Abstract

Background

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) may reduce substance use and other addictive behaviours. However, the cognitive mechanisms that underpin such effects remain unclear. Impaired inhibitory control linked to hypoactivation of the prefrontal cortex may allow craving-related motivations to lead to compulsive addictive behaviours. However, very few studies have examined whether increasing the activation of the dlPFC via anodal tDCS could enhance inhibitory control over addiction-related distractors. The current study aimed to enrich empirical evidence related to this issue.

Methods

Thirty-three males with Internet gaming disorder underwent active (1.5 mA for 20 minutes) and sham tDCS 1 week apart, in randomized order. We assessed inhibitory control over gaming-related distractors and craving pre- and post-stimulation.

Results

Relative to sham treatment, active tDCS reduced interference from gaming-related (versus non-gaming) distractors and attenuated background craving, but did not affect cue-induced craving.

Limitations

This study was limited by its relatively small sample size and the fact that it lacked assessments of tDCS effects on addictive behaviour. Future tDCS studies with multiple sessions in larger samples are warranted to examine the effects on addictive behaviours of alterations in addiction-related inhibitory control.

Conclusion

These findings demonstrate that stimulation of the dlPFC influences inhibitory control over addiction-related cues and addiction-related motivation. This is the first empirical study to suggest that enhanced inhibitory control may be a cognitive mechanism underlying the effects of tDCS on addictions like Internet gaming disorder. Our finding of attenuated background craving replicated previous tDCS studies. Intriguingly, our finding of distinct tDCS effects on 2 forms of craving suggests that they may have disparate underlying mechanisms or differential sensitivity to tDCS.

Clinical Trials No

Introduction

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a noninvasive brain stimulation technique capable of altering cortical activation.1 This approach — particularly anodal tDCS over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), which increases its cortical activation — has been used in a preliminary way as a potential intervention for addictions.2,3 Specifically, anodal tDCS over the dlPFC has been shown to reduce craving for various substances, including food, cigarettes and cocaine.4–6 However, although considerable previous work has shown that multiple sessions of anodal tDCS over the dlPFC reduce caloric intake7 and addiction-related behaviours such as cigarette smoking,6,8,9 alcohol use10 and gaming,11 other studies have shown no significant effects of tDCS on addictive behaviours. 12 Nevertheless, tDCS has been recommended for its possible use in addiction.13 However, to date no clinically useful predictors of tDCS efficacy have been suggested to help identify who may benefit from tDCS in addictions. The current study aimed to explore the cognitive mechanisms that underlie tDCS effects in people with Internet gaming disorder (IGD) using a brief crossover design (within-subject and sham-controlled). Such explorations could enhance our ability to predict responses to tDCS and help develop individualized treatments and new interventions for IGD.

It has been theorized that alterations in inhibitory control may underlie the efficacy of tDCS in treating addictions.14 Characterized by difficulties in curbing the excessive reward salience of addiction-related substances or cues, and by compulsive addictive behaviours, impaired inhibitory control has been proposed as a core contributor to addictions.15–17 Considerable neuroimaging evidence in addictions has demonstrated that such impairment is involved with relative hypoactivation of the prefrontal cortex (e.g., the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [dlPFC]).18–20 Moreover, some studies have shown that enhanced inhibitory control over cocaine-related distractors is associated with increased activation in the right prefrontal cortex.21 However, very few empirical studies have examined whether increasing activation of the dlPFC via anodal tDCS enhances inhibitory control over addiction-related distractors. The primary aim of the current study was to provide additional empirical evidence for this issue.

An additional aim was to examine the effects of tDCS on 2 forms of craving. Craving is a diagnostic criterion for substance-use disorders in DSM-522 and ICD-11.23,24 Craving involves strong urges to use addictive substances or engage in addictive behaviours,25 and it has been implicated in addiction development, maintenance and relapse.26,27 Most previous studies have examined the effects of tDCS solely with respect to cue-induced craving or background craving, showing that tDCS of the dlPFC reduces one form of craving or the other in addictions.2,6,28 Background craving refers to a nonacute state that may occur over a period of abstinence, for example; cue-induced craving refers to acute and often intense urges triggered by addiction-related stimuli. The 2 forms of craving may involve different mechanisms and contribute differently to addictions. 29 It is important to examine the effects of dlPFC stimulation on both forms of craving in a systematic way to provide insights into the factors that influence these phenomena.

To address the questions above, we used anodal tDCS to increase the cortical excitability of the right dlPFC and assessed the effects of tDCS on inhibitory control over addiction-related distractors and craving (background and cue-induced) in people with IGD, employing a sham-controlled, within-subject, double-blind design. We chose to study people with IGD for the following reasons. First, characterized by poor control over Internet gaming, IGD has been included in section III of DSM-522 as a putative behavioural addiction. Gaming disorder has also recently been included in ICD-11.24 Because of the rapid development of the Internet, IGD is arguably among the fastest-growing addictions.30 Internet gaming has become a part of many people’s daily lives worldwide, increasing the risk of addiction and posing threats to public mental health. Second, considerable research into IGD has shown that its neurobiological underpinnings resemble those of substance-use disorders. 31,32 In particular, and similar to people with substance-use disorders, it has been proposed that people with IGD exhibit blunted activation of the prefrontal cortex in relation to impaired inhibitory control over reward processing and addiction-related (gaming-related) stimuli or behaviours.33 Such phenomena have been shown to be common neural alterations across addictions.15,20 Third, unlike substance addictions, IGD does not have complicating drug-on-brain effects, likely making the study of the cognitive mechanisms that underlie tDCS interventions less confounded. Fourth, although tDCS has been explored in preliminary studies in substance addictions, its efficacy remains to be examined in IGD. We adopted the anodal tDCS technique in the current study for 2 reasons. First, it has been proposed that anodal and cathodal tDCS increase and decrease the activation of targeted cortical regions, respectively.2,3 Second, IGD may be characterized by impaired inhibitory control associated with hypoactivation of the prefrontal cortex.33

We modified a well-validated cognitive task that assesses inhibitory control, in which participants are instructed to perform a cognitive task with emotionally or motivationally salient stimuli as distractors.34 In the current study, we assessed inhibitory control over gaming-related distractors after tDCS. We also assessed background and cue-induced cravings before and after tDCS. Based on previous findings, 2,6,35 we hypothesized that tDCS of the right dlPFC would enhance inhibitory control over gaming-related distractors and attenuate the 2 forms of craving.

Methods

Participants

We conducted eligibility screening of 364 young adults from universities in Beijing, China, recruited via online advertisements. Given that IGD has higher prevalence estimates in males36 and sex-related differences related to craving have been reported,37,38 we included only male participants in the study. Using G*Power 3.1.9.2,39 we calculated the desired sample size before starting the study. Assuming a moderate effect size, the desired sample size was 30 (α = 0.05, power = 0.8, effect size = 0.25).39 To account for potential dropouts, we recruited 38 males (18–25 years old) with IGD. Thirty-three participants completed the entire study; 5 participants discontinued owing to scheduling conflicts with the second visit.

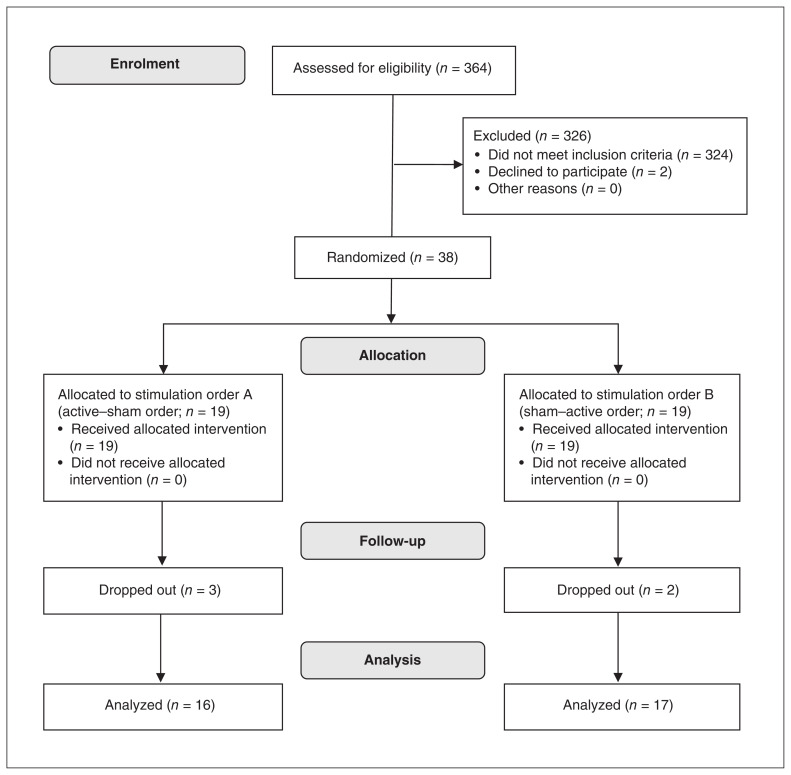

In accordance with previous studies,40,41 primary inclusion criteria for participants with IGD included the following: they met ≥ 5 items of the DSM-5 proposed criteria for IGD; they scored ≥ 50 on a revised version of Young’s online Internet addiction test;42 they spent more than 50% of their online time gaming; and they played Internet games ≥ 20 hours per week for at least 1 year. Exclusion criteria included the presence of metal in the head or face; head trauma; substance dependence; psychiatric or neurologic disorders; use of psychotropic medications; or being left-handed. Detailed exclusion criteria and demographic and clinical information of participants are provided in Appendix 1, available at jpn.ca/190137-a1. The study was approved by a local research ethics committee at the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning at Beijing Normal University. All participants provided written informed consent before participation in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and they were paid for their participation. Figure 1 shows the participant screening and randomization processes.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart depicting the screening and randomization of participants. Advertisements led to the eligibility screening of 364 young adults from universities in Beijing. Thirty-eight eligible participants with Internet gaming disorder were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups using a 1:1 ratio. One group received 2 tDCS sessions in active–sham order, and the other group received 2 tDCS sessions in sham–active order. Thirty-three participants completed the whole study; 5 participants discontinued because of scheduling conflicts with the second visit. tDCS = transcranial direct current stimulation.

Experimental design

This study had a crossover design; it was within-subject, sham-controlled, randomized and double-blind. Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 2 groups using a 1:1 ratio. One group received the 2 tDCS sessions in active–sham order, and the other group received the 2 tDCS sessions in sham–active order. Detailed randomized information about the order of active and sham tDCS sessions for each participant is provided in Appendix 1. Participants received the 2 tDCS sessions 1 week apart.

Assessment of craving

Before each stimulation, we assessed participants’ background and cue-induced craving for Internet gaming in sequence. We assessed background craving by instructing participants to rate their subjective craving for Internet gaming on a 9-point scale (from 1 = “not craving at all” to 9 = “craving very much”), without presenting any gaming-related cues. We assessed cue-induced craving using a cue-reactivity task. Participants watched 3 gaming-related videos; each video lasted 30 seconds and was followed by a 4-second rating using the 9-point scale described above. Participants rated their subjective craving for Internet gaming after watching each video. During each stimulation, participants performed regulation-of-craving and emotion-regulation tasks (data relating to these 2 tasks will be reported elsewhere).

Assessment of inhibitory control

Approximately 20 minutes after tDCS, we assessed participants’ background and cue-induced craving again using the same methods as we used before each stimulation. Then, participants completed a cognitive task that assessed their inhibitory control over addiction-related distractors. In the task, participants performed letter categorization, and gaming-related cues appeared as distractors. The task included gaming-related cues (36 gaming-related pictures), neutral cues (36 non-gaming pictures, including neutral objects and scenes) and mosaic baseline cues (36 scrambled mosaic stimuli of the gaming pictures and 36 scrambled mosaic stimuli of the non-gaming pictures). The gaming pictures belonged to 1 of the 3 most popular Internet games among young adults in China (King of Glory, Playerunknown’s Battlegrounds and League of Legends), in accordance with each participant’s preference.

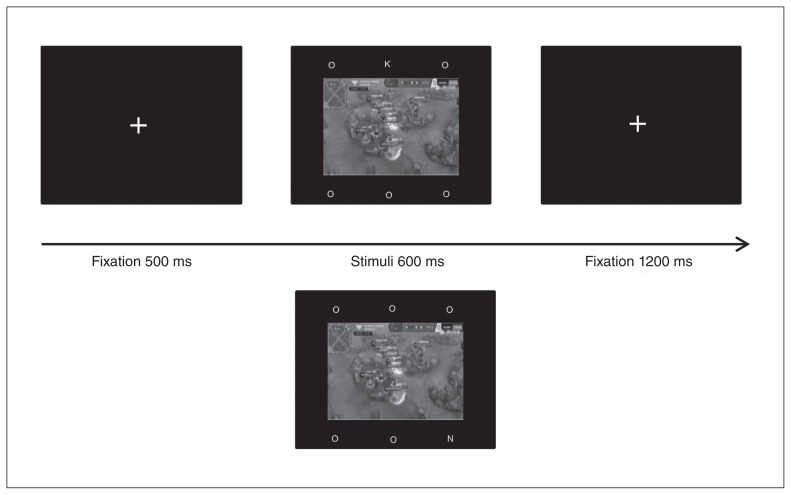

An example of the trial sequence is shown in Figure 2. Each trial started with a fixation (500 ms). Then, a picture was presented (gaming, neutral or mosaic; 600 ms) in the centre of the screen, with 3 letters above the picture and 3 letters below. Five of the letters were “O,” and the targets were “K” or “N.” Participants were instructed to ignore the central picture and judge whether the target letter was “K” or “N” as quickly and accurately as possible. They were given 1800 ms after onset of the stimulus to respond via button press. All pictures were presented in a pseudorandomized order. Meanwhile, target letter and location were counterbalanced across trials, and trial order was pseudorandomized. Each participant completed 144 trials in total: 2 runs with 18 gaming pictures, 18 neutral pictures and 36 corresponding mosaic stimuli in each run. Before the formal experiment, participants completed 20 practice trials.

Fig. 2.

Example of the trial sequence for the task assessing inhibitory control. Participants were instructed to ignore the central picture and judge whether the target letter was K or N.

tDCS protocol

Direct current was delivered through a pair of carbonated silicone electrodes (surface 5 × 7 cm2) with highly conductive gel (Signa Gel, Parker Laboratories) connected to a DC stimulator MC (neuroConn GmBH). For anodal stimulation of the right dlPFC, we placed the anode electrode on F4 in accordance with the 10–20 international EEG system and positioned the cathode on the left superior region of the trapezius muscle near the base of the neck.43 During the active stimulation, a direct current of 1.5 mA was delivered for 20 minutes, with 30 seconds of ramp-up and ramp-down time. The sham tDCS consisted of only the 30 seconds of ramp-up and ramp-down time, which were aimed at making participants feel the same itching sensation as with active tDCS. An assistant experimenter operated the DC stimulator so that both the experimenter and the participant were blind to the stimulation condition.

tDCS-related measures

After each active or sham stimulation, we assessed participants for 10 potential adverse effects of tDCS (headache, scalp pain, neck pain, tingling, itching, burning, flushing of skin, drowsiness, difficulty concentrating and acute mood changes) using a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = “not at all” to 4 = “very much”). Participants were asked to describe the difference between the 2 stimulations after they had completed the whole experiment.

Statistical analysis

In the task assessing inhibitory control over addiction-related distractors, we removed errors and outliers from the response-time analysis. Outliers were defined as response times that exceeded 3 standard deviations above or below the mean in each experimental condition for each participant. First we calculated the interference effects of each picture type (i.e., response times for gaming pictures v. mosaic stimuli of gaming pictures, and response times for neutral pictures v. mosaic stimuli of neutral pictures) in each stimulation condition for each participant. Next, we analyzed the interference effects indexed by differences in response times using repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with 2 within-participant factors: picture type (gaming v. neutral pictures) and stimulation condition (active v. sham). We used the analogous analyses to analyze error rates. For background and cue-induced craving, we analyzed subjective ratings of the 2 forms of craving respectively using ANOVAs with the following within-participant factors: time (pre-stimulation v. post-stimulation) and stimulation condition (real v. sham).

For all ANOVAs, the significance level was set to α = 0.05, and ANOVAs were supplemented by paired 2-tailed t tests where appropriate. Effect sizes were calculated as ηp2.

Results

tDCS effects on inhibitory control over addiction-related distractors

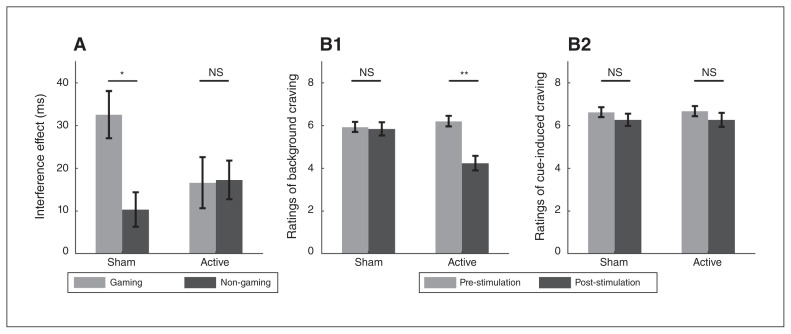

Analyses of the interference effect showed a significant picture-type × stimulation-condition interaction (F1,32 = 4.80, p = 0.04, ηp2 = 0.13; Fig. 3A) Post hoc paired t tests revealed that for the sham tDCS condition, the interference effect from gaming pictures was larger than that from neutral (non-gaming) pictures (t32 = 3.08, p = 0.004; 32.6 v. 10.4 ms). For the active tDCS condition, the interference effects from the 2 picture types revealed no significant difference (t32 = −0.08, p > 0.1; 16.6 v. 17.3 ms). Taken together, active relative to sham tDCS reduced interference from gaming versus non-gaming pictures, indicating enhanced inhibitory control over gaming-related distractors. Analyses of error rates did not reveal significant findings.

Fig. 3.

Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) on inhibitory control and craving. (A) For the sham tDCS condition, the interference effect from gaming pictures was larger than that from non-gaming pictures; for the active tDCS condition, the 2 picture types revealed no significant difference in interference effect. (B1) For the sham tDCS condition, we found no significant difference in background craving between the pre- versus poststimulation conditions; for the active tDCS condition, craving was lower post-stimulation versus pre-stimulation. (B2) Analyses of ratings of cue-induced craving did not reveal significant results. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. NS = not significant.

tDCS effects on background and cue-induced cravings

Analyses of ratings of background craving revealed a significant interaction of time × stimulation condition (F1,32 = 20.54, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.39; Fig. 3B1). Post hoc paired t tests showed no significant difference in background craving between pre- and post-stimulation conditions for sham tDCS (t32 = −0.30, p > 0.1; 5.85 v. 5.94). However, for active tDCS we found a significant difference, whereby background craving was lower post-stimulation compared to pre-stimulation (t32 = −5.64, p < 0.001; 4.24 v. 6.21). Analyses of ratings of cue-induced craving did not reveal significant findings (Fig. 3B2).

tDCS adverse effects and blinding

All participants tolerated tDCS well. The average ratings of adverse effects were equal for both active and sham tDCS (mean ± standard deviation; active = 1.18 ± 0.29; sham = 1.18 ± 0.23). These findings suggested that participants experienced few or no clinically significant adverse effects. Paired t tests revealed no significant differences in adverse effects between active and sham tDCS (p > 0.1). Furthermore, only 7 participants (21%) reported that they could feel the difference between active and sham tDCS, which was not significantly different from chance (1-sample binomial test p > 0.1).

Discussion

The current study provides the first empirical evidence suggesting that enhanced inhibitory control may be a cognitive mechanism underlying the effects of tDCS on addictions, among people with an addiction broadly and with IGD specifically. Active relative to sham tDCS reduced interference of gaming versus non-gaming pictures on task performance. This indicated enhanced inhibitory control toward addiction-related distractors. In addition, ratings of background craving decreased after active versus sham stimulation, replicating previous tDCS findings. Intriguingly, we observed divergent tDCS effects on 2 forms of craving: background craving was reduced, but cue-induced craving remained unchanged. These findings suggest several possibilities. For example, it is possible that the 2 types of craving differ in their underlying mechanisms. Alternatively, it is possible that—given the intense and episodic nature of cue-induced craving —it may be less sensitive to the effects of a single tDCS session than background craving.

With respect to inhibitory control, we observed a significantly larger interference effect from gaming versus non-gaming images in the sham stimulation condition, indicating preferential processing of gaming-related cues in people with IGD. These findings were consistent with those of previous studies showing attentional bias toward addiction-related cues compared with neutral cues among people with addictions.44,45 Importantly, active relative to sham tDCS reduced interference from gaming versus non-gaming images in the current study, suggesting that increasing dlPFC excitability via tDCS enhances inhibitory control over addiction-related distractors. This result was consistent with previous neuroimaging data showing that enhanced inhibitory control over drug-related distractors is associated with increased activation in the right prefrontal cortex.21 With this in mind, the current findings may indicate that enhanced inhibitory control over addiction-related distractors may be an important cognitive mechanism underlying the effects of tDCS on addictions.

With respect to craving, we observed that active relative to sham tDCS diminished background craving but did not affect cue-induced craving. Our findings of a tDCS effect on background craving in the current study replicated the findings of previous tDCS studies,2,28 whereas our findings related to cue-induced craving differed from some previous studies46 but not all.47,48 When comparing these 2 lines of evidence, we suggest that cue-induced craving may be more likely to be attenuated by multiple-session tDCS than by single-session tDCS,6,49 and this possibility should be tested directly for IGD.

The neuromodulatory intervention used here (i.e., single-session tDCS) resulted in different effects on 2 forms of craving. This finding was consistent with previous work suggesting that some interventions (such as the nicotine patch) may decrease background craving but not cue-induced craving among smokers.50 Although both forms of craving are important motivational factors in addictions and regulation of both forms may involve prefrontal cortex function, the findings of the current study suggest that they may differ in their underlying mechanisms, or that cue-induced craving may be less amenable to manipulations more broadly.

Overall, neurostimulation of the dlPFC may influence craving or addictive behaviours in at least 3 ways. First, it may enhance executive control, influencing factors such as attention, motivation and behaviours. As demonstrated in the current study, tDCS of the dlPFC improves inhibitory control over addiction-related distractors. Second, neuromodulation may alter neurotransmission (e.g., increase dopamine release) and alter function in reward systems indirectly by, for example, interconnections between the dlPFC and other structures such as the ventral tegmental area.14,51 This currently speculative notion requires direct examination. Third, neurostimulation of the dlPFC may involve a combination of the aforementioned influences on control and reward systems. Accordingly, this possibility may explain the attenuation of background craving in the current study. Based on a history of repetitive associations between addiction-related cues and behaviours,29 cue-induced craving may involve habitual or seemingly automatic responses to addiction-related cues, which may be intense and difficult to attenuate. Such craving may have neuroadaptations indexed by hyperactivation of reward networks (e.g., the striatum or the orbitofrontal cortex) in response to addiction-related relative to non-addictive stimuli.14 Weakening habit-related neural processes that underlie learned cue-craving associations may require greater improvement of executive control elicited by explicit self-control or inhibitory goals.52 Further, this process may require a relatively long experience of reconfiguring old cue-craving associations and rebuilding new associations. Such changes might be facilitated by multiple tDCS sessions, although this notion is currently speculative. Future research is warranted to directly differentiate the neural mechanisms that underlie alterations in these 2 craving processes, and to examine the efficacy of multiple tDCS sessions.

The current study has important clinical implications in several ways. First, it suggests that enhancement in inhibitory control may be a potential predictor of tDCS efficacy in treating addictions. Multiple-session tDCS studies are warranted to examine the relationship between enhancement in inhibitory control and alleviation in addictive behaviours in the future. Second, given the effects of tDCS on inhibitory control, a combination of tDCS and cognitive training relating to inhibitory control might augment the efficacy of addiction interventions. Third, differential tDCS effects on 2 forms of craving suggest that treatment for each form of craving might call for distinct interventions.

Limitations

Several limitations should be discussed. First, the current study included a relatively small group of young adult male participants from China. However, our sample size was consistent with most previous tDCS studies (previous sample sizes have ranged from approximately 20 to 30).13,49 Our sample size (n = 33) was larger than the desired sample size (n = 30) calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.2 (as described in the Method section, above).39 Although our sample size was sufficient to support the validity of the current findings, future studies should include larger samples of males and females of greater diversity with respect to age and geographic or cultural domains. Second, the current study demonstrated in a preliminary way that enhanced addiction-related inhibitory control may be an important cognitive mechanism underlying tDCS treatment in addictions. Studies using multiple-session tDCS are warranted to examine the relationships between alterations in addiction-related inhibitory control and addictive behaviours.

Conclusion

The current study demonstrated that dlPFC stimulation affected inhibitory control over addiction-related cues as well as addiction-related motivation. This was the first empirical study to suggest that enhanced addiction-related inhibitory control may be a cognitive mechanism underlying the effects of tDCS on addictions such as IGD. The attenuation of background craving in the current study replicated the findings of previous tDCS studies. Intriguingly, distinct tDCS effects on 2 forms of craving in the current study suggested that they may have different underlying mechanisms or differential sensitivity to tDCS intervention.

Footnotes

Competing interests: M. Potenza has consulted for and advised INSYS, Shire, RiverMend Health, Lakelight Therapeutics/Opiant and Jazz Pharmaceuticals; has received research support from the Mohegan Sun Casino and the National Center for Responsible Gaming; has participated in surveys, mailings or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse control disorders or other health topics; and has consulted for law offices and gambling entities on issues related to impulse control or addictive disorders.

Contributors: L. Wu, M. Potenza, N. Zhou, H. Kober, S. Yip and J. Zhang designed the study. L. Wu, X. Shi, J. Xu, L. Zhu, R. Wang and G. Liu acquired the data, which L. Wu and J. Zhang analyzed. L. Wu, X. Shi, L. Zhu, R. Wang, G. Liu and J. Zhang wrote the article, which M. Potenza, N. Zhou, H. Kober, S. Yip, J. Xu and J. Zhang reviewed. All authors approved the final version to be published and can certify that no other individuals not listed as authors have made substantial contributions to the paper.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 31871122 and grant 31700966), the Project of Humanities and Social Sciences from the Ministry of Education in China (grant 15YJA190010) and the Open Research Fund of the State Key Laboratory of Cognitive Neuroscience and Learning (CNLZD1802). M. Potenza’s involvement was supported by the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, the Connecticut Council on Problem Gambling and the National Center for Responsible Gaming. H. Kober’s involvement was supported by National Institute of Drug Abuse grants R01 DA042911, R01 DA043690, and P50 DA09241. The funding agencies did not have input into the content of the manuscript, and the views in the manuscript may not reflect those of the funding agencies.

References

- 1.Naish KR, Vedelago L, MacKillop J, et al. Effects of neuromodulation on cognitive performance in individuals exhibiting addictive behaviors: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;192:338–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shahbabaie A, Hatami J, Farhoudian A, et al. Optimizing electrode montages of transcranial direct current stimulation for attentional bias modification in early abstinent methamphetamine users. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:907. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coles AS, Kozak K, George TP. A review of brain stimulation methods to treat substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2018;27:71–91. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldman RL, Borckardt JJ, Frohman HA, et al. Prefrontal cortex transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) temporarily reduces food cravings and increases the self-reported ability to resist food in adults with frequent food craving. Appetite. 2011;56:741–6. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batista EK, Klauss J, Fregni F, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of targeted prefrontal cortex modulation with bilateral tDCS in patients with crack-cocaine dependence. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18:pyv066. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyv066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boggio PS, Liguori P, Sultani N, et al. Cumulative priming effects of cortical stimulation on smoking cue-induced craving. Neurosci Lett. 2009;463:82–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jauch-Chara K, Kistenmacher A, Herzog N, et al. Repetitive electric brain stimulation reduces food intake in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:1003–9. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.075481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falcone M, Bernardo L, Ashare RL, et al. Transcranial direct current brain stimulation increases ability to resist smoking. Brain Stimul. 2016;9:191–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fecteau S, Agosta S, Hone-Blanchet A, et al. Modulation of smoking and decision-making behaviors with transcranial direct current stimulation in tobacco smokers: a preliminary study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;140:78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klauss J, Penido Pinheiro LC, Silva Merlo BL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of targeted prefrontal cortex modulation with tDCS in patients with alcohol dependence. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;17:1793–803. doi: 10.1017/S1461145714000984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SH, Im JJ, Oh JK, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation for online gamers: a prospective single-arm feasibility study. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:1166–70. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klauss J, Anders QS, Felippe LV, et al. Lack of effects of extended sessions of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) over dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on craving and relapses in crack-cocaine users. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1198. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lefaucheur JP, Antal A, Ayache SS, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128:56–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2016.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansen JM, Daams JG, Koeter MWJ, et al. Effects of non-invasive neurostimulation on craving: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:2472–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:652–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feil J, Sheppard D, Fitzgerald PB, et al. Addiction, compulsive drug seeking, and the role of frontostriatal mechanisms in regulating inhibitory control. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:248–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Argyriou E, Davison CB, Lee TTC. Response inhibition and internet gaming disorder: a meta-analysis. Addict Behav. 2017;71:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luijten M, Machielsen MW, Veltman DJ, et al. Systematic review of ERP and fMRI studies investigating inhibitory control and error processing in people with substance dependence and behavioural addictions. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2014;39:149–69. doi: 10.1503/jpn.130052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Ruiter MB, Oosterlaan J, Veltman DJ, et al. Similar hyporesponsiveness of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex in problem gamblers and heavy smokers during an inhibitory control task. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;121:81–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ely AV, Jagannathan K, Hager N, et al. Double jeopardy: comorbid obesity and cigarette smoking are linked to neurobiological alterations in inhibitory control during smoking cue exposure. Addict Biol. 2020;25:e12750. doi: 10.1111/adb.12750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hester R, Garavan H. Neural mechanisms underlying drug-related cue distraction in active cocaine users. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:270–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rumpf HJ, Achab S, Billieux J, et al. Including gaming disorder in the ICD-11: the need to do so from a clinical and public health perspective. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:556–61. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Criteria for gaming disorder in the eleventh edition of the International Classification of Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [accessed 30 Nov. 2018]. Available: https://icdwho.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fidwhoint%2ficd%2fentity%2f1448597234. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grall-Bronnec M, Sauvaget A. The use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for modulating craving and addictive behaviours: a critical literature review of efficacy, technical and methodological considerations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;47:592–613. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinotti G, Orsolini L, Fornaro M, et al. Aripiprazole for relapse prevention and craving in alcohol use disorder: current evidence and future perspectives. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25:719–28. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2016.1175431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shiffman S, Dunbar M, Kirchner T, et al. Smoker reactivity to cues: effects on craving and on smoking behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:264–80. doi: 10.1037/a0028339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Den Uyl, Gladwin TE, Wiers RW. Transcranial direct current stimulation, implicit alcohol associations and craving. Biol Psychol. 2015;105:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunbar MS, Shiffman S, Kirchner TR, et al. Nicotine dependence, “background” and cue-induced craving and smoking in the laboratory. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;142:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dieter J, Hoffmann S, Mier D, et al. The role of emotional inhibitory control in specific internet addiction—an fMRI study. Behav Brain Res. 2017;324:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinstein A, Livny A, Weizman A. New developments in brain research of internet and gaming disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;75:314–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang JT, Brand M. Editorial: neural mechanisms underlying internet gaming disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:404. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yao YW, Liu L, Ma SS, et al. Functional and structural neural alterations in Internet gaming disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;83:313–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walsh AT, Carmel D, Harper D, et al. Motivation enhances control of positive and negative emotional distractions. Psychon Bull Rev. 2018;25:1556–62. doi: 10.3758/s13423-017-1414-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hester R, Luijten M. Neural correlates of attentional bias in addiction. CNS Spectr. 2014;19:231–8. doi: 10.1017/S1092852913000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rehbein F, Kliem S, Baier D, et al. Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in German adolescents: diagnostic contribution of the nine DSM-5 criteria in a state-wide representative sample. Addiction. 2015;110:842–51. doi: 10.1111/add.12849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong G, Wang Z, Wang Y, et al. Gender-related differences in neural responses to gaming cues before and after gaming: implications for gender-specific vulnerabilities to Internet gaming disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2018a;13:1203–14. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsy084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong G, Zheng H, Liu X, et al. Gender-related differences in cue-elicited cravings in Internet gaming disorder: the effects of deprivation. J Behav Addict. 2018b;7:953–64. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yip SW, Gross JJ, Chawla M, et al. Is neural processing of negative stimuli altered in addiction independent of drug effects? Findings from drug-naive youth with internet gaming disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:1364–72. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong GH, Wang M, Zheng H, et al. Disrupted prefrontal regulation of striatum-related craving in Internet gaming disorder revealed by dynamic causal modeling: results from a cue-reactivity task. Psychol Med. 2020;27:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S003329172000032X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young KS. Internet addiction test (IAT) Allegany (NY): Center for Internet Addiction; 2009. [accessed 14 Oct. 2020]. Available: www.netaddictioncom/resources/internet_addiction_testhtm. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clarke PJF, Browning M, Hammond G, et al. The causal role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in the modification of attentional bias: evidence from transcranial direct current stimulation. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76:946–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campbell DW, Stewart S, Gray CEP, et al. Chronic cannabis use and attentional bias: extended attentional capture to cannabis cues. Addict Behav. 2018;81:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vujanovic AA, Wardle MC, Liu S, et al. Attentional bias in adults with cannabis use disorders. J Addict Dis. 2016;35:144–53. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2015.1116354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fregni F, Liguori P, Fecteau S, et al. Cortical stimulation of the prefrontal cortex with transcranial direct current stimulation reduces cue-provoked smoking craving: a randomized, sham-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:32–40. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kroczek AM, Haussinger FB, Rohe T, et al. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on craving, heart-rate variability and prefrontal hemodynamics during smoking cue exposure. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;168:123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pripfl J, Lamm C. Focused transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex modulates specific domains of self-regulation. Neurosci Res. 2015;91:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song S, Zilverstand A, Gui W, et al. Effects of single-session versus multi-session non-invasive brain stimulation on craving and consumption in individuals with drug addiction, eating disorders or obesity: a meta-analysis. Brain Stimul. 2019;12:606–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.12.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tiffany ST, Cox LS, Elash CA. Effects of transdermal nicotine patches on abstinence-induced and cue-elicited craving in cigarette smokers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:233–40. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diana M. The dopamine hypothesis of drug addiction and its potential therapeutic value. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:64. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kober H, Kross EF, Mischel W, et al. Regulation of craving by cognitive strategies in cigarette smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;106:52–5. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]