The incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in American youth has increased dramatically in recent decades, with Black and Hispanic youth experiencing higher rates of both. 1 , 2 Indeed, obesity prevalence among non‐Hispanic Black (22%) and Hispanic (25.8%) youth is disproportionately higher than non‐Hispanic White youth (14.1%). 1 Black and Hispanic youth also have nearly double the incidence rates of type 2 diabetes mellitus compared with non‐Hispanic White youth. 2

The food and beverage industry plays an underacknowledged role in these concerning trends. The food industry spends $1.8 billion per year marketing food and beverages to children and adolescents, with television advertising comprising the largest single share of all expenditures. 3 Over 80% of this marketing is spent on advertising foods high in saturated fat, trans fat, sugar, and sodium. 3 On average, children and teens viewed ≈10 food‐related television ads per day in 2017. 4 In turn, television food advertising has been linked to poor diet quality 5 , 6 and diet‐related diseases in children. 5 , 6 , 7 Importantly, food companies have also been reported to target advertising of nutritionally poor foods to Black and Hispanic children, 4 , 8 , 9 which may contribute to widening obesity disparities between Black and Hispanic children and their White peers.

These practices have serious population and individual health consequences, as obese children are likely to become obese adults 10 and experience increased risk of cardiovascular disease. 10 Thus, addressing the public health issue of childhood obesity, especially in Black and Hispanic youth, is of critical importance for healthcare professionals. The goals of this piece are 2‐fold: first, to discuss the role of targeted television food advertising in fueling the obesity epidemic and widening racial health disparities in children; and second, to consider thoughtful public policy options that may mitigate the hazardous impact of these practices.

History and Current State of Unhealthy Food Advertising to Black and Hispanic Youth

Traditionally, Black and Hispanic communities have been attractive populations to target for food marketing, given their increasing buying power, demographic growth, family sizes, and specific buying behaviors. 8 For almost a century, soft‐drink companies have had “special market” departments focused on ethnic minorities. 9 There is also evidence that the tobacco industry directly transferred racial/ethnic minority marketing knowledge and infrastructure to food and beverage companies in the 1980s. 11 More recently, targeted marketing of less healthy foods and beverages to the Black community has also been documented in the context of this population’s limited access to chain supermarkets, healthful foods within markets, and increased number of fast‐food restaurants in Black neighborhoods. 8 , 9 Black and Hispanic youth have been especially attractive marketing targets given their higher media use, increased television exposure, and perceived higher influence on mainstream consumerism than other demographic groups. 12 Targeted marking is not inherently problematic. However, multiple reports demonstrate that food and beverage companies disproportionately target unhealthy food advertisements to Black and Hispanic youth, and are less likely to target youth of color with advertisements for healthier food categories. 4 , 8 , 9 These trends have unfortunately only worsened in recent years. 9

Despite overall food and beverage advertising declining by 4% from 2013 to 2017, advertising targeting Black individuals increased by >50%. 4 The disparity between Black and White youth exposure to all food‐related television advertisements has also increased over this period: in 2013, Black teens viewed 70% more food‐related television advertisements than White teens, but by 2017, Black teens viewed 119% more food‐related advertisements. 4 Studies also demonstrate that Black youth watch more television advertisements for fast food, snacks, and candy compared with their White youth peers. 13 Furthermore, a national study linking television ratings data with census information on race found that child/adolescent advertisements for sugary beverages and fast‐food restaurants are significantly more prominent in neighborhoods with Black children/adolescents. 14 In contrast, advertisements for healthier products (100% juice, water, nuts, and fruit), which made up only 3% of all food‐related advertisement expenditures in 2017, were even less likely to be featured on Black‐targeted television, comprising merely 1% of Black‐targeted advertisements.

In contrast to Black‐targeted advertising, total spending for Spanish‐language television advertising targeting Hispanic youth declined by 8% between 2013 and 2017. 4 Despite this, Coca‐Cola and Nestle––which typically advertise foods high in sugar, salt, and calories––more than doubled their Spanish‐language advertising spending during this time. 4 Food companies selling candy, sugary drinks, and snack foods also disproportionately advertised their products on Spanish‐language television, while brands in healthier food categories (100% juice, water, nuts, and fruits) were least represented on Spanish‐language television. 4 Despite the aforementioned 3% allocation of advertisement spending dedicated to healthier options by companies, the advertisements highlighting these options were not present at all on Spanish‐language television advertisments. 4 For this report, we used Spanish‐language television advertisements as a proxy for Hispanic‐targeted television advertising; however, further research investigating the content of non–Spanish‐language television advertisements directed toward Hispanic youth is warranted.

Overall, these collective findings represent a significant public health concern in need of special consideration by the medical community and public health officials, especially when considered in the context of persistent racial health disparities in obesity‐related diseases in our country. 1 , 2

Links Between Food Advertising, Unhealthy Diets, and Chronic Disease Risk in Black and Hispanic Youth

The World Health Organization states that unhealthy food marketing aimed at children and teens is a significant contributor to poor diet quality and diet‐related diseases worldwide. 10 Similarly, the US Institute of Medicine found that food marketing to youth results in increased preferences for nutritionally poor foods, increased requests to parents for unhealthy foods, and increased intake of unhealthy food and beverages. 5 , 6 Multiple reports have also demonstrated a direct link between increased food advertisement viewing and increased childhood adiposity, body mass index, and obesity. 5 , 6 , 7 One study estimating the proportion of childhood obesity attributable to televised food advertisements found that up to one third of obese youth may not have been obese in the absence of these targeted advertisement practices. 15

This is significant, as childhood obesity leads to higher adulthood rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart disease, stroke, cancer, and early mortality. 5 , 10 Unhealthy diets are a key modifiable risk factor for both cardiovascular disease and cancer. 10 While deaths from cardiovascular disease primarily occur in adulthood, unhealthy dietary habits, and the risks associated with them, can begin early in childhood and build throughout life. 10 Indeed, some studies suggest that unhealthy childhood lifestyles may promote the beginning of various deleterious cardiovascular disease processes, including subclinical atherosclerosis, arterial wall stiffening, atherosclerotic plaque formation, insulin resistance, and adverse long‐term heart remodeling. 16 , 17 Therefore, food advertising may play a direct role in promoting obesity and diet‐related diseases in children that continue to have negative health repercussions throughout adulthood.

By promoting poor diet and negative health outcomes in Black and Hispanic youth, vulnerable populations who are disproportionately affected by obesity and obesity‐related diseases, 1 , 2 targeted food advertising may be a powerful independent contributor to racial health disparities in the United States. Regulation of these practices should therefore become a top policy priority in the coming years. Other contributors to underlying racial disparities in obesity include lower education levels, higher levels of food insecurity, greater access to poor quality foods, less access to convenient places for physical activity, and poor access to health care. 1 , 2 Therefore, proposed policy options should ideally address multiple upstream determinants of these racial health disparities.

Opportunities for Policy Action

Several past policy initiatives have attempted to regulate unhealthy food advertising to youth with varying degrees of success. For example, the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI) launched in 2006, in which companies pledged to encourage healthier dietary choices in advertisements to children younger than 12 years. 4 In 2014, this pledge was strengthened when participating food and beverage companies also agreed to only market foods that met uniform nutrition criteria to children. This produced positive changes: from 2013 to 2017, overall food and beverage advertising declined, fruit and vegetable advertisements increased, and children’s meals began offering healthier options. 4 Although this represents positive steps in the right direction, one study showed >86% of the products marketed to children by CFBAI companies remain high in saturated fat, sugar, and sodium. 3 Further action is therefore warranted to achieve the initiative’s ultimate goals. Moreover, no policy to date has specifically addressed the disproportionate advertising of unhealthy foods to Black and Hispanic youth. However, such pro‐equity policy initiatives are critical to combating health disparities. We should thus strive to make health equity impact a central part of policy development, implementation, and evaluation going forward.

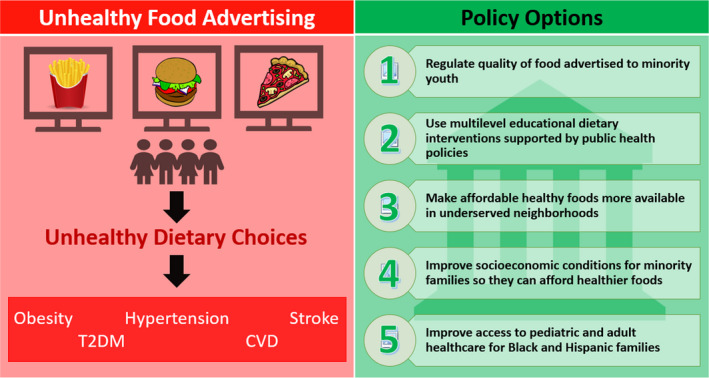

To address these issues, we propose 5 additional policy approaches (Figure). First, we should aim to regulate the proportion and quality of foods targeted toward Black and Hispanic youth. This policy goal could potentially be addressed at the federal, state, and local legislative levels, as well as the private sector. We outline some potential policy options below.

Figure 1. Adverse health effects of targeted ads and policy options to consider.

Targeted food advertisements lead to unhealthy dietary habits, which promote the development of diet‐related disease. Here we list our proposed policy mechanisms to combat the hazardous impact of these practices. CVD indicates cardiovascular disease; and T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

At the federal level, policymakers could consider implementing laws that would deny tax deductions for companies known to target advertisements for foods of poor nutritional quality to Black and Hispanic children. For example, the Stop Subsidizing Childhood Obesity Act, proposed in the House of Representatives in 2016, would have denied a tax deduction to companies marketing foods of poor nutrition quality to all children younger than 14, regardless of race. 18 This legislation ultimately did not pass. 18 However, in the same year, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) required all districts participating in the federal school meals programs to prohibit the marketing of products that did not meet certain nutrition standards on school property during the school day. 18 To take this a step further, federal legislators could also consider banning the sale of these items on school property during the school day altogether. These options have the potential to produce positive changes, as the implementation of food environment policies in schools has previously led to improved dietary changes in youth: increased intake of fruit and vegetables and reduced consumption of sugary beverages and unhealthy snacks. 19

At the state level, policymakers could pass bills requiring all products advertised or sold in vending machines on state‐owned property to meet certain nutritional standards. They could also prohibit schools, especially those in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, from advertising unhealthy food or beverages during the school day. In 2017, the Louisiana governor issued an executive order requiring that all snacks and beverages sold in machines on state‐owned or leased property meet nutrition standards. 18 Several states (Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Texas, and Vermont) introduced similar healthy vending bills in 2016 and 2017. 18

Local policymakers could enact excise taxes on sugary drinks that would limit the manufacturer’s and retailer’s ability to price sugary drinks at an attractively low price, which is a key marketing strategy used to appeal to minority youth. Several municipalities have successfully passed sugary drink taxes to date including Albany, Oakland, and San Francisco, California; Boulder, CO; Philadelphia, PA; and Seattle, WA. 18

More voluntary policy approaches that individual companies, especially the 18 currently participating in the CFBAI, could pursue include pledging to equally distribute advertisements for nutritious foods among Black, Hispanic, and White children. Media companies that own programming with large Black or Hispanic audiences can consider establishing standards for the amount of healthy versus unhealthy foods advertised. They could implement incentives (ie, lowering fees) for those advertising healthier products. Public health advocacy campaigns can also consider publicly supporting companies that advertise nutritious foods to Hispanic and Black youth, and highlight those who disproportionately advertise unhealthy products to Hispanic and Black youth.

Our second policy approach is to promote multilevel educational initiatives targeting environmental factors such as food marketing and media, which have been proven to lead to healthier dietary habits in Black and Hispanic groups. 19 Educational interventions for youth may present a key opportunity to promote healthy dietary habits in childhood and prevent adverse outcomes in adulthood. Researchers have proposed implementing early and maintained multilevel (child, teacher, family, and school) and multifactorial (diet, physical activity, and body and heart awareness) health educational interventions to effectively initiate and sustain healthy childhood behaviors. 19 Studies implementing such initiatives have led to healthier dietary habits in youth from underserved communities and minority racial groups 19 ; therefore, it is critical that public health policies support these efforts moving forward.

Three more fundamental interventions targeting root determinants of disease would include enhancing the availability of affordable healthy food options in communities with high Black and Hispanic populations; improving the socioeconomic conditions of Black and Hispanic communities living in the United States so that they can afford healthier foods; and improving access to pediatric and adult health care, which would increase exposure to healthy lifestyle counseling and facilitate the early detection and management of risk factors. To enhance healthy food access and improve socioeconomic conditions, state policymakers can consider implementing incentive programs that would encourage grocery stores to locate in underserved areas. These programs, which have been established in Pennsylvania, New York, and Illinois, 20 assist grocery stores with the costs associated with land acquisition, building and construction, retail feasibility studies, and other development activities. 20 Such incentives can spur economic development in underserved neighborhoods by inspiring other businesses to invest in the same area, which creates more jobs for local residents and leads to modest increases in the value of nearby homes. Finally, improving access to health care for Hispanic and Black youth could be accomplished by providing additional federal funding to community health centers, which increase primary care access for medically underserved communities.

Conclusions

While many factors contribute to childhood obesity, targeted food advertising likely plays a major role in influencing children’s dietary habits and promoting racial disparities in obesity and obesity‐related diseases. These practices have large implications for population health. Thus, protecting children from unhealthy food marketing and promoting healthy dietary habits for all should be top public health priorities. Although past policy initiatives have been promising, they fall short in achieving these goals. Moving forward, we should aim to prioritize the health of our youth above the needs of corporations. We should strive to regulate the amount and quality of foods targeted not just to our youth but to Black and Hispanic youth, specifically. It is also critical to make healthier foods more affordable to ensure that unhealthy food (ie, fast food) is not the only cost‐efficient option available for Black and Hispanic families. Last, we should adopt an innovative systems‐level approach that uses policy, public health, community, and individual‐level initiatives, to effectively and fundamentally enable healthier food choices and favorably impact population health.

Sources of Funding

Dr Michos is funded by the unrestricted Blumenthal Scholars fund for Preventive Cardiology at Johns Hopkins University.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Miguel Cainzos‐Achirica, Associate Director of Preventive Cardiology at Houston Methodist, for his critical contributions to the article and Figure.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e018900. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018900.)

The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the editors or of the American Heart Association.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 5.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pulgaron ER, Delamater AM. Obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: epidemiology and treatment. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mayer‐Davis EJ, Lawrence JM, Dabelea D, Divers J, Isom S, Dolan L, Imperatore G, Linder B, Marcovina S, Pettitt DJ, et al. Incidence trends of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among youths, 2002–2012. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1419–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Powell LM, Schermbeck RM, Chaloupka FJ. Nutritional content of food and beverage products in television advertisements seen on children’s programming. Child Obes. 2013;9:524–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Harris JL, Frazier W III, Kumanyika S, Ramirez AG, UConnRuddcenter.org. Increasing Disparities in Unhealthy Food Advertising Targeted to Hispanic and Black Youth. 2019. http://uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/TargetedMarketingReport2019.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2019.

- 5. Institute of Medicine . Influence of Marketing on the Diets and Diet‐ Related Health of Children and Youth. In: McGinnis JM, Gootman JA, Kraak VI, eds. Food marketing to children and youth: threat or opportunity? Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: associations with children’s fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Economics and Human Biology. 2011;9:221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lobstein T, Dibb S. Evidence of a possible link between obesogenic food advertising and child overweight. Obes Rev. 2005;6:203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grier SA, Kumanyika SK. The context for choice: Health implications of targeted food and beverage marketing to African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1616–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grier SA, Kumanyika S. Targeted marketing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:349–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization . Evidence. Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non‐Alcoholic Beverages to Children. Geneva, GE: WHO Press; 2010. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44416/9789241500210_eng.pdf;jsessionid=B74416C6F892779CECD24F0AF2C03A85?sequence=1. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nguyen KH, Glantz SA, Palmer CN, Schmidt LA. Transferring racial/ethnic marketing strategies from tobacco to food corporations: Philip Morris and Kraft General Foods. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:329–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bragg MA, Miller AN, Kalkstein DA, Elbel B, Roberto CA. Evaluating the influence of racially targeted food and beverage advertisements on Black and White adolescents’ perceptions and preferences. Appetite. 2019;140:41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fleming‐Milici F, Harris JL. Television food advertising viewed by preschoolers, children and adolescents: contributors to differences in exposure for black and white youth in the United States. Pediatric Obesity. 2018;13:103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Powell LM, Wada R, Kumanyika SK. Racial/ethnic and income disparities in child and adolescent exposure to food and beverage television ads across the U.S. media markets. Heal Place. 2014;29:124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Veerman JL, Van Beeck EF, Barendregt JJ, Mackenbach JP. By how much would limiting TV food advertising reduce childhood obesity? Eur J Public Health. 2009;19:365–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Bao W, Newman WP, Tracy RE, Wattigney WA. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1650–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pahkala K, Hietalampi H, Laitinen TT, Viikari JS, Rönnemaa T, Niinikoski H, Lagström H, Talvia S, Jula A, Heinonen OJ, et al. Ideal cardiovascular health in adolescence: effect of lifestyle intervention and association with vascular intima‐media thickness and elasticity (the Special Turku Coronary Risk Factor Intervention Project for Children [STRIP] study). Circulation. 2013;127:2088–2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mancini S, Harris J. UConnRuddcenter.org. Policy changes to reduce unhealthy food and beverage marketing to children in 2016 and 2017. http://uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/Food%20marketing%20policy%20brief_Final.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2020.

- 19. Fernandez‐Jimenez R, Al‐Kazaz M, Jaslow R, Carvajal I, Fuster V. Children present a window of opportunity for promoting health: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3310–3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chapter 2: Grocery Stores Encouraging Full Service Grocery Stores to Locate in Underserved Areas and Promote Healthier Foods. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.fns.usda.gov/healthy‐incentives‐pilot‐hip‐interim‐report. Accessed September 30, 2020.