Acute asthma exacerbations (AEs) are common events that result in high morbidity and mortality and place a major burden on health care services. The most prominent trigger for AEs is viral respiratory infections, particularly rhinoviruses (RVs), which have been strongly linked as causative agents by studies of naturally occurring and experimentally induced exacerbations.1 , 2 RVs induce enhanced airway inflammation and clinical symptom severity in patients with asthma compared with healthy individuals.1 Impaired innate antiviral immunity and augmented TH2 inflammation in people with asthma are 2 potential mechanisms linked to increased severity of virus-induced AE pathogenesis. Here, we review the role played by viruses in AEs and the role of asthma in the risk of severe outcomes in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Interferon impairment in people with asthma

Interferons (IFNs) are critical components of innate immune response and are a robust first line of defense against viruses. IFNs protect cells from viral pathogens through induction of IFN-stimulated-genes, which have pleotropic antiviral effects. There are 3 classes of IFNs: types I (IFN-α and IFN-β), II (IFN-γ), and III (IFN-λ).

Numerous studies have demonstrated that IFN induction by viruses is delayed and impaired in people with asthma. Ex vivo studies in cells from people with asthma showed delay and impairment in production of IFN-α, IFN-β, IFN-γ, and IFN-λ in bronchoalveolar lavage cells, PBMCs, dendritic cells (DCs), and human bronchial epithelial cells (HBECs) in response to infection with RVs and other respiratory viruses.3

The importance of IFN impairment in AE pathogenesis is strongly supported by a study showing that IFN impairment at baseline is strongly related to symptom severity, airway inflammation, and viral load in subsequent experimental virus-induced AEs.3

An elegant study applying transcriptome network analysis, in children with asthma, also demonstrated that a low type-1 IFN response at baseline was a robust predictor of short-term AE risk.1 The same study reported a “type-1 IFN response” module, which contained numerous antiviral effector molecules, was upregulated in nasal and blood samples during virus-induced AEs, and suggested that low IFN signaling at baseline enhances viral replication during early infection, which secondarily induces an exaggerated IFN response later during exacerbation.1 This interpretation is supported by a study reporting an approximately 250-fold increase in nasal lavage virus load in people with asthma compared with healthy subjects, on day 3 following RV experimental infection2 followed by subsequent increased nasal mucosal lining fluid levels of IFN-γ and the IFN-stimulated-genes CXCL11/ITAC, CXCL10/IP10, and IL-15, at later time points.4

Clinical trials of inhaled IFN-β have shown attenuation of cold-induced worsening of peak flow and of asthma symptoms5 in people with moderate/severe asthma, but neither study was large enough to include AE frequency as an outcome. Further studies are required if this treatment is to progress as a potential AE therapy.

Role of type 2 cytokines in virus-induced AEs

Asthma can be subdivided into 2 major endotypes: type-2–high and non–type-2. Atopic or allergic asthma involves allergen-specific TH2 cells producing IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, the prototypical type-2 cytokines that co-ordinate to induce eosinophilic airway inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, airway remodeling, and allergen-specific IgE production, the hallmark pathological features of atopic asthma.

An in vivo study in RV-challenged nonallergic healthy control subjects and subjects with allergic asthma demonstrated virus induction of the epithelial alarmin IL-33, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and airway eosinophils only in the subjects with asthma.2 During the RV infection, IL-5 and IL-13 levels in the subjects with asthma were correlated with AE severity, suggesting that type-2 cytokines may play a causal role in driving clinical exacerbation severity. This is supported by clinical trials showing that blocking IL-5 or IL-4/IL-13 reduces exacerbation frequency very substantially. Furthermore, RV infection of HBECs in vitro induced IL-33 release, triggering production of type-2 cytokines by T cells and group 2 innate lymphoid cells,2 suggesting that IL-33 blockade might prevent downstream type-2 cytokine induction. Anti–IL-33 therapies are currently being studied in asthma clinical trials.

Link between type-2 immunity and IFN impairment in asthma

The study applying transcriptome network analysis in children with asthma demonstrated that high type-2 inflammation and low type-1 IFN responses at baseline were robust predictors of short-term AE risk,1 suggesting that the 2 pathways interact. This hypothesis is supported by type-2 inflammation being associated with increased severity of AE.

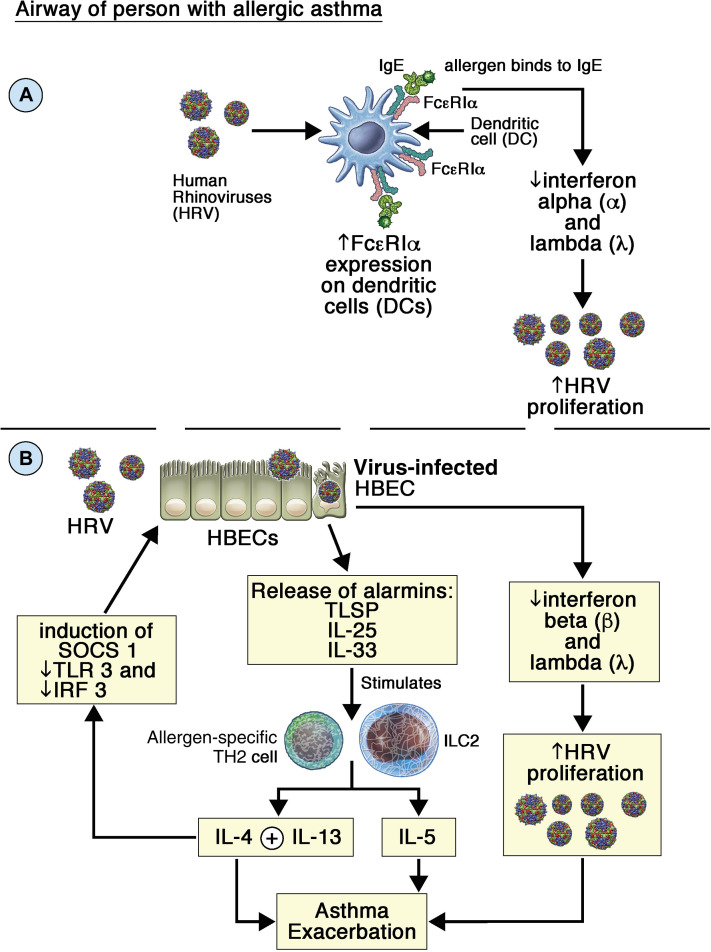

There are several mechanisms that could suppress virus induction of IFNs. Blood DCs from children with atopic asthma (infected with RVs or influenza viruses) display impaired virus-induced IFN-α/IFN-β and IFN-λ release, which correlated with increased high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) expression on DC surfaces. Crosslinking FcεRI with IgE/anti-IgE profoundly suppressed virus-induced IFN release from DCs.6 Thus, IgE induction by type-2 cytokines followed by allergen-induced crosslinking of IgE bound to DCs would profoundly suppress virus induction of IFNs (Fig 1 , A). This mechanism is strongly supported by studies showing that anti-IgE therapy restores impaired IFN responses in people with asthma.6

Fig 1.

A and B, Potential mechanisms of IFN impairment in asthmatic airways. ILC2, Group 2 innate lymphoid cell; SOCS, suppressor of cytokine signaling; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

IL-4 and IL-13 suppress IFN responses in RV-infected HBECs, with suppression of TLR3 expression and IRF3 activation, thus increasing virus replication (Fig 1, B). Both cytokines also induce suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 expression in HBECs, and suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 suppresses virus-induced IFNs in HBECs (Fig 1, B).

Therapeutic approaches to boost antiviral responses in AEs

Azithromycin (AZM) boosts IFN production from virus-infected HBECs and has antiviral activity; it should therefore be beneficial in virus-induced AEs (PMID: 20150207). An observational study reported that macrolide antibiotics were associated with reduction in 120-day risk of AEs (PMID: 27692150). The Effect of azithromycin on asthma exacerbations and quality of life in adults with persistent uncontrolled asthma (AMAZES) trial reported that long-term prophylactic AZM reduced AE frequency by approximately 40% and improved asthma-related quality of life (PMID: 28687413). Furthermore, AZM reduced AEs in both eosinophilic and noneosinophilic patients with asthma and in AEs without bacterial pathogen isolation from sputum, suggesting that its activity was likely independent of antibacterial activity. Further studies on AZM antiviral activity and on its efficacy in AEs are clearly warranted.

Asthma as a risk factor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 infection

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, infects the upper and lower respiratory tracts, entering host cells through the angiotensin-converting-enzyme-2 receptor and the protease TMPRSS-2.7 The World Health Organization highlighted that people with severe asthma are a high-risk group for SARS-CoV-2 infection, and COVID-19 severity, and advocated stringent shielding of these individuals.

Surprisingly though, many studies reported that asthma was no more prevalent among people with COVID-19 of varying degrees of severity than among the general population. These estimates of the risk posed by having asthma may be underestimates because people with asthma are likely taking extra precautions by shielding, wearing masks, and taking their prophylactic asthma medications to protect themselves from COVID-19. OpenSAFELY, a databank with more than 17 million UK primary health care records, reported that severe asthma (defined by recent oral corticosteroid use) was a risk factor for COVID-19 mortality (PMID: 32640463). In addition, patients with asthma on high-dose inhaled corticosteroids had increased COVID-19 mortality risk compared with those on short-acting beta-agonists only.8 However, OpenSAFELY is a retrospective observational study using general practitioner records to define asthma, which may reveal potential associations but cannot define causal relationships.8 Furthermore, the study could not expand on other underlying disease characteristics that may not be captured in primary health care records, which may reveal individuals with an increased susceptibility to viral infections as well as more severe asthma.8

The International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium analyzed more than 75,000 UK COVID-19 hospital admissions and reported that patients 16 years and older, with asthma of any severity, were significantly more likely than patients without asthma to receive critical care. Severe asthma (defined as those taking triple therapy) was a risk factor for COVID-19 mortality.9

Link between asthma endotypes and COVID-19 susceptibility

Emerging evidence suggests that distinct asthma endotypes may have differential risk of COVID-19 severity. An interesting hypothesis would be to investigate the role of asthma endotypes in protection from or susceptibility to COVID-19. Around 50% of patients with asthma are T2-high (Table I ), and recent studies suggest the possibility of type-2 immunity being protective against COVID-19. UK Biobank data reported that nonallergic asthma (but not allergic/atopic asthma) was a risk factor for severe COVID-19.10 This may be because patients with non–type-2 asthma may have higher baseline inflammation due to pre-existing comorbidities, such as obesity and age. These comorbidities may play a more important role in driving COVID-19 severity than the underlying asthma itself (Table I). In addition, atopic patients had significantly lower odds of hospitalization for COVID-19, and atopy was associated with a decreased duration of COVID-19 hospitalization.10 This may be related to reduced angiotensin-converting-enzyme-2 expression levels in atopy, which correlated with allergic sensitization, total IgE levels, and type-2 cytokines.10

Table I.

Potential implications of asthma endotypes on ICS use, COVID-19 risk, and ACE-2 expression

| Asthma endotype | Type-2 | Non–Type-2 |

|---|---|---|

| Patient profile |

|

|

| Immune profile |

|

|

| Treatment |

|

|

| Potential effect on COVID-19 outcome |

|

|

ACE-2, Angiotensin-converting-enzyme-2; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; ILC2, group 2 innate lymphoid cell.

Another major endotype that may be susceptible are individuals with asthma, who also have pre-existing IFN impairment. IFN impairment has been postulated to be the major factor driving disease severity in COVID-19 (PMID: 32661059 and 32972995). A genomewide association study reported that low expression of IFNAR2 was associated with severe COVID-19 (PMID: 33307546). Clinical trials have shown that exogenously administered type-1 IFNs are highly effective treatments for COVID-19 when given early during infection (PMID: 32401715 and 32758689), but even when given late at hospitalization can still significantly improve outcomes and reduce mortality (PMID: 32661006 and 32862111). Such therapies are even more likely to help people with asthma and IFN impairment, and especially so if given early during infection.

Footnotes

S.L.J. is the Asthma UK Clinical Chair (grant no. CH11SJ) and a National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Emeritus Senior Investigator and is funded in part by European Research Council Advanced Grant (grant no. 788575). This research was supported by the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: S. L. Johnston is an author on patents relating to use of inhaled interferons for the treatment of exacerbations of airway disease and is also an author on patents for rhinovirus vaccines. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Altman M.C., Gill M.A., Whalen E., Babineau D.C., Shao B., Liu A.H. Transcriptome networks identify mechanisms of viral and nonviral asthma exacerbations in children. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:637–651. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0347-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson D.J., Makrinioti H., Rana B.M., Shamji B.W., Trujillo-Torralbo M.B., Footitt J. IL-33-dependent type 2 inflammation during rhinovirus-induced asthma exacerbations in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:1373–1382. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1039OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Contoli M., Message S.D., Laza-Stanca V., Edwards M.R., Wark P.A., Bartlett N.W. Role of deficient type III interferon-lambda production in asthma exacerbations. Nat Med. 2006;12:1023–1026. doi: 10.1038/nm1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansel T.T., Tunstall T., Trujillo-Torralbo M.B., Shamji B., Del-Rosario A., Dhariwal J. A comprehensive evaluation of nasal and bronchial cytokines and chemokines following experimental rhinovirus infection in allergic asthma: increased interferons (IFN-γ and IFN-λ) and type 2 inflammation (IL-5 and IL-13) EBioMedicine. 2017;19:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCrae C., Olsson M., Gustafson P., Malmgren A., Aurell M., Fagerås M. INEXAS: a phase 2 randomized trial of on-demand inhaled interferon beta-1a in severe asthmatics. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51:273–283. doi: 10.1111/cea.13765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill M.A., Liu A.H., Calatroni A., Krouse R.Z., Shao B., Schiltz A. Enhanced plasmacytoid dendritic cell antiviral responses after omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1735–1743.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradding P., Richardson M., Hinks T.S.C., Howarth P.H., Choy D.F., Arron J.R. ACE2, TMPRSS2, and furin gene expression in the airways of people with asthma—implications for COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:208–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultze A., Walker A.J., MacKenna B., Morton C.E., Bhaskaran K., Brown J.P. Risk of COVID-19-related death among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma prescribed inhaled corticosteroids: an observational cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:1106–1120. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30415-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloom CI, Drake TM, Docherty AB, Lipworth BJ, Johnston SL, Nguyen-Van-Tam JS, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes in patients with underlying respiratory conditions admitted to hospital with COVID-19: a national, multicentre prospective cohort study using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol UK [published online ahead of print March 4, 2021]. Lancet Respir Med. 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00013-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Skevaki C., Karsonova A., Karaulov A., Xie M., Renz H. Asthma-associated risk for COVID-19 development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:1295–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]