Abstract

Introduction: Imaging technologies have been developed to assist physicians and dentists in detecting various diseases. Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) is a new technique that shows great applicability to soft tissues. This study aimed to investigate the effect of diode laser intensity modulation on photoacoustic (PA) image quality.

Methods: The prototype of the PAI system in this study utilized a non-ionizing 532 nm continuouswave (CW) diode laser illumination. Samples in this study were oral soft tissues of Sprague–Dawley rats fixed in 10% formalin solution. PA images were taken ex vivo by using the PAI system. The laser exposure for oral soft tissue imaging was set in various duty cycles (16%, 24%, 31%, 39%, and 47%). The samples were embedded in paraffin, and PA images were taken from the paraffinembedded tissue blocks in a similar method by using duty cycles of 40%, 45%, 50%, 55%, 60% respectively to reveal the influence of the laser duty cycle on PA image quality.

Results: The oral soft tissue is clearly shown as a yellow to red area in PA images, whereas the nonbiological material appears as a blue background. The color of the PA image is determined by the PA intensity. Hence, the PA intensity of oral soft tissue was generally higher than that of the nonbiological material around it. The Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Mann–Whitney post-hoc analysis revealed significant differences (P<0.05) in the quality of PA images produced by using a 16%–47% duty cycle of laser intensity modulation for direct imaging of oral soft tissue fixed in 10% formalin solution. The PA image quality of paraffin-embedded tissue was higher than that of direct oral soft tissue images, but no significant differences in PA image quality were found between the groups.

Conclusion: The PAI system built in this study can image oral soft tissue. The sample preparation and the diode laser intensity modulation may influence the PA image quality for oral soft tissue imaging. Nonetheless, the influence of diode laser intensity modulation is not significant for the PA image quality of paraffin-embedded tissue.

Keywords: Photoacoustic, Image quality, Laser, Modulation, Oral soft tissue

Introduction

Radiography and imaging technologies are integral parts that complement clinical examination in the dental and medical treatments of adult and pediatric patients.1,2 The imaging technology in dental and maxillofacial diagnosis is advancing from X-ray radiography that utilizes ionizing radiation into several imaging technologies that utilize non-ionizing radiation, such as ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging.1,3 Recent studies have revealed that the latest biomedical imaging technology known as photoacoustic imaging (PAI) can be applied in dentistry, from ex vivo4 to in vivo studies5 and clinical applications.6

PAI is a new emerging imaging technique based on the photoacoustic (PA) effect. The PA effect is observed when the absorption of electromagnetic (EM) waveforms, such as radiofrequency and optical waves, subsequently generates transient acoustic signals in media. Such absorption leads to local heating in materials through thermoelastic expansion, which can produce (photo-) acoustic waves.7-9

X-ray radiography is more suitable to image hard tissue than soft tissue. Meanwhile, PAI overcomes the limitation of previous biomedical imaging modalities in soft tissue imaging by combining the merits of optical and acoustic imaging, rendering it a promising structural, functional, and molecular imaging modality for a wide range of biomedical applications.7,10,11 Different from X-ray radiography, PAI utilizes non-ionizing EM waves that are commonly generated by lasers or other optical energy sources.12 This imaging technique can image organs, tissues, and cellular structures with good resolution and excellent contrast.7,10,11 PA techniques were initially studied in non-biological fields such as physics and chemistry. Since Theodore Bowen introduced PAI as a biomedical imaging modality in 1981, this technology has been developing quite rapidly.11

Considering that different biological tissues have different absorption coefficients, we can rebuild the distribution of optical energy deposition and obtain images of biological tissue by measuring the acoustic signals with ultrasonic transducers7 or other acoustic detectors such as microphones.13 Biological tissues contain several types of endogenous chromophores, such as hemoglobin, melanin, and lipids. These endogenous chromophores can absorb the EM energy from lasers or other EM sources and then generate laser-induced acoustic or PA waves.11,14 Endogenous chromophores have stronger absorption coefficients than other tissue constituents.11 Thus, they may act as an endogenous contrast agent in PAI.

The PAI system is commonly built by integrating ultrasound transducers as detectors with a laser as an EM source.15 PA signals are generated by using either a pulsed laser or a modulated continuous-wave (CW) laser as an EM source.16 The pulse width modulation (PWM) technique can be applied to produce modulated excitation on CW lasers by regulating the duty cycle and pulse width periodically at a single frequency, thereby obtaining a square wave with fluctuating laser radiation.4,16,17

The pulsed laser is the most widely used in the PAI system because it produces a higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) than the CW laser. However, this laser is large and bulky, lacks practical utility, and is not portable. In addition, it is expensive, requires external cooling systems, and needs re-alignment to be operated by technically experienced personnel. These disadvantages limit its practical use.18 By contrast, the CW diode laser offers an attractive alternative as an excitation source of the PAI system because it is small, inexpensive, compact, and durable.14 Recently, the feasibility of diode laser-based PAI has been explored in vivo for superficial imaging of blood vessels and skin.10,14,19

In this study, we demonstrated a simple PAI system in which an intensity-modulated CW diode laser is used as an EM source. The diode laser was combined with a condenser microphone and a customized X-Y stage in the PAI system to reduce the cost considerably.

PA wave is generated by thermal expansion caused by the absorption of modulated EM waves in the medium. This PA wave has the same frequency with the EM wave frequency being modulated. The amplitude of the PA wave frequency received by the detector is called the PA intensity. Each pixel in the PA image represents the PA intensity. The PA intensity is directly proportional to the fraction of one period in a signal (known as duty cycle) of the modulated laser light.

The PA image quality is generally affected by the number of pixels that represent the image resolution. Besides that, it is also affected by the contrast between the sample and the surrounding medium observed in the same image. Thus, PA image contrast depends on the PA intensity which is derived from the absorption coefficient of the material that is converted to acoustic signals by local thermal expansion. The PA wave is simply generated from a material when the radiation energy exceeds the threshold of absorbed energy. Therefore, in generating the PA intensity, the radiation energy of the modulated laser must pass the threshold of energy absorbed by a material. In PAI, increasing the pulse energy of the laser will enhance the SNR.20 We hypothesize that the duty cycle of diode laser modulation in this study is proportional to the radiation energy that determines the contrast of the PA image and subsequently influences the PA image quality. Furthermore, this study was conducted to investigate the influence of the duty cycle in CW laser modulation using the PWM technique on PA image quality.

Materials and Methods

Photoacoustic Imaging System

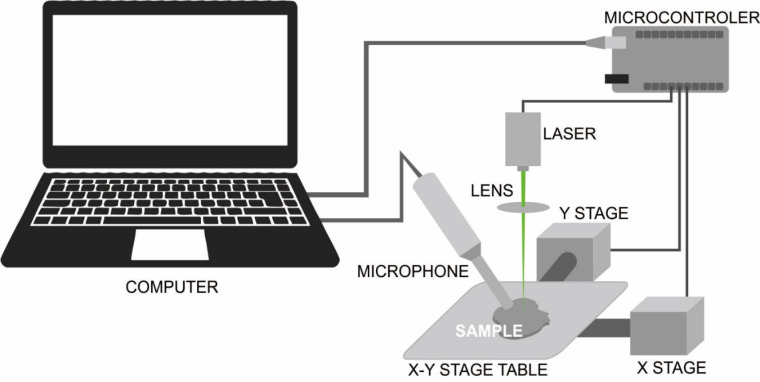

The schematic diagram of the PAI system built in this study is shown in Figure 1. The PAI system configuration for oral soft tissue imaging used three simple main components, namely the modulated excitation CW diode laser as the EM source, condenser microphones as detectors, and the custom-build X-Y stage as mechanical components as described in our previous study.4

Figure 1.

The Schematic Diagram of the PAI System. The system used a 532 nm diode laser with maximum output power of 200 mW as an EM source, a condenser microphone as a detector, and a customized X-Y stage to move the sample during PA imaging.

A diode laser is a major component in the PAI system. A laser beam provides energy in the form of radiation to be absorbed by the tissue or material. The diode laser modulation was controlled via a TTL laser pin connected to a microcontroller using the PWM technique. The PWM technique is commonly used to reduce the average power delivered by an electrical signal by effectively chopping it up into discrete parts. This technique was applied in this study to produce a fluctuating square signal of intensity-modulated CW excitation by adjusting the duty cycle at a single frequency in the audiosonic range. The duty cycle describes the proportion of ‘on’ time to the regular interval or ‘period’ of time. A low duty cycle corresponds to low power because the power is off for most of the time. The duty cycle is expressed in percent, 100% being fully on. When a digital signal is on half of the time and off for the other half of the time, the digital signal has a duty cycle of 50%. Thus, the greater the laser duty cycle, the higher the intensity of laser exposure is.

On the basis of the PA image formation method, the PAI system built in this study applies PA microscopy with a reflection mode of laser-object-detector configuration. The PA image reconstruction in this system applies a direct image reconstruction method based on mechanical scanning using a condenser microphone as an acoustic detector combined with a focused CW diode laser as an EM source. This study did not apply any algorithm for PA image reconstruction. To generate two-dimensional PA images, a scanning process needs to be conducted to obtain a data sequence of acoustic signals. Furthermore, those will be reconstructed from an X-Y direction for 2D images or from an X-Y-Z direction for 3D images. The 2D scanning in this work was performed point-by-point in linear scanning along the surface of the sample object using the custom-build X-Y stage in the PAI system (Figure 1), which moved the sample in the horizontal X-Y plane with a step size of 200 µm between the points that form a repeated S line direction. The scanning method in this PAI system used a Cartesian coordinate system. All systems were controlled by an integrated interface system on the computer.

During the scanning process, the PAI system mapped the PA intensity peak in every scan point. The acoustic signal recorded by the microphone was in the function of time and then it was transformed into frequency function using the Fourier transform to find the intensity peak of the PA signal. Thus, in the present study, PA intensity data were acquired at the same frequency as the laser frequency. Assuming that the optical scattering on the surface and the laser pulse energy variations are considered equal at every scan point on tissue samples, the scan point data were obtained from the intensity of the acoustic signal captured at a frequency range (or wavelength) ideally located at the laser pulsation interval or laser modulation.

The intensity of the laser-generated PA signal from the sample in this study was stored in a 2D array with a resolution of an array dimension determined by the number of X and Y points. The intensity was represented as the contrast in image reconstruction since the PA image mapped the PA intensity from the scanning area (region of interest or ROI) of the sample. PA intensities with high differences produce a high-contrast image and vice versa. PA signals in high intensities were plotted in red color, medium intensities plotted in yellow color, and low intensities plotted in blue color. The color order was used to facilitate the visual distinction of the PA image. PA signal data acquisition, data processing, and PA image reconstruction were performed in a portable computer.

Samples of oral soft tissue were collected from Sprague–Dawley rat tongue and fixed in 10% formalin solution. In the first experiment, PAI was performed directly ex vivo to image the oral soft tissue without any exogenous contrast agents. Following the first experiment, PA imaging was also performed in the samples in the form of paraffin-embedded tissues. Samples of the last experiment were obtained after oral soft tissues underwent tissue processing and blocked in paraffin like those in the routine histopathology procedure. Sample treatments in this study, i.e. tissue fixation and paraffin-embedding, were done to prevent the post-mortem changes and maintain tissue original condition. Nonetheless, the formalin solution was volatile. Hence, we decided to continue the treatment of the sample with paraffin-embedding in order to prevent further changes in samples resulting from the volatilization of formalin during PAI.

The ROI of PAI is marked with white-square for direct soft tissue imaging in the first experiment. For the last experiment, the ROI was the whole sample’s surface in the form of a paraffin block. To ensure that the PAI images produced by the system depict the biological tissue from the non-biological material around it, the ROI includes both the tissue area and the non-biological material area in the sample.

In this study, all samples in each experiment were imaged several times by using five gradual duty cycles of laser modulation to determine the most appropriate duty cycle to be applied in laser modulation using the PWM technique for oral tissue imaging, in addition to an investigation into the influence of laser intensity modulation on the PA image quality. PAI was performed in the same ROI for each sample to ensure that every grade of the duty cycle of laser intensity modulation produces PA images from a similar area on the samples, allowing the quality of PA images from each sample to be assessed and compared. The duty cycles of laser intensity modulation to image the oral soft tissue fixed in 10% formalin solution in the first experiment were 16%, 24%, 31%, 39%, and 47 %, whereas those to image the paraffin-embedded tissues in the last experiment were 40%, 45%, 50%, 55%, and 60% respectively. Therefore, five PA images were produced from each sample in this study, and a total of 60 PA images were collected from six samples in this study, including 30 PA images from the first experiment and 30 PA images of paraffin-embedded tissue collected from the last experiment.

Photoacoustic Image Quality Assessment

The PA images obtained in this study were grouped based on the duty cycle that was used to modulate the laser intensity while producing them, and the PA images in this study were further assessed by two observers based on the PA image quality assessment guide in Table 1. Observers were calibrated before the PA image quality assessment. The Kappa coefficient was calculated to determine inter-examiner agreement regarding the scores of PA image quality.

Table 1. The Assessment Guide of PA Image Quality.

| Score | Criteria |

| 1 | The oral soft tissue image is not visualized in the PA image. The oral soft tissue images cannot be distinguished from the non-biological material surrounding them. Artefacts may obscure the oral soft tissue image. |

| 2 | The oral soft tissue is visualized in the PA image, but it cannot be distinguished clearly from the image of the non-biological material around it. The edge of the oral soft tissue image is not clearly visible. Artifacts may interfere with tissue visualization in the PA image. |

| 3 | The oral soft tissue image is clearly visible in the image and can be distinguished from the image of the non-biological material around it. The edge of oral soft tissue is clearly visible. |

In each experiment, the PA image quality data were separated into five groups based on the duty cycle of the laser intensity modulation used to produce them. The PA image quality between groups was compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Mann–Whitney post-hoc analysis. The significance level was set at 5% (P < 0.05).

Results

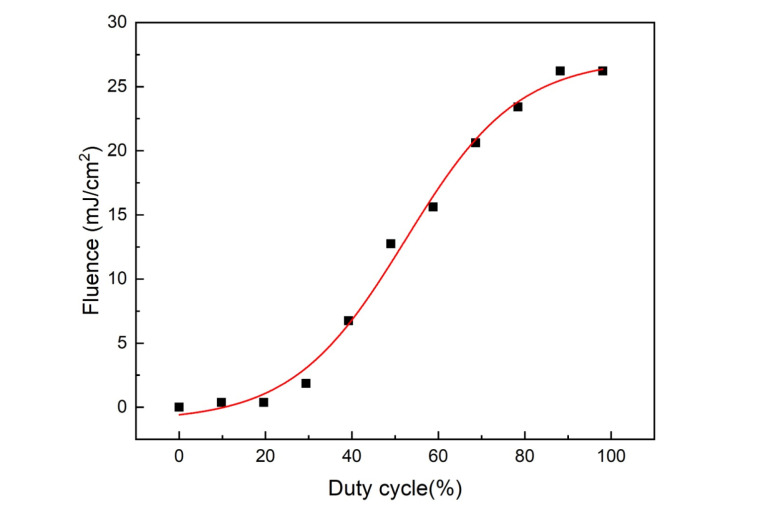

In this study, the modulated CW laser light of a 532-nm wavelength was focused onto a spot of 0.200 µm in diameter on the sample. The optical power delivered to the sample was about 0-140 mW, depending on the duty cycle of laser modulation (Figure 2). For the highest duty cycle applied in this study, the incident light fluence on the tissue was below the ANSI safety limit at a 532-nm wavelength.

Figure 2.

The Surface Fluence of 532 nm CW Diode Laser Illumination Based on the Duty Cycle of Laser Modulation.

The qualities of total PA images in the first and last experiments were assessed by two observers. The PA image quality assessment showed that the kappa value of inter-observer reliability was 0.606 (P < 0.001), which indicates good agreement among the observers.21

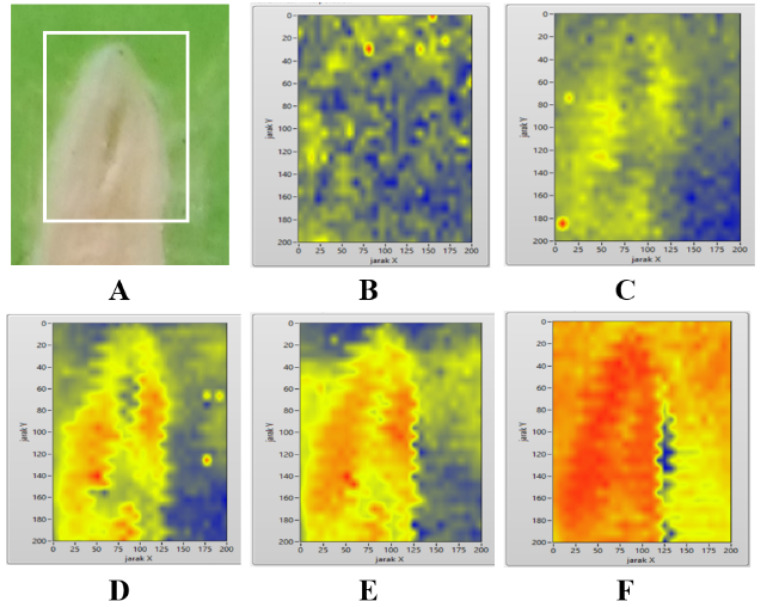

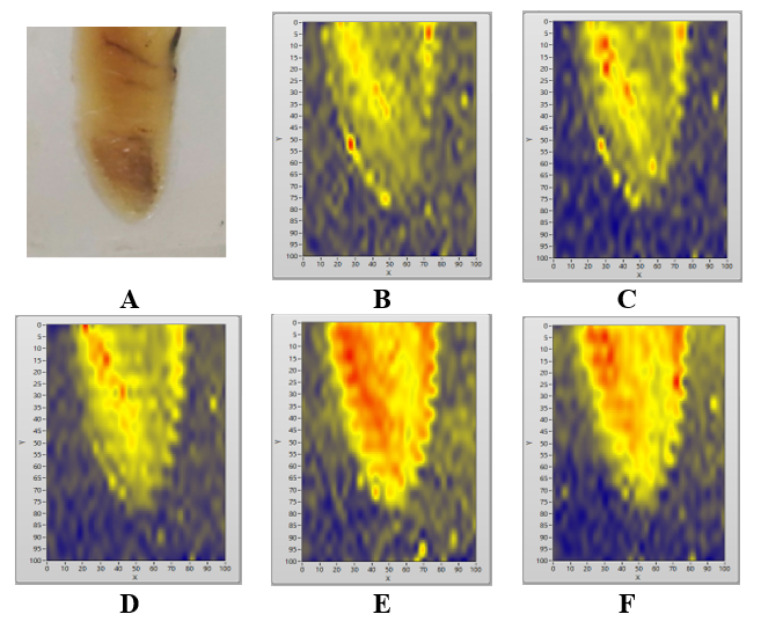

The PA image in the first experiment in this study is shown in Figure 3. As shown in the PAI image in Figure 3D and Figure 3E, the oral soft tissue images present a good match with the photograph of the sample in Figure 3A. The biological tissue in the bottom-left part of the PA images in Figures 3C, 3D, and 3E respectively, are clearly shown as the yellow to red area in the PA image that represents high PA intensities, whereas the non-biological material appears as a blue background in the same PA image that represents low PA intensities.

Figure 3.

Oral Soft Tissue Sample Directly Imaged Without Paraffin-Embedding Treatment (A). The ROI is marked with a white square in the sample (A). PA images of oral soft tissue (B, C, D, E, and F) produced by using various duty cycles of laser intensity modulation: 16% (B), 24% (C), 31% (D), 39% (E), and 47% (F).

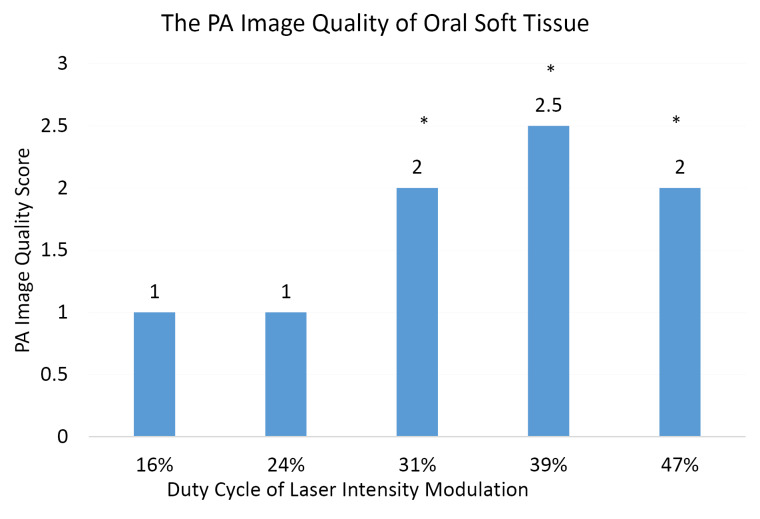

The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Mann–Whitney post-hoc test of the first experiment in Figure 4 showed significant differences among the groups of PA images produced from the direct imaging of oral soft tissue by using laser duty cycles of 16%, 31%, 39%, and 47% respectively, but no significant differences between the PA image group produced by using the laser duty cycle of 16% and the PA image group produced by using the laser duty cycle of 24%. On the basis of the result of the first experiment (Figure 3 and Figure 4), the applicable duty cycles to image oral soft tissue (non-paraffin-embedded tissue) were 31%–39%.

Figure 4.

The PA Image Quality Score of Oral Soft Tissue (Without Paraffin-Embedding Treatment). PA image groups are based on the duty cycle of laser intensity modulation. Scores were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Mann–Whitney test. All values are expressed as the median of six samples. *P < 0.05 versus control (PA images produced by using the laser duty cycle of 16%).

Compared with the previous experiment (Figure 3), the result of the last experiment in Figure 5 indicates that imaging a similar sample in different media (in the form of paraffin-embedded tissue) requires higher duty cycles (e.g., 40%–60%), but the PA imaging was performed using a similar PAI system. The PA image qualities of paraffin-embedded tissue (Figure 6) are higher than those of oral soft tissue fixed in 10% formalin solution in the first experiment (Figure 4), even though the Kruskal–Wallis test in Figure 6 reveals no significant difference in PA image qualities between the groups.

Figure 5.

Sample in the Form of Paraffin-Embedded Tissues (A) and PA Images (B, C, D, E, and F) Produced With Various Duty Cycles of Laser Intensity Modulation: 40% (B), 45% (C), 50% (D), 55% (E), and 60% (F).

Figure 6.

The PA Image Quality Score of Paraffin-Embedded Tissue. The PA image groups are based on the duty cycle of laser intensity modulation. Scores were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test. All values are expressed as the median of six samples. No significant differences between the groups.

Figure 3 shows that various duty cycles applied in laser intensity modulation may influence the quality of PA images. The oral soft tissue is not clearly visualized in the PA images produced by using the lowest (16%) duty cycle of laser intensity modulation (Figure 3B) in the first experiment.

The paraffin-embedded tissues may generate higher PA image quality with no significant difference between the groups as presented in Figure 6. The PA images of paraffin-embedded tissues can be produced by using laser duty cycles of 40%–60%, but the PA image quality in Figure 6 increases when it is produced from higher laser duty cycles.

Furthermore, the highest duty cycle of laser intensity modulation in this study may produce an unwanted red artefact in the PA images (Figure 3F), thereby reducing the quality of PA images. However, an artefact is nearly not found in the PA image of paraffin-embedded tissue in the last experiment (Figure 5). Figure 6 reveals that duty cycles of 50%–60% are the most applicable to modulate the intensity of the CW diode laser in the PAI of paraffin-embedded tissue.

Discussion

Fundamentally, the PA technique measures the conversion of EM energy into acoustic pressure waves. In biomedical PAI, the tissue is irradiated with a pulsed laser, resulting in the generation of an ultrasound wave as a consequence of the optical absorption followed by rapid thermal (or thermoelastic) expansion and subsequent relaxation of tissue.11,22 The thermal expansion needs to be time-variant so that the tissue or material irradiated by the EM wave can generate acoustic waves. This condition can be reached by using either a pulsed laser or a CW laser with intensity modulation as an EM source in the PAI system. The laser intensity modulation for CW wave lasers can be applied at a constant or variable frequency.15

Biomedical PA imaging commonly uses ultrasound transducers as detectors to record the PA signals generated by the sample. The simple and low-cost PAI system built in this study uses an audio-sonic condenser microphone as a detector in the gas-microphone PA technique.13,23 However, the detector must be developed further for in vivo experiments. The modulated CW laser illumination on solid and liquid materials may generate indirect acoustic signals. The acoustic impedance mismatch between the sample and the gas media on the sample surface may weaken the acoustic signal received by the microphone. The acoustic signal in the modulated excitation CW laser technique is not directly generated from the sample, but it may be generated from periodical temperature changes of gas media on the sample boundary between the microphone and the sample.16 Therefore, the increase in temperature due to high duty cycle laser exposure in this study may affect the production of acoustic signals and subsequently increase the PA signal intensity, leading to the generation of artifacts in the PA image (Figure 3F).

The amplitude of the PA signals is affected by EM source radiation and by the optical, mechanical, and thermal properties of the object.18,24 Figures 3 and 5 show that the PA images produced by the PAI system in this study demonstrate that biological tissue can be distinguished from non-biological material. The oral soft tissue shows a higher PA image intensity than the non-biological material around it. Bright color (yellow and red) represents higher PA-signal intensity than the dark (blue) ones. The oral soft tissue is observed as an object surrounded by green media (Figure 3A) or clear paraffin media (Figure 5A) in the photographs of the sample, and it appears as a yellow area (Figures 3C, 5B, 5C, 5D) or yellow and red area (Figures 3D, 3E, 3F, 5E, and 5D) in the PA images. Meanwhile, the surrounding non-biological material produces a blue area. Hence, the biological tissues have higher PA intensity than the non-biological material.

The PAI technique applies the principle of light conversion into the acoustic wave. Thus, the PA image is reconstructed through an imaging process from optically induced acoustic (or ultrasound) signals generated from the sample. Every single point in the PAI image in this study represents the PA signal intensity detected from the same point in the ROI. Higher PA intensity shows a brighter color in the PA image. The color difference between oral soft tissues and the non-biological material around them shows that biological tissue has different mechanical, optical, and thermal properties compared with non-biological materials. The acoustic impedance is likewise influenced by the density of the medium.25,26 Thus, oral soft tissue has different densities and optical properties compared with paraffin. The discrepancy in PA intensity emerged from the different properties of biological tissue and non-biological material in the sample subsequently form image contrast in PA images, which can be viewed in Figures 3 and 5. Furthermore, the contrast of PA images is based on optical absorption.18,27 Thus, adjusting the laser wavelength with the peak absorption of endogenous chromophores in the targeted tissue may improve the PA image contrast. Further studies may consider this aspect to enhance PA image quality.

The results of this study reveal that CW laser modulation may influence PA image quality. Therefore, laser modulation must be applied in the optimum duty cycle to obtain the best PA image quality. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, a significant difference (P < 0.05) exists in the PA image quality produced by using duty cycles of 16%–47%. The low intensity (duty cycles 16%–24%) of focusable diode laser illumination in this study was not adequate to generate PA images of the sample. By contrast, a very high intensity of laser illumination may produce unwanted bio-effects, especially when the laser is focused onto a small spot.28

The magnitude of the PAI signal is proportional to local fluence and the optical absorption coefficient of the illuminated tissue at the wavelength of the light source.29 Transient acoustic waves are produced due to thermoelastic expansion triggered by optical absorption and heating of endogenous chromophores in the tissue. However, due to the low energy conversion efficiency on this process, acoustic attenuation, and scattering in heterogeneous biological tissues, the received acoustic signal is usually very weak and severely distorted, limiting the contrast and resolution in PAI. Increasing the pulse energy of the laser will enhance the SNR in PAI.20 The results of this study in Figures 3 and 5 demonstrated that increasing the laser energy using the higher duty cycle of laser modulation may increase PA image contrast and subsequently increase the PA image quality as well.

Figure 6 reveals that the intensity modulation of the CW laser in 50%–60% duty cycles in this study produces satisfying PA image quality from the samples in the form of paraffin-embedded tissue. As shown in Figures 4 and 6, PA image quality is not only influenced by laser intensity modulation but also by sample preparation. Different sample treatments in this study may influence PA image quality. The PA images of paraffin-embedded tissue (Figure 6) presented different qualities compared with the PA images of oral soft tissue fixed in 10% formalin solution (Figure 4). Tissue fixation using 10% formalin solution has been a routine procedure in histological processing to prevent tissue from post-mortem changes. This procedure has generally continued with tissue inclusion in paraffin,30 known as paraffin-embedding procedure to produce a paraffin-embedded tissue block, as it is used as the sample in the last experiment in this study. Previous studies of PAI using a 532-nm pulsed laser29,31 show the feasibility of the PAI system to image several biological tissues, such as rabbit ears in vivo31 and pig eyes ex vivo.29 However, the sample in previous studies29 did not undergo tissue fixation nor paraffin-embedding so that there was possibly post-mortem changes, subsequently increasing optical surface absorption and influencing the PA image. Despite preventing post-mortem changes, paraffin-embedding procedure possibly influences the tissue optical properties. Comparing Figures 3 and 5, this procedure may influence the optimum duty cycle of laser modulation to produce PA images from them, in spite of increasing the PA image quality in our study.

The superficial tissue dosage in laser irradiation is expressed as fluence or energy density measured in joules per square centimeter (J/cm2). Multiplying the output power of the laser in milliwatts by the time of exposure in seconds equals the produced energy. The fluence is in an inverse relationship with the laser spot size. The broader size of the irradiated area, the lower the fluence produced by the laser beam.32 Thus, for the same laser power, the irradiation of the focusable laser produces higher fluence than a wide laser beam. For human safety, the pulse energy of the laser is limited by the ANSI permitted surface fluence of 20 mJ/cm2 at 532 nm.20,33 Based on the result in Figure 2, the surface fluence of laser irradiation in this study is below the ANSI safety limit. Previous studies demonstrated the feasibility of achieving PAI imaging by using a pulsed laser at a 532 nm wavelength,29,31 with the incident light fluence on the tissue being about 15 mJ/cm2 below the ANSI safety limit at a 532-nm wavelength.31 Although this work utilized a CW laser at the same wavelength, our data in Figure 2 was in agreement with previous studies.29,31 For the highest duty cycle applied in CW laser intensity modulation in this study, i.e. 60%, the surface fluence (Figure 2) did not exceed the ANSI safety limit. This finding is in agreement with previous studies29,31 though CW lasers are considered to be less efficient in generating PA signals.33 Despite producing lower fluence and greater SNR, the pulse PA technique usually utilizes more complicated signal acquisition systems that employ high-cost detectors. The PAI system in this study uses a focused CW laser to adjust the image reconstruction technique. The study may be further developed using CW lasers with a broader spot size or using pulsed lasers combined with ultrasonic transducer technology to obtain high-resolution and better PA image quality.

Most imaging techniques in the dental and medical examination have utilized X-ray radiography, which may induce adverse biological changes related to the oxidative reaction after ionizing radiation exposure in living tissues.34,35 Instead of using ionizing radiation in X-ray radiography, PAI utilizes non-ionizing laser irradiation as an EM source.15

However, we found that studies in PA image quality are still limited. The PA image quality in this study was assessed quantifiably using the guidelines (Table 1) that were devised following routine dental radiograph quality assessments.36 The PA image quality in previous studies29,37-39 was evaluated based on visual observations. We have not found any references regarding quantitative PA image quality assessment. Previous works have utilized image processing, instrumentation engineering, and reconstruction algorithms37,40,41 to improve PA image quality and eliminate specific artifacts in PAI. Furthermore, adjustment of optical beams and ultrasonic detectors may reduce the reflection of light beams on the sample surface while increasing the depth of light penetration and increasing the SNR as well as enhancing the PA image quality.38 Achieving sufficient SNR in deep tissue imaging is still challenging because of the low acoustic pressure generated by thermal elastic expansion. Using high power of the pulse laser in PAI may increase acoustic pressure and SNR, but this method cannot be used in practice because of the limitation in radiative exposure defined by ANSI radiative safety guidelines.37

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the feasibility of a simple PAI system based on the diode CW laser that applies the intensity modulation at a single frequency to image oral soft tissue. The influence of CW laser intensity modulation on the PA image quality has been investigated. The duty cycle of laser intensity modulation considerably affects the PA image quality of oral soft tissue. The PA image is also affected by sample treatment, considering that the PA images of paraffin-embedded tissue in this study show better quality than direct images of oral soft tissue without paraffin-embedding treatment. Nevertheless, efforts must still be invested to develop the hardware and software components of the PAI system and imaging method in further research.

Ethical Considerations

The research protocol was approved by the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada – Dr. Sardjito General Hospital, Yogyakarta, Indonesia (Ref: KE/FK/0285/EC/2017).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no potential conflict of interests regarding the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Scholarship for Graduate Program from The Indonesian Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education and partially supported by a research fund from The Faculty of Dentistry Universitas Gadjah Mada, Indonesia. The authors thank Eddy Kurniawan and Gong Matua for their technical assistance during the study.

Please cite this article as follows: Widyaningrum R, Mitrayana, Sola Gracea R, Agustina D, Mudjosemedi M, Miyosi Silalahi H. The influence of diode laser intensity modulation on photoacoustic image quality for oral soft tissue imaging. J Lasers Med Sci. 2020;11(suppl 1):S92-S100. doi:10.34172/jlms.2020.S15.

References

- 1.Widyaningrum R, Faisal A, Mitrayana M, Mudjosemedi M, Agustina D. Imejing diagnostik kanker oral: prinsip interpretasi pada radiograf dental, CT, CBCT, MRI, dan USG. Maj Kedokt Gigi Indones. 2018;4(1):1–14. doi: 10.22146/majkedgiind.22050. [Indonesian] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suryani IR, Villegas NS, Shujaat S, De Grauwe A, Azhari A, Sitam S. et al. Image quality assessment of pre-processed and post-processed digital panoramic radiographs in paediatric patients with mixed dentition. Imaging Sci Dent. 2018;48(4):261–268. doi: 10.5624/isd.2018.48.4.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez MGS, Bagan JV, Jimenez Y, Margaix M, Marzal C. Utility of imaging techniques in the diagnosis of oral cancer. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43(9):1880–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Widyaningrum R, Agustina D, Mudjosemedi M, Mitrayana Mitrayana. Photoacoustic for oral soft tissue imaging based on intensity modulated continuous-wave diode laser. Int J Adv Sci Eng Inf Technol. 2018;8(2):622–627. doi: 10.18517/ijaseit.8.2.2383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin CY, Chen F, Hariri A, Chen CJ, Wilder-Smith P, Takesh T. et al. Photoacoustic imaging for noninvasive periodontal probing depth measurements. J Dent Res. 2018;97(1):23–30. doi: 10.1177/0022034517729820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore C, Bai Y, Hariri A, Sanchez JB, Lin CY, Koka S. et al. Photoacoustic imaging for monitoring periodontal health: A first human study. Photoacoustics. 2018;12:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Hong H, Cai W. Photoacoustic imaging. Cold Spring HarbProtoc. 2011;2011(9):1015–25. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top065508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallidi S, Luke GP, Emelianov S. Photoacoustic imaging in cancer detection, diagnosis, and treatment guidance. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29(5):213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valluru KS, Wilson KE, Willmann JK. Photoacoustic imaging in oncology: Translational preclinical and early clinical experience. Radiology. 2016;280(2):332–49. doi: 10.1148/radiol.16151414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hariri A, Fatima A, Mohammadian N, Bely N, Nasiriavanaki M. Towards low cost photoacoustic Microscopy system for evaluation of skin health. Imaging Spectrometry XXI. 2016;9976:1–7. doi: 10.1117/12.2238423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehrmohammadi M, Yoon SJ, Yeager D, Emelianov SY. Photoacoustic imaging for cancer detection and staging. Curr Mol Imaging. 2013;2(1):89–105. doi: 10.2174/2211555211302010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen TJ, Beard PC. High power visible light emitting diodes as pulsed excitation sources for biomedical photoacoustics. Biomed Opt Express. 2016;7(4):1260–1270. doi: 10.1364/BOE.7.001260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoshimiya T. Nondestructive evaluation of surface defects under dry/wet environment by the use of photoacoustic and photothermal electrochemical imaging. NDT E Int. 1999;32:133–137. doi: 10.1016/S0963-8695(98)00063-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maslov K, Wang LV. Photoacoustic imaging of biological tissue with intensity-modulated continuous-wave laser. J Biomed Opt. 2008;13(2):024006. doi: 10.1117/1.2904965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia J, Yao J, Wang LV. Photoacoustic tomography: Principles and advances. Electromagn Waves (Camb) 2014;147:1–22. doi: 10.2528/pier14032303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bageshwar D V, Pawar AS, Khanvilkar VV, Kadam VJ. Photoacoustic spectroscopy and its applications – A tutorial review. Eurasian J Anal Chem. 2010;5(2):187–203. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soroushian B, Yang X. Measuring non-radiative relaxation time of fluorophores with biomedical applications byintensity-modulated laser-induced photoacoustic effect. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2(10):2749–2760. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.002749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beard P. Biomedical photoacoustic imaging. Interface Focus. 2011;1(4):602–631. doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2011.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolkman RGM, Steenbergen W, van Leeuwen TG. In vivo photoacoustic imaging of blood vessels with a pulsed laser diode. Lasers Med Sci. 2006;21(3):134–139. doi: 10.1007/s10103-006-0384-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gao F. Multi-Wave electromagnetic-acoustic sensing and imaging. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2017. 10.1007/978-981-10-3716-0 [DOI]

- 21. Petrie A, Sabin C. Medical Statistics at a Glance. 4td ed. Chichester, UK: Willey-Blackwell; 2020.

- 22.Kim J, Lee D, Jung U, Kim C. Photoacoustic imaging platforms for multimodal imaging. Ultrasonography. 2015;34(2):88–97. doi: 10.14366/usg.14062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elia A, Lugarà PM, Di Franco C, Spagnolo V. Photoacoustic techniques for trace gas sensing based on semiconductor laser sources. Sensors (Basel) 2009;9(12):9616–9628. doi: 10.3390/s91209616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu W, Yao J. Photoacoustic microscopy: principles and biomedical applications. Biomed Eng Lett. 2018;8(2):203–213. doi: 10.1007/s13534-018-0067-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ku G, Wang X, Xie X, Stoica G, Wang LV. Imaging of tumor angiogenesis in rat brains in vivo by photoacoustic tomography. Appl Opt. 2005;44(5):770–775. doi: 10.1364/ao.44.000770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lao Y, Xing D, Yang S, Xiang L. Noninvasive photoacoustic imaging of the developing vasculature during early tumor growth. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53(15):4203–4212. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/15/013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dogra VS, Chinni BK, Valluru KS, Moalem J, Giampoli EJ, Evans K. et al. Preliminary results of ex vivo multispectral photoacoustic imaging in the management of thyroid cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(6):W552–558. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strohm EM, Berndl ESL, Kolios MC. High frequency label-free photoacoustic microscopy of single cells. Photoacoustics. 2013;1(3-4):49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverman RH, Kong F, Chen YC, Lloyd HO, Kim HH, Cannata JM. et al. High-resolution photoacoustic imaging of ocular tissues. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36(5):733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cadar ME. Histological Fixation with Formalin under Microwave Irradiation. Bull Univ Agric Sci Vet Med Cluj Napoca. 2012;69(1-2):48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Fowlkes JB, Cannata JM, Hu C, Carson PL. Photoacoustic imaging with a commercial ultrasound system and a custom probe. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2011;37(3):484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Coluzzi DJ, Convissar RA. Laser Fundamentals. In: Convissar RA, editor. Principles and practice oflaser dentistry. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby Elsevier; 2011:12-26.

- 33.Yao J, Wang LV. Sensitivity of photoacoustic microscopy. Photoacoustics. 2014;2(2):87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shantiningsih RR, Diba SF, Andini AD. β-carotene gingival mucoadhesive patch to prevent panoramic radiography exposure’s effect on GCF. In: Nuringtyas TR, Hidayati L, Rafieiy M, editors. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Bioinformatics, Biotechnology, and Biomedical Engineering (BIOMIC 2018); 2018 Oct 19- 20; Yogyakarta, Indonesia. New York: AIP conference proceedings; 2019. p. 0200241-0200244. 10.1063/1.5098429 [DOI]

- 35.Yanuaryska RD. Comet assay assessment of DNA damage in buccal nucosa cells exposed to X-rays via panoramic radiography. J Dent Indones. 2018;25(1):53–57. doi: 10.14693/jdi.v25i1.1124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Whaites E, Drage N. Essentials of Dental Radiography and Radiology. 5th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2013.

- 37. Kim M, Kang J, Chang JH, Song TK, Yoo Y. Image quality improvement based on inter-frame motion compensation for photoacoustic imaging: a preliminary study. Proceedings of the 2013 Joint UFFC, EFTF and PFM Symposium; 2013 July 21- 25; Prague, Czech Republic. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE; 2013. p. 1528-1531. 10.1109/ULTSYM.2013.0388 [DOI]

- 38.Sangha GS, Hale NJ, Goergen CJ. Adjustable photoacoustic tomography probe improves light delivery and image quality. Photoacoustics. 2018;12:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Maslov K, Zhang Y, Hu S, Yang L, Xia Y. et al. Fiber-laser-based photoacoustic microscopy and melanoma cell detection. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16(1):011014. doi: 10.1117/1.3525643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhang C. Total variation based gradient descent algorithm for sparse-view photoacoustic image reconstruction. Ultrasonics. 2012;52(8):1046–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Omidi P, Zafar M, Mozaffarzadeh M, Hariri A, Haung X, Orooji M. et al. A novel dictionary-based image reconstruction for photoacoustic computed tomography. Appl Sci (Basel) 2018;8(9):1570. doi: 10.3390/app8091570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]