Abstract

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection causes a severe respiratory disease with a 3% global mortality. In the absence of effective treatment, controlling of risk factors that predispose to severe disease is essential to reduce coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mortality. Large observational studies suggest that exercise can reduce the risk of all-cause and disease-specific mortality. The aim of this study was to analyze the influence of the baseline physical activity level on COVID-19 mortality

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study that included patients between 18 and 70 years old, diagnosed with COVID-19 and hospitalized in our center between February 15 and April 15, 2020. After discharge all the patients included in the study were contacted by telephone. Baseline physical activity level was estimated using the Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity Scale questionnaire and patients were divided into two groups for comparison: sedentary patients (group 1) and active patients (group 2).

Results

During the study period 552 patients were admitted to our hospital and met the inclusion criteria. Global mortality in group 1 was significantly higher than in group 2 (13.8% vs 1.8%; p < 0.001). Patients with a sedentary lifestyle had increased COVID-19 mortality independently of other risk factors previously described (hazard ratio 5.91 (1.80–19.41); p = 0.003).

Conclusion

A baseline sedentary lifestyle increases the mortality of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. This finding may be of great utility in the prevention of severe COVID-19 disease.

Keywords: COVID-19, Exercise, Physical activity, Physical training, SARS-CoV-2

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| The SARS-CoV-2 infection causes a severe respiratory disease with a 3% global mortality. |

| Patients with cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and smokers) and previous systemic diseases (heart, pulmonary, renal, liver, cerebrovascular disease, or oncological pathologies) have been shown to have a poorer prognosis with coronavirus infection. |

| Large observational studies also suggest that exercise itself can reduce the risk of all-cause and disease-specific mortality and it is associated with decreased levels of inflammation markers. |

| It is reasonable that regular physical activity may influence the evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, favoring a better prognosis. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| In this study, a baseline sedentary lifestyle increases the mortality of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 independently of other previously described risk factors (hazard ratio 5.91 (1.80–19.41); p = 0.003). |

| This finding may be of great utility in the prevention of severe COVID-19 disease. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.13859075.

Introduction

Since the first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan (China) in December 2019 [1], the virus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has rapidly spread throughout the world, being declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization on 11 March 2020. The SARS-CoV-2 infection causes a severe respiratory disease with a 3% global mortality [2]. Initial studies demonstrated that older patients and those with comorbidities have a higher risk of death [3]. Furthermore, patients with cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and smokers) and previous systemic diseases (heart, pulmonary, renal, liver, cerebrovascular disease, or oncological pathologies) have been shown to have a poorer prognosis with coronavirus infection [3–11]. In the absence of effective treatment, the control of these pathologies is essential to reduce COVID-19 mortality. It has long been known that regular physical activity can impact favorably on many of these diseases [12–18]. Large observational studies also suggest that exercise itself can reduce the risk of all-cause and disease-specific mortality [19, 20]. Moreover, patients with severe COVID-19 infections have laboratory evidence of an exuberant inflammatory response that has been associated with critical and fatal illnesses. Exercise is associated with decreased levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 [21, 22]. As such, it is reasonable to hypothesized that regular physical activity may influence the evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, favoring a better prognosis. The aim of this study was to analyze retrospectively the influence of baseline physical activity level (BPAL) on the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Methods

Consecutive patients between 18 and 70 years of age who were hospitalized in our center from February 15 to April 15, 2020 during Spain’s first wave of the pandemic were eligible for inclusion. Hospitalization criteria at that time were based on age, clinical status, and underlying medical conditions, together with fever (body temperature greater than 38 °C), pulmonary infiltrates on chest X-ray, need for supplemental oxygen in order to maintain an oxygen saturation higher than 92%, and laboratory criteria including white blood cell count, CRP, ferritin, and d-dimer. Patients with compatible symptomatology but negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for COVID-19 were excluded. Elderly patients (over 70 years old) were not included in the analysis because of the high prevalence of baseline physical limitations.

All patients included were contacted by telephone after hospital discharge to determine the BPAL. In those patients who died during or after hospitalization, a family member was located to complete the data. The BPAL, before the admission, was estimated using the Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity Scale (RAPA) questionnaire (University of Washington Health Promotion Research Center, © 2006) that has been previously validated in other publications [23, 24]. This test was chosen owing to its simplicity and ease of completion. RAPA is divided into two categories: RAPA 1, aerobic exercise intensity (scored from 1 to 7); and RAPA 2, type of exercise (muscle strength, flexibility or both). For the purpose of this study only RAPA 1 was evaluated. The patients were divided into two groups according to RAPA 1 score:

- Group 1: score 1–3 (sedentary or light physical activity).

- 1: Rarely or never perform any physical activity

- 2: Light or moderate physical activities, but not every week

- 3: Light physical activity every week

- Group 2: score 4–7 (adequate regular activity)

- 4: Moderate physical activities every week, but less than 30 min a day or less than 5 days a week

- 5: Vigorous physical activities every week, but less than 20 min a day or less than 3 days a week

- 6: Thirty minutes or more a day of moderate physical activities, 5 or more days a week

- 7: Twenty minutes or more a day of vigorous physical activities, 3 or more days a week

The interviewers read all these options during the telephone call and the patients chose the one that was more accurate according to their BPAL.

The endpoint of the study was to determine differences between groups 1and 2 in terms of mortality following COVID-19 infection.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were described by absolute frequencies, and relative frequencies were expressed as a percentage. The quantitative variables with a normal distribution according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test were expressed in mean ± standard deviation. The quantitative variables with non-normal distribution were expressed as median and interquartile range. To check interdependence of categorical variables a chi-square test was used. To compare quantitative variables between the two groups a Student’s t test was used if the variables had normal distribution, and a Mann–Whitney U test if they did not. Finally, survival analysis data was performed for the primary endpoint. Possible confounding factors related to the primary endpoint were assessed using Cox regression. Statistically significant differences were considered if the probability of error was less than 5% (p < 0.05). All data was analyzed using the 22th SPSS© program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This protocol was approved by local Clinical Research Ethics Committee under registry number “20/374-E_COVID” on 11 May 2020 and it was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments. All subjects provided informed consent to participate in the study and their consent for publication.

Results

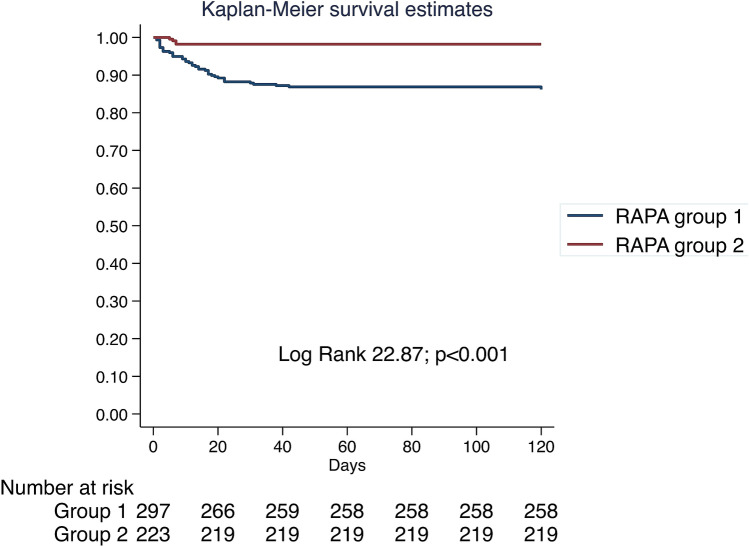

During the study period 556 patients were admitted to our hospital with a diagnosis of COVID-19. After discharge from hospital, BPAL was assessed in 520 patients using the RAPA questionnaire by telephone call. The maximum time to telephone after discharge was 120 days. Thirty-two patients could not be contacted after several attempts, only two of them had died during the hospitalization. Four patients declined the consent to participate in the study and were not included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Inclusion flow diagram

A total of 297 patients were classified as group 1 [score 1, 121 patients (21.9%); score 2, 63 patients (11.4%); score 3, 113 patients (20.5%)] and 223 as group 2 [score 4, 87 patients (15.8%); score 5, 23 patients (4.2%); score 6, 64 patients (11.6%); score 7, 49 patients (8.9%)].

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Group 1 had a significantly higher median age than group 2 (56 vs 53 years old, respectively; p = 0.007). No differences were found in terms of sex or ethnicity. Cardiovascular risk factors were analyzed for the two groups; only hypertension was more frequent in group 1 (36% vs 24.7%; p = 0.006). However, non-cardiovascular comorbidities differed significantly between groups. Group 1 had higher rates of impaired renal function (9.4% vs 1.8%; p < 0.001), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (6.7% vs 2.2%; p = 0.018), cerebrovascular pathologies (6.1% vs 1.3%; p = 0.007), liver disease (6.4% vs 1.8%; p = 0.012), and physical dependency states (7.4% vs 0.8%; p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics and in-hospital outcomes between groups

| Group 1 (n = 297) | Group 2 (n = 223) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56.0 (45.9–64.6) | 52.7 (42.9–60.7) | 0.007 |

| Female gender | 141 (47.5%) | 97 (43.5%) | 0.268 |

| Ethnic group | |||

| Caucasian | 231 (77.8%) | 179 (76.2%) | 0.722 |

| Latino | 56 (18.9%) | 47 (21.1%) | |

| Black | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Asian | 3 (1%) | 3 (1.1%) | |

| Other | 5 (1.7%) | 3 (1.3%) | |

| Hypertension | 107 (36%) | 55 (24.7%) | 0.006 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 (14.8%) | 25 (11.2%) | 0.231 |

| Dyslipidemia | 94 (31.6%) | 57 (25.6%) | 0.118 |

| Active smoker | 20 (6.7%) | 8 (3.6%) | 0.131 |

| Former smoker | 45 (14.2%) | 25 (11.2%) | 0.230 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | 70 (23.6%) | 36 (16.1%) | 0.086 |

| Heart disease | 34 (11.4%) | 18 (8.1%) | 0.205 |

| Coronary disease | 10 (3.4%) | 6 (2.7%) | 0.658 |

| Valvular disease | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.606 |

| Heart failure | 7 (2.4%) | 2 (0.9%) | 0.312 |

| Mixed cardiomyopathy | 7 (2.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.146 |

| Arrhythmias | 8 (2.7%) | 8 (3.6%) | 0.559 |

| Impaired renal function | 28 (9.4%) | 4 (1.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary disease | 51 (17.2%) | 25 (11.2%) | 0.057 |

| Asthma | 14 (4.7%) | 13 (5.8%) | 0.570 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 20 (6.7) | 5 (2.2%) | 0.018 |

| Restrictive disease | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.606 |

| Other | 15 (5.1%) | 6 (2.7%) | 0.176 |

| Home oxygen therapy | 5 (1.7%) | 5 (2.1%) | 0.752 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 18 (6.1%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0.007 |

| Connective tissue disease | 15 (5.1%) | 4 (1.8%) | 0.050 |

| Liver disease | 19 (6.4%) | 4 (1.8%) | 0.012 |

| Malignancy | 36 (12.2%) | 20 (9%) | 0.234 |

| Physical dependency states | 22 (7.4%) | 2 (0.9%) | < 0.001 |

As shown in Table 2 both groups were similar in terms of symptoms and signs associated with the infection but group 1 presented with tachypnea more frequently than group 2 (18.5% vs 9.4%; p = 0.004) and less frequently had fever as an initial symptom (81.1% vs 87.9%; p = 0.043). There was a tendency to lower initial oxygen saturation in group 1 but this did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Symptoms, signs, and main analytical findings at admission

| Symptoms and signs | |||

| Admission SatO2 (%) | 93.0 (89.5–98.0) | 96 (93–98) | 0.075 |

| Asymptomatic | 10 (3.4%) | 7 (3.1%) | 0.911 |

| Dyspnea | 166 (55.9%) | 126 (56.5%) | 0.853 |

| Tachypnea (> 20 bpm) | 55 (18.5%) | 21 (9.4%) | 0.004 |

| Asthenia | 105 (35.4%) | 62 (27.8%) | 0.052 |

| Hypo/anosmia | 26 (8.8%) | 22 (9.9%) | 0.621 |

| Dysgeusia | 20 (6.7%) | 23 (10.3%) | 0.125 |

| Sore throat | 18 (6.1%) | 13 (5.8%) | 0.944 |

| Fever (> 38 °C) | 241 (81.1%) | 196 (87.9%) | 0.043 |

| Cough | 230 (77.4%) | 173 (77.6%) | 0.912 |

| Vomiting | 23 (7.7%) | 11 (4.9%) | 0.221 |

| Diarrhea | 78 (26.3%) | 48 (21.5%) | 0.251 |

| Myalgia | 93 (31.3%) | 82 (36.8%) | 0.135 |

| Main analytical findings | |||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.80 (0.65–1.00) | 0.79 (0.66–0.96) | 0.875 |

| Leukocytes (U/mm3) | 5900 (4600–8300) | 5800 (4500–7900) | 0.674 |

| Lymphocytes (U/mm3) | 900 (600–1400) | 1000 (600–1300) | 0.733 |

| Platelets (103 U/mm3) | 194 (146–255) | 205 (150–257) | 0.523 |

| Raised d-dimer (> 500 ng/ml) | 186 (62.6%) | 130 (58.3%) | 0.223 |

| Raised procalcitonin (> 0.05 ng/ml) | 76 (25.6%) | 49 (22%) | 0.286 |

| Raised C-reactive protein (> 0.5 mg/dl) | 279 (93.9%) | 200 (89.7%) | 0.036 |

| Raised troponin I (> 0.05 ng/ml) | 17 (5.7%) | 10 (4.5%) | 0.528 |

| Raised transaminases (> 40 U/l) | 142 (47.8%) | 104 (46.6%) | 0.775 |

| Raised ferritin (> 340 mg/dl) | 176 (59.3%) | 132 (59.2%) | 0.767 |

| Raised lactate dehydrogenase (> 480 U/l) | 225 (75.8%) | 167 (74.9%) | 0.435 |

No differences were found in the main blood analysis findings at admission except CRP, which was more frequently raised in group 1 (93.9% vs 89.7%; p = 0.036).

Group 1 had poorer outcomes during the admission than group 2 (Table 3); patients in group 1 more frequently developed systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (18.9% vs 12.1%; p = 0.042), respiratory failure (53.9% vs 35.9%; p < 0.001), and renal failure (14.5% vs 6.3%; p = 0.003), which resulted in a longer in-hospital stay (median 8 vs 7 days; p = 0.024).

Table 3.

Infection severity and treatment

| Infection severity | |||

| Hospital stay (days) | 8 (5–13) | 7 (5–10) | 0.024 |

| Maximum temperature (°C) | 37.9 (37–38.5) | 38.0 (37–38.8) | 0.117 |

| Pneumonia | 276 (92.9%) | 203 (91%) | 0.297 |

| Unilateral | 51 (17.2%) | 45 (20.2%) | 0.395 |

| Bilateral | 225 (75.8%) | 158 (70.9%) | 0.172 |

| Sepsis | 49 (16.5%) | 24 (10.8%) | 0.072 |

| Systemic inflammatory response syndrome | 56 (18.9%) | 27 (12.1%) | 0.042 |

| Respiratory failure | 160 (53.9%) | 80 (35.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure | 11 (3.7%) | 3 (1.3%) | 0.101 |

| Renal failure | 43 (14.5%) | 14 (6.3%) | 0.003 |

| Therapy during the hospitalization | |||

| Corticosteroids | 103 (34.7%) | 55 (24.7%) | 0.011 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 253 (85.2%) | 194 (87%) | 0.548 |

| Lopinavir–ritonavir | 200 (67.3%) | 176 (78.9%) | 0.002 |

| Interferon-β1 | 23 (7.7%) | 22 (9.9%) | 0.417 |

| Tocilizumab | 39 (13.1%) | 23 (10.3%) | 0.300 |

| Anticoagulation | 124 (41.8%) | 85 (38.1%) | 0.976 |

| Respiratory support | |||

| Oxygen therapy | 206 (69.4%) | 137 (61.4%) | 0.070 |

| High-flow nasal cannula | 72 (24.2%) | 53 (23.8%) | 0.864 |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 48 (16.2%) | 50 (22.4%) | 0.066 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 23 (7.7%) | 10 (4.5%) | 0.135 |

| Prone position for ventilation | 28 (9.4%) | 21 (9.4%) | 0.949 |

| Critical care unit admission | 26 (8.8%) | 14 (6.3%) | 0.294 |

Categorical variables were described by absolute frequencies and relative frequencies were expressed as a percentage. The quantitative variables that presented non-normal distribution were expressed in median and interquartile range

BMI body mass index, bmp breaths per minute, SatO2 oxygen saturation

Treatment differences during the hospitalization were also analyzed between the two groups. Patients in group 1 more frequently received corticosteroids (34.7% vs 24.7%; p = 0.011) but less frequently were prescribed lopinavir–ritonavir therapy (67.3% vs 78.9%; p = 0.002). No differences were found in the use of hydroxychloroquine, interferon-β1, tocilizumab, or anticoagulation. No differences were found in the use of respiratory support or intensive care unit admission (Table 3).

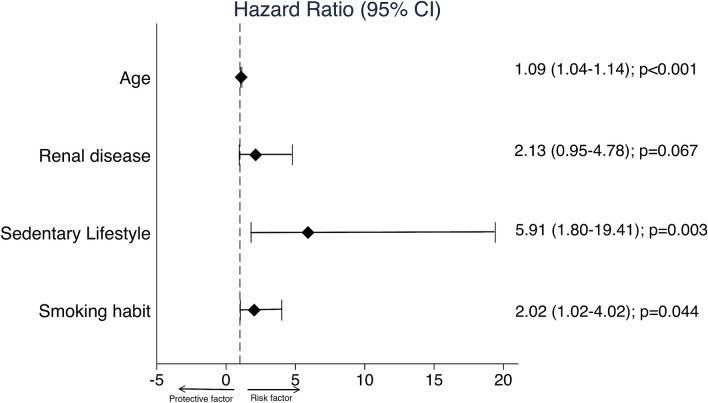

Global mortality was 8.7% (45 patients) in our series being more frequent in group 1 (41 patients (13.8%) vs 4 patients (1.8%); p < 0.001). A survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier method; the results are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis

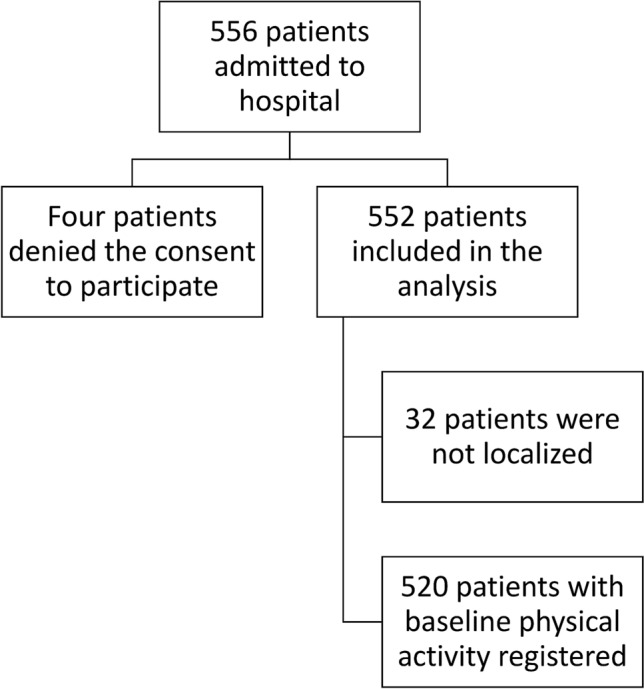

In order to detect possible confounding factors that could influence the impact of BPAL on mortality, other risk factors that have been associated with prognosis in COVID-19 infection were analyzed independently through a univariable Cox regression (Table 4). Multivariable Cox regression showed that sedentary lifestyle, smoking habit, age, and renal disease were independent predictors of mortality in patients with COVID-19. Figure 3 shows the hazard ratio (95% confidence interval) and the respective p values.

Table 4.

Mortality

| HR | 95% CI | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | |||

| Sedentary lifestyle | 8.13 | 2.91 | 22.70 | < 0.001 |

| Age (per 1-year increased) | 1.09 | 1.06 | 1.13 | < 0.001 |

| Male | 1.83 | 0.99 | 3.37 | 0.054 |

| Non-Caucasian race | 0.70 | 0.33 | 1.50 | 0.357 |

| Hypertension | 3.54 | 1.98 | 6.34 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.54 | 0.74 | 3.18 | 0.246 |

| Obesity | 1.58 | 0.83 | 3.01 | 0.164 |

| Smoking habit (former and active) | 3.57 | 1.99 | 6.41 | < 0.001 |

| Renal disease | 4.75 | 2.36 | 9.55 | < 0.001 |

| Pulmonary disease | 3.35 | 1.83 | 6.12 | < 0.001 |

| Heart disease (coronary disease and heart failure) | 2.69 | 1.06 | 6.80 | 0.037 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 5.58 | 2.61 | 11.94 | < 0.001 |

| Connective tissue disease | 3.28 | 1.30 | 8.31 | 0.012 |

| Liver disease | 2.79 | 1.10 | 7.06 | 0.030 |

| Malignancy | 4.09 | 2.17 | 7.71 | < 0.001 |

| Physical dependency | 6.50 | 3.23 | 13.08 | < 0.001 |

Univariate Cox regression

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio

Fig. 3.

Multivariable Cox regression

Discussion

Main Findings

This study analyzed the evolution of the patients admitted to our center during the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic with a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection. Patients were divided into two categories according to the level of physical activity: group 1 or sedentary patients, and group 2 or active patients. The main findings are as follows: (1) despite similar symptoms at admission, sedentary patients had poor in-hospital outcomes with increased SIRS, renal failure, and respiratory failure; (2) overall mortality was higher in sedentary patients; (3) sedentary lifestyle was an independent predictor of mortality on multivariate Cox regression analysis. In the following paragraphs we will discuss these findings in more detail.

In our study, sedentary patients had a higher median age and more comorbidities such as hypertension, renal failure, COPD, cerebrovascular, connective tissue, and liver disease. Physical dependence was also more common. As a result, group 1 represents a cohort of patients with an increased baseline risk of poor COVID-19 prognosis. However, no differences were found at admission in most of the symptoms and physical signs of COVID-19 between both groups except a higher frequency of tachypnea in group 1 and fever in group 2. Patients in group 2, who undertake regular moderate intensity physical activity, might have better respiratory capacity and reserve than group 1 as discussed below, which may result in a better compensatory ability during respiratory illness. The fact that group 2 more frequently presented with pyrexia most likely represents a selection bias regarding the criteria for admission which were set by the hospital at the time of the first wave. The lack of pyrexia as a presenting symptom in group 1 may be reflective of the older age (fever can be absent in 30–50% of older patients) and higher rate of connective tissue disorders in this group (often requiring treatment with immunosuppressive therapy) [25].

Although a higher incidence of pneumonia was expected in group 1, in our study the presence of both unilateral and bilateral pneumonia was similar in both groups. Again, this may be reflective of a selection bias with pneumonia diagnosed on chest X-ray being one of the main criteria to warrant admission in our hospital. However, SIRS and respiratory and renal failure were significantly more frequent in group 1, representing a poorer evolution during hospitalization. This could also explain why the use of corticosteroids was more frequent in group 1. During the first wave of the pandemic, treatment regimens were not standardized. In our center first-line therapy included lopinavir/ritonavir and hydroxychloroquine. Corticosteroids, tocilizumab, and interferon were reserved for patients with worse clinical status or with severe inflammatory component, as occurred more frequently in group 1.

Surprisingly, despite the increased respiratory failure and SIRS in group 1, no statistically significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of respiratory support and intensive care unit admissions. Probably group 1, with a higher burden of comorbidities and lower probability of recovering, may have been less likely to be selected for ICU admission.

Mortality analysis showed an eightfold higher risk of death in group 1 versus group 2. Multivariable analysis showed that sedentary lifestyle was an independent risk factor for mortality in those patients requiring hospitalization for COVID-19 in our center. Expressed in another way, a regular moderate to high intensity physical activity seems to reduce the mortality related to COVID-19 infection. To the best of our knowledge, this finding has not been previously demonstrated and represents a significant benefit of regular exercise in the prognosis of COVID-19. As such, recommending regular physical exercise might be a simple preventative measure, which could have a real impact on mortality during the coming waves of the pandemic. In the following paragraphs several possible mechanisms that have been proposed in the literature to explain the possible effect of physical exercise on the prognosis of coronavirus infection will be discussed.

Physiological Respiratory Adaptations in Physically Trained Patients

Exercise results in a decrease in basal minute ventilation to achieve a given oxygen uptake and an increased in the maximal oxygen uptake during exercise [26]. This could have preconditioned group 2 to have a greater resistance to hypoxemia at comparable degrees of lung disease. This is supported by the fact that in our series, group 2 had a tendency to higher oxygen saturation at admission and less incidence of respiratory failure despite similar pneumonia severity in X-ray.

Exercise and Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

Randomized clinical trials consistently show that participants assigned to moderate exercise programs experienced reduced upper respiratory tract infections incidence and duration [27]. In the study by Nieman et al. a group of 1002 adults were followed for 12 weeks during the winter and fall seasons. In their analysis, the number of days with upper respiratory tract infection was 43% lower in subjects engaging in an average of 5 or more days per week of aerobic exercise compared with those who were largely sedentary [28]. Although there are no specific studies, this could be applicable to COVID-19 infection.

Exercise and Inflammation

There is evidence that lifelong training has an overall anti-inflammatory influence mediated through multiple pathways: enhanced innate immune function, release of muscle myokines that stimulate production of IL-1ra and IL-10, decrease in dysfunctional adipose tissue, and improved oxygenation [27]. In adults with higher levels of physical activity and fitness, epidemiologic studies consistently show reduced white blood cell count, CRP, IL-6, IL-18, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and other inflammatory biomarkers [29–31]. This could have protected group 2 from presenting exuberant inflammatory responses that are frequent in critical forms of COVID-19. As previously commented, patients in the sedentary group had a significantly higher frequency of raised CRP and SIRS.

Exercise and Renin Angiotensin System (RAS)

The angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 has been proposed as the receptor for SARS-CoV-2 protein in the alveolar epithelial cells in the lungs, and pharmacological manipulation of the RAS has been discussed as a potential therapy for COVID-19 [32]. It was reported that decreasing angiotensin II with pharmacological strategies can improve angiotensin 1–7 and attenuate inflammation, fibrosis, and lung injury [33] In the same way, regular physical exercise also induces a shift in the RAS towards angiotensin 1–7 which may possibly reduce the severity of clinical outcome of COVID-19 infection.

Other Predictors of Mortality

As a secondary finding our study also confirmed that age, smoking habit, and renal disease are independent risks factors for mortality as has been noted in previous studies. No statistically significant relationship was found for gender, hypertension, obesity, non-Caucasian races, diabetes, pulmonary, heart, cerebrovascular, liver, and connective tissue diseases, or malignancy, although the trends are consistent with the data previously published. This is in contrast to other series where these comorbidities have been strongly associated with the prognosis of COVID-19, specifically in a recent publication which analyzed almost 11,000 COVID-19 deaths [7]. This difference may be explained by our inclusion criteria, which included patients between 18 and 70 years. Almost 20% of the patients included in the series by Williamson et al. were older than 70 years and in this study, patients over 80 years had a 20-fold higher rate of death than those under 60 years. The exclusion of patients older than 70 years in our series may have limited the ability to demonstrate a statistically significant relationship between mortality and the previously mentioned pathologies because they were not fully represented in this cohort. Furthermore, previous studies have stratified these comorbidities according to their severity, while in our cohort these comorbidities are presented as dichotomous variables (being present or absent). Therefore, the lack of association of previously demonstrated risk factors for mortality in our cohort may be more related to the design of our study rather than a lack of association.

Limitations

This is a single-center retrospective study in which only patients who required hospital admission were included. Those patients who were managed on an outpatient basis were not included. Patients who died before obtaining medical attention or in whom the diagnosis of COVID-19 could not be confirmed by PCR were not included either. The importance of the BPAL in these groups might have been different and further work is required to confirm the impact in these cohorts. The effect of other potential confounding variables not included in the analysis cannot be quantified.

Assessment of BPAL was performed after hospital discharge through a self-evaluation questionnaire that could be highly influenced by the physical and emotional state of patients after overcoming the disease. Besides, in those patients who died during or after hospitalization (45 patients) the questionnaire was completed using information facilitated by relatives, which may have impacted the reporting of BPAL. However, in the context of the limitations imposed by the pandemic (isolation and confinement measures), the RAPA questionnaire provided a simple and easy to understand tool that could be administered by telephone. Nevertheless, prospective studies with a more exhaustive analysis of the BPAL are necessary to confirm the results of this study.

Conclusions

A baseline sedentary lifestyle is an independent risk factor for mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. This represents an important finding and suggests the utility of exercise in prevention of severe COVID-19 presentations.

Acknowledgements

We thank Stuart J. Pocock for his statistical advice and his useful suggestions. We also thank the participants of the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the “Foundation for Biomedical Research” of Clinico San Carlos Hospital.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Ricardo Salgado-Aranda, Nicasio Pérez-Castellano, Ivan Núñez-Gil, A. Josué Orozco, Norberto Torres-Esquivel, Jesús Flores-Soler, Ahmed Chamaisse-Akari, Angela Mclnerney, Carlos Vergara-Uzcategui, Lin Wang, Juan José González-Ferrer, David Filgueiras-Rama, Victoria Cañadas-Godoy, Carlos Macaya-Miguel, and Julián Pérez-Villacastín declare that they have no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study has received approval from Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Clinico San Carlos Hospital under registry number “20/374-E_COVID” on 11 May 2020; and it was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments. All subjects provided informed consent to participate in the study and their consent for publication.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social—Professionals—Situación actual Coronavirus. https://www.mscbs.gob.es/en/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov-China/situacionActual.htm. Accessed 2020 Jul 18.

- 3.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY, Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109:531–538. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tartof SY, Qian L, Hong V, et al. Obesity and mortality among patients diagnosed with COVID-19: results from an integrated health care organization. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:773–781. doi: 10.7326/M20-3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584(7821):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lighter J, Phillips M, Hochman S, et al. Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for COVID-19 hospital admission. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:896–897. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chow N, Fleming-Dutra K, Gierke R, et al. Preliminary estimates of the prevalence of selected underlying health conditions among patients with coronavirus disease 2019—United States, February 12–March 28, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):382–386. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;22:369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Craig CL, Bouchard C. Sitting time and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41(5):998–1005. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181930355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warren TY, Barry V, Hooker SP, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN. Sedentary behaviors increase risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(5):879–885. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c3aa7e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2012;55(11):2895–2905. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2677-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shiroma EJ, Lee I-M. Physical activity and cardiovascular health: lessons learned from epidemiological studies across age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Circulation. 2010;122(7):743–752. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.914721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(1):30–67. doi: 10.3322/caac.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyu HH, Bachman VF, Alexander LT, et al. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer, colon cancer, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, and ischemic stroke events: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. BMJ. 2016;354:i3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Michaud DS, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Fuchs CS. Physical activity, obesity, height, and the risk of pancreatic cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;286(8):921–929. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyberg ST, Singh-Manoux A, Pentti J, et al. Association of healthy lifestyle with years lived without major chronic diseases. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):760–768. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:2024–2035. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aggio D, Papachristou E, Papacosta O, et al. Association between 20-year trajectories of non-occupational physical activity from midlife to old age and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease: a 20-year longitudinal study of British men. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(11):2315–2323. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwy157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamer M, Sabia S, Batty GD, et al. Physical activity and inflammatory markers over 10 years: follow-up in men and women from the Whitehall II cohort study. Circulation. 2012;126(8):928–933. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.103879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lobelo F, Rohm Young D, Sallis R, et al. Routine assessment and promotion of physical activity in healthcare settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137(18):e495–e522. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Topolski TD, LoGerfo J, Patrick DL, Williams B, Walwick J, Patrick MB. The Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity (RAPA) among older adults. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(4):A118. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Henschke PJ. Infections in the elderly. Med J Aust. 1993;158(12):830–834. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb137672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreira JBN, Wohlwend M, Wisløff U. Exercise and cardiac health: physiological and molecular insights. Nat Metab. 2020;2:829–839. doi: 10.1038/s42255-020-0262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nieman DC, Wentz LM. The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. J Sport Health Sci. 2019;8:201–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jshs.2018.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nieman DC, Henson DA, Austin MD, Sha W. Upper respiratory tract infection is reduced in physically fit and active adults. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(12):987–992. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.077875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons TJ, Sartini C, Welsh P, et al. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and inflammatory and hemostatic markers in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(3):459–465. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wedell-Neergaard AS, Krogh-Madsen R, Petersen GL, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and the metabolic syndrome: roles of inflammation and abdominal obesity. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Shanely RA, Nieman DC, Henson DA, Jin F, Knab AM, Sha W. Inflammation and oxidative stress are lower in physically fit and active adults. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23(2):215–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426(6965):450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.South AM, Tomlinson L, Edmonston D, Hiremath S, Sparks MA. Controversies of renin–angiotensin system inhibition during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:305–357. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0279-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.