To the Editor: The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted many aspects of undergraduate medical education, including clinical rotations and United States medical licensing examinations.1 The coalition for physician accountability has recommended the suspension of away (ie, visiting or external) rotations for the 2020-2021 residency application cycle, with exceptions of students without a home residency program and students needing them for graduation or accreditation requirements.2 Away rotations, completed at a medical school outside of their institution, are key for students applying to the field of dermatology for expanding opportunities for advanced clinical experiences, individualized mentorship, and an insight into resident life.3 Programs also benefit from evaluating candidates’ “fit” for their residency over an “audition” period. The visiting rotation freeze complicated this application cycle for both stakeholders but provided an opportunity to address the historical inaccessibility of away rotations for many.4 , 5

To tackle this limitation in hosting external students, our program organized a 4-week virtual visiting rotation allowing students to interact remotely with residents and faculty. Through videoconferencing platforms, learners actively participated in various academic activities, such as journal club, clinicopathologic conference, grand rounds, and resident didactics. Virtual “happy hours” and faculty mentoring sessions allowed for more personalized engagement. At the conclusion of the virtual rotations, the students were surveyed to evaluate their experience.

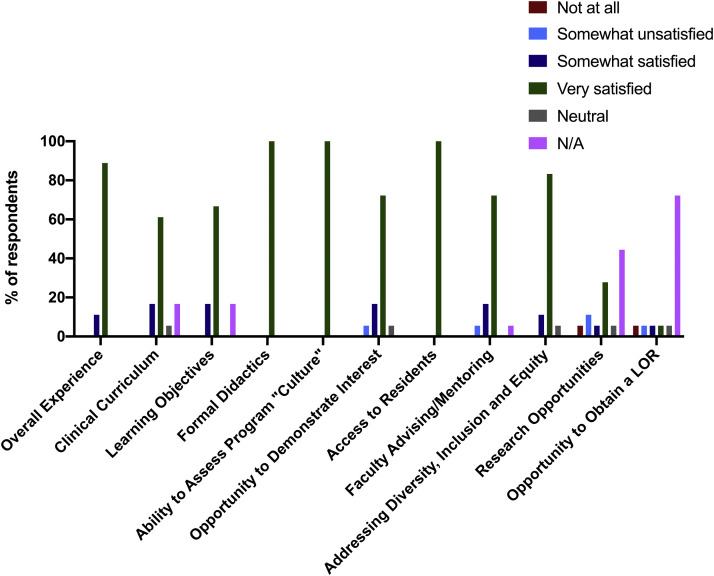

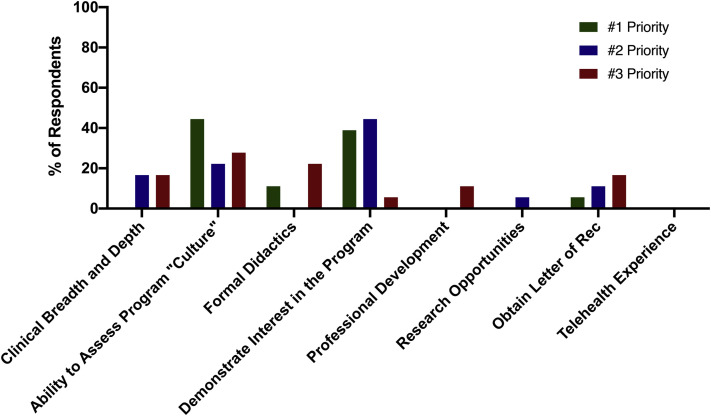

The participants were asked about their priorities for an away rotation and the opportunity to meet those expectations, level of satisfaction on various facets of our offering, and whether they would have had the opportunity to visit our program if in-person away rotations were not canceled. With an overall response rate of 75% (n = 18), majority of the rotators reported “very satisfied” with the clinical curriculum, learning objectives, formal didactics, ability to assess program culture, opportunity to demonstrate interest, access to the residents, faculty advising, and diversity and inclusion initiatives (61%, 67%, 100%, 100%, 72%, 100%, 72%, and 83%, respectively; Fig 1 ). They viewed research opportunities and obtaining letters of recommendation as “not applicable” (Fig 1), but these aspects were also not the highest priorities reported (Fig 2 ). The students acknowledged that they received ample opportunity to meet their priorities for an away rotation (78%; Supplemental Fig 1, A, available via Mendeley at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/6d9zg7m4h9/2), and 39% noted that they might not have had the traditional advantage to rotate with this program (Supplemental Fig 1, B).

Fig 1.

Self-reported level of satisfaction with various features of the virtual visiting program.

Fig 2.

Self-reported priorities for an away rotation.

The nationwide discussion of adapting medical education and our sampling of applicant perspectives reflect the need for further data-driven exploration of virtual away rotations. The intrinsic selection and acquiescence biases in polling students interested in this specific program were addressed with informed consent emphasizing anonymity and no effect on evaluations, and recall bias was minimized by survey completion on a rolling basis immediately after a student's rotation ended. Academic faculty's views were not examined. Despite these limitations, our findings illustrated that the priorities of away rotations can be met through a virtual model and that remote alternatives can capture candidates unable to leverage a physical clinical rotation. Investing resources to establish or improve virtual visiting electives will not only mitigate challenges in this application cycle but also catalyze changes that address financial and scheduling inequities inherent to the traditional away rotation system.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding Sources: None.

IRB approval status: Designated as exempt (NCR203119).

References

- 1.Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2131–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coalition for Physician Accountability Final report and recommendations for medical education institutions of LCME-accredited, US osteopathic, and non-US medical school applicants. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-05/covid19_Final_Recommendations_05112020.pdf Available at:

- 3.Cao S.Z., Nambudiri V.E. A national cross-sectional analysis of dermatology away rotations using the visiting student application service database. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23(12):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffith M., DeMasi S.C., McGrath A.J., Love J.N., Moll J., Santen S.A. Time to reevaluate the away rotation: improving return on investment for students and schools. Acad Med. 2019;94(4):496–500. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winterton M., Ahn J., Bernstein J. The prevalence and cost of medical student visiting rotations. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0805-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]