg increase) | 1.13 (1.02–1.25) | 0.01 | 1.05 (0.95–1.16) | 0.29 |

ACC/AHA indicates American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HR, hazard ratio; ICD, implantable cardioverter‐defibrillator; LV, left ventricular; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; NYHA, New York Heart Association; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; and SCD, sudden cardiac death.

When Society of Thoracic Surgeons score (a composite of known cardiovascular risk factors) was replaced in the multivariable analysis instead of its various constituent elements, the findings were similar.

When indexed LV mass was substituted for maximal LV wall thickness in multivariable analysis, the findings were similar.

Table 5.

Incremental Prognostic Value of Various Predictors for Composite Primary Events

| Variable | Log‐Likelihood Ratio | Chi‐Square | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obstructive subgroup | |||

| Clinical (increasing age+CKD)* | −1520.6 | ||

| Clinical+atrial fibrillation | −1510.4 | 20.42 | <0.001 |

| Clinical+atrial fibrillation+RVSP | −1507.8 | 5.14 | 0.02 |

| Clinical+atrial fibrillation+RVSP+septal reduction therapy † | −1498.9 | 17.86 | <0.001 |

| Nonobstructive subgroup | |||

| Clinical (increasing age+NYHA class 1 vs ≥ II+CKD)* | −1423.5 | ||

| Clinical+atrial fibrillation | −1418.7 | 9.52 | 0.002 |

| Clinical+atrial fibrillation+maximal maximal LV wall thickness ‡ | −1411.2 | 15.23 | <0.001 |

CKD indicates chronic kidney disease; LV, left ventricular; and NYHA, New York Heart Association.

When Society of Thoracic Surgeons score was replaced instead of the clinical model, the findings were similar.

Maximal LV wall thickness and NYHA class did not maintain statistical significance in the multivariable model with septal reduction therapy.

If LV mass index was substituted for LV wall thickness, the findings were similar.

On multivariable competing risk survival analysis for secondary composite end points (n=535), the findings were similar, as shown in Table S1.

Discussion

The current study describes characteristics and outcomes of elderly patients with HCM evaluated at our tertiary care center. As would be expected, these patients were significantly older than standard patients with HCM, with the majority being women. There was a high incidence of hypertension and other standard cardiovascular risk factors. On the other hand, the vast majority of the patients had no American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association SCD risk factors, and the European Society of Cardiology HCM 5‐year SCD risk score was low; however, almost one‐third of the patients had a history of atrial fibrillation. All patients had a significantly increased LV mass index, small indexed LV cavity size, and characteristic sigmoid‐shaped basal septal hypertrophy (Figure 1). Almost two‐thirds of patients had SAM of the mitral valve, and one‐half had significant dynamic LVOT obstruction. Within this obstructive subgroup, one‐third of patients underwent SRT for relief of intractable symptoms associated with dynamic LVOT obstruction, with an in‐hospital mortality rate of 2.5%. While observed in‐hospital mortality was higher than what was previously described in standard (younger) patients with HCM, 2 , 3 , 4 , 30 it was significantly lower compared with the mortality expected based on the average STS score of 9.2% in the operated subgroup (which itself was higher likely related to the advanced age of the study sample).

Given the advanced age of the study sample, the annualized longer‐term event rate was high, at ≈10%/year in the nonobstructive subgroup (as well as the obstructive subgroup who did not undergo SRT during follow‐up). But the longer‐term survival was significantly better at ≈6%/year in the obstructive subgroup that underwent SRT, similar to a normal age‐sex–matched US population. In the nonobstructive subgroup, higher age, atrial fibrillation, and higher LV wall thickness (or LV mass index) were associated with a higher proportion of longer‐term primary events, providing incremental prognostic value. In the obstructive subgroup, along with higher age and atrial fibrillation, higher right ventricular systolic pressure was associated with longer‐term primary events, while SRT was associated with lower primary events (and provided incremental prognostic value). Of note, presence of symptoms (New York Heart Association class II or higher) and higher basal septal thickness were associated with “improved” outcomes on univariable analysis, likely attributable to the fact that such patients were more likely to be offered SRT, which was associated with improved outcomes. As the STS score is a composite of many known risk factors associated with longer‐term mortality, a higher score was also associated with worse longer‐term outcomes in both obstructive and nonobstructive subgroups. One can argue that the reason for better outcomes in the SRT subgroup was driven by selection of “lower‐risk” individuals. However, the STS score was similar in all subgroups. In the current study, female sex and coronary artery disease did not maintain independent significance on survival analysis. In a previous report, female sex was associated with a higher longer‐term event rate, likely because of including a broader population of elderly and standard patients with HCM. 31

Many of the features of HCM, especially septal hypertrophy, SAM, and dynamic LVOT obstruction, are also observed in elderly patients who present with dyspnea and exertional syncope. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 However, it is also recognized that these patients have a distinct morphologic appearance and a potentially different clinical course. The current large study confirms observations from previous smaller reports that elderly patients with HCM with HCM‐like features tend to be predominantly women, with a high prevalence of hypertension, small LVOT, and a characteristic sigmoid‐shaped basal septum. 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 In addition, patients with HCM have a steeper LV inflow to outflow (LVOT‐aortic) angle, especially with increasing age, and this angle was independently associated with a higher dynamic LVOT gradient. 11 It appears that in this group of elderly patients, there may be multiple morphologic reasons to develop LVOT obstruction and an abnormal dynamic gradient. While such patients appear to be at a lower risk for HCM‐related morbidity/mortality, many such patients are often referred for SRT to treat advanced LVOT obstruction–related symptoms, intractable to maximally tolerated medical therapy. Data on outcomes related to SRT in such patients are scarce. Indeed, because SRT provides excellent long‐term survival and freedom from recurrent symptoms in “standard” younger patients with HCM with severe dynamic LVOT obstruction, it would be intuitive to think that similar observations would hold true in elderly patients with HCM. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 The current study demonstrates that in a carefully selected group of elderly patients with severely obstructive symptomatic HCM with intolerance to maximal medical therapy, SRT is associated with a survival that is similar to an age‐sex–matched US population.

At our center, in all elderly patients with imaging features of HCM (including dynamic LVOT obstruction), an aggressive attempt at medical therapy, including beta‐blockers and nonhydropyridine calcium channel blockers is made with periodic up‐titration as necessary to relieve symptoms. In a small proportion of patients with dynamic LVOT obstruction, disopyramide is added for added symptom relief. However, if the symptoms persist despite maximal medical therapy (or if there is medication intolerance and persistent symptoms), SRT is offered after careful assessment of procedural risk. While there are small studies on disopyramide 32 and emerging data on novel therapeutic agents that can modulate dynamic LVOT obstruction, 33 currently, there are no large‐scale studies that have demonstrated that medical therapy is associated with a symptomatic and potentially survival benefit in patients with symptomatic LVOT obstruction. As such, SRT remains the primary option for symptom relief and improving quality of life. As surgical myectomy provides excellent long‐term survival and freedom from symptoms, 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 current guidelines give it a class I indication in patients with symptomatic obstructive HCM, intractable to maximal medical therapy. 3 , 4 However, elderly patients with HCM were not adequately represented in the studies on which these recommendations are based. While there are published data on excellent outcomes of ASA in higher‐risk and elderly patients, it needs to be emphasized that a successful ASA requires a skillful operator to obtain optimal results. 18 , 19 , 20 However, any suggestion of performing SRT in an elderly patient must be balanced against procedural risk and overall experience of the center at managing these complex patients. The current study also highlights the importance of experience in invasive management of patients with HCM with severe LVOT obstruction. 16 , 17 A recent analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample demonstrated a 30‐day mortality of 6% in all patients with HCM undergoing surgical myectomy for relief of LVOT obstruction. 34 These results strongly suggest the importance of having these procedures performed at experienced centers. 7 , 9 , 11 , 17 , 19 , 20

Limitations

This was an observational study from a single tertiary center, which could have potential selection bias. The results of all testing were available to all clinicians at the time of decision making, introducing further bias. The current study tests only associations, not causality. In our clinical practice, we typically do not refer elderly patients with HCM for genetic counseling; hence, the data are not available in the vast majority of the study sample. Also, it is likely that the imaging features observed in these patients could be a result of alternate etiologies (eg, hypertension). However, the management, especially of dynamic LVOT obstruction, is typically similar to younger patients with obstructive HCM. While it was clinically excluded, it is conceivable that some elderly patients might also have concomitant amyloidosis that went unrecognized. 35 A systematic assessment of quality of life was not available in this study sample and, hence, not reported. However, we have reported those data in HCM previously. 19 To truly understand the impact of SRT versus watchful waiting on outcomes, a large‐scale prospective study would have to be conducted in patients with HCM with severe LVOT obstruction. However, a prospective, randomized trial of SRT in HCM has many inherent challenges. 36 In addition, given the overall expertise involved with both the conservative and invasive management of HCM, our results might not be generalizable to other, lesser experienced centers. 34 Not all patients were consistently followed up at our center, and it is conceivable that there were some who were lost to follow‐up, despite the extensive search that we conducted using publicly available databases. For this elderly study sample, we chose all‐cause mortality as the primary outcome because it is more objective. 37 However, the basic results were similar if the secondary outcomes were studied.

Conclusions

In a large group of elderly patients with HCM evaluated at our center, we demonstrate that they were more likely to have traditional cardiovascular risk factors, as opposed to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association HCM SCD risk factors with a low European Society of Cardiology HCM 5‐year SCD risk score. In the study, one‐half of the patients had significant dynamic LVOT obstruction, while one‐third of those underwent SRT for relief of intractable symptoms with a low observed (versus expected) in‐hospital mortality, despite their advanced age. The longer‐term outcomes of the obstructive SRT subgroup were similar to a normal age‐sex–matched US population. However, the outcomes of the obstructive subgroup who did not undergo SRT and the nonobstructive subgroups were much worse than normal age‐sex–matched US population. These findings need additional validation.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

Dr Desai is supported by the Haslam Family endowed chair in cardiovascular medicine. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Table S1

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e018527. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018527.)

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

See Editorial by Lee and Rakowski

References

- 1. Maron BJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287:1308–1320. 10.1001/jama.287.10.1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elliott P, McKenna WJ. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 2004;363:1881–1891. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16358-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gersh BJ, Maron BJ, Bonow RO, Dearani JA, Fifer MA, Link MS, Naidu SS, Nishimura RA, Ommen SR, Rakowski H, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2011;124:e783–e831. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318223e2bd [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, Borggrefe M, Cecchi F, Charron P, Hagege AA, Lafont A, Limongelli G, Mahrholdt H, et al. 2014 ESC guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2733–2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maron MS, Olivotto I, Betocchi S, Casey SA, Lesser JR, Losi MA, Cecchi F, Maron BJ. Effect of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction on clinical outcome in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:295–303. 10.1056/NEJMoa021332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lever HM, Karam RF, Currie PJ, Healy BP. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the elderly. Distinctions from the young based on cardiac shape. Circulation. 1989;79:580–589. 10.1161/01.CIR.79.3.580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lewis JF, Maron BJ. Elderly patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a subset with distinctive left ventricular morphology and progressive clinical course late in life. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:36–45. 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90545-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maron BJ, Rowin EJ, Maron MS, Braunwald E. Achieving extended longevity and quality of life for senior patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: what is possible. Am J Med. 2017;130:1236–1237. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maron BJ, Rowin EJ, Casey SA, Haas TS, Chan RH, Udelson JE, Garberich RF, Lesser JR, Appelbaum E, Manning WJ, et al. Risk stratification and outcome of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy >=60 years of age. Circulation. 2013;127:585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Topol EJ, Traill TA, Fortuin NJ. Hypertensive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy of the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:277–283. 10.1056/NEJM198501313120504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kwon DH, Smedira NG, Popovic ZB, Lytle BW, Setser RM, Thamilarasan M, Schoenhagen P, Flamm SD, Lever HM, Desai MY. Steep left ventricle to aortic root angle and hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: study of a novel association using three‐dimensional multimodality imaging. Heart. 2009;95:1784–1791. 10.1136/hrt.2009.166777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ommen SR, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Maron MS, Cecchi F, Betocchi S, Gersh BJ, Ackerman MJ, McCully RB, Dearani JA, et al. Long‐term effects of surgical septal myectomy on survival in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:470–476. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smedira NG, Lytle BW, Lever HM, Rajeswaran J, Krishnaswamy G, Kaple RK, Dolney DO, Blackstone EH. Current effectiveness and risks of isolated septal myectomy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:127–133. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.07.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Woo A, Williams WG, Choi R, Wigle ED, Rozenblyum E, Fedwick K, Siu S, Ralph‐Edwards A, Rakowski H. Clinical and echocardiographic determinants of long‐term survival after surgical myectomy in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;111:2033–2041. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000162460.36735.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ball W, Ivanov J, Rakowski H, Wigle ED, Linghorne M, Ralph‐Edwards A, Williams WG, Schwartz L, Guttman A, Woo A. Long‐term survival in patients with resting obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy comparison of conservative versus invasive treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2313–2321. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Desai MY, Bhonsale A, Smedira N, Naji P, Thamilarasan M, Lytle B, Lever H. Predictors of long term outcomes in symptomatic hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy patients undergoing surgical relief of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Circulation. 2013;128:209–216. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hodges K, Rivas CG, Aguilera J, Borden R, Alashi A, Blackstone EH, Desai MY, Smedira NG. Surgical management of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in a specialized hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy center. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157:2289–2299. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.11.148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sorajja P, Ommen SR, Holmes DR Jr, Dearani JA, Rihal CS, Gersh BJ, Lennon RJ, Nishimura RA. Survival after alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2012;126:2374–2380. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.076257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kwon DH, Kapadia SR, Tuzcu EM, Halley CM, Gorodeski EZ, Curtin RJ, Thamilarasan M, Smedira NG, Lytle BW, Lever HM, et al. Long‐term outcomes in high risk symptomatic patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy undergoing alcohol septal ablation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:432–438. 10.1016/j.jcin.2008.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Veselka J, Krejci J, Tomasov P, Zemanek D. Long‐term survival after alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: a comparison with general population. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2040–2045. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography’s Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kwon DH, Smedira NG, Rodriguez ER, Tan C, Setser R, Thamilarasan M, Lytle BW, Lever HM, Desai MY. Cardiac magnetic resonance detection of myocardial scarring in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: correlation with histopathology and prevalence of ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:242–249. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zoghbi WA, Enriquez‐Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, et al. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two‐dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16:777–802. 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00335-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mentias A, Raeisi‐Giglou P, Smedira NG, Feng K, Sato K, Wazni O, Kanj M, Flamm SD, Thamilarasan M, Popovic ZB, et al. Late gadolinium enhancement in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and preserved systolic function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:857–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kwon DH, Smedira NG, Thamilarasan M, Lytle BW, Lever H, Desai MY. Characteristics and surgical outcomes of symptomatic patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with abnormal papillary muscle morphology undergoing papillary muscle reorientation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:317–324. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.10.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Spirito P, Casey SA, Bellone P, Gohman TE, Graham KJ, Burton DA, Cecchi F. Epidemiology of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy‐related death: revisited in a large non‐referral‐based patient population. Circulation. 2000;102:858–864. 10.1161/01.CIR.102.8.858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, Chaitman BR, Cutlip DE, Farb A, Fonarow GC, Jacobs JP, Jaff MR, Lichtman JH, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Cardiovascular Endpoints Data Standards). Circulation. 2015;132:302–361. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scrucca L, Santucci A, Aversa F. Competing risk analysis using R: an easy guide for clinicians. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;40:381–387. 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Maron MS, Rowin EJ, Olivotto I, Casey SA, Arretini A, Tomberli B, Garberich RF, Link MS, Chan RHM, Lesser JR, et al. Contemporary natural history and management of nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1399–1409. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Geske JB, Ong KC, Siontis KC, Hebl VB, Ackerman MJ, Hodge DO, Miller VM, Nishimura RA, Oh JK, Schaff HV, et al. Women with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy have worse survival. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:3434–3440. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sherrid MV, Barac I, McKenna WJ, Elliott PM, Dickie S, Chojnowska L, Casey S, Maron BJ. Multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of disopyramide in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1251–1258. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heitner SB, Jacoby D, Lester SJ, Owens A, Wang A, Zhang D, Lambing J, Lee J, Semigran M, Sehnert AJ. Mavacamten treatment for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170:741–748. 10.7326/M18-3016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Panaich SS, Badheka AO, Chothani A, Mehta K, Patel NJ, Deshmukh A, Singh V, Savani GT, Arora S, Patel N, et al. Results of ventricular septal myectomy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (from Nationwide Inpatient Sample [1998–2010]). Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:1390–1395. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.07.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alashi A, Desai RM, Khullar T, Hodges K, Rodriguez ER, Tan C, Popovic ZB, Thamilarasan M, Wierup P, Lever HM, et al. Different histopathologic diagnoses in patients with clinically diagnosed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after surgical myectomy. Circulation. 2019;140:344–346. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.040129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Olivotto I, Ommen SR, Maron MS, Cecchi F, Maron BJ. Surgical myectomy versus alcohol septal ablation for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Will there ever be a randomized trial? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:831–834. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lauer MS, Blackstone EH, Young JB, Topol EJ. Cause of death in clinical research: time for a reassessment? J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:618–620. 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00250-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1