Abstract

Background

This study sought to investigate the safety of 3‐month dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in patients receiving ultrathin sirolimus‐eluting stents with biodegradable polymer (Orsiro).

Methods and Results

The SMART‐CHOICE (Smart Angioplasty Research Team: Comparison Between P2Y12 Antagonist Monotherapy vs Dual Anti‐ platelet Therapy in Patients Undergoing Implantation of Coronary Drug‐Eluting Stents) randomized trial compared 3‐month DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy with 12‐month DAPT in 2993 patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. The present analysis was a prespecified subgroup analysis for patients receiving Orsiro stents. As a post hoc analysis, comparisons between Orsiro and everolimus‐eluting stents were also done among patients receiving 3‐month DAPT. Of 972 patients receiving Orsiro stents, 481 patients were randomly assigned to 3‐month DAPT and 491 to 12‐month DAPT. At 12 months, the target vessel failure, defined as a composite of cardiac death, target vessel–related myocardial infarction, or target vessel revascularization, occurred in 8 patients (1.7%) in the 3‐month DAPT group and in 14 patients (2.9%) in the 12‐month DAPT group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; 95% CI, 0.24–1.39; P=0.22). In whole population who were randomly assigned to receive 3‐month DAPT (n=1495), there was no significant difference in the target vessel failure between the Orsiro group and the everolimus‐eluting stent group (n=1014) (1.7% versus 1.8%; HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.41–2.22; P=0.92).

Conclusions

In patients receiving Orsiro stents, clinical outcomes at 1 year were similar between the 3‐month DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy and 12‐month DAPT strategies. With 3‐month DAPT, there was no significant difference in target vessel failure between Orsiro and everolimus‐eluting stents.

Registration

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT02079194.

Keywords: antiplatelet therapy, coronary artery disease, percutaneous coronary intervention

Subject Categories: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Stent, Pharmacology

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- DAPT

dual antiplatelet therapy

- DES

drug‐eluting stent

- EES

everolimus‐eluting stent

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

Orsiro stents are effective and safe for 3‐month dual antiplatelet therapy followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Among patients at high bleeding risk requiring percutaneous coronary intervention, Orsiro stents may be considered in conjunction with a short‐term dual antiplatelet therapy.

Polymer is the key component of drug‐eluting stents (DESs) for facilitation of drug loading and control of drug release. 1 However, durable polymer of the first‐generation DESs has been considered to induce inflammation and to be associated with fatal complications such as late stent thrombosis. 2 To overcome this shortcoming, biodegradable polymer has been applied to the DES system. Early biodegradable polymer DES with thick (120 μm) stainless steel struts demonstrated a reduced risk of very late stent thrombosis compared with the durable polymer sirolimus‐eluting Cypher stent (Cordis/Johnson & Johnson, Warren, NJ) 3 , 4 and comparable efficacy and safety compared with cobalt‐chromium everolimus‐eluting stents. 5 , 6 However, in network meta‐analyses, early biodegradable polymer DESs were associated with a higher risk of definite stent thrombosis than cobalt‐chromium everolimus‐eluting stents, 7 , 8 which might be attributable to thick struts.

The Orsiro stent (Biotronik, Bülach, Switzerland) is a cobalt‐chromium biodegradable polymer sirolimus‐eluting stent. Its thinness may promote strut coverage and passive coating may prevent detrimental interaction between the metal stent and the surrounding tissue. In several head‐to‐head comparisons, Orsiro stents demonstrated comparable 9 or superior 10 , 11 outcomes compared with durable polymer everolimus‐eluting stents (EESs). However, data are limited regarding the safety of short duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after implantation of Orsiro stents. Therefore, this study sought to investigate the safety of 3‐month DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy in patients receiving the Orsiro stents. As a prespecified analysis of the SMART‐CHOICE (Smart Angioplasty Research Team: Comparison Between P2Y12 Antagonist Monotherapy vs Dual Anti‐ platelet Therapy in Patients Undergoing Implantation of Coronary Drug‐Eluting Stents) randomized trial, 12 3‐month DAPT was compared with 12‐month DAPT among patients receiving Orsiro stents. In addition, the outcomes of Orsiro stent were compared with those of EES among whole patients receiving 3‐month DAPT in the SMART‐CHOICE trial.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study Population

The SMART‐CHOICE trial is briefly described in Data S1. Patients were randomly assigned to 3‐month DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy (aspirin plus P2Y12 inhibitor for 3 months and thereafter P2Y12 inhibitor alone) or 12‐month DAPT (aspirin plus P2Y12 inhibitor for at least 12 months). Randomization was performed with a web‐based response system in blocks of 4 and was stratified by clinical presentation (stable ischemic heart disease or acute coronary syndrome), enrolling center, type of P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor), and type of stent used. To minimize the bias from different stent devices, the stents used are limited to cobalt‐chromium everolimus‐eluting Xience stents (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA), platinum‐chromium everolimus eluting Promus/Synergy stents (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA), and sirolimus‐eluting Orsiro stents with biodegradable polymer. For each patient, all lesions had to be treated with the identical type of stent. The SMART‐CHOICE trial was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution, and written consent was obtained from all patients.

Procedures

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was conducted according to standard techniques. Detailed procedures are provided in Data S1. After the index procedure, patients received DAPT with aspirin 100 mg once daily plus clopidogrel 75 mg once daily or prasugrel 10 mg once daily or ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily for 3 months in both groups. The administration of aspirin was stopped at 3 months after the index procedure in the 3‐month DAPT group but was continued in the 12‐month DAPT group. A P2Y12 inhibitor was prescribed continuously in both groups.

Clinical follow‐up was performed at 3, 6, and 12 months after index PCI. At follow‐up, data about patients' clinical status, all interventions received, outcome events, and adverse events were recorded. In particular, information on the use of aspirin or a P2Y12 inhibitor was carefully assessed at each follow‐up.

End Points

The primary end point was the target vessel failure, defined as a composite of cardiac death, target vessel–related myocardial infarction, or target vessel revascularization at 12 months after the index PCI. Secondary end points included the individual component of the primary end point, all‐cause death, any myocardial infarction, repeated revascularization, stent thrombosis, stroke, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium types 2 to 5, and combinations of these end points at 12 months after the index PCI. Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular event was defined as a composite of all‐cause death, myocardial infarction, or stroke; net adverse clinical event, a composite of all‐cause death, any myocardial infarction, stroke, or major bleeding. The definition of each end point is provided in Data S1

Statistical Analysis

The formal power calculation was not done for the present subgroup analyses of the SMART‐CHOICE trial. The primary and secondary end points were primarily analyzed by an intention‐to‐treat principle that included all randomized patients receiving Orsiro stents according to the allocation. Patients who were lost to follow‐up were censored at the time of the last known contact. Cumulative event rates were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method, and Cox regression analysis was performed to compare clinical outcomes between the 3‐month and 12‐month DAPT groups. In addition, post hoc analyses were performed to compare clinical events between Orsiro stents and EESs (Xience and Promus/Synergy) among patients randomly allocated to the 3‐month DAPT. Because stents were not randomized but were chosen by operators, baseline characteristics were adjusted using propensity‐score matching and inverse‐probability weighted analyses. Details regarding statistical analysis are provided in Data S1. All tests were 2‐sided, and a P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) or STATA 16.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

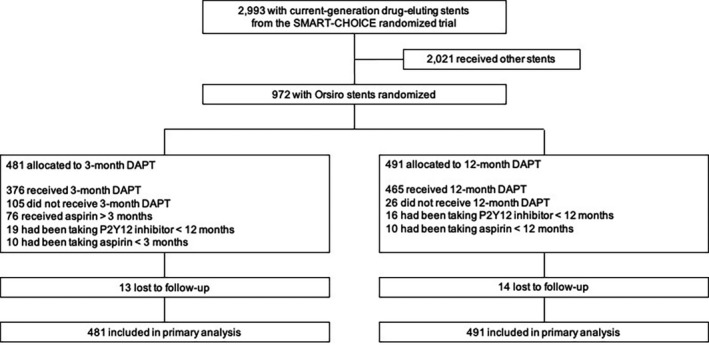

From March 18, 2014, to July 7, 2017, a total of 2993 patients were enrolled. Of these, 972 patients received Orsiro stents; 481 patients were randomly assigned to 3‐month DAPT and 491 to 12‐month DAPT. Figure 1 demonstrates participants' flow in the present study. Table 1 represents baseline clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics according to the intention‐to‐treat analysis in patients receiving Orsiro stents. Although there was no significant difference between the 3‐month and 12‐month DAPT groups, the mean stent length tended to be longer in the 3‐month DAPT group than in the 12‐month DAPT group (38.5±22.8 mm versus 35.9±21.1 mm; P=0.07). The median duration of aspirin was 96 days (interquartile range, 87–121 days) in the 3‐month DAPT group and 365 days (interquartile range, 363–365 days) in the 12‐month DAPT group. The proportion of patients receiving aspirin beyond 3 months in the 3‐month DAPT group was 15.8% (76/481) at 6 months and 10.8% (52/481) at 12 months. Clopidogrel was used as the P2Y12 inhibitor in 82.5% (802/972) in the entire patients: 82.1% (395/481) in the 3‐month DAPT group and 82.9% (407/491) in the 12‐month DAPT group. Prasugrel or ticagrelor, potent P2Y12 inhibitors, were used in 17.5% (170/972) in the entire patients: 17.9% (86/481) in the 3‐month DAPT group and 17.1% (84/491) in the 12‐month DAPT group.

Figure 1. Participants' flow.

DAPT indicates dual antiplatelet therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Dual Antiplatelet Therapy | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 mo (n=481) | 12 mo (n=491) | ||

| Age, y | 65.1±10.7 | 65.3±10.3 | 0.71 |

| Male | 347 (72.1) | 360 (73.3) | 0.68 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 194 (40.3) | 190 (38.7) | 0.60 |

| Hypertension | 294 (61.1) | 314 (64.0) | 0.36 |

| Dyslipidemia | 211 (43.9) | 218 (44.4) | 0.87 |

| Current smoking | 121 (25.2) | 116 (23.6) | 0.58 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 26 (5.4) | 25 (5.1) | 0.83 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 6 (1.3) | 5 (1.0) | 0.74 |

| Previous revascularization | 58 (12.1) | 67 (13.7) | 0.46 |

| Chronic renal failure | 15 (3.1) | 16 (3.3) | 0.90 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 60.0±10.6 | 59.8±11.1 | 0.80 |

| Clinical presentation | 0.38 | ||

| Stable angina | 227 (47.2) | 229 (46.6) | |

| Unstable angina | 126 (26.2) | 150 (30.6) | |

| Non–ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction | 86 (17.9) | 76 (15.5) | |

| ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction | 42 (8.7) | 36 (7.3) | |

| Multiple‐vessel disease | 233 (48.4) | 233 (47.5) | 0.76 |

| Location of lesion treated | |||

| Left main | 5 (1.0) | 8 (1.6) | 0.42 |

| Left anterior descending artery | 295 (61.3) | 295 (60.1) | 0.69 |

| Left circumflex | 128 (26.6) | 129 (26.3) | 0.90 |

| Right coronary artery | 176 (36.6) | 171 (34.8) | 0.57 |

| Lesion complexity | |||

| Calcified lesion | 89 (18.5) | 90 (18.3) | 0.94 |

| Bifurcation lesion | 60 (12.5) | 61 (12.4) | 0.98 |

| Thrombotic lesion | 34 (7.1) | 33 (6.7) | 0.83 |

| Use of intravascular ultrasound | 91 (18.9) | 110 (22.4) | 0.18 |

| Treated lesions per patient | 1.4±0.7 | 1.3±0.6 | 0.14 |

| Multilesion intervention | 150 (31.2) | 143 (29.1) | 0.48 |

| Multivessel intervention | 114 (23.7) | 111 (22.6) | 0.69 |

| Number of stents per patient | 1.5±0.8 | 1.4±0.7 | 0.12 |

| Mean stent diameter per patient, mm | 3.0±0.4 | 3.0±0.4 | 0.91 |

| Total stent length per patient, mm | 38.5±22.8 | 35.9±21.1 | 0.07 |

Data are n (%) or means±SD.

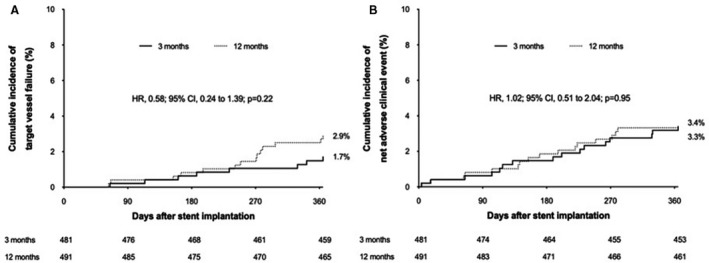

Follow‐up for the primary end point was complete for 945 patients (97.2%) in patients receiving Orsiro stents. Table 2 demonstrates clinical outcomes at 12 months. In the intention‐to‐treat analysis, the primary end point occurred in 8 patients in the 3‐month DAPT group and 14 in the 12‐month DAPT group. The cumulative rates of primary end point were 1.7% in the 3‐month DAPT group and 2.9% in the 12‐month DAPT group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; 95% CI, 0.24–1.39; P=0.22) (Figure 2A). Also, the cumulative rates of the net adverse clinical event did not differ between the 3‐ and 12‐month DAPT groups (3.4% versus 3.3%; HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.51–2.04; P=0.95) (Figure 2B). Stent thrombosis did not occur in both groups. The landmark analyses showed that the risks of primary end point (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.23–1.51; P=0.27) and net adverse clinical event (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.51–2.43; P=0.80) were not significantly different between the 3‐ and 12‐month DAPT groups (Figure S1). In per‐protocol analysis, results were consistent with those from the intention‐to‐treat analysis (Tables S1 and S2). The treatment effects of 3‐month DAPT compared with 12‐month DAPT were consistent across various subgroups for the primary end point (Figure S2).

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes at 12 months

| Dual Antiplatelet Therapy | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 mo (n=481) | 12 mo (n=491) | |||

| Target vessel failure | 8 (1.7) | 14 (2.9) | 0.58 (0.24–1.39) | 0.22 |

| Cardiac death | 2 (0.4) | 5 (1.1) | 0.41 (0.08–2.10) | 0.28 |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.8) | 0.26 (0.03–2.28) | 0.22 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 6 (1.4) | 8 (1.8) | 0.76 (0.26–2.19) | 0.61 |

| All‐cause death | 5 (1.1) | 6 (1.3) | 0.85 (0.26–2.78) | 0.79 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 2 (0.4) | 8 (1.7) | 0.25 (0.05–1.20) | 0.08 |

| Repeated revascularization | 11 (2.4) | 12 (2.6) | 0.93 (0.41–2.11) | 0.86 |

| Stent thrombosis | 0 | 0 | … | … |

| Stroke | 6 (1.3) | 3 (0.4) | 2.05 (0.51–8.18) | 0.31 |

| Bleeding BARC types 2–5 | 13 (2.8) | 19 (4.0) | 0.69 (0.34–1.40) | 0.30 |

| Major bleeding | 7 (1.5) | 5 (1.0) | 1.43 (0.46–4.51) | 0.54 |

| Major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events | 13 (2.8) | 14 (2.9) | 0.95 (0.45–2.02) | 0.89 |

| Net adverse clinical events | 16 (3.4) | 16 (3.3) | 1.02 (0.51–2.04) | 0.95 |

Data are n or n (%). The percentages are Kaplan–Meier estimates. BARC indicates Bleeding Academic Research Consortium.

Figure 2. Time‐to‐event curves for target vessel failure (A) and net adverse clinical event (B) between 3‐month (line) and 12‐month (dotted line) dual antiplatelet therapy.

HR indicates hazard ratio.

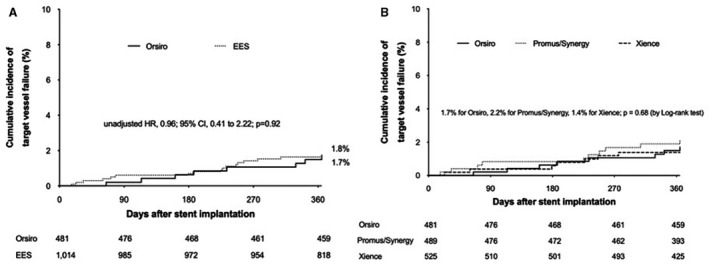

Among 1495 patients allocated to the 3‐month DAPT in the SAMRT‐CHOICE trial, 1014 patients were treated with EESs (457 Promus/32 Synergy and 525 Xience). Baseline characteristics between Orsiro stents and EESs in patients with 3‐month DAPT are presented in Table S3. The intravascular ultrasound during PCI was less frequently used in Orsiro stent than in EES (18.9% versus 27.7%; P=0.0002). The median duration of aspirin was 97 days (interquartile range, 88–117 days) in the EES group and clopidogrel as the P2Y12 inhibitor was used in 74.4% (754/1014) of patients with EESs. Table 3 shows clinical outcomes at 12 months between stent types. The cumulative rates of primary end point were 1.7% in Orsiro stent and 1.8% in EES (unadjusted HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.41–2.22; P=0.92) (Figure 3A). Differences in baseline characteristics were balanced after propensity‐score matching (Table S4), and standardized mean differences after adjustments with propensity‐score matching and inverse‐probability weight were within 0.1 across all matched covariates (Table S5). The comparable effects of Orsiro stent compared with EES were consistent after these adjustments (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical Outcomes at 12 Months in Patients Assigned to 3‐Month Dual Antiplatelet Therapy, Grouped by Stent Types

| Stent Types | Unadjusted | Propensity‐Score Matching | Inverse‐Probability Weighted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orsiro (n=481) | EES (n=1014) | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | HR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Target vessel failure | 8 (1.7) | 17 (1.8) | 0.96 (0.41–2.22) | 0.92 | 0.80 (0.31–2.04) | 0.64 | 0.92 (0.40–2.15) | 0.85 |

| Cardiac death | 2 (0.4) | 9 (0.9) | 0.46 (0.10–2.13) | 0.32 | 0.40 (0.08–2.06) | 0.27 | 0.36 (0.08–1.66) | 0.19 |

| Target vessel–related myocardial infarction | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | 0.69 (0.07–6.66) | 0.75 | 0.33 (0.03–3.20) | 0.34 | 0.67 (0.07–6.39) | 0.73 |

| Target vessel revascularization | 6 (1.4) | 6 (0.6) | 2.08 (0.67–6.43) | 0.21 | 2.01 (0.50–8.09) | 0.33 | 2.10 (0.67–6.58) | 0.20 |

| All‐cause death | 5 (1.1) | 16 (1.6) | 0.65 (0.24–1.78) | 0.40 | 0.62 (0.20–1.91) | 0.41 | 0.52 (0.19–1.40) | 0.19 |

| Any myocardial infarction | 2 (0.4) | 9 (0.9) | 0.46 (0.10–2.13) | 0.32 | 0.25 (0.05–1.17) | 0.08 | 0.54 (0.12–2.54) | 0.44 |

| Repeated revascularization | 11 (2.4) | 13 (1.4) | 1.76 (0.79–3.93) | 0.17 | 1.58 (0.61–4.12) | 0.35 | 1.71 (0.77–3.82) | 0.19 |

| Stent thrombosis | 0 | 3 (0.3) | … | … | … | … | … | … |

Data are n or n (%). The percentages are Kaplan–Meier estimates. EES indicates everolimus‐eluting stent; and HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 3. Time‐to‐event curves for target vessel failure between Orsiro stents (line) and everolimus‐eluting stents (EES; dotted lines).

HR indicates hazard ratio. (A), Orsiro versus EES; (B), Orsiro versus Promus/Synergy versus Xience.

Discussion

In this analysis from the SMART‐CHOICE randomized trial, the 1‐year clinical outcomes in patients undergoing Orsiro stent implantation were similar between the 3‐month DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy and the 12‐month DAPT strategies. The results of landmark and per‐protocol analyses were similar to those from the intention‐to‐treat analysis. The treatment effects of 3‐month DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy for the target vessel failure were consistent among various subgroups. Among whole patients receiving 3‐month DAPT, the incidences of adverse cardiac events were not different between Orsiro stents and EESs for 1‐year follow‐up.

Bleeding after PCI was significantly associated with mortality during follow‐up. Moreover, of patients undergoing PCI, the proportion of patients with high bleeding risk is increasing. Therefore, shortening of DAPT duration or avoidance of unnecessary prolonged DAPT is of paramount importance. The LEADERS FREE (Prospective Randomized Comparison of the BioFreedom Biolimus A9 Drug‐Coated Stent Versus the Gazelle Bare‐Metal Stent in Patients at High Bleeding Risk) trial first revealed that polymer‐free umirolimus‐coated stents followed by 1‐month DAPT reduced major adverse cardiac events compared with bare‐metal stents. 13 Although Orsiro stents showed excellent outcomes in several randomized trials with conventional duration of DAPT, 9 , 10 , 11 it was also reported to be associated with increased risk of stent thrombosis and all‐cause mortality compared with the current‐generation DESs in recent studies. 14 , 15 Therefore, we compared 3‐month DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy with 12‐month DAPT among patients receiving Orsiro stents.

The STOPDAPT‐2 (Short and Optimal Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Everolimus‐Eluting Cobalt‐Chromium Stent) trial enrolling 3045 patients who underwent everolimus‐eluting Xience stent implantation demonstrated that 1 month of DAPT followed by clopidogrel monotherapy, compared with the 12‐month DAPT, resulted in a significantly lower rate of cardiovascular and bleeding events at 1‐year follow‐up. 16 Recently, the Onyx ONE (Resolute Onyx in One Month Dual Antiplatelet Therapy for High‐Bleeding Risk Patients) trial showed that Resolute Onyx DES implantation was noninferior to BioFreedom drug‐coated stent, both with 1‐month DAPT among patients undergoing PCI and with high bleeding risk. 17 Given that the performances of current‐generation DESs are excellent and comparable to each other, extrapolation of the results of these trials to other DESs may be possible. However, we believe that it is desirable and prudent to demonstrate the safety of short‐duration DAPT in each stent. The results of the present study support that the short duration of DAPT may be feasible and safe in patients receiving Orsiro stents like other current‐generation DESs.

In the present analysis, the safety of short‐term DAPT in patients receiving Orsiro stents is obviously based on remarkable advances of technology. The Orsiro stent had hybrid coating that consists of the combination of active (BIOlute) and passive coatings (PROBIO). 18 The BIOlute active coating consists of a biodegradable poly‐L‐lactic acid polymer that elutes sirolimus in which 50% of the drug is released within 30 days and 80% within 3 months (complete degradation of coating within 1–2 years). 19 The PROBIO passive coating encapsulates the metal stent and minimizes interaction between metal and surrounding tissue at sites of contact. 18 The configuration of the coating is asymmetrical and thicker on the abluminal side than on the luminal side (7.4 versus 3.5 μm, respectively), which results in a higher drug dose on the abluminal side of the DES. 20 The Orsiro stent is based on the cobalt‐chromium stent platform with a strut thickness of 60 μm in stents with a nominal diameter ≤3.0 mm and 80 μm in stents with a nominal diameter >3.0 mm. 18 Notably, covered struts per lesion assessed by optical coherence tomography were 90% at 3 months after Orsiro stent implantation. 21 Although the strut coverage identified by optical coherence tomography does not exactly represent the reendothelization of coronary stent, nearly covered stent struts potentially enable the 3‐month DAPT in patients receiving Orsiro stents.

The present study has several limitations. First, the sample size is inadequate for definite conclusion. Second, the included patients were generally at a low risk of ischemia and bleeding. Specifically, mean age was about 65 years old, and the sample of patients with acute coronary syndrome was low. Thus, the present results may not be generalized into elderly patients or patients with acute coronary syndrome and should be interpreted cautiously. Third, there is a possibility of biases caused by low adherence and treatment crossover, especially in the 3‐month DAPT group. However, intention‐to‐treat and per‐protocol analyses showed similar results, suggesting that these potential biases are likely small. Fourth, aspirin is usually recommended as mono antiplatelet therapy following DAPT. 22 However, the TWILIGHT (Ticagrelor With Aspirin or Alone in High‐Risk Patients After Coronary Intervention) trial recently demonstrated that the P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy after 3 months of DAPT among high‐risk patients undergoing PCI was effective and safe. 23 Fifth, type of stents used was not randomized but was determined by operators in the SMART‐CHOICE trial. Unmeasured confounders might affect the clinical outcomes according to stent types, although multiple sensitivity analyses, including propensity‐score matching and inverse‐probability weighting, were performed to adjust baseline differences. Finally, despite the interactions between P2Y12 inhibitors and gastrointestinal medications, especially proton pump inhibitors, related data were not available.

In conclusion, the 3‐month DAPT followed by P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy was as safe as the 12‐month DAPT after Orsiro stent implantation for target vessel failure at 1 year.

Appendix

The SMART‐CHOICE Investigators

Hyeon‐Cheol Gwon, Joo‐Yong Hahn, Young Bin Song, Taek Kyu Park, Joo Myung Lee, Jeong Hoon Yang, Jin‐Ho Choi, Sang Hoon Lee (Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea); Dong‐Bin Kim (Catholic University St. Paul's Hospital, Seoul, Korea); Byung Ryul Cho (Kangwon National University Hospital, Chuncheon, Korea); Woong Gil Choi (Konkuk University Chungju Hospital, Chungju, Korea); Hyuck Jun Yoon (Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center, Daegu, Korea); Seung‐Woon Rha (Korea University Guro Hospital, Seoul, Korea); Deok‐Kyu Cho (Yongin Severance Hospital, Yongin, Korea); Seung Uk Lee (Kwangju Christian Hospital, Gwangju, Korea); Sang Cheol Cho, Sun‐Ho Hwang (Gwangju Veterans Hospital, Gwangju, Korea); Dong Woon Jeon (National Health Insurance Service Ilsan Hospital, Goyang, Korea); Jae Woong Choi (Eulji General Hospital, Seoul, Korea); Jae Kean Ryu (Daegu Catholic University Medical Center, Daegu, Korea); Eul‐Soon Im (Dongsuwon General Hospital, Suwon, Korea); Moo‐Hyun Kim (Dong‐A University Hospital, Busan, Korea); In‐Ho Chae (Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea); Ju‐Hyeon Oh, Woo Jung Chun, Yong Hwan Park, Woo Jin Jang (Samsung Changwon Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Changwon, Korea); Sang‐Hyun Kim, Hack‐Lyoung Kim (Seoul National University Boramae Medical Center, Seoul, Korea); Jang Hyun Cho (St Carollo Hospital, Suncheon, Korea); Dong Kyu Jin (Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital, Cheonan, Korea); Il Woo Suh (SAM Medical Center, Anyang, Korea); Jong Seon Park (Yeungnam University Hospital, Daegu, Korea); Eun‐Seok Shin, Shin‐Jae Kim (Ulsan University Hospital, Ulsan, Korea); Sang‐Sig Cheong (Gangneung Asan Hospital, Gangneung, Korea); Seok Kyu Oh, Kyeong Ho (Wonkwang University Hospital, Iksan, Korea); Sung Yun Lee (Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital, Goyang, Korea); Jong‐Young Lee (Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea); Jei Keon Chae (Chonbuk National University Hospital, Jeonju, Korea); Young Youp Koh (Chosun University Hospital, Gwangju, Korea); Wang Soo Lee (Chung‐Ang University Hospital, Seoul, Korea); Yong Mo Yang (Cheongju Saint Mary's Hospital, Cheongju, Korea); Jin‐Ok Jeong (Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, Korea); Jang‐Whan Bae (Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju, Korea); and Joon‐Hyouk Choi (Jeju National University Hospital, Jeju, Korea).

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the Korean Society of Interventional Cardiology, Abbott Vascular Korea, Biotronik Korea, and Boston Scientific Korea. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures

Dr Hahn has received grants from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Daiichi Sankyo, and Medtronic; and speaker's fees from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, and Sanofi‐Aventis. Dr Gwon has received research grants from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic; and speaker's fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e018366. DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018366.)

Supplementary Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.120.018366

Contributor Information

Byung Ryul Cho, Email: heartcho@kangwon.ac.kr.

Joo‐Yong Hahn, Email: jyhahn@skku.edu.

SMART‐CHOICE Investigators:

Dong‐Bin Kim, Sang Cheol Cho, Sun‐Ho Hwang, Dong Woon Jeon, Jae Kean Ryu, Moo‐Hyun Kim, In‐Ho Chae, Sang‐Hyun Kim, Hack‐Lyoung Kim, Dong Kyu Jin, Il Woo Suh, Jong Seon Park, Eun‐Seok Shin, Shin‐Jae Kim, Sang‐Sig Cheong, Kyeong Ho, Sung Yun Lee, Jong‐Young Lee, Jei Keon Chae, Yong Mo Yang, Jin‐Ok Jeong, Jang‐Whan Bae, and Joon‐Hyouk Choi

References

- 1. Rizas KD, Mehilli J. Stent polymers: do they make a difference? Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e002943. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.002943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Virmani R, Guagliumi G, Farb A, Musumeci G, Grieco N, Motta T, Mihalcsik L, Tespili M, Valsecchi O, Kolodgie FD. Localized hypersensitivity and late coronary thrombosis secondary to a sirolimus‐eluting stent: should we be cautious? Circulation. 2004;109:701–705. DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000116202.41966.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Windecker S, Serruys PW, Wandel S, Buszman P, Trznadel S, Linke A, Lenk K, Ischinger T, Klauss V, Eberli F, et al. Biolimus‐eluting stent with biodegradable polymer versus sirolimus‐eluting stent with durable polymer for coronary revascularisation (LEADERS): a randomised non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1163–1173. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stefanini GG, Kalesan B, Serruys PW, Heg D, Buszman P, Linke A, Ischinger T, Klauss V, Eberli F, Wijns W, et al. Long‐term clinical outcomes of biodegradable polymer biolimus‐eluting stents versus durable polymer sirolimus‐eluting stents in patients with coronary artery disease (LEADERS): 4 year follow‐up of a randomised non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2011;378:1940–1948. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61672-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smits PC, Hofma S, Togni M, Vázquez N, Valdés M, Voudris V, Slagboom T, Goy J‐J, Vuillomenet A, Serra A, et al. Abluminal biodegradable polymer biolimus‐eluting stent versus durable polymer everolimus‐eluting stent (COMPARE II): a randomised, controlled, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381:651–660. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61852-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Natsuaki M, Kozuma K, Morimoto T, Kadota K, Muramatsu T, Nakagawa Y, Akasaka T, Igarashi K, Tanabe K, Morino Y, et al. Biodegradable polymer biolimus‐eluting stent versus durable polymer everolimus‐eluting stent: a randomized, controlled, noninferiority trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:181–190. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Palmerini T, Biondi‐Zoccai G, Della Riva D, Mariani A, Sabaté M, Smits PC, Kaiser C, D'Ascenzo F, Frati G, Mancone M, et al. Clinical outcomes with bioabsorbable polymer‐ versus durable polymer‐based drug‐eluting and bare‐metal stents: evidence from a comprehensive network meta‐analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:299–307. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kang S‐H, Park KW, Kang D‐Y, Lim W‐H, Park KT, Han J‐K, Kang H‐J, Koo B‐K, Oh B‐H, Park Y‐B, et al. Biodegradable‐polymer drug‐eluting stents vs. bare metal stents vs. durable‐polymer drug‐eluting stents: a systematic review and Bayesian approach network meta‐analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1147–1158. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pilgrim T, Heg D, Roffi M, Tüller D, Muller O, Vuilliomenet A, Cook S, Weilenmann D, Kaiser C, Jamshidi P, et al. Ultrathin strut biodegradable polymer sirolimus‐eluting stent versus durable polymer everolimus‐eluting stent for percutaneous coronary revascularisation (BIOSCIENCE): a randomised, single‐blind, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2014;384:2111–2122. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kandzari DE, Mauri L, Koolen JJ, Massaro JM, Doros G, Garcia‐Garcia HM, Bennett J, Roguin A, Gharib EG, Cutlip DE, et al. Ultrathin, bioresorbable polymer sirolimus‐eluting stents versus thin, durable polymer everolimus‐eluting stents in patients undergoing coronary revascularisation (BIOFLOW V): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1843–1852. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kandzari DE, Koolen JJ, Doros G, Massaro JJ, Garcia‐Garcia HM, Bennett J, Roguin A, Gharib EG, Cutlip DE, Waksman R. Ultrathin bioresorbable polymer sirolimus‐eluting stents versus thin durable polymer everolimus‐eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3287–3297. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hahn J‐Y, Song YB, Oh J‐H, Chun WJ, Park YH, Jang WJ, Im E‐S, Jeong J‐O, Cho BR, Oh SK, et al. Effect of P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy vs dual antiplatelet therapy on cardiovascular events in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the SMART‐CHOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:2428–2437. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.8146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Urban P, Meredith IT, Abizaid A, Pocock SJ, Carrié D, Naber C, Lipiecki J, Richardt G, Iñiguez A, Brunel P, et al. Polymer‐free drug‐coated coronary stents in patients at high bleeding risk. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2038–2047. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pilgrim T, Piccolo R, Heg D, Roffi M, Tüller D, Muller O, Moarof I, Siontis GCM, Cook S, Weilenmann D, et al. Ultrathin‐strut, biodegradable‐polymer, sirolimus‐eluting stents versus thin‐strut, durable‐polymer, everolimus‐eluting stents for percutaneous coronary revascularisation: 5‐year outcomes of the BIOSCIENCE randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;392:737–746. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31715-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. von Birgelen C, Zocca P, Buiten RA, Jessurun GAJ, Schotborgh CE, Roguin A, Danse PW, Benit E, Aminian A, van Houwelingen KG, et al. Thin composite wire strut, durable polymer‐coated (Resolute Onyx) versus ultrathin cobalt‐chromium strut, bioresorbable polymer‐coated (Orsiro) drug‐eluting stents in allcomers with coronary artery disease (BIONYX): an international, single‐blind, randomised non‐inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;392:1235–1245. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Watanabe H, Domei T, Morimoto T, Natsuaki M, Shiomi H, Toyota T, Ohya M, Suwa S, Takagi K, Nanasato M, et al. Effect of 1‐month dual antiplatelet therapy followed by clopidogrel vs 12‐month dual antiplatelet therapy on cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients receiving PCI: the STOPDAPT‐2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:2414–2427. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2019.8145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Windecker S, Latib A, Kedhi E, Kirtane AJ, Kandzari DE, Mehran R, Price MJ, Abizaid A, Simon DI, Worthley SG, et al. Polymer‐based or polymer‐free stents in patients at high bleeding risk. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1208–1218. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lam MK, Sen H, Tandjung K, van Houwelingen KG, de Vries AG, Danse PW, Schotborgh CE, Scholte M, Löwik MM, Linssen GCM, et al. Comparison of 3 biodegradable polymer and durable polymer‐based drug‐eluting stents in all‐comers (BIO‐RESORT): rationale and study design of the randomized TWENTE III multicenter trial. Am Heart J. 2014;167:445–451. DOI: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tittelbach M, Diener T. Orsiro—the first hybrid drug‐eluting stent, opening up a new class of drug‐eluting stents for superior patient outcomes. Interv Cardiol. 2011;6:142–144. DOI: 10.15420/icr.2011.6.2.142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koppara T, Joner M, Bayer G, Steigerwald K, Diener T, Wittchow E. Histopathological comparison of biodegradable polymer and permanent polymer based sirolimus eluting stents in a porcine model of coronary stent implantation. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:1161–1171. DOI: 10.1160/TH12-01-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kretov Е, Naryshkin I, Baystrukov V, Grazhdankin I, Prokhorikhin A, Zubarev D, Biryukov A, Verin V, Boykov A, Malaev D, et al. Three‐months optical coherence tomography analysis of a biodegradable polymer, sirolimus‐eluting stent. J Interv Cardiol. 2018;31:442–449. DOI: 10.1111/joic.12510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neumann F‐J, Sousa‐Uva M, Ahlsson A, Alfonso F, Banning AP, Benedetto U, Byrne RA, Collet J‐P, Falk V, Head SJ, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87–165. DOI: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mehran R, Baber U, Sharma SK, Cohen DJ, Angiolillo DJ, Briguori C, Cha JY, Collier T, Dangas G, Dudek D, et al. Ticagrelor with or without aspirin in high‐risk patients after PCI. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2032–2042. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, Gabriel Steg P, Morel MA, Mauri L, Vranckx P, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, Gibson CM, Caixeta A, Eikelboom J, Kaul S, Wiviott SD, Menon V, Nikolsky E, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.