Abstract

Objectives

To examine patterns of change in later-life social connectedness: (a) the extent and direction of changes in different aspects of social connectedness, including size, density, and composition of social networks, network turnover, and three types of community involvement and (b) the sequential nature of these changes over time.

Method

We use three waves of nationally representative data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project, collected from 2005/2006 to 2015/2016. Respondents were between the ages of 67 and 95 at follow-up. Types of changes in their social connectedness between the two successive 5-year periods are compared to discern over-time change patterns.

Results

Analyses reveal stability or growth in the sizes of most older adults’ social networks, their access to non-kin ties, network expansiveness, as well as several forms of community involvement. Most older adults experienced turnover within their networks, but losses and additions usually offset each other, resulting in generally stable network size and structural features. Moreover, when older adults reported decreases (increases) in a given form of social connectedness during the first half of the study period, these changes were typically followed by countervailing increases (decreases) over the subsequent 5-year period. This general pattern holds for both network and community connectedness.

Discussion

There is an overwhelming tendency toward either maintaining or rebalancing previous structures and levels of both personal network connectedness and community involvement. This results in overall homeostasis. We close by discussing the need for a unifying theoretical framework that can explain these patterns.

Keywords: Homeostasis, Life changes, Longitudinal methods, Social networks

Social connections are important to older adults for a variety of reasons, including health and well-being and access to social support (Cornwell, Laumann, & Schumm, 2008; Coyle & Dugan, 2012; Ellwardt, van Tilburg, Aartsen, Wittek, & Steverink, 2015; Li & Zhang, 2015). As data have become available, scholars have turned their attention to the nature and implications of changes in social connectedness in later life (e.g., Badawy, Schafer, & Sun, 2019; Bookwala, 2016; Cornwell et al., 2014; Cornwell & Laumann, 2015; Fischer & Beresford, 2015; Roth, 2019; Schwartz & Litwin, 2018; van Tilburg, 1998). How individuals’ social lives continually change in the midst of aging has major implications for our understanding of the challenges of later-life transitions.

Indeed, the earliest perspectives on later-life social connectedness were concerned with how older adults’ social lives change over time, not just how connected older adults are at a given time. Cumming and Henry (1961) stimulated this dialogue with their argument that later life involves increasing social isolation. Scholars have since developed alternative models. Some argue that later life is characterized by adaptation and compensation (Atchley, 1989; Kohli, Hank, & Künemund, 2009; Moen, Dempster-McClain, & Williams, 1992). For example, some scholars point to compensatory efforts by older adults to “maintain, enhance, and remediate” their abilities and resources in the midst of potential “failure” experiences that could otherwise reduce their control in everyday life (see Baltes & Baltes, 1990; Heckhausen & Schulz, 1993). Other scholars suggest that there is some (albeit, very selective) pruning of social ties in later life (e.g., Charles & Carstensen, 2010).

Partly due to a lack of representative data, we know little about the nature of change in older adults’ social connections. The National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP)—a nationally representative study of older Americans—recently completed its third wave of data collection. The data were collected in 5-year increments, from 2005/2006 to 2015/2016, yielding longitudinal information that allows us to address two related issues. First, how do older adults’ social connections change over long successive time periods? We document changes in the size, composition, and structure of their social networks, the extent of network turnover (i.e., the loss and/or addition of network members), as well as changes in levels of community involvement. Second, how are changes in older adults’ social lives sequenced? Some early theories—especially the work of Cumming and Henry’s (1961)—suggested that changes will be steady and unidirectional (e.g., constant decline), whereas others have suggested that changes will be adaptive or compensatory in response to earlier changes (e.g., Atchley, 1989; Donnelly & Hinterlong, 2010; Li, 2007; Utz, Carr, Nesse, & Wortman, 2002).

Our overarching goal, then, is to provide a close look at the patterns of changes in social connectedness that so concerned foundational research (e.g., Atchley, 1989; Cumming & Henry, 1961; Moen et al., 1992) on the role of aging in social life.

Dynamics of Social Connectedness in Later Life

We begin with a brief overview of common causes and trajectories, or patterns, of change in different aspects of social connectedness in later life. We then discuss how these changes occur in succession to form larger overarching trajectories of change for older adults.

Typical Patterns of Change

Older adults often experience major changes in their social lives due to life-course transitions. These include retirement, bereavement, health decline, and the emptying of the familial nest (e.g., Crisp, Windsor, Butterworth, & Anstey, 2015; Crosnoe & Elder, 2002; Moen et al., 1992; Perry & Pescosolido, 2012; Pillemer et al., 2000; Schafer, 2013; Shaw, Krause, Liang, & Bennett, 2007). In addition, people are exposed to broader structural processes in their social environments—such as residential turnover, and the opening and closing of local institutions—that are often beyond their control (e.g., see Cornwell, 2015; Goldman & Cornwell, 2018).

As a result of these life-course transitions, older adults’ social lives are usually highly dynamic. Few have stable, unchanging social environments for any long period of time. This is true even of the closest, most stable parts of one’s social network. This relates to several processes, including residential mobility, retirement, the onset of health problems, and confidant mortality. Such changes can have long-term, downstream implications for things like health, especially if those lost contacts are not replaced (e.g., see Cornwell & Laumann, 2015; Giordano & Lindstrom, 2010; Seeman et al., 2011; Thomas, 2012). But network losses are often accompanied by concurrent network additions, the cultivation of which can be a beneficial process (see Cornwell & Laumann, 2015).

In short, the social-gerontological literature emphasizes that later life is usually a period of change and adaptation. But different scholars have argued that the various life-course transitions and other events that older adults experience give rise to different overarching trajectories of change in their social connectedness.

Disengagement and selectivity

The main thrust of much of the foundational research on this topic was that the upheavals of later life lead to the continuous diminution of one’s social roles and positions (e.g., due to retirement), and the voluntary shedding of network ties (Cumming & Henry, 1961). A more recent argument is that (perceived) dwindling life spans prompt older adults to tailor their networks carefully—particularly by forsaking casual acquaintances in favor of spending their remaining time in more emotionally meaningful relationships (Charles & Carstensen, 2010). This model of “socioemotional selectivity” shares the idea that trajectories of change in later-life social connections are characterized by a dwindling stock of social ties, but argues that this occurs mainly in the peripheries of one’s social life. This results in smaller networks that are increasingly kin-centric and, therefore, characterized by greater internal density. This perspective emphasizes the social-psychological mechanisms by which people link their perspectives of time to emotional investments in social ties.

Other work implies that many older adults will experience gradual or continual declines in their social connectedness as they become physically and/or mentally incapacitated. Health decline reduces individuals’ abilities to maintain relationships, particularly weak ties or peripheral contacts (Cornwell, 2009; Schafer, 2011, 2013). To the extent that later life is characterized by health decline, one should expect steady reductions in social network range and in community involvement. Furthermore, chronically ill people come to depend on networks that are capable of coordinated support, which implies denser networks.

Fluctuation and continuity

Many scholars view life-course transitions as experiences whose effects on social connectedness depend on individuals’ responses to those challenges. Older adults exhibit positive, adaptive responses to later-life transitions that may otherwise threaten their social integration. Continuity and activity theories, in particular, hold that people grow accustomed to certain social roles and activities and attempt to maintain them in the midst of later-life transitions (Atchley, 1989; Donnelly & Hinterlong, 2010; Moen et al., 1992; Utz et al., 2002). The loss of social ties thus sparks efforts by individuals to adapt—which they do by cultivating new relationships and by becoming more socially involved (e.g., Donnelly & Hinterlong, 2010; Johnson & Mutchler, 2014; Lamme, Dykstra, & van Groenou, 1996; Li, 2007; Mutchler, Burr, & Caro, 2003). Many older adults treat their transitions out of one social role domain (e.g., retirement) as opportunities to become more socially active in others (e.g., volunteering). Thus, these accounts often emphasize older adults’ engagement in new social domains as efforts to compensate for the loss of other social ties.

This research highlights the interplay between the two types of social connectedness that we examine in this paper—network connectedness and community involvement. Fluctuations in one domain have been linked to fluctuations in the other. For instance, religious involvement and other forms of social participation tend to increase following some later-life transitions, such as widowhood (e.g., see Brown, Nesse, House, & Utz, 2004; Utz et al., 2002). People who adjust to events like widowhood by remaining socially active tend to be happier and healthier (e.g., Kahana, Kelley-Moore, & Kahana, 2012; Park, 2009), partly because community ties can provide new pools of social support. Some scholars also point to the surge of support or increases in social activity that often follows the loss of a close tie (e.g., Ferraro, 1984; Li, 2007; Utz et al., 2002). This work suggests that trajectories of change in social life are more complex, characterized by points of decline that are often followed by subsequent periods of a resurgence in social connectedness.

Finally, we recognize that continuity and adaptation are, to some extent, socially structured and not entirely under the individual’s control. Research shows that socially disadvantaged older adults have a more difficult time replacing lost ties, regardless of why they were lost (e.g., see Cornwell, 2015; Fischer & Beresford, 2015; Goldman and Cornwell, 2018). There are numerous reasons for this, including the higher rates of residential turnover (e.g., due to foreclosures), job loss, incarceration, and morbidity and mortality that exist in disadvantaged neighborhoods. This provides a valuable clue that social network change is partly a reflection of larger social–environmental processes.

Despite the varied theoretical resources for motivating work along these lines, little is known about how different types of social connections change over time in later life. To what extent do the overarching patterns of steady decline, fluctuation, continuity, and even growth characterize the change in the myriad forms of social connectedness that interest contemporary social scientists?

Data and Methods

The NSHAP is a population-based panel study of noninstitutionalized older adults in the United States (O’Muircheartaigh, English, Pedlow, & Kwok, 2014). The goal of the NSHAP is to understand how health and social context intersect to influence older adults’ well-being. At each wave, data collection consists of in-home interviews conducted by the National Opinion Research Center. Following an in-home interview, respondents were also asked to complete a leave-behind questionnaire (LBQ) to be returned by mail.

The original NSHAP cohort (Wave 1) included 3,005 older adults aged 57–85 at baseline (2005–2006), with a weighted response rate of 75.5%. Wave 2 (2010–2011) includes returning respondents as well as their co-resident partners, if applicable. With 2,261 baseline respondents returning, the conditional response rate for Wave 2 is 89%. Wave 3 (2015–2016) includes 1,592 returning respondents who were present at baseline (70.4% of those who were also present at Wave 2), as well as a new cohort of respondents born between 1948 and 1965 and their co-resident partners. The conditional response rate for returning baseline respondents at Wave 3 is 89.2%. This study focuses only on the baseline respondents who participated in Wave 1 and who participated in Waves 2 and 3 as well. Respondents were between the ages of 67 and 95 years at the time of the Wave 3 interview.

Measurement of Social Connectedness

The NSHAP collects information on older adults’ personal (egocentric) social networks and community involvement at multiple waves. Our measures of social connectedness draw on three sets of questions: One uses data from the social network module that was asked at all three waves, the second uses data from a network change module that was asked at Waves 2 and 3, and the third includes a series of questions measuring various forms of community involvement.

Social network connectedness and structure

At each wave, the NSHAP administered the following name generator as part of the in-home interview to introduce the social network module: “From time to time, most people discuss things that are important to them. For example, these may include good things or bad things that happen to you, problems you are having, or important concerns you may have. Looking back over the last 12 months, who are the people with whom you most often discussed things that were important to you?” This name generator is commonly used to elicit individuals’ core social confidants, including their strongest and most intimate social ties, with whom they are most likely to exchange resources and social support.

Respondents could name up to five network members (i.e., “alters”), who composed Roster A. If the respondent had a spouse/partner who was not named as part of Roster A, she/he was included in Roster B. (At waves 1 and 2, respondents were also asked if there was any one additional person with whom they discussed important matters over the course of the prior year. If so, this person was entered in Roster C.) To ensure consistency in the personal network measures across time, we focus only on the alters listed in Roster A at each wave. Following the enumeration of their network members, respondents were asked to classify the nature of their relationship to each alter (e.g., spouse, friend, neighbor), how often they speak with each alter (1 = less than once a year, 8 = every day), and how often each alter speaks with each of the other alters (0 = have never spoken, 8 = every day).

From this information, we construct a series of social network measures. Network size is measured as the number of alters listed in Roster A (i.e., “confidants”). We measure the average frequency at which respondents report speaking with each confidant (from an ordinal scale, from 1 = “less than once a year” to 8 = “every day”). Because this average is such a granular measure, some amount of change between waves is inevitable. Therefore, before assessing patterns of change, we transform this variable into deciles. Social network density reflects how well-connected respondents’ confidants are with one another and is measured as the proportion of ties that exist in a respondents’ network (relative to the number of possible ties that could exist). As we are interested in the composition of older adults’ social networks, we also assess the proportion of confidants who are kin. Although granular, these variables did not need to be transformed.

Network turnover

Not all changes in network personnel will register in comparisons of network size between two time points. Some networks may remain the same size at both time points and yet experience personnel turnover in the interim. Thus, the NSHAP employs a computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) exercise to reveal specific changes in network roster membership between waves. At Wave 2, interviewers collected each respondent’s Wave 2 confidant roster and preliminary information about respondents’ relationships with confidants. The respondent’s Wave 1 roster was preloaded into the CAPI instrument but was not visible to him/her while completing that first step. After the respondent completed the Wave 2 roster, the CAPI was programmed to display confidants who had been named in previous waves (e.g., their first names or initials, as well as their relationship type and gender). The respondent was then asked to verify which of their Wave 2 confidants matched confidants who had been named at Wave 1. The Wave 1 roster line corresponding to a given Wave 2 alter was then recorded. This matching exercise was repeated at Wave 3 as well, at which time respondents indicated which of their Wave 3 confidants corresponded to which of their previous Wave 1 and/or Wave 2 confidants. The data from these roster matching exercises make it possible to measure inter-wave network change using multiple measures that capture the number of confidants who were named at one wave but not at a subsequent wave (confidants “lost”) as well as the number of confidants who were named at one wave but not at an earlier wave (confidants “added”).

Community involvement

We also examine respondents’ involvement in three forms of community life. These include frequency of religious service attendance, volunteer work, and other forms of organized group activities. The measures of volunteer work and organized group involvement were only collected via the LBQ across all waves, and the religious services measure was collected via the LBQ in Wave 3. Thus, there are more missing data for these measures than for the network measures. We attempt to attenuate for potential selection bias associated with the mail-in return of the LBQ by taking noncompletion of this portion of the survey into account in the calculation of weights. The ordinal frequency of involvement scale for each of these three variables is described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptions and Wave-Specific Distributions of Key Measures of Social Connectedness

| Variable Description | Original NSHAP cohort | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005/2006 | 2010/2011 | 2015/2016 | ||

| Confidant network size | Number of people listed in respondent’s core discussion (“confidant”) network (Roster A). Range: 0–5. | 3.50 (1.42) | 3.79a (1.31) | 3.79a (1.38) |

| Average frequency of contact with confidants | Respondents were asked how often they contact each confidant. Eight possible responses range from “less than once a year” to “every day.” We average these responses across confidants. Range: 0–8. | 6.88 (0.84) | 6.72a (0.84) | 6.70a (0.89) |

| Network kin composition | Proportion of confidants who are spouse, (step-) children, or other kin. Range: 0–1. | 0.69 (0.32) | 0.66a (0.32) | 0.65a (0.33) |

| Network density | Proportion of network members in Roster A who know each other. | 0.86 (0.24) | 0.84 (0.24) | 0.82a,b (0.27) |

| Religious services attendance | Frequency of attending religious services, ranging from “never” (=1) to “several times a week” (=6). | 2.49 (1.76) | 2.52 (1.77) | 2.32a,b (1.77) |

| Volunteer work | Frequency of volunteer work in the past year, ranging from “never” (=1) to “several times a week” (=7). | 2.25 (2.10) | 2.23 (2.13) | 2.04a,b (1.88) |

| Organized group involvement | Frequency of attending meetings of organized groups, ranging from “never” (=1) to “several times a week” (=7). | 2.69 (2.12) | 2.76 (2.60) | 2.43a,b (2.27) |

Notes: All estimates are weighted to adjust for differential nonresponse at baseline and probability of attrition between waves. All models are survey adjusted. A Sample is limited to baseline participants who participated in all three waves. NSHAP = the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project.

aSignificantly different from Wave 1 estimate (p < .05).

bSignificantly different from Wave 2 estimate (p < .05).

Analytic Strategy

Our goals are (a) to describe overall levels of change in social connectedness during the 10-year period and (b) to examine how patterns of change during the two inter-wave periods are sequentially related to each other. We use all three waves of the NSHAP data. We begin by comparing the proportion of respondents who experience changes in the social network and community connectedness measures between waves. To examine patterns of change respondents experienced during this period, we then present detailed breakdowns of the sequences of changes they reported from one 5-year study period to the next.

Our analyses focus on respondents who were interviewed at all three waves and who have nonmissing data on each of the network and community involvement variables. To address issues with selection and attrition that arise with this restriction, when calculating estimates we use an inverse probability adjustment that is designed to give greater analytic weight to those respondents included in the analysis who most resemble those respondents who died or otherwise attrited between waves, on the basis of variables that predict attrition. We first use a logistic regression model to predict whether each Wave 1 respondent is included in a given analysis using a number of sociodemographic, health, and life-course indicators. From this model, we derive each respondent’s predicted probability of inclusion in the final analytic sample. The inverse of these probabilities is multiplied by the Wave 1 respondent-level weights provided by the NSHAP, and these weights are applied to all model estimates in conjunction with adjustments for the NSHAP survey design (clustering and stratification). The use of these weights helps to provide estimates that better resemble the estimates that would have been derived had all Wave 1 respondents also participated in the subsequent waves (Morgan & Todd, 2008). In addition to this weighting adjustment, we close the results section by examining whether Wave 1 respondents who did and did not participate through Wave 3 differ in terms of their measures of baseline social connectedness. (We should note that the main findings that we report here do not depend on the use of our adjustments for survey/design effects.)

Findings

Social Network Structure

Descriptive statistics regarding basic attributes as well as the levels of social connectedness of members of the original NSHAP cohort across all three waves are presented in Table 1.

Aggregate change

We first draw attention to several general over-time trends in older adults’ levels of social connectedness across the entire 10-year study period. Overall network size exhibits statistically significant growth between Wave 1 and subsequent waves. The average network included 3.5 confidants in 2005/2006, 3.8 in 2010/2011, and 3.8 again in 2015/2016 (F = 22.74 between Waves 1 and 3; p < .001). The frequency of contact with network members shows a slight but significant decrease between waves (F = 29.68 between Waves 1 and 3; p < .001). The proportion of network members who are kin declines modestly between study periods, from 69.2% to 65.0% (F = 11.83 between Waves 1 and 3; p < .001). Finally, network density shows a slight decline between Waves 1 and 2 that is not significant (F = 2.22, p = .14), but a more significant decline over the 10-year period (F = 16.10, p < .001).

Sequential change patterns

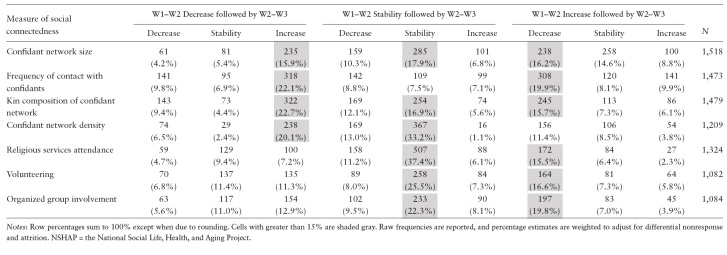

One of our goals is to examine how changes that are observed in different inter-wave periods are related to each other. Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of different patterns of change during the 10-year study period. Each row shows the sequence patterns for sequences of increases, decreases, and stability for different dimensions of social connectedness in the two study periods. For example, the first row shows that 285 respondents (17.9%) reported the same network size (stability) between Waves 1 and 2 as well as between Waves 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Sequential Patterns of Change in Levels of Social Connectedness Among All NSHAP Respondents Who Were Present at Waves 1–3

The most common patterns are indicated with shaded cells. We draw the reader’s attention to two general findings with respect to the social network measures (i.e., network size, frequency of contact, kin composition, and network density). First, a common sequence for these variables involves stable network estimates between Waves 1 and 2 followed by continued stability between Waves 2 and 3. This “stability → stability” pattern is evident for network size, kin composition, and network density. The other two most common patterns for social network measures are either (a) a decrease in the network estimate between Waves 1 and 2 followed by an increase between Waves 2 and 3 (“decrease → increase”) or (b) an increase in the network estimate between Waves 1 and 2 followed by a decrease in Waves 2 and 3 (“increase → decrease”). Together, these three patterns account for 50.0% of cases with respect to the change in confidant network size, 49.5% of contact frequency change, 55.3% of kin composition change, and 64.7% of network density change patterns. Design-adjusted statistical tests show that the patterns of change observed between Waves 1 and 2 for each variable (decrease, stability, or increase) are highly statistically related to the patterns of change observed between Waves 2 and 3 for that variable (for network size: χ2 = 244.44, p < .0001; for frequency of contact: χ2 = 153.97, p < .0001; for kin composition: χ2 = 380.23, p < .0001; for network density: χ2 = 619.17, p < .0001; for all tests, df = 4).

Age differences in sequence patterns

These sequence patterns are evident across age groups. Supplementary Appendix Tables A1 and A2 show the same analysis that is presented in Table 2, but separately for younger NSHAP respondents (those who were in the 50s and 60s at baseline) and older respondents (aged 70s and 80s at baseline). For both age groups, chains of stability are again the most common pattern, followed by the “increase → decrease” patterns and the “decrease → increase” patterns. Nearly all of the 27 most common (shaded) patterns that are observed in the younger age group are also among the most common patterns in the older age group. The main difference is that, in the older age group, there is a slightly greater tendency for increases to be followed by increases (with respect to network size and contact frequency) and a lower tendency for decreases to be followed by decreases (with respect to contact frequency and kin composition).

Social Network Turnover

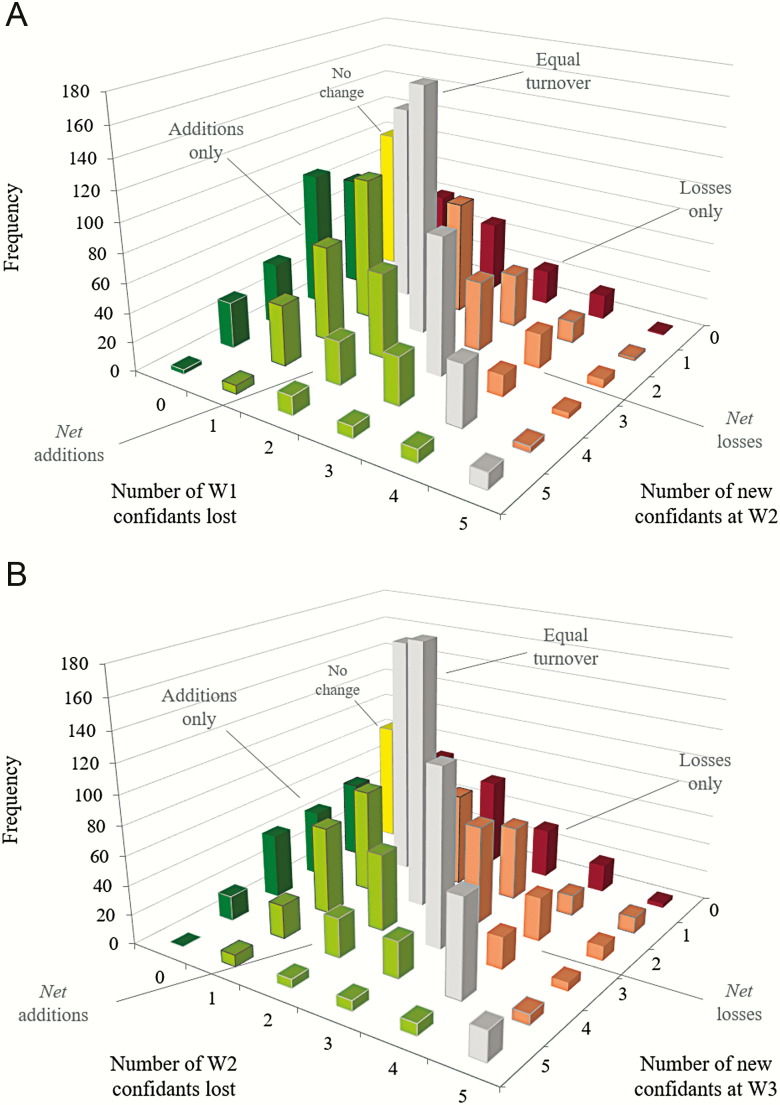

We now focus on the possibility that respondents’ networks could have involved turnover in the specific individuals that comprise their networks without reflecting overall changes in network size. To illustrate, Figure 1 displays different patterns of turnover that are observed in the confidant networks of respondents who completed the roster comparison exercise at all three waves. The left panel shows patterns of turnover between Waves 1 and 2, and the right panel shows patterns of turnover between Waves 2 and 3.

Figure 1.

Comparison of egocentric network turnover patterns between Waves 1 and 2 versus network turnover patterns between Waves 2 and 3 among returning NSHAP respondents. Note: Figures are based on unadjusted, observed frequencies. NSHAP = the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. This analysis includes all respondents for whom valid data on network turnover between both inter-wave periods were available.

It is evident that most respondents’ networks were characterized by a considerable internal change through a given 5-year period. For example, only 6.4% of respondents reported that their confidants at Wave 2 were exactly the same as those named 5 years earlier (the small yellow bar in the back of the left panel). Nonetheless, the overarching pattern is one of homeostasis. Many (35.7%) of these respondents experienced internal changes but nonetheless ended up with the same number or confidants at both waves. Note that 81.9% of the respondents whose networks did not change in size, nonetheless, experienced turnover with respect to their network personnel. This pattern of “equal turnover” is indicated by the tall ridge of gray bars that runs up the middle of the figure.

The turnover patterns for the first 5-year period are similar to those for the second 5-year period. In both panels, “no change” is the least common pattern, and “equal turnover” is the most common pattern. The main difference is that, in the second 5-year period, (net) losses become slightly more common, increasing from 24.8% of the sample to 30.2% of the sample. These results provide some evidence that, during a given 5-year period, older adults tend to maintain networks of similar sizes despite various changes to their network personnel.

Sequential turnover

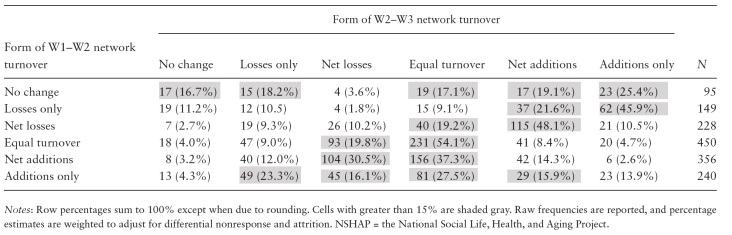

We gain further insight into the sequential nature of these changes by linking the turnover patterns that are observed between the first two waves and those for the second two waves. Table 3 provides a breakdown of connections between patterns of turnover between the two inter-wave periods. For example, row 1 shows that of the 95 people who reported no change in their network personnel between Waves 1 and 2, only 17 again reported no change between Waves 2 and 3. (That leaves only 78 people [5.1%] in the entire sample who reported the same exact confidants all three times.)

Table 3.

Sequential Patterns of Change in Forms of Social Network Turnover Among All NSHAP Respondents Who Were Present at Waves 1–3

Table 3 reveals several general patterns. First, “equal turnover” is the most common pattern between Waves 2 and 3, almost regardless of the pattern that was observed between Waves 1 and 2. The exceptions are from respondents who reported (net) losses between Waves 1 and 2. Among those who experienced (net) losses between Waves 1 and 2, (net) additions compose the most common pattern observed between Waves 2 and 3. For example, of those who only experienced losses (without replacement) in the first period, 67.5% reported (net) additions in the second inter-wave period. On the flip side, among respondents who reported (net) additions between Waves 1 and 2, (net) losses are among the most common patterns between Waves 2 and 3. For example, of respondents who reported only additions (without losses) in the first period, 39.4% reported (net) losses in the second inter-wave period, constituting the majority of people in this subgroup who did not experience equal turnover in the second inter-wave period. The patterns of turnover observed between Waves 1 and 2 (no change, losses only, net losses, equal turnover, net additions, or additions only) are highly statistically related to the patterns of change observed between Waves 2 and 3 (χ2 = 574.79 [df = 25], p < .0001).

Community Involvement

Aggregate change

Descriptive statistics regarding levels of community involvement across all three waves are presented in Table 1. After a slight but nonsignificant increase between Waves 1 and 2, the frequency of religious services attendance declines significantly across the entire study period (F = 13.24, p < .001). Levels of volunteer work remain similar across waves as well, with a slight but significant decline between Waves 1 and 3 (F = 6.08, p < .05). The same is true of organized group involvement (F = 10.96, p < .01).

Sequential change patterns

Patterns of change between subsequent inter-wave periods are presented in the bottom three rows of Table 2. Note that the same patterns that were most common in measures of social network connectedness are also the most common in measures of community involvement. In all three forms of community involvement, the “stability → stability” pattern is the most common. The second-most-common pattern in all three cases is the “increase → decrease” pattern. The “decrease → increase” pattern is the next-most common pattern in the case of organized group involvement (and nearly so in the case of volunteering), although the “decrease → stability” pattern is also common in the case of religious services attendance. As mentioned previously, the “stability → stability,” “increase → decrease,” and “increase → decrease” patterns account for the majority of cases in the sample. They account for 60.1% of cases with respect to the frequency of religious services attendance, 53.4% with respect to the frequency of volunteering, and 55.0% with respect to the frequency of organized group involvement. The patterns of change observed between Waves 1 and 2 for each variable (decrease, stability, or increase) are again highly statistically related to the patterns of change observed between Waves 2 and 3 for that variable (for religious services attendance: χ2 = 298.95, p < .0001; for volunteering: χ2 = 186.19, p < .0001; for group involvement; χ2 = 243.76, p < .0001; for all tests, df = 4).

Sequenced Change Across Different Forms of Connectedness

People might compensate for changes in one form of social connectedness with subsequent changes in another. For the sake of parsimony, we conduct a simple analysis of how changes in average frequency of community involvement (standardized and averaged across all three types) are related to subsequent changes in average frequency of network contact, and vice versa. We focus on these two forms of social connectedness because they address a similar dimension of social contact (i.e., frequency) and are thus measured on similar scales (i.e., time).

Results of this analysis are presented in Supplementary Appendix Figure A1. There is no clear pattern in the sequential changes between these two forms of connectedness. For example, similar numbers of respondents followed decreases in community involvement between Waves 1 and 2 with decreases in network contact between Waves 2 and 3 (13.8%) as with increases in network contact during this period (13.4%; F = 0.04, p = .84). Likewise, similar numbers of respondents followed increases in community involvement between Waves 1 and 2 with decreases (15.7%) as followed increases in community involvement with increases (12.5%; F = 2.96, p = .09). Overall, the relationship between the two sets of changes is not significant (F = 0.46, p = .76).

A similar pattern appears when exploring how changes in the frequency of network contact between Waves 1 and 2 are linked to changes in the frequency of community involvement in the subsequent period. The proportion of people reporting the “increase → decrease” pattern (14.7%) is not much different from the proportion reporting the “increase → increase” pattern (15.6%; F = 2.78, p = .10), and the proportion of people reporting the “decrease → increase” pattern (14.8%) is similar to the proportion reporting the “decrease → decrease” pattern (11.9%; F = 0.25, p = .62). See Supplementary Appendix Figure A1 for specific estimates. Overall, the relationship between these two sets of changes is marginally significant (F = 2.13, p = .08).

Conclusions and Discussion

Life-course theories of social connectedness are implicitly concerned with the processes through which individuals’ social ties change (Alwin, Felmlee, & Kreager, 2018; Atchley, 1989; Charles & Carstensen, 2010; Cumming & Henry, 1961). Although much research has been done to understand how social connectedness is associated with age in general, little light has been shed on how long-term changes in social connectedness unfold in later life. We used recent nationally representative longitudinal data from the NSHAP study to examine profiles of changes that occur in various types of social connectedness among older Americans.

Although most older adults experience considerable turnover within their social networks, they tend to either maintain their original network size or cultivate somewhat larger networks over time.1 Their networks tend to remain largely unchanged in terms of their internal composition and structural features. We see a few trends with respect to older adults’ frequency of contact with their network members, kin composition, or network density. This suggests that even though older adults do experience myriad potentially isolating life-course changes such as retirement and confidant death (e.g., see Umberson et al., 2017), their core networks tend to remain relatively stable. And we find similar trends with respect to religious participation, volunteerism, and involvement with organized groups.

Our analysis shows that older adults’ social connections change sequentially over time, as evidenced by the highly significant statistical tests presented earlier. What does this sequential change look like? Few older adults experience continuous declines in their social connections. Likewise, few of them experience continuous growth. Rather, two overarching patterns emerge (a) a tendency for structures and levels of social connectedness to remain stable; and, relatedly, (b) a tendency for any changes that occur in one time period to be followed by countervailing changes in the subsequent period. These patterns are evident in measures of social network size, composition, and density, social network turnover, and the measures of community involvement.

What do these findings say about central theories of changing social connections in later life? For one, it remains apparent that older adults do not simply disengage from society in some uniform and predictable way. This is not a surprise. Likewise, we find little evidence of increasing selectivity among older adults toward more close-knit and socioemotionally invested personal connections. On the contrary, older adults appear to replace their lost network members with new ones. And, as we have found, oftentimes they replace erstwhile contacts with new acquaintances who are not at all well connected to their network. These patterns are evident across age groups. Likewise, we cannot conclude that aging is generally associated with increased social connectedness.

Rather, what we report here is more consistent with the idea that there is an overwhelming tendency toward stability and rebalancing. Most of the older adults who experienced decreases in a given form of connectedness reported increases in the subsequent time period. This is partly consistent with theories about older adults’ conscious adaptation and compensation in the face of loss and potential social isolation, in the name of continuity (see Atchley, 1989). Moreover, most of the older adults who experienced increases in a given form of connectedness reported decreases in the subsequent time period. We want to underscore that while this form of rebalancing is present, at least implicitly, in continuity theory, it is rarely featured in empirical research.

Although our analysis in this vein is not comprehensive, there is an important caveat in this story of rebalancing. Different forms of social connectedness (e.g., personal network connectedness vs community involvement) do not seem to be interchangeable as sources of “compensation.” Although changes in a given form of social connectedness are typically followed by countervailing changes in that same form of social connectedness, it does not appear that these are paralleled by similar changes in other forms of connectedness. For example, there is little evidence that declines in one’s frequency of network contact are typically followed by subsequent increases in community involvement. This is one reason why we prefer to use the term “rebalancing” as opposed to the term “compensation.” Compensation can imply that different forms of social connectedness are substitutable, which does not appear to be the case. Again, our analysis of this issue is brief, and more research on this is needed.

We should also note that patterns that resemble homeostasis can emerge from processes of regression toward the mean. We have addressed this possibility in a set of supplemental analyses that are presented in Supplementary Appendix B. There, we present evidence that these patterns of stability and rebalancing remain even when potential floor and ceiling effects are taken into account, suggesting that what we document in this paper is not merely regression toward the mean.

Overall, this set of findings is consistent with the idea that a combination of life-course events, individual efforts, and social-environmental factors interact to engender homeostasis in individuals’ social lives over time. Our findings, and those described in the compensation and adaptation literature, are consistent with the broader perspective that social networks are systems that are embedded in the larger surrounding social environment (Parsons, 1951). As such, they are shaped by the same stabilizing (or, in some cases, destabilizing) forces that operate in those larger environments. This system-level framework of homeostasis was present in early social-gerontological theorizing (e.g., see Kutner, 1962), and our findings suggest that this early conceptual framework still has value. Older adults’ social networks appear to maintain their internal structure over time rather than disintegrating. Ironically, Cumming and Henry (1961) buttressed their theory of disengagement with a functionalist argument about homeostasis, stating that older adults’ supposed disengagement is necessary in order to maintain existing role systems via replacement with younger people. The available data instead indicate that a more restorative form of homeostasis operates at the individual level, suggesting a new application of early structuralist theories to analyses of network dynamics.

Limitations and Future Directions

The social−gerontological perspectives that provide our theoretical motivation imply that sequential patterns of social network change in later life are tied up with life-course transitions such as retirement, bereavement, and health decline. A key next step is to understand what role these kinds of processes play in the general pattern of homeostasis that we document here. The fourth wave of data, which is in development, will be useful in this respect.

The “important matters” network name generator captures a core element of older adults’ networks (cf., Bearman & Parigi, 2004). But apart from the community involvement data, the NSHAP provides little information about other types of contacts, such as casual acquaintances, sources of various forms of support, and other types of contacts. We are unable to comment on how these networks shape the actual amount of social interaction and activity older adults experience in everyday life (e.g., see Marcum, 2013). We also have little information about older adults’ use of online social media, portable communication devices like smartphones, or other social networking tools. We are unable to explore how changes in these things relate to changes in these other dimensions of older adults’ social lives. Such data would be indispensable in understanding how aging relates to changes in personal networks more generally (i.e., not just among confidants), and thus would provide insight into how later-life transitions affect weak ties and peripheral contacts.

We do not address some issues that are beyond the scope of this paper. For example, we do not examine non-American populations. Furthermore, we do not address the issue of social context—especially relating to household and neighborhood factors. There is increasing interest in the role that neighborhood-level factors (such as social disorder or poverty rates) play in shaping older adults’ access to social connections (e.g., Sharp, 2018; York Cornwell & Behler, 2015). This research suggests that local contexts play a role in regulating change in individuals’ networks, just as they delineate opportunity structures for community involvement. Understanding the role of neighborhoods is likely critical for understanding the interaction between individual and social–environmental factors that hinder or facilitate homeostasis.

We document these patterns not only because patterns of fluctuation in social connectedness are not yet well understood, but also because they are likely consequential for older adults. Some research has documented, for example, the potential health consequences of changes in social connectedness (e.g., Bookwala, 2016; Cornwell & Laumann, 2015). Future work should consider the potential individual-level consequences of social–environmental stability as well as individuals’ abilities to rebalance following such changes. These dynamics might hold clues about social disparities in health in later life.

Finally, we remain acutely aware that we are dealing with a select sample of people who did not die or drop out of the sample across the 10-year study period. This raises serious questions about the selection. We document this issue in Supplementary Appendix C, where we show that respondents in this sample were disproportionately more socially connected at earlier waves than were those who dropped out. Although we attenuated such effects via propensity score weighting, researchers should, nonetheless, take into account the possibility that people who are more socially connected from the start are better able to achieve homeostasis.

Nonetheless, the NSHAP data provide important insights into the nature of change in older adults’ social lives. This is a portrait of stability and rebalancing. But heterogeneity across different individuals’ trajectories of change in social connectedness deserves serious scholarly attention. There, we may find clues about sources of variation in other important later-life outcomes as well, such as health decline and mortality. Future research on this topic will need to focus not only on collecting new and extended data on different forms of social connectedness over time for different cohorts, but will also need to develop and synthesize theories regarding sources of change in older adults’ social lives.

Funding

The National Social Life, Health and Aging Project is supported by the National Institute on Aging and the National Institutes of Health (R37AG030481, 5RO1AG021487).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank L. Philip Schumm and Erin York Cornwell for providing useful suggestions that improved this paper.

Footnotes

That network growth is to some extent more common than network depletion could be due to panel conditioning. With each successive wave, respondents learn to expect what kinds of questions will be asked and might be better prepared to enumerate names. This possibility deserves further study.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

References

- Alwin, D. F., Felmlee, D. H., & Kreager, D. A. (Eds.). (2018). Social networks and the life course: Integrating the development of human lives and social relational networks. New York: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-71544-5_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley, R. C. (1989). A continuity theory of normal aging. The Gerontologist, 29, 183–190. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.2.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy, P. J., Schafer, M. H., & Sun, H. (2019). Relocation and network turnover in later life: How distance moved and functional health are linked to a changing social convoy. Research on Aging, 41, 54–84. doi: 10.1177/0164027518774805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, P. B., & Baltes, M. M. (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In Baltes P. B. & Baltes M. M. (Eds.), Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences (pp. 1–34). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511665684.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman, P., & Parigi, P. (2004). Cloning headless frogs and other important matters: Conversation topics and network structure. Social Forces, 83, 535–57. doi: 10.1353/sof.2005.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bookwala, J. (2016). Confidant availability (in) stability and emotional well-being in older men and women. The Gerontologist, 57, 1041–1050. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S. L., Nesse, R. M., House, J. S., & Utz, R. L. (2004). Religion and emotional compensation: Results from a prospective study of widowhood. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1165–1174. doi: 10.1177/0146167204263752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles, S. T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 383–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, B. (2009). Good health and the bridging of structural holes. Social Networks, 31, 92–103. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, B. (2015). Social disadvantage and network turnover. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 132–142. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, B., & Laumann, E. O. (2015). The health benefits of network growth: New evidence from a national survey of older adults. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 125, 94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, B., Laumann, E. O., & Schumm, L. P. (2008). The social connectedness of older adults: A national profile. American Sociological Review, 73, 185–203. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, B., Schumm, L. P., Laumann, E. O., Kim, J., & Kim, Y. J. (2014). Assessment of social network change in a national longitudinal survey. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S75–S82. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, C. E., & Dugan, E. (2012). Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 24, 1346–1363. doi: 10.1177/0898264312460275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp, D. A., Windsor, T. D., Butterworth, P., & Anstey, K. J. (2015). Adapting to retirement community life: Changes in social networks and perceived loneliness. Journal of Relationships Research, 6, e9. doi: 10.1017/jrr.2015.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe, R., & Elder, Jr., G. H. (2002). Successful adaptation in the later years: A life course approach to aging. Social Psychology Quarterly, 65, 309–328. doi: 10.2307/3090105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, E., & Henry, W. E. (1961). Growing old: The process of disengagement. New York, NY: Basic Books. doi: 10.1093/sw/7.3.122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, E. A., & Hinterlong, J. E. (2010). Changes in volunteer activity among recently widowed older adults. The Gerontologist, 50, 158–169. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwardt, L., van Tilburg, T., Aartsen, M., Wittek, R., & Steverink, N. (2015). Personal networks and mortality risk in older adults: A twenty-year longitudinal study. PLoS One, 10, e0116731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, K. F. (1984). Widowhood and social participation in later life: Isolation or compensation? Research on Aging, 6, 451–468. doi: 10.1177/0164027584006004001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, C. S., & Beresford, L. (2015). Changes in support networks in late middle age: The extension of gender and educational differences. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 123–131. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, G. N., & Lindstrom, M. (2010). The impact of changes in different aspects of social capital and material conditions on self-rated health over time: A longitudinal cohort study. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 70, 700–710. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, A. W., & Cornwell, B. (2018). Social disadvantage and instability in older adults’ ties to their adult children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 80, 1314–1332. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen, J., & Schulz, R. (1993). Optimization by selection and compensation: Balancing primary and secondary control in life span development. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 16, 287–303. doi: 10.1177/016502549301600210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, K. J., & Mutchler, J. E. (2014). The emergence of a positive gerontology: From disengagement to social involvement. The Gerontologist, 54, 93–100. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana, E., Kelley-Moore, J., & Kahana, B. (2012). Proactive aging: A longitudinal study of stress, resources, agency, and well-being in late life. Aging & Mental Health, 16, 438–451. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2011.644519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, M., Hank, K., & Künemund, H. (2009). The social connectedness of older Europeans: Patterns, dynamics and contexts. Journal of European Social Policy, 19, 327–340. doi: 10.1177/1350506809341514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner, B. (1962). The social nature of aging. The Gerontologist, 2, 5–8. doi: 10.1093/geront/2.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamme, S., Dykstra, P. A., & van Groenou, M. I. B. (1996). Rebuilding the network: New relationships in widowhood. Personal Relationships, 3, 337–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1996.tb00120.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. (2007). Recovering from spousal bereavement in later life: Does volunteer participation play a role? The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62, S257–S266. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.4.s257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, T., & Zhang, Y. (2015). Social network types and the health of older adults: Exploring reciprocal associations. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 130, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcum, C. S. (2013). Age differences in daily social activities. Research on Aging, 35, 612–640. doi: 10.1177/0164027512453468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen, P., Dempster-McClain, D., & Williams, Jr., R. M. (1992). Successful aging: A life-course perspective on women’s multiple roles and health. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 1612–1638. doi: 10.1086/229941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, S. L., & Todd, J. J. (2008). A diagnostic routine for the detection of consequential heterogeneity of causal effects. Sociological Methodology, 38, 231–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9531.2008.00204.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler, J. E., Burr, J. A., & Caro, F. G. (2003). From paid worker to volunteer: Leaving the paid workforce and volunteering in later life. Social Forces, 81(4), 1267–1293. doi: 10.1353/sof.2003.0067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Muircheartaigh, C., English, N., Pedlow, S., & Kwok, P. K. (2014). Sample design, sample augmentation, and estimation for Wave 2 of the NSHAP. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S15–S26. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, N. S. (2009). The relationship of social engagement to psychological well-being of older adults in assisted living facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28, 461–481. doi: 10.1177/0733464808328606 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, T. (1951). The social system. New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, B. L., & Pescosolido, B. A. (2012). Social network dynamics and biographical disruption: The case of “first-timers” with mental illness. American Journal of Sociology, 118, 134–175. doi: 10.1086/666377 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer, K., Moen, P., Wethington, E., & Glasgow, N. (Eds.). (2000). Social integration in the second half of life. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, A. R. (2019). Informal caregiving and network turnover among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, (in press). doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, M. H. (2011). Health and network centrality in a continuing care retirement community. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 795–803. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, M. H. (2013). Structural advantages of good health in old age: Investigating the health-begets-position hypothesis with a full social network. Research on Aging, 35, 348–370. doi: 10.1177/0164027512441612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, E., & Litwin, H. (2018). Social network changes among older Europeans: The role of gender. European Journal of Ageing, 15, 359–367. doi: 10.1007/s10433-017-0454-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman, T. E., Miller-Martinez, D. M., Stein Merkin, S., Lachman, M. E., Tun, P. A., & Karlamangla, A. S. (2011). Histories of social engagement and adult cognition: Midlife in the U.S. study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(Suppl 1), i141–i152. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, G. (2018). Eclipsing community? Neighborhood disadvantage, social mechanisms, and neighborly attitudes and behaviors. City & Community, 17, 615–635. doi: 10.1111/cico.12327 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, B. A., Krause, N., Liang, J., & Bennett, J. (2007). Tracking changes in social relations throughout late life. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(2), S90–S99. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P. A. (2012). Trajectories of social engagement and mortality in late life. Journal of Aging and Health, 24, 547–568. doi: 10.1177/0898264311432310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tilburg, T. (1998). Losing and gaining in old age: changes in personal network size and social support in a four-year longitudinal study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53, S313–S323. doi: 10.1177/0898264311432310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson, D., Olson, J. S., Crosnoe, R., Liu, H., Pudrovska, T., & Donnelly, R. (2017). Death of family members as an overlooked source of racial disadvantage in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114, 915–920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605599114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utz, R. L., Carr, D., Nesse, R., & Wortman, C. B. (2002). The effect of widowhood on older adults’ social participation: An evaluation of activity, disengagement, and continuity theories. The Gerontologist, 42, 522–533. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.4.522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York Cornwell, E., & Behler, R. L. (2015). Urbanism, neighborhood context, and social networks. City & Society (Washington, D.C.), 14, 311–335. doi: 10.1111/cico.12124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.